Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jain schools and branches

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

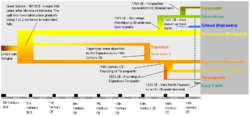

Jainism is an Indian religion which is traditionally believed to be propagated by twenty-four spiritual teachers known as tirthankara. Broadly, Jainism is divided into two major schools of thought, Digambara and Śvetāmbara. These are further divided into different sub-sects and traditions. While there are differences in practices, the core philosophy and main principles of each sect is the same.

Schism

[edit]Traditionally, the original doctrine of Jainism was contained in scriptures called Purva. There were fourteen Purva. These are believed to have originated from Rishabhanatha, the first tirthankara.[1] There was a twelve-year famine around fourth century BCE.[2] According to Śvētāmbara texts - The undivided Jain sangha was headed by Acharya Krishnasuri, who initiated Sivabhuti as a monk.[3][4][5][6] As a result of his rebellion, anger, and gross misinterpretation of the canonical scriptures of Jainism, he began roaming naked and propagating that public nudity was accepted as per Jain scriptures.[7] Followers of Sivabhuti came to be known as Digambaras. This is how the Digambara and Śvetāmbara sects present differing accounts of the division.[8][9][10][11] The Digambara being the naked ones where as Śvetāmbara being the white clothed. According to Digambara, the purvas and the angas were lost.[12] About 980 to 993 years after the Nirvana of Mahavira, a Vallabhi council was held at Vallabhi (now in Gujarat). This was headed by Devardhi Ksamashramana.[12][13] It was found that the 12th Anga, the Ditthivaya, was lost too. The other Angas were written down.[12] This is a traditional account of schism.[14] According to Śvetāmbara, there were eight schisms (Nihnava).[15]

According to Digambara tradition, Ganadhara knew fourteen Purva and eleven Anga. Knowledge of Purva was lost around 436 years after Mahavira and Anga were lost around 683 years after Mahavira.[16] The texts which do not belong to Anga are called Angabahyas. There were fourteen Angabahyas. The first four Angabahyas, Samayika, Chaturvimasvika, Vandana and Pratikramana corresponds to sections of second Mulasutra of Śvetāmbara. The only texts of angabahyas which occurs in Śvetāmbara texts are Dasavaikalika, Uttaradhyayana and Kalpavyavahara.[17]

Early Jain images from Mathura depict iconography of the Śvetāmbara sect. Differences between Digambara and Śvetāmbara sects deepened when Bappabhattisuri defeated Digambaras at Girnar Jain temples.[18]

Differences

[edit]Other than rejecting or accepting different ancient Jain texts, Digambaras and Śvetāmbara differ in other significant ways such as:

- Śvetāmbaras trace their practices and dress code to the teachings of Parshvanatha, the 23rd tirthankara, which they believe taught only Four restraints (a claim, scholars say are confirmed by the ancient Buddhist texts that discuss Jain monastic life). However, Śvetāmbara monks also follow Five restraints as Mahāvīra taught. Mahāvīra taught Five vows, which both the sects follow.[19][20][21] The Digambara sect disagrees with the Śvetāmbara interpretations,[22] and reject the theory of difference in Parshvanatha and Mahāvīra's teachings.[20]

- Digambaras believe that both Parshvanatha and Mahāvīra remained unmarried, whereas Śvetāmbara believe the 23rd and 24th did indeed marry. According to the Śvetāmbara version, Parshva married Prabhavati,[23] and Mahāvīra married Yashoda who bore him a daughter named Priyadarshana.[24][25] The two sects also differ on the origin of Trishala, Mahāvīra's mother,[24] as well as the details of Tirthankara's biographies such as how many auspicious dreams their mothers had when they were in the wombs.[26]

- Digambara believe Rishabha, Vasupujya and Neminatha were the three tirthankaras who reached omniscience while in sitting posture and other tirthankaras were in standing ascetic posture. In contrast, Śvetāmbaras believe it was Rishabha, Nemi and Mahāvīra who were the three in sitting posture.[27]

- Digambara iconography are plain, Śvetāmbara icons are decorated and colored to be more lifelike.[28]

- According to Śvetāmbara Jain texts, from Kalpasūtras onwards, its monastic community has had more sadhvis than sadhus (female than male mendicants). In Tapa Gacch of the modern era, the ratio of sadhvis to sadhus (nuns to monks) is about 3.5 to 1.[29] In contrast to Śvetāmbara, the Digambara sect monastic community has been predominantly male.[30]

- In the Digambara tradition, a male human being is considered closest to the apex with the potential to achieve his soul's liberation from rebirths through asceticism. Women must gain karmic merit, to be reborn as man, and only then can they achieve spiritual liberation in the Digambara sect of Jainism.[31][32] The Śvetāmbaras disagree with the Digambaras, believing that women can also achieve liberation from Saṃsāra through ascetic practices.[32][33]

- The Śvetāmbaras state the 19th Tirthankara Māllīnātha was female.[34] Digambaras reject this, and believe Mallinatha was male. However, several Digambara idols such as the one at Keshorai Pattan depict Mallinatha as female.[35]

Digambara

[edit]

Digambara (sky-clad) is one of the two main sects of Jainism.[36] This sect of Jainism rejects the authority of the Jain Agama compiled at the Vallabhi Council under the leadership of Devardhigani Kshamashraman.[37] They believe that by the time of Dharasena, the twenty-third teacher after Gandhar Gautama, knowledge of only one Anga was there. This was about 683 years after the death of Mahavira. After Dharasena's pupils Acharya Puspadanta and Bhutabali. They wrote down the Shatkhandagama, the only scripture of the digambara sect. The other scripture is the Kasay-pahuda.[38][39] According to Digambara tradition, Mahavira, the last jaina tirthankara, never married. He renounced the world at the age of thirty after taking permission of his parents.[40] The Digambara believe that after attaining enlightenment, Mahavira was free from human activities like hunger, thirst, and sleep.[41] Digambara monks tradition do not wear any clothes. They carry only a broom made up of fallen peacock feathers and a water gourd.[42] One of the most important scholar-monks of Digambara tradition was Acharya Kundakunda. He authored Prakrit texts such as Samayasara and Pravachansara. Samantabhadra was another important monk of this tradition.[43]

Digambar tradition has two main monastic orders Mula Sangh and the Kashtha Sangh, both led by Bhattarakas. Other notable monastic orders include the Digambara Terapanth which emerged in the 17th century.[44] Śvetāmbaras have their own sanghs, but unlike Digambaras which have had predominantly sadhu sanghs (male monastic organizations), they have major sadhu and sadhvi sanghs (monks and nuns).[45]

Monastic orders

[edit]Mula Sangh is an ancient monastic order. Mula literally means root or original.[46] The great Acharya Kundakunda is associated with Mula Sangh. The oldest known mention of Mula Sangh is from 430 CE. Mula Sangh was divided into a few branches. According to Shrutavatara and Nitisar of Bhattaraka Indranandi, Acharya Arhadbali had organised a council of Jain monks, and had given names (gana or sangha) to different groups.[citation needed]

Kashtha Sangha was a monastic order once dominant in several regions of North and Western India. It is said to have originated from a town named Kashtha. The origin of Kashtha Sangha is often attributed to Lohacharya in several texts and inscriptions from Delhi region.[47] The Kashtasangh Gurvavali identifies Lohacharya as the last person who knew Acharanga in the Digambara tradition, who lived until around 683-year after the nirvana of Lord Mahavira.[48] Several Digambara orders in North India belonged to Kashtha Sangha. The Agrawal Jains were the major supporters of Kashtha Sangha. They were initiated by Lohacharya. Kashta Sangha has several orders including Nanditat gachchha,[49]

The Digambar Terapanth subsect was formed by Amra Bhaunsa Godika and his son Jodhraj Godika during 1664–1667 in opposition to the bhattakaras. The Bhattaraka are the priestly class of Jainism who are responsible for maintaining libraries and other Jain institutions.[50] The Terapanth sub-sect among the Digambara Jains emerged around the Jaipur (Sanganer, Amber and Jaipur region itself).[44] Godika duo expressed opposition to the Bhattaraka Narendrakirti of Amber. Authors Daulatram Kasliwal and Pandit Todarmal[51]) were associated with the Terapanth movement. They opposed worship of various minor gods and goddesses. Some Terapanthi practices, like not using flowers in worship, gradually spread throughout North India among the Digambaras.[52] Bakhtaram in his "Mithyatva Khandan Natak" (1764) mentions that group that started it included thirteen individuals, who collectively built a new temple, thus giving it its name Tera-Panth (Thirteen Path). However, according to "Kavitta Terapanth kau" by a Chanda Kavi, the movement was named Tera Panth, because the founders disagreed with the Bhattaraka on thirteen points. A letter of 1692 from Tera Panthis at Kama to those at Sanganer mentions thirteen rituals that were rejected. These are mentioned in Buddhivilas (1770) of Bakhtaram. These are– authority of Bhattarakas, Use of flowers, cooked food or lamps, Abhisheka (panchamrita), consecration of images without supervision by the representatives of Bhattarakas, Puja while seated, Puja at night, Using drums in the temple and Worship of minor gods like dikpalas, shasan devis (Padmavati etc.) and Kshetrapal. The Digambara Jains who have continued to follow these practices are termed Bispanthi. This sub-sect opposes use of flowers for worship of Tirthankara idols. However, use of flowers to worship monks and nuns is widespread amongst followers of Digambar Terapanth.[citation needed]

The Taran Panth was founded by Taran Svami in Bundelkhand in 1505.[53] They do not believe in idol worshiping. Instead, the taranapantha community prays to the scriptures written by Taran Swami.[citation needed] Taran Svami is also referred to as Taran Taran, the one who can help the swimmers to the other side, i.e. towards nirvana. A mystical account of his life, perhaps an autobiography, is given in Chadmastha Vani. The language in his fourteen books is a unique blend of Prakrit, Sanskrit and Apabhramsha. His language was perhaps influenced by his reading of the books of Acharya Kundakunda. Commentaries on six of the main texts composed by Taran Svami were written by Brahmacari Shitala Prasad in the 1930s. Commentaries on other texts have also been written recently. Osho, who was born into a Taranpanthi family, has included Shunya Svabhava and Siddhi Svabhava as among the books that influenced him most.[54] The number of Taranpanthis is very small. Their shrines are called Chaityalaya (or sometimes Nisai/Nasia). At the altar (vimana) they have a book instead of an idol. The Taranpanthis were originally from six communities.

Criticism of monasticism and beliefs

[edit]Several scholars and scriptures of other religions as well as those of their counterpart Śvetāmbara Jains[55] criticize their practices of public nudity as well as their belief that women are incapable of attaining spiritual liberation.[56][57][58]

Śvetāmbara

[edit]

The Śvetāmbara (white-clad) is one of the two main sects of Jainism. Śvetāmbara is a term describing its ascetics' practice of wearing white clothes, which sets it apart from the Digambara whose ascetic practitioners go naked.[61] Śvetāmbaras, unlike Digambaras, do not believe that ascetics must practice nudity. Śvetāmbara monks usually wear white maintaining that nudism is no longer practical. Śvetāmbaras also believe that women are able to obtain moksha. Śvetāmbaras maintain that the 19th Tirthankara, Mallinath, was a woman. Some Śvetāmbara monks and nuns (Sthanakvasis and Terapanthis) cover their mouth with a white cloth or muhapatti to practise ahimsa even when they talk.[62] By doing so they minimise the possibility of inhaling small organisms. The Śvetāmbara tradition follows the lineage of Acharya Sthulibhadra Suri. The Kalpa Sūtra mentions some of the lineages in ancient times.[63]

Both of the major Jain traditions evolved into sub-traditions over time. For example, the devotional worship traditions of Śvetāmbara are referred to as Murti-pujakas, those who live in and around Jain temples became Deravasi or Mandira-margi. Those who avoid temples and pursue their spirituality at a designated monastic meeting place came to be known as Sthānakavāsī.[64][65]

Śvētāmbaras who are not Sthānakavāsins are called Murtipujaka (Idol-worshipers). Murtipujaka differ from Sthanakvasi Śvetāmbara in that their derasars contain idols of the Tirthankaras instead of empty rooms. They worship idols and have rituals for it. Murtipujaka monastics and worshippers do not use the muhapatti, a piece of cloth over the mouth, during prayers, whereas it is permanently worn by Sthanakvasi. The most prominent among the classical orders called Gacchas today are the Kharatara, Tapa and the Tristutik. Major reforms by Vijayanandsuri of the Tapa Gaccha in 1880 led a movement to restore orders of wandering monks, which brought about the near-extinction of the Yati institutions. Acharya Rajendrasuri restored the shramana organisation in the Tristutik Order.[66]

- Murtipujaka Śvetāmbara monastic orders

The monks of Murtipujaka sect are divided into 4 orders or Gaccha. These are:[67]

- Kharatara Gaccha (1023 CE)

- Ancala Gaccha(1156 CE)

- Tapa Gaccha (1228 CE)

- Parsvacandra Gaccha (1515 CE)

Kharatara Gaccha is one of Śvetāmbara gacchas.[68][69] It was founded by Vardhamana Suri[69] (1031). His teacher was a temple-dwelling monk. He rejected him because of not following texts.[68] His pupil, Jineshvara, got honorary title 'Kharatara' (Sharp witted or Fierce) because he defeated Suracharya, leader of Chaityavasis in public debate in 1023 at Anahilvada Patan. So the Gaccha got his title.[69] Another tradition regards Jinadatta Suri (1075–1154) as a founder of Gaccha.[69][68]

Tristutik Gaccha was a Murtipujaka Śvetāmbara Jain religious grouping preceding the founding of the Tapa Gaccha by Acharya Rajendrasuri. It was established in 1194. It was known as Agama Gaccha in ancient times. The Tristutik believed in devotion to the Tirthankaras alone in most rituals, although offerings to helper divinities were made during large ceremonies. The Tristutik Gaccha was reformed by Acharya Rajendrasuri.

Tapa Gaccha is the largest monastic order of Śvetāmbara Jainism. It was founded by Acharya Jagat Chandrasuri in 1229. He was given the title of "Tapa" (i.e. the meditative one) by the ruler of Mewar. Vijayananda Suri was responsible for reviving the wandering orders among the Śvetāmbara monks. As a result of this reform, most Śvetāmbara Jain monks today belong to the Tapa Gaccha.

The Sthanakwasi arose not directly from the Shwetambars but as reformers of an older reforming sect, viz., the Lonka sect of Jainism. This Lonka sect was founded in about 1474 A.D. by Lonkashah, a rich and well-read merchant of Ahmedabad. The main principle of this sect was not to practice idol-worship. Later on, some of the members of the Lonka sect disapproved of the ways of life of their current ascetics, declaring that they lived less strictly than Mahavira would have wished. A Lonka sect layman, Viraji of Surat, received initiation as a Yati, i.e., an ascetic, and won great admiration on account of the strictness of his life. Many people of the Lonka sect joined this reformer and they took the name of Sthanakwasi, thereby intending to strictly follow on the principles of Lord Mahavir. Sthanakvasi means those who do not have their religious activities in temples but carry on their religious duties in places known as Sthanakas which are like prayer-halls.

During the time of Acharya Dharmadasji Swami, the tradition underwent a major revival through the efforts of five great monks—Jivraji Swami, Harji Rishi, Dharmsinhji Swami, Lavaji Rishi, and Dharmadasji Swami—who strengthened its foundations even during challenging times. From these spiritual leaders arose several sub-sects that carried their teachings forward. Lavaji Rishi’s disciples established the Khambhat Sampraday, while Dharmsinhji Swami’s followers formed the Dariyapuri Sampraday. Other regions such as Kutch, Kathiawad, and Zalawad maintained lineages tracing back to Dharmadasji Swami. In Rajasthan, the Bavish Tola Sampraday also originated from his tradition.

A major transformation occurred in 1836 when the system of naming sects changed. Until then, each sect was identified by its founding saint, but after a historic Jain assembly in Gujarat, leaders began establishing new communities across different regions. This led to sects being named after their geographical locations, such as Gondal, Limbdi, and Barwala-Batod Sampradays. This regional naming convention became the norm in Gujarat, while in Marwar, sects continued to be named after their Gurus, preserving the older tradition. Since its establishments, the sthanakvasis have seen visionary and revolutionary monks and nuns who have contributed to the uplifment of the Jain religion, including presently such as Rashtrasant Param Gurudevshree Namramuni Maharajsaheb.

Terapanth is another reformist religious sect under Śvetāmbara Jainism. It was founded by Acharya Bhikshu, also known as Swami Bhikanji Maharaj. Swami Bhikanji was formerly a Sthanakvasi saint and had initiation by Acharya Raghunatha. But he had differences with his Guru on several aspects of religious practices of Sthanakvasi ascetics. Hence he left the Sthanakvasi sect with the motto of correcting practise of Jain monks, eventually on 28 June 1760 at Kelwa, a small town in Udaipur district of Rajasthan state, Terapanth was founded by him. This sect is also non-idolatrous.[70][71][72][73]

About the 18th century, the Śvetāmbara and Digambara traditions saw an emergence of separate Terapanthi movements.[65][74][75] Śvetāmbara Terapanth was started by Acharya Bhikshu in 18th century.[76]

Yapaniya

[edit]Yapaniya was a Jain order in western Karnataka which is now extinct. The first inscription that mentions them by Mrigesavarman (AD 475–490) a Kadamba king of Palasika who donated for a Jain temple, and made a grant to the sects of Yapaniyas, Nirgranthas (identifiable as Digambaras), and the Kurchakas (not identified).[77][78] The last inscription which mentioned the Yapaniyas was found in the Tuluva region southwest Karnataka, dated Saka 1316 (1394 CE).[79] Yapaniya rose to its dominance in second century CE and declined after their migration to Deccan merging with Digambara or Śvetāmbara.[80] The Yapaniyas worshipped nude images of the Tirthankaras in their temples and their monks were nudes, but they occasionally allowed clothes in case of disease or bodily needs. Moreover, the yapaniyas believed that women were able to achieve nirvana which the Śvetāmbaras also believe.[81] According to Acharya Shrutsagarsuri, Yapaniyas also believed that followers of other doctrines could achieve nirvana, and Yapaniya monks were allowed to wear blankets and sheets to protect themselves from the cold and wore clothes to protect themselves and others from infections and diseases which makes them closer to Śvetāmbaras than Digambaras who strictly believe that only adherents of the Digambara sect can achieve liberation and that nudity is mandatory to achieve liberation.[82]

Kundakunda-inspired lay-movements

[edit]The 8th-century scholar Kundakunda inspired two contemporary lay-movements within Jainism with his Mahayana Buddhism-inspired[83] notion of two truths and his emphasis on direct insight into niścayanaya or ‘ultimate perspective’, also called “supreme” (paramārtha) and “pure” (śuddha).[a]

Shrimad Rajchandra (1867-1901) was a Jain poet and mystic who was inspired by works of Kundakunda and Digambara mystical tradition. Nominally belonging to the Digambara tradition,[87] his followers sometimes consider his teaching as a new path of Jainism, neither Śvetāmbara nor Digambara, and revere him as a saint. His path is sometimes referred as Raj Bhakta Marg, Kavipanth, or Shrimadiya, which has mostly lay followers as was Rajchandra himself.[88] His teachings influenced Kanji Swami, Dada Bhagwan,[89] Rakesh Jhaveri (Shrimad Rajchandra Mission), Saubhagbhai, Lalluji Maharaj (Laghuraj Swami), Atmanandji and several other religious figures.

Kanji Panth is a lay movement founded by Kanji Swami (1890-1980).[90] Nominally it belongs to the Śvetāmbara[91] but is inspired by Kundakunda and Shrimad Rajchandra (1867-1901), though "lacking a place in any Digambara ascetic lineage descending from Kundakunda."[90] Kanji Swami has many followers in the Jain diaspora.[92] They generally regard themselves simply as Digambara Jains, more popularly known as Mumukshu, following the mystical tradition of Kundakunda and Pandit Todarmal.[90]

Bauer notes that "[in] recent years there has been a convergence of the Kanji Swami Panth and the Shrimad Rajcandra movement, part of trend toward a more eucumenical and less sectarian Jainism among educated, mobile Jains living overseas."[93]

The Akram Vignan Movement established by Dada Bhagwan draws inspiration from teachings of Rajchandra and other Jain scriptures, though it is considered as a Jain-Vaishnava Hindu syncretistic movement.[94]

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Long, this view shows influence from Buddhism and Vedanta, which see bondage are arising from avidya, ignorance, and see the ultimate solution to this in a form of spiritual gnosis.[84] Johnson also notes that "his use of a vyavahara/niscaya distinction [...] has more in common with Madhyamaka Buddhism and even more with Advaita Vedanta than with the Jain philosophy of Anekantavada."[85] Cort, referring to Johnson, notes that "a minority position exemplified by Kundakunda has deemphasized conduct and focused upon knowledge alone."[86]

References

[edit]- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Clarke & Beyer 2009, p. 326.

- ^ Bombay, Anthropological Society of (1928). Journal ... Anthropological Society of Bombay.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 46.

- ^ Sogani, Kamal Chand (1967). Ethical Doctrines in Jainism. Lalchand Hirachand Doshi; [copies can be had from Jaina Saṁskṛti Saṁrakshaka Sangha].

- ^ Paszkiewicz, Joshua R. (7 May 2024). Indian Spirituality: An Exploration of Hindu, Jain, Buddhist, and Sikh Traditions. Wellfleet Press. ISBN 978-1-57715-425-9.

- ^ Nagraj, Muni (1986). Āgama Aura Tripiṭaka, Eka Anuśilana: Language and Literature. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-731-1.

- ^ Rao, B. S. L. Hanumantha (1973). Religion in Āndhra: A Survey of Religious Developments in Āndhra from Early Times Upto A.D. 1325. Welcome Press.

- ^ Murti, D. Bhaskara (2004). Prāsādam: Recent Researches on Archaeology, Art, Architecture, and Culture : Professor B. Rajendra Prasad Festschrift. Harman Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-86622-67-4.

- ^ Bhandarkar, Sir Ramkrishna Gopal (1927). Collected Works of Sir R. G. Bhandarkar: Miscellaneous articles, reviews, addresses &c. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

- ^ Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander (1914). Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics: Confirmation-Drama. T. & T. Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-06509-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b c Winternitz 1993, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 72.

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 383.

- ^ Winternitz 1993, p. 417.

- ^ Winternitz 1993, p. 455.

- ^ Vyas 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2007, p. 211.

- ^ a b Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 5.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Jaini 2000, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 12.

- ^ a b Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Dalal 2010a, p. 167.

- ^ Cort 2001a, p. 47.

- ^ Flügel 2006, pp. 314–331, 353–361.

- ^ Long 2013, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Harvey 2016, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 55–59.

- ^ Vallely 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 23.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 444.

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2007, p. 134.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 313.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 314.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 316.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 524.

- ^ a b John E. Cort (2002). "A Tale of Two Cities: On the Origins of Digambara Sectarianism in North India". In L. A. Babb; V. Joshi; M. W. Meister (eds.). Multiple Histories: Culture and Society in the Study of Rajasthan. Jaipur: Rawat. pp. 39–83.

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 48–59.

- ^ Jain Dharma, Kailash Chandra Siddhanta Shastri, 1985.

- ^ "Muni Sabhachandra Avam Unka Padmapuran" (PDF). Idjo.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "(International Digamber Jain Organization)". IDJO.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "History of the Birth of Shree Narsingpura Community". Narsingpura Digambar Jain Samaj. Ndjains.org. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009.

- ^ Sangave 2001, pp. 133–143

- ^ "The Illuminator of the Path of Liberation By Acharyakalp Pt. Todamalji, Jaipur". Atmadharma.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Taranpanthis". Philtar.ucsm.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Smarika, Sarva Dharma Sammelan, 1974, Taran Taran Samaj, Jabalpur

- ^ "Books I have Loved". Osho.nl. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Gender and Salvation". publishing.cdlib.org. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ The Ādi Granth: Or, Holy Scriptures of the Sikhs. Wm. H. Allen. 1877.

- ^ "Nudity". Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Guide To Buddhism A To Z". www.buddhisma2z.com. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ Quintanilla 2007, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Jaini & Goldman 2018, pp. 42–45.

- ^ "Svetambara".

- ^ "Sthanakvasi".

- ^ "Kalpa Sutra, translated by Herman Jacobi".

- ^ Dalal 2010a, p. 341.

- ^ a b "Sthanakavasi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017.

- ^ Jain, Arun Kumar (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Jainism. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7835-723-2.

- ^ Flügel 2006, p. 317.

- ^ a b c "Overview of world religions-Jainism-Kharatara Gaccha". Philtar.ac.uk. Division of Religion and Philosophy, University of Cumbria. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d Glasenapp 1999, p. 389.

- ^ Dundas, p. 254

- ^ Shashi, p. 945

- ^ Vallely, p. 59

- ^ Singh, p. 5184

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 41, 60.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 155–157, 249–250, 254–259.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 249.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Prasad S, Shyam (11 August 2022). "Karnataka: Inscription may unlock Jain heritage secrets". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Jainism in South India and Some Jaina Epigraphs By Pandurang Bhimarao Desai, 1957, published by Gulabchand Hirachand Doshi, Jaina Saṁskṛti Saṁrakshaka Sangha

- ^ Jaini 1991, p. 45.

- ^ "Yapaniyas". jainworld.jainworld.com. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ "Yapaniya - The lost sect of Jains". 28 September 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ Long 2013, p. 66, 126.

- ^ Long 2013, p. 127.

- ^ Johnson 1995, p. 137.

- ^ Cort 1998, p. 10.

- ^ Prakash C. Jain 2025, p. 7,9.

- ^ Salter 2002.

- ^ Flügel 2005, p. 194–243.

- ^ a b c Shaw.

- ^ "Jainism". Philtar.ac.uk. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Bauer 2004, p. 464.

- ^ Bauer 2004, p. 465.

- ^ Flügel 2005.

Sources

[edit]- Bauer, Jerome (2004). "Kanji Swami (1890-1980)". In Jestice, Phyllis G. (ed.). Holy People of the World: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 464. ISBN 9781576073551.

- Clarke, Peter; Beyer, Peter (2009), The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-87212-3

- Cort, John E. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-3785-X

- Cort, John E. (2001a), Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513234-2

- Dalal, Roshen (2010a) [2006], The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Flügel, Peter (2005). "Present Lord: Simandhara Svami and the Akram Vijnan Movement" (PDF). In King, Anna S.; Brockington, John (eds.). The Intimate Other: Love Divine in the Indic Religions. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 194–243. ISBN 9788125028017.

- Flügel, Peter (2006), Studies in Jaina History and Culture: Disputes and Dialogues, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-23552-0

- Glasenapp, Helmuth von (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- Harvey, Graham (2016), Religions in Focus: New Approaches to Tradition and Contemporary Practices, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-93690-8

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Jain, Prakash C. (2025). Jains in India and Abroad: A Sociological Introduction. DK Printworld.

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1991), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06820-3

- Jaini, Padmanabh S.; Goldman, Robert (2018), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-30296-9

- Jaini, Padmanabh S., ed. (2000), Collected Papers on Jaina Studies (First ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6

- Johnson, W.J. (1995), Harmless Souls: Karmic Bondage and Religious Change in Early Jainism with Special Reference to Umāsvāti and Kundakunda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1309-0

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9

- Long, Jeffery D. (2013), Jainism: An Introduction, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-0-85771-392-6

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007), History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE, Brill, ISBN 978-9-004-15537-4

- Salter, Emma (2002). Raj Bhakta Marg: the path of devotion to Srimad Rajcandra. A Jain community in the twenty first century (Doctoral thesis). University of Wales. pp. 98–108, 247, 251. Retrieved 21 September 2018 – via University of Huddersfield Repository.

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (1980), Jain Community: A Social Survey (2nd ed.), Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-0-317-12346-3

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6

- Shaw, Richard. "Kanji swami Panth". University of Cumbria. Division of Religion and philosophy. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Singh, Ram Bhushan Prasad (2008). Jainism In Early Medieval Karnataka. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3323-4.

- Vallely, Anne (2002), Guardians of the Transcendent: An Ethnology of a Jain Ascetic Community, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-8415-6

- Vyas, Dr. R. T., ed. (1995), Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects, The Director, Oriental Institute, on behalf of the Registrar, M.S. University of Baroda, Vadodara, ISBN 81-7017-316-7

- Winternitz, Maurice (1993) [1983], A History of Indian Literature: Buddhist literature and Jaina literature, vol. II, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0265-9

Jain schools and branches

View on Grokipedia| Aspect | Digambara | Śvetāmbara |

|---|---|---|

| Monastic Attire | Monks: nude; Nuns: white robes | All: white robes |

| Women's Liberation | Impossible without rebirth as male | Possible |

| Canonical Texts | Siddhānta (e.g., Kaṣāyapāhuda) | Āgamas (e.g., 12 Aṅgas) |

| Images of Tīrthaṅkaras | Nude, eyes closed | Clothed, eyes open |

| Mahāvīra's Life | Unmarried, no possessions | Married, had a daughter |