Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Loperamide

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /loʊˈpɛrəmaɪd/ |

| Trade names | Imodium, others[1] |

| Other names | R-18553, Loperamide hydrochloride (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682280 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 0.3% |

| Protein binding | 97% |

| Metabolism | Liver (extensive) |

| Elimination half-life | 9–14 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Feces (30–40%), urine (1%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.053.088 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

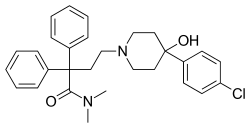

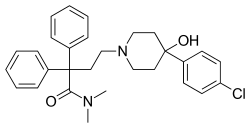

| Formula | C29H33ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 477.05 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Loperamide, sold under the brand name Imodium, among others,[1] is a medication of the opioid receptor agonist class used to decrease the frequency of diarrhea.[6][5] It is often used for this purpose in irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, short bowel syndrome,[5] Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis.[6] Loperamide is taken by mouth.[5]

Common side effects include abdominal pain, constipation, sleepiness, vomiting, and dry mouth.[5] It may increase the risk of toxic megacolon.[5] Loperamide's safety in pregnancy is unclear, but no evidence of harm has been found.[7] It appears to be safe in breastfeeding.[8] It is an opioid with no significant absorption from the gut and does not cross the blood–brain barrier when used at normal doses.[9] It works by slowing the contractions of the intestines.[5]

Loperamide was first made in 1969 and used medically in 1976.[10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11] Loperamide is available as a generic medication.[5][12] In 2023, it was the 276th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 800,000 prescriptions.[13][14]

Medical uses

[edit]Loperamide is effective for the treatment of a number of types of diarrhea.[15]

Loperamide is often compared to diphenoxylate. Studies suggest that loperamide is more effective and has lower neural side effects.[16][17][18]

Side effects

[edit]Adverse drug reactions most commonly associated with loperamide are constipation (which occurs in 1.7–5.3% of users), dizziness (up to 1.4%), nausea (0.7–3.2%), and abdominal cramps (0.5–3.0%).[3] Rare, but more serious, side effects include toxic megacolon, paralytic ileus, angioedema, anaphylaxis/allergic reactions, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, urinary retention, and heat stroke.[19] The most frequent symptoms of loperamide overdose are drowsiness, vomiting, and abdominal pain, or burning.[20] High doses may result in heart problems such as abnormal heart rhythms.[21]

Contraindications

[edit]Treatment should be avoided in the presence of high fever or if the stool is bloody. Treatment is not recommended for people who could have negative effects from rebound constipation. If suspicion exists of diarrhea associated with organisms that can penetrate the intestinal walls, such as E. coli O157:H7 or Salmonella, loperamide is contraindicated as a primary treatment.[3] Loperamide treatment is not used in symptomatic C. difficile infections, as it increases the risk of toxin retention and precipitation of toxic megacolon.

Loperamide should be administered with caution to people with liver failure due to reduced first-pass metabolism.[22] Additionally, caution should be used when treating people with advanced HIV/AIDS, as cases of both viral and bacterial toxic megacolon have been reported. If abdominal distension is noted, therapy with loperamide should be discontinued.[23]

Children

[edit]A review of loperamide in children under twelve years of age found that serious adverse events occurred only in children under three years of age.[24] The study reported that the use of loperamide should be contraindicated in children who are under three years of age, systemically ill, malnourished, moderately dehydrated, or have bloody diarrhea.[24]

In 1990, all formulations of loperamide for children were banned in Pakistan.[25]

Formulations for children aged less than twelve years of age are only available via prescription in the UK.[26]

Pregnancy and breast feeding

[edit]Loperamide is not recommended in the United Kingdom for use during pregnancy or by nursing mothers.[27] Studies in rat models have shown no teratogenicity, but sufficient studies in humans have not been conducted.[28] One controlled, prospective study of 89 women exposed to loperamide during their first trimester of pregnancy showed no increased risk of malformations. This, however, was only one study with a small sample size.[29] Loperamide can be present in breast milk and is not recommended for breastfeeding mothers.[23]

Drug interactions

[edit]Loperamide is a substrate of P-glycoprotein; therefore, the concentration of loperamide increases when given with a P-glycoprotein inhibitor.[3] Common P-glycoprotein inhibitors include quinidine, ritonavir, and ketoconazole.[30] Loperamide can decrease the absorption of some other drugs. As an example, saquinavir concentrations can decrease by half when given with loperamide.[3]

Loperamide is an antidiarrheal agent, which decreases intestinal movement. As such, when combined with other antimotility drugs, the risk of constipation is increased. These drugs include other opioids, antihistamines, antipsychotics, and anticholinergics.[31]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

Loperamide is an opioid-receptor agonist and acts on the μ-opioid receptors in the myenteric plexus of the large intestine. It works like morphine, decreasing the activity of the myenteric plexus, which decreases the tone of the longitudinal and circular smooth muscles of the intestinal wall.[32][33] This increases the time material stays in the intestine, allowing more water to be absorbed from the fecal matter. It also decreases colonic mass movements and suppresses the gastrocolic reflex.[34]

Loperamide's circulation in the bloodstream is limited in two ways. Efflux by P-glycoprotein in the intestinal wall reduces the passage of loperamide, and the fraction of drug crossing is then further reduced through first-pass metabolism by the liver.[35][36] Loperamide metabolizes into an MPTP-like compound, but is unlikely to exert neurotoxicity.[37]

Blood–brain barrier

[edit]Efflux by P-glycoprotein also prevents circulating loperamide from effectively crossing the blood-brain barrier,[38] so it can generally only agonize mu-opioid receptors in the peripheral nervous system, and currently has a score of one on the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale.[39] Concurrent administration of P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as quinidine potentially allows loperamide to cross the blood-brain barrier and produce central morphine-like effects. At high doses (>70mg), loperamide can saturate P-glycoprotein (thus overcoming the efflux) and produce euphoric effects.[40] Loperamide taken with quinidine was found to produce respiratory depression, indicative of central opioid action.[41]

High doses of loperamide have been shown to cause a mild physical dependence during preclinical studies, specifically in mice, rats, and rhesus monkeys. Symptoms of mild opiate withdrawal were observed following abrupt discontinuation of long-term treatment of animals with loperamide.[42][43]

Chemistry

[edit]Synthesis

[edit]Loperamide is synthesized starting from the lactone 3,3-diphenyldihydrofuran-2(3H)-one and ethyl 4-oxopiperidine-1-carboxylate, on a lab scale.[44] On a large scale a similar synthesis is followed, except that the lactone and piperidinone are produced from cheaper materials rather than purchased.[45][46]

Physical properties

[edit]Loperamide is typically manufactured as the hydrochloride salt. Its main polymorph has a melting point of 224 °C and a second polymorph exists with a melting point of 218 °C. A tetrahydrate form has been identified which melts at 190 °C.[47]

History

[edit]Loperamide hydrochloride was first synthesized in 1969[10] by Paul Janssen from Janssen Pharmaceuticals in Beerse, Belgium, following previous discoveries of diphenoxylate hydrochloride (1956) and fentanyl citrate (1960).[48]

The first clinical reports on loperamide were published in 1973[44] with the inventor being one of the authors. The trial name for it was "R-18553".[49] Loperamide oxide has a different research code: R-58425.[50]

The trial against placebo was conducted from December 1972 to February 1974, its results being published in 1977.[51]

In 1973, Janssen started to promote loperamide under the brand name Imodium. In December 1976, Imodium got US FDA approval.[52]

During the 1980s, Imodium became the best-selling prescription antidiarrheal in the United States.[53]

In March 1988, McNeil Pharmaceutical began selling loperamide as an over-the-counter drug under the brand name Imodium A-D.[54]

In the 1980s, loperamide also existed in the form of drops (Imodium Drops) and syrup. Initially, it was intended for children's usage, but Johnson & Johnson voluntarily withdrew it from the market in 1990 after 18 cases of paralytic ileus (resulting in six deaths) were registered in Pakistan and reported by the World Health Organization (WHO).[55] In the following years (1990-1991), products containing loperamide have been restricted for children's use in several countries (ranging from two to five years of age).[56]

In the 1980s, before the US patent expired on 30 January 1990,[53] McNeil started to develop Imodium Advanced containing loperamide and simethicone for treating both diarrhea and gas. In March 1997, the company patented this combination.[57] The drug was approved in June 1997, by the FDA as Imodium Multi-Symptom Relief in the form of a chewable tablet.[58] A caplet formulation was approved in November 2000.[59]

In November 1993, loperamide was launched as an orally disintegrating tablet based on Zydis technology.[60][61]

In 2013, loperamide was added to the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines.[11][62]

Society and culture

[edit]Legal status

[edit]United States

[edit]Loperamide was formerly a controlled substance in the United States. First, it was a Schedule II controlled substance. However, this was lowered to Schedule V. Loperamide was finally removed from control by the Drug Enforcement Administration in 1982, courtesy of then-Administrator Francis M. Mullen Jr.[63]

UK

[edit]Loperamide can be sold freely to the public by chemists (pharmacies) as the treatment of diarrhea and acute diarrhea associated with medically diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome to adults aged 18 years of age and older.[64]

Economics

[edit]Loperamide is available as a generic medication.[5][12] In 2016, Imodium was one of the biggest-selling branded over-the-counter medications sold in Great Britain, with sales of £32.7 million.[65]

Brand names

[edit]Loperamide was originally sold as Imodium, and many generic brands are sold.[1]

Off-label/unapproved use

[edit]Loperamide has typically been deemed to have a relatively low risk of misuse.[66] In 2012, no reports of loperamide abuse were made.[67] In 2015, however, case reports of extremely high-dose loperamide use were published.[68][69] The primary intent of users has been to manage symptoms of opioid withdrawal such as diarrhea, although a small portion derive psychoactive effects at these higher doses.[70] At these higher doses central nervous system penetration occurs and long-term use may lead to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal on abrupt cessation.[70] Dubbing it "the poor man's methadone", clinicians warned that increased restrictions on the availability of prescription opioids enacted in response to the opioid epidemic were prompting recreational users to turn to loperamide as an over-the-counter treatment for withdrawal symptoms.[71] The FDA responded to these warnings by calling on drug manufacturers to voluntarily limit the package size of loperamide for public-safety reasons.[72][73] However, there is no quantity restriction on number of packages that can be purchased, and most pharmacies do not feel capable of restricting its sale, so it is unclear that this intervention will have any impact without further regulation to place loperamide behind the counter.[74] Since 2015, several reports of sometimes-fatal cardiotoxicity due to high-dose loperamide abuse have been published.[75][76]

Research

[edit]In 2020, some research found that loperamide is effective at killing glioblastoma cells.[77]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Loperamide (International database)". Drugs.com. 5 October 2025. Retrieved 11 October 2025.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Imodium A-D- loperamide hydrochloride solution". DailyMed. 23 September 2025. Retrieved 11 October 2025.

- ^ "Loperamide Hydrochloride capsule". DailyMed. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Loperamide Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ a b "About loperamide". nhs.uk. 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Loperamide use while Breastfeeding". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "loperamide hydrochloride". NCI Drug Dictionary. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b Patrick GL (2013). An introduction to medicinal chemistry (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 644. ISBN 978-0-19-969739-7. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2025). The selection and use of essential medicines, 2025: WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, 24th list. Geneva: World Health Organization. doi:10.2471/B09474. hdl:10665/382243. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b Hamilton RJ (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia (14 ed.). [Sudbury, Mass.]: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-4496-7361-1. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2023". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 17 August 2025. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Loperamide Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2014 - 2023". ClinCalc. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Hanauer SB (Winter 2008). "The role of loperamide in gastrointestinal disorders". Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders. 8 (1): 15–20. PMID 18477966.

- ^ Miftahof R (2009). Mathematical Modeling and Simulation in Enteric Neurobiology. World Scientific. p. 18. ISBN 978-981-283-481-2. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- ^ Benson A, Chakravarthy A, Hamilton SR, Elin S, eds. (2013). Cancers of the Colon and Rectum: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-936287-58-1. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Zuckerman JN (2012). Principles and Practice of Travel Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-118-39208-9. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "loperamide adverse reactions". Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Litovitz T, Clancy C, Korberly B, Temple AR, Mann KV (1997). "Surveillance of loperamide ingestions: an analysis of 216 poison center reports". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 35 (1): 11–9. doi:10.3109/15563659709001159. PMID 9022646.

- ^ "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Loperamide (Imodium): Drug Safety Communication - Serious Heart Problems With High Doses From Abuse and Misuse". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "rxlist.com". 2005. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ a b Li ST, Grossman DC, Cummings P (2007). "Loperamide therapy for acute diarrhea in children: systematic and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 4 (3) e98. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040098. PMC 1831735. PMID 17388664.

- ^ "E-DRUG: Chlormezanone". Essentialdrugs.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- ^ "Who can and cannot take loperamide". NHS England. 20 May 2024. Retrieved 11 October 2025.

- ^ "Medicines information links - NHS Choices". Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Einarson A, Mastroiacovo P, Arnon J, Ornoy A, Addis A, Malm H, et al. (March 2000). "Prospective, controlled, multicentre study of loperamide in pregnancy". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (3): 185–7. doi:10.1155/2000/957649. PMID 10758415.

- ^ "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Loperamide Drug Interactions - Epocrates Online". online.epocrates.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ "DrugBank: Loperamide". Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Loperamide Hydrochloride Drug Information, Professional". Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Katzung BG (2004). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (9th ed.). Lange Medical Books/McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-141092-2.[page needed]

- ^ Lemke TL, Williams DA (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 675. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Dufek MB, Knight BM, Bridges AS, Thakker DR (March 2013). "P-glycoprotein increases portal bioavailability of loperamide in mouse by reducing first-pass intestinal metabolism". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 41 (3): 642–50. doi:10.1124/dmd.112.049965. PMID 23288866. S2CID 11014783.

- ^ Kalgutkar AS, Nguyen HT (September 2004). "Identification of an N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-like metabolite of the antidiarrheal agent loperamide in human liver microsomes: underlying reason(s) for the lack of neurotoxicity despite the bioactivation event". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 32 (9): 943–52. doi:10.1016/S0090-9556(24)02977-5. PMID 15319335. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Upton RN (August 2007). "Cerebral uptake of drugs in humans". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 34 (8): 695–701. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04649.x. PMID 17600543. S2CID 41591261.

- ^ "Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Antoniou T, Juurlink DN (June 2017). "Loperamide abuse". CMAJ. 189 (23): E803. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161421. PMC 5468105. PMID 28606977.

- ^ Sadeque AJ, Wandel C, He H, Shah S, Wood AJ (September 2000). "Increased drug delivery to the brain by P-glycoprotein inhibition". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 68 (3): 231–7. doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.109156. PMID 11014404. S2CID 38467170.

- ^ Yanagita T, Miyasato K, Sato J (1979). "Dependence potential of loperamide studied in rhesus monkeys". NIDA Research Monograph. 27: 106–13. PMID 121326.

- ^ Nakamura H, Ishii K, Yokoyama Y, Motoyoshi S, Suzuki K, Sekine Y, et al. (November 1982). "[Physical dependence on loperamide hydrochloride in mice and rats]". Yakugaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 102 (11): 1074–85. doi:10.1248/yakushi1947.102.11_1074. PMID 6892112.

- ^ a b Stokbroekx RA, Vandenberk J, Van Heertum AH, Van Laar GM, Van der Aa MJ, Van Bever WF, et al. (July 1973). "Synthetic antidiarrheal agents. 2,2-Diphenyl-4-(4'-aryl-4'-hydroxypiperidino)butyramides". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (7): 782–786. doi:10.1021/jm00265a009. PMID 4725924.

- ^ US 3714159, Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, issued 1973

- ^ US 3884916, Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, issued 1975

- ^ Van Rompay J, Carter JE (January 1990). Florey K (ed.). "Loperamide hydrochloride". Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances. 19. Academic Press: 341–365. doi:10.1016/s0099-5428(08)60372-x. ISBN 978-0-12-260819-3.

- ^ Florey K (1991). Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology, Volume 19. Academic Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-08-086114-2. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Schuermans V, Van Lommel R, Dom J, Brugmans J (1974). "Loperamide (R 18 553), a novel type of antidiarrheal agent. Part 6: Clinical pharmacology. Placebo-controlled comparison of the constipating activity and safety of loperamide, diphenoxylate and codeine in normal volunteers". Arzneimittelforschung. 24 (10): 1653–7. PMID 4611432.

- ^ "Compound Report Card". Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Mainguet P, Fiasse R (July 1977). "Double-blind placebo-controlled study of loperamide (Imodium) in chronic diarrhoea caused by ileocolic disease or resection". Gut. 18 (7): 575–9. doi:10.1136/gut.18.7.575. PMC 1411573. PMID 326642.

- ^ "IMODIUM FDA Application No.(NDA) 017694". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1976. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ a b McNeil-PPC, Inc., Plaintiff, v. L. Perrigo Company, and Perrigo Company, Defendants, 207 F. Supp. 2d 356 (E.D. Pa. 25 June 2002).

- ^ "IMODIUM A-D FDA Application No.(NDA) 019487". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1988. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ "Loperamide: voluntary withdrawal of infant fomulations" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 4 (2): 73–74. 1990. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

The leading international supplier of this preparation, Johnson and Johnson, has since informed WHO that having regard to the dangers inherent in improper use and overdosing, this formulation (Imodium Drops), was voluntarily withdrawn from Pakistan in March 1990. The company has since decided not only to withdraw this preparation worldwide but also to remove all syrup formulations from countries where WHO has a programme for the control of diarrhoeal diseases.

- ^ Consolidated List of Products Whose Consumption And/or Sale Have Been Banned, Withdrawn, Severely Restricted Or Not Approved by Governments, 8th Issue. United Nations. 2003. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-92-1-130230-1. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ US patent 5612054, Jeffrey L. Garwin, "Pharmaceutical compositions for treating gastrointestinal distress", issued 18 March 1997, assigned to McNeil-PPC, Inc.

- ^ "IMODIUM MULTI-SYMPTOM RELIEF FDA Application No.(NDA) 020606". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1997. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Imodium Advanced (Loperamide HCI and Simethicone NDA #21-140". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Scherer announces launch of another product utilizing its Zydis technology". PR Newswire Association LLC. 9 November 1993. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ Rathbone MJ, Hadgraft J, Roberts MS (2002). "The Zydis Oral Fast-Dissolving Dosage Form". Modified-Release Drug Delivery Technology. CRC Press. pp. 200. ISBN 978-0-8247-0869-6. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ World Health Organization (2014). The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2013 (including the 18th WHO model list of essential medicines and the 4th WHO model list of essential medicines for children). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/112729. ISBN 978-92-4-120985-4. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series;985.

- ^ Mullen F (3 November 1982). "FR Doc. 82-30264" (PDF). Federal Register. DEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "BNF is only available in the UK".

- ^ Connelly D (April 2017). "A breakdown of the over-the-counter medicines market in Britain in 2016". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 298 (7900). Royal Pharmaceutical Society. doi:10.1211/pj.2017.20202662. ISSN 2053-6186.

- ^ Baker DE (2007). "Loperamide: a pharmacological review". Reviews in Gastroenterological Disorders. 7 (Suppl 3): S11-8. PMID 18192961.

- ^ Mediators and Drugs in Gastrointestinal Motility II: Endogenous and Exogenous Agents. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-3-642-68474-6. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ MacDonald R, Heiner J, Villarreal J, Strote J (May 2015). "Loperamide dependence and abuse". BMJ Case Reports. 2015: bcr2015209705. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-209705. PMC 4434293. PMID 25935922.

- ^ Dierksen J, Gonsoulin M, Walterscheid JP (December 2015). "Poor Man's Methadone: A Case Report of Loperamide Toxicity". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 36 (4): 268–70. doi:10.1097/PAF.0000000000000201. PMID 26355852. S2CID 19635919.

- ^ a b Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA (2017). "Loperamide, the "Poor Man's Methadone": Brief Review". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 49 (1): 18–21. doi:10.1080/02791072.2016.1260188. PMID 27918873. S2CID 31713818.

- ^ Guarino B (4 May 2016). "Abuse of diarrhea medicine you know well is alarming physicians". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ McGinley L (30 January 2018). "FDA wants to curb abuse of Imodium, 'the poor man's methadone'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Office of the Commissioner. "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Imodium (loperamide) for Over-the-Counter Use: Drug Safety Communication - FDA Limits Packaging To Encourage Safe Use". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Feldman R, Everton E (November 2020). "National assessment of pharmacist awareness of loperamide abuse and ability to restrict sale if abuse is suspected". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 60 (6): 868–873. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.05.021. PMID 32641253. S2CID 220436708.

- ^ Eggleston W, Clark KH, Marraffa JM (January 2017). "Loperamide Abuse Associated With Cardiac Dysrhythmia and Death". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 69 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.03.047. PMID 27140747.

- ^ Mukarram O, Hindi Y, Catalasan G, Ward J (2016). "Loperamide Induced Torsades de Pointes: A Case Report and Review of the Literature". Case Reports in Medicine. 2016 4061980. doi:10.1155/2016/4061980. PMC 4775784. PMID 26989420.

- ^ "Anti-diarrhoea drug drives cancer cells to cell death". Aktuelles aus der Goethe-Universität Frankfurt. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020.

Loperamide

View on GrokipediaLoperamide is a synthetic phenylpiperidine derivative that functions as a mu-opioid receptor agonist, primarily employed as an antidiarrheal medication to reduce gastrointestinal motility and secretion in the treatment of acute nonspecific diarrhea and chronic diarrhea associated with inflammatory bowel disease.[1][2] By binding to opioid receptors in the intestinal myenteric plexus, it inhibits peristalsis, prolongs gut transit time, and enhances absorption of water and electrolytes, thereby decreasing stool frequency and volume.[1][2] First synthesized in 1969 by researchers at Janssen Pharmaceutica and approved for medical use in 1976, loperamide is marketed under the brand name Imodium and available over-the-counter in many countries for self-treatment of diarrhea, reflecting its established efficacy and favorable safety profile at recommended doses of up to 16 mg per day for adults.[3][2] Its peripheral action stems from poor penetration of the blood-brain barrier under therapeutic conditions, minimizing central opioid effects while targeting gut-specific receptors.[1][2] However, supratherapeutic doses, often exceeding 100 mg daily, have been increasingly abused since the 2010s as a surrogate for opioids to achieve euphoria or mitigate withdrawal symptoms, circumventing its central exclusion via P-glycoprotein inhibition or massive intake.[4][5] This misuse has precipitated severe cardiotoxicity, including QT interval prolongation, ventricular dysrhythmias such as torsades de pointes, and fatal cardiac arrest, prompting FDA warnings in 2016 about the risks of high-dose ingestion and subsequent regulatory efforts to limit package sizes.[4][6][5] Empirical data from case reports and surveillance indicate that such toxicity arises from loperamide's blockade of cardiac ion channels, including hERG potassium and sodium channels, at elevated plasma concentrations.[2][5]

Clinical Applications

Approved Indications

Loperamide is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the symptomatic relief of acute nonspecific diarrhea in adults and children aged 2 years and older, where it reduces stool frequency and consistency without addressing underlying causes. For diarrhea from food poisoning, which often involves bacterial pathogens, loperamide can provide symptomatic relief in select cases lacking signs of invasive infection (such as bloody stools or fever), but is not always recommended as slowing intestinal motility may prolong toxin exposure and potentially worsen the illness; hydration with oral rehydration solutions should be prioritized, as dehydration represents the primary risk.[7][8] Clinical guidelines recommend an initial oral dose of 4 mg, followed by 2 mg after each unformed stool, not exceeding 16 mg per day in adults or 3 mg per day in children aged 6-8 years (with weight-based adjustments for younger children), and discontinuation if no improvement occurs within 48 hours.[9][10] This indication extends to traveler's diarrhea, with evidence from controlled trials showing efficacy in shortening episode duration when used adjunctively with rehydration.[2][1] For chronic diarrhea linked to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, loperamide is indicated for ongoing symptom control at maintenance doses of 4-8 mg daily, up to a maximum of 16 mg per day under physician oversight to avoid complications like toxic megacolon during acute flares.[2][11] Studies in IBD patients demonstrate sustained reduction in stool frequency, with one trial reporting effective relief in 21 of 27 participants, dropping average daily stools from eight to fewer than three.[12] Loperamide is also approved to decrease ileostomy output volume, mitigating risks of dehydration and electrolyte disturbances in patients with high-output stomas.[13] Randomized controlled trials confirm a median output reduction of 16.5% (range -5% to 46%) with standard dosing, alongside slowed intestinal transit, improving patient hydration status and quality of life without altering stool sodium concentration significantly.[14][15] Dosing for this use typically starts at 2-4 mg daily, titrated based on response and monitored for tolerability.[16]Off-Label Uses

Loperamide is employed off-label for managing chemotherapy-induced diarrhea, particularly associated with agents like irinotecan, where aggressive dosing—such as 2 mg every 2 hours—has reduced severe episode incidence to approximately 9% in clinical studies. Initial administration typically involves 4 mg followed by 2 mg after each loose stool, with daily limits up to 16 mg in specialized protocols, though persistence beyond 48 hours necessitates switching to alternatives like octreotide to mitigate risks of ileus or incomplete resolution. While effective as first-line symptomatic relief in many cases, evidence from guidelines underscores the need for close monitoring due to variable efficacy across chemotherapy regimens and potential for high-dose cardiac complications.[2][17][18] Higher-than-standard doses of loperamide are used off-label to control output in high-output stoma or short bowel syndrome, aiming to reduce fluid losses through enhanced gut motility inhibition; dosing may escalate to 4-16 mg daily or more under specialist supervision, with monitoring for dehydration and electrolyte imbalances essential given the paucity of large randomized trials. Similarly, in chronic diarrheas linked to inflammatory bowel disease beyond routine indications, small studies report marked symptom improvement in 68% of cases involving ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease, though long-term data remain limited and benefits must be balanced against risks of dependency or toxic megacolon in active inflammation. Loperamide is also utilized off-label for symptomatic relief of diarrhea in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D), with as-needed dosing typically ranging from 2-16 mg daily in divided doses under medical guidance. However, it is not suitable for continuous daily long-term administration, particularly in mixed IBS (IBS-M), due to the risk of exacerbating constipation during non-diarrheal phases; guidelines recommend episodic use to manage acute symptoms while minimizing adverse effects.[19][20][21][22] As an adjunct for mild opioid withdrawal symptoms, loperamide is sometimes self-administered due to its peripheral mu-opioid agonism alleviating cramps and diarrhea, but clinical endorsement is absent owing to sparse controlled evidence, high abuse potential, and documented cardiotoxicity at supratherapeutic doses exceeding 70 mg daily. Case series indicate misuse prevalence aligns with opioid epidemic trends, yet prospective studies highlight inefficacy for central symptoms like anxiety and elevated risks of QT prolongation, rendering it unsuitable as formal therapy. Rare palliative use in secretory diarrheas from neuroendocrine tumors, such as carcinoid syndrome, provides transient relief but lacks disease-modifying effects and is overshadowed by somatostatin analogs like octreotide, with primary literature emphasizing evidence gaps over routine application.[2][23][24]Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

Loperamide functions as a selective agonist at mu-opioid receptors located in the myenteric plexus of the intestinal wall, where it inhibits the release of acetylcholine and other excitatory neurotransmitters from enteric neurons, thereby suppressing peristaltic contractions and reducing propulsive motility in the gut.[25] This action prolongs intestinal transit time, allowing greater reabsorption of water and electrolytes from luminal contents, which empirically decreases stool volume and frequency in diarrheal states.[1] Manometry studies in humans and animal models confirm this by demonstrating dose-dependent prolongation of small bowel and colonic transit without significant impact on gastric emptying or proximal motility.[26] Additionally, loperamide enhances internal anal sphincter tone through similar mu-opioid mediated inhibition of inhibitory neural pathways, contributing to fecal continence by resisting premature evacuation.[27] Beyond motility effects, loperamide exerts antisecretory actions by modulating ion transport in intestinal enterocytes, particularly inhibiting cyclic AMP- and calcium-dependent chloride secretion across the mucosal epithelium, which reduces fluid accumulation in the gut lumen.[28] This has been observed in vitro using Ussing chambers with rabbit ileal mucosa and rat colonic preparations, where loperamide attenuated chloride efflux stimulated by secretagogues like prostaglandin E2 or enterotoxins, and corroborated in human biopsy studies showing decreased fecal water loss independent of motility changes.[29][30] At therapeutic doses (typically 2-16 mg daily), loperamide exhibits minimal systemic opioid activity, lacking analgesia or euphoria, due to its recognition as a substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an efflux transporter abundantly expressed in the intestinal epithelium and blood-brain barrier that actively pumps the drug out of enterocytes and back into the gut lumen or excludes it from central nervous system entry.[31] This peripheral restriction ensures actions remain localized to the gastrointestinal tract, as evidenced by undetectable or low plasma levels post-oral administration and absence of central pupillary effects in pharmacodynamic assessments.[2]Pharmacokinetics

Loperamide demonstrates poor oral bioavailability of approximately 0.3%, primarily attributable to extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver following absorption from the gastrointestinal tract.[1] Peak plasma concentrations occur 4 to 5 hours post-administration, with levels remaining low even at therapeutic doses; for instance, after a single 2 mg dose, unchanged drug concentrations do not exceed 2 ng/mL.[32] [2] This limited systemic exposure confines its primary effects to peripheral mu-opioid receptors in the gut, as evidenced by plasma assays in clinical pharmacokinetic studies.[33] The drug is highly bound to plasma proteins (97%), which further restricts free fractions available for distribution beyond the gastrointestinal tract.[1] Metabolism occurs predominantly in the liver via oxidative N-demethylation, mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C8, yielding the active metabolite N-desmethyl loperamide.[2] [1] Elimination follows an apparent half-life of 9.1 to 14.4 hours, with the majority (>90%) excreted unchanged in feces via biliary secretion and minimal renal clearance (<1% as parent compound).[2] [32] In chronic therapeutic use, steady-state plasma concentrations remain sub-therapeutic for central nervous system effects, typically ranging from 0.2 to 1.2 ng/mL, as confirmed by assays in dosing trials adhering to recommended limits (up to 16 mg daily).[34] Phase I studies indicate that food intake may delay time-to-peak absorption without significantly altering overall bioavailability.[35]Blood-Brain Barrier Dynamics

Loperamide, a substrate for the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp, encoded by ABCB1/MDR1), exhibits restricted penetration across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) due to active extrusion from the central nervous system (CNS).[36] At therapeutic doses, typically up to 16 mg per day for adults, P-gp maintains negligible brain concentrations, as evidenced by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with radiolabeled ¹¹C-loperamide or its N-desmethyl metabolite, which shows low and stable uptake (standardized uptake value ~15%) in human and wild-type rodent brains.[37] In P-gp-deficient mouse models, brain uptake increases dramatically (up to 16-fold), confirming the transporter's causal role in limiting CNS exposure under normal conditions.[38] Supraphysiologic doses, often exceeding 50–100 mg in misuse scenarios, can overwhelm P-gp transport capacity, enabling dose-dependent accumulation in the brain and manifestation of opioid-like central effects such as euphoria or respiratory depression.[39] This saturation mechanism is supported by pharmacokinetic principles and case observations where high plasma levels correlate with CNS penetration, distinct from therapeutic pharmacokinetics where barrier integrity remains intact.[31] Inhibition of P-gp pharmacologically further elevates brain loperamide levels, inducing opioid agonist activity, underscoring the transporter's saturability rather than an absolute barrier.[40] Genetic variants in MDR1, such as the C3435T polymorphism, have been investigated for potential influence on loperamide disposition, but clinical studies in humans demonstrate no significant association with altered plasma concentrations or CNS effects.[41] Population-level data thus indicate limited vulnerability from common polymorphisms at standard doses, reinforcing that BBB dynamics pose no inherent risk in approved use while highlighting dose escalation as the primary disruptor.[42] This distinction counters unsubstantiated concerns of routine CNS liability, grounded instead in transporter kinetics.Adverse Effects and Safety Profile

Effects at Therapeutic Doses

At therapeutic doses, loperamide primarily causes mild gastrointestinal and central nervous system effects, with constipation reported in 1.7% to 5.3% of patients across clinical trials for acute and chronic diarrhea, alongside abdominal cramps (1.4%), nausea (1.8%), dizziness (1.4%), dry mouth, flatulence, and drowsiness.[43][2] These effects are typically self-limiting and resolve upon dose reduction or discontinuation, contributing to the drug's established safety profile for short-term antidiarrheal use in adults.[43] Rare serious adverse events at recommended doses include toxic megacolon, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or conditions impairing intestinal motility, such as ulcerative colitis; loperamide is contraindicated in acute dysentery, pseudomembranous colitis, bacterial enterocolitis caused by invasive organisms, or abdominal pain without diarrhea due to risks of worsening these states by inhibiting peristalsis.[43][2] In pediatric patients, loperamide is contraindicated for those under 2 years of age owing to the potential for central nervous system depression and serious cardiac events, with cautious use recommended in children aged 2 to 12 years at the lowest effective dose to minimize dehydration risks or variability in response.[43][2] For breastfeeding, loperamide is excreted into human milk, though at low concentrations; use requires weighing benefits against possible infant effects like constipation or diarrhea, with monitoring advised.[43][2] Loperamide carries a pregnancy category C designation, with animal reproduction studies showing no evidence of teratogenicity or fetal harm, but limited controlled data in humans; administration is advised only when potential benefits justify possible risks, particularly avoiding unnecessary use in the first trimester.[43][2] Overall, post-marketing surveillance and controlled trial data affirm a low incidence of severe adverse events at therapeutic doses (typically 4-16 mg/day for adults), supporting its risk-benefit favorability for indicated antidiarrheal therapy.[43]Overdose and Toxicity Risks

Overdoses of loperamide, typically involving ingestion of 40 to 100 times the recommended therapeutic dose (exceeding 160 mg daily), can precipitate severe gastrointestinal stasis, manifesting as paralytic ileus, megacolon, or toxic megacolon due to exaggerated mu-opioid receptor agonism in the enteric nervous system.[44] [2] Central nervous system effects, including sedation, miosis, and respiratory depression, occur infrequently in isolated loperamide overdose because of poor blood-brain barrier penetration under normal conditions, but may emerge with cofactors such as P-glycoprotein inhibitors (e.g., quinidine) or CYP3A4 inhibitors that elevate plasma concentrations and enable central opioid activity.[45] Cardiac toxicity predominates in severe cases, with doses exceeding 200 mg linked to dose-dependent blockade of the hERG potassium channel, resulting in QT interval prolongation, torsades de pointes, ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and sudden death; the FDA's Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) has documented multiple fatalities in this context, often involving intentional high-dose abuse.[46] [47] [48] Management centers on gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal if ingestion occurred within 1 to 4 hours, alongside supportive measures such as fluid resuscitation, electrolyte correction, and continuous ECG monitoring; for arrhythmias, intravenous magnesium sulfate is indicated to stabilize cardiac membranes, while no specific antidote exists, and naloxone proves ineffective against predominantly peripheral opioid effects.[49] [50] Population-level toxicity risk remains low, with U.S. poison center reports of loperamide-related exposures numbering in the low hundreds annually (e.g., 41 abuse/misuse calls in 2014, rising modestly thereafter) against billions of over-the-counter doses sold yearly, indicating that adverse outcomes stem primarily from deliberate supratherapeutic dosing rather than routine use or inherent pharmacological peril.[51] [52]Drug Interactions

Pharmacodynamic Interactions

Loperamide, acting as a mu-opioid receptor agonist primarily in the gastrointestinal tract, can interact pharmacodynamically with other agents that modulate intestinal motility. Concomitant use with additional opioid agonists, such as codeine or diphenoxylate, leads to additive suppression of peristalsis and prolongation of gut transit time, elevating the risk of severe constipation, paralytic ileus, or toxic megacolon.[53][54] This potentiation arises from shared agonism at enteric mu-opioid receptors, which inhibit acetylcholine release and reduce propulsive activity. Additive effects also occur with anticholinergic medications, including antispasmodics like dicyclomine or hyoscyamine, due to combined inhibition of muscarinic receptors in the gut smooth muscle. Loperamide possesses weak intrinsic antimuscarinic activity, and coadministration exacerbates hypomotility, further increasing susceptibility to constipation and ileus.[53][55] In terms of cardiac pharmacodynamics, loperamide at supratherapeutic concentrations inhibits hERG potassium channels and sodium channels, potentially prolonging the QT interval. Concurrent use with other QT-prolonging drugs, such as fluoroquinolone antibiotics (e.g., moxifloxacin) or macrolides (e.g., erythromycin), may synergistically heighten the risk of QTc prolongation and torsades de pointes via compounded ion channel blockade, even if loperamide remains at therapeutic levels.[56][57] Caution is warranted, as case reports document amplified arrhythmogenic potential in such combinations.[4] Prokinetic agents like metoclopramide, which promote gastrointestinal motility through dopamine D2 antagonism and enhanced acetylcholine release, can antagonize loperamide's antimotility effects, potentially diminishing its antidiarrheal efficacy. This opposition, while not always resulting in clinically documented interactions, stems from mechanistic counteraction on enteric neural pathways.[58][59]Pharmacokinetic Interactions

Loperamide undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism primarily via oxidative N-demethylation by CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 enzymes in the liver, with limited oral bioavailability of approximately 0.3% due to this process and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux in the gut.[1] [2] Concomitant administration of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as ketoconazole or ritonavir, significantly elevates loperamide plasma concentrations by inhibiting its metabolism; for instance, coadministration with ketoconazole increased area under the curve (AUC) by approximately 5-fold and maximum concentration (C_max) by 3- to 4-fold in pharmacokinetic studies.[60] [43] Similarly, CYP2C8 inhibitors like gemfibrozil can raise plasma levels up to 4-fold, amplifying risks of toxicity including QT prolongation at supratherapeutic exposures.[34] [43] P-gp inhibitors, such as quinidine, primarily enhance central nervous system penetration of loperamide rather than substantially altering systemic plasma levels, as demonstrated in studies where quinidine coadministration increased brain uptake without proportional changes in peripheral concentrations, leading to opioid-like effects including miosis and respiratory depression.[61] [31] This interaction exploits loperamide's substrate affinity for P-gp at the blood-brain barrier, potentially enabling euphoria or abuse when combined, though plasma elevations remain modest (2- to 3-fold at most).[60] [62] CYP3A4 inducers like rifampin decrease loperamide exposure by accelerating its metabolism, potentially reducing antidiarrheal efficacy in patients on chronic polypharmacy; while direct interaction studies are limited, general pharmacokinetic principles for CYP3A4 substrates predict substantial reductions in AUC (up to 90% in analogous cases), necessitating dose adjustments or monitoring of therapeutic response.[63] [1] These pharmacokinetic alterations underscore the need for caution in polypharmacy, particularly with antiretrovirals or antifungals that overlap inhibitory effects.[64]Abuse, Misuse, and Controversies

Motivations for Abuse

Loperamide misuse primarily stems from its exploitation as an inexpensive opioid surrogate to produce euphoria or mitigate withdrawal symptoms amid tightened restrictions on prescription opioids and heroin. Case series and user reports document abusers consuming 50–300 mg daily—exceeding therapeutic limits by over tenfold—to bypass P-glycoprotein efflux and achieve central opioid agonism.[65][66] This pattern emerged as individuals with opioid use disorder sought unregulated alternatives during the post-2010 escalation of regulatory crackdowns on controlled analgesics.[67] Over-the-counter status, exemplified by formulations like Imodium A-D, lowers barriers to procurement for self-treatment, enabling rapid escalation in dependent users facing scarcity. Yet, abuse remains rare, with U.S. poison center data logging fewer than 200 intentional misuse exposures annually through 2016 despite millions of opioid-dependent individuals, equating to under 1% involvement per national surveys of substance users.[68][66] Such sparsity highlights misuse as driven by individual volition rather than inherent product flaws or broad accessibility failures.[69] Poison control trends reveal a 91% surge in loperamide exposures from 2010 to 2015, temporally aligned with opioid prescription curbs, but without substantiation for a gateway role in broader escalation—therapeutic consumers overwhelmingly adhere to labeled dosing without progression.[67] Empirical tracking via the National Poison Data System underscores that reported incidents, while rising modestly, constitute a marginal fraction of overall opioid-related calls, affirming limited propagation beyond self-selected cohorts.[70]Physiological Effects of High-Dose Use

At sufficiently high doses, typically exceeding 70 mg daily, loperamide saturates P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pumps at the blood-brain barrier, enabling significant central nervous system penetration and mu-opioid receptor agonism.[1] [71] This results in opioid-mimetic effects including sedation, euphoria, analgesia, and respiratory depression, akin to low-potency mu-agonists such as codeine, though with delayed onset due to loperamide's pharmacokinetics.[34] [62] Receptor saturation models, supported by pharmacokinetic studies, predict these outcomes as plasma concentrations rise to levels where P-gp transport capacity is overwhelmed, allowing cerebrospinal fluid accumulation and direct brainstem mu-receptor activation.[71] Autopsy data from overdose cases corroborate central opioid effects, with histopathological evidence of hypoxic neuronal injury consistent with respiratory depression, though often confounded by concurrent cardiotoxicity.[49] Chronic high-dose administration induces tolerance to central mu-agonism, necessitating dose escalation—often to hundreds of milligrams daily—to sustain effects, mirroring classical opioid pharmacodynamics where receptor downregulation and desensitization occur.[5] Withdrawal upon cessation manifests as standard opioid abstinence syndrome, featuring anxiety, myalgias, piloerection, and dysphoria, but uniquely complicated by gastrointestinal dysmotility; abrupt discontinuation exacerbates intestinal hypermotility and secretory diarrhea due to unopposed rebound from loperamide's peripheral antisecretory actions.[72] [45] These symptoms can be mitigated by mu-agonists like buprenorphine, underscoring shared mechanistic pathways with other opioids.[72] Therapeutic doses (≤16 mg/day) exhibit negligible addictive liability, as P-gp restriction precludes meaningful CNS exposure and reward signaling.[1] High-dose dependency remains uncommon outside contexts of pre-existing substance use disorders, where individuals exploit loperamide's availability to self-medicate opioid withdrawal, rather than initiating de novo abuse.[62] [39] This pattern aligns with loperamide's low intrinsic reward potency compared to centrally acting opioids, limited by its partial agonism profile and pharmacokinetic barriers at non-excessive exposures.[45]Cardiovascular Complications

High doses of loperamide potently inhibit the human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel, delaying cardiac repolarization and prolonging the QTc interval on electrocardiograms, with values exceeding 500 ms documented in clinical cases of abuse.[73][47] This mechanism underlies ventricular arrhythmias, including torsades de pointes, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and sudden cardiac arrest, as evidenced by case series linking supratherapeutic ingestion (typically 50–300 mg daily) to these outcomes.[5][74] Empirical ECG data from affected patients confirm causality through reversal of abnormalities following drug cessation and supportive care, though persistent QTc prolongation has been observed for weeks post-exposure in chronic abusers.[75] Surveillance reports highlight these risks in misuse contexts, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documenting cardiac dysrhythmias and four deaths among 195 U.S. poison center cases involving loperamide abuse from January to June 2016 alone.[65] Medical examiner reviews of fatalities frequently identify loperamide as contributory or primary, often alongside polydrug use (e.g., opioids or sedatives), which amplifies exposure via pharmacokinetic interactions like CYP3A4 or P-glycoprotein inhibition.[76][77] In one analysis of 21 North Carolina deaths, the drug was deemed additive or causal in 19 instances, underscoring the role of elevated serum levels in arrhythmogenesis.[76] At recommended therapeutic doses (≤16 mg/day), cardiovascular events remain rare, with randomized trials showing no QTc prolongation of clinical concern even at single supratherapeutic doses up to 48 mg.[78] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's 2016 warning emphasized high-dose risks based on post-marketing reports of QT prolongation and arrhythmias, but these were exceptional relative to widespread safe use.[4]Public Health and Regulatory Responses

In response to reports of loperamide abuse leading to cardiac toxicity, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety communication on June 7, 2016, warning of serious heart rhythm problems, including QT prolongation and torsades de pointes, associated with doses exceeding recommended therapeutic levels of up to 16 mg per day.[4] On January 30, 2018, the FDA announced voluntary packaging limits for over-the-counter loperamide products, capping cartons at 48 mg total (equivalent to a three-day supply at maximum approved doses) and requiring unit-dose blister packaging to deter bulk ingestion for non-medical purposes; these measures were approved for implementation by September 2019.[79] [80] Data from the National Poison Data System indicate these interventions correlated with a decline in loperamide-related exposures involving abuse or intentional misuse, which peaked at a rate of 0.02 per 1,000 total exposures in 2015 before decreasing to 0.01 by 2022, reflecting roughly a 50% reduction in abuse-associated cases post-restrictions, though overall exposures remained stable.[70] This outcome suggests efficacy in curbing reported overdoses through reduced accessibility of large quantities, as poison center calls for serious outcomes (e.g., cardiac events) also trended downward after 2016.[70] However, critics argue such limits may inadvertently elevate black-market sourcing or substitution with more hazardous alternatives, potentially offsetting public health gains without comprehensive evidence of net harm reduction.[2] Internationally, loperamide remains available over-the-counter without U.S.-style quantity caps in numerous countries, including much of Europe and Canada, where abuse incidence appears lower relative to opioid epidemic contexts, prompting questions about the necessity of stringent U.S. measures amid varying baseline risks.[2] Regulatory divergences highlight potential over-reliance on paternalistic restrictions in the U.S., which may impede legitimate access for scenarios like extended travel or acute diarrhea outbreaks, where self-limiting therapeutic use predominates and severe self-harm remains rare outside vulnerable subpopulations.[68] Emphasis on education regarding dose limits and cardiac risks, rather than packaging constraints, could better promote personal responsibility while preserving utility for the majority of users. Market data from 2023 onward show steady global loperamide sales growth, projected to rise from approximately USD 3.5 billion in 2025 to USD 5.2 billion by 2032 at a compound annual growth rate of around 5-6%, indicating no disruption to therapeutic demand or emergence of an abuse-driven epidemic despite warnings.[81] This stability underscores that regulatory responses have mitigated acute misuse signals without broader supply chain impacts, though ongoing surveillance is warranted to assess unintended access barriers.Chemistry

Chemical Structure and Properties

Loperamide hydrochloride is the hydrochloride salt form of 4-[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxypiperidin-1-yl]-N,N-dimethyl-2,2-diphenylbutanamide, with the molecular formula C29H34Cl2N2O2 and a molecular weight of 513.5 g/mol.[82] The compound is achiral, possessing no stereocenters, which eliminates the need for stereochemical control in synthesis or formulation to ensure therapeutic consistency.[83] Loperamide exhibits high lipophilicity, characterized by an octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) of 5.13, contributing to its limited aqueous solubility of approximately 0.14 g/100 mL at pH 1.7 and slight solubility in neutral water.[3][84] The hydrochloride salt form enhances solubility in dilute acids compared to the free base, facilitating dissolution in gastrointestinal conditions.[85] Freely soluble in organic solvents such as methanol and chloroform, it supports various extraction and analytical procedures.[3] The melting point of loperamide hydrochloride is 223–225 °C, indicating thermal stability suitable for solid oral dosage forms like capsules, tablets, and liquids.[84] It remains stable under physiological pH conditions (approximately 1.2–7.4 in the gastrointestinal tract), with a pKa of 8.66 ensuring protonation and cationic form predominance at these pH values, which minimizes degradation and supports consistent bioavailability in formulations.[84][3]| Property | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 513.5 g/mol | PubChem |

| logP | 5.13 | PubChem |

| Melting Point | 223–225 °C | ChemicalBook |

| Water Solubility (pH 1.7) | 0.14 g/100 mL | ScienceDirect |