Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

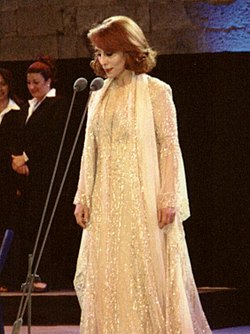

Fairuz

View on Wikipedia

Nouhad Wadie Haddad[b] (born 20 November, 1934 or 21 November, 1935),[a] known as Fairuz,[c] is a Lebanese singer. She is widely considered an iconic vocalist and one of the most celebrated singers in the history of the Arab world. She is popularly known as "The Bird of the East",[d] "The Cedar of Lebanon",[e] "The Moon's Neighbor",[f] and "The Voice of Lebanon",[g] among others.[h]

Key Information

Fairuz began her musical career as a teenager at the national radio station in Lebanon in the late 1940s as a chorus member.[16] Her first major hit, "Itab", was released in 1952 and made her an instant star in the Arab world.[17] In the summer of 1957, Fairuz held her first live performance at the Baalbeck International Festival where she was awarded with the honor of "Cavalier", the highest medal for artistic achievement by Lebanese president Camille Chamoun.[18][19] Fairuz's fame spread throughout the Arab world in the 1950s and 1960s, leading her to perform outside of Lebanon in various Arab capitals, including Damascus, Amman, Cairo, Rabat, Algiers, and Tunis.

Fairuz has received honors and distinctions in multiple countries, including Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Tunisia, the United States, Egypt, and France. Throughout her career, she headlined at the most important venues in the world, such as Albert Hall and Royal Festival Hall in London, Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center and United Nations General Assembly Lobby in New York, the Olympia and Salle Pleyel in Paris, and the Odeon of Herodes Atticus in Athens.[20]

In a career spanning over six decades, Fairuz has recorded nearly 1500 songs, released more than 80 albums, performed in 20 musicals, and sold over 150 million records worldwide, making her one of the highest selling Middle-Eastern artists of all time, and one of the best-selling music artists in the world.[i]

Early life

[edit]

Nouhad Haddad was born on 20 November, 1934 or 21 November 1935, in Beirut into a Syriac Orthodox and Maronite Christian family.[26][27][28] Her father, Wadie, was a Syriac born in Mardin (present-day Turkey) who moved to Lebanon to flee the Sayfo genocide.[29][30] He worked as a typesetter in a print shop.[31] Her mother, Lisa al-Boustani, was born in the village of Dibbiyeh, Mount Lebanon.[32][33][34] The family later moved to Zuqaq al-Blat,[35] a neighborhood in Beirut, where they lived in a single-room house facing the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate school and shared a kitchen with their neighbors.[citation needed]

By the age of ten, Nouhad had become well-known at school for her unusual singing voice. She would regularly sing during school shows and on holidays. This brought her to the attention of Mohammed Flayfel, a well-known musician and a teacher at the Lebanese Conservatory, who happened to attend one of the school's shows in February 1950. Impressed by her voice and performance, he advised her to enroll in the conservatory, which she did. At first, Nouhad's conservative father was reluctant to send her to the conservatory. At the persuasion of his brother, Nouhad's uncle, he eventually agreed to let her go on the condition that her brother accompany her.[36]

Music career

[edit]Early career

[edit]Flayfel took a close interest in Nouhad's talent. He started training her in control of intonation and poetic form,[37] and in an audition, Nouhad was heard singing by Halim el Roumi, head of the Lebanese radio station established in 1938, one of the oldest stations in the Arab world. Roumi was impressed by her voice and noticed that it was flexible, allowing her to sing in both Arabic and Western modes.[9] At Nouhad's request, El Roumi appointed her as a chorus singer at the radio station in Beirut, where she was paid twenty-one U.S dollars every month, which, adjusted for inflation, in 2020 would amount to one hundred ninety-five dollars.[19] He also went on to compose several songs for her and chose for her the stage name Fairuz, which is the Arabic word for turquoise[38] and had been adopted as a stage name by Syrian singer Fayrouz Al Halabiya.[39]

A short while later, Fairuz was introduced to the Rahbani brothers, Assi and Mansour, who also worked at the radio station as musicians. Their chemistry was instant, and soon after, Assi started to compose songs for Fairuz. One of these songs was "Itab" (the third song he composed for her), which was an immediate success in the Arab world. It established Fairuz as one of the most prominent Arab singers at that time.[40]

Fairuz rose to fame during the golden era of Arabic music and is one of the last figures and contributors of that time alive today.[41] Her voice represented the 20th century's Lebanese pop culture.[42] Throughout her career, she has established a style of universality and relatability as she made music that tackled issues ranging from adolescence and love to political plight and patriotism, even "snappy Christmas carols", which made her work accessible to all.[41][43] Fairuz is known for her particularly forlorn style of music, which is a fusion of western and Arab sounds. Her music is set apart by its melancholic and nostalgic humor, along with Fairuz's stoic image as well as yearning voice, that is almost prayer-like, often described by experts as airy, clear, and flexible, different from the common ornamentation style commonly found in Arab music.[41][44][45]

1950s: Establishment of a new star

[edit]Fairuz's first large-scale concert was in 1957, as part of the Baalbeck International Festival which took place under the patronage of Lebanese President Camille Chamoun. She performed in the Folkloric section of the festival representing "The Lebanese Nights". Fairuz was paid one Lebanese pound for that show, but she and the Rahbani brothers would become staples of the festival and featured most years until the civil war in Lebanon. The trio's performances at first were just small skits, but eventually they became full-blown musical operettas, and concerts followed for many years.[9] Fairuz amassed more fame as she and other contemporaneous Arab artists were vocal about the Palestinian cause in their conflict with Israel and produced a number of militaristic and patriotically somber songs for them.[46]

1960s–1970s: Breakthrough and critical acclaim

[edit]

Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers started to garner more attention with their innovative ventures and went on to revolutionise the blueprint for Lebanese music. It started with incorporating western sounds into their music and eventually shaping the Lebanese style of music, since the music had to fit into a certain mold before. This mold was the dominant Egyptian style of music, in the Egyptian dialect that would typically have a duration of thirty minutes.[44] The trio started working with their own prototype, which was shorter three-minute songs in the Lebanese dialect that would tell a story. This change was received as well as it was due to growing discontent for traditional and indigenous music. Beirut at this time was undergoing rapid modernisation and cultural expansion. Some of those who lived in the city were not of Arab background, making it harder to relate to the musical forms of the time.[47] So when Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers introduced a more modern yet still traditional form of music, they drew in mass appeal. This helped reshape the modern Lebanese identity especially in music and would go on to make significant contributions to the history of oriental music.[9] These songs would also customarily included commentary and themes of local and regional socio-political and historical issues.[33] As the 1960s wore on, Fairuz became known as the "First Lady of Lebanese singing", as Halim Roumi dubbed her. During this period, the Rahbani brothers wrote and composed for her hundreds of famous songs, most of their operettas, and three motion pictures.[9] In those productions, they also chose to abandon the popular improvisatory nature of Arab performances in favour of more well-rehearsed and produced ones.[48]

In 1971, Fairuz's fame became international after her major North American tour, which was received with much excitement by the Arab-American and American communities and yielded positive reviews of the concerts. To date, Fairuz has performed in many countries around the globe, including Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, France, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Netherlands, Greece, Canada, United States, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Italy, and her home country, Lebanon.[49]

On 22 September, 1972, Assi suffered a brain hemorrhage and was rushed to the hospital. Fans crowded outside the hospital, praying for him and lighting candles. After three surgeries, Assi's brain hemorrhage was halted. Ziad Rahbani, the eldest son of Fairuz and Assi, at age 17, gave his mother the music of one of his unreleased songs, "Akhadou el Helween" (that he had composed to be sung by Marwan Mahfouz in "Sahriyyi" Ziad's first play). His uncle Mansour Rahbani re-wrote new lyrics for it to be called "Saalouni n'Nass" ("The People Asked Me") which talked about Fairuz being on stage for the first time without Assi.[9][49] Three months after suffering the hemorrhage, Assi attended the premiere performance of that musical, Al Mahatta, in Piccadilly Theatre on Hamra Street. Elias Rahbani, Assi's younger brother, took over the orchestration and musical arrangement for the performance.[46]

In 1978, the trio toured Europe and the Persian Gulf nations, including a concert at the Paris Olympia. As a result of this busy schedule, Assi's medical and mental health began to deteriorate. Assi Rahbani eventually died in 1986, no longer married to Fairuz, but due to the influence his family and Fairuz had in Lebanon, the factions in Beirut had a cease-fire allowing the funeral procession to travel from the Muslim side of the city to where Assi would be buried on the Christian side. Fairuz then began to work almost exclusively with Ziad Rahbani, her son on producing her music.[9][28][38]

Amid the Lebanese Civil War, Fairuz's fame catapulted. Unlike many of her famous peers, she never left Lebanon to live abroad. She did not hold any concerts there with the exception of the stage performance of the operetta Petra, which was performed in both the western and eastern parts of the then-divided Beirut in 1978.[9][36] The war lasted fifteen years (1975–1990), took 150,000 lives, and fostered a divided nation.[50] This was the period where her role as a prominent Lebanese figure would be cemented. She and the Rahbani brothers would frequently express their dissent for the war in their music, and their refusal to take sides and non-partisan stances helped them appeal to all of Lebanon, which then allowed Fairuz to become a voice of reason and unification for the Lebanese people. This was especially important because the war itself was so multifaceted and involved many conflicting opinions between the state and different militias. To the Lebanese, she became a lot more than just an entertainer. She became a representation of Lebanon, as well as stability in a time of insecurity and uncertainty.[44][50]

1980s: A new production team

[edit]After the artistic divorce between Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers in 1979, Fairuz carried on with her son, composer Ziad Rahbani, his friend the lyricist Joseph Harb, and composer Philemon Wahbi.[9] Ziad Rahbani was a constant driving force in the evolution of Fairuz's music style, as he worked to break away from what his parents had previously established. The songs he went on to compose for Fairuz would stray from the nostalgic nationalism that showcased the folkloric style Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers were known for; instead, he and Fairuz would go on to delve into a more modern sound in the form of jazz and funk.[51]

Fairuz made a second and final European Television appearance on French TV on 13 October 1988, in a show called Du côté de chez Fred. Fairuz, who had scheduled a concert at the POPB of Paris Bercy concert hall three days later on 16 October, was the main guest of French TV presenter Frédéric Mitterrand. The program features footage of her rehearsals for her concert at Bercy in addition to the ceremony featuring then French Minister of Culture Jack Lang awarding Fairuz the medal of Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres. It also includes a video montage of her previous movies and concerts. In that show, Fairuz also sang the three songs "Ya hourrié", "Yara" and "Zaali tawwal".

Her first CD, The Very Best of Fairuz, was published in 1987 and contained the emblematic song "Aatini al Nay wa ghanni" (Give me the flute and sing),[52] based on a poem in "The Procession"[53] by Khalil Gibran. It was first sung at the end of the sixties.[54]

1990s–present

[edit]In the 1990s, Fairuz produced six albums (two Philemon Wahbi tributes with unreleased tracks included, a Zaki Nassif album, three Ziad Rahbani albums, and a tribute album to Assi Rahbani orchestrated by Ziad) and held a number of large-scale concerts, most notably the historic concert held at Beirut's Martyr's Square in September 1994 to launch the rebirth of the downtown district that was ravaged by the civil war. She appeared at the Baalbeck International Festival in 1998 after 25 years of self-imposed absence where she performed the highlights of three very successful plays that were presented in the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1992, Madonna used some parts of Fairuz's songs in her album without permission; the singers settled the matter outside of court, but Madonna's album and single were prohibited in Lebanon.[55]

She also performed a concert in Las Vegas at the MGM Grand Arena in 1999 which was attended by over 16,000 spectators, mostly Arabs. Ever since, Fairuz has held sold-out concerts at the Beiteddine International Festival (Lebanon) from 2000 to 2003, Kuwait (2001), Paris (2002), the United States (2003), Amman (2004), Montreal (2005), Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Baalbeck, BIEL (2006), Athens,[56] Amman (2007) Damascus, and Bahrain (2008).

Her first album in the new millennium, Wala Keef, was released in 2002.[57]

On 28 January 2008, Fairuz performed at the Damascus Opera House in an emotional return to the Syrian capital, where she played the lead role in the musical Sah el-Nom (Good Morning), after more than two decades of absence from the country, in one of a series of events highlighting UNESCO's designation of Damascus as the Capital of Arab Culture that year. Commenting on the event, the BBC wrote: "Every day the sun rises over Syria you hear one voice across the country—Fairuz, the legendary Lebanese singer and greatest living Arab diva". Syrian historian, Sami Moubayed, said that the Syrians were thrilled about the performance and that Fairuz reminded them of the "good old days". People from all ages attended the concert and the auditorium was packed with listeners. Fairuz said that she had never seen such an audience in her life. However, her decision to perform there drew criticism from Lebanese politicians who considered Syria to be a hostile nation.[58][59]

Fairuz's new album entitled Eh... Fi Amal was released on 7 October 2010, produced by Fairuz productions and written entirely by her son Ziad Rahbani. Two concerts took place at BIEL Center in Beirut, Lebanon, on 7 and 8 October.[60]

On 22 September 2017, Fairuz released her first album in seven years, titled Bebalee and produced by her daughter Rima Rahbani.[61] On 21 June, Fairuz had released the first single from the album, "Lameen", in commemoration of her late husband Assi Rahbani. It was inspired by the French song "Pour qui veille l'étoile" and was adapted into Arabic by Rima Rahbani.[62][63][64]

On 1 September 2020, French president Emmanuel Macron visited Fairuz in her house during his trip to Lebanon after the Beirut explosion.[65]

Fairuz made a rare public appearance in July 2025, on the occasion of the passing of her son, Ziad Rahbani, to attend his funeral.[66]

Controversies

[edit]2008 Damascus concert

[edit]The 2008 concert in Damascus angered some of her fans and several Lebanese politicians who described Syria as "enemy territory in the grip of a brutal secret police force". Walid Jumblatt, leader of the Druze Progressive Socialist Party, accused Fairuz of "playing into the hands of Syrian intelligence services", while fellow party member Akram Chehayeb said that "those who love Lebanon do not sing for its jailers", in reference to the three-decades-long Syrian occupation of Lebanon. Even some Syrian opposition activists called on her to boycott the event as just three years prior Syria had been accused of carrying out a series of assassinations on the Lebanese.[67] This came amid a political crisis in Lebanon between pro- and anti-Syria factions. As well as a renewed Syrian government crackdown on dissent that same day during which several people were arrested, including opposition figure Riad Seif and twelve other activists of the anti-government Damascus Declaration.[9][68]

A poll conducted a week before the concert by NOW Lebanon, a Lebanese web portal sympathetic to the anti-Syria March 14 Alliance, showed that 67% of the respondents were opposed to Fairuz's appearance in Damascus, with one of the website's editorials saying that "this was not the moment for a musical love-in". Supporters of Fairuz counterclaimed that she has always been above politics.[67] Fairuz refrained from commenting on the controversy. However, in a letter to the event's organisers, she said that the concert should be viewed from a cultural perspective, and wrote: "Damascus is not a cultural capital for this year only, but will remain a role model of art, culture and authenticity for the coming generations." She also told the head of the organisers that she felt it was a return to her second home. Syrian commentator Ayman Abdelnour said that Fairuz was performing to the Syrian people, not their rulers. Her brother-in-law and her former partner Mansour Rahbani also defended her decision to perform there, saying it was "a message of love and peace from Lebanon to Syria".[58][59][69]

In 1969, Fairuz's songs were banned from radio stations in Lebanon for six months because she refused to sing at a private concert in honour of Algerian president Houari Boumedienne. The incident only served to increase her popularity.[citation needed] Fairuz said that while always willing to sing to the public and to various countries and regions, she would never sing to any individual.[70]

Lawsuits

[edit]Since many of the Rahbanis' works were co-written by Assi's brother Mansour, in June 2010, a year after Mansour's death in January 2009, a Lebanese court banned Fairuz from singing material that involved his contributions. The issue began when Mansour's children filed a lawsuit against Fairuz when she was set to perform the song "Ya'ish Ya'ish" at the Casino du Liban. As a result, Fairuz could not perform such works without Mansour's children's permission. The court's decision led to protests around the world in response to what her fans perceived as an act of "silencing". Hundreds gathered in front of the National Museum of Beirut, led by a number of Arab artists, including Egyptian actress Ilham Chahine who flew to Lebanon in order to join the sit-in. "She is a great artistic personality who has entertained millions for decades. We cannot keep silent over this humiliating attitude to her and to art and artists in general. Fairuz to me is above all laws. She is like the mother whom, even when she errs, we are eager to forgive," Chahine added. Ian Black wrote on The Guardian: "Outrage over her silencing has been a reminder of the extraordinary loyalty she still inspires across the region". Other reactions included a protest concert in Egypt, and a "Shame!" headline displayed by Emirati newspaper Al-Ittihad.[11][71]

Alleged political affiliations

[edit]Fairuz's son, Ziad Rahbani, sparked controversy in December 2013 during an interview with the Al-Ahed website when asked whether his mother shared his supportive stance on the political vision of Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, a dominant but highly controversial political and military force in Lebanon. Ziad replied: "Fairuz is very fond of Sayyed Hassan [Nasrallah], although she will be displeased with me, as she was after my last television interview when I revealed some personal information and she quickly interrupted me".[72] There were strong reactions to this statement, which went viral on social media,[73] and the country's different media outlets did not deviate from their political stances when reacting to Ziad's words.[74] Politicians and celebrities stepped in as well, some of whom objected to affiliating Fairuz to one side of Lebanon's political divide over another, including Druze leader Walid Jumblatt who said: "Fairuz is too great to be criticised, and at the same time too great to be classified as belonging to this or that political camp". "Let us keep her in her supreme position, and not push her to something she has nothing to do with," Jumblatt added.[75] Ziad, who claims to speak on his mother's behalf "because she prefers to remain silent", responded to his critics by saying: "Apparently it isn’t allowed in the age of strife for the princess of classy Arab art to voice love for the master of resistance".[75] Nasrallah, commenting on the issue during a speech, stated: "An educated highly respected thinker and artist, who may be espoused different ideologies, might disagree with you on political matters, but personally have [a] fondness for you, because of your character, conduct, sacrifices and so on. If such a person were to say that he or she liked someone, then all hell would break loose".[72]

Performances and persona

[edit]Fairuz has performed in many countries around the globe including Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, France, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Netherlands,[76] Greece, Canada, United States, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Italy, and her home country Lebanon.

During her performances, Fairuz is known to take on a very rigid and cold stance, due to her stage fright. She claims that the hierarchic nature of her performances is because she is singing as if she were praying.[43][77] She is also described as being incredibly reserved and modest in the way a mother would be, and embodies the Lebanese woman at home.[77]

Personal life

[edit]

Very little is known about Fairuz's personal life and affairs, as she is described as having a hermetic nature and separates her private life as Nouhad from her public persona of Fairuz.[77]

Born to a Syriac Orthodox and Maronite Christian family, Fairuz converted to Greek Orthodoxy when she married Assi Rahbani (1923–1986),[78] one of the Rahbani brothers who helped shape her singing career, on 23 January 1955.[9] The ceremony took place at the Greek-Orthodox Annunciation Church of Beirut. The couple had four children: Ziad (1956–2025), a composer, playwright and pianist; Hali (born 1958, paralysed since early childhood after meningitis); Layal (born 1960, died in 1988 of a stroke), also a composer; and Rima (born 1965), a photographer and film director.[77] Fairuz has a younger sister, Hoda Haddad, who has worked as a singer and actress.

Rahbani family tree

[edit]Theatrical works

[edit]Most of the works of the Rahbani trio (Fairuz, Assi, and Mansour) consisted of musical plays or operettas. The Rahbani brothers produced 25 popular musical plays (20 with Fairuz) over more than 30 years, and are credited as having been one of—if not the very first—to produce world-class Arabic musical theatre.[9][38]

The musicals combined storyline, lyrics and dialogue, musical composition varying widely from Lebanese folkloric and rhythmic modes to classical, westernised, and oriental songs, orchestration, and the voice and acting of Fairuz. She played the lead roles alongside singers/actors Nasri Shamseddine, Wadih El Safi, Antoine Kerbaje, Elie Shouayri (Chouayri), Hoda Haddad (Fairuz's younger sister), William Haswani, Raja Badr, Siham Chammas (Shammas), Georgette Sayegh, and many others.[79][5]

The Rahbani plays expressed patriotism, unrequited love and nostalgia for village life, comedy, drama, philosophy, and contemporary politics. The songs performed by Fairuz as part of the plays have become immensely popular among the Lebanese and Arabs around the world.[40]

The Fairuz-Rahbani collaboration produced the following musicals (in chronological order):

- Ayyam al Hassad (Days of Harvest – 1957)

- Al 'Urs fi l’Qarya (The Wedding in the Village – 1959)

- Al Ba'albakiya (The Girl from Baalbek) – 1961)

- Jisr el Amar (Bridge of the Moon – 1962)

- Awdet el 'Askar (The Return of the Soldiers – 1962)

- Al Layl wal Qandil (The Night and the Lantern – 1963)

- Biyya'el Khawatem (Ring Salesman – 1964)

- Ayyam Fakhreddine (The Days of Fakhreddine – 1966)

- Hala wal Malik (Hala and the King – 1967)

- Ach Chakhs (The Person – 1968–1969)

- Jibal Al Sawwan (Sawwan Mountains – 1969)

- Ya'ich Ya'ich (Long Live, Long Live – 1970)

- Sah Ennawm (Did you sleep well? – 1970–1971 – 2006–2008)

- Nass min Wara' (People Made out of Paper – 1971–1972)

- Natourit al Mafatih (The Guardian of the Keys – 1972)

- Al Mahatta (The Station – 1973)

- Loulou – 1974

- Mais el Reem (The Deer's Meadow – 1975)

- Petra – 1977–1978

Most of the musical plays were recorded and video-taped. Eighteen of them have been officially released on audio CD, two on DVD (Mais el Reem and Loulou). An unauthorised version of Petra and one such live version of Mais el Reem in black and white exist. Ayyam al Hassad (Days of Harvest) was never recorded and Al 'Urs fi l’Qarya (The Marriage in the Village) has not yet been released (yet an unofficial audio record is available).[38][page needed]

Honors and awards

[edit]For decades, most radio stations in the Arab world have started their morning broadcast with a Fairuz song, and her songs were wildly popular during the Lebanese Civil War, as the people could expect to hear a patriotic melody of peace and love.[11][77][80] The Guardian stated that "she sang the story of a Lebanon that never really existed" and "essentially helped build the identity of Lebanon, just 14 years after it became an independent country."[81] Fairuz is held in high regard in Lebanese culture because, in a region divided by many conflicts and opinions, she acts as a symbol of unity.[82] In 1997, Billboard stated "even after five decades at the top, [Fairuz] remains the supreme Diva of Lebanon".[83] In 1999, The New York Times described her as "a living icon without equal" and stated that her emergence as a singer paralleled Lebanon's transformation from a backwater to the vibrant financial and cultural heart of the Arab world.[84]

In a 2008 article, BBC described her as "the legendary Lebanese singer and greatest living Arab diva".[85] In an article about world music, The Independent stated, "All young female singers in this region seem to be clones of her" and that "she's such an important artist that you have to get to grips with her".[86]

Fairuz has received multiple awards and tokens of recognition throughout her career, including the Key to the Holy City (by the Jerusalem Cultural Committee in 1973), the Jordanian Medal of Honor (by King Hussein in 1975), the Jerusalem Award (by the Palestinian Authority) and the Highest Artistic Distinction (by Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 1998), as well as being nominated Knight of the National Order of the Cedar, Commander of Arts and Letters (by French president François Mitterrand in 1988) and Knight of the Legion of Honor (by French president Jacques Chirac in 1998).[17][87]

Filmography

[edit]Cinema

[edit]| Year | Title (English translation) |

Role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | Biya' Al Khawatem (The Rings Salesman) |

Rima | [88] |

| 1967 | Safar Barlik (Mobilization) |

Adla | [89] |

| 1968 | Bint Al Haress (The Guard's Daughter) |

Najma | [90] |

Television

[edit]Lebanese Television has featured appearances by Fairuz in the following television programmes:[91]

- Al Iswara (The Bracelet)

- Day'it El Aghani (Village of Songs)

- Layali As'Saad (Nights of Happiness)

- Al Quds fil Bal (Jerusalem in my Mind)

- Dafater El Layl (Night Memoirs)

- Maa Al Hikayat (With Stories)

- Sahret Hobb (Romantic Evening)

- Qasidat Hobb (A Love Poem), also presented as a musical show in Baalbeck in 1973

Discography

[edit]Fairuz possesses a relatively large musical repertoire. Though sources disagree on the exact number, she is generally credited with between fifteen hundred and three thousand songs.[77][92]

Around 85 Fairuz CDs, various vinyl formats, and cassettes have been officially released. Most of the songs that are featured on these albums were composed by the Rahbani brothers. Also featured are songs by Philemon Wehbe, Ziad Rahbani, Zaki Nassif, Mohamed Abd El Wahab, Najib Hankash, and Mohamed Mohsen.

Many of Fairuz's numerous unreleased works date back to the 1950s and 1960s, and were composed by the Rahbani brothers (certain unreleased songs, the oldest of all, are by Halim el Roumi). A Fairuz album composed by Egyptian musician Riad Al Sunbati (who has worked with Umm Kulthum) was produced in 1980 but is unlikely to be released. There are also fifteen unreleased songs composed by Philemon Wehbe and 24 unreleased songs composed by Ziad Rahbani in the 1980s.

Fairuz has also released a live album on Folkways Records in 1994, entitled Lebanon: The Baalbek Folk Festival.[93]

In popular culture

[edit]The character in Yasmine El Rashidi's novel Chronicle of a Last Summer listens to Fairuz's song "Shat Iskandaria", a song about love and longing for the coastal city of Alexandria that is noted for its melodic style influenced by Balkan folk music.[94]

See also

[edit]- Rahbani brothers

- Wadih El Safi

- Zahrat al-Mada'en

- Ziad Rahbani

- Julia Boutros, "The Lioness of Lebanon"

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Haddad's birth year is disputed, with some sources indicating 1934[1][2][3][4] and some 1935.[5][6][7][8] The Encyclopædia Britannica cites her birth date as November 20, 1934 according to the records of the Lebanese Ministry of the Interior and November 21, 1935 according to her family.[9]

- ^ Arabic: نهاد وديع حداد, romanized: Nuhād Wadīʿ Ḥaddād, Lebanese Arabic pronunciation: [nʊˈhaːd waˈdiːʕ ħadˈdaːd].

- ^ Also spelled Fairouz, Feyrouz or Fayrouz; Arabic: فيروز, romanized: Fayrūz, pronounced [fajˈruːz].

- ^ Arabic: عصفورة الشرق, romanized: ʿAṣfūrat aš-Šarq.

- ^ Arabic: أرزة لبنان, romanized: ʾArzat Lubnān.

- ^ Arabic: جارة القمر, romanized: Jārat al-Qamar.

- ^ Arabic: صوت لبنان, romanized: Ṣawt Lubnān.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[10][11][12][13][14][15]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[21][22][23][24][25]

References

[edit]- ^ Abi Rafeh, Lara (21 November 2024). "بالفيديو: 90 سنة من الحبّ.. 90 سنة من فيروز". MTV Lebanon (in Arabic). Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "Fairouz turns 90: Lebanon's beloved icon marks milestone amid Israel war". The New Arab. 21 November 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "Beloved singer Fairuz, a symbol of unity in crisis-torn Lebanon, turns 90". France 24. 21 November 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ Succar, Mariella (21 November 2024). "Fairuz turns 90: A celebration of Lebanon's legendary voice". LBCI. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Fairuz | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "فيروز من "جوار القمر" إلى عمق التاريخ". Aljazeera (in Arabic). Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "المطربة فيروز". Mbc3.mbc.net (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "في مثل هذا اليوم ولدت المغنية اللبنانية نهاد وديع "فيروزnohad hadda"". Zaytoday.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Christopher Stone, Fairouz at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Nora Boustany (26 April 1987). "The Sad Voice of Beirut". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c Black, Ian (29 July 2010). "Fans lend their voices to Fairouz, the silenced diva". The Guardian.

- ^ "Lebanese diva Fairuz's concert delights Syrian fans". Agence France-Presse. 28 January 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ Khaled Yacoub (28 January 2008). "Lebanese diva arouses emotion, controversy in Syria". Reuters. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ "فيروز .. 80 عاما من طرب 'قيثارة السماء'" [Fayrouz.. 80 years of singing "Heaven's Harp"]. Sky News Arabia (in Arabic). 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Virtually Unknown in the West, But She's an Icon of the Arab World". Messy Nessy Chic. 7 December 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Lesser known facts about Fairouz as legendary singer turns 84". gulfnews.com. 21 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Fairuz". www.aub.edu.lb.

- ^ "How Did Fairuz Become an International Star?". MTV Lebanon. 21 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Børre Ludvigsen Web Archive". libraries.aub.edu.lb.

- ^ "Fairuz: Legacy of a Star" (PDF). AUBMC. 2016.

- ^ "Eight reasons why Fairouz is the greatest Arab diva of all time". The National. 21 November 2016.

- ^ Sami Asmar (Spring 1995). "Fairouz: a Voice, a Star, a Mystery". Al Jadid. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ "Iconic Fairouz remains most listened-to Arab singer as she turns 80". Al Bawaba.

- ^ Boulos, Sargon (1981). Fairouz – Legend and Legacy. Forum for International Art and Culture. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Arab Stars on the Global Stage". Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ FatmaAydemir, Sami Rustom: Libanesische Sängerin Fairouz: Die fremde Stimme, taz.de, 20 November 2014 (German)

- ^ Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo, eds. (1999). World music: the rough guide. Africa, Europe and the Middle East, Volume 1. Rough Guides. p. 393. ISBN 9781858286358.

- ^ a b "Mansour Rahbani: Obituary". The Telegraph. 8 February 2009.

- ^ Atallah, Samir (30 November 2005). ""سبعون" البنت السريانية التي جاءت من ماردين". An-Nahar. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ أبو فخر, صقر (2007), الدين والدهماء والدم: العرب وإستعصاء الحداثة, Beirut: المؤسسة العربية للنشر والدراسات, p. 274, ISBN 978-9953-36-946-4

- ^ Neil Macfarquhar (18 May 1999). "This Pop Diva Wows Them in Arabic". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Centennial of Assi al-Rahbani shines light on his cherished musical legacy". en.majalla.com. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ "History | Boustani Congress". 30 November 2020. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ "Fairouz: a Voice, a Star, a Mystery | Al Jadid". aljadid.com. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "بالصور.. هذا منزل فيروز المهجور في بيروت". العربية (in Arabic). 12 December 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2025.

- ^ a b "Fairuz | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Fairuz | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Stone, Christopher (12 September 2007). Popular Culture and Nationalism in Lebanon. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203939321. ISBN 978-0-203-93932-1.

- ^ Amnon Shiloh, מוזיקה רבת־פנים וזהויות, p. 484-485, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev – Studies, Multidisciplinary Journal of Israel Research, 2016

- ^ a b "Fairuz - her music". almashriq.hiof.no. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "9 facts about legendary Lebanese singer Fayrouz". EgyptToday. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Vocal Performance - Fairuz". sonicdictionary.duke.edu. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Neil (18 May 1999). "This Pop Diva Wows 'Em In Arabic (Published 1999)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "Fairuz: Lebanon's Voice Of Hope". NPR.org. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Longley, Martin (9 July 2020). "Fairuz and Her Family Fusions". The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Fairuz". www.aub.edu.lb. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Fairuz - Biography". almashriq.hiof.no. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Fairuz - her music". almashriq.hiof.no. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Fairuz / فيروز". www.antiwarsongs.org. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b Paul Kingston, William L. Ochsenwald, Lebanese Civil War at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Haugbolle, Sune (2016). "The Leftist, the Liberal, and the Space in Between: Ziad Rahbani and Everyday Ideology". The Arab Studies Journal. 24 (1): 168–190. ISSN 1083-4753. JSTOR 44746851.

- ^ "Fairuz - Paroles de " Atini Alnay Wa Ghanny- أعطني الناي و غن " + traduction en anglais". Lyricstranslate.com.

- ^ Gibran, Kahlil (20 December 2011). A Treasury of Kahlil Gibran. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781453235546 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Album Reviews: The Very Best of Fairuz". 20 December 2008. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008.

- ^ "Happy Birthday Fairouz! Here Are 7 Facts About the Legendary Singer". Vogue Arabia. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Raed Rafei (15 July 2007). "Haunted by her songs of love, peace". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Wala Keef by Fairouz, January 2002, retrieved 13 December 2020

- ^ a b Sinjab, Lina (7 February 2008). "Lebanese diva opens Syrian hearts". BBC. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ a b Blanford, Nicholas (28 January 2008). "Fairouz fans angry over the diva's concert in Syria". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ "Fairouz | Aghanyna". Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Bebalee, 22 September 2017, retrieved 13 December 2020

- ^ "Fayrouz gives glimpse of upcoming album". Euronews. 21 June 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Lebanese icon Fayrouz announces release of new single 'Lameen' – Music – Arts & Culture". Al-Ahram. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Fairouz Just Released A New Song!". The961. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Macron reassures protesters after meeting Lebanon's symbol of unity, singer Fairouz". Reuters. 31 August 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Farhat, Beatrice (28 July 2025). "In rare appearance, Fairuz mourns son Ziad Rahbani as Lebanon bids farewell". www.al-monitor.com. Beirut. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Fairouz fans angry over the diva's concert in Syria". The Christian Science Monitor. 28 January 2008. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Ganz, Jacob (30 July 2010). "Royalty Dispute May Silence Fairouz". NPR.org. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Oweis, Khaled Y. (8 January 2008). "Lebanese diva arouses emotion, controversy in Syria". Reuters. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ Al Yafai, Faisal (7 August 2010). "Fairuz: Lebanon's quavering voice". The National. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

1969: Banned from radio stations for six months after refusing to perform a private concert for the president of Algeria

- ^ Ganz, Jacob (30 July 2010). "Royalty Dispute May Silence Fairouz". NPR. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ a b Aziz, Jean (27 December 2013). "Famous diva's 'fondness' for Nasrallah stirs controversy". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ "Nasrallah and Jumblatt weigh in on Fairouz fallout". The Daily Star. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Bulos, Nabih (20 December 2013). "Lebanese singer stirs controversy with 'love' of Hezbollah chief". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b McNamara, Whitney (27 December 2013). "Uproar over legendary Fairuz's 'love' of Hezbollah chief". Al Arabiya. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Blok, Arthur (27 June 2011). "Fairuz wows Amsterdam". NOW Lebanon. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

Holland Festival organizers were literally glowing with pride as legendary singer Fairuz stepped on stage on Sunday night at Amsterdam's Royal Theater Carré.

- ^ a b c d e f "Macron's visit to Fairuz signifies French esteem for Lebanon's No. 1 diva". Arab News. 1 September 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Fairouz: Still going strong at 80". Arab News. 22 November 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Fairuz | Album Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Iconic Fairouz remains most listened-to Arab singer as she turns 80". 22 November 2015.

- ^ Atallah, Nasri (4 January 2016). "An insider's cultural guide to Beirut: 'a beautiful, rowdy, intoxicated mess'". The Guardian.

- ^ "Macron reassures protesters after meeting Lebanon's symbol of unity, singer Fairouz". Reuters. 31 August 2020.

- ^ goo.gl/376cJk [dead link]

- ^ Macfarquhar, Neil (18 May 1999). "This Pop Diva Wows 'Em In Arabic". The New York Times.

- ^ "Lebanese diva opens Syrian hearts". BBC News. 7 February 2008.

- ^ "The beginner's guide to world music". Independent.co.uk. 27 July 2006.

- ^ "Fairuz". aub.edu.lb. American University of Beirut. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ ""بياع الخواتم" أول تجربة سينمائية لفيروز". Al-Ittihad (in Arabic). 22 February 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ دبس, زهير (22 November 2017). "سفر برلك ايقونة الاستقلال الرحباني". Manateq. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "فيروز – ﺗﻤﺜﻴﻞ – فيلموجرافيا، صور، فيديو". elCinema.com.

- ^ "Fairuz Online: Fairuz, Fairouz, Fayrouz Feyrouz Feiruz". fairuzonline.com. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Fairuz: Celebrated Lebanese singer turns 85 | DW | 20.11.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Lebanon: The Baalbek Folk Festival". Folkways Records. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "A Love Song Still Divides a Region". New Lines Magazine.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Fairuz songs' lyrics, with information on musicians/lyricists (Arabic)

- A Diva Brightens a Dark Time in Beirut (2006 article in The New York Times)

- Fairuz discography at Discogs

- Fairuz at IMDb

Fairuz

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Childhood and Family Origins

Nouhad Wadie Haddad, later known as Fairuz, was born on November 21, 1935, in Beirut, Lebanon, into a working-class Christian family of limited financial resources.[8] Her father, Wadi' Haddad, originated from Mardin in southeastern Turkey, where he survived the Assyrian genocide during the Ottoman era, and worked as a typesetter in a Beirut print shop to support the household.[9][10] Her mother, Lisa al-Bustani, from a Maronite background in Mount Lebanon, served as a homemaker raising their four children—Nouhad as the eldest, followed by Youssef, Hoda, and Amal—in straitened circumstances typical of many migrant Christian families in interwar Lebanon.[8] The Haddad family resided in the Zokak al-Blat neighborhood of Beirut, a densely populated, cobblestoned area housing laborers and artisans amid the economic transitions of the French Mandate period, where post-Ottoman displacement and urban migration concentrated working-class Syriac and Maronite communities in modest stone dwellings, often single-room units.[11][12] This environment underscored the socioeconomic realities for Christian minorities, reliant on manual trades amid Lebanon's emerging confessional economy, with the family's relocation from rural or peripheral origins to central Beirut reflecting broader patterns of internal migration for survival rather than prosperity.[9][11] Fairuz's upbringing in this milieu exposed her early to the intertwined Syriac paternal heritage—marked by liturgical chants and oral folk elements—and Maronite maternal traditions, fostering a cultural rootedness in Christian communal practices within Beirut's heterogeneous yet economically divided urban fabric, though constrained by the practical demands of poverty.[12] The household's reliance on her father's printing wage highlighted the precarity of such lives, as Lebanon navigated independence in 1943 amid persistent class disparities for non-elite Christians.[9][11]Initial Musical Influences and Training

Nouhad Haddad, born in Beirut in 1935, exhibited a natural talent for singing from a young age, regularly performing in neighborhood gatherings and school events during the 1940s.[13] By approximately age ten, she had gained local recognition for her distinctive voice, participating in school shows and religious holiday performances in the diverse cultural environment of Zokak el-Blat.[13] This period exposed her to Lebanon's interwar musical landscape, including traditional tarab styles broadcast from Egypt and regional folk elements prevalent in urban Christian and Muslim communities.[14] Haddad joined her public school's choir, where her abilities were further honed through group singing of anthems and ceremonial pieces.[4] Around age 12 in 1947, a teacher from the Lebanese National Higher Conservatory of Music, Muhammad Flayfel, identified her potential and provided introductory vocal guidance, emphasizing precise pronunciation via Quranic recitation techniques and practical advice such as avoiding acidic foods to preserve timbre.[15] [14] She also sang in local church settings, absorbing melodic structures from Syriac Orthodox and Maronite hymns reflective of her mixed heritage.[16] These experiences culminated in informal vocal practice amid familial emphasis on education, with Haddad listening intently to Egyptian radio broadcasts of artists like Umm Kulthum, whose tarab performances influenced her phrasing and emotional delivery.[14] In 1950, encouraged by a family acquaintance, she auditioned successfully for the chorus at Lebanese Radio, leveraging her developed skills without prior professional recording experience.[13]Professional Beginnings

Radio Discovery and Debut Recordings

In early 1950, at the age of 15, Nouhad Wadie Haddad (later known as Fairuz) auditioned at the Lebanese Broadcasting Station (Radio Lebanon) in Beirut, where musician and choir director Mohammed Flayfel, impressed by her distinctive vocal timbre, selected her to join the station's choir.[17] Flayfel, a prominent figure in Lebanon's nascent post-independence music scene, directed the choir and facilitated her entry, providing a salaried position that marked her professional entry into broadcasting. This opportunity arose amid Radio Lebanon's mandate, established after the country's 1943 independence, to foster national cultural identity by scouting and promoting local talent through state-funded programs, contrasting with the dominance of Egyptian broadcasts in the Arab world.[18] Her initial broadcasts featured her as a choir member performing traditional Lebanese folk arrangements under Flayfel's guidance, emphasizing modal scales and rural themes typical of the era's radio output. During this period at the station, composer Halim El Roumi, another key figure, renamed her "Fairuz" (meaning "turquoise" in Arabic) to evoke her clear, jewel-like voice, a pseudonym that replaced her [birth name](/page/Birth name) for her public career.[19] By 1952, Fairuz transitioned to solo recordings, with "Itab" (meaning "Reproach") becoming her breakthrough single; recorded in Damascus at a Syrian radio station due to limited local facilities, it blended traditional tarab melodies with emerging orchestration, achieving rapid popularity across Lebanon and Syria.[20] These debut efforts highlighted Radio Lebanon's economic role in artist development, offering modest stipends and airtime that enabled recordings without commercial viability risks, while institutional scouting prioritized raw talent over formal training—Fairuz had only briefly attended the Lebanese Conservatory on Flayfel's recommendation before focusing on radio work. Early singles like "Itab" and contemporaries such as "Gheeb Ya Amar" maintained conservative arrangements rooted in folk traditions, setting the stage for later innovations but establishing her as a voice of authentic Lebanese expression in the post-colonial cultural landscape.[21][22]Partnership with the Rahbani Brothers

Fairuz first collaborated with the Rahbani brothers, Assi and Mansour, in the early 1950s through their shared work at Radio Lebanon, where the brothers contributed compositions and she performed as a vocalist.[23] This partnership introduced a distinctive folk-orchestral style characterized by layered instrumentation, rural Lebanese melodies, and poetic lyrics drawing from mountain folklore and cultural traditions.[23] [24] The initial compositional output included the song "ʿItāb" ("Blame"), recorded around 1952, which blended romantic themes with emergent Lebanese nationalist undertones and marked the onset of their prolific synergy.[23] [20] By formalizing their creative alliance, the trio produced over 50 songs within the first three years, emphasizing authentic Maronite heritage elements like dialectal expression and pastoral imagery while appealing to a pan-Lebanese audience.[24] [25] This collaboration extended to live presentations, culminating in the group's debut at the Baalbeck International Festival in 1957, where Fairuz performed folkloric segments such as "The Lebanese Nights" under the Rahbanis' direction, establishing a template for integrating orchestral arrangements with traditional motifs.[23] [24] The Rahbanis' approach prioritized empirical fidelity to regional musical structures over abstract experimentation, yielding verifiable hits that propelled Fairuz's recordings across Arab radio networks by the decade's end.[23]Career Trajectory

1950s-1960s: Rise to Stardom and National Icon Status

Fairuz's popularity surged in the mid-1950s through recordings and radio broadcasts that resonated across the Arab world, building on her earlier radio work to establish her as a leading voice in Lebanese music.[26] Her collaboration with the Rahbani brothers produced folk-infused songs that captured national sentiment, drawing large audiences and setting the stage for live performances.[27] The summer of 1957 marked a turning point with her debut at the Baalbeck International Festival, Lebanon's premier cultural event aimed at boosting tourism during the post-independence era of stability.[28] Performing amid the ancient Roman ruins, Fairuz received the "Cavalier" honor from President Camille Chamoun, recognizing her contribution to elevating Lebanese heritage on the global stage.[29] This appearance, sponsored by the government to promote national identity and attract visitors, drew massive crowds and media attention, transforming her from radio star to live sensation.[30] Throughout the 1960s, Fairuz's annual Baalbeck engagements and tours to Arab capitals like Damascus reinforced her role in cultural diplomacy, as the festival's fusion of ancient sites with modern performances symbolized Lebanon's cosmopolitan prosperity.[5] Her music, emphasizing Lebanese folklore without overt sectarian references, positioned her as a unifying figure amid the country's multi-confessional fabric, with public reception evidenced by sold-out events and widespread radio play.[12] By decade's end, her discography from this period had propelled record sales contributing to her career total exceeding 80 million albums worldwide, per industry figures, underscoring her commercial dominance.[23]1970s-1980s: Peak Productions and Style Evolution

During the 1970s and 1980s, Fairuz sustained prolific output amid the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990), which caused an estimated 150,000 fatalities and displaced hundreds of thousands.[31] [32] She released dozens of albums in this period, continuing collaborations with the Rahbani brothers on musicals that emphasized enduring themes of Lebanese identity and resilience despite production challenges from conflict-induced disruptions and temporary exiles.[33] These works maintained stylistic roots in folk and orchestral arrangements while adapting to wartime constraints, with recordings often serving as cultural anchors for audiences facing societal fragmentation. The 1979 album Wahdon exemplified peak production, featuring compositions by Ziad Rahbani alongside Assi and Mansour Rahbani, and addressing motifs of solitude and displacement reflective of war-era migrations.[34] Released on Zida Records, it included the track "Al Bosta," blending traditional Arabic melodies with emerging rhythmic innovations, and achieved enduring popularity through its emotional resonance with displaced listeners.[35] Rahbani musicals persisted, such as adaptations staged amid intermittent ceasefires, prioritizing narrative continuity over political commentary to foster communal escapism from the war's empirical devastation.[36] By the 1980s, following Assi Rahbani's death in 1986, Fairuz transitioned toward son Ziad Rahbani's arrangements, incorporating modern jazz and urban influences that evolved her sound from pastoral folk toward contemporary fusion.[37] Albums like those produced by Ziad featured layered instrumentation and introspective lyrics, sustaining sold-out international performances where her voice provided psychological relief, causally linked to high demand as a non-partisan refuge amid Lebanon's 150,000-death toll and sectarian divides.[37] [31] This stylistic shift preserved core thematic consistency—rooted in personal and national longing—while enhancing adaptability, evidenced by continued theatrical works that drew audiences despite restricted domestic venues during Beirut's partition.[38]1990s-2010s: International Tours and Production Shifts

Following the Lebanese Civil War, Fairuz resumed live performances with appearances at the Baalbeck International Festival in 1998, marking her return to major Lebanese stages.[39] She subsequently held sold-out concerts at the Beiteddine International Festival in Lebanon from 2000 to 2003, alongside international engagements including Kuwait in 2001 and Paris in 2002.[40] A performance in Las Vegas in 1999 drew over 16,000 attendees, underscoring her draw among Arab diaspora audiences.[41] Fairuz's output during this period shifted toward selective collaborations, particularly with her son Ziad Rahbani, as evidenced by the 2001 album Sings Ziad Rahbani, featuring interpretations of his compositions.[42] This reflected adaptations to her aging voice and a move away from the prolific Rahbani Brothers era, with fewer new releases overall. Her final major concert occurred in Beirut on October 7-8, 2010, after which she largely withdrew from live performances.[43] Commercial success persisted through enduring popularity in Arab diaspora communities, where her catalog maintained strong sales, contributing to over 150 million records sold worldwide across her career. However, later tours emphasized nostalgic repertoires, with critiques noting reliance on established hits amid reduced innovation.[44]2020s: Seclusion, Tributes, and Family Loss

Fairuz maintained a profound seclusion throughout the 2020s, with no new musical recordings or live performances following her final international tour in the early 2010s. At age 89 upon entering the decade and turning 90 on November 21, 2024, her withdrawal aligned with advanced age and a deliberate retreat from public life, as evidenced by her quiet lifestyle shielded from media scrutiny. This period coincided with Lebanon's multifaceted crises, including the economic collapse initiating in late 2019—marked by currency devaluation exceeding 90% and hyperinflation—and the August 4, 2020, Beirut port explosion that killed 218 people and devastated the capital's infrastructure. Amid these events, public engagement with Fairuz's oeuvre shifted to archival releases and tributes, such as remixes of classics like "Li Beirut" and global celebrations of her enduring catalog, underscoring her symbolic role without active participation.[45][46] The decade's most notable event piercing her isolation was the death of her son, composer and playwright Ziad Rahbani, on July 26, 2025, at age 69 from complications of chronic illnesses including liver issues and a reported heart attack. Ziad, born January 1, 1956, had collaborated extensively with Fairuz earlier in her career but pursued independent satirical works critiquing Lebanese society. Fairuz, then 90, made her first verified public appearance in over a decade at his funeral on July 28, 2025, in Bikfaya's Greek Orthodox church north of Beirut, arriving somberly with family including daughter Rima Rahbani to receive condolences amid hundreds of mourners. The procession drew political figures, artists, and fans across sects, highlighting Ziad's cultural impact, yet Fairuz remained silent and withdrawn, consistent with her apolitical public persona and lack of statements on contemporary conflicts. Medical teams reportedly attended her home post-announcement, reflecting the personal toll.[47][48][49][50][51] Tributes intensified around her 90th birthday, with international media and Arab press lauding her as Lebanon's unifying voice amid ongoing instability, including the 2024-2025 escalations in border conflicts. Proposals emerged for a Beirut museum honoring her legacy, yet no new artistic output materialized, reinforcing her seclusion as a function of health and familial priorities rather than external pressures. No records indicate political endorsements or engagements from Fairuz during this era, preserving her historical stance of artistic detachment.[46][52]Artistic Output

Theatrical Musicals and Collaborations

Fairuz's most prominent theatrical work emerged from her longstanding collaboration with the Rahbani brothers, Assi and Mansour, who authored librettos and composed music for approximately 20 musical plays featuring her in lead roles from the late 1950s through the 1970s.[53][54] These productions combined scripted narratives, songs, and ensemble performances, often incorporating traditional Lebanese elements like dabkeh folk dances and rural motifs with structured orchestration that drew on Western influences for dramatic effect.[53][54] Early examples include the 1957 premiere of Ayyam al-Hasad (Days of Harvest), which marked Fairuz's debut live stage appearance before a public audience.[55] Between 1960 and 1965, the Rahbanis produced at least six such musicals, focusing on Lebanese folklore and village life themes without overt political messaging.[54] Productions like The Moon Bridge, an initial Rahbani effort, achieved broad appeal through historical narratives set in Lebanese contexts.[56] These musicals were staged at major venues, including the Baalbek International Festival, where the Rahbani troupe—comprising Fairuz, supporting singers, dancers, and musicians—performed extended plays that blended Levantine musical scales with symphonic arrangements.[53][56] The collaborative process relied on the brothers' dual roles as writers and composers, tailoring roles to Fairuz's vocal range while embedding authentic regional dialects and instrumentation, such as the oud and qanun, into modern theatrical formats.[54] Later works in the 1960s and 1970s occasionally incorporated subtle commentaries on social dynamics or conflict, though the core emphasis remained on cultural preservation and narrative storytelling.[56][57]Film and Television Roles

Fairuz's cinematic output was confined to three Lebanese-Egyptian co-productions in the mid-1960s, each featuring her in roles that prioritized vocal performances over substantive acting demands, reflecting her reluctance to pursue screen careers amid a burgeoning stage and recording dominance. In Biya' el-Khawatim (The Ring Peddler, 1965), directed by Youssef Chahine, she portrayed a nomadic seller whose storyline revolved around musical interludes, with the film grossing modestly in Arab markets but amplifying her songs' reach through theatrical distribution. This was followed by Safar Barlek (Your Trip to Paris, 1966), where her character integrated folk-inspired numbers into a comedic travel narrative, though critical reception noted the plot's subordination to her singing sequences. Her final film, Bint el-Haras (The Guard's Daughter, 1968), directed by Youssef Chahine, depicted a resilient village girl amid rural strife, again leveraging Fairuz's voice for emotional peaks; the production, filmed in Lebanon, achieved commercial viability by tying into her live concert appeal but underscored her aversion to prolonged shoots, as evidenced by no subsequent features despite offers.[58] These roles, produced during peak Rahbani collaborations, generated ancillary revenue—estimated to have spurred regional record sales by 10-20% post-release through soundtrack synergies—but remained peripheral to her oeuvre, with Fairuz citing stage authenticity as preferable to scripted visuals in rare interviews.[59] Television engagements were even sparser, limited to musical specials and adaptations broadcast on Lebanese state channels during holidays or festivals, often repurposing theatrical material to capitalize on her icon status without demanding new commitments. Notable examples include Al Mahatta (The Station, 1973), a telecast blending songs with narrative sketches, and Mays al-Reem (1975), a festive program featuring ensemble performances that aired to high viewership in the Arab world.[60] The 1977-1978 musical Petra, while originating as a Rahbani stage production about ancient Jordanian lore, received limited TV adaptations in Lebanon, emphasizing choral and solo tracks over plot depth, with broadcasts confined to special events due to production constraints and her preference for auditory media.[61] Overall, screen work comprised under 5% of her output, serving promotional functions that indirectly elevated live ticket sales and discography circulation rather than establishing her as a versatile performer.[62]Personal Life

Marriage, Children, and Family Dynamics

Fairuz married Assi Rahbani, a composer and producer, on January 23, 1955.[8] The couple had four children: Ziad Rahbani (January 1, 1956 – July 26, 2025), who pursued a career as a composer, playwright, and pianist; Hali Rahbani (born 1958); Rima Rahbani (born 1965); and Layal Rahbani (1960–1988).[24][63][50] Assi Rahbani co-produced Fairuz's musicals and recordings with his brother Mansour until suffering a stroke in September 1972, after which Ziad Rahbani, then 17, began contributing arrangements and compositions to family projects.[64] By 1979, Fairuz and Assi had separated artistically, with Fairuz shifting primary collaboration to Ziad.[38] Assi died on June 21, 1986, from a cerebral hemorrhage following a coma.[63] Following Assi's death, Fairuz maintained close professional ties with Ziad, who handled composition and production for her subsequent works, including albums and stage productions.[38] The Rahbani family established a multi-generational musical lineage, with Assi and Mansour's foundational collaborations extending through Ziad's innovations and joint performances involving Fairuz, Mansour, and Ziad as late as 1998.[24] This dynasty emphasized empirical creative partnerships, producing theatrical works and recordings that integrated family roles in lyrics, music, and direction across decades.[24]Health Challenges and Public Withdrawal

Assi Rahbani, Fairuz's husband and longtime musical collaborator, suffered a debilitating stroke in 1973, which curtailed their joint productions and shifted her work toward her son Ziad Rahbani as Assi's health declined amid Lebanon's civil war.[65] Assi remained in poor health until his death on June 21, 1986, at age 63, an event that prompted a temporary ceasefire in Beirut hostilities due to the family's cultural prominence.[24] Their daughter Layal had predeceased him, dying in 1987 at age 25 from a brain stroke, compounding familial medical burdens that indirectly influenced Fairuz's creative output and public engagements.[63] Fairuz herself has faced no publicly documented major illnesses beyond age-related vocal limitations, but her progressive seclusion intensified post-1980s, with no live performances after her final concert on August 31, 2012, at Jounieh's Platea Theater.[50] By 2025, at age 90, she maintains near-total privacy, exemplified by her absence from public appeals following the August 4, 2020, Beirut port explosion—despite private meetings like one with French President Emmanuel Macron—opting instead for silence on contemporary crises.[66] This withdrawal aligns with a deliberate prioritization of seclusion over media or political commentary, limiting appearances to exceptional family events.Political Engagements and Disputes

Claims of Apolitical Stance

Fairuz has consistently avoided direct political endorsements or affiliations throughout her seven-decade career, positioning herself as a neutral cultural figure amid Lebanon's sectarian tensions. She has refrained from public statements on partisan matters and granted few interviews, thereby cultivating an image detached from electoral or ideological camps.[67][68] This apolitical posture received explicit support from political leaders, such as Progressive Socialist Party head Walid Jumblatt, who in December 2013 called for shielding Fairuz from controversy, affirming her status as a transcendent symbol of Lebanese national heritage beyond any camp's classification.[69][70] Jumblatt's intervention underscored a broader consensus among elites to preserve her neutrality, reflecting her deliberate non-engagement as a stabilizing force in a polarized society. Her oeuvre reinforces this stance through non-sectarian lyrical content focused on shared Lebanese identity, rural simplicity, and unity—elements evident in analyses of tracks evoking a cohesive homeland over factional divides.[71][72] This thematic choice aligns with a pragmatic strategy to navigate Lebanon's confessional politics, where music's universal appeal circumvents endorsement risks, as corroborated by scholarly examinations of her Rahbani-era compositions prioritizing collective harmony.[12][73] Nevertheless, empirical instances of performances in venues associated with specific factions have fostered perceptions of implicit leanings, undermining claims of absolute detachment despite the absence of overt advocacy. Such associations highlight the challenges of true apolitical insulation in Lebanon's intertwined cultural-political sphere, where context inevitably colors interpretation.[67][68]2008 Damascus Concert Backlash

Fairuz performed in Damascus on January 28, 2008, marking her first concert in Syria in over three decades, at the Damascus International Exhibition Center before a sell-out audience amid heightened regional tensions.[6][74] The event, organized under the Bashar al-Assad regime, coincided with the arrest of prominent Syrian democracy advocate Riad Seif, amplifying perceptions among critics that the performance inadvertently bolstered authoritarian legitimacy.[74] Syrian opposition figures and exiles condemned the concert as a tacit endorsement of the regime's crackdowns on dissent, arguing it normalized Syria's interference in Lebanese affairs, including alleged involvement in political assassinations like that of Rafik Hariri in 2005.[75][76] Lebanese anti-Syrian politicians and activists, viewing Damascus as "enemy territory," urged a boycott and decried the appearance as undermining efforts to hold Syria accountable for cross-border meddling, with some fans splitting over whether it compromised Fairuz's storied image of national resilience.[75][76] These dissident voices, often marginalized in regime-controlled narratives, highlighted the event's timing as emblematic of broader risks in artists engaging politically repressive states without reciprocity for human rights concerns. Defenders, including Fairuz's former collaborator Mansour Rahbani, framed the concert as an apolitical gesture of cultural exchange and peace between Lebanon and Syria, emphasizing artistic autonomy over geopolitical disputes.[75] Fairuz proceeded undeterred by the protests, performing a repertoire of her classics that drew emotional acclaim from attendees, though the backlash underscored the perils of such engagements.[6] In the aftermath, Fairuz undertook no further performances in Syria, reflecting the enduring fallout from the episode amid escalating Syrian repression and the 2011 uprising, which rendered future visits untenable and validated opposition warnings about the diplomatic and reputational costs of regime proximity.[74][76]Alleged Sympathies and Family Statements on Hezbollah

In December 2013, Ziad Rahbani, Fairuz's son and a composer known for his leftist political views, stated in an interview with Al-Ahed, a Hezbollah-affiliated outlet, that his mother "loves" Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary-general of Hezbollah.[77] [7] Rahbani, who has publicly expressed support for Hezbollah, made the remark when asked about Fairuz's political inclinations, framing it as personal affection rather than formal endorsement.[78] [79] The statement provoked immediate backlash on platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, where Lebanese users across sectarian lines decried the politicization of Fairuz, a figure long viewed as a national unifier above factionalism.[77] Critics, including right-leaning commentators, linked the claim to broader accusations of Iranian influence through Hezbollah's dominance in Lebanese Shiite politics, especially amid the group's role in the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah War and its Syrian interventions.[78] [80] Progressive leader Walid Jumblatt intervened, urging in a public statement that Fairuz be shielded from such disputes to preserve her apolitical legacy.[69] Fairuz issued no direct response, maintaining her characteristic silence on contemporary politics, while Rahbani doubled down in a subsequent Al-Mayadeen TV interview, asserting that detractors of either Fairuz or Nasrallah would face consequences and emphasizing Nasrallah's role in Lebanese resistance narratives.[69] [78] No verifiable evidence of Fairuz's personal endorsements of Hezbollah exists in public records, though perceptions persist due to Rahbani's overt sympathies and the Rahbani family's historical leftist orientations within Lebanon's polarized sectarian landscape.[7] [79]Palestine Advocacy: Supporters and Detractors

Fairuz's songs, notably "Zahrat al-Mada'in" released in 1967 shortly after the Six-Day War, evoked longing for Jerusalem and solidarity with Palestinians, portraying the city as a symbol of Arab heritage and resistance.[81][82] This track, along with earlier works like "Sanarga Yoman" from 1955, aligned with pan-Arab sentiments and earned her recognition, including Jordan's Medal of Honour awarded by King Hussein in 1963 for contributions to Arab cultural unity.[4] Supporters, particularly among left-leaning Arab nationalists and Palestinian advocates, hail these compositions as a unifying cultural bulwark, fostering emotional resilience and diaspora identification with the cause amid territorial losses.[83] Detractors, often from right-leaning Lebanese circles wary of pan-Arab overreach, contend that Fairuz's lyrics romanticized Palestinian return and Arab solidarity without reckoning with causal drivers of conflict, such as the Palestine Liberation Organization's (PLO) armed operations from Jordan in 1970—triggering Black September—and its subsequent basing in Lebanon, which escalated into the 1975 civil war by drawing Israeli incursions and sectarian strife.[82] Post-1967 critiques amplified this view, arguing her advocacy perpetuated illusions of effortless unity despite the Arab states' coordinated military defeat, which exposed pan-Arabism's structural frailties like interstate rivalries and mismatched capabilities, rendering cultural appeals inefficacious for territorial gains.[82] Empirically, while Fairuz's Palestine-themed songs amplified expatriate engagement—sustaining playback and communal rituals into the 21st century—they yielded no measurable shifts in conflict dynamics, such as halting Israeli advances or unifying Arab responses, and instead mirrored broader pan-Arab disillusionment evident in declining ideological cohesion after 1967.[83][82] Her work's entanglement in later divisions, including Palestinian factions' opposing stances during the 2011 Syrian uprising, underscores how such advocacy, though morale-boosting, often reinforced zero-sum narratives over pragmatic resolutions.[82]Reception and Legacy

Awards, Honors, and Commercial Success

Fairuz received the Medal of Honor from King Hussein of Jordan in 1963, recognizing her early contributions to Arab music.[13] In 1975, she was awarded the Gold Medal of Honor by the same monarch, further affirming her regional stature.[84] Lebanon honored her with the Order of the Cedars at Knight rank in 1962, one of the nation's highest distinctions for artists.[4] France bestowed the Honor for Arts and Letters at Commodore rank, while Tunisia granted the Highest Artistic Distinction in 1997 under President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.[4] At age 78, she was officially designated Ambassador of Arab Culture, a title reflecting her enduring symbolic role.[29] Her commercial achievements underscore this acclaim, with estimates placing her lifetime record sales above 100 million units across singles, albums, and compilations, sustained by consistent demand in the Arab world and diaspora markets.[5] She has released over 80 albums and recorded nearly 1,500 songs, contributing to her status as one of the highest-selling Middle Eastern artists.[85] Concert milestones include headlining the Olympia in London in 1994, attracting over 6,000 attendees at age 60, which demonstrated her draw beyond regional audiences.[5] Such performances, alongside releases spanning six decades, link her honors to verifiable market longevity rather than transient popularity.Cultural Influence in Lebanon and Arab World

Fairuz's music has served as a cultural anchor in Lebanon, evoking the pre-1975 civil war period of relative cosmopolitanism and cross-sectarian coexistence, where her songs were commonly played in taxis, cafes, and weddings across Christian, Muslim, and Druze communities, transcending religious divides through shared auditory familiarity.[12][73] This ubiquity helped cultivate a collective Lebanese identity rooted in nostalgia for Beirut's golden age, though empirical evidence attributes her unifying effect more to emotional resonance than to causal reduction of sectarian tensions, as Lebanon's confessional power-sharing system persisted despite her popularity.[72] During the 1980s civil war exile waves, her recordings sustained diaspora communities in Europe and the Americas, reinforcing homeland ties via cassette tapes and radio, with studies documenting her role in identity preservation among displaced Arabs.[86] Across the broader Arab world, Fairuz's influence spread primarily through radio broadcasts, where for decades many stations initiated morning programming with her tracks, amplifying Lebanon's soft power as a cultural exporter amid regional authoritarianism and limited media pluralism.[87][18] This propagation embedded her voice in daily life from Morocco to the Gulf, yet her Western penetration remained marginal, with recognition confined to niche audiences despite occasional tours, underscoring a regional rather than global breakthrough.[87] Quantifiable metrics reinforce her stature: a 2018 Forbes Middle East ranking of top regional stars placed her first, and she continues charting on Billboard's Arabic Artist 100, reflecting sustained streaming and sales dominance.[88][89] While often idealized as a pan-Arab unifier, analyses highlight how her idyllic, pastoral themes—prevalent in Rahbani Brothers compositions—provided auditory escapism, offering solace in conflict zones but potentially reinforcing passive nostalgia over impetus for sociopolitical reform, as her oeuvre rarely engaged structural critiques beyond evocative longing.[90][91] This dynamic, evident in diaspora consumption patterns, sustained cultural continuity without documented shifts in reform advocacy, tempering narratives of transformative agency.[86]Artistic Praises and Critiques

Fairuz's vocal technique has received widespread acclaim for its flexibility, enabling intricate ornaments and precise control over pitch and intonation characteristic of Arab musical traditions.[18] Ethnomusicologist Virginia Danielson highlighted the clarity and airiness of her timbre, attributing it to effective use of head resonance, which contributes to her enduring emotional depth.[92] Western reviewers have similarly praised her ability to convey profound sentiment through a pure, resonant delivery that transcends linguistic barriers.[92] Her artistic partnership with the Rahbani brothers pioneered a fusion of Levantine folk elements with Western European influences, including orchestral arrangements and melodic structures, resulting in innovative compositions that elevated Lebanese music on the Arab stage.[15] This synthesis created timeless works blending traditional tarab with modern orchestration, as noted by musicians who credit the trio for expanding expressive possibilities in regional music.[27] Critiques of Fairuz's oeuvre often center on the exclusive collaboration with the Rahbanis, which some musicologists argue constrained experimentation by favoring meticulously pre-composed songs over the improvisational spontaneity prevalent in classical Arab performances.[27] Arrangements in certain tracks have been described as occasionally slushy or uninspired in their Western borrowings, such as cocktail-lounge jazz elements, though her voice consistently compensates for these shortcomings.[93] Purists have occasionally viewed the formulaic precision of her catalog as limiting evolution in style, particularly in later phases where shifts toward her son Ziad Rahbani's more cynical narratives diverged from the earlier pastoral purity.[94]Political Legacy: Unifying Symbol or Divisive Figure?