Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

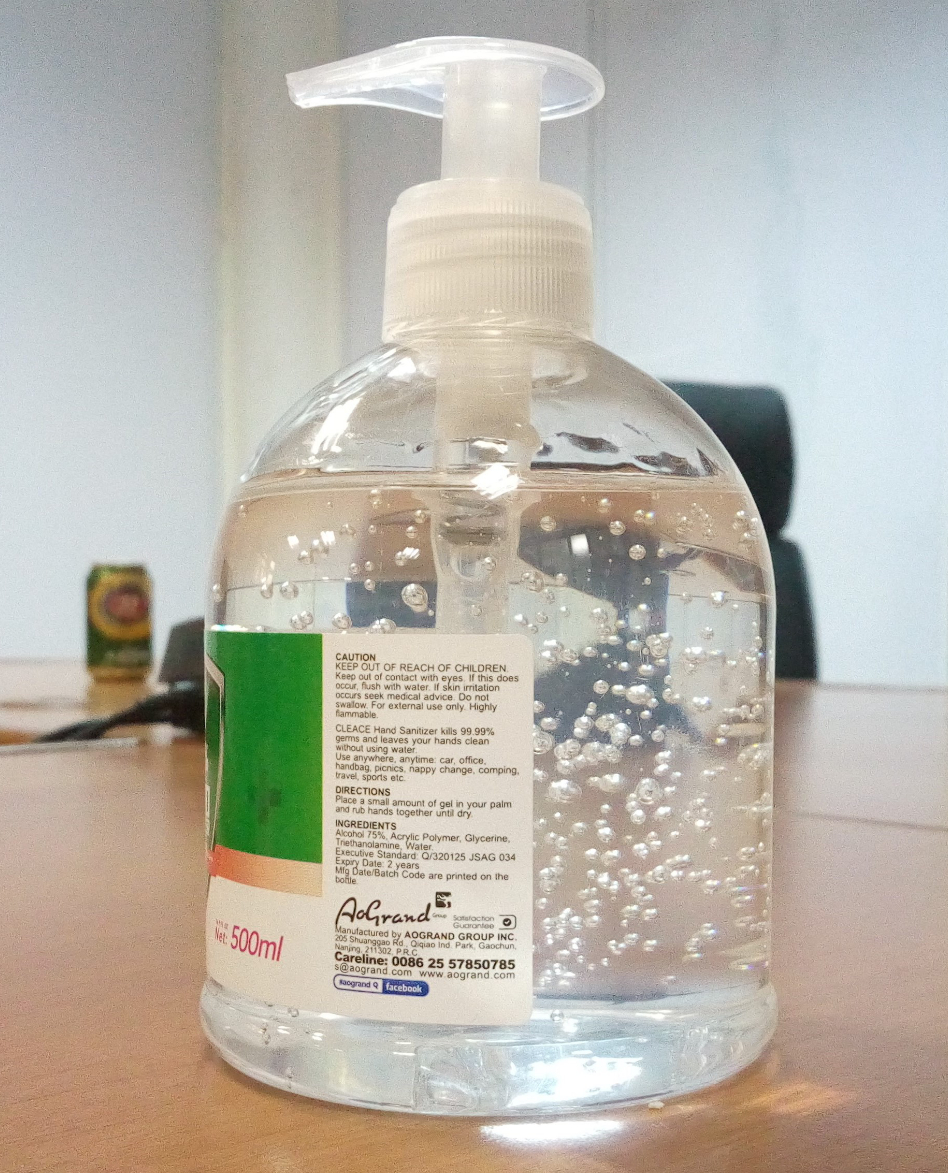

Hand sanitizer

View on Wikipedia

A typical pump bottle dispenser of hand sanitizer gel | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hand sanitizer, hand antiseptic,[1] hand disinfectant, hand rub, handrub[2] |

Hand sanitizer (also known as hand antiseptic, hand disinfectant, hand rub, or handrub) is a liquid, gel, or foam used to kill viruses, bacteria, and other microorganisms on the hands.[3][4] It can also come in the form of a cream, spray, or wipe.[5] While hand washing with soap and water is generally preferred,[6] hand sanitizer is a convenient alternative in settings where soap and water are unavailable. However, it is less effective against certain pathogens like norovirus and Clostridioides difficile and cannot physically remove harmful chemicals.[6] Improper use, such as wiping off sanitizer before it dries, can also reduce its effectiveness, and some sanitizers with low alcohol concentrations are less effective.[6] Additionally, frequent use of hand sanitizer may disrupt the skin's microbiome and cause dermatitis.[7]

Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, which contain at least 60% alcohol (ethanol or isopropyl alcohol), are recommended by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) when soap and water are not available.[8] In healthcare settings, these sanitizers are often preferred over hand washing with soap and water because they are more effective at reducing bacteria and are better tolerated by the skin.[9][10] However, hand washing should still be performed if contamination is visible or after using the toilet.[11] Non-alcohol-based hand sanitizers, which may contain benzalkonium chloride or triclosan, are less effective and generally not recommended,[9] though they are not flammable.[5]

The formulation of alcohol-based hand sanitizers typically includes a combination of isopropyl alcohol, ethanol, or n-propanol, with alcohol concentrations ranging from 60% to 95% being the most effective.[4] These sanitizers are flammable[9] and work against a wide variety of microorganisms, but not spores.[4] To prevent skin dryness, compounds such as glycerol may be added, and some formulations include fragrances, though these are discouraged due to the risk of allergic reactions.[12] Non-alcohol-based versions are less effective and should be used with caution.[13][14][15]

The use of alcohol as an antiseptic dates back to at least 1363, with evidence supporting its use emerging in the late 1800s.[16] Alcohol-based hand sanitizers became commonly used in Europe by the 1980s[17] and have since been included on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[18][19]

Uses

[edit]General public

[edit]Alcohol-based hand sanitizers may not be effective if the hands are slimy, greasy or visibly soiled. In hospitals, the hands of healthcare workers are often contaminated with pathogens, but rarely soiled or greasy.

Some commercially available hand sanitizers (and online recipes for homemade rubs) have alcohol concentrations that are too low.[20] This makes them less effective at killing germs.[6] Poorer people in developed countries[20] and people in developing countries may find it harder to get a hand sanitizer with an effective alcohol concentration.[21] Fraudulent labelling of alcohol concentrations has been a problem in Guyana.[22]

Schools

[edit]The current evidence that the effectiveness of school hand hygiene interventions is of poor quality.[23]

In a 2020 Cochrane review comparing rinse-free hand washing to conventional soap and water techniques and the subsequent impact on school absenteeism found a small but beneficial effect on rinse-free hand washing on illness related absenteeism.[24]

Health care

[edit]

Hand sanitizers were first introduced in 1966 in medical settings such as hospitals and healthcare facilities. The product was popularized in the early 1990s.[25]

Alcohol-based hand sanitizer is more convenient compared to hand washing with soap and water in most situations in the healthcare setting.[9] Among healthcare workers, it is generally more effective for hand antisepsis, and better tolerated than soap and water.[4] Hand washing should still be carried out if contamination can be seen or following the use of the toilet.[11]

Hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol or contains a "persistent antiseptic" should be used.[26][27] Alcohol rubs kill many different kinds of bacteria, including antibiotic resistant bacteria and TB bacteria. They also kill many kinds of viruses, including the flu virus, the common cold virus, coronaviruses, and HIV.[28][29]

90% alcohol rubs are more effective against viruses than most other forms of hand washing.[30] Isopropyl alcohol will kill 99.99% or more of all non-spore forming bacteria in less than 30 seconds, both in the laboratory and on human skin.[26][31]

In too low quantities (0.3 ml) or concentrations (below 60%), the alcohol in hand sanitizers may not have the 10–15 seconds exposure time required to denature proteins and lyse cells.[4] In environments with high lipids or protein waste (such as food processing), the use of alcohol hand rubs alone may not be sufficient to ensure proper hand hygiene.[4]

For health care settings, like hospitals and clinics, optimum alcohol concentration to kill bacteria is 70% to 95%.[32][33] Products with alcohol concentrations as low as 40% are available in American stores, according to researchers at East Tennessee State University.[34]

Alcohol rub sanitizers kill most bacteria, and fungi, and stop some viruses. Alcohol rub sanitizers containing at least 70% alcohol (mainly ethyl alcohol) kill 99.9% of the bacteria on hands 30 seconds after application and 99.99% to 99.999%[note 1] in one minute.[30]

For health care, optimal disinfection requires attention to all exposed surfaces such as around the fingernails, between the fingers, on the back of the thumb, and around the wrist. Hand alcohol should be thoroughly rubbed into the hands and on the lower forearm for a duration of at least 30 seconds and then allowed to air dry.[35]

Use of alcohol-based hand gels dries skin less, leaving more moisture in the epidermis, than hand washing with antiseptic/antimicrobial soap and water.[36][37][38][39]

Hand sanitizers containing a minimum of 60 to 95% alcohol are efficient germ killers. Alcohol rub sanitizers kill bacteria, multi-drug resistant bacteria (MRSA and VRE), tuberculosis, and some viruses (including HIV, herpes, RSV, rhinovirus, vaccinia, influenza,[40] and hepatitis) and fungi. Alcohol rub sanitizers containing 70% alcohol kill 99.97% (3.5 log reduction, similar to 35 decibel reduction) of the bacteria on hands 30 seconds after application and 99.99% to 99.999% (4 to 5 log reduction) of the bacteria on hands 1 minute after application.[30]

Drawbacks

[edit]There are certain situations during which hand washing with soap and water are preferred over hand sanitizer, these include: eliminating bacterial spores of Clostridioides difficile, parasites such as Cryptosporidium, and certain viruses like norovirus depending on the concentration of alcohol in the sanitizer (95% alcohol was seen to be most effective in eliminating most viruses).[41] In addition, if hands are contaminated with fluids or other visible contaminates, hand washing is preferred as well as after using the toilet and if discomfort develops from the residue of alcohol sanitizer use.[42] Furthermore, CDC states hand sanitizers are not effective in removing chemicals such as pesticides.[43]

Safety

[edit]Fire

[edit]Alcohol gel can catch fire, producing a translucent blue flame. This is due to the flammable alcohol in the gel. Some hand sanitizer gels may not produce this effect due to a high concentration of water or moisturizing agents. There have been some rare instances where alcohol has been implicated in starting fires in the operating room, including a case where alcohol used as an antiseptic pooled under the surgical drapes in an operating room and caused a fire when a cautery instrument was used. Alcohol gel was not implicated.[citation needed]

To minimize the risk of fire, alcohol rub users are instructed to rub their hands until dry, which indicates that the flammable alcohol has evaporated.[44] Igniting alcohol hand rub while using it is rare, but the need for this is underlined by one case of a health care worker using hand rub, removing a polyester isolation gown, and then touching a metal door while her hands were still wet; static electricity produced an audible spark and ignited the hand gel.[4]: 13 Hand sanitizer should be stored in temperatures below 105 °F and should not be left in a car during hot weather due to risk of flammability.[45] Fire departments suggest refills for the alcohol-based hand sanitizers can be stored with cleaning supplies away from heat sources or open flames.[46][47]

Skin

[edit]Researchers have not thoroughly studied the implications of hand sanitizer use for the body and the microbiome.[7] Studies of healthcare workers have correlated high rates of hand eczema with hand sanitizer use.[48][49]

The alcohol in hand sanitizer strips the skin of the outer layer of oil, which may have negative effects on barrier function of the skin. A study also shows that disinfecting hands with an antimicrobial detergent results in a greater barrier disruption of skin compared to alcohol solutions, suggesting an increased loss of skin lipids.[50][51]

Frequent use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers can cause dry skin unless emollients and/or skin moisturizers are added to the formula. The drying effect of alcohol can be reduced or eliminated by adding glycerin and/or other emollients to the formula.[52] In clinical trials, alcohol-based hand sanitizers containing emollients caused substantially less skin irritation and dryness than soaps or antimicrobial detergents. Allergic contact dermatitis, contact urticaria syndrome or hypersensitivity to alcohol or additives present in alcohol hand rubs rarely occur.[31] The lower tendency to induce irritant contact dermatitis became an attraction as compared to soap and water hand washing.

Ingestion

[edit]In the United States, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) controls antimicrobial handsoaps and sanitizers as over-the-counter drugs (OTC) because they are intended for topical anti-microbial use to prevent disease in humans.[53]

The FDA requires strict labeling which informs consumers on proper use of this OTC drug and dangers to avoid, including warning adults not to ingest, not to use in the eyes, to keep out of the reach of children, and to allow use by children only under adult supervision.[54] According to the American Association of Poison Control Centers, there were nearly 12,000 cases of hand sanitizer ingestion in 2006.[55] If ingested, alcohol-based hand sanitizers can cause alcohol poisoning in small children.[56] However, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control recommends using hand sanitizer with children to promote good hygiene, under supervision, and furthermore recommends parents pack hand sanitizer for their children when traveling, to avoid their contracting disease from dirty hands.[57]

Denaturants are an ingredient added to hand sanitizers, such as Purell, that is used to stop the liquid gel from being digested. This chemical adds a taste to the gel that makes it less enticing to consume. It is especially helpful in keeping younger children away because of the different smells and colors of hand sanitizers that tend to attract children.[58][59]

People with alcoholism may attempt to consume hand sanitizer in desperation when traditional alcoholic beverages are unavailable, or personal access to them is restricted by force or law. There have been reported incidents of people drinking the gel in prisons and hospitals to become intoxicated. As a result, access to sanitizing liquids and gels is controlled and restricted in some facilities.[60][61][62] For example, over a period of several weeks during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Mexico, seven people in that U.S. state who were alcoholic were severely injured by drinking sanitizer: three died, three were in critical condition, and one was left permanently blind.[63][64]

In 2021, a dozen children were hospitalized in the state of Maharashtra, India, after they were mistakenly orally administered hand sanitizer instead of a polio vaccine.[65]

Absorption

[edit]On 30 April 2015, the FDA announced that they were requesting more scientific data based on the safety of hand sanitizer. Emerging science suggests that for at least some health care antiseptic active ingredients, systemic exposure (full body exposure as shown by detection of antiseptic ingredients in the blood or urine) is higher than previously thought, and existing data raise potential concerns about the effects of repeated daily human exposure to some antiseptic active ingredients. This would include hand antiseptic products containing alcohol and triclosan.[66]

Surgical hand disinfection

[edit]Hands must be disinfected before any surgical procedure by hand washing with mild soap and then hand-rubbing with a sanitizer. Surgical disinfection requires a larger dose of the hand-rub and a longer rubbing time than is ordinarily used. It is usually done in two applications according to specific hand-rubbing techniques, EN1499 (hygienic handwash), and German standard DIN EN 1500 (hygienic hand disinfection) to ensure that antiseptic is applied everywhere on the surface of the hand.[67]

Alcohol-free

[edit]

Some hand sanitizer products use agents other than alcohol to kill microorganisms, such as povidone-iodine, benzalkonium chloride or triclosan.[4] The World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC recommends "persistent" antiseptics for hand sanitizers.[68] Persistent activity is defined as the prolonged or extended antimicrobial activity that prevents or inhibits the proliferation or survival of microorganisms after application of the product. This activity may be demonstrated by sampling a site several minutes or hours after application and demonstrating bacterial antimicrobial effectiveness when compared with a baseline level. This property also has been referred to as "residual activity." Both substantive and nonsubstantive active ingredients can show a persistent effect if they substantially lower the number of bacteria during the wash period.

Laboratory studies have shown lingering benzalkonium chloride may be associated with antibiotic resistance in MRSA.[69][70] Tolerance to alcohol sanitizers may develop in fecal bacteria.[71][72] Where alcohol sanitizers utilize 62%, or higher, alcohol by weight, only 0.1 to 0.13% of benzalkonium chloride by weight provides equivalent antimicrobial effectiveness.

Triclosan has been shown to accumulate in biosolids in the environment, one of the top seven organic contaminants in waste water according to the National Toxicology Program[73] Triclosan leads to various problems with natural biological systems,[74] and triclosan, when combined with chlorine e.g. from tap water, produces dioxins, a probable carcinogen in humans.[75] However, 90–98% of triclosan in waste water biodegrades by both photolytic or natural biological processes or is removed due to sorption in waste water treatment plants. Numerous studies show that only very small traces are detectable in the effluent water that reaches rivers.[76]

A series of studies show that photodegradation of triclosan produced 2,4-dichlorophenol and 2,8-dichlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (2,8-DCDD). The 2,4-dichlorophenol itself is known to be biodegradable as well as photodegradable.[77] For DCDD, one of the non-toxic compounds of the dioxin family,[78] a conversion rate of 1% has been reported and estimated half-lives suggest that it is photolabile as well.[79] The formation-decay kinetics of DCDD are also reported by Sanchez-Prado et al. (2006) who claim "transformation of triclosan to toxic dioxins has never been shown and is highly unlikely."[80]

Alcohol-free hand sanitizers may be effective immediately while on the skin, but the solutions themselves can become contaminated because alcohol is an in-solution preservative and without it, the alcohol-free solution itself is susceptible to contamination. However, even alcohol-containing hand sanitizers can become contaminated if the alcohol content is not properly controlled or the sanitizer is grossly contaminated with microorganisms during manufacture. In June 2009, alcohol-free Clarcon Antimicrobial Hand Sanitizer was pulled from the US market by the FDA, which found the product contained gross contamination of extremely high levels of various bacteria, including those which can "cause opportunistic infections of the skin and underlying tissues and could result in medical or surgical attention as well as permanent damage". Gross contamination of any hand sanitizer by bacteria during manufacture will result in the failure of the effectiveness of that sanitizer and possible infection of the treatment site with the contaminating organisms.[81]

Types

[edit]Alcohol-based hand rubs are extensively used in the hospital environment as an alternative to antiseptic soaps. Hand-rubs in the hospital environment have two applications: hygienic hand rubbing and surgical hand disinfection. Alcohol based hand rubs provide a better skin tolerance as compared to antiseptic soap.[39] Hand rubs also prove to have more effective microbiological properties as compared to antiseptic soaps.

The same ingredients used in over-the-counter hand-rubs are also used in hospital hand-rubs: alcohols such as ethanol and isopropanol, sometimes combined with quaternary ammonium cations (quats) such as benzalkonium chloride. Quats are added at levels up to 200 parts per million to increase antimicrobial effectiveness. Although allergy to alcohol-only rubs is rare, fragrances, preservatives and quats can cause contact allergies.[82] These other ingredients do not evaporate like alcohol and accumulate leaving a "sticky" residue until they are removed with soap and water.

The most common brands of alcohol hand rubs include Aniosgel, Avant, Sterillium, Desderman and Allsept S. All hospital hand rubs must conform to certain regulations like EN 12054 for hygienic treatment and surgical disinfection by hand-rubbing. Products with a claim of "99.99% reduction" or 4-log reduction are ineffective in hospital environment, since the reduction must be more than "99.99%".[30]

The hand sanitizer dosing systems for hospitals are designed to deliver a measured amount of the product for staff. They are dosing pumps screwed onto a bottle or are specially designed dispensers with refill bottles. Dispensers for surgical hand disinfection are usually equipped with elbow controlled mechanism or infrared sensors to avoid any contact with the pump.

Composition

[edit]Consumer alcohol-based hand sanitizers, and health care "hand alcohol" or "alcohol hand antiseptic agents" exist in liquid, foam, and easy-flowing gel formulations. Products with 60% to 95% alcohol by volume are effective antiseptics. Lower or higher concentrations are less effective; most products contain between 60% and 80% alcohol.[83]

In addition to alcohol (ethanol, isopropanol or n-Propanol), hand sanitizers also contain the following:[83]

- additional antiseptics such as chlorhexidine and quaternary ammonium derivatives,

- sporicides such as hydrogen peroxides that eliminate bacterial spores that may be present in ingredients,

- emollients and gelling agents to reduce skin dryness and irritation,

- a small amount of sterile or distilled water,

- sometimes foaming agents, colorants or fragrances.

WHO formulations

[edit]The World Health Organization has published the following formulations to guide to the production of large quantities of hand sanitizer from chemicals available in developing countries, where commercial hand sanitizer may not be available:[2]

Formulation 1

[edit]| Ingredient | Volume required (10-L prep.) | Active ingredient % (v/v) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol 96% | 8333 mL | 80% |

| Glycerol 98% | 145 mL | 1.45% |

| Hydrogen peroxide 3% | 417 mL | 0.125% |

| Distilled water | added to 10000 mL | 18.425% |

Formulation 2

[edit]| Ingredient | Volume required (10-L prep.) | Active ingredient % (v/v) |

|---|---|---|

| Isopropyl alcohol 99.8% | 7515 mL | 75% |

| Glycerol | 145 mL | 1.45% |

| Hydrogen peroxide 3% | 417 mL | 0.125% |

| Distilled water | added to 10000 mL | 23.425% |

Production

[edit]COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]

In 2010 the World Health Organization produced a guide for manufacturing hand sanitizer, which received renewed interest in 2020 because of shortages of hand sanitizer in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[2] Dozens of liquor and perfume manufacturers switched their manufacturing facilities from their normal product to hand sanitizer.[84] In order to keep up with the demand, local distilleries started using their alcohol to make hand sanitizer.[85] Distilleries producing hand sanitizer originally existed in a legal grey area in the United States, until the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau declared that distilleries could produce their sanitizer without authorization.[86][87]

In the beginnings of the pandemic, because of hand sanitizer shortages due to panic buying, people resorted to using 60% to 99% concentrations of isopropyl or ethyl alcohol for hand sanitization, typically mixing them with glycerol or soothing moisturizers or liquid contain aloe vera to counteract irritations with options of adding drops of lemon or lime juice or essential oils for scents, and thus making DIY hand sanitizers.[88] However, there are cautions against making them, such as a wrong measurement or ingredient may resulting in an insufficient amount of alcohol to kill the coronavirus, thus rendering the mixture ineffective or even poisonous.[89]

Additionally, some commercial products are dangerous, either due to poor oversight and process control, or fraudulent motive. In June 2020, the FDA issued an advisory against use of hand sanitizer products manufacture by Eskbiochem SA de CV in Mexico due to excessive levels of methanol – up to 81% in one product. Methanol can be absorbed through the skin, is toxic in modest amounts, and in substantial exposure can result in "nausea, vomiting, headache, blurred vision, permanent blindness, seizures, coma, permanent damage to the nervous system or death".[90] Products suspected of manufacture by Eskbiochem SA with excessive methanol have been reported as far away as British Columbia, Canada.[91]

In August 2020, the FDA expanded the list of dangerous hand sanitizers.[92][93]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Medical research papers sometimes use "n-log" to mean a reduction of n on a (base 10) logarithmic scale graphing the number of bacteria, thus "5-log" means a reduction by a factor of 105, or 99.999%

Sources

[edit]- ^ "Tentative Final Monograph for Health-Care Antiseptic Drug Products; Proposed Rule" (PDF). United States Federal Food and Drug Administration. March 2009. pp. 12613–12617. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Guide to Local Production: WHO-recommended Handrub Formulations (Report). WHO. April 2010. Archived from the original on 2022-10-27. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ "hand sanitizer - definition of hand sanitizer in English". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Boyce JM, Pittet D (October 2002). "Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America" (PDF). MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 51 (RR-16): 1–45, quiz CE1–4. PMID 12418624.

- ^ a b Jing JL, Pei Yi T, Bose RJ, McCarthy JR, Tharmalingam N, Madheswaran T (May 2020). "Hand Sanitizers: A Review on Formulation Aspects, Adverse Effects, and Regulations". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (9): 3326. doi:10.3390/ijerph17093326. PMC 7246736. PMID 32403261.

- ^ a b c d "Show Me the Science – When & How to Use Hand Sanitizer in Community Settings". cdc.gov. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

CDC recommends washing hands with soap and water whenever possible because hand washing reduces the amounts of all types of germs and chemicals on hands. But if soap and water are not available, using a hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol can help... sanitizers do not eliminate all types of germs... Hand sanitizers may not be as effective when hands are visibly dirty or greasy... Hand sanitizers might not remove harmful chemicals

- ^ a b Bhatt S, Patel A, Kesselman MM, Demory ML (June 2024). "Hand Sanitizer: Stopping the Spread of Infection at a Cost". Cureus. 16 (6) e61846. doi:10.7759/cureus.61846. PMC 11227450. PMID 38975405.

- ^ "Clean Hands Save Lives!". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 December 2013. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Bolon MK (September 2016). "Hand Hygiene: An Update". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 30 (3): 591–607. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2016.04.007. PMID 27515139.

In 2002, the CDC released an updated hand hygiene guideline and, for the first time, endorsed the use of alcohol-based hand rubs for the majority of clinical interactions, provided that hands are not visibly soiled

- ^ Hirose R, Nakaya T, Naito Y, Daidoji T, Bandou R, Inoue K, et al. (September 2019). "Situations Leading to Reduced Effectiveness of Current Hand Hygiene against Infectious Mucus from Influenza Virus-Infected Patients". mSphere. 4 (5) e00474-19. doi:10.1128/mSphere.00474-19. PMC 6751490. PMID 31533996.

For many reasons, alcohol hand sanitizers are increasingly being used as disinfectants over hand washing with soap and water. Their ease of availability, no need for water or plumbing, and their proven effectiveness in reducing microbial load are just a few.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2015). The selection and use of essential medicines. Twentieth report of the WHO Expert Committee 2015 (including 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and 5th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/189763. ISBN 978-92-4-069494-1. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series; no. 994.

- ^ "Guide to Local Production: WHO-recommended Handrub Formulations" (PDF). Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Long BW, Rollins JH, Smith BJ (2015). Merrill's Atlas of Radiographic Positioning and Procedures (13th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-323-31965-2. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- ^ Baki G, Alexander KS (2015). Introduction to Cosmetic Formulation and Technology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-118-76378-0. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Alcohol-free hand sanitizer prices are skyrocketing, but they don't actually work to prevent the coronavirus, Business Insider - Business Insider Singapore". www.businessinsider.sg. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Block SS (1977-12-01). "Disinfection, sterilization, and preservation". Soil Science. 124 (6): 378. Bibcode:1977SoilS.124..378B. doi:10.1097/00010694-197712000-00013. ISSN 0038-075X.

- ^ Miller CH, Palenik CJ (2016). Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-323-47657-7. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ a b Reynolds SA, Levy F, Walker ES (March 2006). "Hand sanitizer alert". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (3): 527–529. doi:10.3201/eid1203.050955. PMC 3291447. PMID 16710985.

- ^ Okafor W (31 March 2020). "COVID-19: Not all hand sanitizers can kill virus — Pharmacist". InsideMainland. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020.

- ^ "Purcill Hand Sanitizer being recalled for low alcohol content". News Source Guyana. 9 April 2020.

- ^ Willmott M, Nicholson A, Busse H, MacArthur GJ, Brookes S, Campbell R (January 2016). "Effectiveness of hand hygiene interventions in reducing illness absence among children in educational settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 101 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-308875. PMC 4717429. PMID 26471110.

- ^ Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Lockwood C, Stern C, McAneney H, Barker TH (April 2020). "Rinse-free hand wash for reducing absenteeism among preschool and school children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (4) CD012566. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012566.pub2. PMC 7141998. PMID 32270476.

- ^ "Origin of ordinary things: Hand sanitizer". The New Times. Rwanda. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Handwashing in Communities: Clean Hands Save Lives | CDC". www.cdc.gov. October 3, 2022. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017.

- ^ "Dirty Hands Spread Dangerous Diseases like H1N1 (aka swine flu)". San Jose Mercury News. 25 April 2009.

- ^ Trampuz A, Widmer AF (January 2004). "Hand hygiene: a frequently missed lifesaving opportunity during patient care". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 79 (1): 109–116. doi:10.4065/79.1.109. PMC 7094481. PMID 14708954.

alcohol effectively kills all coronaviruses. The virucidal activity of alcohol against enveloped viruses (such as influenza virus or human immunodeficiency virus) is good, except for rabies virus.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Rotter ML (1999). "Handwashing and hand disinfection". In Mayhall CG (ed.). Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-30608-8.

- ^ a b Hibbard JS (May–June 2005). "Analyses comparing the antimicrobial activity and safety of current antiseptic agents: a review". Journal of Infusion Nursing. 28 (3): 194–207. doi:10.1097/00129804-200505000-00008. PMID 15912075. S2CID 5555893.

- ^ Kramer A, Rudolph P, Kampf G, Pittet D (April 2002). "Limited efficacy of alcohol-based hand gels". Lancet. 359 (9316): 1489–1490. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08426-X. PMID 11988252. S2CID 30450670.

- ^ Pietsch H (August 2001). "Hand antiseptics: rubs versus scrubs, alcoholic solutions versus alcoholic gels". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 48 (Supl A): S33 – S36. doi:10.1016/S0195-6701(01)90010-6. PMID 11759022.

- ^ Reynolds SA, Levy F, Walker ES (March 2006). "Hand sanitizer alert". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (3): 527–529. doi:10.3201/eid1203.050955. PMC 3291447. PMID 16710985. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ Girou E, Loyeau S, Legrand P, Oppein F, Brun-Buisson C (August 2002). "Efficacy of handrubbing with alcohol based solution versus standard handwashing with antiseptic soap: randomised clinical trial". BMJ. 325 (7360): 362. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7360.362. PMC 117885. PMID 12183307. Archived from the original on 27 November 2009.

- ^ Pedersen LK, Held E, Johansen JD, Agner T (December 2005). "Less skin irritation from alcohol-based disinfectant than from detergent used for hand disinfection". The British Journal of Dermatology. 153 (6): 1142–1146. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06875.x. PMID 16307649. S2CID 46265931. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021.

- ^ Pedersen LK, Held E, Johansen JD, Agner T (February 2005). "Short-term effects of alcohol-based disinfectant and detergent on skin irritation". Contact Dermatitis. 52 (2): 82–87. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00504.x. PMID 15725285. S2CID 24691060.

- ^ Boyce JM (July 2000). "Using alcohol for hand antisepsis: dispelling old myths". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 21 (7): 438–441. doi:10.1086/501784. PMID 10926392.

- ^ a b Boyce JM, Kelliher S, Vallande N (July 2000). "Skin irritation and dryness associated with two hand-hygiene regimens: soap-and-water hand washing versus hand antisepsis with an alcoholic hand gel". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 21 (7): 442–448. doi:10.1086/501785. PMID 10926393. S2CID 22772488.

- ^ Larson EL, Cohen B, Baxter KA (November 2012). "Analysis of alcohol-based hand sanitizer delivery systems: efficacy of foam, gel, and wipes against influenza A (H1N1) virus on hands". American Journal of Infection Control. 40 (9): 806–809. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2011.10.016. PMID 22325728.

- ^ Gold NA, Mirza TM, Avva U (2018). "Alcohol Sanitizer". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30020626.

- ^ Seal K, Cimon K, Argáez C (9 March 2017). Summary of Evidence. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

- ^ "When & How to Wash Your Hands". cdc.gov. 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Alcohol-Based Hand-Rubs and Fire Safety". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 September 2003. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- ^ "Q&A for Consumers | Hand Sanitizers and COVID-19". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2023-05-12.

- ^ "1301:7-7-3405.5". Ohio Administrative Code.

- ^ "Craftex 5 Litre Hand Sanitiser Gel". AES Industrial Supplies Limited. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ MacGibeny MA, Wassef C (August 2021). "Preventing adverse cutaneous reactions from amplified hygiene practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: how dermatologists can help through anticipatory guidance". Archives of Dermatological Research. 313 (6): 501–503. doi:10.1007/s00403-020-02086-x. PMC 7210798. PMID 32388643.

- ^ Emami A, Javanmardi F, Keshavarzi A, Pirbonyeh N (July 2020). "Hidden threat lurking behind the alcohol sanitizers in COVID-19 outbreak". Dermatologic Therapy. 33 (4) e13627. doi:10.1111/dth.13627. PMC 7280687. PMID 32436262.

- ^ Löffler H, Kampf G (October 2008). "Hand disinfection: how irritant are alcohols?". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 70 (Suppl 1): 44–48. doi:10.1016/S0195-6701(08)60010-9. PMID 18994681.

- ^ Pedersen LK, Held E, Johansen JD, Agner T (December 2005). "Less skin irritation from alcohol-based disinfectant than from detergent used for hand disinfection". The British Journal of Dermatology. 153 (6): 1142–1146. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06875.x. PMID 16307649. S2CID 46265931.

- ^ Menegueti MG, Laus AM, Ciol MA, Auxiliadora-Martins M, Basile-Filho A, Gir E, et al. (2019-06-24). "Glycerol content within the WHO ethanol-based handrub formulation: balancing tolerability with antimicrobial efficacy". Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 8 (1) 109. doi:10.1186/s13756-019-0553-z. PMC 6591802. PMID 31285821.

- ^ Wagner DS (2000). "GENERAL GUIDE TO CHEMICAL CLEANING PRODUCT REGULATION" (PDF). International Sanitary Supply Association, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2009.

- ^ Foulke JE (May 1994). "Decoding the Cosmetic Label". FDA Consumer Magazine.

- ^ "Paging Dr. Gupta, Hand sanitizer risks". CNN. 21 June 2007. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009.

- ^ "Hand Sanitizers Could Be A Dangerous Poison To Unsupervised Children". NBC News Channel. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "International Travel with Infants and Young Children". Travelers' Health – Yellow Book. 8. March 2009.

- ^ "PURELL Hand Sanitizer Ingredients". www.gojo.com. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ "It's the Season for Hand Sanitizer. Should You Replace Old Bottles?". Health. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ Gormley NJ, Bronstein AC, Rasimas JJ, Pao M, Wratney AT, Sun J, et al. (January 2012). "The rising incidence of intentional ingestion of ethanol-containing hand sanitizers". Critical Care Medicine. 40 (1): 290–294. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822f09c0. PMC 3408316. PMID 21926580.

- ^ "Prisoner 'drunk on swine flu gel'". BBC News online. 24 September 2009.

- ^ Don't Drink the Hand Sanitizer Archived 14 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine NY Times Retrieved March 2017

- ^ Karimi F (27 June 2020). "Three people died and one is permanently blind after drinking hand sanitizer in New Mexico". CNN. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Yip L, Bixler D, Brooks DE, Clarke KR, Datta SD, Dudley S, et al. (August 2020). "Serious Adverse Health Events, Including Death, Associated with Ingesting Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizers Containing Methanol - Arizona and New Mexico, May-June 2020". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (32): 1070–1073. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e1. PMC 7440116. PMID 32790662.

- ^ Pratap RM, Guy J (2 February 2021). "Indian children hospitalized after ingesting hand sanitizer instead of polio drops". CNN. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "FDA issues proposed rule to address data gaps for certain active ingredients in health care antiseptics". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015.

- ^ Kampf G, Ostermeyer C (April 2003). "Inter-laboratory reproducibility of the hand disinfection reference procedure of EN 1500". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 53 (4): 304–306. doi:10.1053/jhin.2002.1357. PMID 12660128.

- ^ "Do hand sanitizers really work?". University of Toronto News. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ AKimitsu N, Hamamoto H, Inoue R, Shoji M, Akamine A, Takemori K, et al. (December 1999). "Increase in resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to beta-lactams caused by mutations conferring resistance to benzalkonium chloride, a disinfectant widely used in hospitals". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 43 (12): 3042–3043. doi:10.1128/AAC.43.12.3042. PMC 89614. PMID 10651623.

- ^ "Antibacterial Household Products: Cause for Concern". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 16 August 2001. Retrieved 1 June 2001.

- ^ Davis N (1 August 2018). "Bacteria becoming resistant to hospital disinfectants, warn scientists". The Guardian.

- ^ Pidot SJ, Gao W, Buultjens AH, Monk IR, Guerillot R, Carter GP, et al. (August 2018). "Increasing tolerance of hospital Enterococcus faecium to handwash alcohols". Science Translational Medicine. 10 (452) eaar6115. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aar6115. PMID 30068573.

- ^ "Hand NTP Research Concept: Triclosan" (PDF). National Toxicology Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ McMurry LM, Oethinger M, Levy SB (August 1998). "Triclosan targets lipid synthesis". Nature. 394 (6693): 531–532. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..531M. doi:10.1038/28970. PMID 9707111. S2CID 4365434.

- ^ "Environmental Emergence of Triclosan" (PDF). Santa Clara Basin Watershed Management Initiative. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2006.

- ^ Heidler J, Halden RU (January 2007). "Mass balance assessment of triclosan removal during conventional sewage treatment". Chemosphere. 66 (2): 362–369. Bibcode:2007Chmsp..66..362H. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.066. PMID 16766013.

- ^ Capdevielle M, Van Egmond R, Whelan M, Versteeg D, Hofmann-Kamensky M, Inauen J, et al. (January 2008). "Consideration of exposure and species sensitivity of triclosan in the freshwater environment". Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. 4 (1): 15–23. Bibcode:2008IEAM....4...15C. doi:10.1897/ieam_2007-022.1. PMID 18260205. S2CID 28986794.

- ^ Wisk JD, Cooper KR (1990). "Comparison of the toxicity of several polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzofuran in embryos of the Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes)". Chemosphere. 20 (3–4): 361–377. Bibcode:1990Chmsp..20..361W. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(90)90067-4.

- ^ Aranami K, Readman JW (January 2007). "Photolytic degradation of triclosan in freshwater and seawater". Chemosphere. 66 (6): 1052–6. Bibcode:2007Chmsp..66.1052A. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.07.010. PMID 16930676.

- ^ Sanchez-Prado L, Llompart M, Lores M, García-Jares C, Bayona JM, Cela R (November 2006). "Monitoring the photochemical degradation of triclosan in wastewater by UV light and sunlight using solid-phase microextraction". Chemosphere. 65 (8): 1338–1347. Bibcode:2006Chmsp..65.1338S. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.025. PMID 16735047.

- ^ "Consumers Warned Not to Use Clarcon Skin Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ de Groot AC (July 1987). "Contact allergy to cosmetics: causative ingredients". Contact Dermatitis. 17 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1987.tb02640.x. PMID 3652687. S2CID 72677422.

- ^ a b Bonnabry P, Voss A (2017). "Hand Hygiene Agents". In Pittet D, Boyce JM, Allegranzi B (eds.). Hand Hygiene: a Handbook for Medical Professionals. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 51 et seq. ISBN 978-1-118-84686-5.

- ^ "White House Works With Distillers to Increase Hand Sanitizer Production", Forbes, 18 March 2020

- ^ Kaur H (16 March 2020). "Distilleries are making hand sanitizer with their in-house alcohol and giving it out for free to combat coronavirus". CNN. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Levenson M (19 March 2020). "Distilleries Race to Make Hand Sanitizer Amid Coronavirus Pandemic". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Production of Hand Sanitizer by Distilled Spirits Permittees". The TTB Newsletter. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, US Department of the Treasury. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "71° Store shelves wiped clean? Here's how you can make homemade hand sanitizer". Fox 6 Now. Fox Television Stations, LLC. 14 March 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Mitroff S. "No, you shouldn't make your own hand sanitizer". CNET. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "FDA advises consumers not to use hand sanitizer products manufactured by Eskbiochem". fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "British Columbians warned over hand sanitizers containing potentially toxic ingredient". richmond-news.com. Richmond News. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "FDA updates on hand sanitizers consumers should not use". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 5 August 2020. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

External links

[edit]- "Executive Summary: National Stakeholders Meeting on Alcohol-Based Hand-Rubs and Fire Safety in Health Care Facilities". American Hospital Association, Co-Hosted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) and AHA. 22 July 2003. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008.