Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Harikatha

View on Wikipedia

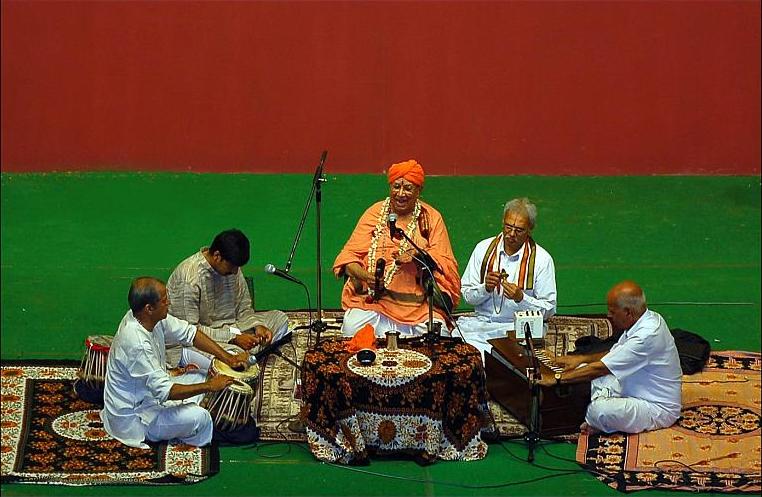

Harikatha (Kannada: ಹರಿಕಥೆ : Harikathe; Telugu: హరికథ : Harikatha; Marathi: हरीपाठ : Haripatha, lit. 'story of Hari'), also known as Harikatha Kaalakshepam in Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam(lit. 'spending time to listen to Hari's story'), is a form of Hindu traditional discourse in which the storyteller explores a traditional theme, usually the life of a saint or a story from an Indian epic. The person telling the story through songs, music and narration is called a Haridasa.

Harikatha is a composite art form composed of storytelling, poetry, music, drama, dance, and philosophy most prevalent in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala and ancient Tamil Nadu. Any Hindu religious theme may be the subject for the Harikatha. At its peak Harikatha was a popular medium of entertainment, which helped transmit cultural, educational and religious values to the masses. The main aim of Harikatha is to imbue truth and righteousness in the minds of people and sow the seeds of devotion in them. Another of the aims is to educate them about knowledge of Ātman (the self) through stories and show them the path of liberation.

Hindu mythology

[edit] | ||||||

| Music of India | ||||||

| Genres | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Traditional

Modern |

||||||

| Media and performance | ||||||

|

||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||

|

||||||

| Regional music | ||||||

|

||||||

In Hindu mythology, the first Harikatha singer was sage Narada who sang for Vishnu, other prominent singers were Lava and Kusha twin sons of Rama, who sang the Ramayana in his court at Ayodhya.[1]

History

[edit]This is an ancient form that took current form during the Bhakti movement in around 12th century. Many famous Haridasa are Purandaradasa, Kanakadasa.

The Telugu form of Harikatha originated in Coastal Andhra during the 19th century.[2] Harikatha Kalakshepam is most prevalent in Andhra even now along with Burra katha. Haridasus going round villages singing devotional songs is an age-old tradition during Dhanurmaasam preceding Sankranti festival. Ajjada Adibhatla Narayana Dasu was the originator of the Telugu Harikatha tradition, and with his Kavyas and Prabandhas has made it a special art form.[citation needed]

Style

[edit]Harikatha involves the narration of a story, intermingled with various songs relating to the story. Usually, the narration involves numerous sub-plots and anecdotes, which are used to emphasize various aspects of the main story. The main storyteller is usually assisted by one or more co-signers, who elaborate the songs and a Mridangam accompanist. The storyteller uses a pair of cymbals to keep the beat.

Famous exponents

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

Following Krishna Bhagavatar, other great exponents of this art form such as Pandit Lakshmanachar, Tirupazhanam Panchapakesa Bhagavatar, Mangudi Chidambara Bhagavatar, Muthiah Bhagavatar, Tiruvaiyyar Annasami Bhagavatar, Embar Srirangachariyar, Konnoor Sitarama Shastry, Sulamangalam Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar, Sulamangalam Soundararaja Bhagavatar, Ajjada Adibhatla Narayana Dasu, Embar Vijayaraghavachariar, Saraswati Bai and Padmasini Bai popularized the Harikatha tradition.[citation needed]

Saraswati Bai was a pioneering woman Harikatha exponent. She broke the monopoly of Brahmin men over this art form. This was attested by F. G. Natesa Iyer (in 1939) who said: "Saraswati Bai is a pioneer, and today, as a result of her sacrifices. Brahmins and non-Brahmins walk freely over the once forbidden ground. C. Saraswati Bai has achieved this miracle."[3]

Recent practitioners of Harikatha include Veeragandham Venkata Subbarao, Kota Sachchidananda Sastri, Mannargudi Sambasiva Bhagavatar, Banni Bai, Mysore Sreekantha Shastry, Kamala Murthy, Muppavarapu Simhachala Sastry, Embar Vijayaraghavachariar, Kalyanapuram Aravamudachariar, Vishaka hari, Gururajulu Naidu and T S Balakrishna Sastry.[citation needed]

Paruthiyur Krishna Sastri started out as a Harikatha exponent and then changed to Pravachan style.[citation needed] One of the best harikatha renderings is on the life of saint Tyagaraja by Mullukutla Sadasiva Sastry from Tenali.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Singh, p. 2118

- ^ Thoomati Donappa. Telugu Harikatha Sarvasvam. OCLC 13505520.

- ^ Deepa Ganesh (12 February 2015). "She paved the way". The Hindu. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

Sriram V. records F.G. Natesa Iyer (in 1939) as saying: "Saraswati Bai is a pioneer, and today, as a result of her sacrifices…. Brahmins and non-Brahmins walk freely over the once forbidden ground. C. Saraswati Bai has achieved this miracle."

References

[edit]- Singh, N.K. (1997). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Volume 3. Anmol Publications. ISBN 81-7488-168-9.

- Arnold, Alison (2000). "Kassebaum, Gayathri Rajapur.'Karnatak raga'". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent. New York & London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8240-4946-2.

- Harikatha: its origins and development, by Kalaimamani B. M. Sundaram. Publisher Vidwan R.K. Srikantan Trust, 2001.

- Datta, Amaresh (2006). The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Devraj To Jyoti), Volume 2. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 1551–1553. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

- Harikatha : Samarth Ramdas' Contribution to the Art of Spiritual Story-Telling by Meera Grimes. Indica Books, 2008. ISBN 81-86569-76-6.