Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ivinghoe

View on Wikipedia

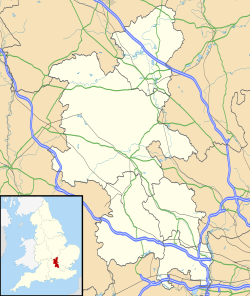

Ivinghoe is a town and civil parish in east Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders with Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire. It is 33 miles (53 kilometres) northwest of London, 4 mi (6 km) north of Tring and 6 mi (10 km) south of Leighton Buzzard, close to the village of Pitstone.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]The town name is Anglo-Saxon in origin, and means 'Ifa's hill-spur'. The same name is found in Ivington (He) and its strong form in Iveston and Ivesley (Du).[3] The term "hoh" ('projecting ridge of land, a promontory' similar to German Höhe) refers probably to Ivinghoe Beacon. Allen Mawer notes that Ivinghoe is located "at the base of a considerable spur of land jutting out from the main range of the Chilterns".[4] In the Domesday Book of 1086 it was recorded as Evinghehou.[5] Other forms: Iuingeho, Hythingho, Yvyngho (xii–xiii cent.); Ivanhoe (xvii cent.)[6]

Ivinghoe and Ivanhoe

[edit]Ivanhoe is an alternative form of Ivinghoe.[6] It is the inspiration for the title of Walter Scott's most famous novel. Ivanhoe is the feudal title of Wilfred of Ivanhoe. In the novel, Richard Coeur de Lion gives Wilfred the investiture of the Lordship of the Manor (Fief) of Ivanhoe.

Scott took the name from an old rhyme (Tring, Wing and Ivanhoe, For striking of a blow, Hampden did forego, And glad he could escape so ..”). The form "Ivanhoe" is recorded in the Hertfordshire county sessions records for 1665. Until the creation of the Ordnance Survey in the mid 19th century many place names remained uncertain and varied. They often depended on local use and how they might have been written in various documents over time. Prof. Paul Kerswill (a linguistics specialist) writes in a private letter to Dr. Marco Paret (Lord of the Manor of Ivinghoe),[7] that "it is very likely that older, rural people in the Ivinghoe area would have pronounced the name in the same way as Ivanhoe, also dropping the h. Something like 'ivanoe'. the suffix -ing is pronounced 'in' in most dialects in the English-speaking world - and has been for many centuries." Sir Walter Scott most likely knew Ivinghoe directly. He stayed at “Stocks" in Berkhamsted for a short time. Berkhamsted is 8 miles (13 kilometres) from Ivinghoe.[8]

Location

[edit]Ivinghoe is situated within the Chiltern Hills, on the edge of the Chilterns' Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[9] Ivinghoe is an important point on the Icknield Way, joining the Upper Icknield and Lower Icknield together. The Icknield Way is claimed to be the oldest road in Britain, dating back to the Celtic period, though this has been disputed.[10][11][12][13][14] Today the village is known as a starting point on The Ridgeway, a popular route for hikers and cyclists which uses part of the Icknield Way, running for 87 miles (140 kilometres) to Overton Hill in Wiltshire.

Ivinghoe Aston is a hamlet within the parish of Ivinghoe. Its name refers to a farm to the east of the town. The hamlet has four farms, several houses and a public house, The Village Swan, which was bought by local residents in 1997.[15]

A small stream called Whistle Brook flows down through the hamlet, from the Chilterns above, to join the River Ouzel at nearby Slapton.

Other hamlets close to Ivinghoe are Ford End and Great Gap.

Buildings

[edit]

The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Ivinghoe dates from 1220 but was set on fire in 1234 in an act of spite against the local Bishop. The church was rebuilt in 1241.

The town has some fine examples of Tudor architecture, particularly around the village green, with 28 buildings marked as listed or significant.[9]

Ivinghoe Beacon, near the town, is an ancient beacon, or signal point, which was used in times of crisis to send messages across the country and is now popular with walkers who just want to get exercise and see the view. It is used as a site for flying model aeroplanes. The hill is the site of an early Iron Age hill fort which, during excavations in the 1960s, was identified from bronzework finds to date back to the Bronze-Iron transition period between 800 and 700 BC. Like many other similar hill forts in the Chilterns it is thought to have been occupied for only a short period, possibly less than one generation.

Nearby is Pitstone Windmill, the oldest windmill in Britain that can be dated, which is owned by the National Trust.[16]

The population of Ivinghoe in 1841 was 740.[17]

Lords of the Manor

[edit]The manor of Ivinghoe belonged before the Norman Conquest to the demesne of the church of St Peter of Winchester, and at the time of the Domesday Survey it was still held by the bishop, being assessed for 20 hides and valued at £18. It is listed in the Domesday Book of 1086 as “Evinghehou”.

Succeeding bishops held the manor until the reign of Henry VIII. Lords included William Giffard, Henry of Blois, Godfrey de Luci, John Gervais, Nicholas of Ely, John of Pontoise, John de Stratford, Cardinal Henry Beaufort, William Waynflete, and Richard Foxe. In 1531 William Cholmeley was appointed to be bailiff of Ivinghoe, which had come into the king's hands by the forfeiture of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who was BoBishop of Winchester. It was, however, restored to the bishopric almost at once to Bishop Stephen Gardiner, and so remained until in 1551, when John Poynet, bishop, surrendered it to the King. In the following month Edward VI made a grant in fee of the manor to Sir John Mason (diplomat), kt., and Elizabeth his wife.

After the death of Edward VI and the flight of Poynet, Ivinghoe, with other episcopal manors, was regranted to the see of Winchester, but was again taken by the Crown at the accession of Elizabeth, the grant to Mason apparently holding good, passing to his son Anthony.

The Egerton Family and Ivinghoe

Anthony Mason held the manor in 1582 and in 1586 alienated the manor to Charles Glenham who sold it in 1589 to Lady Jane Cheyne, widow of Henry Lord Cheyne. In 1603 she conveyed the manor to Ralph Crewe, Thomas Chamberlayn and Richard Cartwright, trustees for the Egertons, and Sir Thomas Egerton, 1st Viscount Brackley, and Sir John Egerton, 1st Earl of Bridgewater, his son and heir, received Ivinghoe from the trustees in 1604.

Lord Ellesmere, who also bore the title of Viscount Brackley, died seised of the manor in 1617. In the same year his son was created Earl of Bridgewater and the manor descended with this title until the latter became extinct in 1829.

By the will of the seventh earl, who died in 1823, the estates were then held by his widow until her death in 1849, when they devolved upon his great-nephew John Egerton, Viscount Alford, father of the second Earl Brownlow, from whom the title and lands descended to the Barons Brownlow. The sixth Baron, notably served as a Lord-in-waiting to the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII), as Mayor of Grantham, as Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Minister of Aircraft Production Lord Beaverbrook and as Lord Lieutenant of Lincolnshire. As of 2017[update] the titles are held by his son, the seventh Baron, who succeeded in 1978. Edward John Peregrine Cust (b.1936), CStJ, seventh Baron Brownlow, is the immediate past Lord of the Manor of Ivinghoe. He married Shirlie Edith Yeomans (b.1937), daughter of John Paske Yeomans and Marguerite Watkins, on 31 December 1964. The seventh Baron Brownlow is the last of the direct Egerton line to have hold the Manor of Ivinghoe. Actual Lord of the Manor is Dr. Marco Paret that succeeded to an Egerton descendent. The Lord of the Manor has still the right to hold the customary Courts Baron and Court Leet as permitted by Administration of Justice Act 1977.[18]

On Film

[edit]Scenes for feature films, such as Quatermass 2, Batman Begins, Maleficent, The Dirty Dozen, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (film), Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker as well as the BBC America production Killing Eve, have been shot at Ivinghoe Beacon.[19] Director Raymond Austin filmed the 1960s-1970's TV shows The Avengers, The New Avengers and The Saint in and around the village,[20] which once also served as a set for the children's TV series ChuckleVision. The opening scene in Wicked, set in Munchkinland, was also shot there.[21]

Schools

[edit]Brookmead School is a mixed, foundation primary school in Ivinghoe. It takes children from the ages of four to eleven. The school has about 300 pupils.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Ivinghoe Parish (E04001498)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Parliamentary 2024 Constituency Map for Aylesbury". streetguide.co.uk. July 2024. Retrieved 13 September 2025.

- ^ "Ivinghoe :: Survey of English Place-Names". epns.nottingham.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Mawer, A.; Stenton, F.M. (1925). The Place-Names of Buckinghamshire (English Place-Name Society, vol. II). Cambrídge: At the University Press. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ "Ivinghoe | Domesday Book".

- ^ a b "Parishes: Ivinghoe | British History Online".

- ^ "IVANHOE/IVINGHOE - BUCKINGAMSHIRE". www.ivanhoemanor.com.

- ^ "Some Notable Berkhampsted Women" (PDF). Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Aylesbury Vale District Council Ivinghoe Conservation Area Review, 2015" (PDF). Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ S. Harrison, "The Icknield Way: some queries", The Archaeological Journal, 160, 1–22, 2003.

- ^ K. Matthews, Circular Walk (Wilbury Hill, Ickleford, Cadwell, Wilbury Hill) Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ R. Bradley, Solent Thames Research Assessment – the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2008.

- ^ W.G. Clarke In Breckland Wilds, Heffer, Cambridge; 2nd edition, 1937; p.67.

- ^ Rhiannon, The Icknield Way: Miscellaneous, 2008.

- ^ "The Village Swan website". Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "National Trust: Pitstone Windmill". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.III, London, (1847), Charles Knight, p.898

- ^ "Other Notices | the Gazette".

- ^ "Leighton Buzzard Observer: Road closure today as BBC America drama filmed around Ivinghoe Beacon and residents warned about gun shots". Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Avengerland TV location guide". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Where Was Wicked Filmed? From Munchkinland to Shiz University". NBC Insider Official Site. 27 November 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "Brookmead School website". Retrieved 13 September 2025.

External links

[edit]Ivinghoe

View on GrokipediaGeography and environment

Location and boundaries

Ivinghoe is a village and civil parish situated in the eastern part of Buckinghamshire, England, approximately 33 miles northwest of London and near the county's borders with Hertfordshire to the southeast and Bedfordshire to the northeast.[8][9][10] The civil parish boundaries encompass the central village of Ivinghoe along with several hamlets and dispersed settlements, including Ivinghoe Aston, Ringshall, Horton Wharf, Ford End, and Great Gap, forming a "strip parish" characteristic of the Icknield Belt region where the flat Vale of Aylesbury transitions to the Chiltern Hills.[11][1][2] Ivinghoe maintains close geographical relations with nearby towns, such as Tring in Hertfordshire, located about three miles to the southwest, and Pitstone in Bedfordshire, which lies adjacent to the parish's northern edge.[10][12] The parish falls within the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, positioned on its northwestern fringe.[1][13]Landscape features

Ivinghoe is situated within the Chiltern Hills, a range of chalk downlands characterized by rolling hills, dry valleys, and extensive beech woodlands that define the area's natural topography. The landscape features gently rounded hills with steeper escarpments, supporting a mix of open grasslands and scrub on slopes, transitioning to pastoral and arable fields on lower ground. This undulating terrain is a key component of the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, where beech-dominated woodlands cloak many hillsides, contributing to the region's distinctive wooded character.[14][1] The most prominent feature is Ivinghoe Beacon, the highest point in the vicinity at 757 feet (231 meters) above sea level, forming a dramatic spur on the Chiltern scarp. From its summit, panoramic views extend over the flat expanse of the Vale of Aylesbury to the northwest, contrasting the elevated chalk ridges with the surrounding lowlands. This vantage point highlights the escarpment's role as a natural boundary, with the beacon's exposed position offering unobstructed sights into Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire.[15][16] Geologically, the area is underlain by Cretaceous chalk bedrock of the Chalk Group, primarily Middle Chalk formations including the distinctive Chalk Rock layer, deposited in shallow seas around 100 million years ago. This porous bedrock results in thin, calcareous rendzina soils that are free-draining, promoting the growth of chalk grassland flora while limiting water retention and influencing local hydrology through rapid infiltration and occasional springs at the scarp base. The chalk's durability shapes the downland morphology, resisting erosion to form prominent ridges and coombes.[16][17] Environmental protections underscore the landscape's ecological value, with the Ivinghoe Hills designated as a 212-hectare Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) by Natural England, encompassing botanically rich chalk downlands, semi-natural woodlands, and scrub habitats around the beacon and adjacent hills. This SSSI supports diverse calcareous grasslands and rare plant species adapted to the chalk substrate, safeguarding the area's biodiversity amid the broader Chilterns ecosystem.[18][19]History

Etymology

The name Ivinghoe originates from Old English, deriving from Ifan hōh, meaning "the hill-spur of Ifa's people," where Ifa is a personal name and hōh denotes a projecting ridge or heel of land, likely referring to the local topography including the spur at Ivinghoe Beacon.[1] This etymology is detailed in the standard scholarly work on Buckinghamshire place names.[1] The place name was first recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Evinghehou, listed among the holdings of the Bishop of Winchester in Buckinghamshire, assessed at 20 hides with a value of £18.[2] Subsequent medieval records show variations such as Iuingeho and Yvyngho in the 12th and 13th centuries, reflecting phonetic shifts in Middle English.[2] By the 17th century, the name appears as Ivanhoe in some documents, capturing a local pronunciation that softened the 'g' sound.[2] This form inspired Sir Walter Scott's choice of title for his 1819 novel Ivanhoe, as he noted in his 1830 introduction that the name was suggested by an old English rhyme alluding to forfeited manors including "Ivinghoe," which he adapted for its "ancient English sound."[20] The novel's popularity has led to unrelated modern uses of "Ivanhoe" as a place name in locations such as Australia and the United States, distinct from the Buckinghamshire village's Anglo-Saxon origins.[2]Prehistory to medieval period

Archaeological evidence indicates prehistoric occupation in the vicinity of Ivinghoe, with Palaeolithic flint tools and hand axes discovered in the broader Chilterns region, suggesting early human activity dating back to between 125,000 and 70,000 BC. More substantial settlement is attested during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, exemplified by the hillfort at Ivinghoe Beacon, a prominent site on the Chiltern escarpment established around the 8th to 7th centuries BC. This enclosure, surveyed by English Heritage in 2000, features defensive earthworks on a natural ridge and is associated with round barrows, reflecting strategic use for defense and settlement in a landscape of prehistoric trackways.[21][22] During the Roman period, Ivinghoe's location near the Icknield Way—an ancient trackway originating in prehistoric times and utilized as a major trade route—facilitated connectivity across southern England from Wiltshire to Norfolk.[1] Excavations at nearby Aston Clinton, adjacent to Ivinghoe, have uncovered evidence of Roman settlements along this corridor, including structures and artifacts indicative of agricultural and commercial activity from the 1st to 4th centuries AD, though no confirmed villa has been identified directly within Ivinghoe itself.[23] The Domesday Book of 1086 records Ivinghoe as a significant holding of 20 hides under the bishopric of Winchester (Church of St. Peter), with land sufficient for 25 ploughs, including meadows and extensive woodland supporting 600 pigs.[1] Valued at £18 annually by this time—up from £10 at acquisition and £15 in 1066—the manor supported 38 households, comprising villagers, smallholders, and slaves, underscoring its economic importance in the post-Conquest landscape.[24] Medieval development centered on the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, founded around 1220 as part of the Winchester estate. In 1234, the church and village suffered destruction by fire at the hands of rebel leader Richard Siward, who targeted properties linked to the bishop in an act of defiance against royal authority.[25] Rebuilt by 1241, the structure incorporated early 13th-century elements such as the chancel, transepts, and nave arcades, with later 14th-century additions to the tower, establishing it as a cruciform parish church emblematic of medieval ecclesiastical influence.[1]Modern history

The manor of Ivinghoe, long held by the Bishops of Winchester since before the Norman Conquest, was surrendered to the Crown in 1551 amid the broader Dissolution of the Monasteries initiated under Henry VIII. Although the process began in the 1530s with the suppression of smaller religious houses, the bishopric's temporalities were affected later; Bishop John Poynet formally relinquished the estate during the reign of Edward VI, after which it was granted to Sir John Mason and his wife Elizabeth. This transfer marked the shift from ecclesiastical to secular lordship, with subsequent owners including the Earls of Bridgewater by the 17th century, fundamentally altering local land management from church oversight to private aristocratic control.[2] Enclosure profoundly reshaped Ivinghoe's agrarian landscape in the 18th and 19th centuries, converting open fields and common lands into consolidated private holdings. An Act of Parliament in 1821 authorized the enclosure of Ivinghoe parish lands, with the award finalized in 1825 under the leadership of the Ashridge Estate, allotting approximately 19 acres in the hamlet of Aston in lieu of former commons like the Poor Close. This process, following earlier irregular enclosures common in Buckinghamshire, eliminated communal grazing and strip farming, enabling more efficient crop rotations and hedgerow boundaries but displacing smallholders and intensifying reliance on wage labor. Farming shifted toward specialized arable production of wheat, barley, and oats, boosting productivity during the Napoleonic Wars but contributing to rural depopulation during the later agricultural depression.[2][1] The 19th century saw significant population growth in Ivinghoe, driven by agricultural expansion and ancillary industries, rising from 1,215 in 1801 to 2,024 by 1851 before declining to 1,077 in 1901 amid economic pressures. Agriculture employed about 40% of families in 1831, but straw plaiting emerged as a vital cottage industry, particularly for women and children; the 1851 census recorded 107 males and 276 females engaged in it, providing supplementary income to offset low farm wages. This trade peaked mid-century but waned by the 1870s due to cheap foreign imports, exacerbating poverty and leading to widespread Poor Law reliance, with parish records noting relief for up to 200 individuals through a levied poor rate and the former workhouse at the Town Hall, which was rebuilt around 1840 after the 1834 reforms rendered local institutions obsolete.[1][26][27] In the 20th century, Ivinghoe experienced the impacts of World War II as a reception area for evacuees fleeing urban air raids, with children from London and other cities billeted in local homes to escape the Blitz, though the village itself faced only minor disruptions from occasional flyovers and distant bombings common in rural Buckinghamshire. Post-war efforts focused on preserving Ivinghoe's rural character, bolstered by the designation of the surrounding Chilterns as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1965, which restricted development and protected the landscape from urbanization; the Ashridge Estate's breakup in the 1920s had already fragmented large holdings, but conservation measures ensured controlled infilling and maintenance of historic field patterns.[28][29][7]Demographics

Population trends

The population of Ivinghoe parish has fluctuated significantly over the past two centuries, reflecting broader rural economic shifts in Buckinghamshire. In the early 19th century, the parish experienced rapid growth driven by agricultural expansion and local industry, rising from 1,215 residents in 1801 to a peak of 2,024 in 1851.[1] This mid-19th-century high was followed by a gradual decline to 1,077 by 1901, attributed to agricultural depression and out-migration to urban centers.[1]| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1801 | 1,215 |

| 1811 | 1,361 |

| 1821 | 1,665 |

| 1831 | 1,648 |

| 1841 | 1,843 |

| 1851 | 2,024 |

| 1861 | 1,849 |

| 1871 | 1,722 |

| 1881 | 1,380 |

| 1891 | 1,270 |

| 1901 | 1,077 |