Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Family Computer Network System

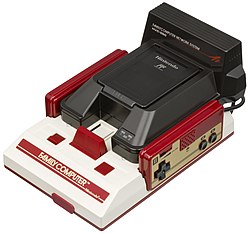

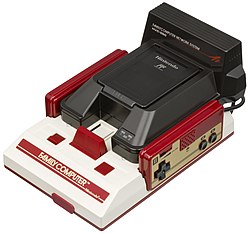

View on Wikipedia Famicom with modem | |

| Developer | Nintendo |

|---|---|

| Type | modem peripheral |

| Generation | Third generation |

| Released |

|

| Lifespan | 3 years |

| Discontinued |

|

| Units shipped | 130,000[1] |

| Removable storage | ROM card |

| Controller input | Famicom controller with numeric keypad |

| Connectivity | Dial-up modem |

| Online services | Nomura Securities |

| Best-selling game | Betting on horse racing |

| Predecessor | Cartridge, Disk Fax kiosks |

| Successor | Satellaview |

| Related | 64DD |

The Family Computer Network System (Japanese: ファミリーコンピュータ ネットワークシステム, Hepburn: Famirī Konpyūta Nettowāku Shisutemu), also known as the Famicom Net System and Famicom Modem, is a peripheral for Nintendo's Family Computer video game console, and was released in September 1988 only in Japan. Predating the modern Internet, its proprietary dial-up information service accessed live stock trades, video game cheats, jokes, weather forecasts, betting on horse racing, and a small amount of downloadable content.[1] The device uses a ROM card storage format, reminiscent to the HuCard for the TurboGrafx-16 and the Sega Card for the Master System.[2][3]

Nintendo gained experience with this endeavor which led directly to its satellite based Satellaview network for the Super Famicom in the early 1990s.

History

[edit]Development

[edit]In 1986, Nintendo's entry into basic online communications was the Disk Fax kiosks, preannouncing the deployment of 10,000 kiosks throughout Japan's toy and hobby stores within the following year. This allowed Famicom players with Famicom Disk System games to bring their writable Disk Cards into stores and upload their high scores to the company's central leaderboards via fax, enter nationwide achievement contests, and download new games cheaper than on cartridge.[4]: 75–76 [5][6][7][8]

By 1987, Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi foresaw the impending Information Age, developing a vision for transforming Nintendo beyond a toy company and into a communications company. He wanted to leverage Famicom's established and totally unique presence in one third of all of Japan's homes, to bring Nintendo into the much larger and virtually limitless communications industry and thus presumptively on par with Japan's largest company and national telephone service provider, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT). He believed the Famicom should become an appliance of the future, as pervasive as the telephone itself.[4]: 76–78 Beginning in mid-1987, he requested the exploration of a partnership with the Nomura Securities financial company, to create an information network service in Japan based on the Famicom. Led by Famicom's designer Masayuki Uemura, Nintendo Research & Development 2 developed the modem hardware; and Nomura Securities developed the client and server software and the information database. Uemura cautioned that they "weren't confident that they would be able to make network games entertaining". Five unreleased prototypes of network-enabled games were developed for the system, including Yamauchi's favorite ancient Japanese board game, Go.[1]

Production

[edit]

The Famicom Modem began mass production in September 1988. The accompanying proprietary online service called the Famicom Network System was soon launched the same year alongside Nippon Telegraph and Telephone's new DDX-TP telephone gateway for its existing packet switched network. NTT's launch initially suffered reliability problems that were painstakingly assessed by Nintendo at individual users' homes and traced back to the network.[1][4]: 78

Yamauchi said in Nintendo's 1988 corporate report that this system would "link Nintendo households to create a communications network that provides users with new forms of recreation, and a new means of accessing information". Yamauchi said to employees that the company's new purpose in addition to games was now "to provide information that can be efficiently used in each household".[4]: 76

By 1989, Nintendo had become Japan's number one company and Yamauchi wanted to position the Famicom as the key portal to a previously inconceivably large-scale potential future network of freely accessible and vital information in all aspects of daily life. Anticipating a new economy of service fees and sales commissions, he imagined Nintendo's future as the gatekeeper of expanded online shopping, with airline tickets and constant information feeds of news and movie reviews. With "intense personal commitment", he approved a multimillion-dollar advertising budget for online services, personally met with representatives in the financial industry, and successfully signed up the Daiwa and Nikko stock brokerages as service providers.[4]: 77–78 In June 1989, Nintendo of America's vice president of marketing Peter Main, said of the Japanese market that the six-year-old Famicom was present in 37% of Japan's households and that the Famicom Network System had been supporting video games and stock trading applications for some time in Japan.[9] New services included buying stamps online from the postal service, betting on horse racing, the Super Mario Club for game reviews, and the Bridgestone Tire Company using a Famicom online fitness program for its employees.[4]: 78

By 1991, all these Famicom Network System online services had shut down, except for the Super Mario Club as the sole final application of the Famicom Modem and Network System. Super Mario Club had been formed for toy shops, where the Famicom was deployed as a networked kiosk, serving consumers with a member-store-created searchable online database of Famicom game reviews. Nintendo performed market research by analyzing users' search behaviors, and directly receiving user feedback messages.[1]

In that year, the disappointed but steadfast Yamauchi stated, "It is just a matter of time. When the people are ready for it, we have the Network in place."[4]: 78

Reception

[edit]

Nintendo shipped a lifetime total of 130,000 Famicom Modems and the Famicom Network System had 15,000-20,000 users for stock brokering services, 14,000 for banking, and 3,000 businesses for Super Mario Club.[4]: 78 Even after the resolution of stability problems with the NTT's network launch, the Famicom Network System's market presence was considered "weak" for its whole lifetime for various reasons: product usability; competition from personal computers and other appliances; and the difficult nature of early adoption by the technologically unsavvy financial customer. Many found it just as easy to do transactions by traditional means, and the total home networking market was very small because people didn't want to rewire their house for their television or to have their telephone line occupied.[1][4]: 78 Uemura stated that the system's most popular application was ultimately home-based betting on horse racing, with a peak of 100,000 Famicom Modem units used and capturing 35% of Japan's fanatical online horse betting market even among diverse competition from PCs and from dedicated horse betting network terminal appliances.[1]

Legacy

[edit]Wanting to replicate and expand upon the progress seen with the Famicom Modem in Japan, Nintendo of America began a series of open announcements in mid-1989 to describe its private talks with AT&T over the prospect of launching an information network service in America in 1990.[9] The plans never materialized.

A modem for NES was tested in the United States by the Minnesota State Lottery. It would have allowed players to buy scratchcards and play the lottery with their NES at home. It was not released in the United States because some parents and legislators voiced concern that minors might learn to play the lottery illegally and anonymously, regardless of assurances from Nintendo to the contrary.[10] Internet-based gambling was banned in Minnesota.[11]

Online content would later be delivered to Nintendo's customers via the Super Famicom's Satellaview peripheral. Masayuki Uemura, lead designer of the Famicom Modem at Nintendo Research & Development 2, said: "Our experiences with the Famicom Modem triggered Nintendo's entrance into the satellite data broadcasting market in April, 1995".[1]

See also

[edit]- 64DD's Japan-based dialup Internet service called Randnet, from December 1999 to February 2001

- Nintendo Entertainment System's Teleplay Modem

- Famicom Disk System

- Atari 2600's GameLine

- Intellivision's PlayCable

- Sega Genesis's Sega Channel

- XBAND

- Super Famicom's Satellaview

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Takano, Masaharu (September 11, 1995). "How the Famicom Modem was Born". Nikkei Electronics (in Japanese).

- ^ "ファミコンの周辺機器が大集合! ザ☆周辺機器ズ 11" [A large collection of Famicom peripherals!]. Ne.jp. Archived from the original on 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2014-06-14.

- ^ "Wi-Fiコネクションについて講演 『ウイイレ』など40タイトルが開発中 - ファミ通.com" [Lecture on Wi-Fi connection 40 titles under development, including 'Wi-Re']. Famitsu. 2006-03-25. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sheff, David (1994). Game Over: How Nintendo conquered the world (1st Vintage books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780307800749. OCLC 780180879. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ McFerran, Damien (November 20, 2010). "Slipped Disk - The History of the Famicom Disk System". Nintendo Life. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ Linneman, John (July 27, 2019). "Revisiting the Famicom Disk System: mass storage on console in 1986". Eurogamer. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ "Famicom Disk System (FDS)". Famicom World. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ Eisenbeis, Richard (June 1, 2012). "Why You Can't Rent Games in Japan". Kotaku. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Freitag, Michael (June 8, 1989). "Talking Deals; How Nintendo Can Help A.T.&T". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Shapiro, Eben (1991-09-27). "Nintendo and Minnesota Set A Living-Room Lottery Test". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- ^ "Minnesota Gambling and Criminal Defense". Retrieved February 7, 2015.

External links

[edit]Family Computer Network System

View on GrokipediaDevelopment

Conception and Partnerships

In the mid-1980s, Nintendo sought to evolve the Family Computer (Famicom) platform beyond standalone cartridge games by integrating dial-up networking capabilities over telephone lines, aiming to deliver real-time services such as financial transactions, news updates, and downloadable content to Japanese households.[5] This initiative reflected broader industry trends toward digital connectivity, drawing inspiration from early personal computer services while capitalizing on the Famicom's widespread adoption since its 1983 launch.[4] The project's hardware development was handled internally by Nintendo's Research and Development 2 (R&D2) division, led by Masayuki Uemura, the original Famicom designer, focusing on a cartridge-slot modem compatible with existing consoles.[5] Key partnerships formed to realize non-gaming applications, with joint development of the modem and initial services commencing in the summer of 1987 alongside Nomura Securities, Japan's largest brokerage firm at the time, to enable stock trading and related financial features.[6] Nomura's involvement provided expertise in secure transaction protocols and market data integration, addressing the need for reliable backend infrastructure tied to Japan's telephone network operated by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT).[3] Prototyping emphasized urban reliability testing in areas with stable phone lines, culminating in the system's commercial readiness by late 1988, though early demos highlighted banking and betting utilities to demonstrate practical utility beyond entertainment.[4] These collaborations underscored Nintendo's strategy to position the Famicom as a multifunctional home terminal, though limited by the era's analog dial-up constraints and regulatory hurdles for financial data transmission.[6]Design and Production

The Family Computer Network System was engineered as a compact modem peripheral that connects directly to the Famicom console via its cartridge slot, enabling access to the system's address and data buses for integrated operation.[7] This design choice allowed the device to leverage the Famicom's existing 6502-compatible CPU for primary processing while incorporating an internal CPU dedicated to managing dial-up connections and protocol handling, reducing latency in network tasks.[7] The hardware includes the RF5C66 chip, which serves as the primary memory mapper, interfacing with CPU address lines (bits 0-7 and 12-14), generating interrupts, and delegating registers for Famicom-specific functions at addresses like $40D0.[8] A secondary zero-insertion-force (ZIF) slot accommodates proprietary ROM cards for service-specific software, ensuring modular compatibility without altering the core Famicom architecture.[7] To address the limitations of 1980s analog telephone lines, the modem was optimized for 1200 baud speeds, with engineering focused on signal modulation stability and error correction to mitigate noise-induced dropouts common in early dial-up environments.[8] Compatibility testing emphasized seamless integration with Famicom hardware variants, including the original model (HVC-001), AV Famicom (HVC-101), and Twin Famicom, verifying bus timing, power draw, and IRQ handling to prevent conflicts during connection establishment or data transfer.[9] These phases also involved validating ROM card functionality across the Famicom's PPU and CPU pipelines, ensuring that network overlays did not disrupt standard game execution when cards were absent.[8] Nintendo oversaw production in Japan starting in September 1988, manufacturing the units exclusively for domestic rollout due to the reliance on widespread NTT telephone infrastructure incompatible with international standards at the time.[3] Approximately 130,000 units were produced before discontinuation, reflecting constrained output tied to service partnerships and hardware complexity rather than broad scalability. Preparations included supply chain coordination for custom components like the RF5C66 and modem circuitry, with final assembly emphasizing reliability for consumer phone line variability to support initial service trials.[7]Initial Launch

The Family Computer Network System, a dial-up modem peripheral for the Famicom console, was released exclusively in Japan on September 1, 1988.[2] This launch introduced capabilities for connecting the console to external services via standard home telephone lines, marking Nintendo's early foray into networked gaming hardware.[10] Marketed under names including Famicom Net System, the device was promoted as a way to future-proof the Famicom by enabling access to downloadable games, news feeds, weather reports, and specialized utilities such as horse race betting.[9] Initial offerings bundled connectivity to a proprietary online platform, requiring users to enroll in a subscription-based service for full functionality.[11] Promotion targeted tech-savvy consumers in urban regions where reliable NTT telephone infrastructure supported dial-up connections without widespread compatibility issues. Early rollout emphasized partnerships, such as with Nomura Securities for financial applications like stock trading via the Famicom Trader software, showcased in contemporary advertisements.[12] However, adoption faced barriers including the added costs of the hardware—priced around 25,000 yen—and ongoing service fees, limiting appeal amid the console's established offline ecosystem.[2]Technical Specifications

Hardware Architecture

The Family Computer Network System (FNS) main unit functions as a cartridge-form-factor modem peripheral that inserts directly into the Famicom console's 60-pin cartridge slot, leveraging the system's expansion bus for signal routing including CPU read/write operations and data lines.[7] This integration enables connectivity without modifying the Famicom's video output or PPU signals, maintaining standard 8-bit era data transfer capabilities through hardware UART support ranging from 300 to 9600 baud.[7] The unit draws power solely from the console's +5V supply across multiple pins, eliminating the need for external adapters.[7] Core computational components include the RF5C66 custom mapper chip (Ricoh, QFP-100 package), which manages memory mapping, modem interfacing, and an unimplemented disk drive controller, with registers accessible at 40CF and a 21.47727 MHz crystal for timing.[7] Complementing this is the RF5A18 chip (Ricoh, QFP-100 package), housing a 65C02-compatible CPU clocked at 2.4576 MHz (derived from a 19.6608 MHz crystal divided by 8), integrated 4kB firmware ROM, 8kB internal RAM, and registers at 40D7 for secondary processing tasks.[7] A real-time clock mechanism is provided via the RF5C66's periodic high pulse (every approximately 12.5 seconds) on a dedicated pin, enabling timekeeping without external batteries.[7] Memory architecture features 8kB of work RAM (W-RAM) for general use, 16 KiB of CHR RAM across two 8kB chips for graphics buffering, and a 256kB Kanji ROM (LH5323M1 chip) mapped at 5FFF for handling Japanese character rendering.[7] The modem module incorporates an Oki MSM6827L chip for dial-up operations and a MC14LC5436P dual tone receiver for signal detection, connected via a standard Japanese RJ-11 telephone jack without provisions for international adapters.[7] Security elements include the 8633 CIC key chip for system authentication and the 8634A CIC lock for tsuushin card verification.[7] The unit exposes an internal expansion bus (P3 connector) for routing Famicom signals, supporting additional peripherals, and includes a 42-pin ZIF connector (P2) for inserting tsuushin communication cartridges, which utilize MMC1-style mapping for ROM access at FFFF.[7] Audio expansion channels are routed through the modem module, preserving compatibility with the console's sound hardware.[7]Networking and Software Protocols

The Famicom Network System utilized a dial-up modem based on the Oki MSM6827L chip for connectivity over analog telephone lines, employing UART for serial data transmission at baud rates ranging from 300 to 9600 bps, with support for both DTMF tone and pulse dialing at 10 or 20 pulses per second.[7] This setup connected to Nintendo's central servers via Japan's DDX-TP packet-switched public data network, enabling asynchronous data exchange without reliance on emerging internet standards like TCP/IP.[7] Software protocols were orchestrated by an embedded 65C02 processor operating at 2.4576 MHz within the RF5A18 firmware controller, which included a 4 kB ROM for modem initialization, command processing, and buffering. Data interactions occurred through memory-mapped registers ($40D0–$40D3), utilizing a set of approximately 25 binary commands—such as $00 for initiating a dial and $61 for disconnection—with payloads transmitted in 3-byte increments to form messages up to 255 bytes. Authentication began locally via a Checking IC (CIC) mechanism at register $40C0, which locked out unauthorized writes upon failure, followed by server-side verification using registered passwords during session establishment.[7] Error handling incorporated CRC-16 checksums (using polynomial $8385 and initial value $35AC) for select command sequences ($7C–$7F) to detect and retransmit corrupted packets amid line noise, though no formal encryption was implemented, reflecting the absence of such features in contemporaneous consumer dial-up systems. The protocols integrated directly with the Famicom's Ricoh 2A03 (6502-derived) CPU through the RF5C66 mapper's interrupt and buffering logic, allowing efficient polling without halting game execution, but inherent bandwidth limits—capped by modem speeds—restricted transfers to small packets of several kilobytes, precluding synchronous real-time multiplayer and favoring download-and-play or turn-based models.[7]Features and Applications

Gaming Services

The Family Computer Network System offered gaming services primarily through the Super Mario Club application, a dedicated ROM card that connected the Famicom to Nintendo's dial-up servers for retrieving entertainment-focused content. Launched in 1988 as part of the system's initial rollout, this service provided users with text-based game reviews, previews of upcoming titles, and strategy guides for existing Famicom games, displayed directly on the television screen during online sessions.[13][10] Access required a subscription to the network provider, with sessions limited by the era's analog phone line constraints, typically delivering concise updates rather than rich multimedia.[3] These features supplemented physical cartridges by offering real-time insights and hints, such as solutions for challenging levels in games like Super Mario Bros. or The Legend of Zelda, without enabling persistent downloads or modifications to game ROMs. Unlike later systems, the service lacked interactive multiplayer gameplay, turn-based modes, or leaderboards, focusing instead on passive content delivery to enhance solo play. This approach pioneered console-based digital information access but was constrained by hardware limitations, including no support for dynamic code execution via bank switching or temporary demo loading beyond informational data.[13][7] By 1991, as broader services declined, Super Mario Club remained one of the few active gaming-oriented applications until the network's full phase-out.[14]Non-Gaming Utilities

The Family Computer Network System extended the Famicom's functionality beyond gaming by enabling access to practical services via dedicated cartridges and dial-up connections to proprietary networks. A key utility was home banking through the Famicom ANSER cartridge, which interfaced with the Bank ANSER system—a nationwide electronic banking network launched in the late 1980s for automated teller services.[15] This allowed users of participating banks, including Sumitomo Bank, to check account balances, inquire about transactions, and perform basic transfers by inputting PINs via the Famicom's controller D-pad and buttons, with data displayed in text form on the TV screen.[11] Security relied on simple numeric entry without encryption, reflecting the era's nascent digital banking standards.[10] News and weather services were provided through the TV-NET protocol, leveraging NTT's packet-switched X.25 infrastructure for data delivery from central servers.[16] Content appeared as scrolling text overlays or static displays, offering real-time updates on national headlines, local forecasts, and public announcements without graphical elements due to hardware limitations.[9] Users accessed these via a base menu cartridge, with sessions billed per connection minute, emphasizing text-based efficiency over multimedia.[17] Additional non-gaming applications included financial information tools, such as stock price tickers in partnership with Nomura Securities, enabling subscribers to monitor live market data downloaded in batches.[6] Basic inter-user messaging functioned as a primitive email system, allowing text exchanges between registered households on the network, though limited by low bandwidth and lack of persistent storage.[10] These features, alongside lottery result queries and horse racing betting via JRA-PAT integration, positioned the system as an early experiment in household information appliances, blending entertainment hardware with utilitarian computing.[9][18] ![Nintendo-Famicom-Modem-Network-System-Horse-Betting.jpg][center]User Access and Requirements

Access to the Family Computer Network System necessitated a standard landline telephone connection, as the peripheral functioned as a dial-up modem interfacing with Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) services for connectivity.[9] The hardware attached directly to the cartridge slot of unmodified compatible Famicom consoles, specifically the original HVC-001 model, the HVC-101 AV Famicom, and the Twin Famicom, ensuring seamless integration without requiring console alterations.[9] [7] Service availability was geographically restricted to Japan, with practical usage confined to major urban centers supported by NTT's infrastructure, where network stability permitted reliable dial-up sessions following initial rollout challenges. Users initiated connections and navigated menus exclusively through the Famicom's standard controllers, employing the directional pad for number selection and buttons for confirmation and dialing, as the modem itself lacked an integrated numeric keypad or display.[7] Subscription to partner services, such as those facilitated through collaborations like Nomura Securities for specific applications, imposed setup and recurring fees, though exact structures varied by provider; general access entailed registration and payment for NTT-mediated sessions.[19] Account security relied on rudimentary password authentication entered via controller inputs, with no documented widespread breaches, yet the system's analog phone line transmission rendered it vulnerable to contemporary interception methods like physical tapping, absent modern encryption standards.[7]Commercial Performance

Market Rollout and Adoption

The Family Computer Network System launched in Japan on September 1, 1988, as a peripheral add-on for the Famicom console, developed in collaboration with Nomura Securities to enable dial-up services such as stock trading and horse race betting.[3] Promotional campaigns featured television advertisements highlighting integrated financial applications like Nomura's Famicom Trader software, alongside mentions in Nintendo's official magazines to target households interested in non-gaming utilities.[12] Bundles with service subscriptions were offered through Nomura branches, emphasizing convenience for affluent users during Japan's economic bubble period. Adoption remained niche, with approximately 130,000 units shipped over its lifespan from 1988 to 1991, representing a minuscule fraction of the Famicom's over 60 million units sold worldwide.[3] High per-session telephone connection fees, often exceeding several thousand yen due to dial-up metering, restricted access primarily to wealthier demographics capable of affording repeated usage.[9] Active subscriber numbers peaked below 100,000, concentrated around popular applications like horse racing betting, which drew significant but temporary engagement in 1989 amid special promotional events.[9] This limited rollout contrasted sharply with the Famicom's mass-market success, as network connectivity required additional hardware investment and ongoing costs that deterred broad household integration.[20] Usage spiked briefly for event-driven services but failed to sustain momentum, with most applications seeing under 20,000 consistent users for functions like stock brokering.[3]Economic Challenges and Criticisms

The Famicom Network System encountered significant economic barriers stemming from its reliance on dial-up telephone connections via NTT, incurring per-minute charges that accumulated rapidly during sessions for services like stock trading and horse race betting. These ongoing telephony fees, typical of Japan's 1980s infrastructure where local calls alone could exceed 10 yen per minute after initial free periods, deterred widespread consumer adoption among Famicom owners accustomed to the low marginal cost of cartridge-based gaming.[21][10] Criticisms in contemporary Japanese media highlighted the system's unreliable connections, with frequent interruptions and unstable line conditions rendering services impractical for regular use, even after initial NTT network stabilizations. The limited content library, focused predominantly on non-gaming utilities rather than exclusive video games, failed to provide compelling value beyond niche applications like lottery access, lacking the draw of robust, downloadable gaming experiences. Nintendo internally viewed the initiative as overambitious given the era's bandwidth constraints, where data transfers—such as small program loads—could take minutes to hours at 1200 baud speeds, exacerbating user frustration without offsetting the financial burden.[21][3]Comparative Analysis with Contemporaries

The Family Computer Network System (FNS), launched in July 1987, predated Sega's Mega Net service by three years, offering an earlier foray into dial-up connectivity for home consoles via its 2400 bps modem integrated with the Famicom.[22] Unlike Mega Net, which emphasized real-time online multiplayer gaming and arcade-style titles on the Mega Drive starting in April 1990, the FNS prioritized non-gaming utilities such as bank transfers and lottery access alongside limited interactive applications, reflecting Nintendo's broader vision for household information services rather than pure entertainment competition.[22] Both systems grappled with the era's dial-up infrastructure limitations, including per-minute telephone charges and sluggish data rates that deterred widespread adoption before broadband proliferation.[22] In contrast to PC-based dial-up services like CompuServe, which by the mid-1980s supported file transfers, email, and bulletin boards for versatile computing tasks on systems with expandable software ecosystems, the FNS remained tethered to the Famicom's 8-bit architecture, restricting it to proprietary Nintendo-hosted content without the open-ended programmability of personal computers.[23] CompuServe's consumer access via modems grew steadily through the 1980s, peaking with millions of subscribers by leveraging PC compatibility for productivity and hobbyist applications, whereas the FNS's console-centric design offered seamless integration for non-technical users but lacked the depth of third-party software and customization that sustained PC online communities.[23] The FNS shared failure modes with earlier U.S. console experiments, such as the 1983 GameLine modem for the Atari 2600, which enabled game downloads and basic multiplayer but collapsed commercially after attracting only a few thousand subscribers due to high access fees and unreliable service amid the 1983 video game crash.[24] GameLine's pivot by its operator, Control Video Corporation, to PC-focused networking—eventually evolving into AOL—underscored the unreadiness of console audiences for paid, phone-line-dependent online features, a challenge echoed in the FNS's limited rollout to under 20,000 units sold despite Japan's denser telephony infrastructure.[24] These parallels highlight how pre-broadband economics, including subscription costs averaging several hundred yen per session for FNS, stifled viability across platforms until the late 1990s.[25]| System | Launch Year | Primary Services | Key Limitations | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNS (Nintendo Famicom) | 1987 | Banking, lotteries, basic interactivity | Console-locked content, dial-up fees | Low adoption; service persisted until 2001 but with minimal users[25] |

| Mega Net (Sega Mega Drive) | 1990 | Online multiplayer games | High infrastructure costs, Japan-only | Discontinued within a year due to poor uptake[22] |

| GameLine (Atari 2600) | 1983 | Game downloads, multiplayer | Post-crash market, subscription model | Failed commercially; operator shifted to PCs[24] |