Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

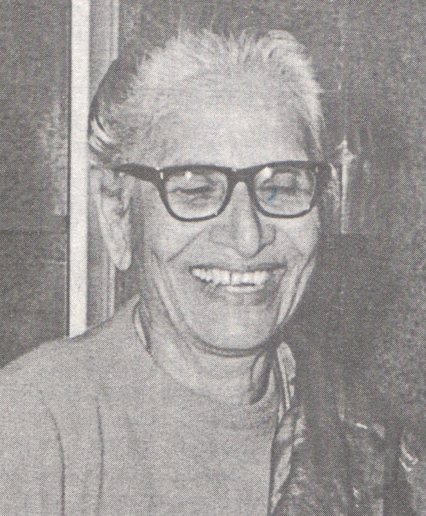

Irawati Karve

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

|

Irawati Karve (15 December 1905[1] – 11 August 1970) was an Indian sociologist, anthropologist, educationist and writer from Maharashtra, India. She was one of the students of G.S. Ghurye, the founder of sociology in India. She has been regarded as the first female Indian sociologist.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Irawati Karve was born on 15 December 1905 to a wealthy Chitpavan Brahmin[3] family and was named after the Irrawaddy River in Burma where her father, Ganesh Hari Karmarkar, was working for the Burma Cotton Company. She attended the girls boarding school Huzurpaga in Pune from the age of seven and then studied philosophy at Fergusson College, from which she graduated in 1926. She then obtained a Dakshina Fellowship to study sociology under G. S. Ghurye at Bombay University, obtaining a master's degree in 1928 with a thesis on the subject of her own caste titled The Chitpavan Brahmans — An Ethnic Study.[4]

Karve married Dinkar Dhondo Karve, who taught chemistry in a school, while studying with Ghurye. [a]Although her husband was from a socially distinguished Brahmin family, the match did not meet with approval from her father, who had hoped that she would marry into the ruling family of a princely state. Dinkar was a son of Dhondo Keshav Karve, a Bharat Ratna and a pioneer of women's education. Somewhat contradictorily, Dhondo Karve, opposed Dinkar's decision to send her to Germany for further studies.[6][7]

The time in Germany, which commenced in November 1928, was financed by a loan from Jivraj Mehta, a member of the Indian National Congress, and was inspired by Dinkar's own educational experiences in that country, where he had obtained his PhD in organic chemistry a decade or so earlier. She studied at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, was awarded a doctorate two years later[b] and then returned to her husband in India, where the couple lived a rather unconventional life less bound by the social strictures that were common at that time.[9][c] Her husband was an atheist and she explained her own visits to the Hindu shrine to Vithoba at Pandharpur as out of deference for "tradition" rather than belief. Despite all this, theirs was essentially a middle-class Hindu family in outlook and deed.[10]

Career

[edit]

Karve worked as an administrator at SNDT Women's University in Bombay from 1931 to 1936 and did some postgraduate teaching in the city. She moved to Pune's Deccan College as a Reader in sociology in 1939 and remained there for the rest of her career.[11]

According to Nandini Sundar, Karve was the first Indian female anthropologist, a discipline that in India during her lifetime was generally synonymous with sociology. She had wide-ranging academic interests, including anthropology, anthropometry, serology, Indology and palaeontology as well as collecting folk songs and translating feminist poetry.[12] She was essentially a diffusionist, inspired by several intellectual schools of thought and in some respects emulating the techniques used by W. H. R. Rivers. These influences included classical Indology, ethnology as practised by bureaucrats of the British Raj and also German eugenics-based physical anthropology. In addition, she had an innate interest in fieldwork.[13] Sundar notes that "as late as 1968 she retained a belief in the importance of mapping social groups like subcastes on the basis of anthropometric and what was then called 'genetic' data (blood group, colour vision, hand-clasping, and hypertrichosis)".[8]

She founded the department of anthropology at what was then Poona University (now the University of Pune).[12]

Karve served for many years as the head of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Deccan College, Pune (University of Pune).[14] She presided over the Anthropology Division of the National Science Congress held in New Delhi in 1947.[12] She wrote in both Marathi and English.

Legacy

[edit]

Sundar says that

although Karve was very well known in her time, especially in her native Maharashtra, and gets an honourable mention in standard histories of sociology/anthropology, she does not seem to have had a lasting effect on the disciplines in the way of some of her contemporaries.

She provides various possible reasons why Karve's effect has been less than that of people such as Ghurye and Louis Dumont. These include her location at an academic centre that carried less prestige than, say, those in Delhi and Bombay and because she concentrated on the classical anthropological concern relating to origins at a time when her fellow academics were moving from that to more specialised matters underpinned by functionalism. In addition, her lasting impact may have been affected due to none of her Ph.D. students being able to carry her work forward: unlike, say, Ghurye's students, they failed to establish themselves in academia. There was also the issue of her use of a niche publisher — her employers, Deccan College — for her early works rather than a mainstream academic house such as Oxford University Press, although this may have been imposed upon her.[12]

After Karve's death, Durga Bhagwat, a contemporary Marathi intellectual who had also studied under Ghurye but left the course, wrote a scathing critique of Karve. Sundar summarises this as containing "charges of plagiarism, careerism, manipulation of persons, suppressing the work of others, etc. Whatever the truth of these charges, the essay does Bhagwat little credit."[15]

Although Karve's work on kinship was based on anthropometric and linguistic surveys that are now considered unacceptable, there has been a revival of academic interest in that and some other aspects of her work, such as ecology and Maharashtrian culture.[12]

Her range of reading was wide, encompassing Sanskrit epics such as the Ramayana to the Bhakti poets, Oliver Goldsmith, Jane Austen, Albert Camus and Alistair MacLean, and her library of books related to academic subjects now forms a part of the collection of Deccan College.[16]

Works

[edit]Among Karve's publications are:

- Kinship Organization in India (Deccan College, 1953), a study of various social institutions in India.

- Hindu Society — an interpretation (Deccan College, 1961), a study of Hindu society based on data which Karve had collected in her field trips, and her study of pertinent texts in Hindi, Marathi, Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrit. In the book, she discussed the caste system and traced its development to its present form.

- Maharashtra — Land and People (1968) – describes various social institutions and rituals in Maharashtra.

- Yuganta: The End of an Epoch, a study of the main characters of the Mahabharata treats them as historical figures and uses their attitudes and behavior to gain an understanding of the times in which they lived. Karve wrote the book first in Marathi, and later translated it into English. The book won the 1967 Sahitya Academy Award for best book in Marathi.[16]

- Paripurti (in Marathi)

- Bhovara (in Marathi) भोवरा

- Amachi Samskruti (in Marathi)

- Samskruti (in Marathi)

- Gangajal (in Marathi)

- The New Brahmans: Five Maharashtrian Families -biography of her father-in-law in a chapter called Grandfather[7]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dinkar Karve later became principal of Fergusson College.[5]

- ^ Karve studied philosophy, Sanskrit and zoology as well as eugenics for her PhD, which was titled The normal asymmetry of the human skull.[8]

- ^ Examples of the Karve family's unconventionality include Irawati's decision not to wear any of the traditional symbols associated with married Hindu women, an unusual degree of familiarity in address between her, her husband and their children, and her being the first woman in Pune to ride a scooter.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Irawati Karmarkar Karve (2007). Anthropology for archaeology: proceedings of the Professor Irawati Karve Birth Centenary Seminar. Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute. p. 19.

Born on 15th December 1905 at Mingyan in Myanmar (then Burma), and named after the River Irawaddy. Her father Hari Ganesh Karmakar worked there in a cotton mill. Her mother's name was Bhagirathi.

- ^ Mollan, Cherylann (19 January 2025). "Irawati Karve: India's trailblazing female anthropologist who challenged Nazi race theories". BBC. Retrieved 19 January 2025.

- ^ Patricia Uberoi; Nandini Sundar; Satish Deshpande (2008). Anthropology in the East: founders of Indian sociology and anthropology. Seagull. p. 367. ISBN 978-1-905422-78-4.

In this general atmosphere of reform and women's education, and coming from a professional Chitpavan family, neither getting a education nor going into a profession like teaching would for someone like Irawati Karve have been particularly novel.

- ^ Sundar (2007), pp. 367–368, 377

- ^ Sundar (2007), p. 370

- ^ Sundar (2007), pp. 368–369

- ^ a b Dinakar Dhondo Karve (1963). The New Brahmans: Five Maharashtrian Families. University of California Press. p. 93. GGKEY:GPD3WDWREYG.

- ^ a b Sundar (2007), p. 380

- ^ Sundar (2007), pp. 370–371, 378

- ^ a b Sundar (2007), p. 371

- ^ Sundar (2007), pp. 380–381

- ^ a b c d e Sundar (2007), pp. 360–364

- ^ Sundar (2007), pp. 373–380

- ^ Frank Spencer (1997). History of Physical Anthropology, Volume 2. Taylor & Francis. p. 558. ISBN 9780815304906.

- ^ Sundar (2007), p. 374

- ^ a b Sundar (2007), p. 372

Bibliography

[edit]- Sundar, Nandini (2007), "In the cause of anthropology: the life and work of Irawati Karve", in Uberoi, Patricia; Sundar, Nandini; Deshpande, Satish (eds.), Anthropology in the East: The founders of Indian Sociology and Anthropology, New Delhi: Permanent Black, ISBN 978-1-90542-277-7

Irawati Karve

View on GrokipediaIrawati Karve (15 December 1905 – 11 August 1970) was an Indian anthropologist and academic who pioneered the integration of Indological texts with ethnographic fieldwork to study kinship, caste, and ancient societal structures.[1][2] Born in Myingyan, Burma, to a Chitpavan Brahmin engineer father, she pursued doctoral studies in anthropology at the University of Berlin starting in 1927, earning her degree under Eugen Fischer at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute.[3][1] There, she conducted craniometric research on 149 skulls to refute hypotheses of Aryan racial superiority based on nasal index and skull asymmetry, challenging scientific premises later exploited by Nazi ideology.[3][2] Returning to India, Karve became the first woman appointed to a university professorship in anthropology, establishing and leading the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Deccan College, Pune, for nearly 40 years.[1][4] Her seminal publications, including Kinship Organization in India (1953) and Yuganta: The End of an Epoch (1967), employed secular, anthropological lenses to dissect Hindu social systems and reframe Mahabharata protagonists as products of historical kinship dynamics rather than mythic ideals.[2][1]