Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

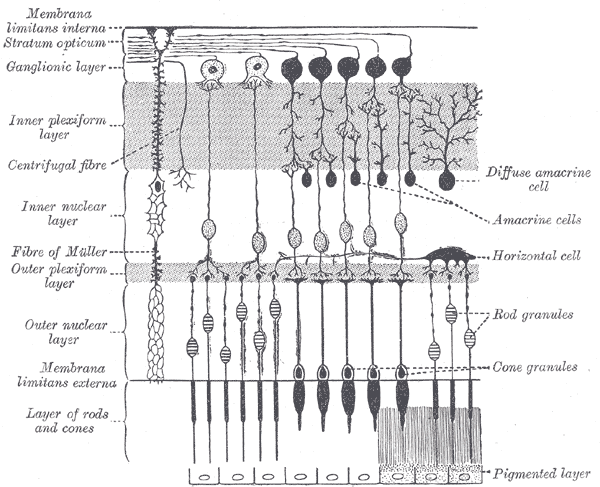

Retina horizontal cell

View on Wikipedia| Horizontal cell | |

|---|---|

Plan of retinal neurons. | |

| Details | |

| System | Visual system |

| Location | Retina |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D051248 |

| NeuroLex ID | nifext_40 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Horizontal cells are the laterally interconnecting neurons having cell bodies in the inner nuclear layer of the retina of vertebrate eyes. They help integrate and regulate the input from multiple photoreceptor cells. Among their functions, horizontal cells are believed to be responsible for increasing contrast via lateral inhibition and adapting both to bright and dim light conditions. Horizontal cells provide inhibitory feedback to rod and cone photoreceptors.[1][2] They are thought to be important for the antagonistic center-surround property of the receptive fields of many types of retinal ganglion cells.[3]

Other retinal neurons include photoreceptor cells, bipolar cells, amacrine cells, and retinal ganglion cells.

Structure

[edit]Depending on the species, there are typically one or two classes of horizontal cells, with a third type sometimes proposed.[1][2]

Horizontal cells span across photoreceptors and summate inputs before synapsing onto photoreceptor cells.[1][2] Horizontal cells may also synapse onto bipolar cells, but this remains uncertain.[1][4]

There is a greater density of horizontal cells towards the central region of the retina. In the cat, it is observed that A-type horizontal cells have a density of 225 cells/mm2 near the center of the retina and a density of 120 cells/mm2 in more peripheral retina.[5]

Horizontal cells and other retinal interneuron cells are less likely to be near neighbours of the same subtype than would occur by chance, resulting in 'exclusion zones' that separate them. Mosaic arrangements provide a mechanism to distribute each cell type evenly across the retina, ensuring that all parts of the visual field have access to a full set of processing elements.[5] MEGF10 and MEGF11 transmembrane proteins have critical roles in the formation of the mosaics by horizontal cells and starburst amacrine cells in mice.[6]

Function

[edit]Horizontal cells are depolarized by the release of glutamate from photoreceptors, which happens in the absence of light. Depolarization of a horizontal cell causes it to hyperpolarize nearby photoreceptors. Conversely, in the light, a photoreceptor releases less glutamate, which hyperpolarizes the horizontal cell, leading to depolarization of nearby photoreceptors. Thus, horizontal cells provide negative feedback to photoreceptors. The moderately wide lateral spread and coupling of horizontal cells by gap junctions, measures the average level of illumination falling upon a region of the retinal surface, which horizontal cells then subtract a proportionate value from the output of photoreceptors to hold the signal input to the inner retinal circuitry within its operating range.[1] Horizontal cells are also one of two groups of inhibitory interneurons that contribute to the surround of retinal ganglion cells:[2]

Illumination Center photoreceptor hyperpolarization Horizontal cell hyperpolarization Surround photoreceptor depolarization

The exact mechanism by which depolarization of horizontal cells hyperpolarizes photoreceptors is uncertain. Although horizontal cells contain GABA, the main mechanisms by which horizontal cells inhibit cones probably do not involve the release of GABA by horizontal cells onto cones.[4][7][8] Two mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive likely contribute to horizontal cell inhibition of glutamate release by cones. Both postulated mechanisms depend on the protected environment provided by the invaginating synapses that horizontal cells make onto cones.[4][9] The first postulated mechanism is a very fast ephaptic mechanism that has no synaptic delay, making it one of the fastest inhibitory synapses known.[4][10][11] The second postulated mechanism is relatively slow with a time constant of about 200 ms and depends on ATP release via Pannexin 1 channels located on horizontal cell dendrites invaginating the cone synaptic terminal. The ecto-ATPase NTPDase1 hydrolyses extracellular ATP to AMP, phosphate groups, and protons. The phosphate groups and protons form a pH buffer with a pKa of 7.2, which keeps the pH in the synaptic cleft relatively acidic. This inhibits the cone Ca2+ channels and consequently reduces the glutamate release by the cones.[4][11][12][13][14]

The center-surround antagonism of bipolar cells is thought to be inherited from cones. However, when recordings are made from parts of the cone that are distant from the cone terminals that synapse onto bipolar cells, center-surround antagonism seems to be less reliable in cones than in bipolar cells. As the invaginating synapses from horizontal cells are made onto cone terminals, the center-surround antagonism of cones is thought to be more reliably present in cone terminals.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Masland, RH (2012). "The neuronal organization of the retina". Neuron. 76 (2): 266–280. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.002. PMC 3714606. PMID 23083731.

- ^ a b c d Demb JB, Singer JH (November 2015). "Functional Circuitry of the Retina". Annu Rev Vis Sci. 1: 263–289. doi:10.1146/annurev-vision-082114-035334. PMC 5749398. PMID 28532365.

- ^ Chaya, Taro; Matsumoto, Akihiro; Sugita, Yuko; Watanabe, Satoshi; Kuwahara, Ryusuke; Tachibana, Masao; Furukawa, Takahisa (2017-07-17). "Versatile functional roles of horizontal cells in the retinal circuit". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 5540. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.5540C. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05543-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5514144. PMID 28717219.

- ^ a b c d e Thoreson WB, Mangel SC (September 2012). "Lateral interactions in the outer retina". Prog Retin Eye Res. 31 (5): 407–41. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.04.003. PMC 3401171. PMID 22580106.

- ^ a b Wässle H, Riemann HJ (March 1978). "The mosaic of nerve cells in the mammalian retina". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 200 (1141): 441–61. Bibcode:1978RSPSB.200..441W. doi:10.1098/rspb.1978.0026. PMID 26058. S2CID 28724457.

- ^ Kay, JN; Chu, MW; Sanes, JR (2012). "MEGF10 and MEGF11 mediate homotypic interactions required for mosaic spacing of retinal neurons". Nature. 483 (7390): 465–9. Bibcode:2012Natur.483..465K. doi:10.1038/nature10877. PMC 3310952. PMID 22407321.

- ^ Verweij J, Kamermans M, Spekreijse H (December 1996). "Horizontal cells feed back to cones by shifting the cone calcium-current activation range". Vision Res. 36 (24): 3943–53. doi:10.1016/S0042-6989(96)00142-3. PMID 9068848.

- ^ Verweij J, Hornstein EP, Schnapf JL (November 2003). "Surround antagonism in macaque cone photoreceptors". J. Neurosci. 23 (32): 10249–57. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10249.2003. PMC 6741006. PMID 14614083.

- ^ Barnes S (Dec 2003). "Center-surround antagonism mediated by proton signaling at the cone photoreceptor synapse". J Gen Physiol. 122 (6): 653–6. doi:10.1085/jgp.200308947. PMC 2229589. PMID 14610023.

- ^ Kamermans M, Fahrenfort I, Schultz K, Janssen-Bienhold U, Sjoerdsma T, Weiler R (May 2001). "Hemichannel-mediated inhibition in the outer retina". Science. 292 (5519): 1178–80. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1178K. doi:10.1126/science.1060101. PMID 11349152. S2CID 20660565.

- ^ a b Vroman R, Klaassen LJ, Howlett MH, Cenedese V, Klooster J, Sjoerdsma T, Kamermans M (May 2014). "Extracellular ATP hydrolysis inhibits synaptic transmission by increasing ph buffering in the synaptic cleft". PLOS Biol. 12 (5) e1001864. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001864. PMC 4028192. PMID 24844296.

- ^ Hirasawa H, Kaneko A (December 2003). "pH changes in the invaginating synaptic cleft mediate feedback from horizontal cells to cone photoreceptors by modulating Ca2+ channels". J. Gen. Physiol. 122 (6): 657–71. doi:10.1085/jgp.200308863. PMC 2229595. PMID 14610018.

- ^ Vessey JP, Stratis AK, Daniels BA, Da Silva N, Jonz MG, Lalonde MR, Baldridge WH, Barnes S (April 2005). "Proton-mediated feedback inhibition of presynaptic calcium channels at the cone photoreceptor synapse". J. Neurosci. 25 (16): 4108–17. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5253-04.2005. PMC 6724943. PMID 15843613.

- ^ Davenport CM, Detwiler PB, Dacey DM (January 2008). "Effects of pH buffering on horizontal and ganglion cell light responses in primate retina: evidence for the proton hypothesis of surround formation". J. Neurosci. 28 (2): 456–64. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2735-07.2008. PMC 3057190. PMID 18184788.

- ^ Byzov AL, Shura-Bura TM (1986). "Electrical feedback mechanism in the processing of signals in the outer plexiform layer of the retina". Vision Res. 26 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(86)90069-6. PMID 3012877. S2CID 21785150.

Bibliography

[edit]- Masland, RH (2012). "The neuronal organization of the retina". Neuron. 76 (2): 266–280. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.002. PMC 3714606. PMID 23083731.