Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

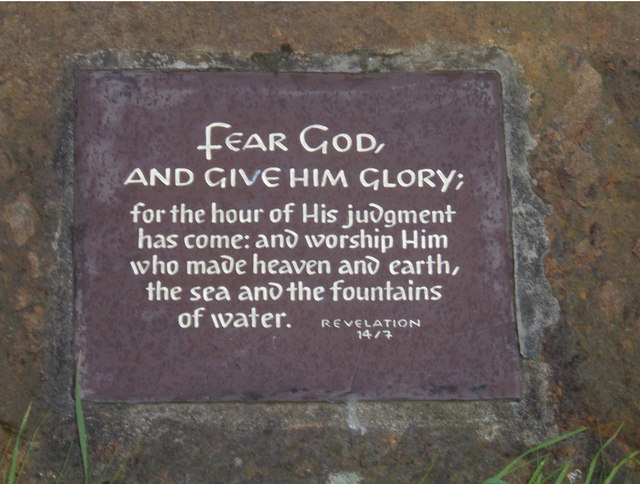

Fear of God

View on Wikipedia

Fear of God or theophobia[a] may refer to fear itself, but more often to a sense of awe, and submission to, a deity. People subscribing to popular monotheistic religions for instance, might fear Hell and divine judgment, or submit to God's omnipotence.

Judaism

[edit]The first mention of the fear of God in the Hebrew Bible is in Genesis 22:12, where Abraham is commended for putting his trust in God. In Isaiah 11:1–3, the prophet describes the shoot that shall sprout from the stump of Jesse, "The spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him: a spirit of wisdom and of understanding, A spirit of counsel and of strength, a spirit of knowledge and of fear of the Lord, and his delight shall be the fear of the Lord." Proverbs 9:10 says that "fear of the Lord" is "the beginning of wisdom".[1]

The Hebrew words יִרְאַ֣ת (yir’aṯ) and פחד (p̄aḥaḏ) are most commonly used to describe fear of God/El/Yahweh.[citation needed]

Bahya ibn Paquda characterized two types of fear as a lower "fear of punishment" and a higher "fear of [divine awe] glory." Abraham ibn Daud differentiated between "fear of harm" (analogous to fear of a snake bite or a king's punishment) and "fear of greatness," analogous to respect for an exalted person, who would do us no harm. Maimonides categorized the fear of God as a positive commandment, as the feeling of human insignificance deriving from contemplation of God's "great and wonderful actions and creations."[2][3]

Christianity

[edit]In the New Testament, this fear is described using the Greek word φόβος (phobos, 'fear/horror'), except in 1 Timothy 2:10, where Paul describes γυναιξὶν ἐπανγελλομέναις θεοσέβειαν (gynaixin epangellomenais theosebeian), "women professing the fear of God", using the word θεοσέβεια (theosebeia lit. 'god-respecting').

The term can mean fear of God's judgment. However, from a theological perspective "fear of the Lord" encompasses more than simple fear. Robert B. Strimple says, "There is the convergence of awe, reverence, adoration, honor, worship, confidence, thankfulness, love, and, yes, fear."[4] In the Magnificat (Luke 1:50) Mary declaims, "His mercy is from age to age to those who fear him." The Parable of the Unjust Judge (Luke 18:1–8) finds Jesus describing the judge as one who "...neither feared God nor cared for man." Some translations of the Bible, such as the New International Version, sometimes replace the word "fear" with "reverence".[citation needed]

According to Pope Francis, “The fear of the Lord, the gift of the Holy Spirit, doesn’t mean being afraid of God, since we know that God is our Father that always loves and forgives us,...[It] is no servile fear, but rather a joyful awareness of God’s grandeur and a grateful realization that only in him do our hearts find true peace.”[5] Roman Catholicism counts this fear as one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. In some contexts it is called wonder and awe in God's presence, such as the enumeration of the seven gifts in the Roman Rite of the sacrament of Confirmation.[6] In Proverbs 15:33, the fear of the Lord is described as the "discipline" or "instruction" of wisdom.[7] Writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia, Jacques Forget explains that this gift "fills us with a sovereign respect for God, and makes us dread, above all things, to offend Him."[8] In an April 2006 article published in Inside the Vatican magazine, contributing editor John Mallon writes that the "fear" in "fear of the Lord" is often misinterpreted as "servile fear" (the fear of getting in trouble) when it should be understood as "filial fear" (the fear of offending someone whom one loves).[9]

Lutheran theologian Rudolf Otto coined the term numinous to express the type of fear one has for God. Anglican lay theologian C. S. Lewis references the term in many of his writings, but specifically describes it in his book The Problem of Pain and states that fear of the numinous is not a fear that one feels for a tiger, or even a ghost. Rather, the fear of the numinous, as C. S. Lewis describes it, is one filled with awe, in which you "feel wonder and a certain shrinking" or "a sense of inadequacy to cope with such a visitant and our prostration before it". It is a fear that comes forth out of love for the Lord.[citation needed]

A related concept (mostly present within Catholic theology) is the 'Sin of Human Respect'. This occurs when the 'Fear of God' is replaced with a 'Fear of other people' (aiming to please other people more than God), leading to sin.[10]

Islam

[edit]Taqwa is an Islamic term for being conscious and cognizant of God, of truth, of the rational reality, "piety, fear of God".[11][12] It is often found in the Quran. Al-Muttaqin (Arabic: اَلْمُتَّقِينَ Al-Muttaqin) refers to those who practice taqwa, or in the words of Ibn Abbas, "believers who avoid shirk with Allah and who work in His obedience."[13]

Bahá'í Faith

[edit]In the Bahá'í Faith, "The heart must be sanctified from every form of selfishness and lust, for the weapons of the unitarians and the saints were and are the fear of God."[14]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The word is taken from (Greek: Θεοφοβία, romanized: Theofovía, pronounced: / ˌθɪəˈfəʊbɪə /) noun. morbid fear or hatred of God

Further reading

[edit]- Kenny, Charles (1882). . Half-Hours With The Saints and Servants of God. Burns and Oats.

- O'Reilly, Bernard (1897). . Beautiful pearls of Catholic truth. Henry Sphar & Co.

- Reeves, Michael (2021), Rejoice and Tremble: The Surprising Good News of the Fear of the Lord, Wheaton, IL.: Crossway, ISBN 978-1-4335-6532-8.

References

[edit]- ^ The New Jewish Publication Society of America Version translates the Hebrew as discipline.

- ^ "Fear of God". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Office of the Chief Rabbi Archived October 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Fear of the Lord". Opc.org. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Harris, Elise. "Pope: Fear of the Lord an alarm reminding us of what's right", Catholic News Agency, June 11, 2014

- ^

- Hughes, Kathleen (1998). "The vocation of a liturgist: a response to Cardinal Danneels". In Bernstein, Eleanor; Connell, Martin (eds.). Traditions and Transitions. 1996 Conference of the Notre Dame Center for Pastoral Liturgy. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-56854-024-5.

- "CCC, 1299". Vatican.va.

- ^ The New Revised Standard Version translates the Hebrew as instruction.

- ^ Forget, Jacques. "Holy Ghost." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 3 September 2016

- ^ Mallon, John (April 2006). "The Primacy of Jesus, the Primacy of Love". Inside the Vatican. ISSN 1068-8579. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- ^ Pope, Charles (6 June 2019). "Do You Fear the Right Thing? A Meditation on the Story of Chicken Little". Catholic Standard. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Taḳwā",Encyclopaedia of Islam (2012).

- ^ Nanji, Azim. "Islamic Ethics," in A Companion to Ethics, Peter Singer. Oxford: Blackwells, n(1991), pp. 106–118.

- ^ "The Meaning of Al-Muttaqin". Quran Tafsir Ibn Kathir. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Fear of God", Bahá'í Library Online

External links

[edit]- Jewish Encyclopedia: Fear of God

- Bauck, Whitney. "Putting the Fear of God in the Fashion Industry", Christianity Today, August 19, 2016

- The Fear of God Compilation of Christian articles and sermons