Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

East German jokes

View on Wikipedia| Type of joke | Historical joke |

|---|---|

| Target of joke | East Germans |

| Languages |

East German jokes, jibes popular in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR, also known as East Germany), reflected the concerns of East German citizens and residents between 1949 and 1990. Jokes frequently targeted political figures, such as Socialist Party General Secretary Erich Honecker or State Security Minister Erich Mielke, who headed the Stasi secret police.[1] Elements of daily life, such as economic scarcity, relations between the GDR and the Soviet Union, or Cold War rival, the United States, were also common.[2] There were also ethnic jokes, highlighting differences of language or culture between Saxony and Central Germany.

Political jokes as a tool of protest

[edit]Hans Jörg Schmidt sees the political joke in the GDR as a tool to voice discontent and protest. East German jokes thus mostly address political, economic, and social issues, criticise important politicians such as Ulbricht or Honecker, as well as political institutions or decisions. For this reason, Schmidt sees them as an indicator for popular opinion or as a "political barometer" that signals the opinion trends among the population.[3] Political jokes continued the German tradition of the whisper joke.

Legal consequences and Stasi surveillance

[edit]According to researcher Bodo Müller, no one was ever officially convicted due to a joke; rather, the jokes were dubbed propaganda that threatened the state or generally agitated against it. Jokes of this nature were seen as a violation of Paragraph 19, as "State-endangering propaganda and hate speech". The jokes were taken very seriously, with friends and neighbours being interrogated as part of any prosecution. As East German trials were mostly open to the public, the jokes in question were thus never actually read out loud. Of the 100 people in Müller's research, 64 were convicted for having told one or more jokes, with sentences typically varying between one and three years in prison; at the harshest, the sentences could be as long as 4 years.[4]

Most of the sentences were handed down in the 1950s before the Berlin Wall was built. Though the Stasi continued to arrest joke-tellers, sentences against them declined sharply in the following decades; the last verdict of this nature was passed in 1972, against three engineers who had exchanged jokes during a breakfast break. Nevertheless, the Stasi continued to keep tabs on the telling of jokes: throughout the 1980s, monthly reports of popular sentiment delivered by the Stasi to SED district councils revealed a rising frequency of political jokes recounted in workplaces, unions, as well as party rallies, showcasing how the citizenry in the GDR's final years felt increasingly emboldened at every level to speak freely against the state.[5]

Operation DDR-Witz (GDR Joke)

[edit]During the cold war, the GDR was a central focus of the West German Federal Intelligence Service (BND). In the mid-1970s, an employee at the agency's local headquarters in Pullach proposed that its agents and employees collect political jokes "over there" as part of their intelligence gathering; evaluating East German popular sentiment directly was seen as difficult, as people were hesitant to speak openly for fear of being overheard by the Stasi. According to former BND president Hans Georg-Wieck, "political humor in totalitarian systems sometimes reveals grievances (...) more drastically and directly than sophisticated analysis is capable of."[6]

The BND would do just that; dubbing their efforts Operation DDR-Witz (GDR Joke), BND agents were instructed to collect and evaluate political jokes from the GDR. The jokes were collected through a variety of means: in the West, BND surveyors would collect jokes from recently arrived East German refugees, and West German citizens who received visitors from the GDR or visited their East German relatives were asked to supply jokes as well. The wiretapping of phone calls from the GDR were also used to collect jokes. Female BND agents in the East played the part of "train interrogators", collecting jokes on public transport from seemingly benign conversations with fellow passengers. The operation was highly effective and produced thousands of jokes over the course of 14 years, 657 of which were sent as part of regular reports to the Federal Chancellery. Additionally, the operation revealed just how widespread the jokes had become: through wiretaps, it was discovered that political jokes had ended up circulating among the ranks of the SED. The fall of the Berlin Wall did not disrupt the operation; the final report, containing over 30 jokes and several pages of protest slogans, was sent to the Chancellery on 11 November 1990, 39 days after Germany reunified. The BND's surveillance of East Germany, along with Operation DDR-Witz, was subsequently discontinued.[6]

Examples

[edit]Country and politics

[edit]

- Which three great nations in the world begin with "U"? — USA, USSR, and oUr GDR. (German: Was sind die drei großen Nationen der Welt, beginnend mit "U"? USA, UdSSR, und unsere DDR. This alludes to how official discourse often used the phrase "our GDR", and also often exaggerated the GDR's world status.)

- The United States, the Soviet Union and the GDR want to raise the Titanic. The United States wants the jewels presumed to be in the safe, the Soviets are after the state-of-the-art technology, and the GDR – the GDR wants the band that played as it went down.[7]

- Why are other socialist states called "brothers" instead of "friends"? – You can choose your friends but not your brothers.[8]

- Why is toilet paper so rough in the GDR? In order to make every last asshole red.

- Results for international tonsillectomy competition: USA three minutes, France two minutes, GDR five hours. Explanation: in the GDR one can't open one's mouth, so the doctor had to go in the other way.

- Eberhard Cohrs had a famous joke "Do you know the difference between capitalism and socialism? Capitalism makes social mistakes ..." – and the audience usually figured out the punchline themselves.[9]

Stasi

[edit]- How can you tell that the Stasi has bugged your apartment? – There's a new cabinet in it and a trailer with a generator in the street. (This is an allusion to the primitive state of East German microelectronics.)

- Honecker and Mielke are discussing their hobbies. Honecker: "I collect (German sammeln) all the jokes about me." Mielke: "Well we have almost the same hobby. I collect (German einsammeln, used figuratively like to garner) all those who tell jokes about you." (Compare with a similar Russian political joke.)

- Why do Stasi officers make such good taxi drivers? – You get in the car and they already know your name and where you live.

Honecker

[edit]

- Early in the morning, Honecker arrives at his office and opens his window. He greets the Sun, saying: "Good morning, dear Sun!" – "Good morning, dear Erich!" Honecker works, and then at noon he heads to the window and says: "Good day, dear Sun!" – "Good day, dear Erich!" In the evening, Erich calls it a day, and heads once more to the window, and says: "Good evening, dear Sun!" Hearing nothing, Honecker says again: "Good evening, dear Sun! What's the matter?" The sun retorts: "Kiss my arse. I'm in the West now!" (from the 2006 Oscar-winning movie The Lives of Others) A similar Soviet joke exists about Leonid Brezhnev.[10]

- What do you do when you get Honecker on the phone? Hang up and try again. (This is a pun with the German words aufhängen und neuwählen, meaning both "hang up the phone and dial again" and "hang him and vote again".)

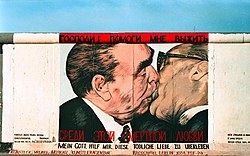

- Leonid Brezhnev is asked what his opinion of Honecker is: "Well, politically – I don't have much esteem for him. But – he definitely knows how to kiss!"

- A man got a care package and got arrested by a Stasi officer. They asked: "who gave you the package?" "My father!" "Where does your father live?" "Berlin" "East or West?" "East" "Who is his boss?" Honecker walks in and arrests the Stasi officer for interrogating him and Brezhnev's child.

Economy

[edit]- When an East German retiree returns from his first trip to West Germany, his children ask him what it was like. He replies: 'Well, it's basically the same as here: you can get anything for West German marks.'

- What are the four deadly enemies of socialism? Spring, summer, autumn, winter.

- How can you use a banana as a compass? – Place a banana on the Berlin Wall. The end that gets bitten points East.

Trabant

[edit]

- What's the best feature of a Trabant? – There's a heater at the back to keep your hands warm when you're pushing it.

- A man driving a Trabant suddenly breaks his windshield wiper. Pulling into a service station, he hails a mechanic. 'Wipers for a Trabi?' he asks. The mechanic thinks about it for a few seconds and replies, 'Yes, sounds like a fair trade.' (Allusion to the shortage of spare parts for cars.)

- A new Trabi has been launched with two exhaust pipes – so you can use it as a wheelbarrow.[11]

- How do you double the value of a Trabant? – Fill it with gas.[12]

- German engineers from the Trabant factory toured an auto assembly line in Japan. At the end of the line they witnessed a Japanese worker put a live cat inside the car and shut the doors. Puzzled, the German engineers asked their tour guide why. The guide replied, "When we come back the next morning, if the cat is dead we know the car was built airtight and thus has passed inspection." The German engineers nod and take notes. When they get back to Germany they put a cat in a Trabant and roll up the windows. When they get back the next morning the cat is gone.

- The back page of the Trabant manual contains the local bus schedule.

- Four men were seen carrying a Trabant. Somebody asks them why? Was it broken? They reply: "No, nothing wrong with it, we’re just in a hurry."

- How do you catch a Trabi? – Place a piece of chewing gum on the road. (Allusion to weak engine.)

Saxons

[edit]- The doorbell rings. The woman of the house goes to the door and quickly returns, looking rather startled: "Dieter! There's a man outside who just asks, Tatü tata?" (Tatü tata is onomatopoeia for the sound of a police car siren). Dieter goes to the door and comes back laughing. "It's my colleague from Saxony, asking s do Dieto da?" (standard German Ist der Dieter da?, i.e. "Is Dieter there?", in Upper Saxon dialect)

- A Saxon sits at a table in a cafe. Another man takes a seat and kicks him in the shin. He glances up briefly but says nothing. The man kicks him again. Now the Saxon says: 'If you do this for a third time, I will switch to another table.' (Allusion to the Saxon's mentality.)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ben Lewis, Hammer and Tickle: A Cultural History of Communism, London: Pegasus, 2010

- ^ Ben Lewis, "Hammer & tickle Archived 2019-04-25 at the Wayback Machine," Prospect Magazine, May 2006

- ^ Schmidt, Hans Jörg. "Ulbricht klopft an die Himmelspforte...: Der politische Witz in der DDR als historisches Kondensat". Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte. 17 (2): 443–446.

- ^ Bodo Mueller (2016). Lachen gegen die Ohnmacht: DDR-Witze im Visier der Stasi

- ^ Locke, Stefan. ""Nie hieß es: War doch nur ein Witz"". Frankfurter Allgemeine. FAZ. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Kein Witz! DDR-Witze als Ziele des BND". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. MDR. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Funder, Anna (2015). Stasiland. Text Publishing. p. 237. ISBN 978-1877008917.

- ^ Hoyer, Katja (2023). Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949–1990. Penguin Random House. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-141-99934-0.

- ^ "Unser kleiner Eberhard – die Tragik eines Komikers"

- ^ von Geldern, James. "Soviet Anecdotes". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. Michigan State University. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ Stoldt, Hans-Ulrich. "East German Jokes Collected by West German Spies". Spiegel Online. Spiegel. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ James, Kyle (19 May 2007). "Go, Trabi, Go! East Germany's Darling Car Turns 50". DW. DW. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Ben Lewis, Hammer and Tickle: A Cultural History of Communism, London: Pegasus, 2010

- Ben Lewis, "Hammer & tickle Archived 2019-04-25 at the Wayback Machine," Prospect Magazine, May 2006

- de Wroblewsky, Clement; Jost, Michael (1986). Wo wir sind ist vorn: der politische Witz in der DDR oder die verschiedenen Feinheiten bzw. Grobheiten einer echten Volkskunst [Where we are is the Front: The Political Joke in the GDR or the Subtlety and Cruelty of Genuine Folk Art] (in German). Rasch und Röhring. ISBN 3-89136-093-2.

- Mueller, Bodo (2016). Lachen gegen die Ohnmacht: DDR-Witze im Visier der Stasi [Laughing against powerlessness: GDR jokes in the Stasi's sights] (in German). Christoph Links. ISBN 978-3861539148.

- Franke, Ingolf (2003). Das grosse DDR-Witz.de-Buch: vom Volk, für das Volk [The Big Book of Jokes from DDR-Witz.de: By the People, for the People] (in German). WEVOS. ISBN 3-937547-00-2.

- Franke, Ingolf (2003). Das zweite grosse DDR-Witze.de Buch [The Second Big Book of Jokes from DDR-Witz.de] (in German). WEVOS. ISBN 3-937547-01-0.

- Rodden, John (2002). Repainting the Little Red Schoolhouse: A History of Eastern German Education, 1945-1995. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511244-X.

East German jokes

View on GrokipediaEast German jokes were subversive oral anecdotes that circulated among citizens of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Soviet-occupied socialist state existing from 1949 to 1990, mocking the regime's economic shortages, bureaucratic absurdities, and repressive apparatus including the Stasi secret police.[1][2] These quips, shared furtively in private settings to evade surveillance, functioned as a low-risk form of dissent, enabling individuals to critique authoritarian leaders like Erich Honecker and the failures of central planning without overt confrontation.[2][3] Punishable by imprisonment under laws against "defeatism," the jokes nonetheless thrived as a coping mechanism, revealing public disillusionment through themes of scarcity—such as rationed bananas or unreliable Trabant vehicles—and ideological hypocrisies, which Western intelligence agencies monitored via intercepted communications to assess regime stability.[2][1] By highlighting systemic contradictions, this humor contributed to the cultural undercurrents of resistance that eroded the GDR's legitimacy, paving the way for the mass protests of 1989.[1][3]

Historical Origins

Post-War Formation of the GDR

Following Germany's unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, the Allied powers divided the defeated nation into four occupation zones: the American, British, French, and Soviet zones, with Berlin similarly subdivided despite its location deep within the Soviet sector.[4] The Potsdam Conference, held from July 17 to August 2, 1945, among leaders of the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union, reaffirmed this zonal division and established guiding principles for Germany, including demilitarization, denazification, democratization, and reparations primarily from the Soviet zone.[4] These arrangements, intended as temporary, entrenched Soviet control over roughly one-third of Germany's territory and population, setting the stage for ideological divergence amid emerging Cold War tensions.[5] In the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ), the Soviet Military Administration imposed rapid transformations, including land reforms redistributing estates from former Nazis and large landowners to peasants, and the nationalization of key industries, which disrupted traditional economic structures and generated early grievances among affected groups.[6] Politically, the communists consolidated power through the formation of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) on April 21-22, 1946, via a coerced merger of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in the SBZ; while presented as voluntary unity, Soviet pressure and intimidation suppressed SPD opposition, ensuring communist dominance within the new party.[7] The SED, under leaders like Walter Ulbricht, became the vanguard of Marxist-Leninist policy, marginalizing non-communist parties and establishing a monopoly on power that tolerated no genuine pluralism.[8] The Western zones' currency reform on June 20, 1948, and the subsequent Berlin Blockade (June 24, 1948–May 12, 1949) accelerated separation, prompting the formation of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) on May 23, 1949, from the three Western zones.[9] In direct response, the Soviet Union oversaw the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) on October 7, 1949, from the SBZ, with a constitution promulgated that day modeling superficial democratic elements on the Weimar Republic while enshrining socialist principles and SED leadership.[10] Wilhelm Pieck was appointed president and Otto Grotewohl prime minister, both SED members, in a government criticized internationally as a Soviet puppet lacking sovereignty.[10] This formalization of a one-party socialist state under tight Soviet oversight created an environment of ideological conformity and suppressed dissent, where private jokes emerged as a covert means to critique the regime's rigidities and failures from inception.[11]Early Development of Political Humor

Political humor in East Germany coalesced in the years immediately following the German Democratic Republic's founding on October 7, 1949, amid the imposition of Soviet-style socialism on a war-ravaged populace. Initial jests arose from the stark disjunction between regime promises of rapid reconstruction and egalitarian prosperity versus the realities of forced collectivization of agriculture—completed by 1952—and nationalization of industries, which disrupted livelihoods and triggered shortages of basic goods like bread and coal. Citizens, drawing on pre-existing German traditions of satirical wit, began circulating oral anecdotes privately to vent frustration over bureaucratic overreach and ideological conformity enforced by the Socialist Unity Party (SED). These early jokes often lampooned Walter Ulbricht, SED General Secretary from 1950, portraying him as a rigid ideologue whose policies prioritized loyalty to Moscow over practical needs; one quip from the early 1950s mocked Ulbricht's cult of personality by likening SED congresses to "elephant graveyards," where old apparatchiks gathered to die off without renewal. The June 1953 workers' uprising, sparked by a 10% production quota hike and suppressed with Soviet tanks, accelerated the proliferation of political satire as a form of covert dissent. Stasi files later documented spikes in joke-telling during this crisis, with informants noting humor as a precursor to organized protest, targeting not only Ulbricht's authoritarianism but also the hypocrisy of party elites who enjoyed privileges unavailable to the masses. By the mid-1950s, as the regime stabilized through purges and amnesty programs, jokes evolved into concise, coded barbs exchanged in factories, barracks, and kitchens—venues where surveillance was harder to maintain. Themes centered on the failure of central planning to deliver on Five-Year Plan goals, such as the 1951-1955 emphasis on heavy industry that neglected consumer goods, leading to anecdotes about "socialist abundance" where queues for meat symbolized equality in deprivation. Western intelligence agencies, including West Germany's BND, began systematically collecting these utterances from defectors and border crossers, amassing evidence that humor indexed underlying societal cynicism toward state propaganda.[2] This nascent tradition persisted despite escalating risks, as the regime's 1950s penal reforms under Article 106 criminalized "anti-state agitation," with joke-tellers facing interrogation or labor camp sentences if reported. Archival analyses of Stasi operations reveal that early efforts to stamp out humor focused on urban intellectuals and workers in Berlin and Leipzig, where satirical circles formed around shared experiences of rationing and housing lotteries. Historians attribute the resilience of these jokes to their ephemerality and reliance on plausible deniability—phrased as "innocent" observations—allowing them to undermine official narratives without direct confrontation. By 1960, as economic pressures mounted ahead of the Berlin Wall's construction, political humor had solidified as an underground vernacular, reflecting causal links between policy failures and popular alienation rather than mere anecdotal folklore.[12]Core Themes and Satirical Targets

Critiques of Socialist Leadership and Ideology

East German jokes targeting socialist leadership frequently lampooned SED figures like Walter Ulbricht and Erich Honecker for their perceived incompetence and subservience to Soviet influence, reflecting public frustration with the disconnect between party rhetoric and governance realities. One such joke from the 1950s depicted early leaders Wilhelm Pieck and Otto Grotewohl receiving a motorless car from Joseph Stalin, who remarked, "You don’t need a motor if you’re already going downhill," satirizing the inevitable decline under socialist direction.[13][14] Telling this joke led to a 1956 conviction for "state-endangering propaganda," illustrating the regime's intolerance for such humor.[13] Later jokes under Honecker's tenure, from 1971 to 1989, extended this critique to personal absurdities and ideological hypocrisy, such as "Why did Erich Honecker get a divorce? Because Brezhnev kisses better than his wife," mocking the ritualistic socialist fraternal kiss and East German dependency on Moscow.[13][14] Another quipped, "Erich Honecker and Erich Mielke want to jump from the top of the East Berlin Television tower. Who do you think will land first? Who cares as long as they jump?" expressing outright contempt for the leadership duo.[14] These anecdotes, often whispered to avoid detection, carried risks of 1–4 years imprisonment under Paragraph 220 for defamation of state organs or Paragraph 106 for anti-state propaganda.[13][14] Jokes also pierced the core tenets of Marxist-Leninist ideology, exposing its failure to deliver promised equality and prosperity. A common refrain stated, "Capitalism is the exploitation of man by man. Socialism? The other way around," inverting official propaganda to highlight how the system burdened ordinary citizens while elites enjoyed privileges.[14] Economic mismanagement was derided in lines like, "What would happen if the desert became socialist? Nothing for a while, then there would be a sand shortage," underscoring the ideological blind spots in central planning that led to chronic scarcities.[14] West German intelligence, via the BND, documented such humor from intercepted communications, using it as a barometer of dissent against the SED's rigid doctrine and Honecker's policies.[2] These satirical barbs, prevalent despite Stasi surveillance involving 91,000 employees and 189,000 informants, revealed underlying skepticism toward the regime's utopian claims.[2]Economic Inefficiencies and Consumer Shortages

East German jokes frequently lampooned the chronic consumer shortages and production inefficiencies inherent in the German Democratic Republic's (GDR) centrally planned economy, which prioritized heavy industry and exports over domestic consumer needs. From the 1950s onward, the GDR experienced persistent deficits in everyday goods, including foodstuffs, clothing, and durable items, as resources were allocated to fulfill state quotas rather than market demands.[15][16] This "shortage economy" (Mangelwirtschaft) resulted in long waiting lists for basic purchases; for instance, acquiring a Trabant automobile required joining a queue that could last 10 to 18 years, reflecting both production bottlenecks and bureaucratic delays.[17][18] Humor often highlighted the absurdity of these scarcities through ironic exaggerations. A prevalent joke quipped: "Why are there no bank robberies in the GDR? Because it takes 12 years to get a getaway car!"—directly mocking the interminable delays for vehicles like the underpowered, plastic-bodied Trabant, which symbolized shoddy craftsmanship and material constraints.[14] Another targeted resource mismanagement: "What would happen if the desert became communist? Nothing at first, then a sand shortage," underscoring how central planning led to inexplicable deficits even in abundant scenarios.[2] These jests circulated orally, evading censorship while conveying the frustration of citizens facing empty shelves despite official propaganda claiming abundance. Trabant-specific satire emphasized quality flaws alongside availability issues. Jokes portrayed the car as comically unreliable, such as: "How do you double the value of a Trabant? Fill it with gasoline," critiquing its meager fuel efficiency and resale worth.[13] Such wit also extended to broader inefficiencies, like agricultural failures yielding jokes about the "four main enemies of GDR farming: spring, summer, autumn, and winter," pointing to systemic underperformance in food production that exacerbated rationing and imports dependency.[19] By the 1980s, intensified shortages in items like coffee—due to hard currency limitations and Comecon trade disruptions—fueled further ridicule, reinforcing public cynicism toward the regime's economic promises.[20][21]The Surveillance Apparatus and Stasi

The Ministry for State Security (MfS), commonly known as the Stasi, was founded on February 8, 1950, as East Germany's primary intelligence and secret police agency, tasked with suppressing internal dissent and maintaining the socialist regime's control.[22] By 1989, the Stasi employed 91,015 full-time personnel and relied on 173,081 unofficial informants (Inoffizielle Mitarbeiter or IMs), resulting in a surveillance density where one officer or informant monitored every 6.5 citizens.[23] This pervasive apparatus infiltrated workplaces, schools, churches, and families, fostering widespread paranoia that jokes frequently lampooned as an inescapable web of betrayal and eavesdropping. East German humor targeting the Stasi emphasized the omnipresence of spies and the erosion of private life, often portraying informants as ubiquitous and comically inept yet dangerously effective. One common joke illustrated the Stasi's presumed omniscience: "Why do Stasi officers make such good taxi drivers? Because you get in the car and they already know your name and where you live."[13] Such quips reflected the reality of IMs embedded in everyday settings, including neighbors reporting on each other, with Stasi files documenting over 6 million individuals by the regime's end.[23] Jokes also satirized interrogation tactics and the Stasi's brutal methods, underscoring the psychological toll of constant suspicion. For instance: "The CIA, KGB, and Stasi compete to determine the age of a skeleton in a cave. The CIA uses carbon dating for a precise estimate; the KGB declares it 5,000 years old from the correct era; the Stasi identifies it as Erich Honecker and beats it until it confesses."[24] This highlighted the Stasi's reputation for coercion, as evidenced by its maintenance of 111 million pages of records on perceived threats, often fabricated to justify repression.[23] Under Erich Mielke's leadership from 1957 to 1989, the Stasi expanded into psychological operations like Zersetzung, covertly destabilizing dissidents through character assassination and social isolation, themes echoed in jokes about invisible enemies.[25] A typical example mocked informant reliability: "A Stasi officer asks a passerby, 'How do you assess the political situation?' The man replies, 'I think...' and is immediately arrested for counter-revolutionary thoughts."[26] These anecdotes, circulated orally to evade detection, revealed public awareness of the Stasi's role in stifling free expression, with telling such jokes punishable by imprisonment under Article 106 of the GDR Criminal Code for "agitation against the state."[13]State Responses and Repression

Legal Mechanisms and Punishments

The German Democratic Republic (GDR) prosecuted individuals for disseminating political jokes deemed subversive under provisions of the Strafgesetzbuch der DDR (Criminal Code of the GDR), particularly §106, which criminalized "agitation against the social order" (Hetze gegen die gesellschaftliche Ordnung) with penalties up to 10 years' imprisonment for actions interpreted as undermining the state's socialist foundations. Jokes mocking leaders, ideology, or institutions were often classified as such agitation if shared publicly or with multiple hearers, as they were viewed by authorities as fostering discontent and resistance.[27] Additionally, §220 addressed defamation of the state or its representatives, providing another basis for charges when humor targeted figures like Erich Honecker or Erich Mielke.[14] The Ministry for State Security (Stasi) played a central role in enforcement through informant networks—numbering around 189,000 full-time operatives and unofficial collaborators—who reported suspected joke-tellers, often leading to investigations under operations like "DDR-Witz," which systematically collected and analyzed anti-regime humor to identify perpetrators and assess public morale.[28] Upon a report, the Stasi interrogated both the teller and witnesses, using psychological pressure to extract confessions; hearers could face complicity charges, as illustrated in anecdotal cases where listeners received sentences for failing to report the joke.[29] Trials were conducted by state courts, with convictions relying on Stasi dossiers that framed jokes as evidence of broader political unreliability rather than isolated offenses, though researchers note that humor directly precipitated many prosecutions.[13] Punishments typically involved imprisonment, with sentences ranging from one to four years, alongside professional sanctions such as job loss or expulsion from the Socialist Unity Party (SED). Historian Bodo Müller, analyzing Stasi archives, documented approximately 100 cases of individuals targeted for political jokes from the 1960s to 1980s, resulting in 64 convictions; most served 1–3 years in labor camps or prisons like Bautzen, while one case extended to 4.5 years for repeated offenses.[14] [13] These measures aimed to deter dissent, though enforcement was selective, prioritizing those with influence or in sensitive positions, and often amplified by informal Stasi tactics like Zersetzung (decomposition), which eroded suspects' social and psychological stability without formal trial.[2]Surveillance Operations Including DDR-Witz

The Ministry for State Security (MfS), known as the Stasi, implemented comprehensive surveillance to identify and neutralize perceived threats to the German Democratic Republic (GDR), including the telling of political jokes termed DDR-Witze. Established on February 8, 1950, the Stasi developed an informant network exceeding 170,000 unofficial collaborators by the 1980s, who documented private conversations across factories, schools, and residences for signs of dissent.[25] [30] These operations treated DDR-Witze—satirical quips targeting leaders like Erich Honecker or systemic failures—as indicators of ideological unreliability, often triggering further investigation.[27] Under Paragraph 106 of the GDR Criminal Code, enacted in 1968, propagating "state-endangering propaganda agitation" encompassed joke-telling that defamed the socialist state or its representatives, with penalties up to five years imprisonment, extendable to eight for aggravated cases. Stasi guidelines directed informants to report such humor verbatim, leading to interrogations where suspects faced pressure to confess or implicate others. House searches frequently uncovered no physical evidence beyond informant testimony, yet sufficed for prosecution.[14][25] Archival examinations post-reunification reveal hundreds of convictions tied to DDR-Witze. In a sample of 100 documented cases from Stasi files, 64 individuals received prison terms averaging one to three years for verbal jokes alone, demonstrating the regime's intolerance for even whispered satire.[13] Broader Stasi efforts integrated joke monitoring into routine "operational proceedings" against potential subversives, with departments like Main Department XX/4 focusing on ideological violations. This approach amplified self-censorship, as citizens knew casual remarks could result in career sabotage, travel bans, or incarceration.[25] While no singular Stasi operation exclusively targeted DDR-Witze, surveillance fused with repression tactics like psychological decomposition—Zersetzung—to isolate tellers through social ostracism or fabricated scandals. By 1989, amid mounting dissent, such measures failed to stem joke circulation, underscoring their role in sustaining morale against omnipresent monitoring.[31][27]Cultural Role and Interpretations

Functions as Coping Mechanism and Subtle Resistance

East German jokes functioned primarily as a psychological outlet for citizens enduring the GDR's systemic inefficiencies, material shortages, and ideological impositions, allowing individuals to articulate frustrations in a semi-anonymous manner that mitigated immediate reprisal risks. By ridiculing everyday absurdities—such as chronic consumer goods deficits or the Trabant automobile's unreliability—humor provided emotional relief and a temporary sense of agency in a society where open criticism could lead to imprisonment under Paragraph 220 of the criminal code for "anti-state agitation." Historians note that this form of levity helped maintain mental resilience amid pervasive surveillance by the Ministry for State Security (Stasi), which documented over 100,000 joke-related files yet failed to eradicate the practice, as evidenced by collections amassed by West German intelligence during the Cold War.[32][1][14] As subtle resistance, these jokes eroded the regime's aura of infallibility by exposing contradictions between socialist propaganda and lived reality, often circulated orally in trusted private circles to evade detection and foster informal networks of dissent. Unlike overt protests, which invited swift Stasi intervention—such as the 1972 sentencing of three engineers to prison for joke-telling—humor's indirect satire on leaders like Erich Honecker or the Stasi's omnipresence allowed for critique without explicit calls to action, thereby sustaining a cultural undercurrent of skepticism toward SED authority. Academic analyses emphasize that this transmission via whispered anecdotes or satirical magazines like Eulenspiegel (established 1961) reflected broader cynicism, subtly challenging state narratives on economic progress and Soviet loyalty while building communal solidarity among skeptics.[14][32][1]Debates on Effectiveness and Societal Impact

Scholars debate whether East German political jokes primarily functioned as a safety valve for public frustration, dissipating tension without challenging the regime's authority, or as a form of subtle subversion that eroded ideological legitimacy over time.[33] Proponents of the safety valve theory argue that the jokes allowed citizens to express discontent in a controlled, oral manner, preventing escalation into organized opposition by providing psychological relief amid economic shortages and surveillance. This perspective posits that their ephemeral nature—shared privately and rarely documented—limited their disruptive potential, serving instead as a substitute for political participation in a repressive system.[34] Conversely, analyses emphasizing subversion highlight how the jokes fostered cynicism toward socialist leadership and institutions, contributing to a gradual delegitimization of the state. Historian Ben Lewis contends that such humor, by ridiculing figures like Erich Honecker and exposing systemic absurdities, played a role in the moral and ideological decay that culminated in the 1989 revolution, as widespread derision undermined the regime's aura of infallibility.[35] Empirical evidence from Stasi archives supports this view: the Ministry for State Security systematically monitored and prosecuted joke-tellers under Article 106 of the penal code for "agitation against the state," with operations targeting over 1,000 cases annually by the 1980s, indicating the authorities perceived them as a genuine threat to social cohesion.[2] Bodo Müller's examination of Stasi files reveals that jokes were used as a "mood barometer" by intelligence, with informants infiltrating social circles to suppress dissemination, yet their persistence—estimated at tens of thousands circulating orally—suggests they built informal networks of dissent. On societal impact, the jokes demonstrably aided coping mechanisms in a society facing chronic material deprivation and ideological enforcement, with surveys post-reunification indicating that 70-80% of former East Germans recalled sharing or hearing them as a means of bonding and resilience against isolation.[29] They cultivated a culture of ironic detachment, which some researchers link to the rapid mobilization during the Peaceful Revolution, as habitual skepticism toward official narratives facilitated mass protests in Leipzig and Berlin starting September 1989.[1] However, quantitative assessments remain elusive, with no direct causal data tying joke prevalence to regime collapse; instead, their role appears amplificatory, exacerbating low morale amid external pressures like Gorbachev's perestroika. Critics of overattribution note that while jokes reflected discontent—peaking during crises like the 1977 expatriation of dissidents—they did not mobilize action, as most remained passive commentary rather than calls to organize. Overall, their dual valence as both vent and critique underscores a nuanced legacy, where limited individual risk belied cumulative effects on collective psyche.[33]Examples

Political and Ideological Jokes

Political and ideological jokes in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) targeted the Socialist Unity Party (SED) leadership and the Marxist-Leninist ideology underpinning the state, exposing contradictions between official propaganda and lived realities. These quips often portrayed figures like General Secretary Erich Honecker or Stasi head Erich Mielke as incompetent or hypocritical, while mocking core tenets such as proletarian internationalism and the superiority of socialism over capitalism. Circulation occurred orally in private settings due to severe risks; the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) classified joke-telling as "defamation of the state," leading to surveillance, arrests, and imprisonments of up to three years, with at least 64 convictions documented from monitored cases in the 1980s.[13] A 1956 court case exemplified early repression: a man faced trial for a joke depicting SED leaders Wilhelm Pieck and Otto Grotewohl receiving a motorkess car from Joseph Stalin, symbolizing the GDR's dependency on Soviet directives and lack of autonomy—"You don’t need a motor if you’re already going downhill."[13] Honecker himself featured prominently, as in a quip referencing his public displays of loyalty to Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev: "Why did Erich Honecker get a divorce? Because Brezhnev kisses better than his wife," satirizing subservience to Moscow over domestic priorities.[13] Ideological critiques inverted regime slogans, such as: "Capitalism is the exploitation of man by man. Under socialism, it is exactly the other way around," underscoring perceived elite privileges amid widespread privation.[13] Another targeted the SED Politburo: "What has 8 teeth and 52 legs? The SED Politburo," portraying the leadership as predatory and detached insects devouring societal resources.[33] Jokes also lampooned Honecker's cult of personality, like: "What’s the difference between Honecker and a streetcar? The streetcar has more followers," highlighting superficial popularity engineered by state media.[24] Further examples questioned socialist orthodoxy, such as Honecker joining a queue only to learn it was for exit visas: "Na, wenn du einen Ausreiseantrag stellst, können wir ja alle hierbleiben!" (If you apply for an exit visa, we can all stay here!), implying mass desire to flee under his rule.[33] The "seven A's of socialism"—standing for attributes like "All work dumped on others, then blame them"—encapsulated cynicism toward collective responsibility and ideological work ethic.[24] West German intelligence (BND) collected such jokes from intercepted communications to assess dissent levels, declassifying files post-reunification that revealed their prevalence as subtle indicators of ideological disillusionment.[33]Economic and Everyday Life Jokes

East German jokes targeting economic conditions and daily hardships underscored the Mangelwirtschaft, a persistent shortage economy where consumer goods, housing, and even basic foodstuffs were rationed or unavailable despite state propaganda touting socialist plenty. These quips arose from real scarcities, including wait times averaging 10 to 13 years for items like the Trabant automobile, the GDR's primary passenger car produced from 1963 to 1991.[36] [37] Everyday inefficiencies, such as interminable queues for meat or toilet paper, fueled humor that exposed the gap between official ideology and lived reality, often collected by Western intelligence from intercepted communications.[2] Jokes about the Trabant epitomized frustration with shoddy manufacturing and distribution failures. One mocked its unreliability: "What’s the best feature of a Trabant? There’s a heater at the back to keep your hands warm when you’re pushing it."[14] [13] Another highlighted its pollution: "What is the longest car on the market? The Trabant, at 12 meters length: 2 meters of car, plus ten meters of smoke."[14] Broader scarcity inspired absurd extrapolations of planning failures. "What would happen if the desert became communist? Nothing for a while, and then there would be a sand shortage," satirized how central directives led to irrational deficits, even hypothetically.[2] [14] Similarly, "Did East Germans originate from apes? Impossible. Apes could never have survived on just two bananas a year," lampooned import-dependent luxuries like tropical fruit, doled out sparingly via state allocations.[2] Daily banalities drew biting wit on bureaucratic hurdles and substandard goods. "Why are there no bank robberies in the GDR? Because you have to wait 12 years for a get-away car," directly referenced Trabant delivery delays.[14] Toilet paper shortages prompted: "Why is toilet paper so rough in the GDR? In order to make the last asshole red," reflecting coarse, low-quality substitutes often endured.[14] Such humor, risking Stasi scrutiny, circulated orally as veiled critique of systemic unresponsiveness to consumer needs.[2]Stasi and Leadership-Specific Jokes

Jokes targeting the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) and Socialist Unity Party (SED) leaders, particularly General Secretary Erich Honecker and Stasi head Erich Mielke, emphasized the apparatus's extensive surveillance and the leaders' perceived arrogance or incompetence. These quips, often shared in whispers among trusted circles, highlighted the Stasi's role in suppressing dissent, including through monitoring political humor deemed "state-defaming agitation" under Paragraph 106 of the GDR Criminal Code, which carried penalties of up to five years imprisonment.[29] The Stasi maintained specialized departments, such as Main Department XX/4, to catalog jokes from informant reports, using them as evidence in over 1,000 convictions related to verbal offenses between 1968 and 1989.[33] A prevalent motif involved dialogues between Honecker and Mielke, satirizing their shared responsibility for repression. In one such anecdote, Honecker remarks on collecting all circulating jokes about himself, to which Mielke responds, "Well, we have almost the same hobby. I collect all those who tell jokes about you." This underscores the Stasi's informant network, which by 1989 encompassed approximately 173,000 unofficial collaborators monitoring everyday conversations.[14]Honecker and Mielke discuss their predicament during a power outage: Honecker is trapped in an elevator with his secretary, while Mielke stands alone on a stationary escalator. Mielke asks why Honecker seems distressed; Honecker replies that at least he has company, unlike Mielke who is "alone with his thoughts."[24]Such humor portrayed Mielke's isolation as emblematic of the Stasi's paranoid efficiency. Another joke mocked Stasi interrogation prowess: A skeleton is submitted for age determination via forensic methods, but the Stasi agent "interrogates" it to extract the precise figure of 845,792 years, parodying coercive tactics that yielded confessions regardless of evidence.[24] Stasi ubiquity featured in tales of everyday intrusion, like: "Why do Stasi officers make good taxi drivers? You get in the car and they already know your name and where you live." This reflected the reality of files on up to one-third of the population, amassed through wiretaps, mail interception, and neighborhood spies.[14] Operational groups of three were lampooned as requiring one to read, one to write, and one to supervise the "intellectuals," critiquing bureaucratic redundancy amid the Stasi's 91,000 full-time employees by 1989.[14] Leadership follies appeared in afterlife scenarios, such as Honecker arriving at heaven's gate burdened by a rucksack of sins, which two devils later claim as "political refugees" fleeing judgment, alluding to the regime's export of dissidents and Honecker's 18-year tenure marked by fortified borders and suppressed satire.[24] Despite censorship, these jokes persisted as subtle indictments, with Stasi archives post-reunification revealing thousands of documented instances, though many evaded detection through oral tradition.[33]