Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

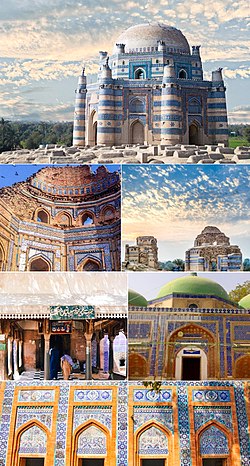

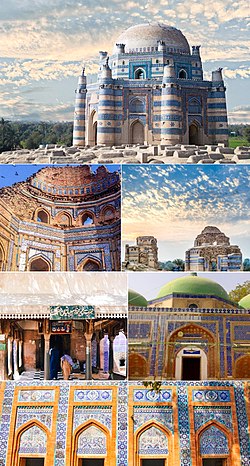

Uch (Punjabi: اچ; Urdu: اوچ), frequently referred to as Uch Sharīf (Punjabi: اچ شریف; Urdu: اوچ شریف; "Noble Uch"), is a historic city in Pakistan's Punjab province. Uch may have been founded as Alexandria on the Indus, a town founded by Alexander the Great during his invasion of the Indus Valley.[1][2] Uch was an early stronghold during the Muslim conquest of the subcontinent. It is also known as the home for the Naqvi/Bukharis after the migration from Bukhara. Uch was a regional metropolitan centre between the 12th and 17th centuries,[2] and became refuge for Muslim religious scholars fleeing persecution from other lands.[2] Though Uch is now a relatively small city, it is renowned for its intact historic urban fabric, and for its collection of shrines dedicated to Muslim mystics (Sufis) from the 12th to 15th centuries that are embellished with extensive tile work, and were built in the distinct architectural style of southern Punjab.[2]

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]Uch Sharif was previous known by the name of Bhatiah until the 12th century.[1] The origins of the city's current name are unclear. In one legend, Jalaluddin Surkh-Posh Bukhari, the renowned Central Asian Sufi mystic from Bukhara, arrived in Uch and converted the daughter of the town's ruler, Sunandapuri, to Islam. Upon her conversion, Jalaluddin Bukhari requested her to build a fortress which he named Uch, or "High."[1] According to another version of the legend, the princess converted by Bukhari was actually a Buddhist princess named Ucha Rani, and the city's name derives from her.[3] Uch was not universally recognized as the area's name for quite some time, and the city was not referred to by early Muslim historians by the name Uch.[1] Uch, for example, is likely the town recorded as Bhatia that was invaded by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1006.[1]

History

[edit]Early

[edit]Uch Sharif may have been founded in 325 BCE by Alexander the Great as the city of Alexandria on the Indus (Greek: Ἀλεξάνδρεια ἡ ἐν Ἰνδῷ), according to British officer and archaeologist Alexander Cunningham.[1] The city was reportedly settled by natives of the Greek region of Thrace,[4] and was located at the confluence of the Acesines river with the Indus.[5] Uch was once located on the banks of the Indus River, though the river has since shifted its course,[6] and the confluence of the two rivers has shifted approximately 40 km (25 miles) southwest.

Medieval

[edit]In 712 CE, Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Uch. Few details exist of the city in the centuries prior to his invasion. Uch was probably the town recorded as Bhatia that was conquered in 1006 by Mahmud of Ghazni.[1] Following the schism between the Nizari and Musta'li sects of Ismaili Shi'ism in 1094, Uch became a centre of Nizari missionary activity for several centuries,[7] and today the town and surrounding region are littered with numerous tombs of prominent pīrs,[7] as well as pious daughters and wives of those Sufi pirs.[8]

The region around Uch and Multan remained centre of Hindu Vaishnavite and Surya pilgrimage throughout the medieval era.[8] Their interactions with Ismaili tradition resulted in the creation of the Satpanth tradition.[8] Throughout this era, Uch was at the centre of a region that was steeped in both Vedic and Islamic traditions.[8] The city would later become a centre of Suhrwadi Sufism, with the establishment of the order by Bahauddin Zakariya in nearby Multan in the early 1200s.[9]

Muhammad of Ghor conquered Uch and nearby Sultan in 1176 while it was still under the influence of the Ismaili Qarmatians. The town was likely captured from the Soomras based in Sindh.[10] Sindh's various dynasties had for centuries attempted to keep Uch and Multan under their sway.[11]

Mamluk era

[edit]

Soomra power was eroded by the advance of Nasir ad-Din Qabacha of what would later become the Mamluk dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate. Qabacha was declared Governor of Uch in 1204, he also controlled Multan and Sindh regions. Under his rule, Uch became the principal city of Upper Sindh.[1] Qabacha declared independence for his principality centred on Uch and Multan after the death of Sultan Aybak in 1211,[8] before marching onwards to capture Lahore,[8] thereby placing Qabacha's new Uch Sultanate in conflict with Sultan Iltutmish in Delhi. Qabacha briefly lost control of Uch to Taj al-Din Yildiz, though Uch was quickly returned to Qabacha's rule.[8]

While the power struggle ensued among Qabacha and Iltuthmish, Uch came under further pressure from the Khwarazmian dynasty based in Samarkand that had been displaced by the Mongol armies of Genghis Khan.[8] Following the defeat of his father by the Mongols in the mid 1210s, the last Khwarazmian Sultan, Jalal al-Din Mangburni, sacked and conquered Uch in 1224 after Qabacha refused to aid him in a campaign against Genghis Khan.[8] Jalal al-Din Mangburni was finally defeated by Genghis Khan in 1224 in a battle at Uch,[8] and was forced to flee to Persia. Khan attacked Multan on his return to Iran in 1224, though Sultan Qabacha was able to successfully defend that city.[8] Despite repeated invasions, the city remained a great centre of Muslim scholarship, as evidenced by the appointment of the renowned Persian historian Minhaj-i-Siraj as chief of the city's Firozi madrasa.[1]

In 1228, Qabacha's forces, weakened by Mongol and Khwarazmian invasions, lost Uch to Sultan Iltutmish of Delhi, and fled south to Bhakkar in Sindh,[8] where he was eventually captured and drowned in the Indus River as punishment.[13] Following the collapse of Qabacha's sultanate at the hands of Mongols and Khwarazmians, and the degradation of Lahore from years of conflict there,[14] Muslim power in north India shifted away from Punjab and towards the safer environs of Delhi.[8]

Mongol and Timurid invasions

[edit]

One of Uch's most celebrated saints, Jalaluddin Surkh-Posh Bukhari, migrated to Uch from Bukhara in 1244–45. In 1245–46, the Mongols again invaded Uch under Möngke Khan after receiving aid from the local Khokhar tribes.[10] in 1252, forces from Delhi were sent to the region in order to secure Uch from Mongol raiders, though Uch was again raided in 1258.[10] Uch was raided yet again by Mongols in 1304 and 1305.[15] Following the 1305 invasion, Uch came under the governorship of Ghazi Malik the governor of Multan and Depalpur, who would later seize Delhi and come to be known as Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq, founder of the Tughlaq dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate.[15] Uch was captured in 1398 by Pir Muhammad ibn Jahangir, grandson of Tamerlane,[16] allowing Khizr Khan to regain control of the area, before joining with the forces of the elder Tamerlane to sack Delhi and establish the Sayyid dynasty in 1414.[citation needed]

Langah sultanate

[edit]Uch Sharif then came under the control of the Langah Sultanate in the early 15th century, founded in nearby Multan by Budhan Khan, who assumed the title Mahmud Shah.[17] During the rule of Shah Husayn Langah, large numbers of Baloch settlers were invited to settle the region.[17] The city was placed under the jagir governorship of a Samma prince. In the mid-1400s, Muhammad Ghaus Gilani, a descendant of the Persian saint Abdul Qadir Gilani, established a Khanqah monastery in Uch, thereby establishing the city as a centre of the Qadiriyya Sufi order which would later become the dominant order of Punjab.[18] Following the death of Shah Husayn, Uch's Samma rulers quickly allied themselves with Baloch chieftain Mir Chakar Rind.[19]

Mughal

[edit]Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, is believed to have visited Uch Sharif in the early 1500s, and left behind 5 relics, after meeting with the descendants of Jalaludin Bukhari.[20] In 1525 Uch was invaded by rulers of the Arghun dynasty of northern Sindh,[17] before falling to the forces of Pashtun king Sher Shah Suri in 1540.

Mughal Emperor Humayun entered Uch in late 1540, but was not welcomed by the city's inhabitants, and was defeated by the forces of Sher Shah Suri.[21] The city reverted to Arghun rule following the expulsion of Humayun, and the fall of Sher Shah Suri's short-lived empire.[15]

Uch Sharif became a part of the Mughal Empire during the reign of Akbar, and the city was a district of Multan province.[1] Under Mughal rule, the city continued to flourish as a centre of religious scholarship.[2] It was listed in the Ain-i-Akbari as a pargana in sarkar Multan, counted as part of the Bīrūn-i Panjnad ("Beyond the Five Rivers").[22]: 331 It was assessed at 1,910,140 dams in revenue and supplied a force of 100 cavalry and 400 infantry.[22]: 331

In 1680, the renowned Punjabi poet, Bulleh Shah, who is regarded as a saint by both Sufis and Sikhs, was born in Uch.[23] In 1751, Uch was attacked by Sardar Jahan Khan, general in the army of Ahmad Shah Durrani.[24]

Under the State of Bahawalpur

[edit]

Uch Sharif came under the control of the Bahawalpur princely state, which declared independence in 1748 following the collapse of the Durrani empire. Bahawalpur had become a vassal of the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, before becoming a dependency of the British Empire defined under an 1833 treaty. By 1836, the ruling Abbasi family stopped paying tribute to the Sikhs, and declared independence. Bahawalpur's ruling Abbasi family aligned themselves with the British during the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars, thereby guaranteeing its survival as a princely state.[25]

Flooding in the early 19th century caused serious damage to many of the city's tombs, including structural problems and the deterioration of masonry and finishes.[26]

Modern

[edit]Upon the independence of Pakistan in 1947, Uch Sharif had a population of around 2–3,000 people.[27] As part of Bahawalpur state, Uch Sharif was acceded to the new Pakistani state, but remained part of the autonomous Bahawalpur state until 1955 when it was fully amalgamated into Pakistan. Uch remains a relatively small city, but is an important tourist and pilgrimage destination on account of its numerous tombs and shrines.[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 4,170 | — |

| 1961 | 5,483 | +2.78% |

| 1972 | 8,491 | +4.06% |

| 1981 | 13,386 | +5.19% |

| 1998 | 20,476 | +2.53% |

| 2017 | 42,684 | +3.94% |

| 2023 | 98,852 | +15.02% |

| Sources: [28][29] | ||

The population of city in 1998 was 20,476 but according to the 2023 Census of Pakistan, the population has risen to 98,852.[30]

Geography

[edit]Uch Sharif is located 84 km away from Bahawalpur. Formerly located at the confluence of the Indus and Chenab rivers, the river shifted course,[6] and is now 25 miles (40 km) from that confluence, which has moved to Mithankot. The city now lies on a large Alluvial plain near south of the Chenab river. To the southeast lay the vast expanses of the Cholistan Desert.

Uch Sharif is located at an elevation of 113 meters above sea level. Latitude of 29.23895° or 29° 14' 20" north and longitude 71.06148° or 71° 3' 41" east.

Cityscape

[edit]Uch Sharif has retained much of its historic urban fabric intact.[2] The historic town is divided into three localities: Uch Bukhari, named for the saints from Bukhara, Uch Gilani (or Uch Jilani), named for the saints from Persia, and Uch Mughlia, named for the descendants of Mongol invaders who had settled in that quarter.[31] Monuments are scattered throughout the city, and are connected by narrow lanes and winding bazaars.[2] The most notable collection, called the Uch Monument Complex, is located at the old city's western edge. The old core is next to a large field used as a mela ground,[2] or fair ground for urs festivals dedicated to the town's saints.

Climate

[edit]Uch features an arid climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) with very hot summers and mild winters.

| Climate data for nearby Multan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.3 (82.9) |

32.0 (89.6) |

39.0 (102.2) |

45.0 (113.0) |

48.9 (120.0) |

52.0 (125.6) |

52.2 (126.0) |

45.0 (113.0) |

42.5 (108.5) |

40.6 (105.1) |

36.0 (96.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

52.2 (126.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

40.4 (104.7) |

42.3 (108.1) |

39.2 (102.6) |

38.0 (100.4) |

37.2 (99.0) |

34.6 (94.3) |

28.5 (83.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

32.6 (90.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.4 (79.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

24.9 (76.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

17.9 (64.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−1 (30) |

3.3 (37.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−2 (28) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 7.2 (0.28) |

9.5 (0.37) |

19.5 (0.77) |

12.9 (0.51) |

9.8 (0.39) |

12.3 (0.48) |

61.3 (2.41) |

32.6 (1.28) |

10.8 (0.43) |

1.7 (0.07) |

2.3 (0.09) |

6.9 (0.27) |

186.8 (7.35) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 222.3 | 211.6 | 250.8 | 273.3 | 293.5 | 266.8 | 265.0 | 277.6 | 277.6 | 274.9 | 255.0 | 229.2 | 3,097.6 |

| Source: NOAA (1961–1990)[32] | |||||||||||||

Uch Monument Complex

[edit]

17 tiled funerary monuments and associated structures remain tightly knit into the urban fabric of Uch. The shrines, notably the tombs of Syed Jalaluddin Bukhari and his family, are built in a regional vernacular style particular to southern Punjab, with tile work imported from the nearby city of Multan.[33] These structures were typically domed tombs on octagonal bases, with elements of Tughlaq military architecture, such as the addition of decorative bastions and crenellations.[34]

Three shrines built over the course of 200 years are particularly well known, and along with an accompanying 1400 graves form the Uch Monument Complex,[2] a site tentatively inscribed on the list of UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites.[33] Of the shrines, the first is said to have been built for Sheikh Baha’al-Halim by his pupil, the Suharwardiya Sufi saint Jahaniyan Jahangasht (1307–1383), the second for the latter's great-granddaughter, Bibi Jawindi, in 1494, and the third for the latter's architect.

Flooding in the early 19th century caused serious damage to many of the city's tombs, including structural problems and the deterioration of masonry and finishes.[26] As the problems have persisted, the Uch Monument Complex was listed in the 1998 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund, and again in 2000 and 2002.[35] The Fund subsequently offered financial assistance for conservation from American Express.[36] In 2018, the World Bank provided a $500 million loan to the Punjab Government to restore several historical monuments, including the Tomb of Bibi Jawindi.[37]

Parliamentarians

[edit]- 2018 (Current)

- Syed Sami ul Hassan Gilani Member National Assembly PTI

- Makhdoom Syed Iftikhar Hussain Gillani Member Provincial Assembly PTI

- 2013

- Syed Ali Hassan Gillani Member National Assembly PML(N)

- Makhdoom Syed Iftikhar Hussain Gillani Member Provincial Assembly(BNAP)

- 2008

- Arif Aziz Sheikh Member National Assembly PPPP

- Makhdoom Syed Iftikhar Hussain Gillani Member Provincial Assembly PML(Q)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Imperial gazetteer of India: provincial series. Supt. of Govt. Print. 1908.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Uch Monuments". UNESCO Office in Bangkok. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Khan, Hasan Ali (8 August 2016). Constructing Islam on the Indus: The Material History of the Suhrawardi Sufi Order, 1200–1500 AD. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316827222.

- ^ The Macedonian Empire, by James R. Ashley p.54

- ^ Alexandria (Uch) - Livius.org

- ^ a b "Uch Monument". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ a b MacLean, Derryl N. (1989). Religion and Society in Arab Sind. BRILL. ISBN 9789004085510.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Asif, Manan Ahmed (19 September 2016). A Book of Conquest. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674660113.

- ^ Dasti, Humaira Faiz (1998). Multan, a province of the Mughal Empire, 1525-1751. Royal Book. ISBN 978-969-407-226-5.

- ^ a b c Wink, André (1997). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest : 11th-13th Centuries. BRILL. ISBN 9004102361.

- ^ Avasthy, Rama Shanker (1967). The Mughal Emperor Humayun. History Dept., University of Allahabad.

- ^ orientalarchitecture.com. "Asian Historical Architecture: A Photographic Survey". www.orientalarchitecture.com. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Dughlt, Mirza Muhammad Haidar (1 January 2008). A History of the Moghuls of Central Asi: The Tarikh-i-Rashidi. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9781605201504.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (16 October 2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521543293.

- ^ a b c Pakistan Quarterly. 1955.

- ^ Imperial gazetteer of India: provincial series. Supt. of Govt. Print. 1908.

- ^ a b c Rafiq, A.Q.; Baloch, N.A. The Regions of Sind, Baluchistan, Multan and Kashmir: the Historical, Social and Economic Setting (PDF). UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2019.

- ^ Dehlvi, Sadia (5 March 2012). The Sufi Courtyard: Dargahs Of Delhi. Harper Collins. ISBN 9789350294734.

- ^ Ibbetson, Sir Denzil; Maclagan, Sir Edward (December 1996). Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North West Frontier Province. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120605053.

- ^ Kohli, Surindar Singh (1969). Travels of Guru Nanak. Publication Bureau, Panjab University.

- ^ Qanungo, Kalika Ranjan (1965). Sher Shah and his times. Orient Longmans.

- ^ a b Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak (1891). The Ain-i-Akbari. Translated by Jarrett, Henry Sullivan. Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Ahmad, Saeed; Aḥmad, Saʻīd (2004). Great sufi wisdom Bulleh Shah, 1680-1752. Adnan Books. ISBN 978-969-8714-04-8.

- ^ (Firm), Cosmo Publications (2000). The Pakistan gazetteer. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 9788170208822.

- ^ Organization, Pattan Development (2006). Bahawalpur District: socio-political profile. Pattan Development Organization.

- ^ a b Colin Amery and Brian Curran, Vanishing Histories, Harry N. Abrams, New York, NY: 2001, p. 103.

- ^ The Panjab Past and Present. Department of Punjab Historical Studies, Punjabi University. 1969.

- ^ "Population by administrative units 1951-1998" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "Population by administrative units 1951-1998" (PDF). Lahore School.

- ^ "Uch (Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ "Uch Sharif". Humshehri. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Multan Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (FTP). Retrieved 16 January 2013.[dead ftp link] (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- ^ a b Burrison, John A. (16 June 2017). Global Clay: Themes in World Ceramic Traditions. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253031891.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Robert (1994). Islamic architecture : form, function, and meaning. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231101332. OCLC 30319450.

- ^ World Monuments Fund - Uch Monument Complex

- ^ Rina Saeed Khan, "New York group funds Uch conservation," Pakistan Daily Times, 16 January 2004.

- ^ "World Bank to give Punjab govt $500m to restore religious sites". Dawn.com. 18 April 2018.

- Henry George Raverty, Notes on Afghanistan and Baluchistan; (1878) [1] Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Uch Sharif

- Uch Sharif : New Photographs on Uch Sharif

- Uch : A detailed photographic description of all famous places of Uch Sharif

- Shrine of Bibi Jawindi, Uch Sharif

- UNESCO World Heritage Foundation - Tomb of Bibi Jawindi, Baha'al-Halim and Ustead and the Tomb and Mosque of Jalaluddin Bukhari

- Photographs

- Bibi Jawindi Tomb-ArchNet

- Livius Uch Picture Archive Archived 10 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Etymology

Name Derivation and Historical Usage

The settlement now known as Uch was referred to as Bhatiah prior to the 12th century, after which the name shifted to its current form.[7] The derivation of "Uch" remains uncertain, with proposed origins including the Sanskrit term ucha ("high"), alluding to the city's elevated position on a mound above the surrounding plains; the name of the Vedic goddess Ushas, adapted by Aryan settlers; Arabic auj ("peak" or "height"); or Turkish üç ("three"), potentially referencing the tripartite division of the town into Uch Bukhari, Uch Gilani, and Uch Sharif quarters, each associated with prominent Sufi lineages.[8][9] Some 19th-century scholars, including archaeologist Alexander Cunningham, conjectured a link to ancient Alexandria on the Indus, a foundation attributed to Alexander the Great in 325 BCE during his campaign in the region, though this identification lacks direct archaeological corroboration and is considered speculative.[8][10] The honorific "Sharif" was appended in medieval Islamic usage to signify the site's sanctity, tied to the tombs of Sufi saints such as Jalaluddin Bukhari (d. 1291 CE), whose arrival in the 12th century elevated Uch's status as a center of Islamic scholarship and pilgrimage; historical records from the Delhi Sultanate era onward consistently employ "Uch Sharif" to denote this religious prominence.[11][12]History

Ancient Foundations and Pre-Islamic Era

The region surrounding Uch, part of the Cholistan desert in southern Punjab, exhibits evidence of prehistoric human activity linked to the Indus Valley Civilization, with over 300 protohistoric sites documented along the paleochannel of the Hakra River (an ancient tributary of the Indus), spanning the Early Harappan phase (circa 4000–2600 BCE) to the Late Harappan (circa 1900–1300 BCE). These settlements, characterized by mud-brick structures, pottery, and agrarian remains, indicate a network of rural communities engaged in agriculture and trade, though no major urban center equivalent to Harappa or Mohenjo-daro has been identified directly at Uch itself.[13][14] Local traditions attribute Uch's founding to Alexander the Great in 325 BCE, positing it as the site of Alexandria on the Indus (Greek: Ἀλεξάνδρεια ἡ ἐν Ἰνδῷ), a garrison city established during his campaign along the river. This identification was tentatively advanced by 19th-century British archaeologist Alexander Cunningham based on toponymic and historical correlations, but lacks substantiation from contemporary Greek accounts or material artifacts such as Hellenistic coins or fortifications at the site.[8] Post-Indus periods saw the area's integration into broader South Asian polities, including the Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE) and subsequent Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, and Kushan (circa 30–375 CE) influences, with the latter promoting Buddhism across Punjab; however, specific references to Uch or excavations revealing Buddhist stupas, viharas, or inscriptions remain absent, suggesting it functioned primarily as a peripheral riverside settlement rather than a documented urban or religious hub prior to Islamic arrivals around the 8th century CE.[15]Early Islamic Period and Medieval Developments

Uch entered the Islamic era following its conquest by Muhammad ibn Qasim in 712 CE during the Umayyad Caliphate's expansion into Sindh, marking an early foothold for Muslim rule in the region.[8] Historical records from the period are sparse, with limited documentation on governance or cultural shifts in the subsequent centuries. By the early 11th century, the city, possibly known then as Bhatia, fell under the influence of Mahmud of Ghazni around 1006 CE, integrating it into broader Turkic-Islamic networks.[8] In the late 11th century, Uch emerged as a hub for Shi'ite Nizari Ismailis from around 1094 CE, evidenced by graves of Nizari and Musta'li Ismaili figures, reflecting sectarian diversity amid broader Sunni dominance in the subcontinent.[8] The Ghurid conquest under Muhammad of Ghor in 1175 CE further solidified Islamic administrative control. By the early 13th century, Nasir ad-Din Qabacha, appointed governor in 1204 CE, declared independence in 1211 CE and ruled Upper Sindh until 1228 CE, when Sultan Iltutmish of the Delhi Sultanate captured the city after conflicts involving Mongol threats and rival warlords.[8] This established Uch as an early stronghold of the Delhi Sultanate, facilitating military and administrative extensions into Punjab and Sindh. Medieval developments centered on religious and scholarly growth, with Uch serving as a refuge for Muslim scholars fleeing persecution elsewhere, evolving into a metropolitan center between the 12th and 17th centuries.[15] A pivotal figure was Sufi saint Jalaluddin Surkh-Posh Bukhari (1199–1291 CE), who migrated to Uch around 1244–1245 CE and founded a religious school alongside his son Baha' al-Halim, actively converting local tribes to Islam through missionary efforts.[16] Bukhari's lineage and teachings, rooted in Bukharan scholarly traditions, positioned Uch as a nucleus for Sufi propagation, with his shrine becoming a enduring symbol of the city's saintly heritage. By 1216 CE, local chroniclers in Uch had compiled Persian accounts of earlier conquests like bin Qasim's, underscoring the city's emerging role in Islamic historiography.[17] These foundations laid the groundwork for Uch's reputation as a "city of saints," with multiple Sufi lineages establishing tombs that attracted pilgrims and reinforced Islamic cultural dominance.[15]Mamluk and Sultanate Eras

Nasir ad-Din Qabacha, appointed governor of Uch by the Ghurids around 1205, extended control over Multan and parts of Sindh, establishing a semi-independent domain that overlapped with the early Mamluk dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1290).[18] His rule ended in 1227 when Sultan Iltutmish defeated him during a campaign along the Indus River, after which Qabacha drowned while fleeing; Uch was subsequently incorporated into the Delhi Sultanate and governed directly from the capital.[19][20] The Sufi saint Jalaluddin Surkh-Posh Bukhari, a proponent of the Suhrawardi order, settled permanently in Uch in 1244 CE, founding a khanqah that attracted disciples and elevated the city's status as a spiritual hub amid the consolidation of Sultanate authority.[21][19] Bukhari's presence facilitated the spread of Islamic mysticism, drawing migrants from Central Asia and integrating local populations into Sufi networks, with his death in 1291 CE marking the close of the Mamluk era.[22] Under the succeeding Khilji (1290–1320) and Tughlaq (1320–1414) dynasties, Uch retained strategic value as a frontier outpost for administering Sindh and countering regional threats, while its religious institutions flourished, solidifying its role in the Sultanate's cultural landscape.[9] The city's governors, appointed by Delhi, oversaw iqta assignments and military garrisons, contributing to the stabilization of Muslim governance in the Indus region despite periodic challenges from local dynasts.[19]Invasions by Mongols and Timurids

In the mid-13th century, Uch faced repeated Mongol incursions amid the broader Chagatai Khanate's raids into the Indus region. A notable invasion occurred in 1245–1246, when Mongol forces under the command of Möngke Khan, supported by local Hohar tribes, targeted the city, exploiting regional instability following earlier Khwarazmian disruptions.[8] This assault contributed to the migration of Sufi saint Jalaluddin Surkh-Posh Bukhari to Uch around 1244–1245, as defensive capabilities faltered.[8] The Mongols launched a final major raid on Uch in 1305, during the weakening of the Delhi Sultanate's peripheral control.[8] This event paved the way for administrative reconfiguration, with Uch falling under the governorship of Ghazi Baig, appointed by Ghiyas ud-Din Tughlaq, marking a transition toward firmer Tughlaq oversight and reducing immediate Mongol threats through fortified alliances.[8] Overall, these invasions eroded Uch's autonomy, depopulated areas through slaughter and enslavement, and shifted power dynamics, though the city's strategic Indus location preserved its role as a trade and religious hub. The Timurid era brought further upheaval in the late 14th century. In 1398, during Timur's invasion of the Delhi Sultanate, his grandson Pir Muhammad ibn Jahangir captured Uch, integrating it briefly into Timurid spheres of influence as part of campaigns that sacked Delhi and ravaged Punjab.[8] Pir Muhammad's forces likely imposed tribute and garrisoned the area, but sustained control proved elusive amid Timur's withdrawal to Samarkand. This conquest disrupted local governance under the declining Tughlaqs, fostering a power vacuum exploited by subsequent Afghan and Langah rulers, while underscoring Uch's vulnerability to Central Asian nomadic incursions.[8] The Timurid passage inflicted economic damage through plunder but did not lead to permanent demographic collapse, as Uch's shrine-based economy recovered under later patrons.Langah Sultanate Rule

The Langah Sultanate established control over Uch Sharif in the early 15th century as part of its dominion centered in Multan, extending across southern Punjab from approximately 1445 until the late 1520s.[23] Founded by Budhan Khan, who adopted the title Mahmud Shah Langah, the dynasty originated from Rajput converts to Islam and consolidated power after expelling previous rulers.[24] Uch, strategically located along the Indus River, served as an important administrative and religious outpost within this territory, benefiting from the sultanate's policies of settling Baloch tribes for military support along the Derajat frontier.[12] Under Sultan Husayn Langah I (r. 1469–1508), the sultanate reached its zenith, marked by territorial expansion and economic prosperity through trade and agriculture in the region.[23] This period coincided with heightened Sufi activity in Uch, where the Qadiriyya order gained prominence; Muhammad Ghaus Gilani, a descendant of Abdul Qadir Gilani, founded a khanqah in the mid-15th century, enhancing the city's role as a hub for Islamic mysticism.[12] Architectural developments, such as the 1493 tomb of Bibi Jawindi, reflect the era's patronage of religious structures, blending local and Persian influences in tilework and design. The Langahs maintained nominal suzerainty amid rivalries with the Delhi Sultanate and later Afghan Lodis, fostering a multicultural environment with Baloch migrations bolstering defenses. The sultanate's decline accelerated after Husayn's death, with internal strife and external pressures culminating in the Arghun invasion; Multan fell in 1528 to Shah Husayn, leading to Uch's integration into shifting powers before full Mughal absorption by 1530.[23] Despite political instability, the Langah era solidified Uch's enduring identity as a center of saint veneration, with enduring shrines attracting pilgrims and preserving the dynasty's legacy in local folklore and demographics.[25]Mughal Empire Integration

The Langah Sultanate, which had governed Uch as its capital since approximately 1445, lost autonomy in the early 16th century amid the establishment of Mughal dominance in northern India following Babur's victory at Panipat in 1526. However, the Langahs retained de facto independence into the 1540s, as evidenced by Shah Hussain Langah's refusal of refuge to the fugitive Humayun after his defeat by [Sher Shah Suri](/page/Sher Shah Suri).[26] Effective Mughal integration occurred under Akbar after his reconquest of the disrupted territories, with Multan and its dependencies—including Uch—brought under central control by the late 1550s, ending the interlude of Suri rule.[27] Uch was administratively subsumed into the Subah of Multan, one of Akbar's twelve imperial provinces formalized around 1580, placing it under Mughal-appointed governors responsible for revenue collection, law enforcement, and military obligations via the mansabdari system.[27] This structure imposed standardized land revenue assessments, drawing on Akbar's zabt system to measure cultivable land and fix taxes based on crop yields, which stabilized agrarian output in the fertile Indus valley environs of Uch despite periodic floods. The city's pre-existing role as a Sufi pilgrimage hub persisted, with Mughal patrons supporting shrine maintenance and expansions, reinforcing its cultural significance within the empire's network of religious endowments (waqfs).[28] Over two centuries of Mughal oversight, Uch contributed to the subah's economy through riverine trade in grains, textiles, and indigo, benefiting from imperial road links and security against nomadic raids.[27] Provincial governors, often from Persianized noble families, resided intermittently in Multan but extended oversight to Uch via local jagirdars, blending central directives with regional customs to minimize resistance. By the reign of Aurangzeb (1658–1707), however, weakening imperial cohesion allowed semi-autonomous tribal groups to erode direct control, presaging the subah's fragmentation.[27]Bahawalpur State Period

The Bahawalpur State, established by the Daudpotra rulers of the Abbasi dynasty in the mid-18th century following their migration from Sindh and conquests in the Cholistan region, incorporated Uch Sharif into its territory as a key settlement along strategic riverine routes. Nawab Bahawal Khan I (r. 1748–1750) and his successors expanded control over areas including Uch, utilizing it as a pathway for military campaigns, such as Bahawal Khan's reconquest of forts en route to reasserting dominance in the principality.[28] Under Daudpotra governance, Uch maintained its pre-existing role as a revered Sufi center, with shrines like those of Jalaluddin Bukhari and Bibi Jawindi serving as pilgrimage sites that bolstered the state's Islamic cultural identity, though no major new constructions are recorded from this era.[9] The principality formalized its autonomy through a subsidiary alliance with the British East India Company on February 22, 1833, under Nawab Fateh Muhammad Khan I (r. 1803–1837), granting Bahawalpur recognition as a princely state while ensuring British influence over foreign affairs and military matters. This arrangement provided administrative stability to peripheral towns like Uch, shielding them from external invasions that had plagued the region in prior centuries, and allowed the Nawabs to focus on internal revenue collection from agriculture and trade along the Sutlej and Indus rivers. Successive rulers, including Nawab Mohammad Bahawal Khan III (r. 1837–1866), who expanded irrigation works, indirectly supported Uch's agrarian economy, though the city itself remained more oriented toward religious endowments (waqfs) managed by hereditary custodians (sajjada nashins) rather than state-driven development.[28] Facing the partition of British India, Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan V (r. 1907–1966) acceded the Bahawalpur State to the Dominion of Pakistan on October 7, 1947, aligning with Muhammad Ali Jinnah's vision for Muslim-majority princely states. Uch Sharif, as part of the state's southern districts, transitioned seamlessly into Pakistani sovereignty, retaining its status as a tehsil headquarters. The Nawab's continued autonomy until the state's merger into West Pakistan on October 14, 1955, marked the end of princely rule, after which Uch fell under provincial administration amid broader national integration efforts, though its monuments faced increasing neglect post-independence.[28][9]Partition, Independence, and Contemporary History

Uch, as part of the princely state of Bahawalpur, acceded to the Dominion of Pakistan on October 7, 1947, shortly after the partition of British India on August 14–15, 1947. Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan V Bahadur, the ruler of Bahawalpur, signed the instrument of accession, making it one of the first princely states to formally join Pakistan and avoiding the prolonged negotiations faced by other rulers.[29] [30] This integration occurred amid widespread communal violence and mass migrations across Punjab and Bengal, but Bahawalpur's inland location and decisive pro-Pakistan stance by its Muslim-majority leadership resulted in relatively limited direct conflict within the state.[31] Following independence, Bahawalpur State maintained semi-autonomous status under the nawab until October 1955, when it was merged into the One Unit system as part of West Pakistan, effectively dissolving its separate administrative identity.[32] The dissolution of One Unit in 1970 integrated the region, including Uch, fully into Punjab province, aligning it with Pakistan's federal structure. Throughout this period, Uch remained a small, shrine-centered settlement with minimal industrial development, preserving its historical character amid national efforts to consolidate post-partition governance. In contemporary history, Uch Sharif has undergone steady population growth driven by regional urbanization and agricultural expansion in southern Punjab. The 1998 census recorded an urban population of 20,476, which increased to 42,684 by the 2017 census, reflecting an annual growth rate of approximately 3.93% in the preceding decade.[33] [34] Preliminary 2023 census data indicate further expansion to 98,852 residents, accompanied by land-use shifts from agricultural to residential areas.[35] Modern challenges include the encroachment of contemporary concrete structures on traditional vernacular architecture, prompting critiques of unsustainable building practices that erode cultural heritage.[36] Heritage preservation has emerged as a key focus, with international and national initiatives targeting the town's medieval monuments. The World Monuments Fund has supported conservation of the Uch Monument Complex, emphasizing stabilization of structures vulnerable to environmental degradation.[37] In March 2025, the Walled City of Lahore Authority launched projects to restore seven major shrines, including those of Jalal-ud-Din Surkh-Posh Bukhari and Makhdoom Jahania Jahangasht, addressing issues like structural decay and tilework deterioration.[38] These efforts underscore Uch's role as a living Sufi heritage site, balancing tourism potential with the need to mitigate urban pressures on its historical fabric.Geography

Location, Topography, and Environmental Setting

Uch Sharif is situated in Bahawalpur District in the southern part of Punjab province, Pakistan, approximately 75 kilometers southwest of Bahawalpur city.[39] The town occupies coordinates around 29°14′N 71°03′E and lies within the alluvial plains of the Indus River basin.[40] Historically, Uch was positioned at the confluence of the Indus and Chenab rivers, a strategic location that facilitated trade and settlement; however, avulsions in the river courses have shifted this confluence eastward to Mithankot, now about 100 kilometers distant.[41] The topography surrounding Uch Sharif consists of flat, low-lying plains typical of the Punjab region, with elevations generally between 100 and 120 meters above sea level. The landscape is dominated by depositional soils from the Indus system, including fertile clayey loam in cultivated areas, which support agriculture amid otherwise challenging conditions.[42] [43] Environmentally, the area features a subtropical desert climate marked by extreme aridity, sparse natural vegetation, and reliance on irrigation canals derived from the Indus for sustenance. Positioned on the western margins of the Cholistan Desert, Uch experiences hot, dry summers, cooler winters, and infrequent rainfall, contributing to soil salinity and desertification risks in unirrigated zones.[44] [42]Climate Patterns and Seasonal Variations

Uch, situated in the southern Punjab plain near the Indus River, experiences a hot desert climate characterized by extreme seasonal temperature variations, low humidity outside the summer monsoon period, and minimal annual precipitation averaging 143–223 mm. This arid environment results in prolonged dry spells interrupted briefly by monsoon influences, with the majority of rainfall—typically 50–70% of the yearly total—occurring between July and September, though even these amounts rarely exceed 50 mm per month in the region. Winters are mild and dry, while summers bring intense heat, often exacerbated by dust storms (locally known as loo winds) from April to June, which can push daytime temperatures above 45°C.[45][46][47] The hot season spans April to August, with average highs exceeding 37°C and peaking in June at around 41°C (105°F), accompanied by lows rarely dropping below 29°C (84°F); this period features mostly clear skies and low precipitation, fostering high evaporation rates that contribute to the area's desertification risks. In contrast, the cool season from December to February sees average highs of about 21°C (69°F) and lows near 7°C (45°F), with negligible rainfall (often under 5 mm monthly) and occasional fog, providing relief from the summer extremes but still maintaining dry conditions overall. Transitional spring (March–April) and autumn (October–November) periods exhibit moderate temperatures (highs 28–35°C) and slightly higher humidity near the river, though precipitation remains sparse, with November being the driest month at approximately 2.5 mm.[47][48] These patterns align with broader southern Punjab trends, where the proximity to the Cholistan Desert amplifies aridity, and monsoon variability can lead to occasional flooding along the Indus, as observed in events like the 2010 deluge that affected nearby Bahawalpur district with over 200 mm in a single season. Long-term data indicate gradual warming, with summer highs increasing by 1–2°C since the 1980s, consistent with regional climate shifts driven by greenhouse gas accumulation rather than localized factors alone.[49][50]Urban Morphology and Infrastructure

Uch Sharif's urban morphology reflects its evolution as a historic settlement on elevated mounds, with the core divided into distinct sections including Uch Bukhari to the north on the highest mound (approximately 15 meters above surrounding fields) and Uch Gilani to the south on a lower, centrally elevated terrain that slopes outward.[51] These mounds, remnants of ancient layering, contribute to a compact, organic layout shaped by natural topography and historical constraints, featuring irregular street patterns: primary wide streets for vehicular access, secondary narrower lanes serving residential areas, tertiary connectors, and numerous close-ended dead-end paths typical of pre-modern Islamic urban planning.[51] The historic fabric remains largely intact, centered around shrines and tombs constructed from local sandstone and glazed tiles, with the traditional Chunnri Bazaar occupying about 12 acres as the primary commercial spine linking the divided sections via kucha (unpaved or semi-paved) shops.[51] Minor mohallas, such as Khawajgan and Sodhgaon below Uch Bukhari, extend this pattern, preserving a dense, pedestrian-oriented environment amid ongoing pressures from modern encroachments. Contemporary expansions exhibit unplanned sprawl, particularly around the shrinking mela ground that once separated Uch Bukhari and Uch Gilani, leading to fragmented land use and the replacement of traditional structures with generic residential buildings that disrupt the cohesive historic silhouette.[52] This growth, driven by population increases from 8,491 in 1972 to higher recent figures, has extended beyond the mound cores into peripheral agricultural lands, resulting in ad-hoc developments lacking integrated zoning or preservation buffers around monuments.[33] Infrastructure lags behind, with reliance on groundwater for domestic use in areas like Mohalla Bukhari due to the absence of comprehensive piped water systems, exacerbating vulnerabilities in this arid region.[53] Road networks include ongoing upgrades, such as the dualization of the 30-kilometer Uch Sharif to Ahmedpur Sharqia road to improve connectivity to Bahawalpur (about 50 km east), addressing bottlenecks in the primary access routes.[54] Electricity and sanitation remain basic, with public facilities often deficient, as evidenced by infrastructure shortfalls in local institutions, though provincial development plans aim to integrate solar and piped enhancements in select zones.[55] These efforts, however, contend with the challenges of balancing heritage conservation against incremental urbanization in a small city whose morphology prioritizes spiritual and communal nodes over expansive modern grids.[51]Demographics

Population Growth and Census Data

The population of Uch Sharif has exhibited consistent growth since Pakistan's independence, accelerating notably in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as documented in national census records. Early post-partition figures placed the town's residents at approximately 4,170 in the 1951 census, reflecting a modest base amid regional integration into the new state. Subsequent censuses indicate steady expansion: 5,483 in 1961, 8,491 in 1972, and 13,386 in 1981, driven by natural increase and limited rural-to-urban migration in Punjab's southern districts. By the 1998 census, the population had risen to 20,476, roughly doubling from 1981 levels over 17 years. The 2017 census recorded 42,684 inhabitants, continuing the upward trajectory with an implied average annual growth rate of about 3.7% from 1998.[35] The most recent 2023 census reported a sharp increase to 98,852, with 50,041 males and 48,800 females, yielding an average annual growth rate of 15.07% over the intervening six years and an average household size of 7.15 persons.[1]| Census Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1951 | 4,170 |

| 1961 | 5,483 |

| 1972 | 8,491 |

| 1981 | 13,386 |

| 1998 | 20,476 |

| 2017 | 42,684 |

| 2023 | 98,852 |