Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Information model

View on Wikipedia

An information model in software engineering is a representation of concepts and the relationships, constraints, rules, and operations to specify data semantics for a chosen domain of discourse. Typically it specifies relations between kinds of things, but may also include relations with individual things. It can provide sharable, stable, and organized structure of information requirements or knowledge for the domain context.[1]

Overview

[edit]The term information model in general is used for models of individual things, such as facilities, buildings, process plants, etc. In those cases, the concept is specialised to facility information model, building information model, plant information model, etc. Such an information model is an integration of a model of the facility with the data and documents about the facility.

Within the field of software engineering and data modeling, an information model is usually an abstract, formal representation of entity types that may include their properties, relationships and the operations that can be performed on them. The entity types in the model may be kinds of real-world objects, such as devices in a network, or occurrences, or they may themselves be abstract, such as for the entities used in a billing system. Typically, they are used to model a constrained domain that can be described by a closed set of entity types, properties, relationships and operations.

An information model provides formalism to the description of a problem domain without constraining how that description is mapped to an actual implementation in software. There may be many mappings of the information model. Such mappings are called data models, irrespective of whether they are object models (e.g. using UML), entity relationship models or XML schemas.

Information modeling languages

[edit]

In 1976, an entity-relationship (ER) graphic notation was introduced by Peter Chen. He stressed that it was a "semantic" modelling technique and independent of any database modelling techniques such as Hierarchical, CODASYL, Relational etc.[2] Since then, languages for information models have continued to evolve. Some examples are the Integrated Definition Language 1 Extended (IDEF1X), the EXPRESS language and the Unified Modeling Language (UML).[1]

Research by contemporaries of Peter Chen such as J.R.Abrial (1974) and G.M Nijssen (1976) led to today's Fact Oriented Modeling (FOM) languages which are based on linguistic propositions rather than on "entities". FOM tools can be used to generate an ER model which means that the modeler can avoid the time-consuming and error prone practice of manual normalization. Object-Role Modeling language (ORM) and Fully Communication Oriented Information Modeling (FCO-IM) are both research results developed in the early 1990s, based upon earlier research.

In the 1980s there were several approaches to extend Chen’s Entity Relationship Model. Also important in this decade is REMORA by Colette Rolland.[3]

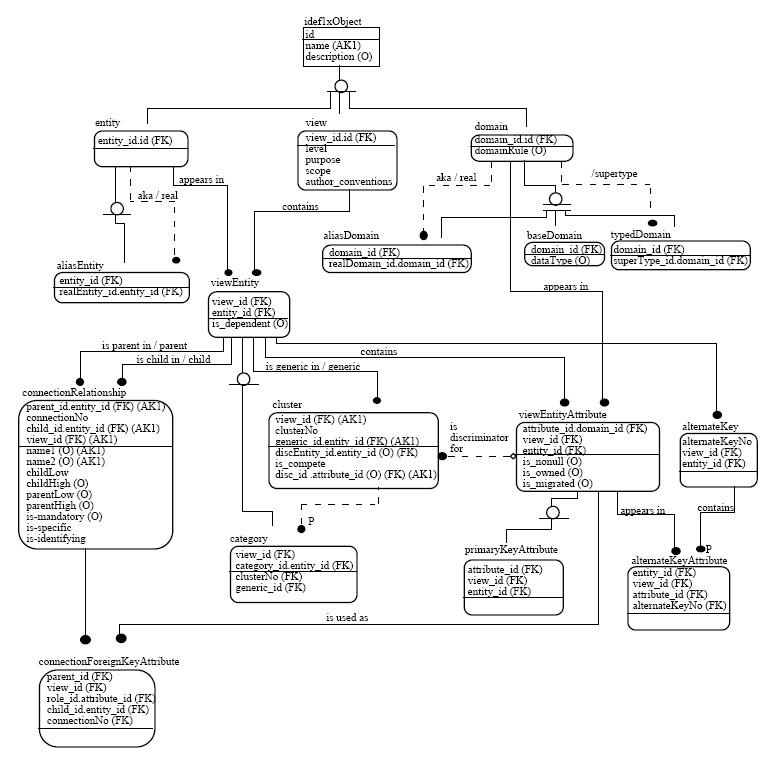

The ICAM Definition (IDEF) Language was developed from the U.S. Air Force ICAM Program during the 1976 to 1982 timeframe.[4] The objective of the ICAM Program, according to Lee (1999), was to increase manufacturing productivity through the systematic application of computer technology. IDEF includes three different modeling methods: IDEF0, IDEF1, and IDEF2 for producing a functional model, an information model, and a dynamic model respectively. IDEF1X is an extended version of IDEF1. The language is in the public domain. It is a graphical representation and is designed using the ER approach and the relational theory. It is used to represent the “real world” in terms of entities, attributes, and relationships between entities. Normalization is enforced by KEY Structures and KEY Migration. The language identifies property groupings (Aggregation) to form complete entity definitions.[1]

EXPRESS was created as ISO 10303-11 for formally specifying information requirements of product data model. It is part of a suite of standards informally known as the STandard for the Exchange of Product model data (STEP). It was first introduced in the early 1990s.[5][6] The language, according to Lee (1999), is a textual representation. In addition, a graphical subset of EXPRESS called EXPRESS-G is available. EXPRESS is based on programming languages and the O-O paradigm. A number of languages have contributed to EXPRESS. In particular, Ada, Algol, C, C++, Euler, Modula-2, Pascal, PL/1, and SQL. EXPRESS consists of language elements that allow an unambiguous object definition and specification of constraints on the objects defined. It uses SCHEMA declaration to provide partitioning and it supports specification of data properties, constraints, and operations.[1]

Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a modeling language for specifying, visualizing, constructing, and documenting the artifacts, rather than processes, of software systems. It was conceived originally by Grady Booch, James Rumbaugh, and Ivar Jacobson. UML was approved by the Object Management Group (OMG) as a standard in 1997. The language, according to Lee (1999), is non-proprietary and is available to the public. It is a graphical representation. The language is based on the objected-oriented paradigm. UML contains notations and rules and is designed to represent data requirements in terms of O-O diagrams. UML organizes a model in a number of views that present different aspects of a system. The contents of a view are described in diagrams that are graphs with model elements. A diagram contains model elements that represent common O-O concepts such as classes, objects, messages, and relationships among these concepts.[1]

IDEF1X, EXPRESS, and UML all can be used to create a conceptual model and, according to Lee (1999), each has its own characteristics. Although some may lead to a natural usage (e.g., implementation), one is not necessarily better than another. In practice, it may require more than one language to develop all information models when an application is complex. In fact, the modeling practice is often more important than the language chosen.[1]

Information models can also be expressed in formalized natural languages, such as Gellish. Gellish, which has natural language variants Gellish Formal English, Gellish Formal Dutch (Gellish Formeel Nederlands), etc. is an information representation language or modeling language that is defined in the Gellish smart Dictionary-Taxonomy, which has the form of a Taxonomy/Ontology. A Gellish Database is not only suitable to store information models, but also knowledge models, requirements models and dictionaries, taxonomies and ontologies. Information models in Gellish English use Gellish Formal English expressions. For example, a geographic information model might consist of a number of Gellish Formal English expressions, such as:

- the Eiffel tower <is located in> Paris - Paris <is classified as a> city

whereas information requirements and knowledge can be expressed for example as follows:

- tower <shall be located in a> geographical area - city <is a kind of> geographical area

Such Gellish expressions use names of concepts (such as 'city') and relation types (such as ⟨is located in⟩ and ⟨is classified as a⟩) that should be selected from the Gellish Formal English Dictionary-Taxonomy (or of your own domain dictionary). The Gellish English Dictionary-Taxonomy enables the creation of semantically rich information models, because the dictionary contains definitions of more than 40000 concepts, including more than 600 standard relation types. Thus, an information model in Gellish consists of a collection of Gellish expressions that use those phrases and dictionary concepts to express facts or make statements, queries and answers.

Standard sets of information models

[edit]The Distributed Management Task Force (DMTF) provides a standard set of information models for various enterprise domains under the general title of the Common Information Model (CIM). Specific information models are derived from CIM for particular management domains.

The TeleManagement Forum (TMF) has defined an advanced model for the Telecommunication domain (the Shared Information/Data model, or SID) as another. This includes views from the business, service and resource domains within the Telecommunication industry. The TMF has established a set of principles that an OSS integration should adopt, along with a set of models that provide standardized approaches.

The models interact with the information model (the Shared Information/Data Model, or SID), via a process model (the Business Process Framework (eTOM), or eTOM) and a life cycle model.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Y. Tina Lee (1999). "Information modeling from design to implementation" National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- ^ Peter Chen (1976). "The Entity-Relationship Model - Towards a Unified View of Data". In: ACM Transactions on database Systems, Vol. 1, No.1, March, 1976.

- ^ The history of conceptual modeling Archived 2012-02-15 at the Wayback Machine at uni-klu.ac.at.

- ^ D. Appleton Company, Inc. (1985). "Integrated Information Support System: Information Modeling Manual, IDEF1 - Extended (IDEF1X)". ICAM Project Priority 6201, Subcontract #013-078846, USAF Prime Contract #F33615-80-C-5155, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, December, 1985.

- ^ ISO 10303-11:1994(E), Industrial Automation Systems and Integration - Product Data Representation and Exchange - Part 11: The EXPRESS Language Reference Manual.

- ^ D. Schenck and P. Wilson (1994). Information Modeling the EXPRESS Way. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1994.

References

[edit]- ISO/IEC TR9007 Conceptual Schema, 1986

- Andries van Renssen, Gellish, A Generic Extensible Ontological Language, (PhD, Delft University of Technology, 2005)

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

Further reading

[edit]- Richard Veryard (1992). Information modelling : practical guidance. New York : Prentice Hall.

- Repa, Vaclav (2012). Information Modeling of Organizations. Bruckner Publishing. ISBN 978-80-904661-3-5.

- Berner, Stefan (2019). Information modelling, A method for improving understanding and accuracy in your collaboration. vdf Zurich. ISBN 978-3-7281-3943-6.

External links

[edit]- RFC 3198 – Terminology for Policy-Based Management

Information model

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

An information model is a structured representation of concepts, entities, relationships, constraints, rules, and operations designed to specify the semantics of data within a particular domain or application.[1] This representation serves as a blueprint for understanding and communicating the meaning of information, independent of any specific technology or implementation details.[7] Key characteristics of an information model include its abstract nature, which allows for an implementation-independent structure that can be realized using various technologies, and its emphasis on defining what information is required rather than how it is stored, processed, or retrieved.[8] By focusing on semantics, these models enable consistent interpretation of data across systems and stakeholders, facilitating interoperability and shared understanding without delving into technical storage mechanisms.[9] In contrast to data models, which concentrate on the physical implementation—such as database schemas, tables, and storage optimization—information models prioritize the conceptual semantics and underlying business rules that govern the data.[8] This distinction ensures that information models remain at a higher level of abstraction, serving as a foundation for deriving more implementation-specific data models.[7] For example, a healthcare information model might define entities like patients, diagnoses, and treatments, along with their interrelationships and constraints (e.g., a diagnosis must be linked to a patient record), without specifying underlying database structures or query languages.[10]Purpose and Benefits

Information models serve as foundational tools in information systems design, primarily to facilitate clear communication among diverse stakeholders by providing a shared, unambiguous representation of data requirements and structures. This shared understanding bridges gaps between business analysts, developers, and end-users, ensuring that all parties align on the semantics and scope of the system from the outset. Additionally, they ensure data consistency across applications by enforcing standardized definitions and constraints, support interoperability between heterogeneous systems through compatible data exchange formats, and guide the progression from high-level requirements to concrete implementation by mapping conceptual needs to technical specifications.[7] The benefits of employing information models extend to practical efficiencies in system development and operation. By reducing ambiguity during requirements gathering, these models minimize misinterpretations that could lead to costly rework, fostering a more precise articulation of business rules and data flows. They enable reuse of established models and components across multiple projects, accelerating development cycles and promoting consistency in data handling. Furthermore, information models enhance data quality by incorporating enforced semantics—such as defined relationships and validation rules—that prevent inconsistencies and errors in data entry and processing, ultimately lowering long-term maintenance costs through more robust, extensible architectures.[7][11] Quantitative evidence underscores these advantages; for instance, studies on standardized information modeling approaches, such as those in building information modeling (BIM) applications, demonstrate up to 30% reductions in overall development time due to streamlined design and integration processes.[12] In broader information systems contexts, data models have enabled up to 10-fold faster implementation of complex logic components compared to traditional methods without such modeling. In agile methodologies, information models support iterative refinement of business rules by allowing flexible updates to the model without disrupting core data structures, thereby maintaining adaptability while preserving underlying integrity.[11][13]Historical Development

Origins in Data Management

The origins of information models can be traced to pre-digital efforts in organizing knowledge, such as the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) system developed by Melvil Dewey in 1876, which provided an analog framework for semantic categorization by assigning hierarchical numerical codes to subjects, thereby enabling systematic retrieval and representation of informational structures.[14] This approach laid early groundwork for abstracting data meanings independent of physical formats, influencing later computational paradigms. In the 1960s, the limitations of traditional file systems—characterized by sequential storage on tapes or disks, high redundancy, and tight coupling to physical hardware—prompted the emergence of structured data management to abstract logical representations from underlying storage, facilitating data portability and independence.[15] This transition was exemplified by IBM's Information Management System (IMS), released in 1968, which introduced a hierarchical model organizing data into tree-like parent-child relationships to represent complex structures efficiently for applications like NASA's Apollo program.[16] Concurrently, the Conference on Data Systems Languages (CODASYL) Database Task Group published specifications in 1969 for the network model, allowing more flexible many-to-many relationships between record types and building on Charles Bachman's Integrated Data Store (IDS) concepts to enhance navigational data access.[17] A pivotal advancement came in 1970 with Edgar F. Codd's seminal paper, "A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks," which proposed representing data through relations (tables) with tuples and attributes, emphasizing logical data independence to separate user views from physical implementation and incorporating semantic structures via keys and normalization to minimize redundancy.[18] This model shifted focus toward declarative querying over procedural navigation, establishing foundational principles for information models that prioritized conceptual clarity and scalability in database systems.Evolution in Computing Standards

The ANSI/SPARC architecture, developed in the late 1970s and formalized through the 1980s, established a foundational three-level modeling framework for database systems—comprising the external (user view), conceptual (logical structure), and internal (physical storage) schemas—that significantly influenced the standardization of information models by promoting data independence and abstraction. This architecture, outlined in the 1977 report of the ANSI/X3/SPARC Study Group, provided a blueprint for separating conceptual representations of data from implementation details, enabling more robust and portable information modeling practices in computing standards. Its adoption in early database management systems helped transition information models from ad-hoc designs to structured, standardized approaches that supported interoperability across diverse hardware and software environments. In the 1990s, the rise of object-oriented paradigms marked a pivotal shift in information modeling, with the Object Data Management Group (ODMG) releasing its first standard, ODMG-93, which integrated semantic richness into database and software engineering by defining a common object model, query language (ODL), and bindings for languages like C++ and Smalltalk. This standard addressed limitations of relational models by incorporating inheritance, encapsulation, and complex relationships, fostering the development of object-oriented database management systems (OODBMS) that treated information models as integral to application development. ODMG's emphasis on portability and semantics influenced subsequent standards, bridging the gap between data persistence and object-oriented programming paradigms in enterprise computing. The 2000s saw information models evolve further through the proliferation of XML for data exchange and the emergence of web services, which paved the way for semantic web initiatives; notably, the W3C's Resource Description Framework (RDF), recommended in 1999, provided a graph-based model for representing metadata and relationships in a machine-readable format, enhancing interoperability on the web.[19] Building on RDF, the Web Ontology Language (OWL), standardized by W3C in 2004, extended information modeling capabilities with formal semantics for defining classes, properties, and inferences, enabling more expressive and reasoning-capable ontologies.[20] These developments, rooted in XML's structured syntax, transformed information models from isolated database schemas into interconnected, web-scale frameworks that supported automated knowledge discovery and integration across distributed systems. As of 2025, recent advancements have integrated artificial intelligence techniques into information modeling, particularly through tools like Protégé for ontology engineering. Protégé, originally developed at Stanford University, supports plugins that enable AI-assisted development and enrichment of ontologies, such as generating terms and relationships from data sources.[21] This integration aligns with broader standards efforts, including those from W3C, to ensure AI-enhanced models maintain compatibility and verifiability, with applications in domains like biomedicine.Core Components

Entities and Attributes

In information modeling, entities represent the fundamental objects or concepts within a domain that capture essential aspects of the real world or abstract structures. An entity is defined as a "thing" which can be distinctly identified, such as a specific person, company, or event.[22] These entities are typically nouns in the domain language, like "Customer" in a customer relationship management (CRM) system, and they form the primary subjects about which information is stored and managed. Entities are distinguishable through unique identifiers, often called keys, which ensure each instance can be referenced independently.[23] Attributes are the descriptive properties or characteristics that provide detailed information about entities, specifying what data can be associated with each entity instance. Formally, an attribute is a function that maps from an entity set into a value set or a Cartesian product of value sets, such as mapping a person's name to a combination of first and last name values.[22] Attributes include elements like customer ID (an integer data type), name (a string), and address (a composite structure), with specifications for data types (e.g., integer, string, date), cardinality (indicating whether single-valued or multivalued), and optionality (whether the attribute must have a value or can be null).[23] These properties ensure attributes accurately reflect the semantics of the domain while supporting data integrity and query efficiency. Attributes are classified into several types based on their structure and derivation. Simple attributes are atomic and indivisible, such as a customer's ID or age, holding a single, basic value without subcomponents.[23] In contrast, complex (or composite) attributes consist of multiple subparts that can be further subdivided, like an address composed of street, city, state, and ZIP code.[23] Derived attributes are not stored directly but computed from other attributes or entities, such as age derived from birthdate using the current date, which avoids redundancy while providing dynamic values.[23] Multivalued attributes, like a customer's multiple phone numbers, allow an entity to hold a set of values for the same property.[23] A representative example is a library information model featuring a "Book" entity. This entity might include attributes such as ISBN (a simple, single-valued key attribute of string type, mandatory), title (simple, single-valued string, mandatory), author (composite, potentially multivalued to handle co-authors, optional for anonymous works), and publication year (simple, single-valued integer, mandatory). In a basic entity-relationship sketch, the "Book" entity would be depicted as a rectangle labeled "Book," with ovals connected by lines representing attributes like ISBN, title, and author, illustrating how these properties describe individual book instances without detailing inter-entity connections.[23]Relationships and Constraints

In information models, relationships define the interconnections between entities, specifying how instances of one entity set associate with instances of another. These relationships are categorized by cardinality, which indicates the number of entity instances that can participate on each side. A one-to-one relationship occurs when exactly one instance of an entity set is associated with exactly one instance of another entity set, such as a marriage linking two persons where each is paired solely with the other.[24] One-to-many relationships allow one instance of an entity set to relate to multiple instances of another, but not vice versa; for example, a department may employ multiple workers, while each worker belongs to only one department.[24] Many-to-many relationships permit multiple instances on both sides, as seen when customers place orders for multiple products, and each product appears in multiple customer orders.[24] To resolve many-to-many relationships while accommodating additional attributes on the association itself, associative entities are introduced. These entities act as intermediaries, transforming the many-to-many link into two one-to-many relationships and enabling the storage of descriptive data about the connection. For instance, in an e-commerce system, an "order details" associative entity links customers and products, capturing attributes like quantity and price for each specific item in an order.[25] Constraints in information models enforce rules that maintain data quality and consistency across relationships and entities. Referential integrity ensures that a foreign key value in one entity references a valid primary key value in a related entity, preventing orphaned records; for example, an order's customer ID must match an existing customer.[26] Uniqueness constraints, part of entity integrity, require that primary keys uniquely identify each entity instance and prohibit null values in those keys, guaranteeing no duplicates or incomplete identifiers.[26] Business rules impose domain-specific conditions, such as requiring an employee's age to exceed 18 for eligibility in certain roles, which are checked to align data with organizational policies.[26] Semantic constraints extend these by incorporating domain knowledge and contextual rules, often addressing complex scenarios like temporality. Temporal constraints, for example, use valid-from and valid-to dates to define the lifespan of entity relationships or attributes, ensuring that historical versions of data remain accurate without overwriting current states; this is crucial in models tracking changes over time, such as employee assignments to projects.[27] These constraints collectively safeguard the model's semantic fidelity, preventing invalid states that could arise from ad-hoc updates.[27]Modeling Languages and Techniques

Conceptual Modeling Approaches

Conceptual modeling approaches encompass high-level, informal techniques employed in the initial phases of information model development to capture and structure domain knowledge without delving into formal syntax or implementation details. These methods prioritize collaboration and creativity to elicit key concepts, ensuring the model reflects real-world semantics accurately. Common approaches include brainstorming sessions, use case analysis, and domain storytelling, each facilitating the identification of entities, relationships, and processes in an accessible manner.[28] Brainstorming sessions involve group activities where participants generate ideas spontaneously to explore domain requirements, often using divergent thinking to map out potential entities and interactions. This technique supports system-level decision-making by identifying tensions and key drivers early, as demonstrated in industrial case studies from the energy sector where engineers used brainstorming to enhance awareness and communication in conceptual models.[28] Use case analysis focuses on describing business scenarios to pinpoint critical entities and their roles, starting from operational narratives to define the foundational elements of an information model. By analyzing how actors interact with the system to achieve goals, this method ensures the model aligns with business needs, forming a bridge to more detailed representations.[29] Domain storytelling, a collaborative workshop-based technique, uses visual narratives with actors, work objects, and activities to depict concrete scenarios, thereby clarifying domain concepts and bridging gaps between experts and modelers. This approach excels in transforming tacit knowledge into explicit models, as seen in software design contexts where it supports agile requirement elicitation.[30] Key techniques within these approaches include top-down and bottom-up strategies for structuring the domain. The top-down method begins with broad, high-level domain overviews, progressively refining into specific concepts, which is effective for strategic alignment in enterprise modeling. In contrast, the bottom-up technique starts from concrete data instances or tasks, aggregating them into generalized entities, allowing for situated knowledge capture from operational levels.[31] Tools such as mind mapping aid conceptualization by visually organizing ideas hierarchically around central themes, facilitating the connection of related concepts and simplifying domain exploration. This radial structure helps in brainstorming and initial entity identification, making complex information more digestible.[32] For incorporating dynamic aspects, process modeling with BPMN can be integrated informally to outline event-driven behaviors alongside static entities, using flow diagrams to represent state changes and interactions without full formalization. This enhances the model's ability to capture temporal and causal relationships in information flows.[33] Best practices emphasize iterative validation with stakeholders to ensure semantic accuracy, involving repeated workshops and feedback loops to refine concepts based on domain expertise. Such cycles, as applied in stakeholder-driven modeling for management systems, build consensus and transparency, reducing misalignment risks before transitioning to formal languages.[34]Formal Languages and Notations

Formal languages and notations enable the precise and unambiguous specification of information models by providing standardized syntax for describing structures, semantics, and constraints. These tools bridge conceptual designs with implementable representations, facilitating communication among stakeholders and automation in software tools. Key examples include diagrammatic and textual approaches tailored to relational, object-oriented, and domain-specific needs. The Entity-Relationship (ER) model, proposed by Peter Chen in 1976, serves as a foundational notation for expressing relational semantics in information models.[22] It represents entities as rectangles, attributes as ovals connected to entities, and relationships as diamonds linking entities, with cardinality constraints indicated by symbols on relationship lines. This visual notation emphasizes data-centric views, making it particularly effective for database schema design where simplicity in relational structures is prioritized. Unified Modeling Language (UML) class diagrams provide a versatile notation for object-oriented information models, as defined in the OMG UML specification. Classes are depicted as boxes with compartments for attributes, operations, and methods; associations are lines connecting classes, often with multiplicity indicators; and generalizations enable inheritance hierarchies. UML class diagrams extend beyond basic relations to include behavioral elements, supporting comprehensive software system modeling. Other notable notations include EXPRESS, a formal textual language standardized in ISO 10303-11 for defining product data models in manufacturing and engineering contexts.[35] EXPRESS supports declarative schemas with entities, types, rules, and functions, allowing machine-interpretable representations without graphical elements. Object-Role Modeling (ORM), developed by Terry Halpin, employs a fact-based approach using textual verbalizations and optional diagrams to model information as elementary facts, emphasizing readability and constraint declaration through roles and predicates.[36] These notations commonly incorporate features such as inheritance for subtype hierarchies, aggregation for part-whole relations without ownership, and composition for stronger ownership semantics, as prominently supported in UML class diagrams. Visual representations, like those in ER and UML, aid human interpretation through diagrams, while textual formats like EXPRESS enable precise, computable specifications suitable for exchange standards.| Notation | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| ER Model | Simpler syntax focused on relational data; easier for database designers to learn and apply in data-centric tasks. | Limited support for behavioral aspects and complex object hierarchies; less adaptable to software engineering beyond databases. |

| UML Class Diagrams | Broader applicability to object-oriented systems; integrates structural and behavioral modeling with rich semantics like inheritance and operations. | Steeper learning curve due to extensive features; potential for over-complexity in pure data modeling scenarios. |