Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Green Knight

View on Wikipedia

The Green Knight (Welsh: Marchog Gwyrdd, Cornish: Marghek Gwyrdh, Breton: Marc'heg Gwer) is a heroic character of the Matter of Britain, originating in the 14th-century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the related medieval work The Greene Knight. His true name is revealed to be Bertilak de Hautdesert (spelled in some translations as "Bercilak" or "Bernlak") in Sir Gawain, while The Greene Knight names him "Bredbeddle".[1]: 314 The Green Knight later features as one of Arthur's greatest champions in the fragmentary ballad King Arthur and King Cornwall, again with the name "Bredbeddle".[2]: 427

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Bertilak is transformed into the Green Knight by Morgan le Fay, a traditional adversary of King Arthur of around half-giant size, to test his court. However, in The Greene Knight, he is transformed by a different woman for the same purpose. In both stories, he sends his wife to seduce Gawain as a further test. The King Arthur and King Cornwall ballad portrays him as an exorcist and one of the most powerful knights of Arthur's court. His wider role in Arthurian literature includes being a judge and tester of knights, and as such, the other characters consider him as friendly but terrifying and somewhat mysterious.[3]

In Sir Gawain, the Green Knight is so called because his skin and clothes are green. The meaning of his greenness has puzzled scholars.[4] Some identify him as the Green Man, a vegetation being of medieval art;[3] others as a recollection of a figure from Celtic mythology;[5] a Christian "pagan" symbol – the personified Devil.[3] The medievalist C. S. Lewis said the character was "as vivid and concrete as any image in literature."[3] Scholar J. A. Burrow called him the "most difficult character" to interpret.[3]

Historical context

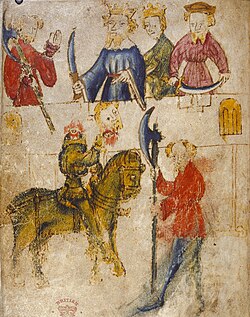

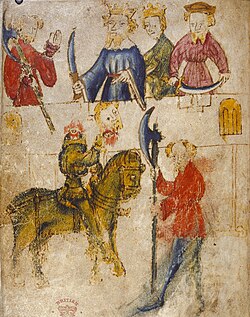

[edit]The earliest appearance of the Green Knight is in the late 14th-century alliterative poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which survives in only one manuscript along with other poems by the same author, the so-called Gawain Poet.[6] This poet was a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer, writer of The Canterbury Tales, although the two wrote in different parts of England. The later poem, The Greene Knight, is a late medieval rhyming romance that likely predates its only surviving copy: the 17th-century Percy Folio.[7] The other work featuring the Green Knight, the later ballad "King Arthur and King Cornwall", also survives only in the Percy Folio manuscript. Its date of composition is uncertain, as it may be a version of an earlier story, or possibly a product of the 17th century.[8]

Role in Arthurian literature

[edit]In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the Green Knight appears before Arthur's court during a Christmas feast, holding a bough of holly in one hand and a battle axe in the other. Despite disclaim of war, the knight issues a challenge: he will allow one man to strike him once with his axe, with the condition that he return the blow the next year. At first, Arthur accepts the challenge, but Gawain takes his place and decapitates the Green Knight, who retrieves his head, reattaches it and tells Gawain to meet him at the Green Chapel at the stipulated time.[9]

No, I seek no battle, I assure you truly:

Those about me in this hall are but beardless children.

If I were locked in my armour on a great horse,

No one here could match me with their feeble powers.

Therefore, I ask of the court a Christmas game...

The Knight features next as Bertilak de Hautedesert, lord of a large castle, Gawain's host before his arrival at the Green Chapel. At Bertilak's castle, Gawain is submitted to tests of his loyalty and chastity, wherein Bertilak sends his wife to seduce Gawain and arranges that each time Bertilak gains prey in hunting, or Gawain any gift in the castle, each shall exchange his gain for the other's. At New Year's Day, Gawain departs to the Green Chapel, and bends to receive his blow, only to have the Green Knight feint two blows, then barely nick him on the third. He then reveals that he is Bertilak, and that Morgan le Fay had given him the double identity to test Gawain and Arthur.[9]

The Greene Knight tells the same story as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, with a few differences. Notably, the knight, here named "Bredbeddle", is only wearing green, not green-skinned himself. The poem also states the knight has been asked by his wife's mother (not Morgan in this version) to trick Gawain. He agrees because he knows his wife is secretly in love with Gawain, and hopes to deceive both. Gawain falters in accepting a girdle from her, and the Green Knight's purpose is fulfilled in a small sense. In the end, he acknowledges Gawain's ability and asks to accompany him to Arthur's court.[1]

In King Arthur and King Cornwall, the Green Knight again features as Bredbeddle, and is depicted as one of Arthur's knights. He offers to help Arthur fight a mysterious sprite (controlled by the magician, King Cornwall) which has entered his chamber. When physical attacks fail, Bredbeddle uses a sacred text to subdue it. The Green Knight eventually gains so much control over the sprite through this text that he convinces it to take a sword and strike off its master's head.[2]

Etymologies

[edit]The name "Bertilak" may derive from bachlach, a Celtic word meaning "churl" (i.e. rogueish, unmannerly), or from "bresalak", meaning "contentious". The Old French word bertolais is a form of "Bertilak" in the Arthurian tale Merlin from the Lancelot-Grail cycle.[3][11] Notably, the 'Bert-' prefix means 'bright', and the '-lak' can mean either 'lake' or "play, sport, fun, etc". "Hautdesert" probably comes from a mix of both Old French and Celtic words meaning "High Wasteland" or "High Hermitage". It may also have an association with desirete meaning "disinherited" (i.e. from the Round Table).[3]

Similar or derivative characters

[edit]Green Knights in other stories

[edit]

Characters similar to the Green Knight appear in several other works. In Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, for example, Gawain's brother Gareth defeats four brothers in different coloured armour, including a "Grene Knyght" named Sir Partolope.[12] The three who survive the encounter eventually join the Round Table and appear several further times in the text. The stories of Saladin feature a certain "Green Knight"; a Spanish warrior (maybe from Castile, according to an Arab source) in a shield vert and a helmet adorned with stag horns. Saladin tries to make him part of his personal guard.[13] Similarly, a "Chevalier Vert" appears in the Chronicle of Ernoul during the recollection of events following the capture of Jerusalem in 1187; here, he is identified as a Spanish knight who earned this nickname from the Muslims due to his eccentric apparel.[14]

Some researchers have considered an association with Islamic tales.[15] The figure of Al-Khidr (Arabic: الخضر) in the Qur'an is called the "Green Man" as the only man to have drunk the water of life, which in some versions of the story turns him green.[15] He tests Moses three times by doing seemingly evil acts, which are eventually revealed to be noble deeds to prevent greater evils or reveal great goods. Both the Arthurian Green Knight and Al-Khidr serve as teachers to holy men (Gawain/Moses), who thrice tested their faith and obedience. It has been suggested that the character of the Green Knight may be a literary descendant of Al-Khidr, brought to Europe with the Crusaders and blended with Celtic and Arthurian imagery.[16]

Characters fulfilling similar roles

[edit]The beheading game appears in a number of tales, the earliest being the Middle Irish tale Bricriu's Feast. The challenger in this story is named "Fear", a bachlach (churl), and is identified as Cú Roí (a superhuman king of Munster in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology) in disguise. He challenges three warriors to his game, only to have them run from the return blow, until the hero Cú Chulainn accepts the challenge. With Cú Chulainn under his axe, this antagonist also feints three blows before letting the hero go. In the Irish version, the cloak of the churl is described as "glas", which means green.[17] In the Life of Caradoc, a Middle French narrative embedded in the anonymous First Continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail, another similar challenge is issued. In this story, a notable difference is that Caradoc's challenger is his father in disguise, come to test his honour. The French romances La Mule sans frein and Hunbaut and the Middle High German epic poem Diu Crone feature Gawain in beheading game situations. Hunbaut furnishes an interesting twist: Gawain cuts off the man's head, and then pulls off his magic cloak before he can replace it, causing his death.[18] A similar story, this time attributed to Lancelot, appears in the 13th century French work Perlesvaus.[19]

The 15th-century The Turke and Gowin begins with a Turk entering Arthur's court and asking, "Is there any will, as a brother, To give a buffett and take another?"[20]: ll. 16–17 Gawain accepts the challenge, and is then forced to follow the Turk until he decides to return the blow. Through the many adventures they have together, the Turk, out of respect, asks the knight to cut off the Turk's head, which Gawain does. The Turk, surviving, then praises Gawain and showers him with gifts. The Carle of Carlisle contains a scene in which the Carl, a lord, orders Gawain to strike off his head.[21] Gawain obliges, the Carl rises and, having been freed from a magic spell, no return blow is demanded or given.[18] Among all these stories, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is the only one with a completely green character,[7]: 310–311 and the only one tying Morgan le Fay to his transformation.[18]

Several stories also feature knights struggling to stave off the advances of voluptuous women, including Yder, the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, Hunbaut, and The Knight of the Sword. The Green Knight parallel in these stories is a King testing a knight as to whether or not he will remain chaste in extreme circumstances. The woman he sends is sometimes his wife (as in Yder), if he knows that she is unfaithful and will tempt other men; in The Knight of the Sword the king sends his beautiful daughter. All characters playing the Green Knight's role kill unfaithful knights who fail their tests.[18] Pwyll, in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, faces a similar chastity test.

Significance of the colour green

[edit]

In English folklore and literature, green has traditionally been used to symbolise nature and its embodied attributes, namely those of fertility and rebirth. Critics have claimed that the Green Knight's role emphasises the environment outside of human habitation.[23]: 37 With his alternate identity as Bertilak, the Green Knight can also be seen as a compromise between both humanity and the environment as opposed to Gawain's representation of human civilisation.[23]: 39 Often, it is used to embody the supernatural or spiritual other world. In British folklore, the devil was sometimes considered to be green which may or may not play into the concept of the Green Man/ Wild Man dichotomy of the Green Knight.[24] Stories of the medieval period also portray the colour as representing love and the amorous in life,[25] and the base, natural desires of man.[26] Green is also known to have signified witchcraft, devilry and evil for its association with the fairies and spirits of early English folklore and for its association with decay and toxicity.[27] The colour, when combined with gold, is sometimes seen as representing the fading of youth.[28] In the Celtic tradition, green was avoided in clothing for its superstitious association with misfortune and death. Green in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is ambiguous as it could have a variety of meanings: signifying a transformation from good to evil and back again, or displaying both the spoiling and regenerative connotations of the colour.[3][22]

Interpretations

[edit]Of the many characters similar to him, the Green Knight of Sir Gawain is the first to be green.[24] Because of his strange colour, some scholars believe him to be a manifestation of the Green Man figure of medieval art,[3] or as a representation of both the vitality and fearful unpredictability of nature. That he carries a green holly branch, and the comparison of his beard to a bush, has guided many scholars to this interpretation. The gold entwined in the cloth wrapped around his axe, combined with the green, gives him both a wild and an aristocratic air.[26] Others consider him as being an incarnation of the Devil.[3] In one interpretation, it is thought that the Green Knight, as the "Lord of Hades", has come to challenge the noble knights of King Arthur's court. Sir Gawain, the bravest of the knights, therefore proves himself equal to Hercules in challenging the Knight, tying the story to ancient Greek mythology.[27] Scholars like Curely claim the descriptive features of the Green Knight suggest a servitude to Satan such as the beaver-hued beard alluding to the allegorical significance of beavers for the Christian audience of the time who believed that they renounced the world and paid "tribute to the devil for spiritual freedom."[29] Another possible interpretation of the Green Knight views him as combining elements from the Greek Hades and the Christian Messiah, at once representing both good and evil and life and death as self-proliferating cycles. This interpretation embraces the positive and negative attributes of the colour green and relates to the enigmatic motif of the poem.[3] The description of the Green Knight upon his entrance to Arthur's Court as "from neck to loin… strong and thickly made" is considered by some scholars as homoerotic.[30]

C.S. Lewis declared the Green Knight "as vivid and concrete as any image in literature" and further described him as:

a living coincidentia oppositorum; half giant, yet wholly a "lovely" knight"; as full of demoniac energy as old Karamazov, yet in his own house, as jolly as a Dickensian Christmas host; now exhibiting a ferocity so gleeful that it is almost genial, and now a geniality so outrageous that it borders on the ferocious; half boy or buffoon in his shouts and laughter and jumpings; yet at the end judging Gawain with the tranquil superiority of an angelic being [31]

The Green Knight could also be interpreted as a blend of two traditional figures in romance and medieval narratives, namely, "the literary green man" and the "literary wild man."[32] "The literary green man" signifies "youth, natural vitality, and love," whereas the "literary wild man" represents the "hostility to knighthood," "the demonic" and "death." The Knight's green skin connects the green of the costume to the green of the hair and beard, thus connecting the green man's pleasant manners and significance into the wild man's grotesque qualities.[32]

Jack in the Green

[edit]The Green Knight is also compared to the English holiday figure Jack in the Green. Jack is part of a May Day holiday tradition in some parts of England, but his connection to the Knight is found mainly in the Derbyshire tradition of Castleton Garland. In this tradition, a kind of Jack in the green known as the Garland King is led through the town on a horse, wearing a bell-shaped garland of flowers that covers his entire upper body, and followed by young girls dressed in white, who dance at various points along the route (formerly the town's bellringers, who still make the garland, also performed this role). On the top of the King's garland is the "queen", a posy of bright flowers. The King is also accompanied by his elegantly dressed female consort (nowadays, confusingly, also known as the Queen); played by a woman during recent times, until 1956 "the Woman" was always a man in woman's clothing. At the end of the ceremony, the queen posy is taken off the garland, to be placed on the town's war memorial. The Garland King then rides to the church tower where the garland is hauled up the side of the tower and impaled upon a pinnacle.[33] Due to the nature imagery associated with the Green Knight, the ceremony has been interpreted as possibly deriving from his famous beheading in the Gawain poem. In this case, the posy's removal would symbolise the loss of the knight's head.[34]

Green Chapel

[edit]

In the poem Gawain, when the Knight is beheaded, he tells Gawain to meet him at the Green Chapel, saying that all nearby know where it is. Indeed, the guide which is to bring Gawain there from Bertilak's castle grows very fearful as they near it and begs Gawain to turn back. The final meeting at the Green Chapel has caused many scholars to draw religious connections, with the Knight fulfilling a priestly role with Gawain as a penitent. The Green Knight ultimately, in this interpretation, judges Gawain to be a worthy knight, and lets him live, playing a priest, God, and judge all at once.

The chapel is considered by Gawain as an evil place: foreboding, "the most accursed church", "the place for the Devil to recite matins"; but when the mysterious Knight allows Gawain to live, Gawain immediately assumes the role of penitent to a priest or judge, as in a genuine church. The Green Chapel may also be related to tales of fairy hills or knolls of earlier Celtic literature. Some scholars have wondered whether "Hautdesert" refers to the Green Chapel, as it means "High Hermitage"; but such a connection is doubted by most scholars.[3] As to the location of the chapel, in the Greene Knight poem, Sir Bredbeddle's living place is described as "the castle of hutton", causing some scholars to suggest a connection with Hutton Manor House in Somerset.[35] Gawain's journey leads him directly into the centre of the Pearl Poet's dialect region, where the candidates for the locations of the Castle at Hautdesert and the Green Chapel stand. Hautdesert is thought to be in the area of Swythamley in northwest Midland, as it is in the writer's dialect area, and matches the land features described in the poem.[36] The Green Chapel is thought to be in either Lud's Church or Wetton Mill, as these areas closely match the descriptions given by the author.[37] Ralph Elliott for example located the chapel the knight searches for near ("two myle henne" v1078) the old manor house at Swythamley Park at the bottom of a valley ("bothm of the brem valay" v2145) on a hillside ("loke a littel on the launde, on thi lyfte honde" v2147) in a large fissure ("an olde caue,/or a creuisse of an olde cragge" v2182–83).[38]

Popular culture

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding missing information. (September 2024) |

Marvel Comics has a version of the Green Knight. While his history with Gawain remains intact, this version is depicted as having been merged with the Green Man, an aspect of Gaea.[39]

The film The Green Knight depicted the titular character (performed by Ralph Ineson) as a wood-skinned character.[40] His history in King Arthur's court and being beheaded by Gawain remains intact. Unlike the poem, there is no connection between the Green Knight and Bertilak de Hautdesert.

In the video game Guild Wars 2, the Green Knight features as an optional plot point for players who play Sylvari characters. Sylvari names are also often Welsh in origin.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b anonymous. "The Greene Knight". In Hahn (1995), pp. 313–328.

- ^ a b anonymous. "King Arthur and King Cornwall". In Hahn (1995), pp. 422–432.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Besserman, Lawrence. "The Idea of the Green Knight." ELH, Vol. 53, No. 2. (Summer, 1986), pp. 219–239. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Mann, Jill (2009). "Courtly Aesthetics and Courtly Ethics in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 31 (1): 231–265. doi:10.1353/sac.2009.a380147. ISSN 1949-0755. S2CID 191181088.

The combination of his greenness with the most sophisticated luxury of courtly dress turns him into an enigmatic spectacle, one whose appearance is scrutinized in exhaustive detail over three long stanzas, as the courtiers (and the reader) try to decipher its meaning. He is at once totally open to inspection and totally opaque.

- ^ Gentile, John S. (2014). "Shape-Shifter in the Green: Performing Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Storytelling, Self, Society. 10 (2): 220–243. doi:10.13110/storselfsoci.10.2.0220. ISSN 1932-0280.

- ^ Scattergood, Vincent J. "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". In Lacy, Norris J. (Ed.), The New Arthurian Encyclopedia, p. 419–421. New York: Garland. (1991). ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.

- ^ a b Hahn, Thomas. "Introduction to "The Greene Knight"". In Hahn (1995), pp. 309–312.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas. "Introduction to "King Arthur and King Cornwall"". In Hahn (1995), pp. 419–421.

- ^ a b Wilhelm, James J. “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.” The Romance of Arthur. Ed. Wilhelm, James J. New York: Garland Publishing, 1994. 399 – 465.

- ^ "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Medieval Period. Vol. 1. ed. Joseph Black, et al. Toronto: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-609-X Intro pg. 235

- ^ Kitson, P. R. (1998). "The Name of the Green Knight". Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. 99 (1): 39–52.

- ^ Malory, Thomas; Vinaver, Eugène. Malory: Complete Works. p. 185. Oxford University Press. (1971). ISBN 978-0-19-281217-9.

- ^ Richard, Jean. "An Account of the Battle of Hattin Referring to the Frankish Mercenaries in Oriental Moslem States" Speculum 27.2 (1952) pp. 168–177.

- ^ See the "Chronique d’Ernoul et de Bernard le Trésorier", edited by L. de Mas Latrie, Paris 1871, p. 237.

- ^ a b Ng, Su Fang; Hodges, Kenneth (2010). "Saint George, Islam, and Regional Audiences in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight" (PDF). Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 32: 257–294. doi:10.1353/sac.2010.a402782. S2CID 161611641.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Lasater, Alice E. Spain to England: A Comparative Study of Arabic, European, and English Literature of the Middle Ages. University Press of Mississippi. (1974). ISBN 0-87805-056-6.

- ^ Buchanan, Alice (1932). "The Irish Framework of Gawain and the Green Knight". PMLA. 47 (2): 315–338. doi:10.2307/457878. JSTOR 457878. S2CID 163424643.

- ^ a b c d Brewer, Elisabeth. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: sources and analogues. 2nd Ed. Boydell Press. (November 1992) ISBN 0-85991-359-7

- ^ Nitze, William A. (1936). "Is the Green Knight Story a Vegetation Myth?". Modern Philology. 33 (4): 351–366. doi:10.1086/388211. JSTOR 434285.

the one version of the Green Knight story which stands apart from the other seven versions, in that in place of one challenger who loses his head—with the chance of recovering it—there is a succession of kinsmen who are beheaded in turn, doubtless at yearly intervals. This version, which has remained a crux to most investigators, is found in the Perlesvaus (P), where the tale is connected with the wasteland motif associated with the Grail.

- ^ anonymous. "The Turke and Sir Gawain". In Hahn (1995), pp. 340–351.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas. "Introduction to "The Carle of Carlisle"". In Hahn (1995), pp. 373–374.

- ^ a b Robertson, D. W. Jr. "Why the Devil Wears Green." Modern Language Notes (November 1954) 69.7 pgs. 470–472

- ^ a b George, Michael W (2010). "Gawain's Struggle with Ecology: Attitudes toward the Natural World in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". The Journal of Ecocriticism. 2 (2).

- ^ a b Krappe, A.H (April 1938). "Who Was the Green Knight?". Speculum. 13 (2): 206–215. doi:10.2307/2848404. JSTOR 2848404.

- ^ Chamberlin, Vernon A. "Symbolic Green: A Time-Honored Characterizing Device in Spanish Literature." Hispania Vol. 51, No. 1 (Mar. 1968), pp. 29–37

- ^ a b Goldhurst, William. "The Green and the Gold: The Major Theme of Gawain and the Green Knight." College English, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Nov. 1958), pp. 61–65

- ^ a b Williams, Margaret. The Pearl Poet, His Complete Works. Random House, 1967.

- ^ Lewis, John S. "Gawain and the Green Knight." College English. Vol. 21, No. 1 (Oct. 1959), pp. 50–51

- ^ Curley, Michael J. "A Note of Bertilak's Beard." Modern Philology, vol. 73, no.1, 1975, pp.70

- ^ Zeikowitz, Richard E. "Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes" College English Special Issue: Lesbian and Gay Studies/Queer Pedagogies. 65.1 (2002) 67–80.

- ^ "The Anthropological Approach," in English and Medieval Studies Presented to J.R.R. Tolkien on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday, ed. Norman Davis and C.L. Wrenn (London: Allen and Unwin, 1962), 219–30; reprinted in Critical Studies of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, ed. Donald R. Howard and Christian Zacher (Notre Dame, Ind. and London: Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1968), 63.

- ^ a b Larry D. Benson, Art and Tradition in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (New Brunswick: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1965), 56–95

- ^ Hole, Christina. "A Dictionary of British Folk Customs." Paladin Books/Granada Publishing (1978) 114–115

- ^ Rix, Michael M. "A Re-Examination of the Castleton Garlanding." Folklore (June 1953) 64.2 pgs. 342–344

- ^ Wilson, Edward (1979). "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the Stanley Family of Stanley, Storeton, and Hooton". The Review of English Studies. 30 (119). Oxford University Press: 314. ISSN 0034-6551. JSTOR 514324.

- ^ Twomey, Michael. "Hautdesert". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Twomey, Michael. "The Green Chapel". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Elliott, R. W. V. (2010). "Searching for the Green Chapel". In Lloyd Jones, J. K. (ed.). Chaucer's Landscapes and Other Essays. Melbourne: Aust. Scholarly Publishing. pp. 293–303.

- ^ Knights of Pendragon #1-12

- ^ N'Duka, Amanda (15 March 2019). "'The Green Knight': Barry Keoghan & Ralph Ineson Joins A24's Fantasy Epic". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Hahn, Thomas, ed. (1995). Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. The Middle English Texts Series. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Also known as the TEAMS Edition.