Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Erich Honecker

View on Wikipedia

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (German: [ˈeːʁɪç ˈhɔnɛkɐ]; 25 August 1912 – 29 May 1994)[7] was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the posts of General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) and Chairman of the National Defence Council; in 1976, he replaced Willi Stoph as Chairman of the State Council, the official head of state. As the leader of East Germany, Honecker was viewed as a dictator.[8][9][10] During his leadership, the country had close ties to the Soviet Union, which maintained a large army in the country.

Key Information

Honecker's political career began in the 1930s when he became an official of the Communist Party of Germany, a position for which he was imprisoned by the Nazis. Following World War II, he was freed by the Soviet army and relaunched his political activities, founding the SED's youth organisation, the Free German Youth, in 1946 and serving as the group's chairman until 1955. As the Security Secretary of the SED Central Committee, he was the prime organiser of the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 and, in this function, bore administrative responsibility for the "order to fire" along the Wall and the larger inner German border.

In 1970, Honecker initiated a political power struggle that led, with support of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, to him replacing Walter Ulbricht as General Secretary of the SED and chairman of the National Defence Council. Under his command, the country adopted a programme of "consumer socialism" and moved towards the international community by normalising relations with West Germany and also becoming a full member of the UN, in what is considered one of his greatest political successes. As Cold War tensions eased in the late 1980s with the advent of perestroika and glasnost—the liberal reforms introduced by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev—Honecker refused all but cosmetic changes to the East German political system. He cited the consistent hardliner attitudes of Kim Il Sung, Fidel Castro and Nicolae Ceaușescu whose respective governments of North Korea, Cuba and Romania had been critical of reforms. Honecker was forced to resign by the SED Politburo in October 1989 in a bid to improve the government's image in the eyes of the public; the effort was unsuccessful, and the regime would collapse entirely the following month.

Following German reunification in 1990, Honecker sought asylum in the Chilean embassy in Moscow, but was extradited back to Germany in 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union, to stand trial for his role in the human rights abuses committed by the East German government. However, the proceedings were abandoned, as Honecker was suffering from terminal liver cancer. He was freed from custody to join his family in exile in Chile, where he died in May 1994.

Childhood and youth

[edit]Honecker was born into a deeply Protestant family in Neunkirchen,[11] in what is now Saarland, to Wilhelm Honecker (1881–1969), a coal miner and political activist,[12] and his wife Caroline Catharine Weidenhof (1883–1963). The couple, married in 1905, had six children. Erich, their fourth child, was born on 25 August 1912 during the period in which the family resided on Max-Braun-Straße, before later moving to Kuchenbergstraße 88 in the present-day Neunkirchen city district of Wiebelskirchen.

After World War I, the Territory of the Saar Basin was occupied by France. This change from the strict rule of Ferdinand Eduard von Stumm to French military occupation provided the backdrop for what Wilhelm Honecker understood as proletarian exploitation, and introduced young Erich to communism.[12] After his tenth birthday in 1922, Erich Honecker became a member of the Spartacus League's children's group in Wiebelskirchen.[12] Aged 14 he entered the KJVD, the Young Communist League of Germany, for whom he later served the organisation's leader of Saarland from 1931.[13]

Honecker did not find an apprenticeship immediately after leaving school, but instead worked for a farmer in Pomerania for almost two years.[14] In 1928 he returned to Wiebelskirchen and began a traineeship as a roofer with his uncle, but quit to attend the International Lenin School in Moscow and Magnitogorsk after the KJVD handpicked him for a course of study there.[15] There, sharing a room with Anton Ackermann,[16] he studied under the cover name "Fritz Malter".[17]

Opposition to the Nazis and imprisonment

[edit]In 1930, aged 18, Honecker entered the KPD, the Communist Party of Germany.[18] His political mentor was Otto Niebergall, who later represented the KPD in the Reichstag. After returning from Moscow in 1931 following his studies at the International Lenin School, he became the leader of the KJVD in the Saar region. After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, Communist activities within Germany were only possible undercover; the Saar region however still remained outside the German Reich under a League of Nations mandate. Honecker was arrested in Essen, Germany, but soon released. Following this, he fled to the Netherlands and from there oversaw KJVD's activities in Pfalz, Hesse and Baden-Württemberg.[14]

Honecker returned to the Saar in 1934 and worked alongside Johannes Hoffmann on the campaign against the region's re-incorporation into Germany. A referendum on the area's future in January 1935 however saw 90.73% vote in favour of reunifying with Germany. Like 4,000 to 8,000 others, Honecker then fled the region, initially relocating to Paris.[14]

On 28 August 1935 he illegally travelled to Berlin under the alias "Marten Tjaden", with a printing press in his luggage. From there he worked closely together with KPD official Herbert Wehner in opposition/resistance to the Nazi state. On 4 December 1935 Honecker was detained by the Gestapo and until 1937 remanded in Berlin's Moabit detention centre. On 3 July 1937 he was sentenced to ten years imprisonment for the "preparation of high treason alongside the severe falsification of documents".[18][19]

Honecker spent the majority of his incarceration in the Brandenburg-Görden Prison, where he also carried out tasks as a handyman.[14] In early 1945, he was moved to the Barnimstrasse women's prison in Berlin due to good behaviour and to be put to work repairing the bomb-damaged building, as he was a skilled roofer.[20] During an Allied bombing raid on 6 March 1945, he managed to escape and hid himself at the apartment of Lotte Grund, a female prison guard. After several days she persuaded him to turn himself in, and his escape was then covered up by the guard.

After the liberation of the prisons by advancing Soviet troops on 27 April 1945, Honecker remained in Berlin.[21] His "escape" from prison and his relationships during his captivity later led to his experiencing difficulties within the Socialist Unity Party, as well as straining his relations with his former inmates. In later interviews and in his personal memoirs, Honecker falsified many of the details of his life during this period.[22][23] Material from the East German State Security Service has been used to allege that, to be released from prison, Honecker offered the Gestapo evidence incriminating fellow imprisoned Communists, claimed he had renounced communism "for good", and was willing to serve in the German army.[24]

Post-war return to politics

[edit]

In May 1945 Honecker was "picked up" by chance in Berlin by Hans Mahle and taken to the Ulbricht Group, a collective of exiled German communists that had returned from the Soviet Union to Germany after the end of the Nazi regime.[25] Through Waldemar Schmidt, Honecker befriended Walter Ulbricht, who had not been aware of him at that point. Honecker's future role in the group was still undecided until well into the summer months, as he had yet to face a party process. This ended in a reprimand due to his "undisciplined conduct" in fleeing from prison at the start of the year, an action which was debated upon, potentially jeopardising the other (communist) inmates.[21][26]

In 1946, Honecker became the co-founder of the Free German Youth (FDJ), whose chairmanship he also undertook. After the formation of the SED, the Socialist Unity Party, in April 1946 through a merger of the KPD and SPD, Honecker swiftly became a leading party member and took his place in the party's Central Committee.

On 7 October 1949, the German Democratic Republic was formed with the adoption of a new constitution, establishing a political system similar to that of the Soviet Union. Within the state's socialist single party government, Honecker determinedly resumed his political career and the following year was named as a candidate member of the Politbüro of the SED's Central Committee.[25] As President of the Free German Youth movement, he organised the inaugural "Deutschlandtreffen der Jugend" in East Berlin in May 1950 and the 3rd World Festival of Youth and Students in 1951, although the latter was beset with organisational problems.[25]

During the internal party unrest following the suppressed uprising of June 1953, Honecker sided with First Secretary Walter Ulbricht, despite the majority of the Politburo attempting to depose Ulbricht in favour of Rudolf Herrnstadt.[27] Honecker himself though faced questioning from party members about his inadequate qualifications for his position. On 27 May 1955 he handed the Presidency of the FDJ over to Karl Namokel, and departed for Moscow to study for two years at the School of the Soviet Communist Party at Ulbricht's request.[18] During this period he witnessed the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in person, where its First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev denounced Joseph Stalin.[19]

After returning to East Germany in 1958, Honecker became a fully-fledged member of the Politburo, taking over responsibility for military and security issues.[28] As the Party Security Secretary he was the prime organiser of the building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 and also a proponent of the "order to fire" along the Inner German border.[29]

Leadership of East Germany

[edit]

While Ulbricht had replaced the state's command economy with, firstly the "New Economic System", then the Economic System of Socialism, as he sought to improve the country's failing economy, Honecker declared the main task under his New System of Economic Socialism to in fact be the "unity of economic and social politics", essentially through which living standards (with increased consumer goods) would be raised in exchange for political loyalty.[30][31] Tensions had already led to his once-mentor Ulbricht removing Honecker from the position of Second Secretary in July 1970, only for the Soviet leadership to swiftly reinstate him.[28] Honecker played up the thawing East-West German relationship as Ulbricht's strategy, to win the support of the Soviet leadership under Leonid Brezhnev.[28] With this secured, Honecker was appointed First Secretary (from 1976 titled general secretary) of the Central Committee on 3 May 1971 after the Soviet leadership forced Ulbricht to step aside "for health reasons".[28][32]

After also succeeding Ulbricht as Chairman of the National Defence Council in 1971,[33] Honecker was eventually also elected Chairman of the State Council (a post equivalent to that of president) on 29 October 1976.[34] With this, Honecker reached the height of power within East Germany. From there on, he, along with Economic Secretary Günter Mittag and Minister of State Security Erich Mielke, made all key government decisions. Until 1989 the "little strategic clique" composed of these three men was unchallenged as the top level of East Germany's ruling class.[35] Honecker's closest colleague was Joachim Herrmann, the SED's Agitation and Propaganda Secretary. Alongside him, Honecker held daily meetings concerning the party's media representation in which the layout of the party's own newspaper Neues Deutschland, as well as the sequencing of news items in the national news bulletin Aktuelle Kamera, were determined.[36]

Under Honecker's leadership, East Germany adopted a programme of "consumer socialism", which resulted in a marked improvement in living standards already the highest among the Eastern bloc countries – though still far behind West Germany. More attention was placed on the availability of consumer goods, and the construction of new housing was accelerated, with Honecker promising to "settle the housing problem as an issue of social relevance".[37] His policies were initially marked by a liberalisation toward culture and art. While 1973 brought the World Festival of Youth and Students to East Berlin, soon dissident artists such as Wolf Biermann were expelled and the Ministry for State Security raised its efforts to suppress political resistance. Honecker remained committed to the expansion of the Inner German border and the "order to fire" policy along it.[38] During his time in the office around 125 East German citizens were killed while trying to reach the West.[39]

After the Federal Republic had secured an agreement with the Soviet Union on cooperation and a policy of non-violence, it became possible to reach a similar agreement with the GDR. The Basic Treaty between East and West Germany in 1972 sought to normalise contacts between the two governments.

East Germany also participated in the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe held in Helsinki in 1975, which attempted to improve relations between the West and the Eastern Bloc, and became a full member of the United Nations.[40] These acts of diplomacy were considered Honecker's greatest successes in foreign politics.

Honecker received additional high-profile personal recognitions including honorary doctorates of business administration from East Berlin's Humboldt University in 1976, Tokyo's Nihon University in 1981 and the London School of Economics in 1984 and the Olympic Order from the IOC in 1985. In September 1987, he became the first East German head of state to visit West Germany, where he was received with full state honours by West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl in an act that seemed to confirm West Germany's acceptance of East Germany's existence. During this trip he also journeyed to his birthplace in Saarland, where he held an emotional speech in which he spoke of a day when Germans would no longer be separated by borders.[29] This trip had been planned twice before, including September 1984,[41] but was initially blocked by the Soviet leadership which mistrusted the special East-West German relationship,[42] particularly efforts to expand East Germany's limited independence in the realm of foreign policy.[43]

Illness, downfall and resignation

[edit]In the late 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced glasnost and perestroika, reforms to liberalise the socialist planned economy. Frictions between him and Honecker had grown over these policies and numerous additional issues from 1985 onward.[44] East Germany refused to implement similar reforms, with Honecker reportedly telling Gorbachev: "We have done our perestroika; we have nothing to restructure".[45][46] Gorbachev grew to dislike Honecker, and by 1988 was lumping him in with Bulgaria's Todor Zhivkov, Czechoslovakia's Gustáv Husák and Romania's Nicolae Ceaușescu as a "Gang of Four": a group of inflexible hardliners unwilling to make reforms.[47]

According to White House experts Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice, Gorbachev looked to Communist leaders in Eastern Europe to follow his example of perestroika and glasnost. They argue:

- Gorbachev himself had no particular sympathy for Erich Honecker, chairman of the East German Communist Party, and his hard-line comrades and the government. As early as 1985... [Gorbachev] had told East German party officials that kindergarten was over; no one would lead them by the hand. They were responsible for their own people. The relations between Gorbachev and Honecker went downhill from there.[48]

Western analysts, according to Zelikow and Rice, believed in 1989 that Communism was still secure in East Germany:

- Bolstered by relatively greater affluence than his country's Eastern European neighbours enjoyed in a fantastically elaborate system of internal controls, East Germany's longtime leader Eric Honecker seemed secure in his position. His government had long dealt with dissent through a mixture of brutal repression, forced emigration, and the vent of allowing occasional, limited travel to the West for a substantial part of the population.[49]

Honecker felt betrayed by Gorbachev in his German policy and ensured that official texts of the Soviet Union, especially those concerning perestroika, could no longer be published or sold in East Germany.[50]

One month after the 1989 Polish legislative election in which Lech Wałęsa and the Solidarity Citizens' Committee unexpectedly won 99 out of 100 seats, at the Warsaw Pact summit on 7–8 July 1989 in Bucharest, the Soviet Union reaffirmed its shift from the Brezhnev Doctrine of the limited sovereignty of its member states, and announced "freedom of choice".[51][52][53] The Bucharest statement prescribed that its signatories henceforth developed their "own political line, strategy and tactics without external intervention".[54] This called into question the Soviet guarantee of existence for the Communist states in Europe. Already in May 1989 Hungary had begun dismantling its border with Austria, creating the first gap in the so-called Iron Curtain, through which later several thousand East Germans quickly fled in hopes of reaching West Germany by way of Austria.[55] But with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic in August 1989 (which was based on an idea by Otto von Habsburg to test Gorbachev's reaction to the opening of the border),[56] the subsequent hesitant behaviour of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the non-intervention of the Soviet Union opened the floodgates. Thus the united front of the Eastern Bloc was broken. The reaction to this from Erich Honecker in the Daily Mirror of 19 August 1989 was too late and showed the current loss of power: "Habsburg distributed leaflets far into Poland, on which the East German holidaymakers were invited to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given gifts, food and Deutsche Mark, and then they were persuaded to come to the West." Later, after his fall, Honecker said of Otto von Habsburg in connection with the summer of 1989: "That this Habsburg drove the nail into my coffin."[57] Now tens of thousands of media-informed East Germans made their way to Hungary, which was no longer ready to keep its borders completely closed or to oblige its border troops to use force of arms.[58][59][60] A 1969 treaty required the Hungarian government to send the East Germans back home;[47] however, starting on 11 September 1989, the Hungarians let them pass into Austria,[61] telling their outraged East German counterparts that they were refugees and that international treaties on refugees took precedence.

At the time, Honecker was sidelined through illness, leaving his colleagues unable to act decisively. He had been taken ill with biliary colic during the Warsaw Pact summit. He was shortly afterwards flown home to East Berlin.[47][54] After an initial stabilisation in his health, he underwent surgery on 18 August 1989 to remove his inflamed gallbladder and, due to a perforation, part of his colon.[62][63] According to the urologist Peter Althaus, the surgeons left a suspected carcinogenic nodule in Honecker's right kidney due to his weak condition, and also failed to inform the patient of the suspected cancer;[64] other sources say the tumour was simply undetected. As a result of this operation, Honecker was away from his office until late September 1989.[65][66]

Back in office, Honecker had to contend with the rising number and strength of demonstrations across East Germany that had first been sparked by reports in the West German media of fraudulent results in local elections on 7 May 1989,[47][67] the same results he had labelled a "convincing reflection" of the populace's faith in his leadership.[68] He also had to deal with a new refugee problem. Several thousand East Germans tried to go to West Germany by way of Czechoslovakia, only to have that government bar them from passing. Several thousands of them headed straight for the West German embassy in Prague and demanded safe passage to West Germany. With some reluctance, Honecker allowed them to go – but forced them to go back through East Germany on sealed trains and stripped them of their East German citizenship. Several members of the SED Politbüro realised this was a serious blunder and made plans to get rid of him.[47]

As unrest visibly grew, large numbers began fleeing the country through the West German embassies in Prague and Budapest, as well as over the borders of the "socialist brother" states.[69][70] Each month saw tens of thousands more exit.[71][72] On 3 October 1989 East Germany closed its borders to its eastern neighbours and prevented visa-free travel to Czechoslovakia;[73] a day later these measures were also extended to travel to Bulgaria and Romania. East Germany was now not only behind the Iron Curtain to the West, but also cordoned off from most other Eastern bloc states.[74]

On 6–7 October 1989 the national celebrations of the 40th anniversary of the East German state took place with Gorbachev in attendance.[75] To the surprise of Honecker and the other SED leaders in attendance, several hundred members of the Free German Youth — reckoned as the future vanguard of the party and nation — began chanting, "Gorby, help us! Gorby, save us!".[76] In a private conversation between the two leaders Honecker praised the success of the country, but Gorbachev knew that, in reality, it faced bankruptcy;[47][77] East Germany had already accepted billions of dollars in loans from West Germany during the decade as it sought to stabilise its economy.[78] Attempting to make Honecker accept a need for reforms, Gorbachev warned Honecker that "He who is too late is punished by life", yet Honecker maintained that "we will solve our problems ourselves with socialist means".[76] Protests outside the reception at the Palace of the Republic led to hundreds of arrests in which many were brutally beaten by soldiers and police.[76]

Being able to have an apartment, a job, clothes to put on, something to eat, and not having to sleep under bridges: that was already, for Erich Honecker, socialism.

— Hans Modrow, 2005.[79]

As the reform movement spread throughout Central and Eastern Europe, mass demonstrations against the East German government erupted, most prominently in Leipzig—the first of several demonstrations which took place on Monday nights across the country. In response, an elite paratroop unit was dispatched to Leipzig—almost certainly on Honecker's orders, since he was commander-in-chief of the Army. A bloodbath was averted only when local party officials themselves ordered the troops to pull back. In the following week, Honecker faced a torrent of criticism. This gave his Politburo comrades the impetus they needed to replace him.[47]

After a crisis meeting of the Politburo on 10–11 October 1989, Honecker's planned state visit to Denmark was cancelled and, despite his resistance, at the insistence of the regime's number-two-man, Egon Krenz, a public statement was issued that called for "suggestions for attractive socialism".[80] Over the following days Krenz worked to secure himself the support of the military and the Stasi and arranged a meeting between Gorbachev and Politburo member Harry Tisch, who was in Moscow, to inform the Kremlin about the now-planned removal of Honecker;[81] Gorbachev reportedly wished them good luck.[82]

The sitting of the SED Central Committee planned for the end of November 1989 was pulled forward a week, with the most urgent item on the agenda now being the composition of the Politburo. Krenz and Mielke attempted by telephone on the night of 16 October to win other Politburo members over to remove Honecker. At the beginning of the session on 17 October, Honecker asked his routine question of "Are there any suggestions for the agenda?"[83] Stoph replied, "Please, general secretary, Erich, I propose that a new item be placed on the agenda. It is the release of Comrade Erich Honecker as general secretary and the election of Comrade Egon Krenz in his place."[47] Honecker reportedly calmly responded: "Well, then I open the debate".[84]

All those present then spoke, in turn, but none in favour of Honecker.[84] Günter Schabowski even extended the dismissal of Honecker to also include his posts in the State Council and as Chairman of the National Defence Council while childhood friend Günter Mittag moved away from Honecker.[83] Mielke, hollering and pounding the conference room table with his fist pointed at Honecker and blamed him for almost all the country's current ills and threatened to publish compromising information that he possessed, if Honecker refused to resign.[85] A ZDF documentary on the matter claims this information was contained in a large red briefcase found in Mielke's possession in 1990.[86] After three hours the Politburo voted to remove Honecker.[84][87] In accordance with longstanding practice, Honecker voted for his own removal.[47] As a concession to Honecker, he was allowed to publicly save face by resigning due to "ill health".[88] Krenz was unanimously elected as his successor as General Secretary.[89][90] This closely echoed how Honecker helped force Ulbricht out 18 years earlier; he too had been publicly allowed to retire for health reasons.

Start of prosecution and asylum attempts

[edit]

Three weeks after Honecker's ousting the Berlin Wall fell, and the SED swiftly lost control of the country. On 1 December, the Volkskammer deleted the provisions in the East German constitution giving the SED a monopoly on power, thus formally ending Communist rule in East Germany two months after Honecker's removal. In an effort to rehabilitate itself, the SED expelled Honecker and several other former officials two days later.[91] He went on to join the newly founded Communist Party of Germany in 1990, remaining a member until his death.[92]

During November the Volkskammer had already set up a committee to investigate corruption and abuses of office, with Honecker being alleged to have received annual donations from the National Academy of Architecture of around 20,000 marks as an "honorary member".[93][94] On 5 December 1989 the chief public prosecutor in East Germany formally launched a judicial inquiry against him on charges of high treason, abuses of confidence and embezzlement to the serious disadvantage of socialist property[95] (the charge of high treason was dropped in March 1990).[96] As a result, Honecker was placed under house arrest for a month.[97]

Following the lifting of his house arrest, Honecker and his wife Margot were forced to vacate their apartment in the Waldsiedlung housing area in Wandlitz, exclusively used by senior SED party members, after the Volkskammer decided to put it to use as a sanatorium for the disabled.[97] In any case, Honecker spent the majority of January 1990 in hospital after having the error of the tumour missed in 1989 corrected after the suspicion of cancer was confirmed.[98] Upon leaving the hospital on 29 January he was re-arrested and held at the Berlin-Rummelsburg remand centre.[99] However, on the evening of the following day, 30 January, Honecker was again released from custody: The district court had annulled the arrest warrant and, due to medical reports, certified him unfit for detention and interrogation.[100]

Lacking a home, Honecker instructed his lawyer Wolfgang Vogel to ask the Evangelical Church in Berlin-Brandenburg for help. Pastor Uwe Holmer, leader of the Hoffnungstal Institute in Lobetal, Bernau bei Berlin, offered the couple a home in his vicarage.[101] This drew immediate condemnation and later demonstrations against the church for assisting the Honeckers, given they had both discriminated against Christians who did not conform with the SED leadership's ideology.[101][102] Aside from a stay at a holiday home in Lindow in March 1990 that lasted only one day before protests swiftly brought it to an end,[103] the couple resided at the Holmer residence until 3 April 1990.[101]

The couple then moved into a three-room living quarters within the Soviet military hospital in Beelitz.[104] Here, doctors diagnosed a malignant liver tumour following another re-examination. Following German reunification, prosecutors in Berlin issued a further arrest warrant for Honecker in November 1990 on charges that he gave the order to fire on escapees at the Inner German border in 1961 and had repeatedly reiterated that command (most specifically in 1974).[105] However, this warrant was not enforceable because Honecker lay under the protection of Soviet authorities in Beelitz.[106] On 13 March 1991 the Honeckers fled Germany from the Soviet-controlled Sperenberg Airfield to Moscow on a military jet with the aid of Soviet hardliners.[107]

The German Chancellery had only been informed by Soviet diplomats about the Honeckers’ flight to Moscow one hour in advance.[108] It limited its response to a public protest, claiming the existence of an arrest warrant meant the Soviet Union was breaching international law by admitting Honecker.[108] The initial Soviet reaction was that Honecker was now too ill to travel and was receiving medical treatment after a deterioration of his health.[109] He underwent further surgery the following month.[110]

On 11 December 1991 the Honeckers sought refuge in the Chilean Embassy in Moscow, while also applying for political asylum in the Soviet Union.[111] Despite an offer of help from North Korea,[112] Honecker instead reached out to the Chilean government under Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin. Under Honecker's rule, East Germany had granted many Chileans exile following the military coup of 1973 by Augusto Pinochet.[113] In addition his daughter Sonja was married to a Chilean.[114] Chilean authorities, however, stated he could not enter their country without a valid German passport.[115]

Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to the dissolution of the Soviet Union on 25 December 1991 and gave all his powers to Russian president Boris Yeltsin. Russian authorities had long been keen on expelling Honecker,[116] against the wishes of Gorbachev,[117] and the new government now demanded that he leave the country or else face deportation.[118]

In June 1992, Chilean President Patricio Aylwin, leader of a center-left coalition, finally assured German Chancellor Helmut Kohl that Honecker would be leaving the embassy in Moscow.[119] Reportedly against his will,[120] Honecker was ejected from the embassy on 29 July 1992 and flown to Berlin Tegel Airport, where he was arrested and detained in Moabit Prison.[121] By contrast, his wife Margot travelled on a direct flight from Moscow to Santiago, Chile, where she initially stayed with her daughter Sonja.[122] Honecker's lawyers unsuccessfully appealed for him to be released from detention in the period leading up to his trial.[123]

Criminal trial

[edit]

On 12 May 1992, while under protection in the Chilean embassy in Moscow, Honecker, along with several co-defendants, including Erich Mielke, Willi Stoph, Heinz Kessler, Fritz Streletz and Hans Albrecht, were accused in a 783-page indictment of taking part in the "collective manslaughter" of 68 people as they attempted to flee East Germany.[124][125] It was alleged that Honecker, in his role as Chairman of the National Defence Council, had both given the decisive order in 1961 for the construction of the Berlin Wall and also, at subsequent meetings, ordered the extensive expansion of the border fortifications around West Berlin and the barriers to the West so as to make any passing impossible.[125] In addition, specifically at a May 1974 sitting of the National Defence Council, he had stated that the development of the border must continue, that lines of fire were warranted along the whole border and, as prior, the use of firearms was essential: "Comrades who have successfully used their firearms [are] to be praised".[38][125]

The charges were approved by the Berlin District Court on 19 October 1992 at the opening of the trial.[126] On the same day, it was decided that the hearing of 56 charges would be postponed and the remaining twelve cases would be the subject of the trial to begin on 12 November 1992.[126] The question of under which laws the former East German leader could be tried was highly controversial and, in the view of many jurists, the process had an uncertain outcome.[125][127]

During his 70-minute-long statement to the court on 3 December 1992, Honecker said that he had political responsibility for the building of the Berlin Wall and subsequent deaths at the borders, but claimed he was "without juridical, legal or moral guilt".[127] He blamed the escalation of the Cold War for the building of the Berlin Wall, saying the decision had not been taken solely by the East German leadership but all the Warsaw Pact countries that had collectively concluded in 1961 that a "Third World War with millions dead" would be unavoidable without this action.[127] He quoted several West German politicians who had opined that the wall had indeed reduced and stabilised the two factions.[127] He stated that he had always regretted every death, both from a human point of view and due to the political damage they caused.[127]

Making reference to past trials in Germany against communists and socialists such as Karl Marx and August Bebel, he claimed that the legal process against him was politically motivated and a "show trial" against communism.[128][129] He stated that no court lying in the territory of West Germany had the legal right to place him, his co-defendants or any East German citizen on trial, and that the portrayal of East Germany as an "Unrechtsstaat" was contradictory to its recognition by over one hundred other states and the UN Security Council.[130] Furthermore, he questioned how a German court could now legally judge his political decisions in the light of the lack of legal action taken over various military operations that had been carried out by Western countries with either overt support or absence of condemnation from (West) Germany.[130] He dismissed public criticism of the Stasi, arguing that journalists in Western countries were praised for denouncing others.[130] While accepting political responsibility for the deaths at the Wall, he believed he was free of any "legal or moral guilt", and thought that East Germany would go down in history as "a sign that socialism is possible and is better than capitalism".[131]

By the time of the proceedings Honecker was already seriously ill.[132] A new CT scan in August 1992 had confirmed an ultrasound examination made in Moscow and the existence of a malignant tumour in the right lobe of his liver.[133] Based on these findings and additional medical testimonies, Honecker's lawyers requested that the legal proceedings, as far as they were aimed against their client, be abandoned and the arrest warrant against him withdrawn; the cases against both Mielke and Stoph had already been postponed due to their ill health.[132] Arguing that his life expectancy was estimated to be three to six months, while the legal process was forecast to take at least two years, his lawyers questioned whether it was humane to try a dying man.[134] Their application was rejected on 21 December 1992 when the court concluded that, given the seriousness of the charges, no obstacle to the proceedings existed.[135]

Honecker lodged a constitutional complaint to the recently created Constitutional Court of the State of Berlin, stating that the decision to proceed violated his fundamental right to human dignity, which was an overriding principle in the Constitution of Berlin, above even the state penal system and criminal justice.[127][136] On 12 January 1993, Honecker's complaint was upheld and the Berlin District Court therefore abandoned the case and withdrew their arrest warrant.[137] An application for a new arrest warrant was rejected on 13 January. The court also refused to commence with the trial related to the indictment of 12 November 1992, and withdrew the second arrest warrant related to these charges. After a total of 169 days Honecker was released from custody, drawing protests both from victims of the East German regime as well as German political figures.[125][138]

Honecker flew via Brazil to Santiago, Chile, to reunite with his wife and his daughter Sonja, who lived there with her son Roberto. Upon his arrival he was greeted by the leaders of the Chilean Communist and Socialist parties.[139] In contrast, his co-defendants Heinz Kessler, Fritz Streletz and Hans Albrecht were sentenced on 16 September 1993 to imprisonment of between four and seven-and-a-half years.[125] On 13 April 1993 a final attempt to separate and continue the trial against Honecker in his absence was discontinued.[140] Four days later, on the 66th birthday of his wife Margot, he gave a final public speech, ending with the words: "Socialism is the opposite of what we have now in Germany. For that I would like to say that our beautiful memories of the German Democratic Republic are testimony of a new and just society. And we want to always remain loyal to these things".[129]

Death

[edit]Honecker died on 29 May 1994 of liver cancer at the age of 81 in a terraced house in the La Reina district of Santiago. His funeral, arranged by the Communist Party of Chile, was conducted the following day at the central cemetery in Santiago.[141]

Family

[edit]

Honecker was married three times. After being liberated from prison in 1945, he married the prison warden Charlotte Schanuel (née Drost), nine years his senior, on 23 December 1946.[20][29] She died suddenly from a brain tumour in June 1947.[29] Details of this marriage were not revealed until 2003.[20][142]

By the time of her death, Honecker was already romantically involved with the Free German Youth official Edith Baumann,[143] whom he met on a trip to Moscow.[144] With her, he had a daughter.[29][failed verification] Sources differ on whether Honecker and Baumann married in 1947[145] or 1949,[144] but in 1952 he fathered an illegitimate daughter with Margot Feist, a People's Chamber member and chairperson of the Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation.

In September 1950, Baumann wrote directly to Walter Ulbricht to inform him of her husband's extramarital activity in the hope of him pressuring Honecker to end his relationship with Feist.[145] Following his divorce and reportedly under pressure from the Politburo, he married Feist. However, sources again differ on both the year of his divorce from Baumann and of his marriage to Feist; depending on the source, the events took place either in 1953[146] or 1955.[142] For more than twenty years, Margot Honecker served as Minister of National Education. In 2012 intelligence reports collated by West German spies alleged that both Honecker and his wife had secret affairs but did not divorce for political reasons;[147] however, his bodyguard Bernd Brückner, in a book about his time spent in Honecker's service, denied the claims.[148]

Honours and awards

[edit]National honours

[edit] East Germany:

East Germany:

Hero of the German Democratic Republic, twice (1982, 1987)[149]

Hero of the German Democratic Republic, twice (1982, 1987)[149] Hero of Labour (1962)[150]

Hero of Labour (1962)[150] Honor clasp in Gold of the Patriotic Order of Merit (1955)

Honor clasp in Gold of the Patriotic Order of Merit (1955)- Order of Karl Marx, five times (1969, 1972, 1977, 1982, 1985)[151]

Order of the Banner of Labor[151]

Order of the Banner of Labor[151]

Foreign honours

[edit] Austria:

Austria:

People's Republic of Bulgaria:

People's Republic of Bulgaria:

Cuba:

Cuba:

Czechoslovakia:

Czechoslovakia:

First Class of the Order of the White Lion (1987)[151]

First Class of the Order of the White Lion (1987)[151] Order of Klement Gottwald (1982)[155]

Order of Klement Gottwald (1982)[155]

Finland:

Finland:

Polish People's Republic:

Polish People's Republic:

Grand Cordon of the Order of Merit of the People's Republic of Poland

Grand Cordon of the Order of Merit of the People's Republic of Poland

Nicaragua:

Nicaragua:

North Korea:

North Korea:

First Class of the Order of the National Flag (1988)[156]

First Class of the Order of the National Flag (1988)[156]

Socialist Republic of Romania:

Socialist Republic of Romania:

Soviet Union:

Soviet Union:

Hero of the Soviet Union (1982)[151]

Hero of the Soviet Union (1982)[151] Order of Lenin, thrice (1972, 1982, 1987)[151]

Order of Lenin, thrice (1972, 1982, 1987)[151] Order of the October Revolution (1977)[151]

Order of the October Revolution (1977)[151] Medal "For Strengthening of Brotherhood in Arms" (1980)[158]

Medal "For Strengthening of Brotherhood in Arms" (1980)[158] Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1969)

Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1969)- Honorary citizen of the city of Magnitogorsk, Chelyabinsk Oblast (1989)[151]

Vietnam

Vietnam

Gold Star Order (1982)[159]

Gold Star Order (1982)[159]

In popular culture

[edit]

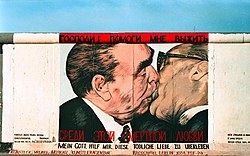

Dmitri Vrubel's 1990 mural on the Berlin Wall My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love, depicting a socialist fraternal kiss between Honecker and Leonid Brezhnev, became known around the world.[161]

A traffic signal inspired by Honecker wearing a jaunty straw hat was used in parts of East Germany (Ost-Ampelmännchen) and has become a symbol of Ostalgie.[162]

British actor Paul Freeman portrayed Honecker in the British-German short film Whispers of Freedom.[163]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Büro Erich Honecker im ZK der SED" (in German). Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Uschner, Manfred (1993). Die zweite Etage: Funktionsweise eines Machtapparates. Zeitthemen (in German). Berlin: Dietz. p. 60. ISBN 978-3-320-01792-7.

- ^ "Honecker, Erich * 25.8.1912, † 29.5.1994 Generalsekretär des ZK der SED, Staatsratsvorsitzender". Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur (in German). Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Erich Honecker 1912–1994". Lebendiges Museum Online (in German). Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Honecker, Margot geb. Feist * 17.4.1927, † 6.5.2016 Ministerin für Volksbildung". Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur (in German). Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Margot Honecker". Chronik der Wende (in German). Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Profile of Erich Honecker

- ^ Connolly, Kate (2 April 2012). "Margot Honecker defends East German dictatorship". The Guardian.

- ^ ""Er hielt sich für den Größten"". Spiegel Politik. More precisely, the term Alleinherrscher (= man who rules alone) is used. 2 August 1992. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Sabrow, Martin (9 February 2012). "Der blasse Diktator. Erich Honecker als biographische Herausforderung" (PDF). Centre for Contemporary History. Here, it is argued Honecker was the biggest despot in recent German history, if you exclude Ludendorff and Hitler. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ The Man Who Built the Berlin Wall: The Rise and Fall of Erich Honecker. Pen and Sword History. 30 September 2023. ISBN 978-1-3990-8885-5.

- ^ a b c Wilsford, David (1995). Political Leaders of Contemporary Western Europe. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 195. ISBN 9780313286230.

- ^ Epstein, Catherine (2003). The Last Revolutionaries: German Communists and their century. Harvard University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780674010451.

- ^ a b c d "Erich Honecker (1912–1994), DDR-Staatsratsvorsitzender". rheinische-geschichte.de (in German). Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Epstein, Catherine (2003). The Last Revolutionaries: German Communists and their century. Harvard University Press. p. 239. ISBN 9780674010451.

- ^ Morina, Christina (2011). Legacies of Stalingrad: Remembering the Eastern Front in Germany since 1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 178.

- ^ "Honecker's Geheimakte lagerte in Mielke's Tresor". Die Welt (in German). 25 August 2012.

- ^ a b c "Immer bereit". Der Spiegel (in German). 3 October 1966. p. 32. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Zum 100. Geburtstag Erich Honeckers" (in German). Unsere Zeit: Zeitung der DKP. 24 August 2012. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "Honeckers geheime Ehen" (in German). Netzeitung.de. 20 January 2003. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Farblos, scheu, wenig kameradschaftlich". Der Spiegel (in German). Hamburg. 31 October 1977. p. 87.

- ^ Przybylski, Peter (1991). Tatort Politbüro: Die Akte Honecker (in German). Rowohlt. pp. 55–65.

- ^ Völklein, Ulrich (2003). Honecker: Eine Biografie (in German). pp. 154–178.

- ^ Paterson, Tony (6 June 2011). "Honecker was forced to resign by secret police". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2017. Martin Sabrow (2016). Erich Honecker. Das Leben davor, C. H. Beck: Munich 2016, p. 376

- ^ a b c Epstein, Catherine (2003). The Last Revolutionaries: German Communists and their century. Harvard University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780674010451.

- ^ Epstein, Catherine (2003). The Last Revolutionaries: German communists and their century. Harvard University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9780674010451.

- ^ Dankiewicz, Jim (1999). The East German Uprising of June 17, 1953 and its Effects on the USSR and the Other Nations of Eastern Europe. University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d Winkler, Heinrich August (2007). Germany: The Long Road West, Vol. 2: 1933–1990. Oxford University Press. pp. 266–268.

- ^ a b c d e "Der unterschätzte Diktator". Der Spiegel (in German). Hamburg. 20 August 2012. p. 46. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Erich Honecker on the 'Unity of Economic and Social Policy' (June 15–19, 1971)". German History in Documents and Images (GHDI). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Allison, Mark (2012). "More from Less: Ideological Gambling with the Unity of Economic and Social Policy in Honecker's GDR". Central European History. 45. Central European History Journal (45): 102–127. doi:10.1017/S0008938911001002. S2CID 155068486.

- ^ Klenke, Olaf (2004). Betriebliche Konflikte in der DDR 1970/71 und der Machtwechsel von Ulbricht auf Honecker (in German).

- ^ "Overview 1971". chronik-der-mauer.de. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Staar, Richard F. (1984). Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe. Hoover Press. p. 105.

- ^ Wehler, Hans-Ulrich (2008). Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Bd. 5: Bundesrepublik und DDR 1949–1950 (in German). p. 218.

- ^ Morley, Nathan (2023). The Man who Built the Berlin Wall. The Rise and Fall of Erich Honecker. Pen and Sword. p. 122.

- ^ Honecker, Erich (1984). "The GDR: A State of Peace and Socialism". Calvin College German Propaganda Archive. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ^ a b "Protokoll der 45. Sitzung des Nationalen Verteidigungsrates der DDR (3 May 1974)" (in German). chronik-der-mauer.de. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Todesopfer an der Berliner Mauer". chronik-der-mauer.de (in German). Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ "Helsinki Final Act signed by 35 participating States". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ Honecker's West German Visit: Divided Meaning, The New York Times, 7 September 1987

- ^ "Honecker begins historic visit to Bonn today". Los Angeles Times. 7 September 1987. Archived from the original on 3 December 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Carr, William (1991). A History of Germany: 1815–1990 (4th ed.). London, United Kingdom: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 392.

- ^ Gedmin, Jeffrey (2003). The Hidden Hand: Gorbachev and the Collapse of East Germany. Harvard University Press. pp. 55–67.

- ^ Treisman, Daniel (2012). The Return: Russia's Journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev. Free Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1416560722.

- ^ "Not all of East Europe is ready for reform". Chicago Tribune. 25 July 1989.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42532-5.

- ^ Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice, Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft (1995). p. 35

- ^ Zelikow and Rice, Germany Unified p. 36.

- ^ "Two Germanys' political divide is being blurred by Glasnost". The New York Times. 18 December 1988. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise and Fall of Communism. Ecco. ISBN 9780061138799.

- ^ "Warsaw Pact warms to Nato plan". Chicago Tribune. 9 July 1989.

- ^ spiegel.de (2009): How Poland and Hungary Led the Way in 1989

- ^ a b "July 1989". chronik-der-mauer.de. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "East German exodus echoes 1961". Chicago Tribune. 22 August 1989. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Der 19. August 1989 war ein Test für Gorbatschows" (German – 19 August 1989 was a test for Gorbachev), in: FAZ 19 August 2009.

- ^ Joachim Riedl: "Ein Brückenleben. Viele Schnurren und eine Sternstunde. Zum Tode Otto von Habsburgs." In: Wochenzeitung Die Zeit, Nr. 28, 7 July 2011, p 11.

- ^ Thomas Roser: DDR-Massenflucht: Ein Picknick hebt die Welt aus den Angeln (German – Mass exodus of the GDR: A picnic clears the world) in: Die Presse 16 August 2018.

- ^ Michael Frank: Paneuropäisches Picknick – Mit dem Picknickkorb in die Freiheit (German: Pan-European picnic – With the picnic basket to freedom), in: Süddeutsche Zeitung 17 May 2010.

- ^ Miklós Németh in Interview, Austrian TV – ORF "Report", 25 June 2019.

- ^ www.chronik-der-mauer.de Archived 3 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine (engl.)

- ^ "Honecker recuperating after gallstone operation". Associated Press. 24 August 1989. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Upheaval in the East; Honecker, in disgrace and in poor health, is arrested as he leaves a Berlin hospital". The New York Times. 30 January 1990.

- ^ Kunze, Thomas (2001). Staatschef: Die letzten Jahre des Erich Honecker (in German). Links. p. 77.

- ^ "Honecker deteriorating". Deseret News. 11 September 1989. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Honecker returns to work after surgery". Los Angeles Times. 26 September 1989.

- ^ "The Opposition charges the SED with fraud in the local elections of May 1989 (May 25, 1989)". German History in Documents and Images.

- ^ De Nevers, Rene (2002). Comrades No More: The Seeds of Political Change in Eastern Europe. MIT Press. p. 173.

- ^ "Hundreds of East Germans reported in Prague Embassy". Associated Press. 21 September 1989. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Refugees crowd West German embassies in East Bloc". Associated Press. 19 September 1989. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021.

- ^ "16,000 refugees flee for freedom East Germany exodus grows". Los Angeles Times. 12 September 1989. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ "East Germans fill refugee camps; New wave from Czechoslovakia". Associated Press. 12 September 1989. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021.

- ^ "East Germany closes its border after 10,000 more flee to West". Chicago Tribune. 4 October 1989.

- ^ "It's not easy being East Germany". Chicago Tribune. 7 October 1989.

- ^ "Gorbachev in East Berlin". BBC News. 25 March 2009.

- ^ a b c "Oct. 7, 1989: How 'Gorbi' spoiled East Germany's 40th Birthday Party". Der Spiegel. 25 March 2009.

- ^ "Gorbachev visit triggered Honecker's ouster, former aid says". Associated Press. 27 December 1989. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "East Germany seeking $371 million Bonn loan". The New York Times. 2 December 1983. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "Goodbye DDR, E04: Erich und die Mauer". ZDF. 20 September 2005. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ "Leadership reaffirms commitment to Communism". Associated Press. 11 October 1989. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Plot to oust East German leader was fraught with risks". Chicago Tribune. 28 October 1990.

- ^ "Erich Honeckers Sturz" (in German). MDR. 5 January 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Die Genossen opfern Honecker – zu spät". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). 17 October 2009.

- ^ a b c "Sekt statt Blut". Der Spiegel (in German). 30 August 1999. p. 60. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "Honecker was forced to resign by secret police". The Independent. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Geheimakte Honecker on YouTube

- ^ "Gorbachev visit triggered Honecker's ouster, former aid says". Associated Press. 27 December 1989. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018.

- ^ "1989: East Germany leader ousted". BBC. 18 October 1989. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Honecker ousted in East Germany, ending 18 years of Iron Rule". Los Angeles Times. 18 October 1989.

- ^ "East Germans oust Honecker". The Guardian. 19 October 1989. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Entire East German leadership resigns". Los Angeles Times. 4 December 1989.

- ^ mdr.de. "Honecker, Erich | MDR.DE". www.mdr.de (in German). Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "East Germany to prosecute ousted rulers". Chicago Tribune. 27 November 1989.

- ^ "Upheaval in the East; Tide of luxuries sweep German leaders away". The New York Times. 10 December 1989.

- ^ "Bürger A 000 000 1". Der Spiegel (in German). 26 February 1990. p. 22.

- ^ "East Germany calls off plans to try Honecker, 3 others". Los Angeles Times. 26 March 1990.

- ^ a b "Honecker released from month-long house arrest". Los Angeles Times. 5 January 1990.

- ^ "Honecker has tumor removed". Los Angeles Times. 10 January 1990. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Honecker jailed on treason charge". Los Angeles Times. 29 January 1990. Archived from the original on 22 February 2025. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Honecker freed; Court says he's too ill for jail". Los Angeles Times. 31 January 1990.

- ^ a b c "Margot und Erich Honecker Asyl im Pfarrhaus gewährt" (in German). Mainpost.de. 4 April 2011. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Der Mann, der Erich Honecker damals Asyl gab" (in German). Hamburger Abendblatt. 30 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010.

- ^ "Ein Sieg Gottes". Berliner Zeitung (in German). 30 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Kunze, Thomas (2001). Staatschef: Die letzten Jahre des Erich Honecker (in German). Links. pp. 106–107.

- ^ "Honecker accused of ordering deaths". Los Angeles Times. 2 December 1990.

- ^ "Honecker's Arrest Sought in Berlin Wall Shootings". The New York Times. 2 December 1990.

- ^ "Soviets may return Honecker to West". Los Angeles Times. 26 August 1991. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Honecker flown to Moscow by Soviets; Bonn protests". Los Angeles Times. 15 March 1991. Archived from the original on 6 December 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Germany demands return of Honecker". Los Angeles Times. 16 March 1991.

- ^ "Moscow military hospital operates on Honecker". Orlando Sentinel. 16 April 1991. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Chilean Embassy in Moscow is giving shelter to Honecker". Los Angeles Times. 13 December 1991. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Moscow's Communist faithful hold rally for Honecker". Los Angeles Times. 17 December 1991. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Chile shelters Honecker because of past favors". The Seattle Times. 12 March 1992. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Ein Leben im Rückwärts". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 18 February 2012. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Chile in quandary over protecting Honecker". The New York Times. 15 January 1990. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "Russia says Honecker will be expelled". Los Angeles Times. 17 November 1991.

- ^ "Russia wants to expel former East German leader". Orlando Sentinel. 17 November 1991. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Soviet disarray; Pyongyang offers Honecker refuge". The New York Times. 15 December 1991. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "Honecker to leave embassy sanctuary in Chile". The Seattle Times. 30 June 1992. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Honecker arraigned on 49 counts". Deseret News. 30 June 1992. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Honecker back in Berlin, may go on trial". Los Angeles Times. 30 July 1992. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Ousted East German leader returned to stand trial". The Baltimore Sun. 30 July 1992. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Court in Berlin refuses to free ailing Honecker". Los Angeles Times. 4 September 1992.

- ^ "Honecker charged in deaths of East Germans in flight". The New York Times. 16 May 1992. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Honecker trial: The East German past and the German future" (PDF). Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies. January 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Honecker trial starts Nov. 12". The New York Times. 21 October 1992.

- ^ a b c d e f Laughland, John (2008). A History of Political Trials: From Charles I to Saddam Hussein. Peter Lang. pp. 195–206.

- ^ Weitz, Eric D. (1996). Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton University Press. p. 3.

- ^ a b "Das Ende der Honecker-Ära" (in German). MDR. 5 January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016.

- ^ a b c "Persönliche Erklärung von Erich Honecker vor dem Berliner Landgericht am 3. Dezember 1992" (in German). Glasnost.de. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Terminally ill Honecker should be released from jail, court rules". The Washington Post. 13 January 1993. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Illness threatens Honecker's trial". The New York Times. 18 November 1992.

- ^ "Doctor says Honecker too sick to stand trial". Chicago Tribune. 17 August 1992.

- ^ "Report sent to court gives Honecker short time to live". The New York Times. 16 December 1992. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "Honecker trial to go forward". The New York Times. 22 December 1992.

- ^ Quint, Peter E. (1997). The Imperfect Union: Constitutional Structures of German Unification. Princeton University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9780691086569.

- ^ "Court ends Honecker trial, citing violation of 'human dignity'". The Baltimore Sun. 13 January 1993. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Honecker release drawing fire in Germany". The New York Times. 24 January 1993. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "Frail Honecker arrives in Santiago". Los Angeles Times. 15 January 1993.

- ^ "Mielke und Honecker: Konspirationsgewohnt". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 7 December 2013.

- ^ "Wo Honecker heimlich begraben wurde". Bild (in German). 25 August 2012. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Honeckers verschwiegene Ehe". Der Spiegel (in German). 20 January 2003. p. 20.

- ^ "Baumann, Edith (verh. Honecker-Baumann) * 1.8.1909, † 7.4.1973 Generalsekretärin der FDJ, Sekretärin des ZK der SED". Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Honeckers Frauen". MDR (in German). 10 February 2011. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Die Stasi-Akte Margot Wie sie sich ihren Erich angelte". Berliner Kurier (in German). 8 May 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Helmut Müller-Enbergs (24 May 2016). "Margot Honecker – Die Frau an seiner Seite". Budeszentrale für politische Bildung (in German). Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ "Secret files: Communist Honecker cheated on wife". The Local. 23 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Erich Honecker: So hielt er es mit Frauen, Familie und Autos". FOCUS Online (in German). 9 May 2014. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Feder, Klaus H.; Feder, Uta (1994). Auszeichnungen der Nationalen Volksarmee der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, 1954-1990 (in German). Munz Galerie.

- ^ Hubrich, Dirk (June 2013). "Verleihungsliste zum Ehrentitel "Held der Arbeit" der DDR von 1950 bis 1989" (PDF). Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ordenskunde e.V. (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Эрих Хонеккер". warheroes.ru. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Feder, Klaus H.; Feder, Uta (2005). Verfreundete Nachbarn: Deutschland - Österreich ; Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, 19. Mai bis 23. Oktober 2005 ; im Zeitgeschichtlichen Forum Leipzig, 2. Juni bis 9. Oktober 2006 ; in Wien 2006 (in German). Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. p. 175. ISBN 9783938025185.

- ^ Chilcote, Ronald H. (1986). Cuba, 1953-1978: A Bibliographic Guide to the Literature. Kraus International Publications. p. 777. ISBN 9780527168247.

- ^ "Speech presenting Playa Girón Order award to Erich Honecker, East Berlin, East Germany". Online Archive of California. 26 October 1986. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Řád Klementa Gottwalda – za budování socialistické vlasti (zřízen vládním nařízením č. 14/1953 Sb. ze dne 3. února 1953, respektive vládním nařízením č. 5/1955 Sb. ze dne 8. února 1955): Seznam nositelů (podle matriky nositelů)

- ^ IDSA News Review on East Asia - Volume 2. 1988. p. 60.

- ^ "Decretul nr. 141/1987 privind conferirea ordinului Victoria Socialismului tovarasului Erich Honecker, secretar general al Comitetului Central al Partidului Socialist Unit din Germania, presedintele Consiliului de Stat al Republicii Democrate Germane". Indaco lege 5 (in Romanian). 25 August 1987. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Эрих Хонеккер". pamyat-naroda.ru. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Văn kiện Quốc hội toàn tập tập VI (quyển 2): 1984–1987". Cổng thông tin điện tử Quốc hội Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 12 December 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ Mackay, Duncan (27 June 2020). "Olympic Order awarded to former East German leader Honecker up for auction". Inside the Games. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Major, Patrick (2009). Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the frontiers of power. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-19-924328-0.

- ^ "East Germany's iconic traffic man turns 50". The Local. 13 October 2013. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Yossman, K.J. (5 March 2024). "Cold War Thriller 'Whispers of Freedom' Sets Principal Cast (EXCLUSIVE) – Global Bulletin". Variety. Archived from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Party Executive Committee until 1950

Further reading

[edit]- Bryson, Phillip J., and Manfred Melzer eds. The End of the East German Economy: From Honecker to Reunification (Palgrave Macmillan, 1991).

- Childs, David, ed. Honecker's Germany (London: Taylor & Francis, 1985).

- Collier Jr, Irwin L. "GDR economic policy during the honecker era." Eastern European Economics 29.1 (1990): 5–29.

- Dennis, Mike. Social and Economic Modernization in Eastern Germany from Honecker to Kohl (Burns & Oates, 1993).

- Dennis, Mike. "The East German Ministry of State Security and East German Society During the Honecker Era, 1971–1989." in German Writers and the Politics of Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 200)3. 3–24 on the STASI

- Fulbrook, Mary. (2008) The People's State: East German Society from Hitler to Honecker. Yale University Press.

- Grix, Jonathan. "Competing approaches to the collapse of the GDR: ‘Top‐down’ vs ‘bottom‐up’," Journal of Area Studies 6#13:121–142, DOI: 10.1080/02613539808455836, Historiography.

- Lippmann, Heinz. Honecker and the New Politics of Europe (New York: Macmillan, 1972).

- McAdams, A. James. "The Honecker trial: The East German past and the German future." Review of Politics 58.1 (1996): 53–80. online

- Morley, Nathan. The Man who Built the Berlin Wall. The Rise and Fall of Erich Honecker. (Pen and Sword, 2023)

- Weitz, Eric D. Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State (Princeton UP, 1997).

- Wilsford, David, ed. Political Leaders of Contemporary Western Europe: A Biographical Dictionary (Greenwood, 1995) pp. 195–201.

Primary sources

[edit]- Honecker, Erich. (1981) From My Life. New York: Pergamon, 1981. ISBN 0-08-024532-3.

External links

[edit]- CNN Cold War – Profile: Erich Honecker at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Honecker im Internet (in German)

- www.warheroes.ru – Erich Honecker (in Russian)

- Welcoming Address to 1979 Session of the World Peace Council Erich Honecker's speech to the WPC

- A Successful Policy Seared to the Needs of the People Volkskammer pamphlet including material by Honecker

Erich Honecker

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Childhood and Family Background

Erich Honecker was born on 25 August 1912 in Neunkirchen, Saarland, to Wilhelm Honecker, a coal miner, and Caroline Catharina Weidenhof.[11][12] The family belonged to the working class in a coal-mining region, living in modest circumstances that reflected the economic realities of the Saar industrial area bordering France.[1][13] Wilhelm Honecker (1881–1969) was politically militant, having joined the Social Democratic Party in 1905 and later engaging in communist activities, which influenced the household.[11] Honecker was the fourth of six children, with older siblings Katharina (1906–1925), Wilhelm (1907–1944), and Frieda (1909–1974), and younger sister Gertrud (born 1917) and brother Karl-Robert (1923–1947).[11][12] Several siblings died prematurely, underscoring the challenges faced by working-class families in early 20th-century Germany.[11] The family home, a plain stucco house on Kuchenberg Street built by Honecker's grandfather—a worker at the local ironworks—exemplified the proletarian environment of Neunkirchen.[14]Education and Initial Political Involvement

Honecker completed his elementary education at the local Volksschule in Neunkirchen, Saarland, around age 14, reflecting the limited formal schooling typical for working-class children in the region during the Weimar era.[1] Unable to secure an apprenticeship immediately after leaving school, he began training as a roofer with his uncle in 1928 but abandoned it unfinished by 1930 to pursue full-time political work, forgoing further vocational or academic development.[15][16] In 1926, at age 14, Honecker joined the Kommunistischer Jugendverband Deutschlands (KJVD), the youth wing of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), marking his entry into organized leftist activism amid economic hardship and political polarization in the Saar coal-mining district.[16] He advanced quickly within the KJVD, becoming a full KPD member in 1929 at age 17, and by 1930 was selected for ideological training at the International Lenin School in Moscow, where he studied Marxist-Leninist theory under Soviet auspices for approximately one year.[16][15] Returning to the Saar in 1931, Honecker was appointed district leader of the KJVD, overseeing agitation, propaganda, and recruitment efforts among youth in the coal-dependent area, which positioned him as a rising functionary in the party's regional apparatus just as Nazi influence grew.[1] This role involved organizing clandestine cells and countering rival youth groups, laying the groundwork for his subsequent underground operations against the emerging Nazi regime.[15]Anti-Nazi Activities and Imprisonment

Communist Youth Work and Opposition

Honecker's involvement in communist youth organizations began in his early adolescence. At age 10 in 1922, he joined a local communist youth group in his hometown of Neunkirchen.[1] By 1926, at age 14, he became a member of the Kommunistische Jugendverband Deutschlands (KJVD), the youth wing of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).[17] [1] In 1928, he assumed leadership of the local KJVD group while apprenticed as a roofer.[17] He formally joined the KPD in 1929 at age 17.[1] In 1930, Honecker attended the International Lenin School in Moscow, a training program for communist cadres, before returning to Germany later that year.[18] [17] Upon his return, he took charge of the KJVD district leadership in the Saar region, focusing on organizing and indoctrinating young workers in Marxist-Leninist principles amid rising economic hardship and political polarization.[1] By 1934, he had advanced to the KJVD's central committee, coordinating youth mobilization efforts across Germany.[17] The Nazi seizure of power in January 1933 and the subsequent ban on the KPD forced Honecker and other communists underground, transforming KJVD activities into clandestine operations.[18] [1] In the Saar, which remained under League of Nations administration until the 1935 plebiscite, he continued semi-open youth organizing until reunification with Germany brought Nazi oversight.[17] Thereafter, operating under a false passport in Berlin from autumn 1935, Honecker led an illegal communist youth network, distributing propaganda, recruiting members, and sabotaging Nazi initiatives through small-scale resistance cells.[17] These efforts aimed to undermine the regime's control over youth via counter-propaganda and fostering anti-fascist solidarity among workers, though constrained by Gestapo surveillance and internal KPD factionalism.[18] His persistent underground coordination of KJVD remnants contributed to his identification as a key agitator.Arrest, Trial, and Sentencing

Honecker was arrested by the Gestapo on December 4, 1935, in Berlin during his clandestine work as a functionary of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which had been driven underground following the Nazi seizure of power in 1933.[19] He had been operating illegally, including forging documents and organizing communist cells among youth, activities that violated Nazi prohibitions on communist organization.[20] Following his detention, Honecker was held in pretrial custody at Berlin's Moabit prison for over a year, during which he endured interrogation by Gestapo officials seeking to extract information on KPD networks.[21] The Nazi regime's Volksgerichtshof (People's Court), established to prosecute political opponents, handled his case as part of broader efforts to dismantle communist resistance, with trials often predetermined to impose severe penalties on ideological enemies.[22] On July 3, 1937, Honecker was convicted of preparing high treason (Hochverrat) and severe falsification of official documents, charges stemming from his role in producing illegal propaganda materials and coordinating subversive activities against the Nazi state.[23] He was sentenced to ten years of hard labor (Zuchthaus), a punishment that reflected the regime's policy of long-term incarceration for communists deemed threats but not immediately warranting execution, unlike some other political prisoners.[19] Honecker refused to recant his communist beliefs during the proceedings, maintaining ideological consistency despite the coercion typical of such show trials.[20]Prison Conditions and Release

Honecker served the majority of his ten-year sentence for preparation of high treason in Brandenburg-Görden Prison, a Zuchthaus facility erected in the late 1920s and repurposed under Nazi rule to detain long-term convicts, including a high proportion of political opponents.[24] The institution housed up to 60% political prisoners by the war's end, subjecting them to overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, chronic malnutrition, and forced labor increasingly tied to armaments production from 1942 onward, such as at the nearby Arado aircraft factory.[24] Treatment varied by racial ideology, with anti-Semitic segregation, sterilizations, and executions targeting "inferior" inmates, while political detainees like communists faced isolation, petty regulations, and heightened disciplinary measures to suppress organization.[24] Despite the regime's brutality—which claimed numerous lives through exhaustion, disease, and direct violence—Honecker's assignment to handyman and glazier tasks afforded him comparatively lighter physical demands than those endured in heavy industrial labor or quarry work.[1] His record of compliance spared him transfer to a concentration camp, a fate met by many fellow communists, allowing him to survive intact and even engage in covert mutual aid networks and self-education in Marxist texts during isolation periods.[25] [1] As Soviet forces approached in April 1945, the prison administration initiated evacuations and death marches for thousands of inmates, but Honecker remained among those liberated on April 27 when Red Army troops captured Brandenburg an der Havel.[24] Over 3,000 prisoners, including Honecker, were released in the ensuing days amid the collapse of Nazi authority, enabling his prompt return to Berlin to affiliate with the Ulbricht Group of Soviet-backed communists.[24] [1]Post-War Rise in the Communist Hierarchy

Reintegration into Soviet-Occupied Germany

Honecker was released from Brandenburg-Görden Prison on 27 April 1945, following its liberation by Soviet Red Army forces advancing through eastern Germany.[26] [24] Physically weakened after nearly eight years of incarceration, including periods of solitary confinement and forced labor, he initially remained in Berlin, which fell within the Soviet sector of the divided city.[27] There, he reconnected with surviving communist networks amid the chaotic transition to Allied occupation, aligning himself with KPD functionaries who had either evaded Nazi persecution or returned from Soviet exile.[15] In the summer of 1945, as the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) resumed operations under Soviet Military Administration oversight in the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ), Honecker was tasked with rebuilding the party's youth wing.[15] This reintegration leveraged his pre-war experience in communist youth organizations, positioning him to organize indoctrination and recruitment efforts among young Germans in the SBZ, where denazification and Soviet-style political restructuring were prioritized.[28] By early 1946, he had assumed leadership of the KPD's youth department in Berlin, directing the formation of the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ), a mass youth organization explicitly modeled on the Soviet Komsomol to foster loyalty to communist ideals and Soviet-aligned governance.[28] [1] The April 1946 forced merger of the KPD and Social Democratic Party (SPD) into the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) further solidified Honecker's role, as the FDJ became the SED's official youth affiliate across the SBZ.[1] His rapid ascent reflected the Soviet authorities' preference for reliable, pre-war communists like Honecker, who demonstrated ideological conformity and organizational skills amid the zone's economic reconstruction and political consolidation, setting the stage for his enduring influence in East German party structures.[15]Leadership in SED Youth Organizations