Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

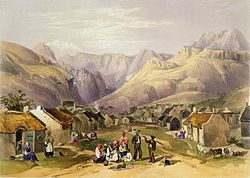

Genadendal

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Genadendal [χəˈnɑːdəndal] is a town in the Western Cape province of South Africa, built on the site of the oldest mission station in the country. It was originally known as Baviaanskloof, but was renamed Genadendal in 1806.[2][3] Genadendal was the place of the first Teachers' Training College in South Africa, founded in 1838.[4][5]

Location

[edit]Genadendal (Valley of Grace) is approximately 90 minutes drive east of Cape Town in the Riviersonderend Mountains, in the Overberg region.[6]

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Genadendal has a rich spiritual history and was the first mission station in southern Africa. It was founded by George Schmidt, a German missionary of the Moravian Church, who settled on 23 April 1738 in Baviaanskloof (Ravine of the Baboons) in the Riviersonderend Valley and began to evangelise among the Khoi people.[7][8] The Moravian Church (originated in 1457 in Moravia, today part of the Czech Republic) had a particular zeal for mission work.[9] Many thought that mission work among the Khoisan was attempting the impossible, but in spite of this Schmidt prevailed. He became acquainted with an impoverished and dispersed Khoi people who were practically on the threshold of complete extinction. Apart from the few Kraals, which still remained, there were already thirteen farms in the vicinity of Baviaanskloof. Within a short while Schmidt formed a small Christian congregation. He taught the Khoi to read and write, but when he began to baptise his converts there was great dissatisfaction among the Cape Dutch Reformed Church clergy. According to them, Schmidt was not an ordained minister and as such, was not permitted to administer the sacraments. Consequently, he had to abandon his work, and in 1744, after seven years at Baviaanskloof, he left the country.[10]

Schmidt's first converts (1742)

[edit]A letter from Count Nicolaus Zinzendorf (who was a Moravian bishop) had arrived giving him permission to baptise his followers.[11] The first to be baptised were: Africo who was baptised as Christian, Wilhelm baptised as Josua, Vehettge baptised as Magdalena (Lena), Kyboddo baptised as Jonas and Christina, who was the sister of Moses.[12]

Rekindling of the Mission (1792)

[edit]On Christmas Eve in 1792, Christian Kühnel, Daniel Schwinn and Henrik Marsveld, three Moravian missionaries, arrived at Baviaanskloof and were shown the ruins of Schmidt's house and the hamlet in which no one lived anymore.[13] The missionaries found Mother/Moeder (Magda) Lena, one of Schmidt's first converts on a farm near Sergeants River. She played a role in keeping the faith alive by reading from the New Testament Bible that had been given to her by Schmidt. These meetings would take place under the pear tree that Schmidt had planted in Baviaanskloof.[14] After finding Lena at Sergeants River, the missionaries held their first service under the same tree. The three missionaries quickly settled in and built a house that would adequately suit their needs.[15] Some of the materials being taken from Schmidt's house.[16] Thus, Baviaanskloof as a settlement had begun again.[17]

Importantly though, they were not able to put up a church as they did not have the required permit from the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and it did not seem that they would be granted one anytime soon.[18] During the first British occupation at the Cape (1795-1803) the missionaries were permitted to build more buildings.[19] The first building to be built was a place to worship, and the chapel was consecrated in 1796, but it soon became apparent that the chapel was too small for the congregation. According to Krüger (p. 77): “The foundation was made of stone, the walls of clay, the roof of straw, the floor was smeared with cow-dung.” In March 1797 they built a forge, and soon one of the missionaries, Kühnel, who was a knife maker (cutler), began using the forge to make Hernnhut knives. These knives put Baviaanskloof on the map as a source of quality knives within the colony.[20]

The hamlet that once was had begun to flourish again. Between 1796 and 1797 the Moravian community had built a chapel, a forge, and their mill – the mill being crucial because it meant that they no longer had to go to surrounding farms to use a mill.[21] There were many similarities between the new settlement and the settlement of Schmidt’s time. In those years, gardens were keenly tended and used to provide food. There were many homes built of clay, Krüger (p. 80) writes: “Every inhabitant had a vegetable garden adjoining his dwelling. The houses in the village were built of clay, some still in the shape of a bee-hive (matjieshuis) with an opening on the top for smoke, while others were square with a thatched roof. The interior was mostly unfurnished, with a kettle on the fire and hides for the night.” Lena had died only five days before the new church had been consecrated. This signalled the passing of the last known connection with the original settlement that Schmidt alongside her and others had started. And in 1806 in the midst of the second British occupation becoming permanent, Baviaanskloof was renamed Genadendal (Valley of Grace) by the missionaries.[22]

Genadendal's Library (1823)

[edit]In 1823, Genadendal had its own library where the villagers could borrow books or sit and read in the reading room.[23] There were books available in English, Dutch and German. The library became known for its bustling activity, as books were circulating so fast that demand was more than supply.[23] The increased interaction with literature also helped politicise some villagers, aiding them in the raising of their political consciousness.[23]

Archaeology at Genadendal

[edit]Archaeological excavations at Genadendal focused on different locations. Excavations were carried out at three shelters and at the mission station.[24] The shelters revealed Middle Stone Age flakes, pieces of indigenous pottery, stone tools but also contemporary glass, likely from windows and bottles.[24] The area in the village where the excavation took place was roughly the area where Schmidt's house was said to have been, along with two other sites: Kühnel house and a cottage.[24] Interestingly, there was not a lot of evidence of activity on the surface level, despite the centuries of human habitation.[24] In the missionaries diaries, they mentioned that they took materials from Schmidt’s structure and incorporated it into their own house that they built.[24][16]

It was discovered that most of the ceramics found were made in the mid to late 19th century, with no real trace (except for the physical buildings) of the 18th century mission station.[24] There were some traces of 18th century ceramics.[24] Clift (p. 82) explains that this could be the sparse nature of goods in an 18th century mission in the frontier.[24] With regards to Schmidt’s house, there was no evidence to show the exact location of where it was, from where the excavation took place.[24]

Genadendal Archaeology Project (1999)

[edit]The Genadendal Archaeology Project was an educational project in which the University of Cape Town's archaeological department's education outreach, known as the Research Unit for the Archaeology of Cape Town (RESUNACT) worked together with the Genadendal Mission Museum, Emil Weder High School and Swartberg Secondary School.[24] Emil Weder High School is in Genadendal and Swartberg Secondary School is in Caledon. The aim of the project was to bring to the students resources that will help them not only understand the history of Genadendal but also to equip them with tools to research historical topics.[24] An additional aim was also to provide educational material for the teachers and the Genadendal Mission Museum. The project was able to introduce teachers and students to the tools and techniques of archaeology, and provide a foundation, alongside support material, for students interested in exploring the history of Genadendal and surrounding areas.[24]

The students did excavations at Kühnel house, learnt to survey one of the old cottages on Berg Street and explored the Khoi history and origins of the region.[24] Their work culminated in an exhibition, where they could display the knowledge they had gained, and introduce others to what the project was about.[24]

Genadendal Residence

[edit]Genadendal Residence, the official Cape Town residence of the President of South Africa, is named after the town.[25]

Books about Genadendal

[edit]- Bernhard Krüger (1966), "The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869."

- Isaac Balie (1988), "Die Geskiedenis van Genadendal,1738-1988."

- Isaac Balie (1987), "Genadendal Historical Outline."

- Isaac Balie (1992), "Genadendal: Its Golden Age, 1806-1870."

- Georg Schmidt et al (1981), "Das Tagebuch und die Briefe von Georg Schmidt, dem ersten Misionar in Südafrika (1737-1744)."

- Val Nowlan (2015), "Valley of Grace."

- Hendrik Marsveld et al (1999), "The Genadendal Diaries: Diaries of the Herrnhut Missionaries, H.Marsveld, D.Schwinn, and J.C.Kühnel."

- J. de Boer & E.M. Temmers (1987),"Unitas Fratrum: Two Hundred Years of Missionary and Pastoral Service in Southern Africa (Western Region)."

- Russel Viljoen (1992), "Moravian Missionaries, Khoikhoi labour and the Overberg Colonists at the end of the VOC era, 1792-1796."

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Main Place Genadendal". Census 2011.

- ^ "Dictionary of Southern African Place Names (Public Domain)". Human Science Research Council. p. 71.

- ^ Balie, Isaac (1988). Die Geskiedenis van Genadendal, 1738-1988. Kaapstad: Perskor.

- ^ Balie, Isaac (1988). Die Geskiedenis van Genadendal, 1738-1988. Kaapstad: Perskor.

- ^ de Waal, Jan (1995). Emil Weder High School in Genadendal: A Case Study in the Concept of Effective Schooling (Thesis). University of Cape Town.

- ^ "Genadendal". Theewaterskloof Municipality. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Bredekamp, H.C.J (1997). "Construction and Collapse of a Herrnhut Mission Community at the Cape, 1737-1743". Kronos (24): 46–61.

- ^ Christensen, Carsten Sander (2017). "The History of the Moravian Church Rooting in Unitas Fratrum or the Unity of the Brethren (1457-2017) Based on the Description of the Two Settlements of Christiansfeld and Sarepta". Studia Humanitatis. 3. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Balie, Isaac (1988). Die Geskiedenis van Genadendal, 1738-1988. Kaapstad: Perskor.

- ^ a b Marsveld, Hendrik; Schwinn, Daniel; Kühnel, Johan Christian; Bredekamp, H.C.; Plüddeman, H.E.F. (1992). The Genadendal Diaries: Diaries of Herrnhut Missionaries, H.Marsveld, D.Schwinn and J.C. Kühnel. Bellville: University of Western Cape, Institute for Historical Research.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Balie, Isaac (1988). Die Geskiedenis van Genadendal, 1738-1988. Kaapstad: Perskor.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Balie, Isaac (1988). Die Geskiedenis van Genadendal, 1738-1988. Kaapstad: Perskor.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ Krüger, Bernhard (1966). The Pear Tree Blossoms: The History of the Moravian Church in South Africa 1737-1869. Genadendal: The Moravian Book Depot.

- ^ a b c Dick, Archie (2013). The Hidden History of South Africa's Book and Reading Cultures. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Clift, Harriet (2001). A Sortie into the Archaeology of a Moravian Mission Station, Genadendal (Thesis). University of Cape Town.

- ^ Weber, Rebecca (11 December 2013). "Revisiting Nelson Mandela's Genadendal". USA Today. Retrieved 6 December 2015.