Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The word thou (/ðaʊ/) is a second-person singular pronoun in English. It is now largely archaic, having been replaced in most contexts by the word you, although it remains in use in parts of Northern England and in Scots (/ðu:/). Thou is the nominative form; the oblique/objective form is thee (functioning as both accusative and dative); the possessive is thy (adjective) or thine (as an adjective before a vowel or as a possessive pronoun); and the reflexive is thyself. When thou is the grammatical subject of a finite verb in the indicative mood, the verb form typically ends in -(e)st (e.g., "thou goest", "thou do(e)st"), but in some cases just -t (e.g., "thou art"; "thou shalt").

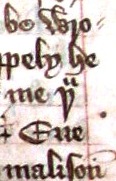

Originally, thou (in Old English: þū, pronounced [θuː]) was simply the singular counterpart to the plural pronoun ye, derived from an ancient Indo-European root. In Middle English, thou was sometimes represented with a scribal abbreviation that put a small "u" over the letter thorn: þͧ (later, in printing presses that lacked this letter, this abbreviation was sometimes rendered as yͧ). Starting in the 1300s, thou and thee were used to express familiarity, formality, or contempt, for addressing strangers, superiors, or inferiors, or in situations when indicating singularity to avoid confusion was needed; concurrently, the plural forms, ye and you, began to also be used for singular: typically for addressing rulers, superiors, equals, inferiors, parents, younger persons, and significant others.[3][clarification needed] In the 17th century, thou fell into disuse in the standard language, often regarded as impolite, but persisted, sometimes in an altered form, in regional dialects of England and Scotland,[4] as well as in the language of such religious groups as the Society of Friends. The use of the pronoun is also still present in Christian prayer and in poetry.[5]

Early English translations of the Bible used the familiar singular form of the second person, which mirrors common usage trends in other languages. The familiar and singular form is used when speaking to God in French (in Protestantism both in past and present, in Catholicism since the post–Vatican II reforms), German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Scottish Gaelic and many others (all of which maintain the use of an informal singular form of the second person in modern speech). In addition, the translators of the King James Version of the Bible attempted to maintain the distinction found in Biblical Hebrew, Aramaic and Koine Greek between singular and plural second-person pronouns and verb forms, so they used thou, thee, thy, and thine for singular, and ye, you, your, and yours for plural.

In standard Modern English, thou continues to be used in formal religious contexts, in wedding ceremonies ("I thee wed"), in literature that seeks to reproduce archaic language, and in certain fixed phrases such as "fare thee well". For this reason, many associate the pronoun with solemnity or formality.

Many dialects have compensated for the lack of a singular/plural distinction caused by the disappearance of thou and ye through the creation of new plural pronouns or pronominals, such as yinz, yous[6] and y'all or the colloquial you guys ("you lot" in England). Ye remains common in some parts of Ireland, but the examples just given vary regionally and are usually restricted to colloquial speech.

Grammar

[edit]Because thou has passed out of common use, its traditional forms are often confused by those imitating archaic speech.[7][citation needed]

Declension

[edit]The English personal pronouns have standardized declension according to the following table:[citation needed]

| Nominative | Oblique | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | I | me | my/mine[# 1] | mine |

| plural | we | us | our | ours | |

| 2nd person | singular informal | thou | thee | thy/thine[# 1] | thine |

| plural informal | ye (you)[# 2] | you | your | yours | |

| formal | |||||

| 3rd person | singular | he/she/it | him/her/it | his/her/his (it)[# 3] | his/hers/his[# 3] |

| plural | they | them | their | theirs | |

- ^ a b The genitives my, mine, thy, and thine are used as possessive adjectives before a noun, or as possessive pronouns without a noun. All four forms are used as possessive adjectives: mine and thine are used before nouns beginning in a vowel sound, or before nouns beginning in the letter h, which was usually silent (e.g. thine eyes and mine heart, which was pronounced as mine art) and my and thy before consonants (thy mother, my love). However, only mine and thine are used as possessive pronouns, as in it is thine and they were mine (not *they were my).

- ^ Ye had fallen out of use by c. 1600, being replaced by the original oblique you.

- ^ a b From the early Early Modern English period up until the 17th century, his was the possessive of the third-person neuter it as well as of the third-person masculine he. Genitive it appears once in the 1611 King James Bible (Leviticus 25:5) as groweth of it owne accord.

Conjugation

[edit]Verb forms used after thou generally end in -est (pronounced /ᵻst/) or -st in the indicative mood in both the present and the past tenses. These forms are used for both strong and weak verbs.

Typical examples of the standard present and past tense forms follow. The e in the ending is optional; early English spelling had not yet been standardized. In verse, the choice about whether to use the e often depended upon considerations of meter.

- to know: thou knowest, thou knewest

- to drive: thou drivest, thou drovest

- to make: thou makest, thou madest

- to love: thou lovest, thou lovedst

- to want: thou wantest, thou wantedst

Modal verbs also have -(e)st added to their forms:

- can: thou canst

- could: thou couldst

- may: thou mayest

- might: thou mightst

- should: thou shouldst

- would: thou wouldst

- ought to: thou oughtest to

A few verbs have irregular thou forms:

- to be: thou art (or thou beest), thou wast /wɒst/ (or subjunctive thou wert; originally thou were)

- to have: thou hast, thou hadst

- to do: thou dost /dʌst/ (or thou doest in non-auxiliary use) and thou didst

- shall: thou shalt

- will: thou wilt

A few others are not inflected:

- must: thou must

In Proto-English, the second-person singular verb inflection was -es. This came down unchanged[citation needed] from Indo-European and can be seen in quite distantly related Indo-European languages: Russian знаешь, znayesh, thou knowest; Latin amas, thou lovest. (This is parallel to the history of the third-person form, in Old English -eþ, Russian, знает, znayet, he knoweth, Latin amat he loveth.) The anomalous development[according to whom?] from -es to modern English -est, which took place separately at around the same time in the closely related German and West Frisian languages, is understood to be caused by an assimilation of the consonant of the pronoun, which often followed the verb. This is most readily observed in German: liebes du → liebstu → liebst du (lovest thou).[8]

There are some speakers of modern English[who?] that use thou/thee but use thee as the subject and conjugate the word with is/was, i.e. thee is, thee was, thee has, thee speaks, thee spoke, thee can, thee could. However this is not considered standard.[citation needed][clarification needed]

Comparison

[edit]| Early Modern English | Modern West Frisian | Modern German | Modern Dutch | Modern English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thou hast | Do hast [doː ˈhast] |

Du hast [duː ˈhast] |

Jij hebt [jɛi ˈɦɛpt] |

You have |

| She hath | Sy hat [sɛi ˈhat] |

Sie hat [ziː ˈhat] |

Zij heeft [zɛi ˈɦeːft] |

She has |

| What hast thou? | Wat hasto? [vat ˈhasto] |

Was hast du? [vas ˈhast duː] |

Wat heb je? [ʋɑt ˈɦɛp jə] |

What do you have? (What have you?) |

| What hath she? | Wat hat sy? [vat ˈhat sɛi] |

Was hat sie? [vas ˈhat ziː] |

Wat heeft zij? [ʋɑt ˈɦeːft sɛi] |

What does she have? (What has she?) |

| Thou goest | Do giest [doː ˈɡiəst] |

Du gehst [duː ˈɡeːst] |

Jij gaat [jɛi ˈɣaːt] |

You go |

| Thou doest | Do dochst [doː ˈdoχst] |

Du tust [duː ˈtuːst] |

Jij doet [jɛi ˈdut] |

You do |

| Thou art (variant thou beest) |

Do bist [doː ˈbɪst] |

Du bist [duː ˈbɪst] |

Jij bent [jɛi ˈbɛnt] |

You are |

In Dutch, the equivalent of "thou", du, also became archaic and fell out of use and was replaced by the Dutch equivalent of "you", gij (later jij or u), just as it has in English, with the place of the informal plural taken by jullie (compare English y’all).

In the subjunctive and imperative moods, the ending in -(e)st is dropped (although it is generally retained in thou wert, the second-person singular past subjunctive of the verb to be). The subjunctive forms are used when a statement is doubtful or contrary to fact; as such, they frequently occur after if and the poetic and.

- If thou be Johan, I tell it thee, right with a good advice ...;[9]

- Be Thou my vision, O Lord of my heart ...[10]

- I do wish thou wert a dog, that I might love thee something ...[11]

- And thou bring Alexander and his paramour before the Emperor, I'll be Actaeon ...[12]

- O WERT thou in the cauld blast, ... I'd shelter thee ...[13]

In modern regional English dialects that use thou or some variant, such as in Yorkshire and Lancashire, it often takes the third person form of the verb -s. This comes from a merging of Early Modern English second person singular ending -st and third person singular ending -s into -s (the latter a northern variation of -þ (-th)).

The present indicative form art ("þu eart") goes back to West Saxon Old English (see OED s.v. be IV.18) and eventually became standard, even in the south (e.g. in Shakespeare and the Bible). For its influence also from the North, cf. Icelandic þú ert. The preterite indicative of be is generally thou wast.[citation needed]

Etymology

[edit]Thou originates from Old English þū, and ultimately via Grimm's law from the Proto-Indo-European *tu, with the expected Germanic vowel lengthening in accented monosyllabic words with an open syllable. Thou is therefore cognate with Icelandic and Old Norse þú, German and Continental Scandinavian du, Latin and all major Romance languages, Irish, Kurdish, Lithuanian and Latvian tu or tú, Greek σύ (sy), Slavic ты / ty or ти / ti, Armenian դու (dow/du), Hindi तू (tū), Bengali: তুই (tui), Persian تُو (to) and Sanskrit त्वम् (tvam). A cognate form of this pronoun exists in almost every other Indo-European language.[14]

History

[edit]Old and Middle English

[edit]

In Old English, thou was governed by a simple rule: thou addressed one person, and ye more than one. Beginning in the 1300s thou was gradually replaced by the plural ye as the form of address for a superior person and later for an equal. For a long time, however, thou remained the most common form for addressing an inferior person.[3]

The practice of matching singular and plural forms with informal and formal connotations is called the T–V distinction and in English is largely due to the influence of French. This began with the practice of addressing kings and other aristocrats in the plural. Eventually, this was generalized, as in French, to address any social superior or stranger with a plural pronoun, which was felt to be more polite. In French, tu was eventually considered either intimate or condescending (and to a stranger, potentially insulting), while the plural form vous was reserved and formal.[citation needed]

General decline in Early Modern English

[edit]Fairly suddenly in the 17th century, thou began to decline in the standard language (that is, particularly in and around London), often regarded as impolite or ambiguous in terms of politeness. It persisted, sometimes in an altered form, particularly in regional dialects of England and Scotland farther from London,[4] as well as in the language of such religious groups as the Society of Friends. Reasons commonly maintained by modern linguists as to the decline of thou in the 17th century include the increasing identification of you with "polite society" and the uncertainty of using thou for inferiors versus you for superiors (with you being the safer default) amidst the rise of a new middle class.[15]

In the 18th century, Samuel Johnson, in A Grammar of the English Tongue, wrote: "in the language of ceremony ... the second person plural is used for the second person singular", implying that thou was still in everyday familiar use for the second-person singular, while you could be used for the same grammatical person, but only for formal contexts. However, Samuel Johnson himself was born and raised not in the south of England, but in the West Midlands (specifically, Lichfield, Staffordshire), where the usage of thou persists until the present day (see below), so it is not surprising that he would consider it entirely ordinary and describe it as such. By contrast, for most speakers of southern British English, thou had already fallen out of everyday use, even in familiar speech, by sometime around 1650.[16] Thou persisted in a number of religious, literary and regional contexts, and those pockets of continued use of the pronoun tended to undermine the obsolescence of the T–V distinction.

One notable consequence of the decline in use of the second person singular pronouns thou, thy, and thee is the obfuscation of certain sociocultural elements of Early Modern English texts, such as many character interactions in Shakespeare's plays, which were mostly written from 1589 to 1613. Although Shakespeare is far from consistent in his writings, his characters primarily tend to use thou (rather than you) when addressing another who is a social subordinate, a close friend or family member, or a hated wrongdoer.[17]

Usage

[edit]Use as a verb

[edit]Many European languages contain verbs meaning "to address with the informal pronoun", such as German duzen, French tutoyer, Spanish tutear and vosear, Swedish dua, Dutch jijen en jouen, Ukrainian тикати (tykaty), Russian тыкать (tykat'), Polish tykać, Romanian tutui, Hungarian tegezni, Finnish sinutella, etc. Additionally, the Norwegian noun dus refers to the practice of using this familiar form of address instead of the De/Dem/Deres formal forms in common use. Although uncommon in English, the usage did appear, such as at the trial of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1603, when Sir Edward Coke, prosecuting for the Crown, reportedly sought to insult Raleigh by saying,

- I thou thee, thou traitor![18]

- In modern English: I "thou" you, you traitor!

here using thou as a verb meaning to call (someone) "thou" or "thee". Although the practice never took root in Standard English, it occurs in dialectal speech in the north of England. A formerly common refrain in Yorkshire dialect for admonishing children who misused the familiar form was:

- Don't thee tha them as thas thee!

- In modern English: Don't you "tha" those who "tha" you!

- In other words: Don't use the familiar form "tha" towards those who refer to you as "tha". ("tha" being the local dialectal variant of "thou")

And similar in Lancashire dialect:

- Don't thee me, thee; I's you to thee!

- In standard English: Don't "thee" me, you! I'm "you" to you!

Religious uses

[edit]Christianity

[edit]Many conservative Christians use "Thee, Thou, Thy and Thine when addressing God" in prayer; in the Plymouth Brethren catechism Gathering Unto His Name, Norman Crawford explains the practice:[5]

The English language does contain reverential and respectful forms of the second person pronoun which allow us to show reverence in speaking to God. It has been a very long tradition that these reverential forms are used in prayer. In a day of irreverence, how good to display in every way that we can that "He (God) is not a man as I am" (Job 9:32).[5]

When referring to God, "thou" (as with other pronouns) is often capitalized, e.g. "For Thou hast delivered my soul from death" (Psalm 56:12–13).[19][20][21]

As William Tyndale translated the Bible into English in the early 16th century, he preserved the singular and plural distinctions that he found in his Hebrew and Greek originals. He used thou for the singular and ye for the plural regardless of the relative status of the speaker and the addressee. Tyndale's usage was standard for the period and mirrored that found in the earlier Wycliffe's Bible and the later King James Bible. But as the use of thou in non-dialect English began to decline in the 18th century,[22] its meaning nonetheless remained familiar from the widespread use of the latter translation.[23] The Revised Standard Version of the Bible, which first appeared in 1946, retained the pronoun thou exclusively to address God, using you in other places. This was done to preserve the tone, at once intimate and reverent, that would be familiar to those who knew the King James Version and read the Psalms and similar text in devotional use.[24] The New American Standard Bible (1971) made the same decision, but the revision of 1995 (New American Standard Bible, Updated edition) reversed it. Similarly, the 1989 Revised English Bible dropped all forms of thou that had appeared in the earlier New English Bible (1970). The New Revised Standard Version (1989) omits thou entirely and claims that it is incongruous and contrary to the original intent of the use of thou in Bible translation to adopt a distinctive pronoun to address the Deity.[25]

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which is still an authorized form of worship in the Church of England and much of the Anglican Communion, also uses the word thou to refer to the singular second person.[26][improper synthesis?]

Quakers traditionally used thee as an ordinary pronoun as part of their testimony of simplicity—a practice continued by certain Conservative Friends;[27] the stereotype has them saying thee for both nominative and accusative cases.[28] This was started at the beginning of the Quaker movement by George Fox, who called it "plain speaking", as an attempt to preserve the egalitarian familiarity associated with the pronoun. Most Quakers have abandoned this usage. At its beginning, the Quaker movement was particularly strong in the northwestern areas of England and particularly in the north Midlands area. The preservation of thee in Quaker speech may relate to this history.[29] Modern Quakers who choose to use this manner of "plain speaking" often use the "thee" form without any corresponding change in verb form, for example, is thee or was thee.[30]

In Latter-day Saint prayer tradition, the terms "thee" and "thou" are always and exclusively used to address God, as a mark of respect.[31]

Islam and Baháʼí Faith

[edit]In many of the Quranic translations, particularly those compiled by the Ahmadiyya, the terms thou and thee are used. One particular example is The Holy Quran - Arabic Text and English translation, translated by Maulvi Sher Ali.[32]

In the English translations of the scripture of the Baháʼí Faith, the terms thou and thee are also used. Shoghi Effendi, the head of the religion in the first half of the 20th century, adopted a style that was somewhat removed from everyday discourse when translating the texts from their original Arabic or Persian to capture some of the poetic and metaphorical nature of the text in the original languages and to convey the idea that the text was to be considered holy.[33]

Literary uses

[edit]Shakespeare

[edit]Like his contemporaries, William Shakespeare uses thou both in the intimate, French-style sense, and also to emphasize differences of rank, but he is by no means consistent in using the word, and friends and lovers sometimes call each other ye or you as often as they call each other thou,[34][35][36] sometimes in ways that can be analysed for meaning, but often apparently at random.

For example, in the following passage from Henry IV, Shakespeare has Falstaff use both forms with Henry. Initially using "you" in confusion on waking he then switches to a comfortable and intimate "thou".

- Prince: Thou art so fat-witted with drinking of old sack, and unbuttoning thee after supper, and sleeping upon benches after noon, that thou hast forgotten to demand that truly which thou wouldest truly know. What a devil hast thou to do with the time of the day? ...

- Falstaff: Indeed, you come near me now, Hal ... And, I prithee, sweet wag, when thou art a king, as God save thy Grace – Majesty, I should say; for grace thou wilt have none –

While in Hamlet, Shakespeare uses discordant second person pronouns to express Hamlet's antagonism towards his mother.

- Queen Gertrude: Hamlet, thou hast thy father much offended. [she means King Claudius, Hamlet's uncle and stepfather]

- Hamlet: Mother, you have my father much offended. [he means King Hamlet, his late father]

More recent uses

[edit]Except where everyday use survives in some regions of England,[37] the air of informal familiarity once suggested by the use of thou has disappeared; it is used often for the opposite effect with solemn ritual occasions, in readings from the King James Bible, in Shakespeare and in formal literary compositions that intentionally seek to echo these older styles. Since becoming obsolete in most dialects of spoken English, it has nevertheless been used by more recent writers to address exalted beings such as God,[38] a skylark,[39] Achilles,[40] and even The Mighty Thor.[41] In The Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader addresses the Emperor with the words: "What is thy bidding, my master?" In Leonard Cohen's song "Bird on the Wire", he promises his beloved that he will reform, saying "I will make it all up to thee." In Diana Ross's song, "Upside Down", (written by Chic's Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards) there is the lyric "Respectfully I say to thee I'm aware that you're cheatin'." In "Will You Be There", Michael Jackson sings, "Hold me / Like the River Jordan / And I will then say to thee / You are my friend." Notably, both Ross's and Jackson's lyrics combine thee with the usual form you.

The converse—the use of the second person singular ending -est for the third person—also occurs ("So sayest Thor!"―spoken by Thor). This usage often shows up in modern parody and pastiche[42] in an attempt to make speech appear either archaic or formal. The forms thou and thee are often transposed.

Current usage

[edit]You is now the standard English second-person pronoun and encompasses both the singular and plural senses. In some dialects, however, thou has persisted,[43] and in others thou is retained for poetic and/or literary use. It also survives as a fossil word in the commonly used phrase "holier-than-thou".[44]

Persistence of second-person singular

[edit]In traditional dialects, thou is used in the English counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, Staffordshire, Derbyshire, and some western parts of Nottinghamshire.[45] The Survey of Anglo-Welsh Dialects, which began in 1968,[46] found that thou persisted in scattered sites across Clwyd, Dyfed, Powys, and West Glamorgan.[47] Such dialects normally also preserve distinct verb forms for the singular second person: for example, thee coost (standard English: you could, archaic: thou couldst), in northern Staffordshire. Throughout rural Yorkshire, the old distinction between nominative and objective is preserved.[citation needed] The possessive is often written as thy in local dialect writings, but is pronounced as an unstressed tha, and the possessive pronoun has in modern usage almost exclusively followed other English dialects in becoming yours or the local[specify] word your'n (from your one):[citation needed]

| Nominative | Objective | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second person | singular | tha | thee | thy (tha) | yours / your'n |

The apparent incongruity between the archaic nominative, objective, and genitive forms of this pronoun on the one hand, and the modern possessive form on the other, may be a signal that the linguistic drift of Yorkshire dialect is causing tha to fall into disuse, although a measure of local pride in the dialect may be counteracting this.

Some other variants are specific to certain areas: In Sheffield, the initial consonant was pronounced as /d/, which led to the nickname of the "dee-dahs" for people from Sheffield.[48] In Lancashire and West Yorkshire, ta [tə] was used as an unstressed shortening of thou, which can be found in the song "On Ilkla Moor Baht 'at", although K.M. Petyt found this form to have been largely displaced from urban West Yorkshire in his 1970-1 fieldwork.[49]

In rural North Lancashire between Lancaster and the North Yorkshire border tha is preserved in colloquial phrases such as "What would tha like for thi tea?" (What would you like for your dinner), and "'appen tha waint" ("perhaps you won't" – happen being the dialect word for perhaps) and "tha knows" (you know). This usage in Lancashire is becoming rare, except for elderly and rural speakers.

A well-known routine by comedian Peter Kay, from Bolton, Greater Manchester (historically in Lancashire), features the phrase "Has tha nowt moist?”[50] (Have you got nothing moist?).

The use of the word "thee" in the song "I Predict a Riot" by Leeds band Kaiser Chiefs ("Watching the people get lairy / is not very pretty, I tell thee") caused some comment[51] by people who were unaware that the word is still in use in the Yorkshire dialect.

The word "thee" is also used in the song Upside Down "Respectfully, I say to thee / I'm aware that you're cheating".[52]

The use of the phrase "tha knows" has been widely used in various songs by Arctic Monkeys, a band from High Green, a suburb of Sheffield. Alex Turner, the band's lead singer, has also often replaced words with "tha knows" during live versions of the songs.[citation needed]

The use persists somewhat in the West Country dialects, albeit somewhat affected. Some of the Wurzels' songs include "Drink Up Thy Zider" and "Sniff Up Thy Snuff".[53]

Thoo has also been used in the Orcadian Scots dialect in place of the singular informal thou.[54] In Shetland dialect, the other form of Insular Scots, du and dee are used. The word "thou" has been reported in the North Northern Scots Cromarty dialect as being in common use in the first half of the 20th century and by the time of its extinction only in occasional use.[55]

Modern colloquial replacements

[edit]Many dialects have compensated for the lack of a singular/plural distinction caused by the disappearance of thou and ye through the creation of new plural pronouns or pronominals, such as yinz, yous[56] and y'all or the colloquial you guys ("you lot" in England). Ye remains common in some parts of Ireland, but the examples just given vary regionally and are usually restricted to colloquial speech.

Further, in other dialects the vacuum created by the loss of a distinction has led to the creation of new forms of the second-person plural, such as y'all in the Southern United States or yous by some Australians and heard in what are generally considered working class dialects in and near cities in the northeastern United States. The forms vary across the English-speaking world and between literature and the spoken language.[57]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "thou, thee, thine, thy (prons.)", Kenneth G. Wilson, The Columbia Guide to Standard American English. 1993. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Pressley, J. M. (8 January 2010). "Thou Pesky 'Thou'". Shakespeare Resource Centre.

- ^ a b "yǒu (pron.)". Middle English Dictionary. the Regents of the University of Michigan. 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b Shorrocks, 433–438.

- ^ a b c Crawford, Norman (1997). Gathering Unto His Name. GTP. pp. 178–179.

- ^ Kortmann, Bernd (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 1117. ISBN 978-3110175325.

- ^ "Archaic English Grammar -- dan.tobias.name". dan.tobias.name. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ Fennell, Barbara A. (2001). A history of English: a sociolinguistic approach. Blackwell Publishing. p. 22.

- ^ Middle English carol:

If thou be Johan, I tell it the

Ryght with a good aduyce

Thou may be glad Johan to be

It is a name of pryce.

- ^ Eleanor Hull, Be Thou My Vision, 1912 translation of traditional Irish hymn, Rob tu mo bhoile, a Comdi cride.

- ^ Shakespeare, Timon of Athens, act IV, scene 3.

- ^ Christopher Marlowe, Dr. Faustus, act IV, scene 2.

- ^ Robert Burns, O Wert Thou in the Cauld Blast(song), lines 1–4.

- ^ Entries for thou and *tu, in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

- ^ Nordquist, Richard (2016). "Notes on Second-Person Pronouns: Whatever Happened to 'Thou' and 'Thee'?" ThoughtCo. About, Inc.

- ^ Entry for thou in Merriam Webster's Dictionary of English Usage.

- ^ Atkins, Carl D. (ed.) (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Associated University Presses. p. 55.

- ^ Reported, among many other places, in H. L. Mencken, The American Language (1921), ch. 9, ss. 4., "The pronoun".

- ^ Shewan, Ed (2003). Applications of Grammar: Principles of Effective Communication. Liberty Press. p. 112. ISBN 1930367287.

- ^ Elwell, Celia (1996). Practical Legal Writing for Legal Assistants. Cengage Learning. p. 71. ISBN 0314061150.

- ^ The Teaching of Christ: A Catholic Catechism for Adults. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. 2004. p. 8. ISBN 1592760945.

- ^ Jespersen, Otto (1894). Progress in Language. New York: Macmillan. p. 260.

- ^ David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography. (Yale, 1995) ISBN 0-300-06880-8. See also David Daniell, The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. (Yale, 2003) ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

- ^ Preface to the Revised Standard Version Archived 2016-05-18 at the Wayback Machine 1971

- ^ "NRSV: To the Reader". Ncccusa.org. 2007-02-13. Archived from the original on 2010-02-06. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ^ The Book of Common Prayer. The Church of England. Retrieved on 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Q: What about the funny Quaker talk? Do you still do that?". Stillwater Monthly Meeting of Ohio Yearly Meeting of Friends. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ See, for example, The Quaker Widow by Bayard Taylor

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (1991). Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506905-6.

- ^ Maxfield, Ezra Kempton (1926). "Quaker 'Thee' and Its History". American Speech. 1 (12): 638–644. doi:10.2307/452011. JSTOR 452011.

- ^ Oaks, Dallin H. (May 1983). "The Language of Prayer". Ensign.

- ^ The Holy Quran, English Translation (PDF). Tilford, Surrey, UK: Islam International, Islamabad. 1989. ISBN 1-85372-314-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-26. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ^ Malouf, Diana (November 1984). "The Vision of Shoghi Effendi". Proceedings of the Association for Baháʼí Studies, Ninth Annual Conference. Ottawa, Canada. pp. 129–139.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cook, Hardy M.; et al. (1993). "You/Thou in Shakespeare's Work". SHAKSPER: The Global, Electronic Shakespeare Conference. Archived from the original on 2007-02-25. Retrieved 2004-12-04.

- ^ Calvo, Clara (1992). "'Too wise to woo peaceably': The Meanings of Thou in Shakespeare's Wooing-Scenes". In Maria Luisa Danobeitia (ed.). Actas del III Congreso internacional de la Sociedad española de estudios renacentistas ingleses (SEDERI) / Proceedings of the III International Conference of the Spanish Society for English Renaissance studies. Granada: SEDERI. pp. 49–59.

- ^ Gabriella, Mazzon (1992). "Shakespearean 'thou' and 'you' Revisited, or Socio-Affective Networks on Stage". In Carmela Nocera Avila; et al. (eds.). Early Modern English: Trends, Forms, and Texts. Fasano: Schena. pp. 121–36.

- ^ "Why Did We Stop Using 'Thou'?".

- ^ "Psalm 90". Archived from the original on August 13, 2004. Retrieved May 23, 2017. from the Revised Standard Version

- ^ Ode to a Skylark Archived 2009-01-04 at the Wayback Machine by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- ^ The Iliad, translated by E. H. Blakeney, 1921

- ^ "The Mighty Thor". Archived from the original on September 17, 2003. Retrieved May 23, 2017. 528

- ^ See, for example, Rob Liefeld, "Awaken the Thunder" (Marvel Comics, Avengers, vol. 2, issue 1, cover date Nov. 1996, part of the Heroes Reborn storyline.)

- ^ Evans, William (November 1969). "'You' and 'Thou' in Northern England". South Atlantic Bulletin. 34 (4). South Atlantic Modern Language Association: 17–21. doi:10.2307/3196963. JSTOR 3196963.

- ^ "Definition of HOLIER-THAN-THOU". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (21 January 2000). The Dialects of England. Wiley. p. 93. ISBN 978-0631218159.

- ^ Parry, David (1999). A Grammar and Glossary of the Conservative Anglo-Welsh Dialects of Rural Wales. The National Centre for English Cultural Tradition. p. Foreword.

- ^ Parry, David (1999). A Grammar and Glossary of the Conservative Anglo-Welsh Dialects of Rural Wales. The National Centre for English Cultural Tradition. p. 108.

- ^ Stoddart, Jana; Upton, Clive; Widdowson, J. D. A. (1999). "Sheffield dialect in the 1990s: revisiting the concept of NORMs". Urban Voices. London: Arnold. p. 79.

- ^ Petyt, Keith M. (1985). 'Dialect' and 'Accent' in Industrial West Yorkshire. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 375. ISBN 9027279497.

- ^ "Has tha nowt moist - Youtube". YouTube. 20 March 2012.

- ^ "BBC Top of the Pops web page". Bbc.co.uk. 2005-09-29. Archived from the original on 2010-06-18. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ^ "Nile Rodgers Official Website". Archived from the original on 2024-12-01. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ^ "Cider drinkers target core audience in Bristol". Bristol Evening Post. April 2, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-04-05. Retrieved April 2, 2010, and Wurzelmania. somersetmade ltd. Retrieved on 12 September 2007.

- ^ https://www.scotslanguage.com/articles/node/id/71

- ^ The Cromarty Fisherfolk Dialect Archived 2015-12-02 at the Wayback Machine, Am Baile, page 5

- ^ Kortmann, Bernd (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 1117. ISBN 978-3110175325.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. (June 1973). From Elfland to Poughkeepsie. Pendragon Press. ISBN 0-914010-00-X.

General and cited references

[edit]- Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language, 5th ed. ISBN 0-13-015166-1

- Burrow, J. A., Turville-Petre, Thorlac. A Book of Middle English. ISBN 0-631-19353-7

- Daniel, David. The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

- Shorrocks, Graham (1992). "Case Assignment in Simple and Coordinate Constructions in Present-Day English". American Speech. 67 (4): 432–444. doi:10.2307/455850. JSTOR 455850.

- Smith, Jeremy. A Historical Study of English: Form, Function, and Change. ISBN 0-415-13272-X

- "Thou, pers. pron., 2nd sing." Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (1989). Oxford English Dictionary Archived 2006-06-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- Trudgill, Peter. (1999) Blackwell Publishing. Dialects of England. ISBN 0-631-21815-7

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Roger and Gilman, Albert. The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity, 1960, reprinted in: Sociolinguistics: the Essential Readings, Wiley-Blackwell, 2003, ISBN 0-631-22717-2, 978-0-631-22717-5

- Byrne, St. Geraldine. Shakespeare's use of the pronoun of address: its significance in characterization and motivation, Catholic University of America, 1936 (reprinted Haskell House, 1970) OCLC 2560278.

- Quirk, Raymond. Shakespeare and the English Language, in Kenneth Muir and Sam Schoenbaum, eds, A New Companion to Shakespeare Studies*, 1971, Cambridge UP

- Wales, Katie. Personal Pronouns in Present-Day English. ISBN 0-521-47102-8

- Walker, Terry. Thou and you in early modern English dialogues: trials, depositions, and drama comedy, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2007, ISBN 90-272-5401-X, 9789027254016

External links

[edit]- A Grammar of the English Tongue by Samuel Johnson – includes description of 18th century use

- Contemporary use of thou in Yorkshire Archived 2007-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Thou: The Maven's Word of the Day

- You/Thou in Shakespeare's Work Archived 2007-02-25 at the Wayback Machine (archived forum discussion)

- A Note on Shakespeare's Grammar Archived 2007-05-23 at the Wayback Machine by Seamus Cooney

- The Language of Formal Prayer by Don E. Norton, Jr. - LDS

Grammar

Declension

In historical English, the second-person singular pronoun "thou" exhibited a case-based declension inherited from Old English but simplified over time, distinguishing it from the plural forms derived from "ye" and later "you." This system marked grammatical roles such as subject, object, and possession, reflecting influences from Proto-Germanic pronouns.[6] The nominative form "thou" served as the subject of a verb, as in the example "Thou art wise," emphasizing its role in Early Modern English texts like the King James Bible.[7] The accusative and dative forms both used "thee" for direct or indirect objects, such as "I give thee a gift"; in Old English, these cases were originally þē (accusative) and þē (dative), which merged in later usage.[6][7] For the genitive case indicating possession, "thy" functioned as the attributive adjective before consonants (e.g., "thy house"), while "thine" appeared as the predicative pronoun or before vowels and "h" (e.g., "the house is thine" or "thine honor"). These possessive forms evolved from Old English þīn, with "thine" retaining an absolute pronoun role similar to "mine."[7][6] Old English included archaic dual forms for the second person, addressing exactly two individuals and influenced by other Germanic languages like Old Norse; the nominative was "git" (you two), with accusative/dative "inc" and genitive "incer," but these were obsolete by Middle English.[8] The following table summarizes the declension paradigm for second-person pronouns in Early Modern English, contrasting singular and plural forms:| Case | Singular Nominative | Singular Objective (Acc./Dat.) | Singular Possessive Adjective | Singular Possessive Pronoun | Plural Nominative | Plural Objective (Acc./Dat.) | Plural Possessive Adjective | Plural Possessive Pronoun |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forms | thou | thee | thy | thine | ye (early), you (later) | you | your | yours |

Conjugation

In Early Modern English, verbs conjugated with "thou" as the subject in the second-person singular typically added the ending -est to the stem in the present indicative tense for regular verbs, as in "thou walkest" or "thou lovest," distinguishing it from the third-person singular -eth ending (e.g., "he walketh"). This -est suffix originated from Middle English developments and persisted in formal, literary, and religious texts through the 17th century.[9][10] For the irregular verb "to be," the second-person singular forms were "thou art" in the present tense and "thou wast" or "thou wert" in the past tense, with the subjunctive often using "thou be" or "thou were." Similarly, "to have" conjugated as "thou hast" in the present and "thou hadst" in the past.[11][12] Other common irregular verbs followed distinct patterns without the standard -est ending: "to do" became "thou dost" (present) and "thou didst" (past); "will" as "thou wilt"; and "shall" as "thou shalt." These forms, drawn from modal and auxiliary verbs, reflect phonetic and morphological irregularities preserved from Old English.[11][12] The following table illustrates conjugations for a regular verb ("love") and an irregular verb ("be") across persons in the present indicative tense, highlighting the distinct second-person singular forms with "thou":| Person | Regular: love (present) | Irregular: be (present) |

|---|---|---|

| I | love | am |

| Thou | lovest | art |

| He/She/It | loveth | is |

| We | love | are |

| Ye/You | love | are |

| They | love | are |