Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

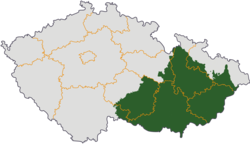

Moravia

View on Wikipedia

Moravia[a][9] is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

Key Information

The medieval and early modern Margraviate of Moravia was a crown land of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown from 1348 to 1918, an imperial state of the Holy Roman Empire from 1004 to 1806, a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867, and a part of Austria-Hungary from 1867 to 1918. Moravia was one of the five lands of Czechoslovakia founded in 1918. In 1928 it was merged with Czech Silesia, and then dissolved in 1948 during the abolition of the land system following the communist coup d'état.

Its area of 22,623.41 km2[b] is home to about 3.0 million of the Czech Republic's 10.9 million inhabitants.[5] The people are historically named Moravians, a subgroup of Czechs, the other group being called Bohemians.[12][13] The land takes its name from the Morava river, which runs from its north to south, being its principal watercourse. Moravia's largest city and historical capital is Brno. Before being sacked by the Swedish army during the Thirty Years' War, Olomouc served as the Moravian capital, and it is still the seat of the Archdiocese of Olomouc.[4] Until the expulsions after 1945, significant parts of Moravia were German speaking.

Toponymy

[edit]The region and former margraviate of Moravia, Morava, in Czech, is named after its principal river Morava.

The German name for Moravia is Mähren, from the river's German name March. This could have a different etymology, as march is a term used in the medieval times for an outlying territory, a border or a frontier (cf. English march). In Latin, the name Moravia was used.

Geography

[edit]Moravia occupies most of the eastern part of the Czech Republic. Moravian territory is naturally strongly determined, in fact, as the Morava river basin, with strong effect of mountains in the west (de facto main European continental divide) and partly in the east, where all the rivers rise.

Moravia occupies an exceptional position in Central Europe. All the highlands in the west and east of this part of Europe run west–east, and therefore form a kind of filter, making north–south or south–north movement more difficult. Only Moravia with the depression of the westernmost Outer Subcarpathia, 14–40 kilometers (9–25 mi) wide, between the Bohemian Massif and the Outer Western Carpathians (gripping the meridian at a constant angle of 30°)[clarification needed], provides a comfortable connection between the Danubian and Polish regions, and this area is thus of great importance in terms of the possible migration routes of large mammals[14] – both as regards periodically recurring seasonal migrations triggered by climatic oscillations in the prehistory, when permanent settlement started.

Moravia borders Bohemia in the west, Lower Austria in the southwest, Slovakia in the southeast, Poland for a short distance in the north, and Czech Silesia in the northeast. Its natural boundary is formed by the Sudetes mountains in the north, the Carpathians in the east and the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands in the west (the border runs from Králický Sněžník in the north, over Suchý vrch, across the Upper Svratka Highlands and Javořice Highlands to a tripoint near Slavonice in the south). The Thaya river meanders along the border with Austria, and the tripoint of Moravia, Austria and Slovakia is at the confluence of the Thaya and Morava rivers. The northeast border with Silesia runs partly along the Moravice, Oder and Ostravice rivers. Between 1782 and 1850, Moravia (also thus known as Moravia-Silesia) also included a small portion of the former province of Silesia – the Austrian Silesia. (When Frederick the Great annexed most of ancient Silesia (the land of upper and middle Oder river) to Prussia, Silesia's southernmost part remained with the Habsburgs.)

Today Moravia includes the South Moravian and Zlín regions, the vast majority of the Olomouc Region, the southeastern half of the Vysočina Region and parts of the Moravian-Silesian, Pardubice and South Bohemian regions.

Geologically, Moravia covers an area between the Bohemian Massif and the Carpathians (from northwest to southeast), and between the Danube basin and the North European Plain (from south to northeast). Its core geomorphological features are three wide valleys, namely the Dyje-Svratka Valley (Dyjsko-svratecký úval), the Upper Morava Valley (Hornomoravský úval) and the Lower Morava Valley (Dolnomoravský úval). The first two form the westernmost part of the Outer Subcarpathia; the last is the northernmost part of the Vienna Basin. The valleys surround the low range of Central Moravian Carpathians. The highest mountains of Moravia are situated on its northern border in Hrubý Jeseník; the highest peak is Praděd (1491 m). Second highest is the massif of Králický Sněžník (1424 m) the third are the Moravian-Silesian Beskids at the extreme east, with Smrk (1278 m), and then south from here Javorníky (1072). The White Carpathians along the southeastern border rise up to 970 m at Velká Javořina. The Bohemian-Moravian Highlands on the west reach 837 m at Javořice.

The river system of Moravia is very cohesive[clarification needed], as the region's border closely follows the watershed of the Morava river, and thus almost the entire area is drained exclusively by a single stream. Easily the Morava's biggest tributaries are Thaya (Dyje) from the right (or west) and Bečva (east). The Morava and the Thaya meet at the southernmost and lowest (148 m) point of Moravia. Small peripheral parts of Moravia belong to the catchment areas of Elbe, Váh and especially Oder (the northeast). The watershed line running along Moravia's border from west to north and east is part of the European Watershed. For centuries, there have been plans to build a waterway across Moravia to join the Danube and Oder river systems, using the natural route through the Moravian Gate.[15][16]

History

[edit]Pre-history

[edit]

Evidence of the presence of members of the human genus, Homo, dates back more than 600,000 years in the paleontological area of Stránská skála.[14]

Attracted by suitable living conditions, early modern humans had settled in the region by the Paleolithic period. The Předmostí archeological (Cro-Magnon) site in Moravia is dated to between 27,000 and 24,000 years old.[17][18] Caves in Moravian Karst were used by mammoth hunters. Venus of Dolní Věstonice, the oldest ceramic figure in the world,[19][20] was found in the excavation of Dolní Věstonice by Karel Absolon.[21] In November 2024 a new discovery was made on the outskirts of Brno, where bones of at least three mammoths were found along with other animals and human stone tools dating back 15,000 years.[22]

Bronze Age

[edit]During the Bronze Age, people of various cultures settled in Moravia. Notably the Nitra culture which emerged from the tradition of the Neolithic Corded Ware culture and was spread in western Slovakia (hence the name, derived from Slovak river Nitra), eastern Moravia and southern Poland. The largest burial site (400 graves) of Nitra culture in Moravia was discovered in Holešov in the 1960s.[23] The most recent discovery unearthed 2 settlements and two burial grounds (with total 130 graves) near Olomouc, one of them of the Nitra culture dating between the years 2100-1800 BC and was published in October 2024.[24] This discovery adds up to other Bronze Age discoveries such as a sword found near the city of Přerov, the sword was called ‘the Excalibur of the Late Bronze Age’.[25]

Roman era

[edit]Around 60 BC, the Celtic Volcae people withdrew from the region and were succeeded by the Germanic Quadi. Some of the events of the Marcomannic Wars took place in Moravia in AD 169–180. After the war exposed the weakness of Rome's northern frontier, half of the Roman legions (16 out of 33) were stationed along the Danube. In response to increasing numbers of Germanic settlers in frontier regions like Pannonia, Dacia, Rome established two new frontier provinces on the left shore of the Danube, Marcomannia and Sarmatia, including today's Moravia and western Slovakia.

In the 2nd century AD, a Roman fortress[26][27] stood on the vineyards hill known as German: Burgstall and Czech: Hradisko ("hillfort"), situated above the former village Mušov and above today's beach resort at Pasohlávky. During the reign of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the 10th Legion was assigned to control the Germanic tribes who had been defeated in the Marcomannic Wars.[28] In 1927, the archeologist Gnirs, with the support of president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, began research on the site, located 80 km from Vindobona and 22 km to the south of Brno. The researchers found remnants of two masonry buildings, a praetorium[29] and a balneum ("bath"), including a hypocaustum. The discovery of bricks with the stamp of the Legio X Gemina and coins from the period of the emperors Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius and Commodus facilitated dating of the locality.

Ancient Moravia

[edit]

A variety of Germanic and major Slavic tribes crossed through Moravia during the Migration Period before Slavs established themselves in the 6th century AD. At the end of the 8th century, the Moravian Principality came into being in present-day south-eastern Moravia, Záhorie in south-western Slovakia and parts of Lower Austria. In 833 AD, this became the state of Great Moravia[30] with the conquest of the Principality of Nitra (present-day Slovakia). Their first king was Mojmír I (ruled 830–846). Louis the German invaded Moravia and replaced Mojmír I with his nephew Rastiz who became St. Rastislav.[31] St. Rastislav (846–870) tried to emancipate his land from the Carolingian influence, so he sent envoys to Rome to get missionaries to come. When Rome refused he turned to Constantinople to the Byzantine emperor Michael. The result was the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius who translated liturgical books into Slavonic, which had lately been elevated by the Pope to the same level as Latin and Greek. Methodius became the first Moravian archbishop, the first archbishop in Slavic world, but after his death the German influence again prevailed and the disciples of Methodius were forced to flee. Great Moravia reached its greatest territorial extent in the 890s under Svatopluk I. At this time, the empire encompassed the territory of the present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia, the western part of present Hungary (Pannonia), as well as Lusatia in present-day Germany and Silesia and the upper Vistula basin in southern Poland. After Svatopluk's death in 895, the Bohemian princes defected to become vassals of the East Frankish ruler Arnulf of Carinthia, and the Moravian state ceased to exist after being overrun by invading Magyars in 907.[32][33]

Union with Bohemia

[edit]Following the defeat of the Magyars by Emperor Otto I at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, Otto's ally Boleslaus I, the Přemyslid ruler of Bohemia, took control over Moravia. Bolesław I Chrobry of Poland annexed Moravia in 999, and ruled it until 1019,[34] when the Přemyslid prince Bretislaus recaptured it. Upon his father's death in 1034, Bretislaus became the ruler of Bohemia. In 1055, he decreed that Bohemia and Moravia would be inherited together by primogeniture, although he also provided that his younger sons should govern parts (quarters) of Moravia as vassals to his oldest son.

Throughout the Přemyslid era, junior princes often ruled all or part of Moravia from Olomouc, Brno or Znojmo, with varying degrees of autonomy from the ruler of Bohemia. Dukes of Olomouc often acted as the "right hand" of Prague dukes and kings, while Dukes of Brno and especially those of Znojmo were much more insubordinate. Moravia reached its height of autonomy in 1182, when Emperor Frederick I elevated Conrad II Otto of Znojmo to the status of a margrave,[35] immediately subject to the emperor, independent of Bohemia. This status was short-lived: in 1186, Conrad Otto was forced to obey the supreme rule of Bohemian duke Frederick. Three years later, Conrad Otto succeeded to Frederick as Duke of Bohemia and subsequently canceled his margrave title. Nevertheless, the margrave title was restored in 1197 when Vladislaus III of Bohemia resolved the succession dispute between him and his brother Ottokar by abdicating from the Bohemian throne and accepting Moravia as a vassal land of Bohemian (i.e., Prague) rulers. Vladislaus gradually established this land as Margraviate, slightly administratively different from Bohemia. After the Battle of Legnica, the Mongols carried their raids into Moravia.

The main line of the Přemyslid dynasty became extinct in 1306, and in 1310 John of Luxembourg became Margrave of Moravia and King of Bohemia. In 1333, he made his son Charles the next Margrave of Moravia (later in 1346, Charles also became the King of Bohemia). In 1349, Charles gave Moravia to his younger brother John Henry who ruled in the margraviate until his death in 1375, after him Moravia was ruled by his oldest son Jobst of Moravia who was in 1410 elected the Holy Roman King but died in 1411 (he is buried with his father in the Church of St. Thomas in Brno – the Moravian capital from which they both ruled). Moravia and Bohemia remained within the Luxembourg dynasty of Holy Roman kings and emperors (except during the Hussite wars), until inherited by Albert II of Habsburg in 1437.

After his death followed the interregnum until 1453; land (as the rest of lands of the Bohemian Crown) was administered by the landfriedens (landfrýdy). The rule of young Ladislaus the Posthumous subsisted only less than five years and subsequently (1458) the Hussite George of Poděbrady was elected as the king. He again reunited all Czech lands (then Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Upper & Lower Lusatia) into one-man ruled state. In 1466, Pope Paul II excommunicated George and forbade all Catholics (i.e. about 15% of population) from continuing to serve him. The Hungarian crusade followed and in 1469 Matthias Corvinus conquered Moravia and proclaimed himself (with assistance of rebelling Bohemian nobility) as the king of Bohemia.

The subsequent 21-year period of a divided kingdom was decisive for the rising awareness of a specific Moravian identity, distinct from that of Bohemia. Although Moravia was reunited with Bohemia in 1490 when Vladislaus Jagiellon, king of Bohemia, also became king of Hungary, some attachment to Moravian "freedoms" and resistance to government by Prague continued until the end of independence in 1620. In 1526, Vladislaus' son Louis died in battle and the Habsburg Ferdinand I was elected as his successor.

-

Bohemia and Moravia in the 12th century

-

Church of St. Thomas in Brno, mausoleum of Moravian branch House of Luxembourg, rulers of Moravia; and the old governor's palace, a former Augustinian abbey

-

12th century Romanesque St. Procopius Basilica in Třebíč

Habsburg rule (1526–1918)

[edit]

After the death of King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia in 1526, Ferdinand I of Austria was elected King of Bohemia and thus ruler of the Crown of Bohemia (including Moravia). The epoch 1526–1620 was marked by increasing animosity between Catholic Habsburg kings (emperors) and the Protestant Moravian nobility (and other Crowns') estates. Moravia,[38] like Bohemia, was a Habsburg possession until the end of World War I. In 1573 the Jesuit University of Olomouc was established; this was the first university in Moravia. The establishment of a special papal seminary, Collegium Nordicum, made the University a centre of the Catholic Reformation and effort to revive Catholicism in Central and Northern Europe. The second largest group of students were from Scandinavia.

Brno and Olomouc served as Moravia's capitals until 1641. As the only city to successfully resist the Swedish invasion, Brno become the sole capital following the capture of Olomouc. The Margraviate of Moravia had, from 1348 in Olomouc and Brno, its own Diet, or parliament, zemský sněm (Landtag in German), whose deputies from 1905 onward were elected separately from the ethnically separate German and Czech constituencies. The oldest surviving theatre building in Central Europe, the Reduta Theatre, was established in 17th-century Moravia.

From 1599 to 1711, Moravia was frequently subjected to raids by the Ottoman Empire and its vassals (especially the Tatars and Transylvania). Overall, hundreds of thousands were enslaved whilst tens of thousands were killed.[39][40]

In 1740, Moravia was invaded by Prussian forces under Frederick the Great, and Olomouc was forced to surrender on 27 December 1741. A few months later, the Prussians were repelled, mainly because of their unsuccessful siege of Brno in 1742. In 1758, Olomouc was besieged by Prussians again, but this time its defenders forced the Prussians to withdraw following the Battle of Domstadtl. In 1777, a new Moravian bishopric was established in Brno, and the Olomouc bishopric was elevated to an archbishopric.[41] In 1782, the Margraviate of Moravia was merged with Austrian Silesia into Moravia-Silesia, with Brno as its capital. Moravia became a separate crown land of Austria again in 1849,[42][43] and then became part of Cisleithanian Austria-Hungary after 1867. According to Austro-Hungarian census of 1910 the proportion of Czechs in the population of Moravia at the time (2,622,000) was 71.8%, while the proportion of Germans was 27.6%.[44]

-

Administrative division of Moravia as crown land of Austria in 1893

20th century

[edit]

Following the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, Moravia became part of Czechoslovakia. As one of the five lands of Czechoslovakia, it had restricted autonomy. In 1928 Moravia ceased to exist as a territorial unity and was merged with Czech Silesia into the Moravian-Silesian Land (yet with the natural dominance of Moravia). By the Munich Agreement (1938), the southwestern and northern peripheries of Moravia, which had a German-speaking majority, were annexed by Nazi Germany, and during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia (1939–1945), the remnant of Moravia was an administrative unit within the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

During World War II, the Germans operated multiple forced labour camps in the region, including several subcamps of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp for Allied POWs,[45] a subcamp of the Auschwitz concentration camp in Brno for mostly Polish prisoners,[46] and a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp in Bílá Voda for Jewish women.[47] The occupiers also established several POW camps, including Heilag VIII-H, Oflag VIII-F and Oflag VIII-H, for French, British, Belgian and other Allied POWs in the region.[48]

In 1945 after the Allied defeat of Germany and the end of World War II, the German minority was expelled to Germany and Austria in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement. The Moravian-Silesian Land was restored with Moravia as part of it and towns and villages that were left by the former German inhabitants, were re-settled by Czechs, Slovaks and reemigrants.[49] In 1949 the territorial division of Czechoslovakia was radically changed, as the Moravian-Silesian Land was abolished and Lands were replaced by "kraje" (regions), whose borders substantially differ from the historical Bohemian-Moravian border, so Moravia politically ceased to exist after more than 1100 years (833–1949) of its history. Although another administrative reform in 1960 implemented (among others) the North Moravian and the South Moravian regions (Severomoravský and Jihomoravský kraj), with capitals in Ostrava and Brno respectively, their joint area was only roughly alike the historical state and, chiefly, there was no land or federal autonomy, unlike Slovakia.

After the fall of the Soviet Union and the whole Eastern Bloc, the Czechoslovak Federal Assembly condemned the cancellation of Moravian-Silesian land and expressed "firm conviction that this injustice will be corrected" in 1990. However, after the breakup of Czechoslovakia into Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993, Moravian area remained integral to the Czech territory, and the latest administrative division of Czech Republic (introduced in 2000) is similar to the administrative division of 1949. Nevertheless, the federalist or separatist movement in Moravia is completely marginal.

The centuries-lasting historical Bohemian-Moravian border has been preserved up to now only by the Czech Roman Catholic Administration, as the Ecclesiastical Province of Moravia corresponds with the former Moravian-Silesian Land. The popular perception of the Bohemian-Moravian border's location is distorted by the memory of the 1960 regions (whose boundaries are still partly in use).

-

Jan Černý, president of Moravia in 1922–1926, later also Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia

-

A general map of Moravia in the 1920s

-

In 1928, Moravia was merged into Moravia-Silesia, one of four lands of Czechoslovakia, together with Bohemia, Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus.

Economy

[edit]An area in South Moravia, around Hodonín and Břeclav, is part of the Viennese Basin. Petroleum and lignite are found there in abundance. The main economic centres of Moravia are Brno, Olomouc, Zlín, and Ostrava lying directly on the Moravian–Silesian border. As well as agriculture in general, Moravia is noted for its viticulture; it contains 94% of the Czech Republic's vineyards and is at the centre of the country's wine industry. Wallachia has at least a 400-year-old tradition of slivovitz making.[50]

The Czech automotive industry also played a significant role in Moravia's economy in the 20th century; the factories of Wikov in Prostějov and Tatra in Kopřivnice produced many automobiles.

Moravia is also the centre of the Czech firearm industry, as the vast majority of Czech firearms manufacturers (e.g. CZUB, Zbrojovka Brno, Czech Small Arms, Czech Weapons, ZVI, Great Gun) are found in Moravia. Almost all the well-known Czech sporting, self-defence, military, and hunting firearms are made in Moravia. Meopta rifle scopes are of Moravian origin. The original Bren gun was conceived here, as were the assault rifles the CZ-805 BREN and Sa vz. 58, and the handguns CZ 75 and ZVI Kevin (also known as the "Micro Desert Eagle").

The Zlín Region hosts several aircraft manufacturers, namely Let Kunovice (also known as Aircraft Industries, a.s.), ZLIN AIRCRAFT a.s. Otrokovice (formerly known under the name Moravan Otrokovice), Evektor-Aerotechnik, and Czech Sport Aircraft. Sport aircraft are also manufactured in Jihlava by Jihlavan Airplanes/Skyleader.

Aircraft production in the region started in the 1930s; after a period of low production post-1989, there have been signs of recovery post-2010, and production is expected to grow from 2013 onwards.[51]

Companies with operations in Brno include Gen Digital, which maintains one of its headquarters there and continues to use the brand AVG Technologies,[52] as well as Kyndryl (Client Innovation Centre),[53][54] AT&T, and Honeywell (Global Design Center).[55] Other significant companies include Siemens,[56] Red Hat (Czech headquarters),[57] and an office of Zebra Technologies.[58]

In recent years, Brno's economy has seen growth in the quaternary sector, focusing on science, research, and education. Notable projects include AdMaS (Advanced Materials, Structures, and Technologies) and CETOCOEN (Center for Research on Toxic Substances in the Environment).[59]

-

The Tatra 77 (1934)

-

WIKOV Supersport (1931)

-

Thonet No. 14 chair

-

The speed train Tatra M 290.0 Slovenská strela 1936

-

Zlín XIII aircraft on display at the National Technical Museum in Prague

-

Zetor 25A tractor

-

Electron microscope Brno

-

Aeroplane L 410 NG by Let Kunovice

-

Precise rifle scope by MeOpta

-

The (modern) BREN gun M 2 11

-

The modern EVO 2 tram

-

Diesel railway coach class Bfhpvee295

Machinery industry

[edit]The machinery industry has been the most important industrial sector in the region, especially in South Moravia, for many decades. The main centres of machinery production are Brno (Zbrojovka Brno, Zetor, První brněnská strojírna, Siemens), Blansko (ČKD Blansko, Metra), Kuřim (TOS Kuřim), Boskovice (Minerva, Novibra) and Břeclav (Otis Elevator Company). A number of other, smaller machinery and machine parts factories, companies, and workshops are spread over Moravia.

Electrical industry

[edit]The beginnings of the electrical industry in Moravia date back to 1918. The biggest centres of electrical production are Brno (VUES, ZPA Brno, EM Brno), Drásov, Frenštát pod Radhoštěm, and Mohelnice (currently Siemens).

Cities and towns

[edit]Cities

[edit]- Brno (401,000 inhabitants) former land capital and nowadays capital of South Moravian Region; industrial, judicial, educational and research centre; railway and motorway junction

- Ostrava (285,000; central part, Moravská Ostrava, lies historically in Moravia, most of the outskirts are in Czech Silesia), capital of Moravian-Silesian Region, centre of heavy industry

- Olomouc (102,000), capital of Olomouc Region, medieval land capital, seat of Roman Catholic archbishop, cultural centre of Hanakia and Central Moravia

- Zlín (74,000), capital of Zlín Region, modern city developed after World War I by the Bata Shoes company

- Jihlava (54,000; mostly in Moravia, northwestern periphery lies in Bohemia), capital of Vysočina Region, centre of the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands

- Frýdek-Místek (54,000), twin-city lying directly on the old Moravian-Silesian border (the western part, Místek, is Moravian), in the industrial area around Ostrava

- Prostějov (44,000), former centre of clothing and fashion industry, birthplace of Edmund Husserl

- Přerov (42,000), important railway hub and archeological site (Předmostí)

Towns

[edit]- Třebíč (35,000), located in the Highlands, with exceptionally preserved Jewish quarter

- Znojmo (34,000), historical and cultural centre of southwestern Moravia

- Kroměříž (28,000), historical town in southern Hanakia

- Vsetín (25,000), centre of the Moravian Wallachia

- Šumperk (25,000), centre of the north of Moravia, at the foot of Hrubý Jeseník

- Uherské Hradiště (25,000), cultural centre of the Moravian Slovakia

- Břeclav (25,000), important railway hub in the very south of Moravia

- Hodonín (24,000), another town in the Moravian Slovakia, the birthplace of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

- Nový Jičín (23,000), historical town with hatting industry

- Valašské Meziříčí (23,000), centre of chemical industry in Moravian Wallachia

- Kopřivnice (22,000), centre of automotive industry (Tatra), south from Ostrava

- Žďár nad Sázavou (21,000), industrial town in the Highlands, near the border with Bohemia

- Vyškov (20,000), local centre at a motorway junction halfway between Brno and Olomouc

- Blansko (20,000), industrial town north from Brno, at the foot of the Moravian Karst

People

[edit]

The Moravians are generally a Slavic ethnic group who speak various (generally more archaic) dialects of Czech. Before the expulsion of Germans from Moravia the Moravian German minority also referred to themselves as "Moravians" (Mährer). Those expelled and their descendants continue to identify as Moravian. [60] Some Moravians assert that Moravian is a language distinct from Czech; however, their position is not widely supported by academics and the public.[61][62][63][64] Some Moravians identify as an ethnically distinct group; the majority consider themselves to be ethnically Czech. In the census of 1991 (the first census in history in which respondents were allowed to claim Moravian nationality), 1,362,000 (13.2%) of the Czech population identified as being of Moravian nationality (or ethnicity). In some parts of Moravia (mostly in the centre and south), majority of the population identified as Moravians, rather than Czechs. In the census of 2001, the number of Moravians had decreased to 380,000 (3.7% of the country's population).[65] In the census of 2011, this number rose to 522,474 (4.9% of the Czech population).[66][67]

Moravia historically had a large minority of ethnic Germans, some of whom had arrived as early as the 13th century at the behest of the Přemyslid dynasty. Germans continued to come to Moravia in waves, culminating in the 18th century. They lived in the main city centres and in the countryside along the border with Austria (stretching up to Brno) and along the border with Silesia at Jeseníky, and also in two language islands, around Jihlava and around Moravská Třebová. After World War II, the Czechoslovak government almost fully expelled them in retaliation for their support of Nazi Germany's invasion and dismemberment of Czechoslovakia (1938–1939) and subsequent German war crimes (1938–1945) towards the Czech, Moravian, and Jewish populations.

Moravians

[edit]

Notable people from Moravia include:

- Anton Pilgram (1450–1516), architect, sculptor and woodcarver

- Jan Ámos Komenský (Comenius) (1592–1670), educator and theologian, last bishop of Unity of the Brethren

- Georg Joseph Camellus (1661–1706), Jesuit missionary to the Philippines, pharmacist and botanist

- David Zeisberger (1717–1807) Moravian missionary to the Leni Lenape, "Apostle to the Indians"

- Georgius Prochaska (1749–1820), ophthalmologist and physiologist

- František Palacký (1798–1876), historian and politician, "The Father of the Czech nation"

- Gregor Mendel (1822–1884), founder of genetics

- Ernst Mach (1838–1916), physicist and philosopher

- Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937), philosopher and politician, first president of Czechoslovakia

- Leoš Janáček (1854–1928), composer

- Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), founder of psychoanalysis

- Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), philosopher

- Alfons Mucha (1860–1939), painter

- Zdeňka Wiedermannová-Motyčková (1868–1915), women's rights activist

- Adolf Loos (1870–1933), architect

- Karl Renner (1870–1950), Austrian statesman, co-founder of Friends of Nature movement

- Tomáš Baťa (1876–1932), entrepreneur, founder of Bata Shoes company

- Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950), economist and political scientist

- Marie Jeritza (1887–1982), soprano singer

- Hans Krebs (1888–1947), Nazi SS officer executed for treason

- Ludvík Svoboda (1895–1979), army general, president of Czechoslovakia

- Klement Gottwald (1896–1953), politician, president of Czechoslovakia

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957), composer

- George Placzek (1905–1955), physicist, participant in Manhattan Project

- Kurt Gödel (1906–1978), theoretical mathematician

- Oskar Schindler (1908–1974), German industrialist credited with saving almost 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust

- Jan Kubiš (1913–1942), paratrooper who assassinated Nazi despot R. Heydrich

- Bohumil Hrabal (1914–1997), writer

- Thomas J. Bata (1914–2008), entrepreneur, son of Tomáš Baťa and former head of the Bata shoe company

- Emil Zátopek (1922–2000), long-distance runner, Olympic winner

- Karel Reisz (1926–2002), filmmaker

- Milan Kundera (1929–2023), writer

- Václav Nedomanský (born 1944), ice hockey player

- Karel Kryl (1944–1994), poet and protest singer-songwriter

- Karel Loprais (1949–2021), truck race driver, multiple winner of the Dakar Rally

- Ivana Trump (1949–2022), socialite and business magnate, former wife of Donald Trump

- Ivan Lendl (born 1959), tennis player

- Petr Nečas (born 1964), politician, Czech Prime Minister 2010–2013

- Paulina Porizkova (born 1965), model, actress and writer

- Jana Novotná (1968–2017), tennis player

- Jiří Šlégr (born 1971), ice hockey player

- Bohuslav Sobotka (born 1971), politician, Czech Prime Minister 2014–2017

- Magdalena Kožená (born 1973), mezzo-soprano

- Markéta Irglová (born 1988), singer-songwriter, Academy Award winner

- Petra Kvitová (born 1990), tennis player

- Adam Ondra (born 1993), rock climber

- Barbora Krejčíková (born 1996), tennis player

Ethnographic regions

[edit]Moravia can be divided on dialectal and lore basis into several ethnographic regions of comparable significance. In this sense, it is more heterogenous than Bohemia. Significant parts of Moravia, usually those formerly inhabited by the German speakers, are dialectally indifferent, as they have been resettled by people from various Czech (and Slovak) regions.

The principal cultural regions of Moravia are:

- Hanakia (Haná) in the central and northern part

- Lachia (Lašsko) in the northeastern tip

- Highlands (Horácko) in the west

- Moravian Slovakia (Slovácko) in the southeast

- Moravian Wallachia (Valašsko) in the east

Places of interest

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

World Heritage Sites

[edit]- Gardens and Castle at Kroměříž

- Historic Centre of Telč

- Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc

- Jewish Quarter and St Procopius' Basilica in Třebíč

- Lednice-Valtice Cultural Landscape

- Pilgrimage Church of St John of Nepomuk at Zelená Hora

- Tugendhat Villa in Brno

Other

[edit]- Hranice Abyss, the deepest known underwater cave in the world

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /məˈreɪviə/ mə-RAY-vee-ə,[6] UK also /mɒˈ-/ morr-AY-,[7] US also /mɔːˈ-, moʊˈ-/ mor-AY-, moh-RAY-.[7][8]

- ^ Including Moravian enclaves in Silesia.[10][11]

References

[edit]- ^ Royal Frankish Annals (year 822), pp. 111–112.

- ^ Morava, Iniciativa Naša. "Fakta o Moravě – Naša Morava".

- ^ Bowlus, Charles R. (2009). "Nitra: when did it become a part of the Moravian realm? Evidence in the Frankish sources". Early Medieval Europe. 17 (3): 311–328. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00279.x. S2CID 161655879.

- ^ a b "Encyklopedie dějin města Brna". 2004.

- ^ a b "Population of Municipalities – 1 January 2024". Czech Statistical Office. 17 May 2024.

- ^ "Moravia". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.; "Moravia". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Moravia". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Moravia". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ (Czech: Morava [ˈmorava] ⓘ; German: Mähren [ˈmɛːʁən] ⓘ)

- ^ "Dodatek I. Přehled Moravy a Slezska podle žup". Statistický lexikon obcí v republice Československé. Morava a Slezsko (in Czech). Prague: Státní úřad statistický. 1924. p. 133.

- ^ "Dodatek IV. Moravské enklávy ve Slezsku". Statistický lexikon obcí v republice Československé. Morava a Slezsko (in Czech). Prague: Státní úřad statistický. 1924. p. 138.

- ^ a.s., Economia (18 February 2000). "Jsem Moravan?".

- ^ "Říkáte celé ČR Čechy? Pro Moraváky jste ignorant". 8 February 2010.

- ^ a b Antón, Mauricio; Galobart, Angel; Turner, Alan (May 2005). "Co-existence of scimitar-toothed cats, lions and hominins in the European Pleistocene. Implications of the post-cranial anatomy of Homotherium latidens (Owen) for comparative palaeoecology". Quaternary Science Reviews. 24 (10–11): 1287–1301. Bibcode:2005QSRv...24.1287A. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.09.008.

- ^ Administrator. "About the multipurpose water corridor Danube-Oder-Elbe". Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Klimo, Emil; Hager, Herbert (2000). The Floodplain Forests in Europe: Current Situation and Perspectives (European Forest Institute research reports). Leiden: Brill. p. 48. ISBN 9789004119581.

- ^ Velemínskáa, J.; Brůžekb, J.; Velemínskýd, P.; Bigonia, L.; Šefčákováe, A.; Katinaf, F. (2008). "Variability of the Upper Palaeolithic skulls from Předmostí near Přerov (Czech Republic): Craniometric comparison with recent human standards". Homo. 59 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2007.12.003. PMID 18242606.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (7 October 2011). "Prehistoric dog found with mammoth bone in mouth". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Jonathan Jones: Carl Andre on notoriety and a 26,000-year-old portrait – the week in art. The Guardian 25 January 2013

- ^ "Dolni Vestonice and Pavlov sites".

- ^ Oldest homes were made of mammoth bone. The Times 29.8.2005

- ^ "Skeletal remains of three mammoths discovered in Brno city centre". Radio Prague International. 11 November 2024. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ Kaňáková, Ludmila; Bátora, Jozef; Nosek, Vojtěch (February 2020). "Use-wear and ballistic analysis of arrowheads from the burial ground of Nitra culture in Holešov–Zdražilovska, Moravia". Journal of Archaeological Science. 29. Bibcode:2020JArSR..29j2126K. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102126. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ "Archaeologists discover unique Early Bronze Age burial site near Olomouc". Radio Prague International. 21 October 2024. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Moravia's Excalibur: Bronze-Age sword unearthed near Přerov". Radio Prague International. 25 October 2024. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ "Detašované pracoviště Dolní Dunajovice – Hradisko u Mušova".

- ^ "Opevnění – Detašované pracoviště Dolní Dunajovice, AÚ AV ČR Brno, v. v. i."

- ^ Hanel, Norbert; Cerdán, Ángel Morillo; Hernández, Esperanza Martín (1 January 2009). Limes XX: Estudios sobre la frontera romana (Roman frontier studies). Editorial CSIC – CSIC Press. ISBN 9788400088545 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Lázeňská a obytná budova – Detašované pracoviště Dolní Dunajovice, AÚ AV ČR Brno, v. v. i."

- ^ Florin Kurta. The history and archaeology of Great Moravia: an introduction. in: "Early Medieval Europe", 2009 volume 17 (3)

- ^ Reuter, Timothy. (1991). Germany in the Early Middle Ages, London: Longman, page 82

- ^ Štefan, Ivo (2011). "Great Moravia, Statehood and Archaeology: The "Decline and Fall" of One Early Medieval Polity". In Macháček, Jiří; Ungerman, Šimon (eds.). Frühgeschichtliche Zentralorte in Mitteleuropa. Bonn: Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt. pp. 333–354. ISBN 978-3-7749-3730-7. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- ^ The exact dating of the conquest of Moravia by Bohemian dukes is uncertain. Czech and some Slovak historiographers suggest the year 1019, while Polish, German and other Slovak historians suggest 1029, during the rule of Boleslaus' son, Mieszko II Lambert.

- ^ There are no primary testimonies about creating a margraviate (march) as distinct political unit

- ^ Svoboda, Zbyšek; Fojtík, Pavel; Exner, Petr; Martykán, Jaroslav (2013). "Odborné vexilologické stanovisko k moravské vlajce" (PDF). Vexilologie. Zpravodaj České vexilologické společnosti, o.s. č. 169. Brno: Česká vexilologická společnost. pp. 3319, 3320.

- ^ Pícha, František (2013). "Znaky a prapory v kronice Ottokara Štýrského" (PDF). Vexilologie. Zpravodaj České vexilologické společnosti, o.s. č. 169. Brno: Česká vexilologická společnost. pp. 3320–3324.

- ^ Evan Rail (23 September 2011). The Castles of Moravia. NYT 23.9.2011

- ^ Košťálová, Petra (2022). Chmurski, Mateusz; Dmytrychyn, Irina (eds.). "Contested Landscape: Moravian Wallachia and Moravian Slovakia. An Imagology Study on the Ottoman Border Narrative". Revue des études slaves. 93 (1). OpenEdition: 110. doi:10.4000/res.5138. ISSN 2117-718X. JSTOR 27185958.

- ^ Lánové rejstříky (1656–1711) Archived 12 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Czech)

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Moravia".

- ^ Czechoslovakia: A Country Study. US Army. 1898. p. 27.

- ^ "Moravia | historical region, Europe | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Hans Chmelar: Höhepunkte der österreichischen Auswanderung. Die Auswanderung aus den im Reichsrat vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern in den Jahren 1905–1914. (= Studien zur Geschichte der österreichisch-ungarischen Monarchie. Band 14) Kommission für die Geschichte der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1974, ISBN 3-7001-0075-2, p. 109.

- ^ "Working Parties". Lamsdorf.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Brünn". Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Subcamps of KL Gross-Rosen". Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 207, 257, 259. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ Bičík, Ivan; Štěpánek, Vít (1994). "Post-war changes of the land-use structure in Bohemia and Moravia: Case study Sudetenland". GeoJournal. 32 (3): 253–259. Bibcode:1994GeoJo..32..253B. doi:10.1007/BF01122117. S2CID 189878438.

- ^ "Jelínek's 400-Year Tradition of Making Slivovitz Bears Fruit in the U.S." OU Kosher Certification. 5 October 2010.

- ^ "Leteckou výrobu v Česku čeká v roce 2013 růst. Pomůže modernizace L-410 (Czech aircraft production expected to grow in 2013)". Hospodářské noviny IHNED. 2012. ISSN 1213-7693.

- ^ "AVG Antivirus and Security Software – Contact us". Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Kyndryl Client Center, s.r.o." Faculty of Information Technology, Brno University of Technology. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "IBM Governmental Programs – Delivery Centre Central Eastern Europe in Brno". IBM. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Honeywell Global Design Center Brno". Honeywell Czech Republic. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Brno". Siemens (in Czech). Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Red Hat Europe". Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "MOTOROLA – Technology Park Brno". Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ univerzita, Masarykova. "O projektu". MUNI | RECETOX (in Czech). Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Bill Lehane: ČSÚ (Czech statistical office) plays down census disputes – Campaign want to include Moravian language in count (Moravian identity). The Prague Post 9.3.2011 20

- ^ Kolínková, Eliška (26 December 2008). "Číšník tvoří spisovnou moravštinu". Mladá fronta DNES (in Czech). iDnes. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ Zemanová, Barbora (12 November 2008). "Moravané tvoří spisovnou moravštinu". Brněnský Deník (in Czech). denik.cz. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ O spisovné moravštině a jiných "malých" jazycích (Naše řeč 5, ročník 83/2000) (in Czech)

- ^ Kolínková, Eliška (30 December 2008). "Amatérský jazykovědec prosazuje moravštinu jako nový jazyk". Mladá fronta DNES (in Czech). iDnes. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ Robert B. Kaplan; Richard B. Baldauf (1 January 2005). Language Planning and Policy in Europe. Multilingual Matters. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-1-85359-813-5.

- ^ Tesser, Lynn (14 May 2013). Ethnic Cleansing and the European Union: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Security, Memory and Ethnography. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 213–. ISBN 978-1-137-30877-1.

- ^ Ibp, Inc (10 September 2013). Czech Republic Mining Laws and Regulations Handbook - Strategic Information and Basic Laws. Int'l Business Publications. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-1-4330-7727-2.

Further reading

[edit]- The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful ... (1877), volume 15. London, Charles Knight. Moravia. pp. 397–398.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica (2003). Chicago, New Delhi, Paris, Seoul, Sydney, Taipei, Tokyo. Volume 8. p. 309. Moravia. ISBN 0-85229 961-3.

- Filip, Jan (1964). The Great Moravia exhibition. ČSAV (Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences).

- Galuška, Luděk, Mitáček Jiří, Novotná, Lea (eds.) (2010) Treausures of Moravia: story of historical land. Brno, Moravian Museum. ISBN 978-80-7028-371-4.

- National Geographic Society. Wonders of the Ancient World; National Geographic Atlas of Archaeology, Norman Hammond, consultant, Nat'l Geogr. Soc., (multiple staff authors), (Nat'l Geogr., R. H. Donnelley & Sons, Willard, OH), 1994, 1999, Reg or Deluxe Ed., 304 pp. Deluxe ed. photo (p. 248): "Venus, Dolni Věstonice, 24,000 B.C." In section titled: "The Potter's Art", pp. 246–253.

- Dekan, Jan (1981). Moravia Magna: The Great Moravian Empire, Its Art and Time, Minneapolis: Control Data Arts. ISBN 0-89893-084-7.

- Hugh, Agnew (2004). The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown.Hoower Press, Stanford. ISBN 0-8179-4491-5.

- Poláček, Lumír (2014). "Great Moravian sacral architecture – new research, new questions". The Cyril and Methodius Mission and Europe: 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia. Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. pp. 66–73. ISBN 978-80-86023-51-9. OS LG 2023-08-18.

- Róna-Tas, András (1999) Hungarians & Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History translated by Nicholas Bodoczky, Central European University Press, Budapest, ISBN 963-9116-48-3.

- Wihoda, Martin (2015), Vladislaus Henry: The Formation of Moravian Identity. Brill Publishers ISBN 9789004250499.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (1996) A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival St. Martin's Press, New York, ISBN 0-312-16125-5.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus De Administrando Imperio edited by Gy. Moravcsik, translated by R. J. H. Jenkins, Dumbarton Oaks Edition, Washington, D.C. (1993)

- Hlobil, Ivo, Daniel, Ladislav (2000), The last flowers of the middle ages: from the gothic to the renaissance in Moravia and Silesia. Olomouc/Brno, Moravian Galery, Muzeum umění Olomouc ISBN 9788085227406

- David, Jiří (2009). "Moravian estatism and provincial councils in the second half of the 17th century". Folia historica Bohemica. 1 24: 111–165. ISSN 0231-7494.

- Svoboda, Jiří A. (1999), Hunters between East and West: the paleolithic of Moravia. New York: Plenum Press, ISSN 0231-7494.

- Absolon, Karel (1949), The diluvial anthropomorphic statuettes and drawings, especially the so-called Venus statuettes, discovered in Moravia New York, Salmony 1949. ISSN 0231-7494.

- Musil, Rudolf (1971), G. Mendel's Discovery and the Development of Agricultural and Natural Sciences in Moravia. Brno, Moravian Museum.

- Šimsa, Martin (2009), Open-Air Museum of Rural Architecture in South-East Moravia. Strážnice, National Institute of Folk Culture. ISBN 9788087261194.

- Miller, Michael R. (2010), The Jews of Moravia in the Age of Emancipation, Cover of Rabbis and Revolution edition. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804770569.

- Bata, Thomas J. (1990), Bata: Shoemaker to the World. Stoddart Publishers Canada. ISBN 9780773724167.

- Knox, Brian (1962), Bohemia and Moravia: An Architectural Companion. Faber & Faber.

External links

[edit]- Moravské zemské muzeum official website

- Moravian gallery official website

- Moravian library official website

- Moravian land archive official website Archived 26 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Czech)

- Province of Moravia – Czech Catholic Church – official website

- Welcome to the 2nd largest city of the CR (in Czech, English, and German)

- Welcome to Olomouc, city of good cheer... (in Czech, English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Polish, Russian, Japanese, and Chinese)

- Znojmo – City of Virtue Archived 8 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine (in Czech, English, and German)

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Moravia". New International Encyclopedia. Vol. XIII. 1905.

- "Moravia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XVI (9th ed.). 1883.

- "Moravia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Moravia". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. 1911.

Moravia

View on GrokipediaMoravia is a historical region in Central Europe comprising the eastern third of the Czech Republic, centered on the Morava River basin and bounded by Bohemia to the west, the Czech Republic's Silesian portion to the north, Slovakia to the east, and Austria to the south.[1][2] It forms one of the three traditional Czech lands, alongside Bohemia and Czech Silesia, with borders largely unchanged since the Middle Ages.[3] The region, home to approximately 3 million inhabitants across an area of about 22,600 square kilometers, features diverse landscapes from the fertile lowlands of South Moravia to the uplands of the Bohemian-Moravian Heights and the White Carpathians.[4] Historically, Moravia served as the heartland of the Great Moravian Empire, a West Slavic state established around 830 under Mojmír I and reaching its zenith under Svatopluk I in the late 9th century, before its dissolution by Magyar incursions circa 907.[5][6] This empire facilitated the arrival of the Byzantine missionaries Cyril and Methodius, who developed the Glagolitic script and Slavic liturgy, laying foundations for Slavic cultural and religious autonomy amid Frankish and Byzantine influences.[7] Following incorporation into the Přemyslid Bohemian realm by the 11th century, Moravia evolved as a margraviate under Habsburg rule from 1526, contributing to the industrial and agricultural prowess of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[8] In the contemporary Czech Republic, Moravia's major cities, including Brno—the nation's second-largest—and Olomouc, drive economic activity through engineering, textiles, automotive manufacturing, and viticulture, with South Moravian wines holding protected designations.[9] The region's distinct Moravian identity, reflected in dialects, folk traditions, and regionalist sentiments, persists despite post-1948 administrative fragmentation into modern NUTS regions like South Moravia and Olomouc, amid debates over historical narratives influenced by national historiographies.[10]

Etymology

Name Origins and Historical Usage

The name Moravia derives from the principal river of the region, the Morava, whose ancient hydronym appears as Marus in Latin sources and March in German, likely stemming from a Proto-Indo-European root *mor- or *mar- associated with bodies of water, swamps, or boundaries.[11] This riverine origin reflects the region's geographic centrality, as the Morava demarcates much of its eastern extent and served as a key axis for early settlement and trade routes. The Slavic form Morava itself entered usage with the arrival and consolidation of West Slavic tribes in the area from the 6th century onward, though the name predates Slavic dominance, possibly tracing to Celtic or pre-Indo-European substrates.[11] Historically, the name first emerges in written records in the early 9th century, denoting a Slavic polity rather than a strictly geographic entity. Frankish annals record the Marahenses (Moravians) in 822, describing their embassy to Louis the Pious amid conflicts with neighboring Avars and Bulgars, marking the earliest Latin attestation of the ethnonym tied to the riverine territory.[12] By the 830s, under Prince Mojmír I, Moravia designated the unified principality encompassing territories along the Morava and its tributaries, as evidenced in the Annals of St. Bertin and other Carolingian chronicles reporting Mojmír's consolidation of power and conflicts with the East Frankish Empire.[13] The epithet Great Moravia (Magna Moravia in Latin, Megale Moravia in Byzantine Greek) arose during Svatopluk I's reign (871–894), signifying imperial expansion beyond the core river valley to include Pannonia and parts of modern Slovakia, as chronicled in the Annals of Fulda.[14] Following the empire's collapse circa 906–907 due to Magyar incursions, the name endured for the surviving eastern marchlands under Bohemian overlordship. From the 11th century, it formalized as the Margraviate of Moravia (Marchia Moraviae), a semi-autonomous fief of the Přemyslid dukes of Bohemia, with boundaries roughly aligning with the Morava's watershed.[13] German-speaking Habsburg administrators rendered it Mähren from the 14th century, emphasizing the March frontier connotation amid colonization and feudal restructuring, while Czech usage retained Morava for both land and people. This dual nomenclature persisted into the 20th century, notably in the 1939–1945 Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, though post-1945 communist frameworks subordinated it to broader Czechoslovak identity until the 1993 Velvet Divorce.[15] Throughout, Moravia connoted not only hydrology but also distinct cultural and political identity vis-à-vis Bohemia, evidenced in medieval charters, coinage, and seals bearing the region's silver-red arms.[13]Geography

Physical Features and Borders

Moravia constitutes the eastern portion of the Czech Republic, historically delineated by natural and political boundaries that separate it from Bohemia to the west, the Moravian-Silesian region and Polish Silesia to the northeast, Slovakia to the east, and Austria (Lower and Upper Austria) to the south.[16][17] In contemporary administrative terms, Moravia's extent overlaps primarily with the South Moravian, Olomouc, and Zlín Regions, along with portions of the Vysočina and Moravian-Silesian Regions, though these modern divisions do not precisely align with historical demarcations preserved in ecclesiastical or cultural contexts.[18][19] The region's terrain is characterized by a mix of lowlands, plateaus, and uplands, generally flatter than adjacent Bohemia, with elevations ranging from approximately 200 meters above sea level in the southern lowlands to a maximum of 1,495 meters in the northern highlands.[20][17] Central and southern Moravia features fertile lowlands and rolling plains, particularly in areas like the Haná and Slovácko basins, which slope southward toward the Vienna Basin and support intensive agriculture due to alluvial soils deposited by river systems.[16] To the west, the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands form a transitional zone of undulating hills and plateaus averaging 500 to 800 meters, while eastern fringes include the low White Carpathians and scattered hill ranges.[21] Northern Moravia encompasses more rugged terrain, including the Hrubý Jeseník range, where the highest elevations occur near Praděd at 1,491 meters above sea level, marking the region's topographic peak and influencing local microclimates with steeper gradients and forested slopes.[20][22] Major rivers define much of the hydrology, with the Morava River serving as the principal waterway, draining nearly 28 percent of Czech territory southward to the Danube and shaping the lowland morphology through meandering channels and floodplains.[19] Tributaries such as the Dyje (Thaya) converge with the Morava near the southern border, forming extensive riparian zones, while the northward-flowing Oder (Odra) influences the northeastern periphery.[23] These fluvial systems, originating in surrounding mountains, have historically facilitated connectivity across Central Europe while contributing to sediment-rich valleys conducive to settlement and cultivation.[17]Climate and Natural Resources

Moravia experiences a temperate continental climate characterized by four distinct seasons, with cold winters averaging around -4 °C in urban areas like Brno and milder, warmer summers reaching up to 25 °C from May to September.[24] Winters often feature snow cover due to temperatures frequently dropping below freezing, while summers are moderately humid with occasional heatwaves exceeding 30 °C in the southern lowlands.[25] Precipitation is relatively even throughout the year, averaging 500-700 mm annually, though the southern Moravian wine regions benefit from a milder microclimate conducive to viticulture, with up to 96% of Czech vineyards concentrated there owing to favorable summer warmth and lower frost risk.[26] Northern and eastern highlands, such as the Jeseníky Mountains, exhibit cooler conditions with higher rainfall and more pronounced seasonal contrasts, influencing local agriculture and forestry patterns.[18] Natural resources in Moravia are dominated by fertile arable land supporting extensive agriculture, including wheat, barley, potatoes, and renowned wine production in the south, alongside vast forests covering hilly and mountainous areas that provide timber and sustain biodiversity.[27] The region holds significant mineral deposits, particularly coal in the northern Moravian-Silesian industrial belt, which has historically fueled energy and steel production but faces phase-out by the late 2020s amid environmental shifts.[28] Metallic ores like iron, silver, and gold have been extracted from the Jeseníky Mountains, supporting past metallurgical development, while south Moravia's Vienna Basin contains associated oil and natural gas reserves.[29] [30] Abundant spring water resources and river systems, including the Morava River, further contribute to hydrological assets used for irrigation, hydropower, and regional water supply.[31]History

Prehistory and Early Inhabitants

Human presence in Moravia traces back to the Lower Paleolithic period, with evidence of early hominins dating to approximately 800,000 years ago, as indicated by footprints and stone tools found in the region's karst caves and river terraces.[32] The Upper Paleolithic features prominently through sites associated with the Gravettian culture, particularly Dolní Věstonice near Brno, occupied around 29,000 to 25,000 BCE by mammoth hunters who produced some of the earliest known fired ceramics, including the Venus of Dolní Věstonice figurine, standing 111 mm tall and symbolizing fertility.[33] [34] [35] This settlement cluster, including Pavlov, yielded over 30,000 flint tools, bone artifacts, and evidence of semi-permanent dwellings with hearths, reflecting advanced hunting strategies and symbolic behavior during the Last Glacial Maximum.[36] The transition to the Neolithic occurred with the arrival of the Linearbandkeramik (LBK) culture around 5500 BCE, introducing agriculture, longhouses, and pottery with linear incisions across South Moravia's loess soils. LBK communities relied on mixed subsistence of crop cultivation (e.g., emmer wheat, barley), animal husbandry (cattle, pigs, sheep), and foraging, as evidenced by faunal remains and pollen analyses from settlements like Vedrovice.[37] Burials, such as those at Vedrovice with stable isotope data showing local diets dominated by C3 plants and terrestrial proteins, indicate stable village life until circa 4900 BCE, when the culture declined amid climatic shifts and social stresses.[38] Subsequent Chalcolithic and Bronze Age developments included the Corded Ware culture (circa 2600 BCE), marked by battle-axe burials with circular ditches in Central Moravia, and the Nitra culture (2100–1800 BCE), featuring the region's largest known burial ground with 130 graves containing urns, bronzes, and amber beads, signifying intensified metallurgy and trade networks.[39] [40] In the Iron Age, from the 4th century BCE, Celtic tribes, including groups akin to the Boii, inhabited Moravia, establishing oppida and coinage systems before displacement by Germanic Suebi confederations like the Marcomanni under Maroboduus (9 BCE–19 CE) and the Quadi, who dominated the area through Roman-era conflicts documented in Tacitus's accounts.[32] These groups practiced fortified settlements, ironworking, and amber trade until the Migration Period, setting the stage for later Avar and Slavic incursions in the 6th century CE.[41]Great Moravia Empire

Great Moravia emerged as the first major West Slavic state in Central Europe during the 9th century, with its core territories centered along the Morava River, encompassing regions now in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The state was established around 830 under Mojmir I, who united the principalities of Moravia and Nitra, initiating the Mojmirid dynasty that ruled from the 830s until its dissolution. Archaeological evidence from fortified settlements like Mikulčice, featuring multiple churches, palaces, and extensive ramparts, substantiates the existence of a centralized polity with sophisticated administrative and defensive structures.[42][43] Under Rastislav (r. 846–870), Great Moravia expanded and sought independence from Frankish influence by inviting the Byzantine missionaries Cyril and Methodius in 863 to evangelize in the Slavic vernacular, leading to the development of the Glagolitic script and [Old Church Slavonic](/page/Old Church_Slavonic) liturgy. This mission countered Latin-rite pressures from the Franks and fostered cultural autonomy, though it provoked conflicts culminating in Rastislav's betrayal and imprisonment by East Francia in 870. Svatopluk I (r. 870–894) then consolidated power, extending control over Bohemia, parts of Pannonia, and southern Poland through military campaigns and alliances, achieving peak territorial extent by allying temporarily with Franks before asserting sovereignty.[44][45][46] The empire's decline followed Svatopluk's death in 894, with his sons' succession disputes fragmenting unity; Mojmir II (r. 894–907) faced invasions by Magyars around 902–907, compounded by Bohemian defection to East Francia and internal revolts. Frankish annals record the Moravian realm's effective collapse by 907, though remnants persisted briefly under figures like Slavomir. Archaeological layers at sites such as Mikulčice show destruction and abandonment post-900, aligning with textual accounts of Magyar incursions disrupting trade and settlement networks. Great Moravia's legacy lies in pioneering Slavic statehood, literacy, and ecclesiastical traditions that influenced later Czech and Slovak polities, evidenced by enduring motifs in regional historiography and material culture.[42][43][44]Medieval Integration and Bohemian Crown

Following the collapse of Great Moravia around 907 AD, the region fragmented into smaller principalities amid invasions by Magyars and temporary Polish dominance. In 999, Polish Duke Bolesław I Chrobry annexed Moravia, incorporating it into his realm until Bohemian forces under Duke Břetislav I intervened. Břetislav I launched a campaign in 1029, defeating Polish forces and reclaiming Moravian territories, including Olomouc, thereby permanently linking Moravia to Bohemia under Přemyslid rule.[47] This conquest, solidified by 1031, marked the onset of sustained Bohemian overlordship, with Moravia thereafter treated as a subordinate province rather than an independent entity.[48] Under the Přemyslids, Moravia was divided among junior dynasts into appanage duchies—primarily Brno, Olomouc, and Znojmo—to manage succession and maintain loyalty to the Bohemian duke. These subdivisions allowed local governance while ensuring tribute and military support flowed to Prague, fostering economic ties through trade routes along the Morava River and shared Slavic cultural practices. By the mid-12th century, internecine conflicts among Moravian princes weakened autonomy, prompting centralization efforts by Bohemian rulers like Vladislav II.[48] The arrangement emphasized feudal hierarchy, with Moravian lords swearing fealty to the Bohemian sovereign, who in turn defended against external threats such as Hungarian incursions in the 11th and 12th centuries.[49] In 1182, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa intervened to unify the fragmented Moravian duchies into a single margraviate, granting the title to Conrad II of Brno and Otto III of Olomouc's lineage, while affirming its subordination to the Kingdom of Bohemia. This elevation to margraviate status provided imperial privileges, such as direct access to the emperor, but preserved Bohemian suzerainty, as margraves remained vassals of the Bohemian king.[50] Subsequent margraves, including Vladislaus Henry (r. 1197–1222), balanced local interests with crown obligations, promoting German settlement in border areas to bolster defenses and agriculture.[50] The margraviate's integration deepened during the 13th century under kings like Přemysl Otakar II, who expanded Bohemian influence across Central Europe, incorporating Moravia into broader territorial ambitions while investing in fortifications and ecclesiastical foundations. Moravia contributed troops and resources to Bohemian campaigns, such as against Hungary, and benefited from royal patronage in mining silver at Kuntice and Jihlava. This era saw cultural convergence, with Latin liturgy and Romanesque architecture proliferating, exemplified by structures like the Basilica of St. Procopius in Třebíč, begun in the early 12th century.[48] By the late Přemyslid period, Moravia's status as a crown land was entrenched, paving the way for its role in the electoral Kingdom of Bohemia after 1198.[49]Habsburg Era Developments

Following the election of Ferdinand I as Margrave of Moravia in 1527, the region integrated into the Habsburg Monarchy as a crown land alongside Bohemia and Austrian Silesia. Unlike the more resistant Bohemian estates, Moravian nobility largely accepted Habsburg hereditary rule by 1627, avoiding the immediate confiscations that followed the Bohemian defeat at the Battle of White Mountain in 1620.[51] This accommodation stemmed from strategic alliances and the desire to preserve local privileges amid religious tensions between Protestant majorities and Catholic Habsburg rulers. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) brought severe devastation to Moravia, with Swedish forces sacking Olomouc in 1642 and reducing the population by approximately one-third through combat, famine, and disease.[52] Post-war recatholicization under Ferdinand III and Leopold I enforced Catholic orthodoxy, closing Protestant churches, expelling or converting non-Catholics, and promoting Jesuit missions; by the late 17th century, Catholicism dominated, supported by Habsburg policies that tied land ownership to religious conformity.[51] Administrative centralization advanced under Leopold I, with German increasingly used in governance, though Moravia retained its Diet and governorate in Brno. The 18th century marked economic recovery and cultural efflorescence under Maria Theresa and Joseph II. Agricultural reforms modernized estates, boosting grain and wine production, while noble initiatives laid foundations for proto-industrial activities like textile manufacturing in Brno.[53] Baroque architecture proliferated, exemplified by reconstructions in Olomouc and Brno, including fountains and palaces funded by Habsburg loyalists.[54] Joseph II's 1781 Edict of Tolerance granted limited rights to Protestants and Jews, while abolishing serfdom and robot labor, easing peasant burdens and stimulating labor mobility, though many reforms faced noble resistance and partial reversal after his death in 1790.[55] These changes positioned Moravia as an agricultural exporter within the monarchy, with per capita growth accelerating by the late 18th century.[56]Nationalist Awakenings in the 19th Century

The nationalist awakenings in 19th-century Moravia emerged within the Habsburg Empire's multi-ethnic framework, where regional patriotism intertwined with the Slavic cultural revival, emphasizing preservation of Moravian distinctiveness amid German linguistic dominance and Bohemian-led Czech initiatives. Early institutional efforts focused on historical documentation and artifact collection, exemplified by the founding of the Moravian Museum in Brno on July 29, 1817, through a decree by Emperor Francis I, which aimed to catalog regional heritage and counteract cultural erosion under centralized Austrian administration.[57] This reflected broader Enlightenment influences but prioritized local estates' interests, fostering a sense of provincial identity rooted in medieval privileges rather than full ethnic separatism. By the 1830s and 1840s, Moravian scholars contributed to philological and antiquarian work, reviving interest in the Great Moravian Empire (9th century) as a symbol of Slavic precedence, though these activities lagged behind Bohemian counterparts due to stronger Germanization in urban centers like Brno and Olomouc. The revolutions of 1848 catalyzed wider dissemination of Czech-language nationalism among Moravia's Czech-speaking peasantry and bourgeoisie, previously confined to nobility and clergy. The Moravian Diet, reconvened after decades of suspension, issued key reforms including the abolition of serfdom on March 18, 1848, and prepared electoral rules for a representative assembly that convened in Brno on May 31, reflecting demands for civil liberties and administrative decentralization.[58] Czech activists, inspired by pan-Slavic gatherings like the Prague Slavic Congress, pushed for language equality in education and courts, heightening tensions with German nationalists who controlled most municipal governments and opposed bilingual concessions. However, Moravian representatives resisted Bohemian proposals for constitutional unification of Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia, petitioning Emperor Ferdinand I to maintain Moravia's status as a separate crown land to safeguard local diets and economic privileges.[59] This "Moravianism"—a loyalty to provincial estates—tempered full alignment with Prague-centered Czech irredentism, as evidenced by growing Czech-German antagonism in spring assemblies where Czech petitions garnered limited support amid German majorities.[60] Post-1848 reaction suppressed overt political agitation, but cultural organizations endured, with the private founding of Matice Moravská in 1849 to promote literature, science, and education in Czech, mirroring Bohemia’s Matice česká but adapted to regional needs.[61] By the 1860s, amid Austro-Hungarian Compromise debates, Moravian delegates in imperial diets advocated federalism, influencing figures like František Ladislav Rieger, whose Old Czech Party sought Habsburg constitutional reforms granting Czechs parity without alienating conservative landowners. These efforts solidified Moravian identity as a subset of Czech ethnicity, prioritizing pragmatic autonomy over revolutionary separatism, though they faced setbacks from Vienna's centralism and internal divisions between urban liberals and rural traditionalists.World Wars and Interwar Independence Efforts

Following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire amid the final stages of World War I, Moravia was incorporated into the newly proclaimed Republic of Czechoslovakia on October 28, 1918, alongside Bohemia, Austrian Silesia, and Slovakia, marking the end of Habsburg rule over the region.[62] This transition was facilitated by the Czechoslovak National Council, which had organized exile efforts and leveraged Allied support during the war, though Moravia itself experienced minimal direct combat compared to frontline areas.[62] In the interwar First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938), Moravia functioned as a distinct administrative unit with its own land assembly (zemský sněm), but the central Prague government maintained unitary control, prioritizing national unity over regional devolution amid ethnic tensions with German and Hungarian minorities. Moravian regionalist movements emerged, advocating for cultural preservation, economic self-governance, and limited autonomy to counter Bohemian dominance in politics and industry; groups such as the Moravian Christian Social Party emphasized Moravian identity in elections, securing representation but failing to achieve substantive federal reforms due to opposition from centralist Czech parties and the need for stability against external threats.[63] These efforts reflected pragmatic demands for administrative decentralization rather than outright secession, with Moravian deputies influencing policies on agriculture and education but yielding to national priorities, as evidenced by the 1920 constitution's rejection of full federalism.[64] The Munich Agreement of September 30, 1938, ceded the Sudetenland—home to over 3 million German speakers, including border areas of Moravia—to Nazi Germany, precipitating the republic's collapse and exposing vulnerabilities in its multi-ethnic structure. On March 15, 1939, German forces occupied the remaining Czech lands, establishing the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as a nominally autonomous entity under President Emil Hácha, though real power resided with Berlin-appointed Reichsprotektors enforcing economic exploitation and political suppression.[65] Industrial output from Moravian factories, such as Škoda Works in Brno, was redirected to the German war machine, while resistance networks formed, culminating in the May 27, 1942, assassination of Reichsprotektor Reinhard Heydrich by Czech paratroopers trained in Britain.[66] Heydrich's death triggered brutal reprisals, including the total destruction of the Moravian village of Lidice on June 10, 1942, where 173 men were executed, women and children deported, and the site razed, symbolizing Nazi terror tactics to quell dissent.[66] Moravian autonomy aspirations were extinguished under the protectorate's dual legal system, which applied German law to ethnic Germans while subjugating Czechs and Moravians through censorship, forced labor, and deportation of approximately 82,000 Jews from the protectorate to death camps. The region saw liberation in spring 1945, with eastern Moravia freed by Soviet forces in April and Prague by a combined uprising and Allied advance in May, restoring Czechoslovak sovereignty but under emergent communist influence.[65]Communist Period and Suppression

Following the communist coup d'état on February 25, 1948, which installed the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) in full control of the government, Moravia was integrated into the centralized Czechoslovak Socialist Republic as a non-autonomous territory.[67] The regime promptly pursued administrative centralization to dismantle historical regional structures perceived as potential bases for nationalist deviation or bourgeois separatism. On January 1, 1949, the Moravian-Silesian Land was abolished through a sweeping territorial reform that replaced traditional provinces (země) with 19 new regions (kraje), effectively erasing Moravia's distinct administrative existence and subordinating it to Prague's direct oversight.[68] [69] This reform, enacted by decree of the KSČ-dominated National Assembly, aimed to enforce ideological uniformity by eliminating autonomist institutions that could foster regional loyalties over proletarian internationalism.[70] Throughout the 1948–1989 period, the KSČ systematically suppressed manifestations of Moravian regionalism, branding them as reactionary remnants incompatible with the unitary socialist state. Public expressions of Moravian patriotism—such as advocacy for regional symbols, dialects in official contexts, or historical narratives emphasizing Moravian distinctiveness—were curtailed through censorship, political purges, and indoctrination campaigns that prioritized a homogenized Czech identity subsumed under Czechoslovak socialism.[71] Education and media were standardized to promote Standard Czech over Moravian dialects, while cultural institutions in cities like Brno were reoriented toward class-struggle propaganda, sidelining local traditions.[72] The regime's security apparatus, including the State Security (StB), monitored and repressed individuals or groups evoking Moravian exceptionalism, often equating it with anti-communist dissent; for instance, pre-1948 Moravian autonomy advocates were labeled nationalists and subjected to show trials or internment in labor camps like those in the Jáchymov uranium mines.[73] Economic policies further eroded regional agency, as collectivization of agriculture—completing by 1960 with over 90% of farmland under state control—and forced industrialization redirected Moravian resources to national five-year plans without regard for local priorities.[74] Northern Moravia's Ostrava-Karviná coal basin became a hub for heavy industry, employing hundreds of thousands in state-run enterprises like the Vitkovice steelworks, but profits flowed centrally, fostering resentment suppressed via party loyalty oaths and surveillance. The 1968 Prague Spring briefly revived federalization discussions, establishing the Czech Socialist Republic (encompassing Moravia) alongside Slovakia, yet this devolved limited powers that excluded substantive Moravian self-rule.[75] The Warsaw Pact invasion on August 21, 1968, and subsequent "normalization" under Gustáv Husák intensified crackdowns, purging over 300,000 KSČ members nationwide (including Moravian cadres) and reinstating strict ideological conformity that stifled any residual regionalist undercurrents until the late 1980s.[76] Despite this, clandestine cultural persistence—through folk traditions and underground samizdat—sustained latent Moravian identity, which the regime tolerated only insofar as it did not challenge KSČ hegemony.[71]Velvet Revolution and Contemporary Status