Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

First Intermediate Period of Egypt

View on WikipediaKey Information

| History of Egypt |

|---|

|

|

|

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

The First Intermediate Period, described as a 'dark period' in ancient Egyptian history,[1] spanned approximately 125 years, c. 2181–2055 BC, after the end of the Old Kingdom.[2] It comprises the Seventh (although this is mostly considered spurious by Egyptologists), Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and part of the Eleventh Dynasties. The concept of a "First Intermediate Period" was coined in 1926 by Egyptologists Georg Steindorff and Henri Frankfort.[3]

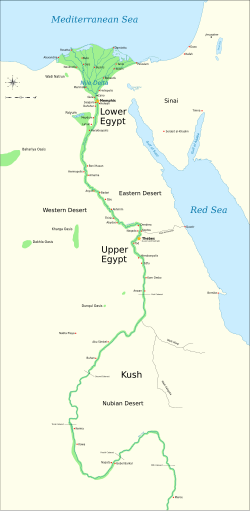

Very little monumental evidence survives from this period, especially from the beginning of the era. The First Intermediate Period was a dynamic time in which rule of Egypt was roughly equally divided between two competing power bases. One of the bases was at Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt, a city just south of the Faiyum region, and the other was at Thebes, in Upper Egypt.[4] It is believed that during that time, temples were pillaged and violated, artwork was vandalized, and the statues of kings were broken or destroyed as a result of the postulated political chaos.[5] The two kingdoms would eventually come into conflict, which would lead to the conquest of the north by the Theban kings and to the reunification of Egypt under a single ruler, Mentuhotep II, during the second part of the Eleventh Dynasty. This event marked the beginning of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

History

[edit]Events leading to the First Intermediate Period

[edit]The fall of the Old Kingdom is often described as a period of chaos and disorder by some literature in the First Intermediate Period, but mostly by the literature of successive eras of ancient Egyptian history. The causes that brought about the downfall of the Old Kingdom are numerous, but some are merely hypothetical. One reason that is often quoted is the extremely long reign of Pepi II, the last major pharaoh of the 6th Dynasty. He ruled from his childhood until he was very elderly, possibly in his 90s, but the length of his reign is uncertain. He outlived many of his anticipated heirs, thereby creating problems with succession.[6] Thus, the regime of the Old Kingdom disintegrated amidst this disorganization.[7][8] Another major problem was the rise in power of the provincial nomarchs. Towards the end of the Old Kingdom the positions of the nomarchs had become hereditary, so families often held onto the position of power in their respective provinces. As these nomarchs grew increasingly powerful and influential, they became more independent from the king.[9] They erected tombs in their own domains and often raised armies. The rise of these numerous nomarchs inevitably created conflicts between neighboring provinces, often resulting in intense rivalries and warfare between them. A third reason for the dissolution of centralized kingship that is mentioned was the low levels of the Nile inundation which may have been caused by a drier climate, resulting in lower crop yields bringing about famine across ancient Egypt;[10] see 4.2 kiloyear event. There is however no consensus on this subject. According to Manning, there is no relationship with low Nile floods. "State collapse was complicated, but unrelated to Nile flooding history."[11]

The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties at Memphis

[edit]The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties are often overlooked because very little is known about the rulers of these two periods. Manetho, a historian and priest from the Ptolemaic era, describes 70 kings who ruled for 70 days.[12] This is almost certainly an exaggeration meant to describe the disorganization of the kingship during this time period. The Seventh Dynasty may have been an oligarchy comprising powerful officials of the Sixth Dynasty based in Memphis who attempted to retain control of the country.[13] The Eighth dynasty rulers, claiming to be the descendants of the Sixth Dynasty kings, also ruled from Memphis.[14] Little is known about these two dynasties since very little textual or architectural evidence survives to describe the period. However, a few artifacts have been found, including scarabs that have been attributed to king Neferkare II of the Seventh Dynasty, as well as a green jasper cylinder of Syrian influence which has been credited to the Eighth Dynasty.[15] Also, a small pyramid believed to have been constructed by King Ibi of the Eighth Dynasty has been identified at Saqqara.[16] Several kings, such as Iytjenu, are only attested once and their position remains unknown.

Rise of the Heracleopolitan kings

[edit]Sometime after the obscure reign of the Seventh and Eighth Dynasty kings a group of rulers arose in Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt.[12] These kings comprise the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties, each with nineteen listed rulers. The Heracleopolitan kings are conjectured to have overwhelmed the weak Memphite rulers to create the Ninth Dynasty, but there is virtually no archaeology elucidating the transition, which seems to have involved a drastic reduction in population in the Nile Valley.

The founder of the Ninth Dynasty, Akhthoes or Akhtoy, is often described as an evil and violent ruler, most notably in Manetho's writing. Possibly the same as Wahkare Khety I, Akhthoes was described as a king who caused much harm to the inhabitants of Egypt, was seized with madness, and was eventually killed by a crocodile.[17] This may have been a fanciful tale, but Wahkare is listed as a king in the Turin Canon. Kheti I was succeeded by Kheti II, also known as Meryibre. Little is certain of his reign, but a few artifacts bearing his name survive. It may have been his successor, Kheti III, who would bring some degree of order to the Delta, though the power and influence of these Ninth Dynasty kings was seemingly insignificant compared to the Old Kingdom pharaohs.[18]

A distinguished line of nomarchs arose in Siut (or Asyut), a powerful and wealthy province in the south of the Heracleopolitan kingdom. These warrior princes maintained a close relationship with the kings of the Heracleopolitan royal household, as evidenced by the inscriptions in their tombs. These inscriptions provide a glimpse at the political situation that was present during their reigns. They describe the Siut nomarchs digging canals, reducing taxation, reaping rich harvests, raising cattle herds, and maintaining an army and fleet.[17] The Siut province acted as a buffer state between the northern and southern rulers, and the Siut princes would bear the brunt of the attacks from the Theban kings.

Ankhtifi

[edit]The South was dominated by warlords, the best-known of whom is Ankhtifi, whose tomb was discovered in 1928 at Mo’alla, 30 km south of Luxor. He was a nomarch or provincial governor of the nome based at Hierakonpolis, but he then expanded to the south and conquered a second nome centred on Edfu. He then tried to expand to the north to conquer the nome centred on Thebes, but was unsuccessful, as they refused to come out and fight.

His tomb is highly decorated and contains an extremely informative autobiography in which he paints a picture of Egypt riven by hunger and famine from which he, the great Ankhtifi, had rescued them. ‘I gave bread to the hungry and did not allow anyone to die’. This economic disaster is much debated by modern commentators: it seems that every ruler made similar claims. But it seems clear that for all practical purposes, Ankhtifi was the ruler and there was no higher power to whom he owed allegiance. The unity of Egypt had broken down.

Rise of the Theban kings

[edit]It has been suggested that an invasion of Upper Egypt occurred contemporaneously with the founding of the Heracleopolitan kingdom, which would establish the Theban line of kings, constituting the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties.[19] This line of kings is believed to have been descendants of Intef, who was the nomarch of Thebes, often called the "keeper of the Door of the South".[20] He is credited for organizing Upper Egypt into an independent ruling body in the south, although he himself did not appear to have tried to claim the title of king. However, his successors in the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties would later do so for him.[21] One of them, Intef II, begins the assault on the north, particularly at Abydos.

By around 2060 BC, Intef II had defeated the governor of Nekhen, allowing further expansion south, toward Elephantine. His successor, Intef III, completed the conquest of Abydos, moving into Middle Egypt against the Heracleopolitan kings.[22] The first three kings of the Eleventh Dynasty (all named Intef) were, therefore, also the last three kings of the First Intermediate Period and would be succeeded by a line of kings who were all called Mentuhotep. Mentuhotep II, also known as Nebhepetra, would eventually defeat the Heracleopolitan kings around 2033 BC and unify the country to continue the Eleventh Dynasty, bringing Egypt into the Middle Kingdom.[22]

The Ipuwer Papyrus

[edit]

The emergence of what is considered literature by modern standards seems to have occurred during the First Intermediate Period, with a flowering of new literary genres in the Middle Kingdom.[23] A particularly important piece is the Ipuwer Papyrus, often called the Lamentations or Admonitions of Ipuwer, which although not dated to this period by modern scholarship may refer to the First Intermediate Period and record a decline in international relations and a general impoverishment in Egypt.[24]

The art and architecture of the First Intermediate Period

[edit]The First Intermediate Period in Egypt was generally divided into two main geographical and political regions, one centered at Memphis and the other at Thebes. The Memphite kings, although weak in power, held on to the Memphite artistic traditions that had been in place throughout the Old Kingdom. This was a symbolic way for the weakened Memphite state to hold on to the vestiges of glory in which the Old Kingdom had reveled.[25] On the other hand, the Theban kings, physically isolated from Memphis (the capital of Egypt in the Old Kingdom) and the Memphite center of art, were forced to develop their own "Pre-Unification Theban Style" of art to fulfill their kingly duty of creating order out of chaos through art.[26]

There is not much known about the style of art from the North (centered in Heracleopolis) because not much is known about the Heracleopolitan kings: little information is provided detailing their rule on monuments from the North. However, much is known about the Pre-Unification Theban Style, as the Theban kings of the Pre-Unification Eleventh Dynasty used art to reinforce the legitimacy of their rule, and many royal workshops were created, forming a distinctive Upper Egyptian style of art different from the Old Kingdom canon.[26]

Reliefs from the Pre-Unification Theban style of art consist primarily of either high raised relief or deep sunk relief with incised details. Figures depicted have narrow shoulders and a high small of the back, with rounded limbs and a lack of musculature in males; males also sometimes are shown with rolls of fat (a characteristic that originated in the Old Kingdom to portray mature males) and have angular breasts and, while the female breast is more angular or pointed or is shown through a long gentle curve with no nipple (in other periods, the female breast is depicted as curved). Facial features characteristic of this style include a large eye, which is outlined with a band of relief meant to represent eye paint. The band meets the outer eye corner and this line usually runs back to the ear. The eyebrow above the eye is mostly flat; it does not mimic the shape of the eyelid. A deep incision is used in the creation of the broad nose, and the ear is both large and oblique.[26]

An example of Pre-Unification Theban reliefs is the Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati, a limestone stela from the reign of Mentuhotep II, ca. 2051-2030 BCE. In this stela, Maati is seated at an offering table with a jar of sacred oils in his left hand, and the text surrounding him references other figures from his life, such as the treasurer Bebi and the ancestor of the ruling Intef family, demonstrating the close bonds that tie together rulers and followers in Theban society during the First Intermediate Period.[27]

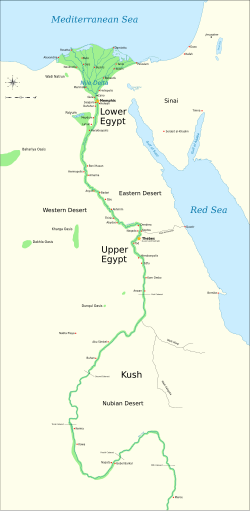

Strong facial features and the round modeling of limbs is also seen in statues, as seen in the Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery, from the 11th Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period, also under the reign of Mentuhotep II.[28]

Males with pronounced, angular breasts portrayed with rolls of fat, as well as females with angular or pointed breasts are seen in the collection of Limestone Reliefs of High Official Tjetji. The Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji contains 14 horizontal lines of text at the top of the relief, with an account of Tjetji's life. Five vertical columns on the right of the relief dictate an elaborate offering formula particular to the First Intermediate Period. Tjetji faces right with two smaller males on the left that are most likely official staff. Tjetji himself is depicted as a mature official with a pronounced breast, rolls of fat on his torso, and a calf-length kilt. The officials shown on the left are more youthful and wear shorter kilts, symbolizing that they are less mature and active.[26] The depiction of the female figure specific to the First Intermediate Period is also seen in the Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji; in the image provided, the angular breast can be seen.[26]

The building projects of the Heracleopolitan kings in the North were very limited. Only one pyramid believed to belong to King Merikare (2065–2045 BC) is mentioned to be somewhere at Saqqara. Also, private tombs that were built during the time pale in comparison to the Old Kingdom monuments, in quality and size. There are still relief scenes of servants making provisions for the deceased as well as the traditional offering scenes which mirror those of the Old Kingdom Memphite tombs. However, they are of a lower quality and are much simpler than their Old Kingdom parallels.[29] Wooden rectangular coffins were still being used, but their decorations became more elaborate during the rule of the Heracleopolitan kings. New Coffin Texts were painted on the interiors, providing spells and maps for the deceased to use in the afterlife.

Artworks that survived from the Theban Period show that the artisans took on new interpretations of traditional scenes. They employed the use of bright colors in their paintings and changed and distorted the proportions of the human figure. This distinctive style was especially evident in the rectangular slab stelae found in the tombs at Naga el-Deir.[30] In terms of royal architecture, the Theban kings of the early eleventh dynasty constructed rock cut tombs called saff tombs at El-Tarif on the west bank of the Nile. This new style of mortuary architecture consisted of a large courtyard with a rock-cut colonnade at the far wall. Rooms were carved into the walls facing the central courtyard where the deceased were buried, allowing for multiple people to be buried in one tomb.[31] The undecorated burial chambers may have been due to the lack of skilled artists in the Theban kingdom.

-

Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery

-

Limestone Stela of Tjetji

-

Limestone Stela Featuring Woman

References

[edit]- ^ Redford, Donald B. (2001). The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 526.

- ^ Kathryn A. Bard, An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 41.

- ^ Schneider, Thomas (27 August 2008). "Periodizing Egyptian History: Manetho, Convention, and Beyond". In Klaus-Peter Adam (ed.). Historiographie in der Antike. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 181–197. ISBN 978-3-11-020672-2.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan (1961) Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford University Press), 107–109.

- ^ Breasted, James Henry (1923). A History of the Ancient Egyptians. Charles Scribner's Sons, 133.

- ^ Kinnaer, Jacques. "The First Intermediate Period" (PDF). The Ancient Egypt Site. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan (1961) Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford University Press), 110.

- ^ Rothe, et al., (2008) Pharaonic Inscriptions From the Southern Eastern Desert of Egypt, Eisenbrauns

- ^ Breasted, James Henry. (1923) A History of the Ancient Egyptians Charles Scribner's Sons, 117-118.

- ^ Malek, Jaromir (1999) Egyptian Art (London: Phaidon Press Limited), 155.

- ^ Water, irrigation and their connection to State Power in Egypt (2012), p. 20; J.G. Manning, Yale University

- ^ a b Sir Alan Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), 107.

- ^ Hayes, William C. The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom, p. 136, available online

- ^ Breasted, James Henry. (1923) A History of the Ancient Egyptians Charles Scribner's Sons, 133-134.

- ^ Baikie, James (1929) A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the End of the XVIIIth Dynasty (New York: The Macmillan Company), 218.

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. (2008) An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (Malden: Blackwell Publishing), 163.

- ^ a b James Henry Breasted, Ph.D., A History of the Ancient Egyptians (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1923), 134.

- ^ Baikie, James (1929) A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the End of the XVIIIth Dynasty (New York: The Macmillan Company), 224.

- ^ Baikie, James (1929) A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the End of the XVIIIth Dynasty (New York: The Macmillan Company), 221.

- ^ Baikie, James (1929) A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the End of the XVIIIth Dynasty (New York: The Macmillan Company), 135.

- ^ Baikie, James (1929) A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the End of the XVIIIth Dynasty (New York: The Macmillan Company), 245.

- ^ a b James Henry Breasted, Ph.D., A History of the Ancient Egyptians (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1923), 136.

- ^ Kathryn A. Bard, An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 174–175.

- ^ Gregory Mumford, Tell Ras Budran (Site 345): Defining Egypt's Eastern Frontier and Mining Operations in South Sinai during the Late Old Kingdom (Early EB IV/MB I), Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 342 (May, 2006), pp. 13–67, The American Schools of Oriental Research. Article Stable URL: JSTOR 25066952

- ^ Jaromir Malek, Egyptian Art (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999), 159.

- ^ a b c d e Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 80–89. ISBN 9780674030657.

- ^ "Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "British Museum". The British Museum. 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- ^ Jaromir Malek, Egyptian Art (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999), 156.

- ^ Jaromir Malek, Egyptian Art (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999), 161.

- ^ Jaromir Malek, Egyptian Art (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999), 162.

External links

[edit]First Intermediate Period of Egypt

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context and Chronology

Collapse of the Old Kingdom

The collapse of the Old Kingdom, conventionally dated to the end of the Sixth Dynasty around 2181 BCE, marked the disintegration of centralized pharaonic authority after approximately five centuries of relative stability.[5] This period followed the extended reign of Pepi II (c. 2278–2184 BCE), estimated at up to 94 years, during which the pharaoh ascended the throne as a child and oversaw a gradual erosion of royal influence due to administrative inertia and weak succession.[6] Pepi II's successors, including Merenre II and ephemeral rulers of the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties, failed to reassert control, as evidenced by short reigns and diminished monumental construction, signaling the exhaustion of the state's resources and bureaucratic apparatus. A primary causal factor was climatic deterioration, including a megadrought around 2200 BCE that drastically reduced Nile flood levels for decades, leading to agricultural failure, famine, and demographic decline across Egypt and the Near East.[7] Geological evidence from sediment cores and speleothems indicates decreased summer monsoon precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands, curtailing the Nile's inundation and disrupting the irrigation-dependent economy that underpinned Old Kingdom prosperity.[8] This environmental stress exacerbated internal vulnerabilities, such as the decentralization of power to provincial nomarchs, who increasingly managed local resources independently, undermining Memphis's fiscal and military oversight.[9] Economic strains from sustained pyramid-building campaigns and disruptions in long-distance trade for materials like copper and myrrh further compounded the crisis, as royal expeditions waned and regional elites prioritized self-sufficiency.[10] Literary texts, such as the Admonitions of Ipuwer—a Middle Kingdom composition possibly drawing on earlier traditions—depict societal upheaval, including famine, social inversion, and violence, reflecting perceptions of chaos that align with archaeological indications of abandoned settlements and reduced elite tomb inscriptions in the late Sixth Dynasty.[11] While debates persist on the precise historicity of such accounts, empirical data from paleoclimatology and settlement patterns confirm that the interplay of aridification and administrative fragmentation precipitated the Old Kingdom's fall, paving the way for political disunity.[12]Definition and Temporal Boundaries

The First Intermediate Period denotes the interval in ancient Egyptian history characterized by the disintegration of the Old Kingdom's unified, centralized state apparatus, resulting in fragmented political authority, the empowerment of local nomarchs, and rival claims to kingship by ephemeral dynasties in the Memphite region and Heracleopolis in the north, contrasted with Theban dominance in the south. This era is distinguished from preceding and succeeding periods by the absence of monumental pyramid-building, reduced long-distance trade, and a reliance on provincial self-sufficiency amid climatic adversity and social upheaval, as evidenced by contemporary biographical inscriptions and prophetic texts lamenting disorder.[13][14] Chronologically, the period is bounded by the demise of the 6th Dynasty, conventionally placed after the protracted reign of Pepi II (c. 2278–2184 BCE) and the negligible rule of subsequent kings like Nitocris, marking the onset around 2181 BCE.[15] Its conclusion is tied to the military triumphs of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty, who subdued northern rivals and proclaimed himself ruler of a reunified Egypt by approximately 2055 BCE, initiating the Middle Kingdom.[15][16] Scholarly datings exhibit variance owing to sparse primary evidence—such as the damaged Turin King List and Manetho's later historiography—and debates over regnal overlaps, with some reconstructions favoring 2150–2030 BCE or even 2118–1980 BCE based on revised synchronisms between Upper and Lower Egyptian rulers.[17][1] These discrepancies underscore the interpretive challenges in aligning fragmentary stelae, tomb inscriptions, and Nilotic flood records absent a fixed astronomical anchor from this epoch.[18]Political Fragmentation and Conflicts

Seventh and Eighth Dynasties at Memphis

The Seventh Dynasty's existence remains debated among Egyptologists, with ancient accounts like Manetho's portraying it as an ephemeral oligarchy of seventy kings ruling Memphis for seventy days, a figure interpreted as symbolic of transitional chaos rather than historical fact.[19] [1] No contemporary inscriptions or monuments securely attest to these rulers, and the Turin Royal Canon omits a separate dynasty, suggesting the designation may stem from later scribal constructs to account for the power vacuum following the Sixth Dynasty's collapse around 2181 BC.[20] In contrast, the Eighth Dynasty is recognized as a sequence of approximately seventeen to twenty-five short-reigning kings based in Memphis, spanning roughly 2181–2125 BC, who claimed legitimacy through Old Kingdom titulary and cartouches imitating predecessors like Pepi II.[21] Key rulers, as reconstructed by Jürgen von Beckerath from king lists and sparse finds, include Neferkara I (possibly reigning 1 year), Merenhor (2 years), Neferkamin (1 year, attested by a stela), and Ibi (2 years, known from a small pyramid at Saqqara).[22] These pharaohs issued decrees, such as those for the temple of Min at Coptos under Neferkauhor, but archaeological evidence is limited to cylinder seals, private stelae, and minor inscriptions, primarily from provincial sites rather than Memphis itself.[23] The dynasties' weak hold on power is evidenced by the absence of large-scale construction or pyramid projects, unlike the Old Kingdom, signaling economic strain and the rise of autonomous nomarchs who ignored central authority.[1] By the dynasty's end, control shifted to Heracleopolitan rulers of the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties, as Memphite kings failed to quell provincial fragmentation or restore unified administration.[21] This transition underscores causal factors like prolonged Sixth Dynasty instability and resource depletion, eroding the pharaoh's divine mandate and enabling local elites to consolidate influence.Rise of Heracleopolitan Rule

Following the weakening of central authority under the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties at Memphis, circa 2160 BCE, local nomarchs in the Faiyum region capitalized on political fragmentation to claim pharaonic titles, establishing the Ninth Dynasty at Heracleopolis Magna (ancient Henesut).[24] This rise was facilitated by the hereditary entrenchment of provincial governors, who had gained autonomy during the late Old Kingdom due to administrative decentralization and weakened royal oversight after the long reign of Pepi II.[25] Heracleopolis's strategic position near the fertile Faiyum depression, with its irrigation potential, supported economic self-sufficiency and military projection into the Nile Delta and northern Middle Egypt.[24] The founding king is typically identified as Meryibre Khety (also known as Akhthoes), who is attested in Manetho's king list and later traditions as overthrowing Memphite remnants, though contemporary evidence is sparse and relies on fragmentary inscriptions and biographical texts from allied nomarchs.[25] Subsequent rulers, including Neferkare VII and possibly Wahkare Khety I, expanded influence by forging alliances with northern nomarchs, such as those at Assiut (Siut), whose tomb inscriptions describe defensive campaigns against southern incursions from Thebes.[24] These nomarchs, like Kheti III of Assiut, explicitly professed loyalty to Heracleopolitan kings, providing military support and portraying them as restorers of order amid famine and unrest documented in prophetic literature like the Instructions of Merikare.[25] Heracleopolitan rule, spanning the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties (c. 2160–2025 BCE), maintained nominal suzerainty over Lower Egypt but faced persistent rivalry with the Eleventh Dynasty at Thebes, leading to border skirmishes in Middle Egypt.[24] Kings like Merikare are credited in didactic texts with pragmatic governance, emphasizing justice and military readiness to legitimize authority, though archaeological attestation remains limited to seals, stelae, and regional tombs rather than monumental pyramids.[25] This period's power consolidation reflected causal dynamics of regionalism, where control over grain production and riverine trade routes enabled Heracleopolis to supplant Memphis without full reunification, until Mentuhotep II's conquests circa 2055 BCE.[24]Theban Ascendancy and Rivalries

The Theban ascendancy emerged in the early 11th Dynasty, with local rulers of the nome of Waset (Thebes) transitioning from provincial governors to claimants of pharaonic authority amid the Old Kingdom's collapse. Mentuhotep I, serving initially as vizier under the late 10th Dynasty, assumed royal titles around 2134–2118 BC, establishing a Theban line that consolidated power in Upper Egypt through alliances with neighboring nomarchs.[26] His rule laid the foundation for expansion, unifying territories from Elephantine to This without direct conflict records. Intef I, succeeding circa 2118–2110 BC, was the first unequivocally royal Theban ruler, extending control northward to Dendera and encompassing the first six nomes of Upper Egypt through military and diplomatic means.[27] His stelae proclaim unification of Thebes, Abydos, and adjacent regions, marking initial assertions against nominal Memphite or Heracleopolitan overlords. Intef II Wahankh, reigning approximately 2110–2061 BC, intensified expansion with aggressive campaigns, capturing key strongholds like Thinis and clashing directly with Heracleopolitan forces over contested border areas in Middle Egypt.[28] These efforts involved naval and land battles, as evidenced by Theban tomb inscriptions celebrating victories that secured resources and tribute from subjugated nomes.[1] Rivalries with the Heracleopolitan 9th and 10th Dynasties, centered at modern Ihnasya el-Medina, defined Theban ambitions, as the northern kingdom claimed suzerainty over Middle and Lower Egypt while exacting nominal tribute from southern provinces.[4] Conflicts escalated under Intef II, who raided into the Thinite nome and defied Heracleopolitan prohibitions on Theban royal titulary, prompting retaliatory incursions that disrupted trade routes along the Nile.[29] Provincial loyalties shifted dynamically, with nomes like Elephantine and Edfu providing crucial support to Thebes through local elites' initiatives, while Heracleopolis leveraged alliances in the Faiyum and Delta.[1] Intef III, circa 2061–2055 BC, continued these pressures but achieved limited gains, setting the stage for his successor Mentuhotep II's decisive campaigns.[27] The protracted strife highlighted causal factors of resource scarcity and weakened central authority, driving Theban rulers to prioritize military prowess and ideological claims to Horus kingship for legitimacy.[30]Key Regional Figures and Nomarchs

In Upper Egypt, the nomarch Intef, known as "Intef the Elder" or "born of Iku," emerged as a foundational figure in Thebes around 2150 BC, establishing the Eleventh Dynasty through his control of the fourth nome and initiating Theban expansion against northern rivals.[1] His successor, Intef I Sehertawy, proclaimed himself pharaoh and extended Theban influence northward to include Dendera and Koptos, engaging in conflicts with Heracleopolitan forces and local nomarchs to consolidate southern authority.[31] These Theban rulers transitioned from provincial governors to claimants of unified kingship, marking a shift from mere nomarchic autonomy to dynastic ambition. Further south, Ankhtifi, nomarch of the third Upper Egyptian nome centered at Hierakonpolis (Nekhen), wielded exceptional military and administrative power during the late Eighth or early Ninth Dynasty, circa 2100 BC.[32] Loyal to the Heracleopolitan kings, he annexed the neighboring Idfu nome, conducted raids into Theban territory without permanent conquest, and emphasized his role in famine relief and regional stabilization through autobiographical inscriptions in his Moalla tomb, portraying himself as a quasi-pharaonic benefactor who fed the starving across nomes.[32] His actions exemplified the opportunistic expansion by nomarchs amid central weakness, prioritizing local survival over ideological unity. In the north, aligned with Heracleopolis, nomarchs such as those of Siut (Assiut) maintained strategic alliances, with figures like Khety II serving under Tenth Dynasty kings like Merykare, managing provincial defenses and trade routes. These regional leaders, through tomb inscriptions and stelae, documented fortifications against Theban incursions and economic self-sufficiency, underscoring the fragmented power structure where nomarchs negotiated loyalties between rival capitals rather than submitting to a nominal Memphis authority.[33] Such figures' autonomy, evidenced by independent tomb constructions and military campaigns, directly contributed to the prolonged instability until Theban reunification under Mentuhotep II.Path to Reunification

The reunification of Egypt commenced with the expansionist policies of the early Eleventh Dynasty rulers based in Thebes, who challenged the dominance of the Heracleopolitan kingdom controlling Lower and Middle Egypt. Intef I, the founder of the dynasty around 2134 BC, initially consolidated power in Upper Egypt but laid the groundwork for northern incursions.[34] His successors, particularly Intef II (Wahankh, r. c. 2118–2069 BC), initiated direct military confrontations with Herakleopolitan forces, capturing territories as far north as Abydos and possibly engaging in prolonged skirmishes documented in Theban stelae that boast of victories over northern foes.[35] These conflicts, known as the Theban-Herakleopolitan wars, are corroborated by contemporary tomb inscriptions from Asyut in Middle Egypt, which reveal alliances between Herakleopolitan rulers and local nomarchs against Theban aggression, highlighting the protracted nature of the struggle rather than decisive early triumphs.[1] Intef III (Nakhtnebtepnefer, r. c. 2069–2061 BC) further extended Theban influence northward, subduing regions up to the vicinity of Herakleopolis itself, though full control remained elusive amid ongoing resistance from the Ninth and Tenth Dynasty kings. The turning point arrived under Mentuhotep II (Nebhepetre, r. c. 2061–2010 BC), who ascended as a teenager and methodically consolidated power through military campaigns. By his 14th regnal year (c. 2047 BC), Mentuhotep II had overrun key Herakleopolitan strongholds, including the defeat of the last rulers such as Merykare, as proclaimed in his Deir el-Bahri inscriptions that attribute divine favor from Amun for the victories.[36] Archaeological evidence, including reused Herakleopolitan artifacts in Theban contexts and the absence of northern royal monuments post-2055 BC, supports the narrative of Theban hegemony, though Theban royal texts likely amplify successes to legitimize the new order.[37] The final unification, achieved around 2055 BC, marked the transition to the Middle Kingdom, with Mentuhotep II adopting royal titles unifying Upper and Lower Egypt and centralizing administration from Thebes.[34] This process involved not only military conquest but also diplomatic integration of former rivals, as seen in the co-optation of provincial elites and the construction of symbolic monuments like his Deir el-Bahri temple complex, which served to propagate the image of restored cosmic order. While Theban sources dominate the record, potentially biasing portrayals toward inevitability, the cessation of independent northern dynastic claims and renewed Nile Valley trade networks indicate a genuine stabilization of centralized rule.[1]Social and Economic Conditions

Climate Change, Famine, and Demographic Impacts

The onset of the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE) coincided with a prolonged aridification event around 2200 BCE, driven by a weakening of the African monsoon system that reduced summer precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands, the primary source of Nile floodwaters. This led to critically low annual inundations, with paleoclimatic data from sediment cores and speleothems indicating a megadrought spanning over a century across the Mediterranean and Near East, marked by precipitation minima persisting into the early second millennium BCE.[3][8][38] Hydrological records confirm Nile flow failures, including baseflow reductions evidenced by strontium isotopic ratios in ancient sediments, which disrupted the basin irrigation essential to Egyptian agriculture.[39] These climatic shifts precipitated severe famines, as low floods curtailed crop yields for multiple generations, with scholarly reconstructions estimating drought durations exceeding 30–50 years during the late Old Kingdom transition. Archaeological and textual evidence, including reduced grain storage capacities and references to starvation in administrative papyri, underscores widespread food shortages that undermined central authority and fueled provincial autonomy.[7][1] The interplay of environmental stress and inadequate adaptive infrastructure—such as over-reliance on large-scale pyramid projects amid declining productivity—amplified vulnerability, though local nomarchs mitigated some effects through decentralized water management.[40] Demographic consequences included localized population declines from malnutrition and emigration to marginally viable areas, evidenced by sparser settlement densities and fewer elite burials in certain regions compared to the Old Kingdom. However, Egypt's ecological resilience, including fallback to pastoralism and oasis exploitation, limited the scale of loss, with estimates suggesting modest overall impacts rather than catastrophic depopulation; continuity in Lower Egyptian habitation patterns supports this, contrasting with more severe collapses elsewhere.[41][42] Stable isotopic analyses of human remains further indicate nutritional stress without wholesale societal breakdown, aligning with adaptive shifts toward smaller-scale farming communities.[43]Provincial Administration and Power Shifts

The weakening of central authority after the death of Pepi II around 2184 BCE enabled provincial governors, or nomarchs, to assert greater control over local administration, including resource allocation, irrigation management, and militia organization, as the royal court in Memphis lost its ability to enforce oversight.[41] These nomarchs, whose positions had evolved into hereditary roles during the late Sixth Dynasty, increasingly managed nomes as semi-independent entities, prioritizing local survival amid Nile inundation failures that disrupted traditional centralized taxation and labor drafts.[44] In regions like the Dakhla Oasis, local administration demonstrated resilience through reconstruction without defensive fortifications, indicating adaptive provincial governance rather than total anarchy.[44] Power notably shifted to key provincial centers, where nomarchs in Upper Egypt—such as those in Edfu, Hefat, and Thebes—exercised political initiative, erecting tombs and adopting quasi-royal attributes to legitimize their rule. In Middle Egypt, nomarchs of Asyut (the 13th nome) quarried stone at Hatnub and acknowledged the authority of Heracleopolitan kings from the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties, extending their influence to sites like Abydos and Dendera while maintaining local autonomy.[45] Less dominant nomarchs often aligned with either the Heracleopolitan faction in the north, which established a new capital after Memphis, or the Theban rulers in the south, fostering a patchwork of loyalties that fueled regional rivalries and civil conflicts.[44] This decentralization fragmented Egypt into approximately 20 feuding provincial powers under old elites or emerging warlords during the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties, with nomarchs consolidating wealth and military strength that offset the erosion of pharaonic control.[41] Thebes emerged as a pivotal southern power base, challenging Heracleopolitan dominance and controlling much of Upper Egypt, which set the stage for eventual reunification under the Eleventh Dynasty around 2040 BCE.[44] Such shifts preserved core Pharaonic administrative practices at the local level, ensuring cultural continuity despite the absence of unified royal decree.[44]Economic Disruptions and Local Adaptations

The economic foundations of ancient Egypt, reliant on the predictable annual Nile inundations for agriculture and a centralized redistribution system, faced severe disruptions during the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC). Paleoclimatic evidence indicates a prolonged arid phase beginning around 2200 BC, with reduced flood heights leading to crop failures and widespread famine across the Nile Valley.[46][7] This environmental stress exacerbated the political fragmentation, collapsing the Old Kingdom's state-managed granary system that stored surplus grain for redistribution during shortages.[7] Texts like the Admonitions of Ipuwer vividly describe the ensuing chaos, including barren fields, halted trade, and societal starvation where "all is ruin" and "the storehouses are empty."[47] With central authority weakened, long-distance trade networks deteriorated as insecure routes and local conflicts hindered the exchange of goods such as timber, metals, and luxury items from Nubia and the Levant.[48] Agricultural productivity plummeted due to neglected irrigation canals and dikes, previously maintained by royal corvée labor, forcing reliance on inconsistent local flooding.[7] Provincial elites, unburdened by pharaonic oversight, prioritized short-term survival over national economic cohesion, leading to hoarding of resources and irregular taxation that further strained inter-regional flows.[49] In response, nomarchs—governors of Egypt's nomes—adapted by asserting autonomous control over local economies, managing agriculture, and organizing relief distributions to maintain loyalty. Inscriptions from nomarchs in regions like Assiut (ancient Siut) record their provision of grain to famine-stricken populations, portraying themselves as benefactors who fortified granaries and mobilized labor for irrigation repairs.[50][49] These leaders diversified income through intensified local trade in staples like emmer wheat and barley, alongside artisanal production, fostering semi-independent economic hubs resilient to central collapse.[49] Archaeological evidence from settlements such as Abydos reveals expanded community-level crafting and subsistence strategies, including fortified storage and opportunistic herding, which sustained populations amid volatility.[51] This localization, while enabling survival, entrenched economic disparities, with prosperous nomes like the Oryx nome accumulating wealth that funded elite tombs and militias, even as poorer areas endured prolonged hardship.[49] Over time, these adaptations laid groundwork for reunification under stronger regional powers, as nomarchs who effectively stewarded resources gained political leverage.[50]Cultural and Religious Developments

Literature and Prophetic Texts

The literature surviving from or associated with the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE) is sparse, consisting primarily of administrative documents, tomb inscriptions, and biographical texts rather than extended narrative or poetic works. Scholarly consensus holds that no substantial prophetic or literary compositions were produced contemporaneously during this era of political fragmentation; instead, later Middle Kingdom texts (c. 2055–1650 BCE) retrospectively depicted the period's disorders to underscore themes of chaos and restoration. These works, often classified as "pessimistic literature," employ hyperbolic imagery of social upheaval, famine, and moral decay to contrast with the idealized order (ma'at) reestablished under reunified rule.[52] A prominent example is the Prophecy of Neferti, preserved in a Middle Kingdom papyrus copy from the 12th Dynasty (c. 1991–1802 BCE), though set fictitiously in the court of Old Kingdom king Sneferu (c. 2613–2589 BCE). In the narrative, the sage Neferti foretells anarchy mirroring First Intermediate Period conditions—such as nomarchs seizing power, invasions, and societal inversion—before prophesying the advent of a savior king from the south who restores unity, interpreted by scholars as an allusion to Amenemhat I (c. 1985–1956 BCE), founder of the 12th Dynasty. The text's pseudoprophetic structure serves propagandistic purposes, legitimizing Middle Kingdom rule by framing it as divine fulfillment rather than genuine foresight from the period itself.[52][53] Similarly, the Admonitions of Ipuwer, found on a Leiden papyrus dated paleographically to the late Middle Kingdom (c. 19th Dynasty copy, composition likely 12th Dynasty), laments widespread calamity including the Nile turning to blood, collapsed hierarchies, and banditry, evoking First Intermediate Period motifs but lacking direct historical corroboration for the era. Early 20th-century interpretations viewed it as an eyewitness account of the period's collapse, but subsequent linguistic and contextual analysis rejects this, classifying it as didactic wisdom literature composed amid later stability to warn against disorder, with no evidence of First Intermediate Period origin or authenticity as contemporary reportage.[11] The Instructions for Merikare, addressed from a Heracleopolitan king Khety to his son Merikare (nominal 10th Dynasty rulers, c. 2130–2040 BCE), survives in Middle Kingdom manuscripts and offers pragmatic advice on governance, warfare against Theban rivals, and maintaining ma'at amid provincial strife. While referencing First Intermediate Period conflicts, such as campaigns in the south, the text's Middle Egyptian language and polished form indicate composition or redaction in the early 12th Dynasty, possibly as royal instruction (sebayt) drawing on historical memory rather than as an original artifact of the divided era. These texts collectively illustrate how Middle Kingdom authors constructed a literary trope of prophetic lament to rationalize past fragmentation and affirm pharaonic resurgence, rather than documenting lived prophetic traditions from the First Intermediate Period.[54]Religious Practices and Elite Burials

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE), religious practices exhibited continuity with Old Kingdom traditions, such as temple-based worship and the centrality of divine kingship, but decentralization fostered regional variations and innovations. Provincial centers like Edfu and Dendera disseminated religious traditions originally developed in capitals, reflecting the diffusion of cult practices amid political fragmentation. Royal ideology increasingly emphasized divine origins of power, a concept that pharaohs invoked to legitimize authority in contested regions, as seen in inscriptions from nomarchs claiming semi-divine status. Innovations included the widespread use of scarab seals for amuletic protection and the introduction of mummy masks to safeguard the deceased's face, both practices originating in this era and persisting into later dynasties. These artifacts underscore a pragmatic adaptation to resource scarcity, prioritizing portable, symbolic elements over monumental temple endowments. Theban rulers elevated local cults, laying groundwork for the prominence of deities like Montu, evidenced by temple expansions at Armant and Medamud. Elite burials shifted from centralized Memphite pyramids to provincial rock-cut tombs, symbolizing the rise of local power brokers such as nomarchs. In Upper Egypt, Theban kings of the early Eleventh Dynasty pioneered saff tombs at El-Tarif, consisting of a rectangular court with a pillared facade and multiple burial shafts aligned in rows—up to 40 in some cases—designed for royal kin and retainers. These structures marked a departure from Old Kingdom pyramid complexes, emphasizing collective family interment and accessibility amid reduced state resources. Provincial elites, including figures like Ankhtifi in the Hare Nome, constructed mastaba-style or rock-cut tombs at sites such as Deir el-Bersha and Beni Hassan, featuring chapels with reliefs depicting offerings, daily activities, and military exploits to ensure perpetual cult sustenance.[55] Grave goods often included wooden models of boats, granaries, and servants—hundreds in tombs like that of Henu at Deir el-Bersha—serving as substitutes for real labor in the afterlife, a practical response to economic disruptions.[55] Heracleopolitan elites favored decorated tombs in their capital, underscoring rival power centers, though many succumbed to later reuse or erosion due to mudbrick construction. These burials highlight social mobility, with non-royal elites appropriating royal motifs to assert autonomy while nominally deferring to pharaonic authority.[55]Social Stratification and Middle-Class Emergence

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Egypt's social structure retained a hierarchical framework but experienced shifts due to political fragmentation and the rise of provincial autonomy. Nomarchs and local potentates in regions like Asyut, Edfu, and Thebes assumed greater administrative and economic control, amassing wealth through local irrigation projects and resource management, which empowered a stratum of subordinate officials such as stewards and gatekeepers.[1][56] This decentralization facilitated social mobility, as evidenced by the proliferation of private funerary monuments commissioned by non-royal individuals. Artifacts like the limestone statue of Steward Mery from the 11th Dynasty illustrate mid-level administrators achieving prominence through personal service rather than hereditary noble ties.[57] Similarly, stelae such as that of Tjetji highlight officials' autobiographies emphasizing merit and local achievements, diverging from Old Kingdom emphases on royal patronage.[58] Scholars argue this marks the emergence of a middle class—defined as a group between nomarchs and peasants with disposable income for stone stelae and stylized "Second Style" reliefs featuring exaggerated features and familial depictions. Examples include the Stela of Maaty and Dedwi (c. 2170–2008 BC), where a gatekeeper and spouse are portrayed in lively, individualized scenes, reflecting newfound resources amid weakened central authority.[59][60] The thesis posits this class arose from late Old Kingdom disruptions, with nomarchs emulating royal courts and promoting merit-based advancement, leading to a triadic stratification: elites, middling officials/artisans, and laborers.[61] However, the extent of this middle class remains debated, as increased stelae production may reflect regional prosperity rather than broad societal transformation; elite emulation likely drove much of the visible cultural output. Provincial towns like Dendera flourished with disseminated capital traditions, but artistic quality varied, underscoring uneven access to resources.[1] Overall, these developments laid groundwork for Middle Kingdom stability by fostering resilient local hierarchies.[56]Art, Architecture, and Material Culture

Shifts in Artistic Styles

The collapse of centralized authority in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE) prompted a marked departure from the Old Kingdom's canonical artistic conventions, which emphasized strict proportional grids and idealized forms under royal patronage. Provincial workshops proliferated, producing art tailored to local elites and a burgeoning middle class, resulting in diverse regional styles that prioritized functionality and accessibility over monumental precision.[1][34] Reliefs and stelae from Upper Egyptian sites, such as Abydos and Thebes, deviated from Memphite norms with narrower shoulders, rounded limbs, and elevated waistlines, often executed in high raised or deeply sunk techniques to accommodate less skilled local carvers. These works incorporated novel motifs, including military scenes of nomarchs as archers or victors, reflecting the era's power struggles and social mobility rather than pharaonic ideology. Examples include the stela of Iku and Mer-imat, which exemplifies provincial naturalism and familial groupings atypical of Old Kingdom formality.[56][62][63] Statuary during this period extended the late Old Kingdom "Second Style," characterized by more expressive facial features, dynamic postures, and subtle modeling that presaged Middle Kingdom developments, though quality varied due to decentralized production. Innovations like scarab seals and early mummy masks emerged alongside these shifts, signaling adaptations in funerary art driven by broader societal participation.[61][64][1]Tomb Construction and Monumentality

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE), tomb construction shifted dramatically from the centralized, massive pyramid complexes of the Old Kingdom to smaller, regionally focused structures, reflecting the era's political fragmentation and diminished capacity for large-scale labor mobilization. Provincial nomarchs and elites, operating with greater autonomy amid weakened royal authority, prioritized rock-cut tombs excavated into cliffs near their power bases, such as at Asyut, Qau, and Mo'alla, rather than stone-faced superstructures requiring extensive state resources. These tombs typically featured multi-chambered layouts with pillared halls for offerings and biographical inscriptions, but lacked the engineering precision and scale of earlier Memphite pyramids, underscoring a broader decline in monumentality tied to economic decentralization and resource scarcity.[65][66] At Asyut, tombs of the 9th and 10th Dynasty nomarchs, including those of Ityfy I and Khety, exemplify this trend with expansive rock-cut complexes boasting large halls supported by four pillars (originally, contrary to earlier reconstructions showing two) and detailed reliefs depicting daily life, hunts, and conquests to legitimize local rule. The tomb of Ankhtifi, a powerful nomarch from the 9th Dynasty at Mo'alla, innovated by selecting a standalone, pyramid-shaped hill for its symbolic evocation of the benben mound and eternal stability, integrating landscape features into funerary design in ways absent from Old Kingdom standardization. Such adaptations prioritized symbolic and propagandistic elements over sheer size, with coarser carving techniques and irregular hieroglyphs indicating reliance on local artisans rather than centralized guilds.[66][67] Mudbrick mastabas persisted in some areas, particularly for non-elite burials, but their vulnerability to erosion—unlike durable stone—highlights the period's logistical constraints and focus on functionality over permanence. Monumental output waned as no single authority could command the Nile Valley-wide corvée labor or quarrying operations that defined Old Kingdom pharaonic tombs, leading to an emphasis on decorated interiors and stelae for afterlife provisioning rather than exterior grandeur. This provincial proliferation, with thousands of tombs documented at sites like Qau-Matmar, signals increased social stratification and middle-class participation in funerary practices, yet overall scale remained modest, foreshadowing the modest royal saff-tombs emerging at Thebes by the late period.[56][68][61]Crafts and Everyday Artifacts

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE), crafts and everyday artifacts exhibited marked regional variations, stemming from the era's political decentralization, which disrupted centralized workshops of the Old Kingdom and fostered local production centers in Upper and Lower Egypt. Pottery, a staple of daily life for storage, cooking, and transport, showed distinct stylistic divergences; in Upper Egypt, traditional ovoid forms gave way to baggy, less symmetrical shapes, interpreted by some scholars as adaptations to provincial kilns and clays rather than a uniform decline in quality.[69] These vessels were typically unglazed earthenware, fired in simple updraft kilns, with surfaces smoothed by hand or early wheel techniques, and occasional incised or painted decorations limited to geometric patterns due to resource constraints.[34] Faience production, involving quartz paste glazed with copper compounds, persisted for small-scale items like beads and amulets, often shaped as scarab seals—a FIP innovation that combined practical use as stamps with symbolic protective functions, influencing later dynasties.[1] Amulets depicting body parts, such as eyes or limbs, appeared in burials, suggesting continuity in apotropaic crafts using mold-casting for mass production among non-elites.[70] Tools for everyday tasks, including copper adzes, chisels, and sickles, maintained Old Kingdom forms with straight-edged blades hafted to wooden handles, as evidenced by tomb deposits, indicating no major technological rupture despite economic disruptions.[71] Household artifacts like basketry and linen weaving tools—spindle whorls of baked clay and bone needles—reflected practical continuity, with flax processing for textiles supporting local economies in the absence of grand state projects. Regional workshops in nomarch territories, such as at Herakleopolis, yielded stratified pottery assemblages showing gradual evolution from late Old Kingdom marl clays to coarser Nile silts, underscoring adaptive craftsmanship amid famine and trade interruptions.[72] Overall, these artifacts highlight resilience in vernacular production, prioritizing utility over the monumental aesthetics of prior eras.Historiographical Perspectives

Evidence from Inscriptions and Texts

![Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati][float-right] The primary textual evidence for the First Intermediate Period derives from provincial inscriptions, particularly tomb autobiographies of nomarchs, which highlight decentralized authority and local initiatives amid weakened central control.[1] These texts, often carved in Upper Egyptian necropoleis like Moalla and Abydos, emphasize personal achievements in warfare, famine relief, and resource distribution, with minimal references to pharaonic oversight.[73] For instance, the inscriptions of Ankhtifi, nomarch of the Edfu and Hierakonpolis regions circa 2100 BCE, detail his military campaigns against neighboring nomes, claiming to have "pacified the two nomes" without apparent royal mandate and organized grain shipments to famine-stricken areas, underscoring regional autonomy.[74] Royal texts from the Heracleopolitan dynasty (Dynasties 9–10, circa 2160–2025 BCE) provide insight into northern governance and inter-regional conflict. The Instructions of Merikare, preserved in later New Kingdom copies but attributed to a father-son exchange between Khety III and Merikare, advises on maintaining order through justice, military preparedness against Theban rivals, and pragmatic alliances, reflecting efforts to legitimize rule amid fragmentation.[45] Similarly, Theban inscriptions from Dynasty 11 rulers, such as Intef I and Intef II, assert kingship titles and conquests over southern nomes, as seen in stelae and tomb reliefs claiming expansion from Elephantine to Abydos.[65] Funerary stelae and minor administrative texts further illustrate social continuity and emerging local elites. The Stela of Maati, a gatekeeper from the period, records offerings and familial ties, evidencing persistent bureaucratic roles despite political instability. Nomarchs like Iti-Ibi of Assiut inscribed claims of royal education and loyalty to Heracleopolis, yet their accumulation of titles—such as "overseer of priests" and "great chief"—signals devolved power structures.[1] The scarcity of datable royal annals or temple dedications contrasts with Old Kingdom abundance, suggesting disrupted scribal traditions under Memphis's nominal successors in Dynasties 7–8.[2] Debates persist regarding the interpretive bias in these self-aggrandizing inscriptions, which may exaggerate chaos to glorify local heroes, as later Middle Kingdom narratives retroactively framed the era as disorderly to exalt reunification under Mentuhotep II.[45] Nonetheless, the corpus consistently portrays adaptive governance by provincial leaders, with evidence of sustained literacy and ideological continuity in ma'at-centered rhetoric.[1]Debate on Chaos versus Continuity

The historiographical debate on the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE) centers on whether it represented a profound societal collapse marked by anarchy, famine, and civil strife, or a phase of decentralized continuity with regional adaptations preserving core administrative and cultural structures. Traditional interpretations, drawing from Middle Kingdom-era texts such as the Admonitions of Ipuwer and Instructions of Merikare, depict the era as one of existential disorder, with descriptions of inverted social hierarchies, temple desecrations, and widespread violence used retrospectively to legitimize the Theban reunification under Mentuhotep II.[1] These literary sources, however, reflect propagandistic biases favoring pharaonic centralization, potentially exaggerating instability to contrast with the purported order of the Middle Kingdom.[75] Archaeological evidence challenges the chaos narrative, revealing sustained local governance and economic activity under nomarchs (provincial rulers) who maintained Old Kingdom-style titles, bureaucracies, and irrigation systems without evidence of total breakdown. Inscriptions from figures like Ankhtifi of Hierakonpolis detail organized military expeditions and resource distribution, indicating functional hierarchies rather than anarchy, while provincial tombs—such as those at Beni Hasan and Asyut—continued to feature elaborate constructions and elite burials, suggesting prosperity in regions detached from Memphis's weakening control.[1] Utilitarian ceramics and settlement data from sites like Elephantine further demonstrate continuity in production techniques and trade networks, with minimal disruptions in everyday material culture.[76] Scholars like Stephen Seidlmayer argue that the period's "crisis" was more a redistribution of power to nomarchs amid climatic stresses like Nile floods' variability, rather than wholesale societal failure, as evidenced by the absence of widespread destruction layers in excavations.[77] This view posits adaptive resilience, with Heracleopolitan and Theban dynasties (9th–11th) exercising nominal oversight over nomes, fostering a "middle class" emergence through broader access to stelae and titles previously reserved for elites.[75] Critics of the continuity model, however, point to the scarcity of datable royal monuments and textual laments' consistency as indicators of genuine fragmentation, though these are increasingly seen as selective rather than comprehensive records.[78] The debate underscores tensions between literary historiography, prone to ideological distortion, and empirical archaeology, which prioritizes verifiable continuity in provincial spheres over centralized decline. Recent reassessments emphasize that while central authority eroded—likely due to overextension and environmental factors—the period enabled innovations in literature and administration that facilitated Middle Kingdom revival, framing it less as "dark age" than transitional decentralization.[79][1]Implications for Understanding State Resilience

The First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE) exposed vulnerabilities in the Egyptian state's centralized structure, particularly its dependence on reliable Nile inundations for agricultural surplus that sustained pharaonic bureaucracy and monumental projects. Prolonged droughts and low floods, linked to broader aridification around 2200 BCE, triggered famine and economic contraction, eroding central fiscal control as provincial nomarchs retained local revenues rather than remitting them to Memphis.[41] [7] This fragmentation highlighted how over-centralization without robust local redundancies amplifies risks from environmental shocks, as the pharaoh's ideological role as guarantor of ma'at (cosmic order) failed to mitigate material crises, leading to rival power centers in Heracleopolis and Thebes.[1] Despite this, the period underscores state resilience through decentralized adaptation and cultural continuity. Nomarchs, while autonomous, preserved Old Kingdom administrative practices, legal norms, and scribal traditions at the local level, enabling provinces to weather scarcity without total societal breakdown—evident in sustained provincial tomb constructions and textual records of resource management.[77] The pharaonic system's ideological durability allowed Theban rulers like Intef II and Mentuhotep II to legitimize conquests by invoking unified kingship rhetoric, culminating in reunification by c. 2055 BCE without wholesale reinvention of governance.[80] This recovery path illustrates how shared religious and symbolic frameworks can serve as "soft infrastructure" for state reformation, contrasting with polities lacking such cohesion that succumb permanently to division. For broader understanding of ancient state durability, the era reveals that resilience hinges less on peak institutional strength than on adaptive flexibility: rigid hierarchies falter under exogenous stressors, but embedded cultural norms and semi-autonomous subunits foster rebound. Egypt's repeated cycles of unity and fragmentation—unique in its persistence over millennia—demonstrate that political collapse need not equate to civilizational end, provided latent ideological claims enable elite realignment, a dynamic less evident in contemporaneous Near Eastern states facing similar climatic pressures.[81] [82] Scholarly reassessments emphasize continuity over "chaos" narratives derived from later propagandistic texts, attributing durability to endogenous factors like elite networks rather than exogenous invasions, though debates persist on the extent of Heracleopolitan versus Theban agency in stabilization.[83]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Limestone_Statue_of_the_Steward_Mery.jpg