Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

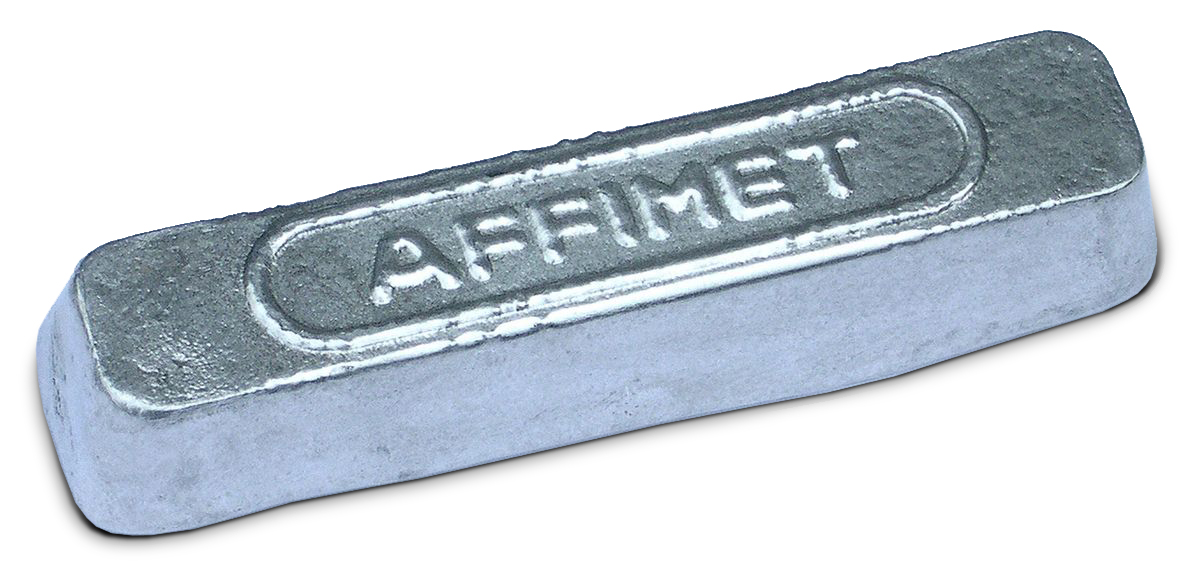

Ingot

View on Wikipedia

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing.[1] In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of shaping, such as cold/hot working, cutting, or milling to produce a useful final product. Non-metallic and semiconductor materials prepared in bulk form may also be referred to as ingots, particularly when cast by mold based methods.[2] Precious metal ingots can be used as currency (with or without being processed into other shapes), or as a currency reserve, as with gold bars.

Types

[edit]Ingots are generally made of metal, either pure or alloy, heated past its melting point and cast into a bar or block using a mold chill method.

A special case are polycrystalline or single crystal ingots made by pulling from a molten melt.

Single crystal

[edit]Single crystal ingots (called boules) of materials are grown (crystal growth) using methods such as the Czochralski process or Bridgman technique.

The boules may be either semiconductor (e.g. electronic chip wafers, photovoltaic cells) or non-conducting inorganic compounds for industrial and jewelry use (e.g., synthetic ruby, sapphire).

Single crystal ingots of metal are produced in similar fashion to that used to produce high purity semiconductor ingots,[3] i.e. by vacuum induction refining. Single crystal ingots of engineering metals are of interest due to their very high strength due to lack of grain boundaries. The method of production is via single crystal dendrite and not via simple casting. Possible uses include turbine blades.

Copper alloys

[edit]In the United States, the brass and bronze ingot making industry started in the early 19th century. The US brass industry grew to be the number one producer by the 1850s.[4] During colonial times the brass and bronze industries were almost non-existent because the British demanded all copper ore be sent to Britain for processing.[5] Copper based alloy ingots weighed approximately 20 pounds (9.1 kg).[6][7]

Manufacture

[edit]

Ingots are manufactured by the cooling of a molten liquid (known as the melt) in a mold. The manufacture of ingots has several aims.

Firstly, the mold is designed to completely solidify and form an appropriate grain structure required for later processing, as the structure formed by the cooling of the melt controls the physical properties of the material.

Secondly, the shape and size of the mold is designed to allow for ease of ingot handling and downstream processing. Finally, the mold is designed to minimize melt wastage and aid ejection of the ingot, as losing either melt or ingot increases manufacturing costs of finished products.

A variety of designs exist for the mold, which may be selected to suit the physical properties of the liquid melt and the solidification process. Molds may exist in the top, horizontal or bottom-up pouring and may be fluted or flat walled. The fluted design increases heat transfer owing to a larger contact area. Molds may be either solid "massive" design, sand cast (e.g. for pig iron), or water-cooled shells, depending upon heat transfer requirements. Ingot molds are tapered to prevent the formation of cracks due to uneven cooling. A crack or void formation occurs as the liquid to solid transition has an associated volume change for a constant mass of material. The formation of these ingot defects may render the cast ingot useless and may need to be re-melted, recycled, or discarded.

The physical structure of a crystalline material is largely determined by the method of cooling and precipitation of the molten metal. During the pouring process, metal in contact with the ingot walls rapidly cools and forms either a columnar structure or possibly a "chill zone" of equiaxed dendrites, depending upon the liquid being cooled and the cooling rate of the mold.[8]

For a top-poured ingot, as the liquid cools within the mold, differential volume effects cause the top of the liquid to recede leaving a curved surface at the mold top which may eventually be required to be machined from the ingot. The mold cooling effect creates an advancing solidification front, which has several associated zones, closer to the wall there is a solid zone that draws heat from the solidifying melt, for alloys there may exist a "mushy" zone, which is the result of solid-liquid equilibrium regions in the alloy's phase diagram, and a liquid region. The rate of front advancement controls the time that dendrites or nuclei have to form in the solidification region. The width of the mushy zone in an alloy may be controlled by tuning the heat transfer properties of the mold or adjusting the liquid melt alloy compositions.

Continuous casting methods for ingot processing also exist, whereby a stationary front of solidification is formed by the continual take-off of cooled solid material, and the addition of a molten liquid to the casting process.[9]

Approximately 70 percent of aluminium ingots in the U.S. are cast using the direct chill casting process, which reduces cracking. A total of 5 percent of ingots must be scrapped because of stress induced cracks and butt deformation.[10]

Historical ingots

[edit]-

Ancient copper oxhide ingot from Zakros, Crete. The ingot is shaped in the form of an animal skin, a typical shape of copper ingots from these times.

-

Lead ingots from Roman Britain on display at the Wells and Mendip Museum.

Plano-convex ingots are widely distributed archaeological artifacts which are studied to provide information on the history of metallurgy.

See also

[edit]- Bar stock (billet)

- Bullion

- Gold bar

- Oxhide ingot

- Sycee, traditional Chinese ingots

- Tin ingot

- Wafer etching

References

[edit]- ^ Chalmers, p. 254.

- ^ Wu, B.; Scott, S.; Stoddard, N.; Clark, R.; Sholapurwalla, A. "Simulation of Silicon Casting Process for Photovoltaic (PV) Application" (PDF).

- ^ Indium ingots Archived 2009-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, lesscommonmetals.com.

- ^ Innovations: The History of Brass Making in the Naugatuck Valley Archived 2009-06-05 at the Wayback Machine. Copper.org (2010-08-25). Retrieved on 2012-02-24.

- ^ Innovations: Overview of Recycled Copper Archived 2017-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. Copper.org (2010-08-25). Retrieved on 2012-02-24.

- ^ Platers' guide: with which is combined Brass world. Brass world publishing co., inc. 1905. pp. 82–. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Arthur Amos Noyes; Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1900). Review of American chemical research. pp. 44–. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Howard F; Flemings, Merton. C; Wulff, John (1959). Foundry Engineering. John Wiley and Sons, New York; Chapman and Hall, London. LCCN 59011811.

- ^ Müller, H. R. (Ed.) (2006). Continuous casting. John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ "Direct Chill Casting Model" (PDF). December 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

Further reading

[edit]- Chalmers, Bruce (1977). Principles of Solidification. Huntington, New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-88275-446-7.

- Schlenker, B.R. (1974). Introduction to Materials. Jacaranda Press.

External links

[edit] Media related to Ingots at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ingots at Wikimedia Commons