Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ciliary muscle

View on Wikipedia| Ciliary muscle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | UK: /ˈsɪliəri/, US: /ˈsɪliɛri/[2] |

| Origin | 1) longitudinal fibers → scleral spur; 2) circular fibers → encircle root of iris[1] |

| Insertion | 1) longitudinal fibers → ciliary process, 2) circular fibers → encircle root of iris[1] |

| Artery | Long posterior ciliary arteries |

| Vein | Vorticose veins |

| Nerve | Short ciliary Parasympathetic fibers in the oculomotor nerve (CN-III) synapse in the ciliary ganglion. Parasympathetic postganglionic fibers from the ciliary ganglion travel through short ciliary nerves into the ocular globe. |

| Actions | 1) Accommodation, 2) regulation of trabecular meshwork pore sizes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus ciliaris |

| TA98 | A15.2.03.014 |

| TA2 | 6770 |

| FMA | 49151 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The ciliary muscle is an intrinsic muscle of the eye formed as a ring of smooth muscle[3][4] in the eye's middle layer, the uvea (vascular layer). It controls accommodation for viewing objects at varying distances and regulates the flow of aqueous humor into Schlemm's canal. It also changes the shape of the lens within the eye but not the size of the pupil[5] which is carried out by the sphincter pupillae muscle and dilator pupillae.

The ciliary muscle, pupillary sphincter muscle and pupillary dilator muscle sometimes are called intrinsic ocular muscles[6] or intraocular muscles.[7]

Structure

[edit]Development

[edit]The ciliary muscle develops from mesenchyme within the choroid and is considered a cranial neural crest derivative.[8]

Nerve supply

[edit]

The ciliary muscle receives parasympathetic fibers from the short ciliary nerves that arise from the ciliary ganglion. The parasympathetic postganglionic fibers are part of cranial nerve V1 (Nasociliary nerve of the trigeminal), while presynaptic parasympathetic fibers to the ciliary ganglia travel with the oculomotor nerve.[9] The postganglionic parasympathetic innervation arises from the ciliary ganglion.[10]

Presynaptic parasympathetic signals that originate in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus are carried by cranial nerve III (the oculomotor nerve) and travel through the ciliary ganglion via the postganglionic parasympathetic fibers which travel in the short ciliary nerves and supply the ciliary body and iris. Parasympathetic activation of the M3 muscarinic receptors causes ciliary muscle contraction. The effect of contraction is to decrease the diameter of the ring of ciliary muscle causing relaxation of the zonule fibers, the lens becomes more spherical, increasing its power to refract light for near vision.[citation needed]

The parasympathetic tone is dominant when a higher degree of accommodation of the lens is required, such as reading a book.[11]

Function

[edit]Accommodation

[edit]The ciliary fibers have circular (Ivanoff),[12] longitudinal (meridional) and radial orientations.[13]

According to Hermann von Helmholtz's theory, the circular ciliary muscle fibers affect zonular fibers in the eye (fibers that suspend the lens in position during accommodation), enabling changes in lens shape for light focusing. When the ciliary muscle contracts, it pulls itself forward and moves the frontal region toward the axis of the eye. This releases the tension on the lens caused by the zonular fibers (fibers that hold or flatten the lens). This release of tension of the zonular fibers causes the lens to become more spherical, adapting to short range focus. Conversely, relaxation of the ciliary muscle causes the zonular fibers to become taut, flattening the lens, increasing the focal distance,[14] increasing long range focus. Although Helmholtz's theory has been widely accepted since 1855, its mechanism still remains controversial. Alternative theories of accommodation have been proposed by others, including L. Johnson, M. Tscherning, and especially Ronald A. Schachar.[3]

Trabecular meshwork pore size

[edit]Contraction and relaxation of the longitudinal fibers, which insert into the trabecular meshwork in the anterior chamber of the eye, cause an increase and decrease in the meshwork pore size, respectively, facilitating and impeding aqueous humour flow into the canal of Schlemm.[15]

Clinical significance

[edit]Glaucoma

[edit]Open-angle glaucoma (OAG) and closed-angle glaucoma (CAG) may be treated by muscarinic receptor agonists (e.g., pilocarpine), which cause rapid miosis and contraction of the ciliary muscles, opening the trabecular meshwork, facilitating drainage of the aqueous humour into the canal of Schlemm and ultimately decreasing intraocular pressure.[16]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The word ciliary had its origins around 1685–1695.[17] The term cilia originated a few years later in 1705–1715, and is the Neo-Latin plural of cilium meaning eyelash. In Latin, cilia means upper eyelid and is perhaps a back formation from supercilium, meaning eyebrow. The suffix -ary originally occurred in loanwords from Middle English (-arie), Old French (-er, -eer, -ier, -aire, -er), and Latin (-ārius); it can generally mean "pertaining to, connected with", "contributing to", and "for the purpose of".[18] Taken together, cili(a)-ary pertains to various anatomical structures in and around the eye, namely the ciliary body and annular suspension of the lens of the eye.[19]

Additional images

[edit]-

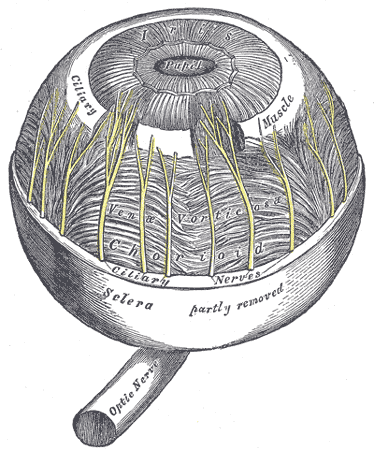

The arteries of the choroid and iris. The greater part of the sclera has been removed.

-

Iris, front view.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Gest, Thomas R; Burkel, William E. "Anatomy Tables - Eye." Medical Gross Anatomy. 2000. University of Michigan Medical School. January 5, 2010 Umich.edu Archived 2010-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b Kleinmann, G; Kim, H. J.; Yee, R. W. (2006). "Scleral expansion procedure for the correction of presbyopia". International Ophthalmology Clinics. 46 (3): 1–12. doi:10.1097/00004397-200604630-00003. PMID 16929221. S2CID 45247729.

- ^ Schachar, Ronald A. (2012). "Anatomy and Physiology." (Chapter 4) The Mechanism of Accommodation and Presbyopia. Kugler Publications. ISBN 978-9-062-99233-1.

- ^ Land, Michael (Apr 19, 2015). "Focusing by shape change in the lens of the eye: a commentary on Young (1801) 'On the mechanism of the eye'". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 370 (1666) 20140308. School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0308. PMC 4360117. PMID 25750232.

- ^ Kels, Barry D.; Grzybowski, Andrzej; Grant-Kels, Jane M. (March 2015). "Human ocular anatomy". Clinics in Dermatology. 33 (2): 140–146. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.10.006. PMID 25704934.

- ^ Ludwig, Parker E.; Aslam, Sanah; Czyz, Craig N. (2024). "Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Muscles". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29262013.

- ^ Dudek, Ronald W. (2010-04-01). Embryology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-60547-901-9.

- ^ Moore KL, Dalley AF (2006). "Head (chapter 7)". Clinically Oriented Anatomy (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 972. ISBN 0-7817-3639-0.

- ^ McDougal, David H.; Gamlin, Paul D. (January 2015). "Autonomic control of the eye". Comprehensive Physiology. 5 (1): 439–473. doi:10.1002/cphy.c140014. PMC 4919817. PMID 25589275.

- ^ Brunton, L. L.; Chabner, Bruce; Knollmann, Björn C., eds. (2011). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ "Ocular Embryology with Special Reference to Chamber Angle Development". The Glaucomas. 2009. pp. 61–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69146-4_8. ISBN 978-3-540-69144-0.

- ^ Riordan-Eva Paul, "Chapter 1. Anatomy & Embryology of the Eye" (Chapter). Riordan-Eva P, Whitcher JP (2008). Vaughan & Asbury's General Ophthalmology (17th ed.). McGraw-Hill. AccessMedicine.com Archived 2009-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brunton, Laurence L.; Lazo, John S.; Parker, Keith, eds. (2005). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ Salmon John F, "Chapter 11. Glaucoma" (Chapter). Riordan-Eva P, Whitcher JP (2008). Vaughan & Asbury's General Ophthalmology (17th ed.). McGraw-Hill. AccessMedicine.com Archived 2009-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Le, Tao T.; Cai, Xumei; Waples-Trefil, Flora. "QID: 22067". USMLERx. MedIQ Learning, LLC. 2006–2010. 13 January 2010 Usmlerx.com Archived 2012-10-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "cilia", Unabridged. Source location: Random House, Inc. Reference.com. Retrieved on 2010-01-16 from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/cilia.

- ^ Dictionary.com, "-ary", in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Source location: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Reference.com. Retrieved on 2010-01-16 from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/-ary.

- ^ "ciliary," in Dictionary.com Unabridged. Source location: Random House, Inc. Reference.com. Retrieved on 2010-01-16 from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/ciliary.

External links

[edit]- Lens, zonule fibers, and ciliary muscles—SEM Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine