Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heliand

View on Wikipedia

The Heliand (/ˈhɛliənd/) is an epic alliterative verse poem in Old Saxon, written in the first half of the 9th century. The title means "savior" in Old Saxon (cf. German and Dutch Heiland meaning "savior"), and the poem is a Biblical paraphrase that recounts the life of Jesus in the alliterative verse style of a Germanic epic. Heliand is the largest known work of written Old Saxon.

The poem would have been moderately popular since it has survived in only two manuscripts (Cotton MS. & Munich MS.) plus some further fragmentary versions in four other manuscripts.[1] It takes up about 6,000 lines. A praefatio exists, which could have been commissioned by either Louis the Pious (king from 814 to 840) or Louis the German (806–876). This praefatio was first printed by Matthias Flacius in 1562, and while it has no authority in the manuscripts it is generally deemed to be authentic.[2] The first mention of the poem itself in modern times occurred when Franciscus Junius (the younger) transcribed a fragment in 1587.[3] It was not printed until 1705, by the English clergyman George Hickes. The first modern edition of the poem was published in 1830 by Johann Andreas Schmeller.[4]

Historical context

[edit]The Heliand was probably written at the request of emperor Louis the Pious around AD 830 to combat Saxon ambivalence toward Christianity. The Saxons were forced to convert to Christianity in the late 8th to early 9th century after 33 years of conflict between the Saxons under Widukind and the Franks under Charlemagne.[5] Around the time that the Heliand was written, there was a revolt of the Saxon stelinga, or lower social castes. Murphy depicts the significant influence the Heliand had over the fate of European society; he writes that the author of the Heliand "created a unique cultural synthesis between Christianity and Germanic warrior society – a synthesis that would plant the seed that would one day blossom in the full-blown culture of knighthood and become the foundation of medieval Europe."[5]

Manuscripts

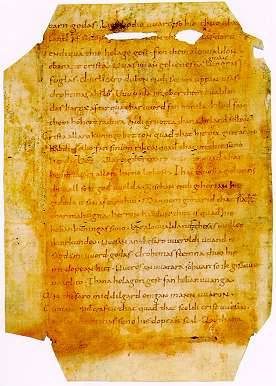

[edit]The 9th-century poem on the Gospel history, to which its first editor, J. A. Schmeller, gave the name of Heliand (the word used in the text for Savior, answering to the Old English hǣlend and the modern German and Dutch Heiland), is, with the fragments of a poem based on the Book of Genesis, all that remains of the poetical literature of the old Saxons, i.e. the Saxons who continued in their original home.[6] It contained when entire about 6000 lines, and portions of it are preserved in two nearly complete manuscripts and four fragments. The Cotton MS. in the British Library, written probably in the second half of the 10th century, is one of the nearly complete manuscripts, ending in the middle of the story of the journey to Emmaus. It is believed to have an organization closer to the original version because it is divided into fitts, or songs.[5] The Munich MS., formerly at Bamberg, begins at line 85, and has many lacunae, but continues the history down to the last verse of St. Luke's Gospel, ending, however, in the middle of a sentence with the last two fitts missing. This manuscript is now retained in Munich at the Bavarian State Library. Because it was produced on calf skin of high quality, it has been preserved in good condition.[5] Neumes above the text in this version reveal that the Heliand may have been sung. A fragment discovered at Prague in 1881 contains lines 958–1006, and another, in the Vatican Library, discovered by K. Zangemeister in 1894, contains lines 1279–1358.[6] Two additional fragments exist that were discovered most recently. The first was discovered in 1979 at a Jesuit High School in Straubing by B. Bischoff and is currently held in Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. It consists of nearly three leaves and contains 157 poetic lines.[7] The final fragment was found in Leipzig in 2006 by T. Doring and H. U. Schmid. This fragment consists of only one leaf that contains 47 lines of poetry, and it is currently kept at Bibliotheca Albertina.[7]

Authorship and relation to Old Saxon Genesis

[edit]The poem is based not directly on the New Testament, but on the pseudo-Tatian's Gospel harmony, and it demonstrates the author's acquaintance with the commentaries of Alcuin, Bede, and Rabanus Maurus.[6]

Early scholarship, notably that of Braune, hypothesized that the Heliand was authored by the same hand as the Old Saxon Genesis, but scholarly consensus has shifted away from this view; Sievers had already abandoned the hypothesis when Braune published his study.[8] Large parts of that poem are extant only in an Old English translation, known as Genesis B. The portions that have been preserved in the original language are contained in the same Vatican manuscript that includes the fragment of the Heliand referred to above. In the one language or the other, there are in existence the following three fragments: (I) The passage which appears as lines 235–851 of the Old English verse Genesis in the Caedmon Manuscript (MS Junius 11) (this fragment is known as Genesis B, distinguishing it from the rest of the poem, Genesis A), about the revolt of the angels and the temptation and fall of Adam and Eve. Of this a short part corresponding to lines 790–820 exists also in the original Old Saxon. (2) The story of Cain and Abel, in 124 lines. (3) The account of the destruction of Sodom, in 187 lines. The main source of the Genesis is the Bible, but Eduard Sievers showed that considerable use was made of two Latin poems by Alcimus Avitus, De initio mundi and De peccato originali.[6]

The two poems give evidence of genius and trained skill, though the poet was no doubt hampered by the necessity of not deviating too widely from the sacred.[citation needed] Within the limits imposed by the nature of his task, his treatment of his sources is remarkably free, the details unsuited for poetic handling being passed over, or, in some instances, boldly altered. In many passages his work gives the impression of being not so much an imitation of the ancient Germanic epic, as a genuine example of it, though concerned with the deeds of other heroes than those of Germanic tradition. In the Heliand, the Saviour and His Apostles are presented as a king and his faithful warriors. While some argue that the use of the traditional epic phrases appears to be not, as with Cynewulf or the author of Andreas, a mere following of accepted models but rather the spontaneous mode of expression of one accustomed to sing of heroic themes, others argue that the Heliand was intentionally and methodically composed after careful study of the formula of other German poems. The Genesis fragments have less of the heroic tone, except in the splendid passage describing the rebellion of Satan and his host. It is noteworthy that the poet, like John Milton, sees in Satan no mere personification of evil, but the fallen archangel, whose awful guilt could not obliterate all traces of his native majesty. Somewhat curiously, but very naturally, Enoch the son of Cain is confused with the Enoch who was translated to heaven – an error which the author of the Old English Genesis avoids, though (according to the existing text) he confounds the names of Enoch and Enos.[6]

Such external evidence as exists bearing on the origin of the Heliand and the companion poem is contained in a Latin document printed by Flacius Illyricus in 1562. This is in two parts; the one in prose, entitled (perhaps only by Flacius himself) Praefatio ad librum antiquum in lingua Saxonica conscriptum ; the other in verse, headed Versus de poeta et Interpreta hujus codicis. The Praefatio begins by stating that the emperor Ludwig the Pious, desirous that his subjects should possess the word of God in their own tongue, commanded a certain Saxon, who was esteemed among his countrymen as an eminent poet, to translate poetically into the German language the Old and New Testaments. The poet willingly obeyed, all the more because he had previously received a divine command to undertake the task. He rendered into verse all the most important parts of the Bible with admirable skill, dividing his work into vitteas, a term which, the writer says, may be rendered by lectiones or sententias. The Praefatio goes on to say that it was reported that the poet, till then knowing nothing of the art of poetry, had been admonished in a dream to turn into verse the precepts of the divine law, which he did with so much skill that his work surpasses in beauty all other German poetry (Ut cuncta Theudisca poemata suo vincat decore). The Versus practically reproduce in outline Bede's account of Caedmon's dream, without mentioning the dream, but describing the poet as a herdsman, and adding that his poems, beginning with the creation, relate the history of the five ages of the world down to the coming of Christ.[6]

Controversies

[edit]Authorship

[edit]The suspicion of some earlier scholars that the Praefatio and the Versus might be a modern forgery is refuted by the occurrence of the word vitteas, which is the Old Saxon fihtea, corresponding to the Old English fitt, which means a canto of a poem. It is impossible that a scholar of the 16th century could have been acquainted with this word,[citation needed] and internal evidence shows clearly that both the prose and the verse are of early origin. The Versus, considered in themselves, might very well be supposed to relate to Caedmon; but the mention of the five ages of the world in the concluding lines is obviously due to recollection of the opening of the Heliand (lines 46–47). It is therefore certain that the Versus, as well as the Praefatio, attribute to the author of the Heliand a poetic rendering of the Old Testament. Their testimony, if accepted, confirms the ascription to him of the Genesis fragments, which is further supported by the fact that they occur in the same MS. with a portion of the Heliand. As the Praefatio speaks of the emperor Ludwig in the present tense, the former part of it at least was probably written in his reign, i.e. not later than AD 840. The general opinion of scholars is that the latter part, which represents the poet as having received his vocation in a dream, is by a later hand, and that the sentences in the earlier part which refer to the dream are interpolations by this second author. The date of these additions, and of the Versus, is of no importance, as their statements are not credible.[9]

That the author of the Heliand was, so to speak, another Caedmon – an unlearned man who turned into poetry what was read to him from the sacred writings – is impossible according to some scholars, because in many passages the text of the sources is so closely followed that it is clear that the poet wrote with the Latin books before him.[10] Other historians, however, argue that the possibility that the author may have been illiterate should not be dismissed because the translations seem free compared to line-by-line translations that were made from Tatian's Diatessaron in the second quarter of the 9th century into Old High German. Additionally, the poem also shares much of its structure with Old English, Old Norse, and Old High German alliterative poetry which all included forms of heroic poetry that were available only orally and passed from singer to singer.[5] Repetitions of particular words and phrases as well as irregular beginnings of fits (sentences begin at the middle of a line rather than at the beginning of a line to help with alliteration) that occur in the Heliand seem awkward as written text but make sense when considering the Heliand formerly as a song for after-dinner singing in the mead hall or monastery.[5] There is no reason for rejecting the almost contemporary testimony of the first part of the Free folio that the author of the Heliand had won renown as a poet before he undertook his great task at the emperor's command. It is certainly not impossible that a Christian Saxon, sufficiently educated to read Latin easily, may have chosen to follow the calling of a scop or minstrel instead of entering the priesthood or the cloister; and if such a person existed, it would be natural that he should be selected by the emperor to execute his design. As has been said above, the tone of many portions of the Heliand is that of a man who was no mere imitator of the ancient epic, but who had himself been accustomed to sing of heroic themes.[10]

German Christianity

[edit]Scholars disagree over whether the overall tone of the Heliand lends to the text being an example of a Germanized Christianity or a Christianized Germany. Some historians believe that the German traditions of fighting and enmity are so well pronounced as well as an underlying message of how it is better to be meek than mighty that the text lends more to a Germanized Christianity. Other scholars argue that the message of meekness is so blatant that it renders the text as a stronger representation of a Christianized Germany.[5] This discussion is important because it reveals what culture was more pervasive to the other.

Use by Luther

[edit]Many historians agree that Martin Luther possessed a copy of the Heliand. Luther referenced the Heliand as an example to encourage translation of Gospels into the vernacular.[5] Additionally, Luther also favored wording presented in the Heliand to other versions of the Gospels. For example, many scholars believe that Luther favored the angel's greeting to Mary in the Heliand – "you are dear to your Lord" – because he disliked the notion of referring to a human as "full of grace."[5]

Extra-canonical origins

[edit]Contention exists over whether the Heliand is connected to the Gospel of Thomas. The Gospel of Thomas is a Judaic/Christian version of the Gospels found in 1956 that has been attributed the apostle Thomas. Quispel, a Dutch scholar, argues that the Heliand's author used a primitive Diatessaron, the Gospel harmony written in 160-175 by Tatian and thus has connections to the Gospel of Thomas by this association. Other scholars, such as Krogmann assert that the Heliand shares a poetic style of the Diatessaron but that the author may not actually have relied on this source and therefore the Heliand would have no association to the Gospel of Thomas.[5]

Sample passages

[edit]tho sagda he that her scoldi cumin en wiscuning

mari endi mahtig an thesan middelgard

bezton giburdies; quad that it scoldi wesan barn godes,

quad that he thesero weroldes waldan scoldi

gio te ewandaga, erdun endi himiles.

He quad that an them selbon daga, the ina salingna

an thesan middilgard modar gidrogi

so quad he that ostana en scoldi skinan

huit, sulic so wi her ne habdin er

undartuisc erda endi himil odar huerigin

ne sulic barn ne sulic bocan. (VII, 582-92)

Then he spoke and said there would come a wise king,

magnificent and mighty, to this middle realm;

he would be of the best birth; he said that he would be the Son of God,

he said that he would rule this world,

earth and sky, always and forevermore.

he said that on the same day on which the mother gave birth to the Blessed One

in this middle realm, in the East,

he said, there would shine forth a brilliant light in the sky,

one such as we never had before

between heaven and earth nor anywhere else,

never such a baby and never such a beacon.[11]

Editions and translations

[edit]Editions

[edit]The first complete edition of the Heliand was published by J. A. Schmeller in 1830; the second volume, containing the glossary and grammar, appeared in 1840. The standard edition is that of Eduard Sievers (1877), in which the texts of the Cotton and Munich manuscripts are printed side by side. It is not provided with a glossary, but contains an elaborate and most valuable analysis of the diction, synonymy and syntactical features of the poem.[10]

Other useful editions are those of Moritz Heyne (3rd ed., 1903), Otto Behaghel (1882) and Paul Piper (1897, containing also the Genesis fragments). The fragments of the Heliand and the Genesis contained in the Vatican MS. were edited in 1894 by Karl Zangemeister and Wilhelm Braune under the title Bruchstücke der altsächsischen Bibeldichtung.[10]

James E. Cathey wrote Heliand: Text and Commentary (2002) (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, ISBN 0-937058-64-5), which includes an edited version of the text in the original language, commentaries in English and a very useful grammar of Old Saxon along with an appended glossary defining all of the vocabulary found in this version.

Translations

[edit]- The Heliand: Translated from the Old Saxon, trans. by Mariana Scott, UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures, 52 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966), doi:10.5149/9781469658346_Scott

- The Heliand: The Saxon Gospel, trans. by G. Ronald Murphy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992)

- An Annotated English Translation of the Old Saxon Heliand: A Ninth-century Biblical Paraphrase in the Germanic Epic Style, trans. by Tonya Kim Dewey (Edwin Mellen Press, 2010), ISBN 0773414827

- In 2012, four translations of the Heliand were published (Uitgeverij TwentseWelle, now Uitgeverij Twentse Media) in four modern Saxon dialects: Tweants (tr. Anne van der Meiden and Dr. Harry Morshuis), Achterhoeks (Henk Krosenbrink and Henk Lettink), Gronings (Sies Woltjer) and Münsterlands (Hannes Demming), along with a critical edition of the Old Saxon text by Timothy Sodmann. In 2022 two translations were added, one in Stellingwerfs and one in Sallands.

Studies

[edit]Luther's Heliand: Resurrection of the Old Saxon Epic in Leipzig (2011) by Timothy Blaine Price is a self-published book detailing results of the author's personal research and travels. Perspectives on the Old Saxon Heliand (2010) edited by Valentine A. Pakis contains critical essays and commentaries. G. Ronald Murphy published The Saxon Saviour: The Germanic Transformation of the Gospel in the Ninth-Century Heliand (1989) (New York: Oxford University Press).

See also

[edit]- Germanic languages: A language family, the languages of which are spoken in northern and northwestern Europe, and in many places colonized since around 1500

- Germanic peoples: Collective name of a number of tribes and peoples, originating from northern Europe, several of which invaded the Roman Empire in the 5th and 6th centuries

- their Germanic mythology

- Germanic Christianity that came to dominate much of North-Western Europe in the second millennium, i.e. the Germans (in a wide sense), Anglo-Saxons and the Scandinavians

- Beowulf: A prominent epic poem that may have been written around the same time, in the closely related Old English language.

- Muspilli: A similar Biblical poem of debated meaning, written in Old High German.

References

[edit]- ^ Mierke 2008, pp. 31–37.

- ^ Mierke 2008, pp. 52–55.

- ^ Kees Dekker, 'Francis Junius (1591-1677): Copyist or Editor?', Anglo-Saxon England, 29 (2000), 279-96 (p. 289).

- ^ Mierke 2008, pp. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pakis 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Bradley 1911, p. 221.

- ^ a b Price 2011.

- ^ Doane 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Bradley 1911, pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b c d Bradley 1911, p. 222.

- ^ Murphy 1989, pp. 51–52.

Bibliography

[edit]- Belkin, Johanna; Meier, Jürgen (1975), Bibliographie zu Otfrid von Weißenburg und zur altsächsischen Bibeldichtung (Heliand und Genesis), Bibliographien zur deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters (in German), vol. 7, Berlin, ISBN 3-503-00765-2

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bradley, Henry (1911). "Heliand". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–222.

- Doane, Alger N. (1991), The Saxon Genesis: An Edition of the West Saxon 'Genesis B' and the Old Saxon Vatican 'Genesis', Madison, Wisconsin / London: University of Wisconsin, ISBN 9780299128005 (with Genesis B).

- Gantert, Klaus (1998), Akkommodation und eingeschriebener Kommentar. Untersuchungen zur Übertragungsstrategie des Helianddichters, ScriptOralia (in German), vol. 111, Tübingen, ISBN 3-8233-5421-3

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Gantert, Klaus (2003), "Heliand (Fragment P)", in Peter Jörg Becker; Eef Overgaauw (eds.), Aderlass und Seelentrost. Die Überlieferung deutscher Texte im Spiegel Berliner Handschriften und Inkunabeln (in German), Mainz, pp. 28–29

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Heusler, Andreas (1921), Der Heliand in Simrocks Übertragung und die Bruchstücke der altsächsischen Genesis (in German), Leipzig

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Mierke, Gesine (2008), Memoria als Kulturtransfer: Der altsächsische 'Heiland' zwischen Spätantike und Frühmittelalter (in German), Cologne: Böhlau, ISBN 978-3-412-20090-9.

- Murphy, G. Ronald (1989), The Saxon Savior, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195060423.

- Murphy, G. Ronald (1992), The Heliand: The Saxon Gospel, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195073754.

- Pakis, Valentine (2010), Perspectives on the Old Saxon Heliand, Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, ISBN 978-1933202495.

- Price, Timothy Blaine (2011), Luther's Heliand: Resurrection of the Old Saxon Epic in Leipzig, New York: Peter Lang, ISBN 9781433113949.

- Priebsch, Robert (1925), The Heliand Manuscript, Cotton Caligula A. VII, in the British Museum: A Study, Oxford

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Rauch, Irmengard (2006), "The Newly Found Leipzig Heliand Fragment", Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics and Semiotic Analysis, 11 (1): 1–17, ISSN 1087-5557.

- Sowinski, Bernhard (1985), Darstellungsstil und Sprachstil im Heliand, Kölner germanistische Studien (in German), vol. 21, Köln, ISBN 3-412-02485-6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Taeger, Burkhard (1985), Der Heliand: ausgewählte Abbildungen zur Überlieferung, Litterae (in German), vol. 103, Göppingen, ISBN 3-87452-605-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - fon Weringha, Juw (1965), Heliand und Diatesseron (in German), Assen, OCLC 67893651

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Zanni, Roland (1980), Heliand, Genesis und das Altenglische. Die altsächsische Stabreimdichtung im Spannungsfeld zwischen germanischer Oraltradition und altenglischer Bibelepik, Quellen und Forschungen zur Sprach- und Kulturgeschichte der germanischen Völker (in German), vol. Neue Folge 75, 200, Berlin, ISBN 3-11-008426-0

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link).

External links

[edit]- Literary Encyclopedia page

- Electronic facsimile of Eduard Siever's 1878 edition

- Concordances

- Searchable version

- On-going English translation

- Incomplete audio recording in Old Saxon

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XI (9th ed.). 1880. p. 630.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

Heliand

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Context

Commission and Composition Date

The Heliand was likely composed in the first half of the ninth century, during the reign of Louis the Pious (814–840 CE), following Charlemagne's conquest and forced Christianization of the Saxons in the late eighth century.[4][5] A prefatory prose text, known as the praefatio, asserts that an unnamed emperor—identified as Louis the Pious by its reference to "Ludouuicus piisimus Augustus"—commissioned the poem to further evangelize the Saxons through a vernacular adaptation of Christian teachings, emphasizing moral instruction over rote Latin liturgy.[6][4] This praefatio survives not in the primary Heliand manuscripts but was first published in 1562 by the Protestant scholar Matthias Flacius Illyricus from a now-lost source, prompting initial scholarly skepticism about its authenticity due to its absence from extant witnesses and potential sixteenth-century fabrication.[4] However, linguistic analysis aligns its Old Saxon features with the poem's dialect, and its historical context—post-Saxon pacification under Carolingian policy—supports ninth-century origins, leading most scholars to accept it as genuine.[6][4] Linguistic and paleographic evidence points to composition at the Benedictine monastery of Fulda, a key Carolingian center for Saxon missions, where the poem's dialect reflects East Franconian influences and thematic parallels exist with local biblical commentaries, such as those on Matthew dated after 822 CE.[3][7] Fulda's scriptorium, under abbots like Hrabanus Maurus, produced works blending classical metrics with vernacular elements, consistent with the Heliand's alliterative style adapted for missionary purposes.[8][3]Cultural and Missionary Background

The Saxon Wars, waged by Charlemagne from 772 to 804 CE, culminated in the subjugation of the pagan Saxons through military campaigns that included the destruction of sacred sites like the Irminsul pillar in 772 and mass executions, such as the 782 Verden massacre where approximately 4,500 Saxon rebels were killed for apostasy after prior baptisms.[9][10] Charlemagne's capitularies, including the 782 Capitulary for Saxony, mandated baptism under penalty of death, tying Christian profession to political submission and prohibiting pagan practices like cremation or oath-swearing on non-Christian symbols, which fostered widespread resentment among Saxons who viewed these impositions as cultural erasure rather than spiritual enlightenment.[9][11] Under Charlemagne's successor, Louis the Pious (r. 814–840 CE), this coercive framework shifted toward efforts at deeper assimilation, as forced baptisms alone failed to eradicate underlying tribal paganism or secure lasting fealty; adaptive evangelism emerged to recast Christian doctrine in terms resonant with Germanic warrior ethos, aligning concepts of loyalty to a divine drohtin (chieftain-lord) with Saxon hierarchical bonds between lords and retainers.[12] The Heliand, composed circa 830 CE likely at Louis's behest, exemplifies this strategy by harmonizing Gospel narratives into an epic framework that preserved scriptural events—such as Christ's miracles, teachings, and Passion—while framing them through heroic tribal paradigms, portraying Jesus as a steadfast chieftain summoning faithful thegns (disciples) to his hall rather than imposing alien rituals.[13][14] This approach prioritized causal integration over syncretism, embedding biblical fidelity into Saxon cosmology to foster voluntary adherence; evidence of its efficacy lies in the poem's dissemination across Saxon territories and its role in stabilizing Christian observance post-wars, as subsequent records show declining pagan revolts and the establishment of bishoprics like those in Münster and Paderborn by the mid-ninth century, without doctrinal compromise as confirmed by the Heliand's orthodox alignment with canonical harmonies like Tatian's Diatessaron.[15][16] By leveraging empirical cultural parallels—equating Christian salvation with heroic wyrd (fate) under a sovereign lord—the work mitigated resentment from Charlemagne's mandates, enabling a transition from coerced nominalism to internalized fealty grounded in unaltered Gospel causality.[17][18]Manuscripts and Textual History

Surviving Manuscripts

The Heliand is preserved in six extant manuscripts, all incomplete and dating from the mid-9th to the 10th century, with four consisting of fragments only.[3] The two most extensive copies provide the basis for textual reconstruction, supplemented by collation of variants across witnesses due to the absence of a single complete archetype.[3] The principal manuscripts are designated M (Munich) and C (Cotton). Manuscript M, located in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, comprises 75 surviving leaves from an originally larger codex missing at least six folios, and dates to the 9th century.[19] Manuscript C, British Library Cotton Caligula A. vii, originates from the early 10th century and likewise contains lacunae, though it preserves sections absent in M.[20][21] The fragmentary manuscripts include V (Vatican), held in the Vatican Library and containing portions of the text alongside a Genesis fragment; P (Prague); and S (Straubing).[19][22] These shorter witnesses, also from the 9th-10th centuries, offer additional textual variants but cover limited passages.[3]| Manuscript | Siglum | Repository | Date | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Munich | M | Bayerische Staatsbibliothek | 9th century | 75 leaves; lacunae of at least six folios[19] |

| Cotton | C | British Library (Cotton Caligula A. vii) | Early 10th century | Lacunae; supplements gaps in M[20][21] |

| Vatican | V | Vatican Library | 9th-10th century | Fragmentary; includes Genesis excerpt[22] |

| Prague | P | National Library, Prague | 9th-10th century | Fragmentary[19] |

| Straubing | S | (Formerly Straubing; now dispersed) | 9th-10th century | Fragmentary[19] |