Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nuclear physics

View on Wikipedia| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the atom as a whole, including its electrons.

Discoveries in nuclear physics have led to applications in many fields such as nuclear power, nuclear weapons, nuclear medicine and magnetic resonance imaging, industrial and agricultural isotopes, ion implantation in materials engineering, and radiocarbon dating in geology and archaeology. Such applications are studied in the field of nuclear engineering.

Particle physics evolved out of nuclear physics and the two fields are typically taught in close association. Nuclear astrophysics, the application of nuclear physics to astrophysics, is crucial in explaining the inner workings of stars and the origin of the chemical elements.

History

[edit]

The history of nuclear physics as a discipline distinct from atomic physics, starts with the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel in 1896,[1] made while investigating phosphorescence in uranium salts.[2] The discovery of the electron by J. J. Thomson[3] a year later was an indication that the atom had internal structure. At the beginning of the 20th century the accepted model of the atom was J. J. Thomson's "plum pudding" model in which the atom was a positively charged ball with smaller negatively charged electrons embedded inside it.

In the years that followed, radioactivity was extensively investigated, notably by Marie Curie, a Polish physicist whose maiden name was Sklodowska, Pierre Curie, Ernest Rutherford and others. By the turn of the century, physicists had also discovered three types of radiation emanating from atoms, which they named alpha, beta, and gamma radiation. Experiments by Otto Hahn in 1911 and by James Chadwick in 1914 discovered that the beta decay spectrum was continuous rather than discrete. That is, electrons were ejected from the atom with a continuous range of energies, rather than the discrete amounts of energy that were observed in gamma and alpha decays. This was a problem for nuclear physics at the time, because it seemed to indicate that energy was not conserved in these decays.

The 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded jointly to Becquerel, for his discovery and to Marie and Pierre Curie for their subsequent research into radioactivity. Rutherford was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1908 for his "investigations into the disintegration of the elements and the chemistry of radioactive substances".

In 1905, Albert Einstein formulated the idea of mass–energy equivalence. While the work on radioactivity by Becquerel and Marie Curie predates this, an explanation of the source of the energy of radioactivity would have to wait for the discovery that the nucleus itself was composed of smaller constituents, the nucleons.

Rutherford discovers the nucleus

[edit]In 1906, Ernest Rutherford published "Retardation of the a Particle from Radium in passing through matter."[4] Hans Geiger expanded on this work in a communication to the Royal Society[5] with experiments he and Rutherford had done, passing alpha particles through air, aluminum foil and gold leaf. More work was published in 1909 by Geiger and Ernest Marsden,[6] and further greatly expanded work was published in 1910 by Geiger.[7] In 1911–1912 Rutherford went before the Royal Society to explain the experiments and propound the new theory of the atomic nucleus as we now understand it.

Published in 1909,[8] with the eventual classical analysis by Rutherford published May 1911,[9][10][11][12] the key preemptive experiment was performed during 1909,[9][13][14][15] at the University of Manchester. Ernest Rutherford's assistant, Professor [15] Johannes [14] "Hans" Geiger, and an undergraduate, Marsden,[15] performed an experiment in which Geiger and Marsden under Rutherford's supervision fired alpha particles (helium 4 nuclei[16]) at a thin film of gold foil. The plum pudding model had predicted that the alpha particles should come out of the foil with their trajectories being at most slightly bent. But Rutherford instructed his team to look for something that shocked him to observe: a few particles were scattered through large angles, even completely backwards in some cases. He likened it to firing a bullet at tissue paper and having it bounce off. The discovery, with Rutherford's analysis of the data in 1911, led to the Rutherford model of the atom, in which the atom had a very small, very dense nucleus containing most of its mass, and consisting of heavy positively charged particles with embedded electrons in order to balance out the charge (since the neutron was unknown). As an example, in this model (which is not the modern one) nitrogen-14 consisted of a nucleus with 14 protons and 7 electrons (21 total particles) and the nucleus was surrounded by 7 more orbiting electrons.

Eddington and stellar nuclear fusion

[edit]Around 1920, Arthur Eddington anticipated the discovery and mechanism of nuclear fusion processes in stars, in his paper The Internal Constitution of the Stars.[17][18] At that time, the source of stellar energy was a complete mystery; Eddington correctly speculated that the source was fusion of hydrogen into helium, liberating enormous energy according to Einstein's equation E = mc2. This was a particularly remarkable development since at that time fusion and thermonuclear energy, and even that stars are largely composed of hydrogen (see metallicity), had not yet been discovered.

Studies of nuclear spin

[edit]The Rutherford model worked quite well until studies of nuclear spin were carried out by Franco Rasetti at the California Institute of Technology in 1929. By 1925 it was known that protons and electrons each had a spin of ±+1⁄2. In the Rutherford model of nitrogen-14, 20 of the total 21 nuclear particles should have paired up to cancel each other's spin, and the final odd particle should have left the nucleus with a net spin of 1⁄2. Rasetti discovered, however, that nitrogen-14 had a spin of 1.

James Chadwick discovers the neutron

[edit]In 1932 Chadwick realized that radiation that had been observed by Walther Bothe, Herbert Becker, Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie was actually due to a neutral particle of about the same mass as the proton, that he called the neutron (following a suggestion from Rutherford about the need for such a particle).[19] In the same year Dmitri Ivanenko suggested that there were no electrons in the nucleus — only protons and neutrons — and that neutrons were spin 1⁄2 particles, which explained the mass not due to protons. The neutron spin immediately solved the problem of the spin of nitrogen-14, as the one unpaired proton and one unpaired neutron in this model each contributed a spin of 1⁄2 in the same direction, giving a final total spin of 1.

With the discovery of the neutron, scientists could at last calculate what fraction of binding energy each nucleus had, by comparing the nuclear mass with that of the protons and neutrons which composed it. Differences between nuclear masses were calculated in this way. When nuclear reactions were measured, these were found to agree with Einstein's calculation of the equivalence of mass and energy to within 1% as of 1934.

Proca's equations of the massive vector boson field

[edit]Alexandru Proca was the first to develop and report the massive vector boson field equations and a theory of the mesonic field of nuclear forces. Proca's equations were known to Wolfgang Pauli[20] who mentioned the equations in his Nobel address, and they were also known to Yukawa, Wentzel, Taketani, Sakata, Kemmer, Heitler, and Fröhlich who appreciated the content of Proca's equations for developing a theory of the atomic nuclei in Nuclear Physics.[21][22][23][24][25]

Yukawa's meson postulated to bind nuclei

[edit]In 1935 Hideki Yukawa[26] proposed the first significant theory of the strong force to explain how the nucleus holds together. In the Yukawa interaction a virtual particle, later called a meson, mediated a force between all nucleons, including protons and neutrons. This force explained why nuclei did not disintegrate under the influence of proton repulsion, and it also gave an explanation of why the attractive strong force had a more limited range than the electromagnetic repulsion between protons. Later, the discovery of the pi meson showed it to have the properties of Yukawa's particle.

With Yukawa's papers, the modern model of the atom was complete. The center of the atom contains a tight ball of neutrons and protons, which is held together by the strong nuclear force, unless it is too large. Unstable nuclei may undergo alpha decay, in which they emit an energetic helium nucleus, or beta decay, in which they eject an electron (or positron). After one of these decays the resultant nucleus may be left in an excited state, and in this case it decays to its ground state by emitting high-energy photons (gamma decay).

The study of the strong and weak nuclear forces (the latter explained by Enrico Fermi via Fermi's interaction in 1934) led physicists to collide nuclei and electrons at ever higher energies. This research became the science of particle physics, the crown jewel of which is the standard model of particle physics, which describes the strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces.

Modern nuclear physics

[edit]A heavy nucleus can contain hundreds of nucleons. This means that with some approximation it can be treated as a classical system, rather than a quantum-mechanical one. In the resulting liquid-drop model,[27] the nucleus has an energy that arises partly from surface tension and partly from electrical repulsion of the protons. The liquid-drop model is able to reproduce many features of nuclei, including the general trend of binding energy with respect to mass number, as well as the phenomenon of nuclear fission.

Superimposed on this classical picture, however, are quantum-mechanical effects, which can be described using the nuclear shell model, developed in large part by Maria Goeppert Mayer[28] and J. Hans D. Jensen.[29] Nuclei with certain "magic" numbers of neutrons and protons are particularly stable, because their shells are filled.

Other more complicated models for the nucleus have also been proposed, such as the interacting boson model, in which pairs of neutrons and protons interact as bosons.

Ab initio methods try to solve the nuclear many-body problem from the ground up, starting from the nucleons and their interactions.[30]

Much of current research in nuclear physics relates to the study of nuclei under extreme conditions such as high spin and excitation energy. Nuclei may also have extreme shapes (similar to that of Rugby balls or even pears) or extreme neutron-to-proton ratios. Experimenters can create such nuclei using artificially induced fusion or nucleon transfer reactions, employing ion beams from an accelerator. Beams with even higher energies can be used to create nuclei at very high temperatures, and there are signs that these experiments have produced a phase transition from normal nuclear matter to a new state, the quark–gluon plasma, in which the quarks mingle with one another, rather than being segregated in triplets as they are in neutrons and protons.

Nuclear decay

[edit]Eighty elements have at least one stable isotope which is never observed to decay, amounting to a total of about 251 stable nuclides. However, thousands of isotopes have been characterized as unstable. These "radioisotopes" decay over time scales ranging from fractions of a second to trillions of years. Plotted on a chart as a function of atomic and neutron numbers, the binding energy of the nuclides forms what is known as the valley of stability. Stable nuclides lie along the bottom of this energy valley, while increasingly unstable nuclides lie up the valley walls, that is, have weaker binding energy.

The most stable nuclei fall within certain ranges or balances of composition of neutrons and protons: too few or too many neutrons (in relation to the number of protons) will cause it to decay. For example, in beta decay, a nitrogen-16 atom (7 protons, 9 neutrons) is converted to an oxygen-16 atom (8 protons, 8 neutrons)[31] within a few seconds of being created. In this decay a neutron in the nitrogen nucleus is converted by the weak interaction into a proton, an electron and an antineutrino. The element is transmuted to another element, with a different number of protons.

In alpha decay, which typically occurs in the heaviest nuclei, the radioactive element decays by emitting a helium nucleus (2 protons and 2 neutrons), giving another element, plus helium-4. In many cases this process continues through several steps of this kind, including other types of decays (usually beta decay) until a stable element is formed.

In gamma decay, a nucleus decays from an excited state into a lower energy state, by emitting a gamma ray. The element is not changed to another element in the process (no nuclear transmutation is involved).

Other more exotic decays are possible (see the first main article). For example, in internal conversion decay, the energy from an excited nucleus may eject one of the inner orbital electrons from the atom, in a process which produces high speed electrons but is not beta decay and (unlike beta decay) does not transmute one element to another.

Nuclear fusion

[edit]In nuclear fusion, two low-mass nuclei come into very close contact with each other so that the strong force fuses them. It requires a large amount of energy for the strong or nuclear forces to overcome the electrical repulsion between the nuclei in order to fuse them; therefore nuclear fusion can only take place at very high temperatures or high pressures. When nuclei fuse, a very large amount of energy is released and the combined nucleus assumes a lower energy level. The binding energy per nucleon increases with mass number up to nickel-62. Stars like the Sun are powered by the fusion of four protons into a helium nucleus, two positrons, and two neutrinos. The uncontrolled fusion of hydrogen into helium is known as thermonuclear runaway. A frontier in current research at various institutions, for example the Joint European Torus (JET) and ITER, is the development of an economically viable method of using energy from a controlled fusion reaction. Nuclear fusion is the origin of the energy (including in the form of light and other electromagnetic radiation) produced by the core of all stars including our own Sun.

Nuclear fission

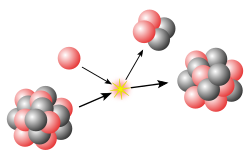

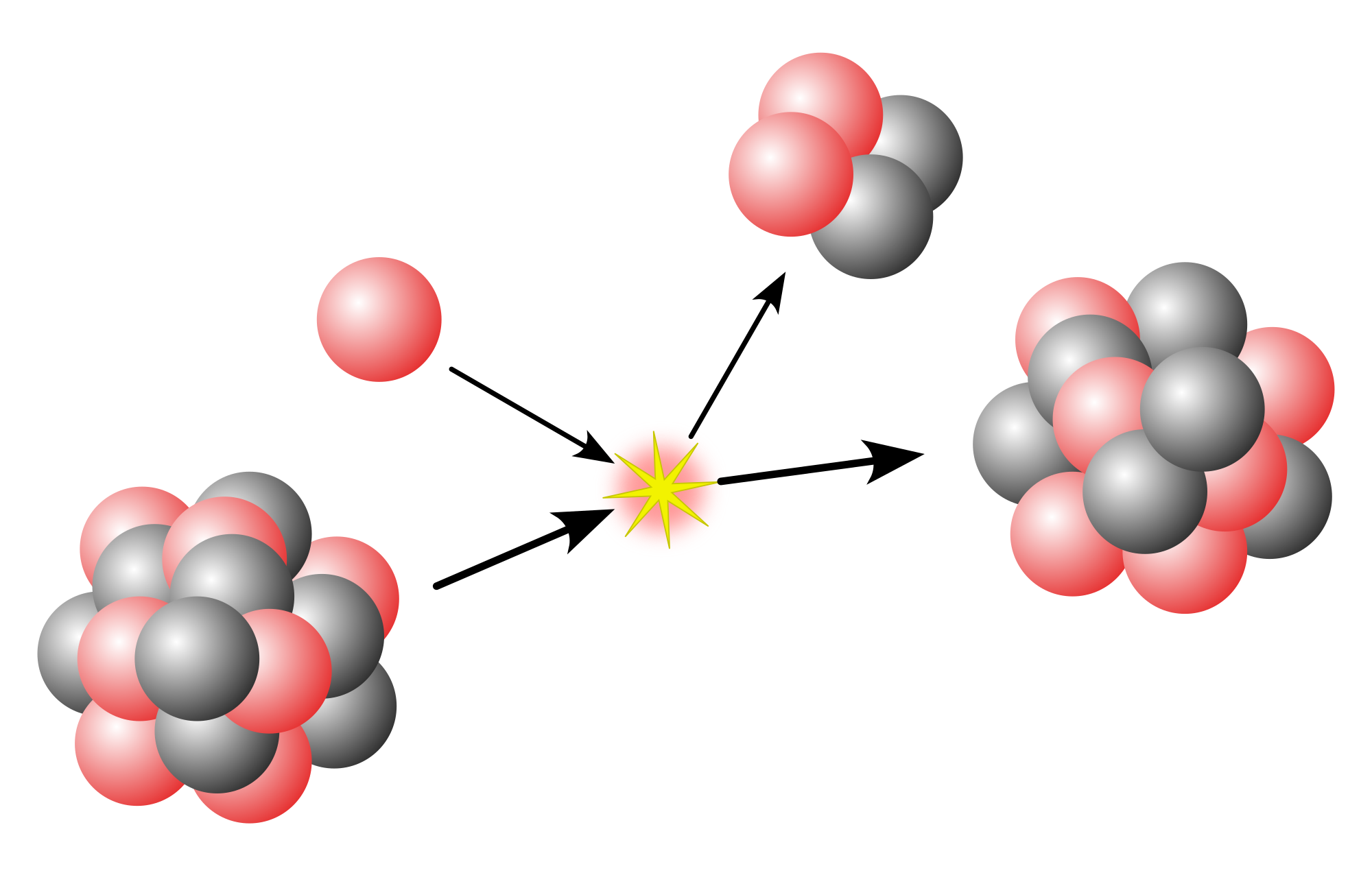

[edit]Nuclear fission is the reverse process to fusion. For nuclei heavier than nickel-62 the binding energy per nucleon decreases with the mass number. It is therefore possible for energy to be released if a heavy nucleus breaks apart into two lighter ones.

The process of alpha decay is in essence a special type of spontaneous nuclear fission. It is a highly asymmetrical fission because the four particles which make up the alpha particle are especially tightly bound to each other, making production of this nucleus in fission particularly likely.

From several of the heaviest nuclei whose fission produces free neutrons, and which also easily absorb neutrons to initiate fission, a self-igniting type of neutron-initiated fission can be obtained, in a chain reaction. Chain reactions were known in chemistry before physics, and in fact many familiar processes like fires and chemical explosions are chemical chain reactions. The fission or "nuclear" chain-reaction, using fission-produced neutrons, is the source of energy for nuclear power plants and fission-type nuclear bombs, such as those detonated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, at the end of World War II. Heavy nuclei such as uranium and thorium may also undergo spontaneous fission, but they are much more likely to undergo decay by alpha decay.

For a neutron-initiated chain reaction to occur, there must be a critical mass of the relevant isotope present in a certain space under certain conditions. The conditions for the smallest critical mass require the conservation of the emitted neutrons and also their slowing or moderation so that there is a greater cross-section or probability of them initiating another fission. In two regions of Oklo, Gabon, Africa, natural nuclear fission reactors were active over 1.5 billion years ago.[32] Measurements of natural neutrino emission have demonstrated that around half of the heat emanating from the Earth's core results from radioactive decay. However, it is not known if any of this results from fission chain reactions.[33]

Production of "heavy" elements

[edit]According to the theory, as the Universe cooled after the Big Bang it eventually became possible for common subatomic particles as we know them (neutrons, protons and electrons) to exist. The most common particles created in the Big Bang which are still easily observable to us today were protons and electrons (in equal numbers). The protons would eventually form hydrogen atoms. Almost all the neutrons created in the Big Bang were absorbed into helium-4 in the first three minutes after the Big Bang, and this helium accounts for most of the helium in the universe today (see Big Bang nucleosynthesis).

Some relatively small quantities of elements beyond helium (lithium, beryllium, and perhaps some boron) were created in the Big Bang, as the protons and neutrons collided with each other, but all of the "heavier elements" (carbon, element number 6, and elements of greater atomic number) that we see today, were created inside stars during a series of fusion stages, such as the proton–proton chain, the CNO cycle and the triple-alpha process. Progressively heavier elements are created during the evolution of a star.

Energy is only released in fusion processes involving smaller atoms than iron because the binding energy per nucleon peaks around iron (56 nucleons). Since the creation of heavier nuclei by fusion requires energy, nature resorts to the process of neutron capture. Neutrons (due to their lack of charge) are readily absorbed by a nucleus. The heavy elements are created by either a slow neutron capture process (the so-called s-process) or the rapid, or r-process. The s process occurs in thermally pulsing stars (called AGB, or asymptotic giant branch stars) and takes hundreds to thousands of years to reach the heaviest elements of lead and bismuth. The r-process is thought to occur in supernova explosions, which provide the necessary conditions of high temperature, high neutron flux and ejected matter. These stellar conditions make the successive neutron captures very fast, involving very neutron-rich species which then beta-decay to heavier elements, especially at the so-called waiting points that correspond to more stable nuclides with closed neutron shells (magic numbers).

See also

[edit]- Isomeric shift

- Neutron-degenerate matter

- Nuclear chemistry

- Nuclear matter

- Nuclear model

- Nuclear spectroscopy

- Nuclear structure

- Nucleonica, web driven nuclear science portal

- QCD matter

References

[edit]- ^ B. R. Martin (2006). Nuclear and Particle Physics. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-470-01999-3.

- ^ Henri Becquerel (1896). "Sur les radiations émises par phosphorescence". Comptes Rendus. 122: 420–421. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2010-09-21.

- ^ Thomson, Joseph John (1897). "Cathode Rays". Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain. XV: 419–432.

- ^ Rutherford, Ernest (1906). "On the retardation of the α particle from radium in passing through matter". Philosophical Magazine. 12 (68): 134–146. doi:10.1080/14786440609463525. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2019-07-01.

- ^ Geiger, Hans (1908). "On the scattering of α-particles by matter". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 81 (546): 174–177. Bibcode:1908RSPSA..81..174G. doi:10.1098/rspa.1908.0067.

- ^ Geiger, Hans; Marsden, Ernest (1909). "On the diffuse reflection of the α-particles". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 82 (557): 495. Bibcode:1909RSPSA..82..495G. doi:10.1098/rspa.1909.0054.

- ^ Geiger, Hans (1910). "The scattering of the α-particles by matter". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 83 (565): 492–504. Bibcode:1910RSPSA..83..492G. doi:10.1098/rspa.1910.0038.

- ^ H. Geiger and E. Marsden, PM, 25, 604 1913, citing, H. Geiger and E. Marsden, Roy. Soc. Proc. vol. LXXXII. p. 495 (1909), in, The Laws of Deflexion of α Particles Through Large Angles \\ H. Geiger and E. Marsden Archived 2019-05-01 at the Wayback Machine (1913), (published subsequently online by – physics.utah.edu (University of Utah)) Retrieved June 13, 2021 (p.1):"..In an earlier paper, however, we pointed out that α particles are sometimes turned through very large angles..."(p.2):"..Professor Rutherford has recently developed a theory to account for the scattering of α particles through these large angles, the assumption being that the deflexions are the result of an intimate encounter of an α particle with a single atom of the matter traversed. In this theory an atom is supposed to consist of a strong positive or negative central charge concentrated within a sphere of less than about 3 × 10–12 cm. radius, and surrounded by electricity of the opposite sigh distributed throughout the remainder of the atom of about 10−8 cm. radius..."

- ^ a b Radvanyi, Pierre (January–February 2011). "Physics and Radioactivity after the Discovery of Polonium and Radium" (electronic). Chemistry International. 33 (1). online: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

..Geiger and an English-New Zealand student, E. Marsden, to study their scattering through thin metallic foils. In 1909, the two physicists observe that some alpha-particles are scattered backwards by thin platinum or gold foils (Geiger 1909)...It takes Rutherford one and a half years to understand this result. In 1911, he concludes that the atom contains a very small 'nucleus'...

- ^ Rutherford F.R.S., E. (May 1911). "The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom". Philosophical Magazine. 6. 21 May 1911: 669–688. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Rutherford, E. (May 1911). "LXXIX. The scattering of α and β particles by matter and the structure of the atom". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 21 (125): 669–688. doi:10.1080/14786440508637080.

- ^ "1911 John Ratcliffe and Ernest Rutherford (smoking) at the Cavendish Laboratory..." Fermilab. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021."..that would become a classic technique of particle physics..."

- ^ *Davidson, Michael W. "The Rutherford Experiment". micro.magnet. micro.magnet.fsu.edu. Florida State: Florida State University. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021. "experiment was conducted 1911"

- "CULTURE AND HISTORY FEATURE Rutherford, transmutation and the proton 8 May 2019 The events leading to Ernest Rutherford's discovery of the proton, published in 1919". CERN Courier. IOP Publishing. 8 May 2019. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021."...1909...a couple of years later..."

- "This Month in Physics History: May, 1911: Rutherford and the Discovery of the Atomic Nucleus". APS News. 15 (5). May 2006. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021."..1909..published – 1911.."

- Anderson, Ashley. "Timeline". University of Alaska-Fairbanks. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021. "1911 performed "

- 1911 discovers:

- Leonard, P. and Gehrels, N. (November 28, 2009) A History of Gamma-Ray Astronomy Including Related Discoveries Archived 2021-06-13 at the Wayback Machine National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center: High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center (HEASARC), Retrieved 13 June 2021

- Rizvi, Eram – Quantum Mechanics and Particle Scattering Lecture 1 Archived 2021-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, p.9, pprc.qmul.ac.uk Queen Mary University London: School of Physics and Astronomy – Particle Physics Research Centre, Retrieved 13 June 2021 "..by Rutherford.."

- rutherford/biographical Archived 2023-06-03 at the Wayback Machine, Nobel Prize, "..In 1910, his investigations into the scattering of alpha rays and the nature of the inner structure of the atom which caused such scattering led to the postulation of his concept of the 'nucleus'..."

- "Case studies from the history of physics". Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

..It is suggested that, in 1910, the 'plum pudding model' was suddenly overturned by Rutherford's experiment. In fact, Rutherford had already formulated the nuclear model of the atom before the experiment was carried out..

- ^ a b Jariskog, Cecilia (December 2008). "ANNIVERSARY The nucleus and more" (PDF). CERN Courrier. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

.. in 1911, Rutherford writes: "I have been working recently on scattering of alpha and beta particles and have devised a new atom to explain the results..

- ^ a b c Godenko, Lyudmila. The Making of the Atomic Bomb (E-Book). cuny.manifoldapp.org CUNY's Manifold (City University of New York). Retrieved 13 June 2021.

The discovery for which Rutherford is most famous is that atoms have nuclei; ...had its beginnings in 1909...Geiger and Marsden published their anomalous result in July, 1909...The first public announcement of this new model of atomic structure seems to have been made on March 7, 1911, when Rutherford addressed the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society;...

[permanent dead link] - ^ Watkins, Thayer. "The Structure and Binding Energy of the Alpha Particle, the Helium 4 Nucleus". San Jose University. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Eddington, A. S. (1920). "The Internal Constitution of the Stars". The Scientific Monthly. 11 (4): 297–303. Bibcode:1920SciMo..11..297E. JSTOR 6491.

- ^ Eddington, A. S. (1916). "On the radiative equilibrium of the stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77: 16–35. Bibcode:1916MNRAS..77...16E. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.1.16.

- ^ Chadwick, James (1932). "The existence of a neutron". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 136 (830): 692–708. Bibcode:1932RSPSA.136..692C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1932.0112.

- ^ W. Pauli, Nobel lecture, December 13, 1946.

- ^ Poenaru, Dorin N.; Calboreanu, Alexandru (2006). "Alexandru Proca (1897–1955) and his equation of the massive vector boson field". Europhysics News. 37 (5): 25–27. Bibcode:2006ENews..37e..24P. doi:10.1051/epn:2006504. S2CID 123558823.

- ^ G. A. Proca, Alexandre Proca.Oeuvre Scientifique Publiée, S.I.A.G., Rome, 1988.

- ^ Vuille, C.; Ipser, J.; Gallagher, J. (2002). "Einstein–Proca model, micro black holes, and naked singularities". General Relativity and Gravitation. 34 (5): 689. arXiv:1406.0497. Bibcode:2002GReGr..34..689V. doi:10.1023/a:1015942229041. S2CID 118221997.

- ^ Scipioni, R. (1999). "Isomorphism between non-Riemannian gravity and Einstein–Proca–Weyl theories extended to a class of scalar gravity theories". Class. Quantum Gravity. 16 (7): 2471–2478. arXiv:gr-qc/9905022. Bibcode:1999CQGra..16.2471S. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/16/7/320. S2CID 6740644.

- ^ Tucker, R. W; Wang, C (1997). "An Einstein–Proca-fluid model for dark matter gravitational interactions". Nuclear Physics B: Proceedings Supplements. 57 (1–3): 259–262. Bibcode:1997NuPhS..57..259T. doi:10.1016/s0920-5632(97)00399-x.

- ^ Yukawa, Hideki (1935). "On the Interaction of Elementary Particles. I". Proceedings of the Physico-Mathematical Society of Japan. 3rd Series. 17: 48–57. doi:10.11429/ppmsj1919.17.0_48. Archived from the original on Nov 22, 2023.

- ^ J.M.Blatt and V.F.Weisskopf, Theoretical Nuclear Physics, Springer, 1979, VII.5

- ^ Mayer, Maria Goeppert (1949). "On Closed Shells in Nuclei. II". Physical Review. 75 (12): 1969–1970. Bibcode:1949PhRv...75.1969M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.75.1969.

- ^ Haxel, Otto; Jensen, J. Hans D; Suess, Hans E (1949). "On the "Magic Numbers" in Nuclear Structure". Physical Review. 75 (11): 1766. Bibcode:1949PhRv...75R1766H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.75.1766.2.

- ^ Stephenson, C.; et., al. (2017). "Topological properties of a self-assembled electrical network via ab initio calculation". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 932. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7..932B. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01007-9. PMC 5430567. PMID 28428625.

- ^ Not a typical example as it results in a "doubly magic" nucleus

- ^ Meshik, A. P. (November 2005). "The Workings of an Ancient Nuclear Reactor". Scientific American. 293 (5): 82–91. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293e..82M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1105-82. PMID 16318030. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ^ Biello, David (July 18, 2011). "Nuclear Fission Confirmed as Source of More than Half of Earth's Heat". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]Introductory

[edit]- Semat, H. and Albright, John R. (1972). Introduction to Atomic and Nuclear Physics. Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-15670-0.

- Littlefield, T.A. and Thorley, N. (1979) Atomic and Nuclear Physics: An Introduction. Springer US. ISBN 978-0-442-30190-3.

- Belyaev, Alexander; Ross, Douglas (2021). The Basics of Nuclear and Particle Physics. Undergraduate Texts in Physics. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Bibcode:2021bnpp.book.....B. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-80116-8. ISBN 978-3-030-80115-1. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- Povh, Bogdan; Rith, Klaus; Scholz, Christoph; Zetsche, Frank; Rodejohann, Werner (2015). Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts. Graduate Texts in Physics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-46321-5. ISBN 978-3-662-46320-8. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

Reference works

[edit]- Handbook of Nuclear Physics. Isao Tanihata, Hiroshi Toki, Toshitaka Kajino (eds.). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. 2020. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-8818-1. ISBN 9789811588181. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Advanced

[edit]- Cohen, Bernard L, (1971). Concepts of Nuclear Physics, McGraw-Hill, Inc.

- Bohr, Aage; Mottelson, Ben R (1998) [1969]. Nuclear Structure: (In 2 Volumes). World Scientific. doi:10.1142/3530. ISBN 978-981-02-3197-2. Archived from the original on 2023-01-20. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- Greiner, Walter; Maruhn, Joachim A. and Bromley, D.A (1996) Nuclear Models. Springer ISBN 9783540591801. * Paetz gen. Schieck, Hans (2014). Nuclear Reactions: An Introduction. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 882. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-53986-2. ISBN 978-3-642-53985-5. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

Classics or Historic

[edit]- Fermi, E. (1950). Nuclear Physics. Univ. Chicago Press

- Mott, N. F.; Massey, H. S. W. (1949). The Theory Of Atomic Collisions. The International Series of Monographs on Physics (2. ed.). Oxford: Calrendon Press (OUP).

- Blatt, John M.; Weisskopf, Victor F. (1979) [1952]. Theoretical Nuclear Physics. New York, NY: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-9959-2. ISBN 978-1-4612-9961-5. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- Bethe, Hans A.; Morrison, Philip (2006) [1956]. Elementary Nuclear Theory. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-45048-3.

External links

[edit]- Ernest Rutherford's biography at the American Institute of Physics Archived 2016-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- American Physical Society Division of Nuclear Physics Archived 2017-09-20 at the Wayback Machine

- American Nuclear Society Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Annotated bibliography on nuclear physics from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Nuclear science wiki Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Nuclear Data Services – IAEA Archived 2021-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Nuclear Physics , BBC Radio 4 discussion with Jim Al-Khalili, John Gribbin and Catherine Sutton (In Our Time, Jan. 10, 2002)

Nuclear physics

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Early Radioactivity and Nucleus Discovery (1896–1920s)

In February 1896, Henri Becquerel observed that uranium salts emitted rays capable of penetrating black paper and exposing a photographic plate, initially hypothesizing a connection to phosphorescence excited by sunlight.[11] Further experiments on March 1, 1896, confirmed the emission occurred spontaneously without external stimulation, marking the discovery of radioactivity as an inherent atomic property.[12] Becquerel's findings demonstrated that uranium emitted penetrating radiation continuously, independent of temperature or chemical form, with intensity proportional to uranium content.[13] Building on Becquerel's work, Pierre and Marie Curie systematically investigated pitchblende ore, which exhibited higher radioactivity than its uranium content suggested. In July 1898, they announced the discovery of polonium, an element 400 times more active than uranium, named after Marie's native Poland.[14] By December 1898, they identified radium, approximately two million times more radioactive than uranium, through laborious chemical separations yielding milligram quantities from tons of ore.[15] These isolations established radioactivity as an atomic phenomenon tied to specific elements, prompting the term "radioactive elements" for substances decaying via emission.[14] Ernest Rutherford, collaborating with Frederick Soddy, classified radioactive emissions into three types between 1899 and 1903. Alpha rays, deflected by electric and magnetic fields toward the negative plate but less than beta rays, were identified as doubly ionized helium atoms (He²⁺) with mass about 4 amu and charge +2e.[16] Beta rays behaved as negatively charged particles with mass near that of electrons (cathode ray particles discovered by J.J. Thomson in 1897), penetrating farther than alphas.[17] Gamma rays, discovered in 1900 from radium decay, showed no deflection in fields, indicating neutral, high-energy electromagnetic radiation akin to X-rays but more penetrating.[16] Rutherford and Soddy's studies revealed sequential decay chains, with alpha emission transmuting elements by reducing atomic number by 2 and mass by 4, explaining observed half-lives and new species formation.[18] J.J. Thomson's 1904 plum pudding model described the atom as a uniform sphere of positive charge, roughly 10⁻¹⁰ m in diameter, with electrons embedded like plums to maintain neutrality, consistent with observed atomic masses and electron counts. This diffuse structure accounted for minimal scattering in early experiments but predicted uniform deflection for charged probes.[19] In 1909–1911, Rutherford, with Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, directed alpha particles from radium at thin gold foil (about 10⁻⁷ m thick). Contrary to Thomson's model, most particles passed undeflected, but approximately 1 in 8000 scattered by over 90 degrees, and some backscattered, implying atoms contain a minuscule, dense core (radius <10⁻¹⁴ m) bearing positive charge and most mass.[20] Rutherford's 1911 analysis, using hyperbolic trajectories under Coulomb scattering, estimated the nucleus radius as 10,000 times smaller than the atom's, with charge Ze where Z is atomic number.[21] This nuclear model supplanted the plum pudding view, positing electrons orbiting a central nucleus, laying groundwork for later quantum refinements by 1920.[20]Neutron Identification and Pre-Fission Era (1930–1938)

In 1930, German physicists Walther Bothe and Herbert Becker bombarded beryllium nuclei with alpha particles from polonium, observing a highly penetrating neutral radiation that produced coincidence counts with secondary particles but resisted absorption by materials that stopped charged particles or typical gamma rays; they interpreted this as gamma radiation of unprecedented energy exceeding 10 MeV.[22] In 1932, French physicists Irène and Frédéric Joliot replicated and extended these results, noting that the radiation ejected protons from paraffin wax with kinetic energies up to approximately 5 MeV, which implied incident gamma photons of around 50 MeV to satisfy Compton scattering kinematics—a value far beyond contemporary theoretical limits for nuclear gamma emission.[23] James Chadwick, working at the Cavendish Laboratory under Ernest Rutherford, investigated these findings in early 1932 by directing the beryllium-alpha radiation onto paraffin and measuring recoil proton energies via ionization in air; the maximum proton energy of 5.7 MeV could not be reconciled with high-energy gamma rays under Compton or photoelectric effects, as it required impossible photon momenta without violating conservation laws.[24] Chadwick proposed instead a neutral particle with mass comparable to the proton (approximately 1 atomic mass unit), dubbing it the "neutron" for its lack of charge and role in ejecting protons via elastic collisions; momentum and energy conservation fit precisely with this hypothesis, and subsequent scattering experiments on nitrogen and other gases confirmed the neutron's neutrality and mass.[22] Chadwick announced the discovery in a letter to Nature on February 27, 1932, followed by a detailed paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, resolving anomalies in isotopic masses and nuclear binding while earning him the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics. The neutron's identification enabled rapid advances in nuclear transmutations. In December 1931, Harold Urey isolated deuterium (heavy hydrogen isotope-2) via fractional distillation and electrolysis, its mass-2 nucleus interpreted by Rutherford as a proton bound to a neutron, providing early empirical support for composite nuclei beyond protons alone.[25] In April 1932, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton at Cavendish used a high-voltage electrostatic accelerator to propel protons at 700 keV onto lithium-7 targets, detecting alpha particles with 8 MeV energy via scintillation screens, confirming the endothermic reaction and demonstrating artificial nuclear disintegration with energy release as predicted by Weizsäcker's semi-empirical mass formula— the first such feat without relying on natural radioactive sources.[26] These proton-lithium collisions released neutrons, further validating Chadwick's particle in reaction products.[27] By 1934, neutron applications expanded nuclear synthesis. Irène and Frédéric Joliot induced artificial radioactivity by bombarding boron-10 with polonium alphas, yielding unstable nitrogen-13 (half-life 10 minutes) that decayed via positron emission to carbon-13 plus a neutrino, as , followed by ; similar positrons arose from aluminum and magnesium transmutations, marking the first human-created radioisotopes and earning the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[28] Enrico Fermi's group in Rome, using radium-beryllium neutron sources, systematically irradiated elements from hydrogen to uranium, inducing radioactivity in over 60 species and classifying activities by half-life; crucially, in October 1934, they found that neutrons slowed by elastic scattering in paraffin or water (thermalizing to ~0.025 eV) exhibited cross-sections for capture up to 100–1000 times higher than fast neutrons (~1 MeV), enhancing reaction probabilities via lowered centrifugal barriers in s-wave interactions.[29] These slow-neutron effects underpinned Fermi's 1934–1937 investigations into heavy-element transmutations, where uranium bombarded with moderated neutrons produced new beta-emitters (e.g., 13-second, 2.3-minute, 40-second activities), initially ascribed to transuranic elements beyond neptunium rather than fission fragments, as isotopic assignments favored sequential neutron capture and beta decay over symmetric splitting.[30] Complementary theoretical progress included Hideki Yukawa's 1935 meson-exchange model for the strong nuclear force mediating proton-neutron binding, positing a massive particle (~200 proton masses) to confine the short-range force within ~10^{-15} m, anticipating pion discovery.[31] By 1938, refined neutron spectroscopy and cross-section measurements, often via cloud chambers tracking recoil ions, solidified the neutron as the glue resolving nuclear stability puzzles, setting the stage for fission's elucidation without yet revealing chain-reaction potential.[32]Fission Discovery and World War II Mobilization (1938–1945)

In late 1938, German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann bombarded uranium atoms with neutrons and detected lighter elements, including barium, which indicated the nucleus had split into fragments rather than merely transmuting.[33] Lise Meitner, who had collaborated with Hahn but fled Nazi Germany due to her Jewish ancestry, and her nephew Otto Frisch provided the theoretical interpretation during a walk in Sweden over Christmas 1938, calculating that the process released approximately 200 million electron volts per fission event and proposing it resembled biological fission, a term Frisch formalized as "nuclear fission" in early 1939.[34] Their explanation, published in Nature on February 11, 1939, highlighted the potential for a self-sustaining chain reaction if neutrons from fission could induce further splits, releasing vast energy from uranium-235.[35] The discovery rapidly alarmed émigré physicists fearing Nazi weaponization, as Germany's Uranverein program had begun exploring uranium in April 1939.[36] Leo Szilard, recognizing the military implications, drafted a letter signed by Albert Einstein on August 2, 1939, warning President Franklin D. Roosevelt that German scientists might achieve chain reactions in a large uranium mass, producing bombs of "unimaginable power," and urging U.S. government funding for uranium research and isotope separation.[37] Delivered on October 11, 1939, amid war's outbreak, it prompted Roosevelt to form the Advisory Committee on Uranium, initially allocating $6,000 for fission studies at universities like Columbia, where Enrico Fermi demonstrated uranium-graphite chain reaction hints by 1940.[38] By mid-1941, British MAUD Committee reports confirmed a uranium bomb's feasibility with 10-25 pounds of U-235, accelerating U.S. efforts despite skepticism over scale.[39] In June 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers assumed control under Brigadier General Leslie Groves, rebranding as the Manhattan Engineer District with a $2 billion budget (equivalent to about $30 billion in 2023 dollars), employing 130,000 personnel across sites including Oak Ridge, Tennessee, for electromagnetic and gaseous diffusion uranium enrichment; Hanford, Washington, for plutonium production via reactors; and Los Alamos, New Mexico, laboratory directed by J. Robert Oppenheimer for bomb design.[40] Fermi's team achieved the first controlled chain reaction on December 2, 1942, in Chicago Pile-1, a 40-foot graphite-moderated uranium pile under the University of Chicago's Stagg Field, sustaining neutron multiplication for 28 minutes and validating reactor scalability.[41] Parallel advances addressed fissile material scarcity: Oak Ridge's calutrons produced sufficient U-235 by 1945, while Hanford's B Reactor yielded plutonium-239, though its spontaneous fission necessitated an implosion lens design over simpler gun-type assembly.[39] Oppenheimer's team, including physicists like Richard Feynman and Edward Teller, overcame implosion symmetry challenges through hydrodynamical modeling and high-explosive tests. The Trinity test on July 16, 1945, detonated a 21-kiloton plutonium device at Alamogordo, New Mexico, confirming viability with a yield from rapid supercritical assembly, though initial fears of atmospheric ignition proved unfounded via prior calculations.[42] This culminated in Little Boy (uranium gun-type, 15 kilotons) dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and Fat Man (plutonium implosion, 21 kilotons) on Nagasaki on August 9, ending organized Japanese resistance by August 15.[39] Allied intelligence verified Germany's program stalled early due to resource diversion and misprioritization, never nearing a bomb.[40]Post-War Expansion and Cold War Accelerators (1946–1980s)

Following World War II, nuclear physics research expanded significantly under substantial government patronage, particularly in the United States, where the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 established the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to oversee atomic energy development, including fundamental research into nuclear structure and reactions.[43] The AEC allocated millions in funding annually to national laboratories and universities, recognizing nuclear physics' dual role in weapons advancement and basic science, with nuclear physics emerging as the primary beneficiary of federal support amid Cold War priorities.[44] This era saw the founding of facilities like Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1947, initially focused on civilian nuclear applications but quickly incorporating accelerator-based experiments to probe nuclear forces and isotopic properties.[45] Internationally, similar expansions occurred, though constrained by geopolitical tensions, with Soviet facilities emphasizing parallel accelerator developments for nuclear studies. Accelerator technology advanced rapidly to achieve higher energies needed for detailed nuclear investigations, building on wartime innovations. The 184-inch synchrocyclotron at the University of California, Berkeley, achieved first operation in November 1946, modulating frequency to compensate for relativistic effects and accelerating deuterons to 190 MeV or alpha particles to 380 MeV, which enabled pioneering scattering experiments revealing nuclear potential shapes and reaction mechanisms.[46] Shortly thereafter, Brookhaven's Cosmotron, a weak-focusing proton synchrotron with a 75-foot diameter and 2,000-ton magnet array, reached 3 GeV in 1952—the world's first GeV-scale machine—facilitating nuclear emulsion studies and pion production for meson-nuclear interactions.[45] These instruments shifted research from low-energy spectroscopy to high-energy collisions, yielding data on nuclear excitation and fission barriers under extreme conditions. The 1950s and 1960s brought even larger synchrotrons tailored for nuclear physics, exemplified by Berkeley's Bevatron, operational from 1954 and designed to deliver 6.2 GeV protons, which supported heavy-ion beam lines and experiments on hypernuclei formation and nuclear matter compressibility.[47] Heavy-ion accelerators proliferated for fusion reaction studies and exotic nuclei synthesis; Yale's heavy-ion linear accelerator (HILAC), commissioned in 1958, produced beams of ions like carbon and oxygen up to 5 MeV per nucleon, advancing understanding of nuclear shell closures and collective rotations.[48] Berkeley's Super Heavy Ion Linear Accelerator (SuperHILAC), upgraded in the mid-1960s to energies exceeding 10 MeV per nucleon, coupled with cyclotrons for tandem operation, enabled the creation of superheavy elements and detailed fission dynamics measurements. Cold War competition spurred this scale-up, with U.S. facilities outpacing rivals in energy and beam quality, though limited exchanges occurred, such as Soviet invitations to their IHEP accelerator in the 1970s for joint nuclear beam tests.[49] By the 1970s and into the 1980s, accelerator complexes integrated multiple stages for precision nuclear astrophysics and reaction rate determinations, with Brookhaven's Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (1959 onward) and planned Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider laying groundwork for quark-gluon plasma probes mimicking early universe conditions.[45] Funding peaked under AEC successors like the Department of Energy, sustaining operations despite shifting priorities toward particle physics, as nuclear data informed weapons simulations and reactor safety without direct testing. This period's accelerators not only refined models of nuclear binding and decay but also highlighted tensions between open science and classified applications, with declassification of select results gradually broadening global access.[44]Fundamental Concepts

Atomic Nucleus Composition and Sizes

The atomic nucleus is composed of protons and neutrons, collectively termed nucleons.[50] Protons carry a positive electric charge equal in magnitude to the elementary charge e, while neutrons possess no electric charge.[51] The number of protons, denoted Z, defines the atomic number and thus the chemical element, whereas the total number of nucleons A = Z + N (with N the neutron number) approximates the atomic mass.[50] These constituents are bound by the strong nuclear force, which overcomes the electrostatic repulsion between protons.[52] Nuclear sizes are characterized by an effective radius R, empirically related to the mass number by R = r_0 A^{1/3}, where r_0 is a constant.[53] For the root-mean-square charge radius, r_0 ≈ 1.2 fm, while the matter radius yields a slightly larger value of approximately 1.4 fm.[53] This scaling arises from the near-constant nuclear density of about 0.17 nucleons per fm³, implying nuclear volume proportional to A.[53] Actual nuclear density profiles exhibit a diffuse surface, but the A^{1/3} dependence holds well for A ≳ 10, with deviations for very light nuclei.[53] For example, the proton (A=1) has a charge radius of roughly 0.84 fm, while heavier nuclei like uranium-238 (A=238) extend to about 7.4 fm.[54] These dimensions, orders of magnitude smaller than atomic radii (~10²–10³ times), underscore the nucleus's extreme density, exceeding that of ordinary matter by a factor of ~10¹⁴.[52]Nuclear Binding Energy and Semi-Empirical Relations

The nuclear binding energy of an atom is the minimum energy required to separate its nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons, equivalent to the energy released when the nucleus forms from those free nucleons.[55] This energy arises from the mass defect, the difference between the mass of the isolated nucleons and the measured mass of the nucleus, converted via Einstein's relation . The binding energy for a nucleus with mass number , atomic number , and neutron number is given bywhere is the proton mass, the neutron mass, the atomic mass (including electrons), and the electron mass; the electron masses nearly cancel for neutral atoms, making the approximation valid since atomic binding energies are negligible compared to nuclear scales.[55] Binding energies per nucleon peak around iron-56 at approximately 8.8 MeV, explaining its relative abundance in stellar nucleosynthesis as the point of maximum stability.[55] To approximate binding energies without detailed quantum calculations, the semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF), also known as the Bethe-Weizsäcker formula, expresses as a sum of terms capturing bulk nuclear properties:

where coefficients are empirically fitted to experimental mass data, and accounts for pairing effects.[55] This liquid-drop-inspired model treats the nucleus as a charged incompressible fluid, balancing attractive strong forces against repulsive Coulomb interactions, and succeeds in reproducing measured binding energies to within a few percent for medium-to-heavy nuclei. The volume term represents the dominant attractive binding from short-range strong nuclear forces, with each nucleon interacting with roughly 12 neighbors in a saturated nuclear density of about nucleons per fm³, yielding MeV.[55] The negative surface term corrects for reduced coordination at the nuclear surface, analogous to surface tension in liquids, with -- MeV reflecting edge effects that lower density slightly outward. The Coulomb term quantifies electrostatic repulsion among protons, modeled as a uniformly charged sphere of radius fm, giving MeV derived from with proton charge .[55] The asymmetry term penalizes deviations from , arising from the Pauli exclusion principle and isospin symmetry in the strong force, which favors balanced proton-neutron ratios; MeV drives neutron excess in heavy nuclei to minimize Coulomb energy.[55] The pairing term (often or MeV, with MeV) provides a small correction for quantum pairing: positive for even-even nuclei (paired protons and neutrons), zero for odd-, and negative for odd-odd, reflecting enhanced stability from Cooper-pair-like correlations in the nuclear superfluid.[55] These terms, when fitted to datasets like the Atomic Mass Evaluation, predict fission barriers and beta-decay energies, though deviations near shell closures highlight the model's macroscopic limitations.[55]

| Term | Coefficient (MeV) | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | Strong force saturation | |

| Surface | -- | Boundary effects |

| Coulomb | Proton repulsion | |

| Asymmetry | Isospin imbalance | |

| Pairing | Nucleon pairing |