Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pannexin

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Purinergic signalling |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

| Membrane transporters |

| Pannexin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | Pannexin | ||||||

| InterPro | IPR039099 | ||||||

| TCDB | 1.A.25 | ||||||

| |||||||

| pannexin 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | PANX1 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 24145 | ||||||

| HGNC | 8599 | ||||||

| OMIM | 608420 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_015368 | ||||||

| UniProt | Q96RD7 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 11 q14-q21 | ||||||

| |||||||

| pannexin 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | PANX2 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 56666 | ||||||

| HGNC | 8600 | ||||||

| OMIM | 608421 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_052839 | ||||||

| UniProt | Q96RD6 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 22 q13 | ||||||

| |||||||

| pannexin 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | PANX3 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 116337 | ||||||

| HGNC | 20573 | ||||||

| OMIM | 608422 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_052959 | ||||||

| UniProt | Q96QZ0 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 11 q24.2 | ||||||

| |||||||

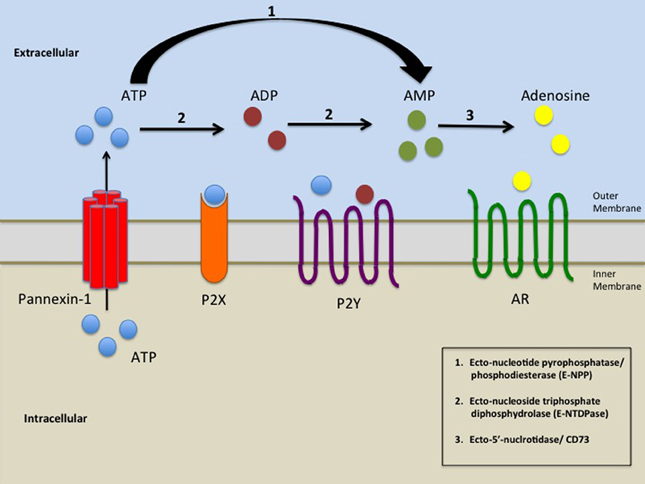

Pannexins (from Greek 'παν' — all, and from Latin 'nexus' — connection) are a family of vertebrate proteins identified by their homology to the invertebrate innexins.[1] While innexins are responsible for forming gap junctions in invertebrates, the pannexins have been shown to predominantly exist as large transmembrane channels connecting the intracellular and extracellular space, allowing the passage of ions and small molecules between these compartments (such as ATP and sulforhodamine B).

Three pannexins have been described in Chordates: Panx1, Panx2 and Panx3.[2]

Function

[edit]Pannexins can form nonjunctional transmembrane channels for transport of molecules of less than 1000 Da. These hemichannels can be present in plasma, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi membranes. They transport Ca2+, ATP, inositol triphosphate and other small molecules and can form hemichannels with greater ease than connexin subunits.[3] Pannexin 1 and pannexin 2 underlie channel function in neurons and contribute to ischemic brain damage.[4]

Pannexin 1 has been shown to be involved in early stages of innate immunity through an interaction with the P2X7 purinergic receptor. Activation of the pannexin channel through binding of ATP to P2X7 receptor leads to the release of interleukin-1β.[5]

Hypothetical roles of pannexins in the nervous system include participating in sensory processing, synchronization between hippocampus and cortex, hippocampal plasticity, and propagation of calcium waves. Calcium waves are supported by glial cells, which help maintain and modulate neuronal metabolism. According to one of the hypotheses, pannexins also may participate in pathological reactions, including the neural damage after ischemia and subsequent cell death.[6]

Pannexin 1 channels are pathways for release of ATP from cells.[7]

Relationship to connexins

[edit]Intercellular gap junctions in vertebrates, including humans, are formed by the connexin family of proteins.[8] Structurally, pannexins and connexins are very similar, consisting of 4 transmembrane domains, 2 extracellular and 1 intracellular loop, along with intracellular N- and C-terminal tails. Despite this shared topology, the protein families do not share enough sequence similarity to confidently infer common ancestry.

The N-terminal portion (Pfam PF12534) of VRAC-forming LRRC8 proteins like LRRC8A may also be related to pannexins.[9]

The structure of a Xenopus tropicalis (western clawed frog) pannexin (PDB: 6VD7) has been solved. It forms a heptameric disc. The human version (PDB: 6M02) is similar.[10][11]

Clinical significance

[edit]Truncating mutations in pannexin 1 have been shown to promote breast and colon cancer metastasis to the lungs by allowing cancer cells to survive mechanical stretch in the microcirculation through the release of ATP.[12]

Pannexins may be involved in the process of tumor development. Particularly, PANX2 expression levels predict post diagnosis survival for patients with glial tumors.

Probenecid, a well-established drug for the treatment of gout, allows for discrimination between channels formed by connexins and pannexins. Probenecid does not affect channels formed by connexins, but it inhibits pannexin-1 channels.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Panchin Y, Kelmanson I, Matz M, Lukyanov K, Usman N, Lukyanov S (June 2000). "A ubiquitous family of putative gap junction molecules". Current Biology. 10 (13): R473-4. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.R473P. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00576-5. PMID 10898987. S2CID 20001454.

- ^ Litvin O, Tiunova A, Connell-Alberts Y, Panchin Y, Baranova A (2006). "What is hidden in the pannexin treasure trove: the sneak peek and the guesswork". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 10 (3): 613–34. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00424.x. PMC 3933146. PMID 16989724.

- ^ Shestopalov VI, Panchin Y (February 2008). "Pannexins and gap junction protein diversity". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (3): 376–94. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7200-1. PMC 11131650. PMID 17982731. S2CID 23181471.

- ^ Bargiotas P, Krenz A, Hormuzdi SG, Ridder DA, Herb A, Barakat W, et al. (December 2011). "Pannexins in ischemia-induced neurodegeneration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (51): 20772–7. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820772B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018262108. PMC 3251101. PMID 22147915.

- ^ Pelegrin P, Surprenant A (November 2006). "Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor". The EMBO Journal. 25 (21): 5071–82. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. PMC 1630421. PMID 17036048.

- ^ Bargiotas P, Krenz A, Hormuzdi SG, Ridder DA, Herb A, Barakat W, et al. (December 2011). "Pannexins in ischemia-induced neurodegeneration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (51): 20772–7. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820772B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018262108. PMC 3251101. PMID 22147915.

- ^ Bao L, Locovei S, Dahl G (August 2004). "Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP". FEBS Letters. 572 (1–3): 65–8. Bibcode:2004FEBSL.572...65B. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.009. PMID 15304325. S2CID 43459258.

- ^ Dahl G, Locovei S (July 2006). "Pannexin: to gap or not to gap, is that a question?". IUBMB Life. 58 (7): 409–19. doi:10.1080/15216540600794526. PMID 16801216. S2CID 24038607.

- ^ Abascal F, Zardoya R (July 2012). "LRRC8 proteins share a common ancestor with pannexins, and may form hexameric channels involved in cell-cell communication". BioEssays. 34 (7): 551–60. doi:10.1002/bies.201100173. hdl:10261/124027. PMID 22532330. S2CID 24648128.

- ^ Michalski K, Syrjanen JL, Henze E, Kumpf J, Furukawa H, Kawate T (February 2020). "The cryo-EM structure of a pannexin 1 reveals unique motifs for ion selection and inhibition". eLife. 9 e54670. doi:10.7554/eLife.54670. PMC 7108861. PMID 32048993.

- ^ Qu R, Dong L, Zhang J, Yu X, Wang L, Zhu S (March 2020). "Cryo-EM structure of human heptameric Pannexin 1 channel". Cell Research. 30 (5): 446–448. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0298-5. PMC 7196123. PMID 32203128.

- ^ Furlow PW, Zhang S, Soong TD, Halberg N, Goodarzi H, Mangrum C, et al. (July 2015). "Mechanosensitive pannexin-1 channels mediate microvascular metastatic cell survival". Nature Cell Biology. 17 (7): 943–52. doi:10.1038/ncb3194. PMC 5310712. PMID 26098574.

- ^ Silverman W, Locovei S, Dahl G (September 2008). "Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 295 (3): C761-7. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00227.2008. PMC 2544448. PMID 18596212.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrew L Harris, Darren Locke (2009). Connexins, A Guide. New York: Springer. p. 574. ISBN 978-1-934115-46-6.