Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hard palate

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

| Hard palate | |

|---|---|

Mouth (oral cavity) | |

Upper respiratory system, with hard palate labeled at right | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Greater palatine artery |

| Nerve | Greater palatine nerve, nasopalatine nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | palatum durum |

| MeSH | D021362 |

| TA98 | A05.1.01.103 |

| TA2 | 2779 |

| FMA | 55023 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

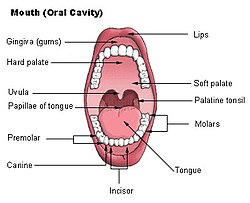

The hard palate is a thin horizontal bony plate made up of two bones of the facial skeleton, located in the roof of the mouth. The bones are the palatine process of the maxilla and the horizontal plate of palatine bone. The hard palate spans the alveolar arch formed by the alveolar process that holds the upper teeth (when these are developed).

Structure

[edit]The hard palate is formed by the palatine process of the maxilla and horizontal plate of palatine bone. It forms a partition between the nasal passages and the mouth. On the anterior portion of the hard palate are the plicae, irregular ridges in the mucous membrane that help hold food while the teeth are biting into it while also facilitating the movement of food backward towards the larynx once pieces have been bitten off. This partition is continued deeper into the mouth by a fleshy extension called the soft palate.

On the ventral surface of the hard palate, some projections or transverse ridges are present which are called palatine rugae.[1]

Function

[edit]The hard palate is important for feeding and speech. Mammals with a defective hard palate may die shortly after birth due to inability to suckle. It is also involved in mastication in many species. The interaction between the tongue and the hard palate is essential in the formation of certain speech sounds, notably high-front vowels, palatal consonants, and retroflex consonants such as [i] like "see", [j] like "yes", [ç] (realization of /hj/ in English) like "hue", and [ɻ] (/r/, only for some speakers) like "red".

Clinical significance

[edit]Cleft palate

[edit]In the birth defect called cleft palate, the left and right portions of this plate are not joined, forming a gap between the mouth and nasal passage (a related defect affecting the face is cleft lip).

While a cleft palate has a severe impact upon the ability to nurse and speak, it is now successfully treated through reconstructive surgical procedures at an early age. This is the time where such procedures are available.

Due to the complexity of this birth defect, researchers still do not know exactly what causes the cleft palate to form during foetal development. Recently, these researchers found that even though there is no exact cause, there are several factors that drastically increase the risk of a baby being born with an orofacial cleft palate. As for the environmental risk factors, maternal smoking is the most influential risk factor. Based on a recent study of 103 German patients with cleft palates, it was found that 25.2% of their mothers smoked during pregnancy, a higher proportion than for the population as a whole.[2]

While maternal smoking during pregnancy is a risk, there are also several genetic risk factors. Six single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the PAX7 gene are implicated in the development of facial features.[3] These variations occur at six loci: 1p36, 2p21, 3p11.1, 8q21.3, 13q31.1 and 15q22.[3] When tested in the European and Asian communities, five of the six loci had a significant association at the 95% confidence level.[3] Besides the PAX 7 gene variants, there were also five possible mutations found in the transforming growth factor-alpha gene (TGFA) that could lead to the development of a cleft palate.[4] Even though several risk factors have been linked to cleft palates, more research must be done in order to determine the true causes of the defect.

Palatal abscess

[edit]Palatal abscesses may also occur.[5]

Hard palate pigmentation

[edit]Long-term use of the drug chloroquine diphosphatase, used in malaria prophylaxis, rheumatoid arthritis and other conditions, was found to cause bluish-grey pigmentation in the hard palate.[6][7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Patil, Manashvini S.; Patil, Sanjayagouda B.; Acharya, Ashith B. (2008-11-01). "Palatine Rugae and Their Significance in Clinical Dentistry: A Review of the Literature". The Journal of the American Dental Association. 139 (11): 1471–1478. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0072. ISSN 0002-8177. PMID 18978384.

- ^ Reiter, Rudolf; Brosch, Sibylle; Luedeke, Manuel; Fischbein, Elena; Haase, S; Pickhard, A; Assum, G; Schwandt, A; Vogel, W; Maier, C; Hogel, J (April 2012). "Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Submucous Cleft Palate". European Journal of Oral Sciences. 120 (2): 97–103. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00948.x. PMID 22409215. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Ludwig, KU; Mangold, E; Herms, S; Nowak, S; Reutter, H; Paul, A; Becker, J; Herberz, R; AlChawa, T; Nasser, E; Bohmer, AC; Mattheisen, M; Alblas, MA; Barth, S; Kluck, N; Lauster, C; Braumann, B; Reich, RH; Hemprich, A; Pötzsch, S; Blaumeiser, B; Daratsianos, N; Kreusch, T; Murray, JC; Marazita, ML; Ruczinski, I; Scott, AF; Beaty, TH; Kramer, FJ; Wienker, TF; Steegers-Theunissen, RP; Rubini, M; Mossey, PA; Hoffman, P; Lange, C; Chichon, S; Propping, P; Knapp, M; Nothen, MM (Aug 5, 2012). "Genome-wide meta-analyses of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate identify six new risk loci". Nat Genet. 44 (9): 968–971. doi:10.1038/ng.2360. PMC 3598617. PMID 22863734.

- ^ Kohli, Sarvraj Singh; Kohli, Virinder Singh (Jan 2012). "A comprehensive review of the genetic basis of cleft lip and palate". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 16 (1): 64–72. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.92976. PMC 3303526. PMID 22438645.

- ^ Houston, GD; Brown, FH (October 1993). "Differential diagnosis of the palatal mass". Compendium (Newtown, Pa.). 14 (10): 1222–4, 1226, 1228–31, quiz 1232. PMID 8118828.

- ^ Manger, Karin; von Streitberg, Ulrich; Seitz, Gerhard; Kleyer, Arnd; Manger, Bernhard (2017-11-28). "Hard Palate Hyperpigmentation-a Rare Side Effect of Antimalarials". Arthritis & Rheumatology. 70 (1): 152. doi:10.1002/art.40327. ISSN 2326-5191. PMID 28941224.

- ^ de Andrade, Bruno-Augusto-Benevenuto; Padron-Alvarado, Nelson-Alejandro; Muñoz-Campos, Edgar-Manuel; Morais, Thayná-Melo-de Lima; Martinez-Pedraza, Ricardo (2017-12-01). "Hyperpigmentation of hard palate induced by chloroquine therapy". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 9 (12): e1487 – e1491. doi:10.4317/jced.54387. ISSN 1989-5488. PMC 5794129. PMID 29410767.