Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Partition of India

View on Wikipedia

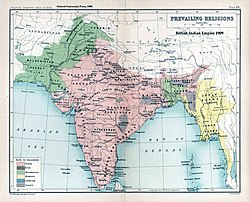

The prevailing religions of the British Indian Empire based on the Census of India, 1901 | |

| Date | August 1947 |

|---|---|

| Location | British India[a] |

| Outcome | Partition of British Indian Empire into independent dominions the Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan and refugee crises |

| Deaths | 200,000–2 million[1][b] |

| Displaced | 12–20 million displaced[2][c] |

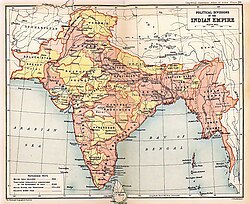

The partition of India in 1947 was the division of British India[a] into two independent dominion states, the Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan.[3] The Union of India is today the Republic of India, and the Dominion of Pakistan is the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People's Republic of Bangladesh. The partition involved the division of two provinces, Bengal and the Punjab, based on district-wise non-Muslim (mostly Hindu and Sikh) or Muslim majorities. It also involved the division of the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury, between the two new dominions. The partition was set forth in the Indian Independence Act 1947 and resulted in the dissolution of the British Raj, or Crown rule in India. The two self-governing countries of India and Pakistan legally came into existence at midnight on 14–15 August 1947.

The partition displaced between 12 and 20 million people along religious lines,[c] creating overwhelming refugee crises associated with the mass migration and population transfer that occurred across the newly constituted dominions; there was large-scale violence, with estimates of loss of life accompanying or preceding the partition disputed and varying between several hundred thousand and two million.[1][d] The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that plagues their relationship to the present.

The term partition of India does not cover the secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971, nor the earlier separations of Burma (now Myanmar) and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) from the administration of British India.[e] The term also does not cover the political integration of princely states into the two new dominions, nor the disputes of annexation or division arising in the princely states of Hyderabad, Junagadh, and Jammu and Kashmir, though violence along religious lines did break out in some princely states at the time of the partition. It does not cover the incorporation of the enclaves of French India into India during the period 1947–1954, nor the annexation of Goa and other districts of Portuguese India by India in 1961. Other contemporaneous political entities in the region in 1947, such as Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives, were unaffected by the partition.[f]

Background

[edit]Pre-World War II (1905–1938)

[edit]Partition of Bengal: 1905

[edit]-

1909 percentage of Hindus.

-

1909 percentage of Muslims.

-

1909 percentage of Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains.

In 1905, during his second term as viceroy of India, Lord Curzon divided the Bengal Presidency—the largest administrative subdivision in British India—into the Muslim-majority province of Eastern Bengal and Assam and the Hindu-majority province of Bengal (present-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Odisha).[7] Curzon's act, the partition of Bengal—which had been contemplated by various colonial administrations since the time of Lord William Bentinck, though never acted upon—was to transform nationalist politics as nothing else before it.[7]

The Hindu elite of Bengal, many of whom owned land that was leased out to Muslim peasants in East Bengal, protested strongly. The large Bengali-Hindu middle-class (the Bhadralok), upset at the prospect of Bengalis being outnumbered in the new Bengal province by Biharis and Oriyas, felt that Curzon's act was punishment for their political assertiveness.[7] The pervasive protests against Curzon's decision predominantly took the form of the Swadeshi ('buy Indian') campaign, involving a boycott of British goods. Sporadically, but flagrantly, the protesters also took to political violence, which involved attacks on civilians.[8] The violence was ineffective, as most planned attacks were either prevented by the British or failed.[9] The rallying cry for both types of protest was the slogan Bande Mataram (Bengali, lit. 'Hail to the Mother'), the title of a song by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, which invoked a mother goddess, who stood variously for Bengal, India, and the Hindu goddess Kali.[10] The unrest spread from Calcutta to the surrounding regions of Bengal when Calcutta's English-educated students returned home to their villages and towns.[11] The religious stirrings of the slogan and the political outrage over the partition were combined as young men, in such groups as Jugantar, took to bombing public buildings, staging armed robberies,[9] and assassinating British officials.[10] Since Calcutta was the imperial capital, both the outrage and the slogan soon became known nationally.[10]

The overwhelming, predominantly-Hindu protest against the partition of Bengal, along with the fear of reforms favouring the Hindu majority, led the Muslim elite of India in 1906 to the new viceroy Lord Minto, asking for separate electorates for Muslims. In conjunction, they demanded representation in proportion to their share of the total population, reflecting both their status as former rulers and their record of cooperating with the British. This would result[citation needed] in the founding of the All-India Muslim League in Dacca in December 1906. Although Curzon by now had returned to England following his resignation over a dispute with his military chief, Lord Kitchener, the League was in favor of his partition plan.[11] The Muslim elite's position, which was reflected in the League's position, had crystallized gradually over the previous three decades, beginning with the 1871 Census of British India,[citation needed] which had first estimated the populations in regions of Muslim majority.[12] For his part, Curzon's desire to court the Muslims of East Bengal had arisen from British anxieties ever since the 1871 census, and in light of the history of Muslims fighting them in the 1857 Rebellion and the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[citation needed]

In the three decades since the 1871 census, Muslim leaders across North India had intermittently experienced public animosity from some of the new Hindu political and social groups.[12] The Arya Samaj, for example, had not only supported the cow protection movement in their agitation,[13] but also—distraught at the census' Muslim numbers—organized "reconversion" events for the purpose of welcoming Muslims back to the Hindu fold.[12] In the United Provinces, Muslims became anxious in the late-19th century as Hindu political representation increased, and Hindus were politically mobilized in the Hindi–Urdu controversy and the anti-cow-killing riots of 1893.[14] In 1905, Muslim fears grew when Tilak and Lajpat Rai attempted to rise to leadership positions in the Congress, and the Congress itself rallied around the symbolism of Kali.[15] It was not lost on many Muslims, for example, that the bande mataram rallying cry had first appeared in the novel Anandmath in which Hindus had battled their Muslim oppressors.[15] Lastly, the Muslim elite, including Nawab of Dacca, Khwaja Salimullah, who hosted the League's first meeting in his mansion in Shahbag, were aware that a new province with a Muslim majority would directly benefit Muslims aspiring to political power.[15]

World War I, Lucknow Pact: 1914–1918

[edit]

World War I would prove to be a watershed in the imperial relationship between Britain and India. 1.4 million Indian and British soldiers of the British Indian Army would take part in the war, and their participation would have a wider cultural fallout: news of Indian soldiers fighting and dying with British soldiers, as well as soldiers from dominions like Canada and Australia, would travel to distant corners of the world both in newsprint and by the new medium of the radio.[16] India's international profile would thereby rise and would continue to rise during the 1920s.[16] It was to lead, among other things, to India, under its name, becoming a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920 and participating, under the name, "Les Indes Anglaises" (British India), in the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.[17] Back in India, especially among the leaders of the Indian National Congress, it would lead to calls for greater self-government for Indians.[16]

The 1916 Lucknow Session of the Congress was also the venue of an unanticipated mutual effort by the Congress and the Muslim League, the occasion for which was provided by the wartime partnership between Germany and Turkey. Since the Ottoman Sultan, also held guardianship of the Islamic holy sites of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, and, since the British and their allies were now in conflict with the Ottoman Empire, doubts began to increase among some Indian Muslims about the "religious neutrality" of the British, doubts that had already surfaced as a result of the reunification of Bengal in 1911, a decision that was seen as ill-disposed to Muslims.[18] In the Lucknow Pact, the League joined the Congress in the proposal for greater self-government that was campaigned for by Tilak and his supporters; in return, the Congress accepted separate electorates for Muslims in the provincial legislatures as well as the Imperial Legislative Council. In 1916, the Muslim League had anywhere between 500 and 800 members and did not yet have its wider following among Indian Muslims of later years; in the League itself, the pact did not have unanimous backing, having largely been negotiated by a group of "Young Party" Muslims from the United Provinces (UP), most prominently, the brothers Mohammad and Shaukat Ali, who had embraced the Pan-Islamic cause.[18] It gained the support of a young lawyer from Bombay, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who later rose to leadership roles in the League and the Indian independence movement. In later years, as the full ramifications of the pact unfolded, it was seen as benefiting the Muslim minority elites of provinces like UP and Bihar more than the Muslim majorities of Punjab and Bengal. At the time, the "Lucknow Pact" was an important milestone in nationalistic agitation and was seen so by the British.[18]

Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms: 1919

[edit]Secretary of State for India Montagu and Viceroy Lord Chelmsford presented a report in July 1918 after a long fact-finding trip through India the previous winter.[19] After more discussion by the government and parliament in Britain, and another tour by the Franchise and Functions Committee to identify who among the Indian population could vote in future elections, the Government of India Act of 1919 (also known as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms) was passed in December 1919.[19] The new Act enlarged both the provincial and Imperial legislative councils and repealed the Government of India's recourse to the "official majority" in unfavourable votes.[19] Although departments like defence, foreign affairs, criminal law, communications, and income-tax were retained by the viceroy and the central government in New Delhi, other departments like public health, education, land-revenue, local self-government were transferred to the provinces.[19] The provinces themselves were now to be administered under a new dyarchical system, whereby some areas like education, agriculture, infrastructure development, and local self-government became the preserve of Indian ministers and legislatures, and ultimately the Indian electorates, while others like irrigation, land-revenue, police, prisons, and control of media remained within the purview of the British governor and his executive council.[19] The new Act also made it easier for Indians to be admitted into the civil service and the army officer corps.

A greater number of Indians were now enfranchised, although, for voting at the national level, they constituted only 10% of the total adult male population, many of whom were still illiterate.[19] In the provincial legislatures, the British continued to exercise some control by setting aside seats for special interests they considered cooperative or useful. In particular, rural candidates, generally sympathetic to British rule and less confrontational, were assigned more seats than their urban counterparts.[19] Seats were also reserved for non-Brahmins, landowners, businessmen, and college graduates. The principle of "communal representation", an integral part of the Minto–Morley Reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and imperial legislative councils.[19] The Montagu–Chelmsford reforms offered Indians the most significant opportunity yet for exercising legislative power, especially at the provincial level, though restricted by the still limited number of eligible voters, by the small budgets available to provincial legislatures, and by the presence of rural and special interest seats that were seen as instruments of British control.[19]

Introduction of the two-nation theory: 1920s

[edit]The two-nation theory is the assertion, based on the former Indian Muslim ruling class' sense of being culturally and historically distinct, that Indian Hindus and Muslims are two distinct nations.[20][21][22] It argued that religion resulted in cultural and social differences between Muslims and Hindus.[23] While some professional Muslim Indian politicians used it to secure or safeguard a large share of political spoils for the Indian Muslims with the withdrawal of British rule, others believed the main political objective was the preservation of the cultural entity of Muslim India.[24] The two-nation theory was a founding principle of the Pakistan Movement (i.e., the ideology of Pakistan as a Muslim nation-state in South Asia), and the partition of India in 1947.[25]

Theodore Beck, who played a major role in founding of the All-India Muslim League in 1906, was supportive of two-nation theory. Another British official supportive of the theory includes Theodore Morison. Both Beck and Morison believed that parliamentary system of majority rule would be disadvantageous for the Muslims.[26]

Arya Samaj leader Lala Lajpat Rai laid out his own version of two-nation theory in 1924 to form "a clear partition of India into a Muslim India and a non-Muslim India". Lala believed in partition in response to the riots against Hindus in Kohat, North-West Frontier Province which diminished his faith in Hindu-Muslim unity.[26][27][28]

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar had initially proposed an embryonic form of the two-nation theory in his 1923 ideological pamphlet Essentials of Hindutva. The pamphlet served as the founding text of Hindutva, a Hindu nationalist ideology.[29] In 1937, during the 19th session of the Hindu Mahasabha in Ahmedabad, Savarkar declared, "India cannot be assumed today to be a unitarian and homogenous nation. On the contrary, there are two nations in the main: the Hindus and the Muslims, in India".[30] The theory is a source of inspiration to several Hindutva organisations, with causes as varied as the redefinition of Indian Muslims as non-Indian foreigners and second-class citizens in India, the expulsion of all Muslims from India, the establishment of a legally Hindu state in India, prohibition of conversions to Islam, and the promotion of conversions or reconversions of Indian Muslims to Hinduism.[31][32][33][34]

In 1940, Muhammad Ali Jinnah undertook the ideology that religion is the determining factor in defining the nationality of Indian Muslims. He termed it as the awakening of Muslims for the creation of Pakistan.[35] However, Jinnah opposed Partition of Punjab and Bengal and advocated for the integration of all of Punjab and Bengal into Pakistan without the displacement of any of its inhabitants, whether they were Sikhs or Hindus.[36] In 1943, Savarkar publicly expressed his support for Jinnah, stating, "I have no quarrel with Mr Jinnah’s two-nation theory. We, Hindus, are a nation by ourselves and it is a historical fact that Hindus and Muslims are two nations".[30]

There are varying interpretations of the two-nation theory, based on whether the two postulated nationalities can coexist in one territory or not, with radically different implications. One interpretation argued for sovereign autonomy, including the right to secede, for Muslim-majority areas of the Indian subcontinent, but without any transfer of populations (i.e., Hindus and Muslims would continue to live together). A different interpretation contends that Hindus and Muslims constitute "two distinct and frequently antagonistic ways of life and that therefore they cannot coexist in one nation."[37] In this version, a transfer of populations (i.e., the total removal of Hindus from Muslim-majority areas and the total removal of Muslims from Hindu-majority areas) was a desirable step towards a complete separation of two incompatible nations that "cannot coexist in a harmonious relationship."[38][39]

Opposition to the theory has come from two sources. The first is the concept of a single Indian nation, of which Hindus and Muslims are two intertwined communities.[40] This is a founding principle of the modern, officially secular Republic of India. Even after the formation of Pakistan, debates on whether Muslims and Hindus are distinct nationalities or not continued in that country as well.[41] The second source of opposition is the concept that while Indians are not one nation, neither are the Muslims or Hindus of the subcontinent, and it is instead the relatively homogeneous provincial units of the subcontinent which are true nations and deserving of sovereignty; the Baloch have presented this view,[42] along with the Sindhi[43] and Pashtun[44] sub-nationalities of Pakistan and the Assamese[45] and Punjabi[46] sub-nationalities of India.

Muslim homeland, provincial elections: 1930–1938

[edit]

In 1933, Choudhry Rahmat Ali had produced a pamphlet, entitled Now or Never, in which the term Pakistan, 'land of the pure', comprising the Punjab, North West Frontier Province (Afghania), Kashmir, Sindh, and Balochistan, was coined for the first time.[47] It did not attract political attention and,[47] a little later, a Muslim delegation to the Parliamentary Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms gave short shrift to the idea of Pakistan, calling it "chimerical and impracticable".[47]

In 1932, British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald accepted Ambedkar's demand for the "Depressed Classes" to have separate representation in the central and provincial legislatures. The Muslim League favoured this "communal award" as it had the potential to weaken the Hindu caste leadership. Mahatma Gandhi, who was seen as a leading advocate for Dalit rights, went on a fast to persuade the British to repeal these separate electorates. Ambedkar had to back down when it seemed Gandhi's life was threatened.[48][better source needed]

Two years later, the Government of India Act 1935 introduced provincial autonomy, increasing the number of voters in India to 35 million.[49] More significantly, law and order issues were for the first time devolved from British authority to provincial governments headed by Indians.[49] This increased Muslim anxieties about eventual Hindu domination.[49] In the 1937 Indian provincial elections, the Muslim League turned out its best performance in Muslim-minority provinces such as the United Provinces, where it won 29 of the 64 reserved Muslim seats.[49] In the Muslim-majority regions of the Punjab and Bengal regional parties outperformed the League.[49] In Punjab, the Unionist Party of Sikandar Hayat Khan, won the elections and formed a government, with the support of the Indian National Congress and the Shiromani Akali Dal, which lasted five years.[49] In Bengal, the League had to share power in a coalition headed by A. K. Fazlul Huq, the leader of the Krishak Praja Party.[49]

The Congress, on the other hand, with 716 wins in the total of 1585 provincial assemblies seats, was able to form governments in 7 out of the 11 provinces of British India.[49] In its manifesto, Congress maintained that religious issues were of lesser importance to the masses than economic and social issues. The election revealed that it had contested just 58 out of the total 482 Muslim seats, and of these, it won in only 26.[49] In UP, where the Congress won, it offered to share power with the League on condition that the League stops functioning as a representative only of Muslims, which the League refused.[49] This proved to be a mistake as it alienated Congress further from the Muslim masses. Besides, the new UP provincial administration promulgated cow protection and the use of Hindi.[49] The Muslim elite in UP was further alienated, when they saw chaotic scenes of the new Congress Raj, in which rural people who sometimes turned up in large numbers in government buildings, were indistinguishable from the administrators and the law enforcement personnel.[50]

The Muslim League conducted its investigation into the conditions of Muslims under Congress-governed provinces.[51] The findings of such investigations increased fear among the Muslim masses of future Hindu domination.[51] The view that Muslims would be unfairly treated in an independent India dominated by the Congress was now a part of the public discourse of Muslims.[51]

During and post-World War II (1939–1947)

[edit]

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Lord Linlithgow, Viceroy of India, declared war on India's behalf without consulting Indian leaders, leading the Congress provincial ministries to resign in protest.[51] By contrast the Muslim League, which functioned under state patronage,[52] organized "Deliverance Day" celebrations (from Congress dominance) and supported Britain in the war effort.[51] When Linlithgow met with nationalist leaders, he gave the same status to Jinnah as he did to Gandhi, and, a month later, described the Congress as a "Hindu organization".[52]

In March 1940, in the League's annual three-day session in Lahore, Jinnah gave a two-hour speech in English, in which were laid out the arguments of the two-nation theory, stating, in the words of historians Talbot and Singh, that "Muslims and Hindus...were irreconcilably opposed monolithic religious communities and as such, no settlement could be imposed that did not satisfy the aspirations of the former."[51] On the last day of its session, the League passed what came to be known as the Lahore Resolution, sometimes also "Pakistan Resolution",[51] demanding that "the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in the majority as in the north-western and eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute independent states in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign." Though it had been founded more than three decades earlier, the League would gather support among South Asian Muslims only during the Second World War.[53]

August Offer, Cripps Mission: 1940–1942

[edit]In August 1940, Lord Linlithgow proposed that India be granted dominion status after the war. Having not taken the Pakistan idea seriously, Linlithgow supposed that what Jinnah wanted was a non-federal arrangement without Hindu domination. To allay Muslim fears of Hindu domination, the "August Offer" was accompanied by the promise that a future constitution would consider the views of minorities.[54] Neither the Congress nor the Muslim League were satisfied with the offer, and both rejected it in September. The Congress once again started a program of civil disobedience.[55]

In March 1942, with the Japanese fast moving up the Malayan Peninsula after the Fall of Singapore,[52] and with the Americans supporting independence for India,[56] Winston Churchill, then Britain's prime minister, sent Sir Stafford Cripps, leader of the House of Commons, with an offer of dominion status to India at the end of the war in return for the Congress's support for the war effort.[57] Not wishing to lose the support of the allies they had already secured—the Muslim League, Unionists of Punjab, and the princes—Cripps's offer included a clause stating that no part of the British Indian Empire would be forced to join the post-war dominion. The League rejected the offer, seeing this clause as insufficient in meeting the principle of Pakistan.[58] As a result of that proviso, the proposals were also rejected by the Congress, which, since its founding as a polite group of lawyers in 1885,[59] saw itself as the representative of all Indians of all faiths.[57] After the arrival in 1920 of Gandhi, the pre-eminent strategist of Indian nationalism,[60] the Congress had been transformed into a mass nationalist movement of millions.[59]

Quit India Resolution: August 1942

[edit]In August 1942, Congress launched the Quit India Resolution, asking for drastic constitutional changes which the British saw as the most serious threat to their rule since the Indian rebellion of 1857.[57] With their resources and attention already spread thin by a global war, the nervous British immediately jailed the Congress leaders and kept them in jail until August 1945,[61] whereas the Muslim League was now free for the next three years to spread its message.[52] Consequently, the Muslim League's ranks surged during the war, with Jinnah himself admitting, "The war which nobody welcomed proved to be a blessing in disguise."[62] Although there were other important national Muslim politicians such as Congress leader Abul Kalam Azad, and influential regional Muslim politicians such as A. K. Fazlul Huq of the leftist Krishak Praja Party in Bengal, Sikander Hyat Khan of the landlord-dominated Punjab Unionist Party, and Abd al-Ghaffar Khan of the pro-Congress Khudai Khidmatgar (popularly, "red shirts") in the North West Frontier Province, the British were to increasingly see the League as the main representative of Muslim India.[63] The Muslim League's demand for Pakistan pitted it against the British and Congress.[64]

Labour victory in the UK election, decision to decolonize: 1945

[edit]The 1945 United Kingdom general election was won by the Labour Party. A government headed by Clement Attlee, with Stafford Cripps and Lord Pethick-Lawrence in the Cabinet, was sworn in. Many in the new government, including Attlee, had a long history of supporting the decolonization of India. The government's exchequer had been exhausted by the Second World War and the British public did not appear to be enthusiastic about costly distant involvements.[65][66] Late in 1945, the British government decided to end British Raj in India, and in early 1947 Britain announced its intention of transferring power no later than June 1948.[67] Attlee wrote later in a memoir that he moved quickly to restart the self-rule process because he expected colonial rule in Asia to meet renewed opposition after the war from both nationalist movements and the United States,[68] while his exchequer feared that post-war Britain could no longer afford to garrison an expansive empire.[65][66]

Indian provincial elections: 1946

[edit]Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee had been deeply interested in Indian independence since the 1920s, being surrounded by Labour statesmen who were affiliated with Krishna Menon and the India League, and for years had supported it. He now took charge of the government position and gave the issue the highest priority.[citation needed] A Cabinet Mission was sent to India led by the Secretary of State for India, Lord Pethick Lawrence, which also included Sir Stafford Cripps, who had visited India four years before. The objective of the mission was to arrange for an orderly transfer to independence.[69] In February 1946, mutinies broke out in the armed services, starting with RAF servicemen frustrated with their slow repatriation to Britain.[69] These mutinies failed to turn into revolutions as the mutineers surrendered after the Congress and the Muslim League convinced the mutineers that they won't get victimised.[70]

In early 1946, new elections were held in India.[71] This coincided with the infamous trial of three senior officers—Shah Nawaz Khan, Prem Sahgal, and Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon—of Subhas Chandra Bose's defeated Indian National Army (INA) who stood accused of treason. Now as the trials began, the Congress leadership, although having never supported the INA, chose to defend the accused officers and successfully rescued the INA members.[72][73]

British rule had lost its legitimacy for most Hindus, and conclusive proof of this came in the form of the 1946 elections with the Congress winning 91 percent of the vote among non-Muslim constituencies, thereby gaining a majority in the Central Legislature and forming governments in eight provinces, and becoming the legitimate successor to the British government for most Hindus. If the British intended to stay in India the acquiescence of politically active Indians to British rule would have been in doubt after these election results, although many rural Indians may still have acquiesced to British rule at this time.[74] The Muslim League won the majority of the Muslim vote as well as most reserved Muslim seats in the provincial assemblies, and it also secured all the Muslim seats in the Central Assembly.

-

Members of the 1946 Cabinet Mission to India meeting Muhammad Ali Jinnah. On the extreme left is Lord Pethick Lawrence; on the extreme right, Sir Stafford Cripps.

-

An aged and abandoned Muslim couple and their grandchildren are sitting by the roadside on this arduous journey. "The old man is dying of exhaustion. The caravan has gone on," wrote Bourke-White.

-

An elderly Sikh man is carrying his wife. Over 10 million people were uprooted from their homeland and traveled on foot, bullock carts and trains to their promised new home.

-

Gandhi in Bela, Bihar, after attacks on Muslims, 28 March 1947.

Cabinet Mission: July 1946

[edit]Recovering from its performance in the 1937 elections, the Muslim League was finally able to make good on the claim that it and Jinnah alone represented India's Muslims[75] and Jinnah quickly interpreted this vote as a popular demand for a separate homeland.[76] Tensions heightened while the Muslim League was unable to form ministries outside the two provinces of Sind and Bengal, with the Congress forming a ministry in the NWFP and the key Punjab province coming under a coalition ministry of the Congress, Sikhs and Unionists.[77]

The British, while not approving of a separate Muslim homeland, appreciated the simplicity of a single voice to speak on behalf of India's Muslims.[78] Britain had wanted India and its army to remain united to keep India in its system of 'imperial defense'.[79][80] With India's two political parties unable to agree, Britain devised the Cabinet Mission Plan. Through this mission, Britain hoped to preserve the united India which they and the Congress desired, while concurrently securing the essence of Jinnah's demand for a Pakistan through 'groupings.'[81] The Cabinet Mission scheme encapsulated a federal arrangement consisting of three groups of provinces. Two of these groupings would consist of predominantly Muslim provinces, while the third grouping would be made up of the predominantly Hindu regions. The provinces would be autonomous, but the centre would retain control over the defence, foreign affairs, and communications. Though the proposals did not offer independent Pakistan, the Muslim League accepted the proposals. Even though the unity of India would have been preserved, the Congress leaders, especially Nehru, believed it would leave the Center weak. On 10 July 1946, Nehru gave a "provocative speech," rejected the idea of grouping the provinces and "effectively torpedoed" both the Cabinet Mission Plan and the prospect of a United India.[82]

Direct Action Day: August 1946

[edit]After the Cabinet Mission broke down, in July 1946, Jinnah held a press conference at his home in Bombay. He proclaimed that the Muslim League was "preparing to launch a struggle" and that they "have chalked out a plan". He said that if the Muslims were not granted a separate Pakistan then they would launch "direct action". When asked to be specific, Jinnah retorted: "Go to the Congress and ask them their plans. When they take you into their confidence I will take you into mine. Why do you expect me alone to sit with folded hands? I also am going to make trouble."[83]

The next day, Jinnah announced 16 August 1946 would be "Direct Action Day" and warned Congress, "We do not want war. If you want war we accept your offer unhesitatingly. We will either have a divided India or a destroyed India."[83]

On that morning, armed Muslim gangs gathered at the Ochterlony Monument in Calcutta to hear Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the League's Chief Minister of Bengal, who, in the words of historian Yasmin Khan, "if he did not explicitly incite violence certainly gave the crowd the impression that they could act with impunity, that neither the police nor the military would be called out and that the ministry would turn a blind eye to any action they unleashed in the city."[84] That very evening, in Calcutta, Hindus were attacked by returning Muslim celebrants, who carried pamphlets distributed earlier which showed a clear connection between violence and the demand for Pakistan, and directly implicated the celebration of Direct Action Day with the outbreak of the cycle of violence that would later be called the "Great Calcutta Killing of August 1946".[85] The next day, Hindus struck back, and the violence continued for three days in which approximately 4,000 people died (according to official accounts), both Hindus and Muslims. Although India had outbreaks of religious violence between Hindus and Muslims before, the Calcutta killings were the first to display elements of "ethnic cleansing".[86] Violence was not confined to the public sphere, but homes were entered and destroyed, and women and children were attacked.[87] Although the Government of India and the Congress were both shaken by the course of events, in September, a Congress-led interim government was installed, with Jawaharlal Nehru as united India's prime minister.

The communal violence spread to Bihar (where Hindus attacked Muslims), to Noakhali in Bengal (where Muslims targeted Hindus), to Garhmukteshwar in the United Provinces (where Hindus attacked Muslims), and on to Rawalpindi in March 1947 in which Hindus and Sikhs were attacked or driven out by Muslims.[88]

Plan for partition: 1946–1947

[edit]In London, the president of the India League, V. K. Krishna Menon, nominated Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma as the only suitable viceregal candidate in clandestine meetings with Sir Stafford Cripps and Clement Attlee.[89] Prime Minister Attlee subsequently appointed Lord Louis Mountbatten as India's last viceroy, giving him the task to oversee British India's independence by 30 June 1948, with the instruction to avoid partition and preserve a united India, but with adaptable authority to ensure a British withdrawal with minimal setbacks. Mountbatten hoped to revive the Cabinet Mission scheme for a federal arrangement for India. But despite his initial keenness for preserving the centre, the tense communal situation caused him to conclude that partition had become necessary for a quicker transfer of power.[90][91][92][93]

Proposal of the Indian Independence Act

[edit]When Lord Mountbatten formally proposed the plan on 3 June 1947, Patel gave his approval and lobbied Nehru and other Congress leaders to accept the proposal. Knowing Gandhi's deep anguish regarding proposals of partition, Patel engaged him in private meetings discussions over the perceived practical unworkability of any Congress-League coalition, the rising violence, and the threat of civil war. At the All India Congress Committee meeting called to vote on the proposal, Patel said:[94]

I fully appreciate the fears of our brothers from [the Muslim-majority areas]. Nobody likes the division of India, and my heart is heavy. But the choice is between one division and many divisions. We must face facts. We cannot give way to emotionalism and sentimentality. The Working Committee has not acted out of fear. But I am afraid of one thing, that all our toil and hard work of these many years might go waste or prove unfruitful. My nine months in office have completely disillusioned me regarding the supposed merits of the Cabinet Mission Plan. Except for a few honourable exceptions, Muslim officials from the top down to the chaprasis (peons or servants) are working for the League. The communal veto given to the League in the Mission Plan would have blocked India's progress at every stage. Whether we like it or not, de facto Pakistan already exists in the Punjab and Bengal. Under the circumstances, I would prefer a de jure Pakistan, which may make the League more responsible. Freedom is coming. We have 75 to 80 percent of India, which we can make strong with our genius. The League can develop the rest of the country.

Following Gandhi's denial[95] and Congress' approval of the plan, Patel, Rajendra Prasad, C. Rajagopalachari represented Congress on the Partition Council, with Jinnah, Liaqat Ali Khan and Abdur Rab Nishtar representing the Muslim League. Late in 1946, the Labour government in Britain, its exchequer exhausted by the recently concluded World War II, decided to end British rule of India, with power being transferred no later than June 1948. With the British army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, advanced the date, allowing less than six months for a mutually agreed plan for independence.

Radcliffe Line

[edit]

In June 1947, the nationalist leaders, including Nehru, Valllabh Bhai Patel and J B Kripalini on behalf of the Congress, Jinnah, Liaqat Ali Khan, and Abdul Rab Nishtar representing the Muslim League, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs, agreed to a partition of the country in stark opposition to Gandhi's opposition to partition. The predominantly Hindu and Sikh areas were assigned to the new India and predominantly Muslim areas to the new nation of Pakistan; the plan included a partition of the Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal. The communal violence that accompanied the publication of the Radcliffe Line, the line of partition, was even more horrific. Describing the violence that accompanied the partition of India, historians Ian Talbot and Gurharpal Singh wrote:

There are numerous eyewitness accounts of the maiming and mutilation of victims. The catalogue of horrors includes the disemboweling of pregnant women, the slamming of babies' heads against brick walls, the cutting off of the victim's limbs and genitalia, and the displaying of heads and corpses. While previous communal riots had been deadly, the scale and level of brutality during the Partition massacres were unprecedented. Although some scholars question the use of the term 'genocide' concerning the partition massacres, much of the violence was manifested with genocidal tendencies. It was designed to cleanse an existing generation and prevent its future reproduction."[96]

Independence: August 1947

[edit]

Mountbatten administered the independence oath to Jinnah on the 14th, before leaving for India where the oath was scheduled on the midnight of the 15th.[97] On 14 August 1947, the new Dominion of Pakistan came into being, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah sworn in as its first Governor-General in Karachi. The following day, 15 August 1947, India, now Dominion of India, became an independent country, with official ceremonies taking place in New Delhi, Jawaharlal Nehru assuming the office of prime minister. Mountbatten remained in New Delhi for 10 months, serving as the first governor-general of an independent India until June 1948.[98] Gandhi remained in Bengal to work with the new refugees from the partitioned subcontinent.

Geographic partition, 1947

[edit]Mountbatten Plan

[edit]

At a press conference on 3 June 1947, Lord Mountbatten announced the date of independence – 14 August 1947 – and also outlined the actual division of British India between the two new dominions in what became known as the "Mountbatten Plan" or the "3 June Plan". The plan's main points were:

- Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims in Punjab and Bengal legislative assemblies would meet and vote for partition. If a simple majority of either group wanted partition, then these provinces would be divided.

- Sind and Baluchistan were to make their own decision.[99]

- The fate of North-West Frontier Province and Sylhet district of Assam was to be decided by a referendum.

- The separate independence of Bengal was ruled out.

- A boundary commission to be set up in case of partition.

The Indian political leaders had accepted the Plan on 2 June. It could not deal with the question of the princely states, which were not British possessions, but on 3 June Mountbatten advised them against remaining independent and urged them to join one of the two new Dominions.[100]

The Muslim League's demands for a separate country were thus conceded. The Congress's position on unity was also taken into account while making Pakistan as small as possible. Mountbatten's formula was to divide India and, at the same time, retain maximum possible unity. Abul Kalam Azad expressed concern over the likelihood of violent riots, to which Mountbatten replied:

At least on this question I shall give you complete assurance. I shall see to it that there is no bloodshed and riot. I am a soldier and not a civilian. Once the partition is accepted in principle, I shall issue orders to see that there are no communal disturbances anywhere in the country. If there should be the slightest agitation, I shall adopt the sternest measures to nip the trouble in the bud.[101]

Jagmohan has stated that this and what followed showed a "glaring failure of the government machinery."[101]

On 3 June 1947, the partition plan was accepted by the Congress Working Committee.[102] Boloji[unreliable source?] states that in Punjab, there were no riots, but there was communal tension, while Gandhi was reportedly isolated by Nehru and Patel and observed maun vrat (day of silence). Mountbatten visited Gandhi and said he hoped that he would not oppose the partition, to which Gandhi wrote the reply: "Have I ever opposed you?"[103]

Within British India, the border between India and Pakistan (the Radcliffe Line) was determined by a British Government-commissioned report prepared under the chairmanship of a London barrister, Sir Cyril Radcliffe. Pakistan came into being with two non-contiguous areas, East Pakistan (today Bangladesh) and West Pakistan, separated geographically by India. India was formed out of the majority Hindu regions of British India, and Pakistan from the majority Muslim areas.

On 18 July 1947, the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act that finalized the arrangements for partition and abandoned British suzerainty over the princely states, of which there were several hundred, leaving them free to choose whether to accede to one of the new dominions or to remain independent outside both.[104] The Government of India Act 1935 was adapted to provide a legal framework for the new dominions.

Following its creation as a new country in August 1947, Pakistan applied for membership of the United Nations and was accepted by the General Assembly on 30 September 1947. The Dominion of India continued to have the existing seat as India had been a founding member of the United Nations since 1945.[105]

Punjab Boundary Commission

[edit]

The Punjab—the region of the five rivers east of Indus: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—consists of inter-fluvial doabs ('two rivers'), or tracts of land lying between two confluent rivers (see map on the right):

- the Sindh-Sagar doab (between Indus and Jhelum);

- the Jech doab (Jhelum/Chenab);

- the Rechna doab (Chenab/Ravi);

- the Bari doab (Ravi/Beas); and

- the Bist doab (Beas/Sutlej).

In early 1947, in the months leading up to the deliberations of the Punjab Boundary Commission, the main disputed areas appeared to be in the Bari and Bist doabs. Some areas in the Rechna doab were claimed by the Congress and Sikhs. In the Bari doab, the districts of Gurdaspur, Amritsar, Lahore, and Montgomery were all disputed.[106] All districts (other than Amritsar, which was 46.5% Muslim) had Muslim majorities; albeit, in Gurdaspur, the Muslim majority, at 51.1%, was slender. At a smaller area-scale, only three tehsils (sub-units of a district) in the Bari doab had non-Muslim majorities: Pathankot, in the extreme north of Gurdaspur, which was not in dispute; and Amritsar and Tarn Taran in Amritsar district. Nonetheless, there were four Muslim-majority tehsils east of Beas-Sutlej, in two of which Muslims outnumbered Hindus and Sikhs together.[106]

Before the Boundary Commission began formal hearings, governments were set up for the East and the West Punjab regions. Their territories were provisionally divided by "notional division" based on simple district majorities. In both the Punjab and Bengal, the Boundary Commission consisted of two Muslim and two non-Muslim judges with Sir Cyril Radcliffe as a common chairman.[106] The mission of the Punjab commission was worded generally as: "To demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of Punjab, based on ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims. In doing so, it will take into account other factors." Each side (the Muslims and the Congress/Sikhs) presented its claim through counsel with no liberty to bargain. The judges, too, had no mandate to compromise, and on all major issues they "divided two and two, leaving Sir Cyril Radcliffe the invidious task of making the actual decisions."[106]

Independence, migration, and displacement

[edit]-

Train to Pakistan being given an honor-guard send-off. New Delhi railway station, 1947.

-

Rural Sikhs in a long oxcart train headed towards India, 1947.

-

Two Muslim men (in a rural refugee train headed towards Pakistan) carrying an old woman in a makeshift doli or palanquin, 1947.

-

A refugee train on its way to Punjab, Pakistan.

Mass migration occurred between the two newly formed states in the months immediately following the partition. There was no conception that population transfers would be necessary because of the partitioning. Religious minorities were expected to stay put in the states they found themselves residing. An exception was made for Punjab, where the transfer of populations was organized because of the communal violence affecting the province; this did not apply to other provinces.[107][108]

The population of undivided India in 1947 was about 390 million. Following the partition, there were perhaps 330 million people in India, 30 million in West Pakistan, and 30 million people in East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh).[109] Once the boundaries were established, about 14.5 million people crossed the borders to what they hoped was the relative safety of religious majority. The 1951 Census of Pakistan identified the number of displaced persons in Pakistan at 7,226,600, presumably all Muslims who had entered Pakistan from India; the 1951 Census of India counted 7,295,870 displaced persons, apparently all Hindus and Sikhs who had moved to India from Pakistan immediately after the partition.[110]

During Partition, a full population exchange was a contentious issue that received differing opinions among Indian leaders. B.R. Ambedkar and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel supported the idea of a complete population exchange between India and Pakistan. This meant that all the 42 million Muslims in India would move to Pakistan, while all the 19 million Hindus, Sikhs and other minorities in West and East Pakistan would migrate to India. Their rationale was rooted in ensuring lasting communal peace by eliminating the possibility of future inter-religious conflicts and reducing the risk of large-scale violence.[111] Ambedkar had argued in his writings, including Thoughts on Linguistic States, that such a population exchange, though harsh, was a practical solution to the communal problem that had led to Partition.[112][113] Similarly, Patel, the Iron Man of India, believed that the lingering presence of hostile minorities could lead to future instability.[114][115][116] They saw the success of the earlier population exchange between Greece and Turkey after the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) as a precedent.[117] However, this proposal was rejected by Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi, who strongly opposed the idea of compulsory population exchange. Nehru and Gandhi upheld the vision of a secular India where communities could coexist peacefully regardless of religion. They believed that a forced population transfer would cause immense suffering and disrupt the social fabric. Gandhi, in particular, had faith in Hindu-Muslim unity and insisted that Muslims who chose to stay in India should be welcomed as equal citizens.[118] As a result, the full population exchange did not occur.[119][120] While a partial migration took place, with around 14.5 million people crossing borders amidst horrific violence, millions remained on both sides. This decision had profound consequences. India retained its Muslim population, which grew to become a significant minority, while Pakistan's Hindu and Sikh populations dwindled drastically over the decades due to migration and persecution.[121][122] The absence of a full exchange has led to enduring communal tensions and periodic conflicts over the years, with proponents arguing that such an exchange might have prevented these issues.[123]

Regions affected by partition

[edit]The newly formed governments had not anticipated, and were completely unequipped for, a two-way migration of such staggering magnitude. Massive violence and slaughter occurred on both sides of the new India–Pakistan border.[124]

On 13 January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi started his fast with the goal of stopping the violence. Over 100 religious leaders gathered at Birla House and accepted the conditions of Gandhi. Thousands of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs gathered outside Birla house to uphold peace and unity. Representatives of organisations including Hindu Mahasabha, Jamait-ul-Ulema, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), visited Birla house to pledge communal harmony and the end of violence.[125] Maulana Azad, Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan's High Commissioner to India Zahid Hussain also made their visit.[126] By 18 January, Gandhi agreed to break his fast. This fast is credited for putting an end to communal violence.[127][128][129][130][131]

While estimates of the number of deaths vary greatly, ranging from 200,000 to 2,000,000, most of the scholars accept approximately 1 million died in the partition violence.[132] The worst case of violence among all regions is concluded to have taken place in Punjab.[133][134][135]

Punjab

[edit]

The Partition of India split the former British province of Punjab between the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. The mostly Muslim western part of the province became Pakistan's Punjab province; the mostly Hindu and Sikh eastern part became India's East Punjab state (later divided into the new states of Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh). Many Hindus and Sikhs lived in the west, and many Muslims lived in the east, and the fears of all such minorities were so great that the partition saw many people displaced and much inter-communal violence. Some have described the violence in Punjab as a retributive genocide.[136] Total migration across Punjab during the partition is estimated at 12 million people;[c] around 6.5 million Muslims moved into West Punjab, and 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs moved into East Punjab.

Virtually no Muslim survived in East Punjab (except in Malerkotla and Nuh) and virtually no Hindu or Sikh survived in West Punjab (except in Rahim Yar Khan and Bahawalpur).[138]

Lawrence James observed that "Sir Francis Mudie, the governor of West Punjab, estimated that 500,000 Muslims died trying to enter his province, while the British High Commissioner in Karachi put the full total at 800,000. This makes nonsense of the claim by Mountbatten and his partisans that only 200,000 were killed": [James 1998: 636].[139]

During this period, many alleged that Sikh leader Tara Singh was endorsing the killing of Muslims. On 3 March 1947, at Lahore, Singh, along with about 500 Sikhs, declared from a dais "Death to Pakistan."[140] According to political scientist Ishtiaq Ahmed:[141][142][143][144]

On March 3, radical Sikh leader Master Tara Singh famously flashed his kirpan (sword) outside the Punjab Assembly, calling for the destruction of the Pakistan idea prompting violent response by the Muslims mainly against Sikhs but also Hindus, in the Muslim-majority districts of northern Punjab. Yet, at the end of that year, more Muslims had been killed in East Punjab than Hindus and Sikhs together in West Punjab.

Nehru wrote to Gandhi on 22 August that, up to that point, twice as many Muslims had been killed in East Punjab than Hindus and Sikhs in West Punjab.[145]

Bengal

[edit]The province of Bengal was divided into the two separate entities of West Bengal, awarded to the Dominion of India, and East Bengal, awarded to the Dominion of Pakistan. East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan in 1955,[citation needed] and later became the independent nation of Bangladesh after the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

The districts of Murshidabad and Malda, located on the right bank of the Ganges, were given to India despite having Muslim majorities. The Hindu-majority Khulna District, located on the mouths of the Ganges and surrounded by Muslim-majority districts, were given to Pakistan, as were the eastern-most Chittagong Hill Tracts.[146]

Thousands of Hindus, located in the districts of East Bengal, which were awarded to Pakistan, found themselves being attacked, and this religious persecution forced hundreds of thousands of Hindus from East Bengal to seek refuge in India. The massive influx of Hindu refugees into Calcutta affected the demographics of the city. Many Muslims left the city for East Pakistan, and the refugee families occupied some of their homes and properties.

Total migration across Bengal during the partition is estimated at 3.3 million: 2.6 million Hindus moved from East Pakistan to India and 0.7 million Muslims moved from India to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

Chittagong Hill Tracts

[edit]The sparsely populated Chittagong Hill Tracts were a special case. Located on the eastern limits of Bengal, it provided the Muslim-majority Chittagong with a hinterland. Despite the Tracts' 98.5% Buddhist majority in 1947[147] the territory was given to Pakistan.[146]

Sindh

[edit]There was no mass violence in Sindh as there was in Punjab and Bengal. At the time of partition, the majority of Sindh's prosperous upper and middle class was Hindu. The Hindus were mostly concentrated in cities and formed the majority of the population in cities including Hyderabad, Karachi, Shikarpur, and Sukkur. During the initial months after partition, only some Hindus migrated. In late 1947, the situation began to change. Large numbers of Muslims refugees from India started arriving in Sindh and began to live in crowded refugee camps.[148]

On 6 December 1947, communal violence broke out in Ajmer in India, precipitated by an argument between some Sindhi Hindu refugees and local Muslims in the Dargah Bazaar. Violence in Ajmer again broke out in the middle of December with stabbings, looting and arson resulting in mostly Muslim casualties.[149] Many Muslims fled across the Thar Desert to Sindh in Pakistan.[149] This sparked further anti-Hindu riots in Hyderabad, Sindh. On 6 January anti-Hindu riots broke out in Karachi, leading to an estimate of 1100 casualties.[149][150] The arrival of Sindhi Hindu refugees in North Gujarat's town of Godhra in March 1948 again sparked riots there which led to more emigration of Muslims from Godhra to Pakistan.[149] These events triggered the large scale exodus of Hindus. An estimated 1.2 – 1.4 million Hindus migrated to India primarily by ship or train.[148]

Despite the migration, a significant Sindhi Hindu population still resides in Pakistan's Sindh province, where they number at around 2.3 million as per Pakistan's 1998 census. Some districts in Sindh had a Hindu majority like Tharparkar District, Umerkot, Mirpurkhas, Sanghar and Badin.[151] Due to the religious persecution of Hindus in Pakistan, Hindus from Sindh are still migrating to India.[152]

| Religious group |

1941[153]: 28 [g] | 1951[154]: 22–26 [h] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

3,462,015 | 71.52% | 5,535,645 | 91.53% |

| Hinduism |

1,279,530 | 26.43% | 482,560 | 7.98% |

| Sikhism |

32,627 | 0.67% | — | — |

| Christianity |

20,304 | 0.42% | 22,601 | 0.37% |

| Tribal | 37,598 | 0.78% | — | — |

| Zoroastrianism |

3,841 | 0.08% | 5,046 | 0.08% |

| Jainism |

3,687 | 0.08% | — | — |

| Judaism |

1,082 | 0.02% | — | — |

| Buddhism |

111 | 0.002% | 670 | 0.01% |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 1,226 | 0.02% |

| Total Population | 4,840,795 | 100% | 6,047,748 | 100% |

Gujarat

[edit]It experienced large refugee migrations. An estimated 642,000 Muslims migrated to Pakistan, of which 75% went to Karachi largely due to business interests. The 1951 Census registered a drop of the Muslim population in the state from 13% in 1941 to 7% in 1951.[155]

The number of incoming refugees was also quite large, with over a million people migrating to Gujarat. These Hindu refugees were largely Sindhi and Gujarati.[156]

Delhi

[edit]

For centuries Delhi had been the capital of the Mughal Empire from Babur to the successors of Aurangzeb and previous Turkic Muslim rulers of North India. The series of Islamic rulers keeping Delhi as a stronghold of their empires left a vast array of Islamic architecture in Delhi, and a strong Islamic culture permeated the city.[citation needed] In 1911, when the British Raj shifted their colonial capital from Calcutta to Delhi, the nature of the city began changing. The core of the city was called 'Lutyens' Delhi,' named after the British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, and was designed to service the needs of the small but growing population of the British elite. Nevertheless, the 1941 census listed Delhi's population as being 33.2% Muslim.[157]: 80

As refugees began pouring into Delhi in 1947, the city was ill-equipped to deal with the influx of refugees. Refugees "spread themselves out wherever they could. They thronged into camps ... colleges, temples, gurudwaras, dharmshalas, military barracks, and gardens."[158] By 1950, the government began allowing squatters to construct houses in certain portions of the city. As a result, neighbourhoods such as Lajpat Nagar and Patel Nagar sprang into existence, which carry a distinct Punjabi character to this day. As thousands of Hindu and Sikh refugees from West Punjab and North-West Frontier Province fled to the city, upheavals ensued as communal pogroms rocked the historical stronghold of Indo-Islamic culture and politics. A Pakistani diplomat in Delhi, Hussain, alleged that the Indian government was intent on eliminating Delhi's Muslim population or was indifferent to their fate. He reported that army troops openly gunned down innocent Muslims.[159] Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru estimated 1,000 casualties in the city. Other sources put the casualty rate 20 times higher. Gyanendra Pandey's 2010 account of the violence in Delhi puts the figure of Muslim casualties in Delhi at between 20,000 and 25,000.[160]

Tens of thousands of Muslims were driven to refugee camps regardless of their political affiliations, and numerous historical sites in Delhi such as the Purana Qila, Idgah, and Nizamuddin were transformed into refugee camps. In fact, many Hindu and Sikh refugees eventually occupied the abandoned houses of Delhi's Muslim inhabitants.[161]

At the culmination of the tensions, total migration in Delhi during the partition is estimated at 830,000 people; around 330,000 Muslims had migrated to Pakistan and around 500,000 Hindus and Sikhs migrated from Pakistan to Delhi.[162] The 1951 Census registered a drop of the Muslim population in the city from 33.2% in 1941 to 5.7% in 1951.[163][164]: 298

| Religious group |

1941[157]: 80 | 1951[164]: 298 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Hinduism |

567,264 | 61.8% | 1,467,854 | 84.16% |

| Islam |

304,971 | 33.22% | 99,501 | 5.71% |

| Christianity |

17,475 | 1.9% | 18,685 | 1.07% |

| Sikhism |

16,157 | 1.76% | 137,096 | 7.86% |

| Jainism |

11,287 | 1.23% | 20,174 | 1.16% |

| Zoroastrianism |

284 | 0.03% | 164 | 0.01% |

| Buddhism |

150 | 0.02% | 503 | 0.03% |

| Judaism |

55 | 0.01% | 90 | 0.01% |

| Others | 296 | 0.03% | 5 | 0% |

| Total population | 917,939 | 100% | 1,744,072 | 100% |

Princely states

[edit]In several cases, rulers of princely states were involved in communal violence or did not do enough to stop in time. Some rulers were away from their states for the summer, such as those of the Sikh states. Some believe that the rulers were whisked away by communal ministers in large part to avoid responsibility for the soon-to-come ethnic cleansing.[citation needed] In Bhawalpur and Patiala, upon the return of their ruler to the state, there was a marked decrease in violence, and the rulers consequently stood against the cleansing. The Nawab of Bahawalpur was away in Europe and returned on 1 October, shortening his trip. A bitter Hassan Suhrawardy would write to Mahatma Gandhi:

What is the use now, of the Maharaja of Patiala, when all the Muslims have been eliminated, standing up as the champion of peace and order?[165]

With the exceptions of Jind and Kapurthala, the violence was well organised in the Sikh states, with logistics provided by local government.[166] In Patiala and Faridkot, the Maharajas responded to the call of Master Tara Singh to cleanse India of Muslims. The Maharaja of Patiala was offered the headship of a future united Sikh state that would rise from the "ashes of a Punjab civil war."[167] The Maharaja of Faridkot, Harinder Singh, is reported to have listened to stories of the massacres with great interest going so far as to ask for "juicy details" of the carnage.[168] The Maharaja of Bharatpur State personally witnessed the cleansing of Muslim Meos at Khumbar and Deeg. When reproached by Muslims for his actions, Brijendra Singh retorted by saying: "Why come to me? Go to Jinnah."[169]

In Alwar and Bahawalpur communal sentiments extended to higher echelons of government, and the prime ministers of these States were said to have been involved in planning and directly overseeing the cleansing. In Bikaner, by contrast, the organisation occurred at much lower levels.[170]

Alwar and Bharatpur

[edit]In Alwar and Bharatpur, princely states of Rajputana (modern-day Rajasthan), there were bloody confrontations between the dominant, Hindu land-holding community and the Muslim cultivating community.[171] Well-organised bands of Hindu Jats, Ahirs and Gurjars, started attacking Muslim Meos in April 1947. By June, more than fifty Muslim villages had been destroyed. The Muslim League was outraged and demanded that the Viceroy provide Muslim troops. Accusations emerged in June of the involvement of Indian State Forces from Alwar and Bharatpur in the destruction of Muslim villages both inside their states and in British India.[172]

In the wake of unprecedented violent attacks unleashed against them in 1947, 100,000 Muslim Meos from Alwar and Bharatpur were forced to flee their homes, and an estimated 30,000 are said to have been massacred.[173] On 17 November, a column of 80,000 Meo refugees went to Pakistan. However, 10,000 stopped travelling due to the risks.[171]

Jammu and Kashmir

[edit]In September–November 1947 in the Jammu region of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, a large number of Muslims were killed, and others driven away to West Punjab. The impetus for this violence was partly due to the "harrowing stories of Muslim atrocities", brought by Hindu and Sikh refugees arriving to Jammu from West Punjab since March 1947. The killings were carried out by extremist Hindus and Sikhs, aided and abetted by the forces of the Jammu and Kashmir State, headed by the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir Hari Singh. Observers state that Hari Singh aimed to alter the demographics of the region by eliminating the Muslim population and ensure a Hindu majority.[174][175] This was followed by a massacre of Hindus and Sikhs starting in November 1947, in Rajouri and Mirpur by Pashtun tribal militias and Pakistani soldiers.[176] Women were raped and sexually assaulted, while many of those killed, raped and injured had come to these areas to escape massacres in West Punjab, which had become part of Pakistan.[176]

Resettlement of refugees: 1947–1951

[edit]Resettlement in India

[edit]According to the 1951 Census of India, 2% of India's population were refugees (1.3% from West Pakistan and 0.7% from East Pakistan).

The majority of Hindu and Sikh Punjabi refugees from West Punjab were settled in Delhi and East Punjab (including Haryana and Himachal Pradesh). Delhi received the largest number of refugees for a single city, with the population of Delhi showing an increase from under 1 million (917,939) in the Census of India, 1941, to a little less than 2 million (1,744,072) in the 1951 Census, despite a large number of Muslims leaving Delhi in 1947 to go to Pakistan whether voluntarily or by coercion.[177] The incoming refugees were housed in various historical and military locations such as the Purana Qila, Red Fort, and military barracks in Kingsway Camp (around the present Delhi University). The latter became the site of one of the largest refugee camps in northern India, with more than 35,000 refugees at any given time besides Kurukshetra camp near Panipat. The campsites were later converted into permanent housing through extensive building projects undertaken by the Government of India from 1948 onwards. Many housing colonies in Delhi came up around this period, like Lajpat Nagar, Rajinder Nagar, Nizamuddin East, Punjabi Bagh, Rehgar Pura, Jangpura, and Kingsway Camp. Several schemes such as the provision of education, employment opportunities, and easy loans to start businesses were provided for the refugees at the all-India level.[178] Many Punjabi Hindu refugees were also settled in Cities of Western and Central Uttar Pradesh. A Colony consisting largely of Sikhs and Punjabi Hindus was also founded in Central Mumbai's Sion Koliwada region, and named Guru Tegh Bahadur Nagar.[179]

Hindus fleeing from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) were settled across Eastern, Central and Northeastern India, many ending up in neighbouring Indian states such as West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura. Substantial number of refugees were also settled in Madhya Pradesh (incl. Chhattisgarh) Bihar (incl. Jharkhand), Odisha and Andaman islands (where Bengalis today form the largest linguistic group)[180][181]

Sindhi Hindus settled predominantly in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. Substantial numbers, however, were also settled in Madhya Pradesh, A few also settled in Delhi. A new township was established for Sindhi Hindu refugees in Maharashtra. The Governor-General of India, Sir Rajagopalachari, laid the foundation for this township and named it Ulhasnagar ('city of joy').

Substantial communities of Hindu Gujarati and Marathi Refugees who had lived in the cities of Sindh and Southern Punjab were also resettled in the cities of modern-day Gujarat and Maharashtra.[156][182]

A small community of Pashtun Hindus from Loralai, Balochistan was also settled in Jaipur. Today they number around 1,000.[183]

Refugee camps

[edit]The list below shows the number of relief camps in districts of Punjab and their population up to December 1948.[184]

| District (up to December 1948) | No. of camps | No. of persons |

|---|---|---|

| Amritsar | 5 | 129,398 |

| Gurdaspur | 4 | 3,500 |

| Ferozpur | 5 | 53,000 |

| Ludhiana | 1 | 25,000 |

| Jalandhar | 19 | 60,000 |

| Hoshiarpur | 1 | 11,701 |

| Hissar | 3 | 3,797 |

| Rohtak | 2 | 50,000 |

| Ambala | 1 | 50,000 |

| Karnal (including Kurukshetra) | 4 | 325,000 |

| Gurugram (Gurgaon) | 40 | 20,000 |

| Total | 85 | 721,396 |

Resettlement in Pakistan

[edit]The 1951 Census of Pakistan recorded that the most significant number of Muslim refugees came from the East Punjab and nearby Rajputana states (Alwar and Bharatpur). They numbered 5,783,100 and constituted 80.1% of Pakistan's total refugee population.[185] This was the effect of the retributive ethnic cleansing on both sides of the Punjab where the Muslim population of East Punjab was forcibly expelled like the Hindu/Sikh population in West Punjab.

Migration from other regions of India were as follows: Bihar, West Bengal, and Orissa, 700,300 or 9.8%; UP and Delhi 464,200 or 6.4%; Gujarat and Bombay, 160,400 or 2.2%; Bhopal and Hyderabad 95,200 or 1.2%; and Madras and Mysore 18,000 or 0.2%.[185]

So far as their settlement in Pakistan is concerned, 97.4% of the refugees from East Punjab and its contiguous areas went to West Punjab; 95.9% from Bihar, West Bengal and Orissa to the erstwhile East Pakistan; 95.5% from UP and Delhi to West Pakistan, mainly in Karachi Division of Sindh; 97.2% from Bhopal and Hyderabad to West Pakistan, mainly Karachi; and 98.9% from Bombay and Gujarat to West Pakistan, largely to Karachi; and 98.9% from Madras and Mysore went to West Pakistan, mainly Karachi.[185]

West Punjab received the largest number of refugees (73.1%), mainly from East Punjab and its contiguous areas. Sindh received the second largest number of refugees, 16.1% of the total migrants, while the Karachi division of Sindh received 8.5% of the total migrant population. East Bengal received the third-largest number of refugees, 699,100, who constituted 9.7% of the total Muslim refugee population in Pakistan. 66.7% of the refugees in East Bengal originated from West Bengal, 14.5% from Bihar and 11.8% from Assam.[186]

NWFP and Baluchistan received the lowest number of migrants. NWFP received 51,100 migrants (0.7% of the migrant population) while Baluchistan received 28,000 (0.4% of the migrant population).

The government undertook a census of refugees in West Punjab in 1948, which displayed their place of origin in India.

Data

[edit]

|

|

|

Missing people

[edit]A study of the total population inflows and outflows in the districts of Punjab, using the data provided by the 1931 and 1951 Census has led to an estimate of 1.3 million missing Muslims who left western India but did not reach Pakistan.[139] The corresponding number of missing Hindus/Sikhs along the western border is estimated to be approximately 0.8 million.[188] This puts the total of missing people, due to partition-related migration along the Punjab border, to around 2.2 million.[188] Another study of the demographic consequences of partition in the Punjab region using the 1931, 1941 and 1951 censuses concluded that between 2.3 and 3.2 million people went missing in the Punjab.[189]

Rehabilitation of women

[edit]Both sides promised each other that they would try to restore women abducted and raped during the riots. The Indian government claimed that 33,000 Hindu and Sikh women were abducted, and the Pakistani government claimed that 50,000 Muslim women were abducted during riots. By 1949, there were legal claims that 12,000 women had been recovered in India and 6,000 in Pakistan.[190] By 1954, there were 20,728 Muslim women recovered from India, and 9,032 Hindu and Sikh women recovered from Pakistan.[191] Most of the Hindu and Sikh women refused to go back to India, fearing that their families would never accept them, a fear mirrored by Muslim women.[192]

Some scholars have noted some 'positive' effects of partition on women in both Bengal and Punjab. In Bengal, it had some emancipatory effects on refugee women from East Bengal, who took up jobs to help their families, entered the public space and participated in political movements. The disintegration of traditional family structures could have increased the space for the agency of women. Many women also actively participated in the communist movement that later took place in West Bengal of India. Regarding Indian Punjab, one scholar has noted, "Partition narrowed the physical spaces and enlarged the social spaces available to women, thereby affecting the practice of purda or seclusion, modified the impact of caste and regional culture on marriage arrangements and widened the channels of educational mobility and employment for girls and women."[193]

Post-partition migration

[edit]Pakistan

[edit]Due to persecution of Muslims in India, even after the 1951 Census, many Muslim families from India continued migrating to Pakistan throughout the 1950s and the early 1960s. According to historian Omar Khalidi, the Indian Muslim migration to West Pakistan between December 1947 and December 1971 was from Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. The next stage of migration was between 1973 and the 1990s, and the primary destination for these migrants was Karachi and other urban centres in Sindh.[194]

In 1959, the International Labour Organization (ILO) published a report stating that from 1951 to 1956, a total of 650,000 Muslims from India relocated to West Pakistan.[194] However, Visaria (1969) raised doubts about the authenticity of the claims about Indian Muslim migration to Pakistan, since the 1961 Census of Pakistan did not corroborate these figures. However, the 1961 Census of Pakistan did incorporate a statement suggesting that there had been a migration of 800,000 people from India to Pakistan throughout the previous decade.[195] Of those who left for Pakistan, most never came back.[citation needed]

Indian Muslim migration to Pakistan declined drastically in the 1970s, a trend noticed by the Pakistani authorities. In June 1995, Pakistan's interior minister, Naseerullah Babar, informed the National Assembly that between the period of 1973–1994, as many as 800,000 visitors came from India on valid travel documents. Of these only 3,393 stayed.[194] In a related trend, intermarriages between Indian and Pakistani Muslims have declined sharply. According to a November 1995 statement of Riaz Khokhar, the Pakistani High Commissioner in New Delhi, the number of cross-border marriages has dropped from 40,000 a year in the 1950s and 1960s to barely 300 annually.[194]

In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, 3,500 Muslim families migrated from the Indian part of the Thar Desert to the Pakistani section of the Thar Desert.[196] 400 families were settled in Nagar after the 1965 war and an additional 3,000 settled in the Chachro taluka in Sindh province of West Pakistan.[197] The government of Pakistan provided each family with 12 acres of land. According to government records, this land totalled 42,000 acres.[197]

The 1951 census in Pakistan recorded 671,000 refugees in East Pakistan, the majority of which came from West Bengal. The rest were from Bihar.[198] According to the ILO in the period 1951–1956, half a million Indian Muslims migrated to East Pakistan.[194] By 1961 the numbers reached 850,000. In the aftermath of the riots in Ranchi and Jamshedpur, Biharis continued to migrate to East Pakistan well into the late sixties and added up to around a million.[199] Crude estimates suggest that about 1.5 million Muslims migrated from West Bengal and Bihar to East Bengal in the two decades after partition.[200]

India

[edit]Due to religious persecution in Pakistan, Hindus continue to flee to India. Most of them tend to settle in the state of Rajasthan in India.[201] According to data of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, just around 1,000 Hindu families fled to India in 2013.[201] In May 2014, a member of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), Ramesh Kumar Vankwani, revealed in the National Assembly of Pakistan that around 5,000 Hindus are migrating from Pakistan to India every year.[202] Since India is not a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, it refuses to recognise Pakistani Hindu migrants as refugees.[201]

The population in the Tharparkar district in the Sindh province of West Pakistan was 80% Hindu and 20% Muslim at the time of independence in 1947. During the Indo-Pakistani Wars of 1965 and 1971, an estimated 1,500 Hindu families fled to India, which led to a massive demographic shift in the district.[196][203] During these same wars, 23,300 Hindu families also migrated to Jammu Division from Azad Kashmir and West Punjab.[204]

The migration of Hindus from East Pakistan to India continued unabated after partition. The 1951 census in India recorded that 2.5 million refugees arrived from East Pakistan, of which 2.1 million migrated to West Bengal while the rest migrated to Assam, Tripura, and other states.[198] These refugees arrived in waves and did not come solely at partition. By 1973, their number reached over 6 million. The following data displays the major waves of refugees from East Pakistan and the incidents which precipitated the migrations:[205][206]

Post-partition migration to India from East Pakistan

[edit]| Year | Reason | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Partition | 344,000 |

| 1948 | Fear due to the annexation of Hyderabad | 786,000 |

| 1950 | 1950 Barisal Riots | 1,575,000 |

| 1956 | Pakistan becomes Islamic Republic | 320,000 |

| 1964 | Riots over Hazratbal incident | 693,000 |

| 1965 | Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 | 107,000 |

| 1971 | Bangladesh liberation war | 1,500,000 |

| 1947–1973 | Total | 6,000,000[207] |