Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

History of Sirhind

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Sirhind is the older name of Fatehgarh Sahib, a city and Sikh pilgrimage site in Punjab, India. It is situated on the Delhi to Lahore Highway. It has a population of about 60,851. It is now a district headquarters in the state of Punjab; the name of the district is Fatehgarh Sahib.

Trigarta Kingdom

[edit]It derives its name probably from Sairindhas, a tribe that according to Varahamihira (AD 505-87), Brihat Samhita, once inhabited this part of the country. According to Hsuen Tsang, the Chinese traveller who visited India during the seventh century, Sirhind was the capital of the district of Shitotulo, or Shatadru (the River Sutlej), which was about 2000 H or 533 km in circuit. The Shatadru principality subsequently became part of the vast kingdom called Trigarta of which Jalandhar was the capital.

Medieval era

[edit]At the time of the struggle between the Hindu Shahis and the Ghaznavids, Sirhind was an important outpost on the eastern frontier of the Hindu Shahi Empire. With the contraction of their territory under the Ghaznavid onslaught, the Hindu Shahi capital was shifted in 1012 to Sirhind, where it remained till the death of Trilochanpala, the last ruling king of the dynasty. After the Hindu Shahi dynasty fell, the outpost of Sirhind was captured by the Ghaznavids, but it was later abandoned due to its distance from the Ghaznavid capital, Lahore. At the close of the 12th century, the town was occupied by the Chauhans. During the invasions of Muhammad Ghori, Sirhind, along with Bathinda, constituted the most important military outpost of Prithviraj Chauhan, the last Rajput ruler of Delhi. Muhammad Ghori captured the outpost of Bathinda and he then captured Sirhind and finally Delhi. Under the Mamluk dynasty, Sirhind constituted one of the six territorial divisions of the Punjab. In the time of Mughal Emperor Akbar, the rival towns of Sunam and Samana were subordinated to it and included in what was called Sirhind sarkar of the Subah of Delhi. It was refounded by Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq in 1361 AD at the behest of Sayyid Jalaluddin Bukhari, the spiritual guide of that king. The duty of building the town was given to Khwaja Fathallah, the brother of the ancestor of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi.[1] He made it a new pargana by dividing the old fief of Samana Firuz Shah dug a canal from the Sutlej.[incomprehensible] It was an important stronghold of the Delhi Sultanate. In 1415 Khizr Khan, the first Sayyid ruler of Delhi, nominated his son Mubarak Khan as a governor of Sirhind. In 1420, Khizr Khan defeated the insurgent Sarang Khan at Sirhind. In 1431, the city was invaded by the Khokhar tribe under their leader Mustafa Jasrath Khokhar. The town was however recaptured by Mubarak Shah in September 1432. In 1451 here, Bahlul Khan Lodi assumed the title of Sultan under the governorship of Malik Sultan Shah Lodi.

Mughal Empire

[edit]

Under the Mughals, Sirhind was the second largest city of the Punjab and the strongest fortified town between Delhi and Lahore. The town also enjoyed considerable commercial importance. According to Nasir Ali Sirhindi, Tankhi Nasin, Sirhind at that time possessed buildings which had no parallel in the whole of India. Spread over a distance of 3 kos (10 km approximately) on the banks of the River Hansala (now known as Sirhind Nala), it had many beautiful gardens and several canals. Mughal Emperor Jahangir, who made several visits to Sirhind, refers in his memoirs to the captivating beauty of its gardens. The jurisdiction of Sirhind sarkar extended to Anandpur which was the seat of Guru Gobind Singh in the closing decades of the seventeenth century. At the instance of one of the hill rulers, Raja Ajmer Chand, Wazir Khan, the faujdar of Sirhind, despatched some troops along with a couple of artillery pieces to reinforce the hill army attacking Anandpur. An inconclusive encounter took place on 13–14 October 1700.

On 22 June 1555, Humayun decisively defeated Sikandar Shah Suri at the Battle of Sirhind and reestablished the Mughal Empire. The city reached the zenith of its glory under the Mughal Empire in the 17th century. This city was a home of sixteenth-century saint Ahmad Sirhindi, popularly known as Mujadid Alif Sani which means 'Revivor of the Faith in the Second Millennium'. The mausoleum of this saint is still there. Under Mughal Emperor Akbar, it had turned the highest yielding sarkar. Under Sirhind sarkar there were 28 parganas. Due to its prosperity during the Mughal Empire it was known as Sirhind Bāvani which means Sirhind Fifty-two because it yielded a revenue of 52 lakh Rs, i.e. 5 million 200 thousand Rs per year. Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built a famous garden known as Aam Khas Bagh.

Guru Gobind Singh after a brief interval returned to Anandpur but had to quit it again on 5–6 December 1705 under pressure of a prolonged siege by the hill chief supported by Sirhind troops. Under the orders of the faujdar, Nawab Wazir Khan, Guru Gobind Singh's two younger sons, aged nine and seven, were cruelly bricked to death. They were enclosed alive in a wall in Sirhind and executed as the masonry rose up to their necks. Upon hearing the news of his sons' deaths, Guru Gobind Singh is reported to have prophesied the city of Sirhind being plundered, looted and devastated by his followers.[2][3]

Banda Singh Bahadur's rebellion

[edit]Mobilized under the leadership of Banda Singh Bahadur after the death of Guru Gobind Singh in November 1708, the Sikhs made a fierce attack upon Sirhind. The Mughal Army was routed and Wazir Khan killed in the Battle of Chappar Chiri fought on 12 May 1710. Sirhind was occupied by the Sikhs two days later, and Baj Singh was appointed governor. The city was plundered, razed and an immense loss of life and property occurred during Banda's siege.[4][5] The town was, however, taken again by the Mughal imperial forces. The Mughal Army recaptured Sirhind and they also captured Banda Singh Bahadur alive at Gurdas Nangal near Gurdaspur where they took him to Delhi and executed him for his rebellion.

Durrani Empire

[edit]In March 1748, Sirhind was seized, but only temporarily, by Ahmad Shah Durrani, the Afghan general of Nadir Shah who succeeded his master in the possession of the eastern part of his dominions. But Ahmad Shah Durrani was defeated by the Mughal rulers of Delhi who reoccupied the town, although the invader reconquered it during his fourth invasion during 1756-57. Early in 1758, the Sikhs, in collaboration with the Marathas, sacked Sirhind, and drove Prince Taimur, son of Ahmad Shah and his viceroy at Lahore, out of the Punjab.

Sirhind had been attacked by the Sikhs four times in the 18th century, the last being in 1764.[6] Ahmad Shah defeated the Marathas at Panipat in January 1761 and struck the Sikhs a severe blow in what is known as Vadda Ghalughara, the 'Great Massacre', that took place on 5 February 1762. Sikhs rallied and attacked Sirhind on 17 May 1762. defeating its faujdar, Zain Khan Sirhindi, who purchased peace by paying Rs 50,000 as a tribute to the Dal Khalsa. A more decisive battle took place on 14 January 1764 when Dal Khalsa. under Jassa Singh Ahluvalia, made another assault upon Sirhind. Zain Khan Sirhindi was killed in action and Sirhind was occupied and subjected to plunder and destruction. The booty was donated for the repair and reconstruction of the sacred shrines at Amritsar demolished by Ahmad Shah.

After the last attack known as the Battle of Sirhind in 13–14 January 1764, the cis-Sutlej tract became dominated by Sikhs after its Afghan governor, Zain Khan Sirhindi, was killed by a coalition of Sikh forces of both the Buddha Dal and Taruna Dal divisions of the Dal Khalsa military of the Sikh Confederacy.[6] The victory of the Sikhs ended foreign Afghan-rule over the region.[6] Lepel Henry Griffin stated:[6]

The storm burst at last. The Sikhs of the Majha country of Lahore, Amritsar, Ferozepur combined their forces at Sirhind, routed and killed the Afghan governor, Zain Khan and pouring across Sutlej occupied the whole country to the Jamna without further opposition. It is enough to say that with few exceptions, the leading families of today are the direct descendants of the conquerors of Zain Khan.

— Lepel Henry Griffin

Artillery, supplies, and treasures fell into the possession of the Sikh forces after the victory at Sirhind, which helped them further, especially Ala Singh of Patiala.[6] The victory helped consolidate the political entity of Patiala.[6] The settlement of Sirhind was mostly completely destroyed after the battle, which meant its former residents shifted to other locations, especially Patiala in Ala Singh's state.[6] Ala Singh would strike coins in the aftermath of the victory, with the coins bearing similarities to coins that had earlier been struck by Ahmad Shah Abdali at the Sirhind mint.[6] Control over Sirhind itself was handed-over to Bhai Buddha Singh, an aged man who was an associate of Guru Gobind Singh.[6] The sarkar of Sirhind was cut-up and distributed amongst hundreds of both petty and prominent Sikh sardars.[7]

Under Dal Khalsa

[edit]The booty was donated for the repair and reconstruction of the sacred shrines at Amritsar demolished by Ahmad Shah. The territories of the Sirhind sarkar were divided among the leaders of the Dal Khalsa, but no one was willing to take the town of Sirhind where Guru Gobind Singh's younger sons were subjected to a cruel fate. By a unanimous will it was made over to Buddha Singh, descendant of Bhai Bhagatu.[6]

Patiala State

[edit]

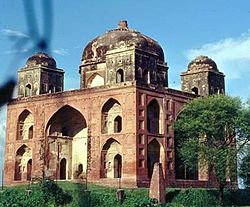

It was soon after (2 August 1764) transferred possession to Sardar Ala Singh, founder of the Patiala family. Sirhind thereafter remained part of the Patiala territory until the state lapsed in 1948. Maharaja Karam Singh of Patiala (1813–45) had gurdwaras constructed in Sirhind in memory of the young martyrs and their grandmother, Mata Gujari. He changed the name of the nizamat or district from Sirhind to Fatehgarh Sahib, after the name of the principal gurdwara. Besides the Sikh shrines, Sirhind has an important Muslim monument Rauza Sharif Mujjadid Alf Sani, the mausoleum of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1569-1624), the fundamentalist leader of the orthodox; Naqshbandi school of Sufism. There are a number of other tombs in the compound mostly of the members of Shaikh Ahmad's house.

References

[edit]- ^ Syed Yusuf Shahab (2021). Sirhind: A Monumental Example of Oblivion.

- ^ Bigelow, Anna (4 February 2010). Sharing the Sacred: Practicing Pluralism in Muslim North India. OUP USA. pp. 75, 271. ISBN 978-0-19-536823-9.

- ^ Singh, Ganda (1935). Life Of Banda Singh Bahadur. Punjabi University. p. 49.

And the alleged prophecy of Guru Gobind Singh, has, of late, been recently fulfilled, as a railway contractor 'appeared on the scene and carried the mass of old Sirhind as blast on which to lay the iron track'. And even to this day a pious Sikh, when travelling to the north or south of that city, may be seen pulling out a brick or two from its ruins and conveying them to the waters of the Sutlej or the Jamuna.

- ^ Dhavan, Purnima (3 November 2011). When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699-1799. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-975655-1.

- ^ History of the Sikhs: Evolution of Sikh Confederacies (1708-69) (PDF). Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Singh, Kirpal (2005). Baba Ala Singh: Founder of Patiala Kingdom (2nd ed.). Amritsar: Guru Nanak Dev University. pp. 77–82.

- ^ Banga, Indu (20 August 2023). Agrarian System of the Sikhs: Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century (Reprint ed.). Manohar Publishers and Distributors. pp. 68–69, 192–193. ISBN 9789388540193.

- Sirhind Town(Sahrind) The Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 23, p. 20.

- Sirhind Canal The Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 23, p. 18.

- Memories of a town known as Sirhind

History of Sirhind

View on GrokipediaSirhind, a strategically located town in Punjab along the historic Grand Trunk Road midway between Delhi and Lahore, functioned as the capital of the Mughal subah of Sirhind and developed into a major commercial and fortified center during the medieval period.[1] Its early references appear in the 6th-century Brihat Samhita of Varahamihira, associating the region with the Sairindhas tribe, and it later served as a military outpost under the Delhi Sultanate before flourishing under Mughal emperors like Babur and Akbar, who enhanced its infrastructure with gardens, mosques, and canals.[1] The town emerged as a hub of Sufism, notably as the birthplace in 1564 of Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi, a key Naqshbandi reformer whose teachings emphasized Islamic orthodoxy and spiritual revival, influencing Mughal religious policy.[2][3] Sirhind's historical trajectory shifted dramatically in the early 18th century amid Sikh-Mughal conflicts, particularly following the 1705 execution of Guru Gobind Singh's younger sons, Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh, ordered by the local governor Wazir Khan, an act that symbolized Mughal oppression in Sikh narratives and galvanized resistance.[1] This martyrdom prompted Banda Singh Bahadur's campaign, culminating in the 1710 Battle of Chappar Chiri, where Sikh forces defeated Wazir Khan, leading to the capture of Sirhind and the establishment of temporary Sikh governance; contrary to exaggerated accounts of total ruin, numerous Islamic monuments from before 1710 endured, with the city's decline attributed more to subsequent neglect and conflicts than to wholesale destruction.[1][4] The events cemented Sirhind's dual legacy as a site of spiritual prominence and pivotal confrontation, later commemorated through Sikh gurdwaras while its Mughal-era architecture reflects enduring cultural layers.[1]

.jpg/250px-Map_of_Sirhind_with_the_locations_of_Sikh_sites_labelled,_as_published_in_the_Mahan_Kosh_(1930).jpg)

.jpg/1329px-Map_of_Sirhind_with_the_locations_of_Sikh_sites_labelled,_as_published_in_the_Mahan_Kosh_(1930).jpg)