Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Satya

View on Wikipedia

Satya (Sanskrit: सत्य; IAST: Satya) is a Sanskrit word that can be translated as "truth" or "essence.“[3] Across Indian religions, it stands as a deeply valued virtue, signifying the alignment of one's thoughts, speech and actions with reality.[4] In Yoga philosophy, particularly in Patañjali's Yoga Sutras, Satya is one of the five yamas—moral restraints designed to cultivate truthfulness and prevent the distortion of reality through one’s expressions and behavior.[5]

Etymology and meaning

[edit]In the Vedas and later sutras, the meaning of the word satya evolves into an ethical concept about truthfulness and an important virtue.[4][6] It means being true and consistent with reality in one's thought, speech, and action.[4]

Satya has cognates in a number of diverse Indo-European languages, including the word "sooth" and "sin" in English, "istina" ("истина") in Russian, "sand" (truthful) in Danish, "sann" in Swedish, and "haithya" in Avestan, the liturgical language of Zoroastrianism.[7]

Sat

[edit]Sat (Sanskrit: सत्) is the root of many Sanskrit words and concepts such as sattva ("pure, truthful") and satya ("truth"). The Sanskrit root sat has several meanings or translations:[8][9]

- "Absolute reality"

- "Fact"

- "Brahman" (not to be confused with Brahmin)

- "that which is unchangeable"

- "that which has no distortion"

- "that which is beyond distinctions of time, space, and person"

- "that which pervades the universe in all its constancy"

Sat is a common prefix in ancient Indian literature and implies variously that which is good, true, genuine, virtuous, being, happening, real, existing, enduring, lasting, or essential; for example, sat-sastra means true doctrine, sat-van means one devoted to the truth.[10]: 329–331 [8] In ancient texts, fusion words based on Sat refer to "Universal Spirit, Universal Principle, Being, Soul of the World, Brahman".[11][12]

The negation of sat is asat, meaning delusion, distorted, untrue, the fleeting impression that is incorrect, invalid, and false.[10]: 34 [8] The concepts of sat and asat are famously expressed in the Pavamana Mantra found in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (1.3.28):

Asato mā sad gamaya

tamaso mā jyotir gamaya

mṛtyor mā amṛtam gamaya

Lead me from delusion to truth

from darkness to light

from mortality to immortality

Sat is one of the three characteristics of Brahman as described in sat-chit-ananda.[12] This association between sat, 'truth', and Brahman, ultimate reality, is also expressed in Hindu cosmology, wherein Satyaloka, the highest heaven of Hindu cosmology, is the abode of Brahman.

Hinduism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

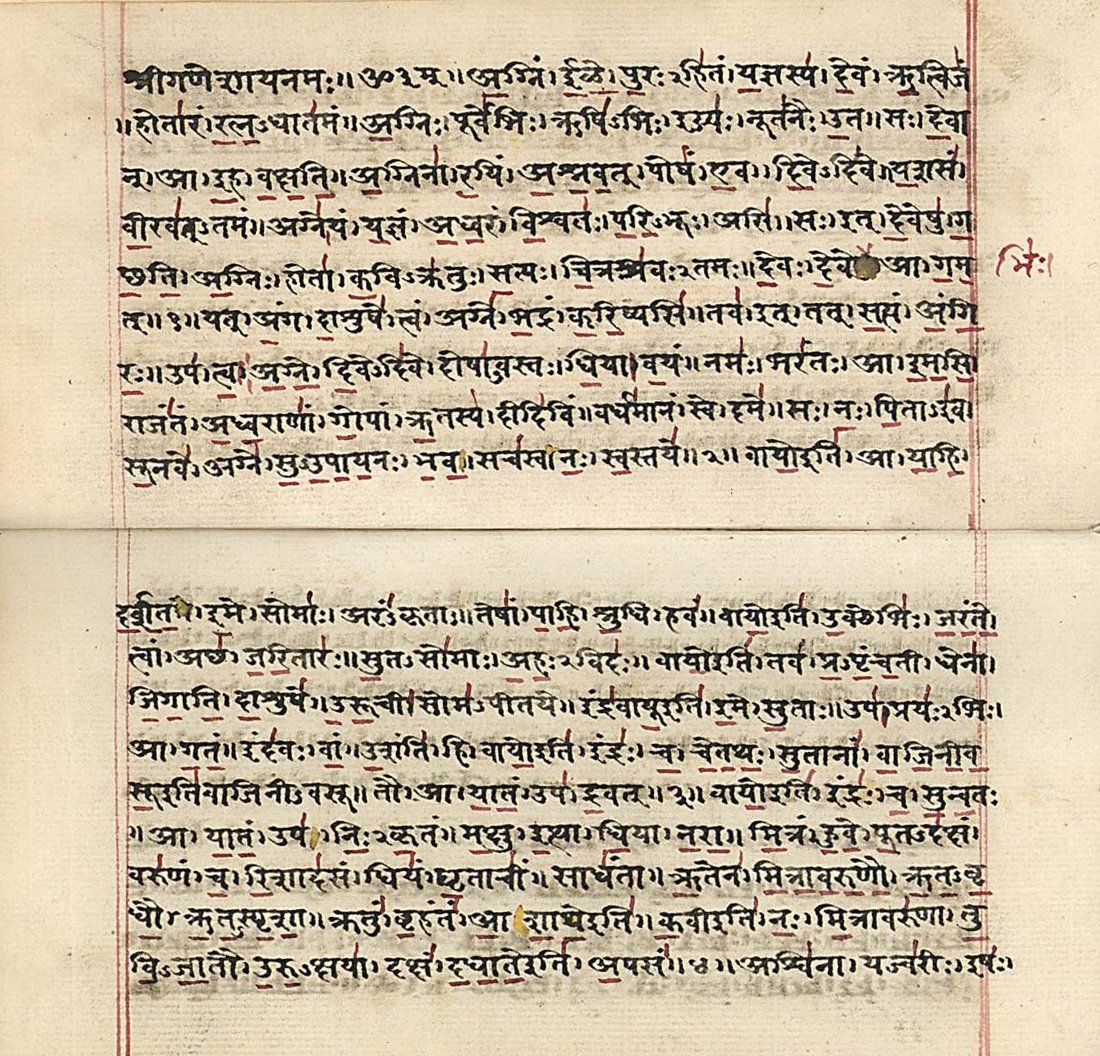

Vedic literature

[edit]Satya is a central theme in the Vedas. It is equated with and considered necessary to the concept Ṛta (ऋतं, ṛtaṃ)—that which is properly joined, order, rule, nature, balance, harmony.[1][13] Ṛta results from satya in the Vedas, as it[ambiguous] regulates and enables the operation of the universe and everything within it.[14] Satya is considered essential, and without it, the universe and reality falls apart, cannot function.[14]

In Rigveda, rita and satya are opposed to anrita and asatya (falsehood).[1] Truth and truthfulness is considered as a form of reverence for the divine, while falsehood a form of sin. Satya includes action and speech that is factual, real, true, and reverent to Ṛta in Books 1, 4, 6, 7, 9, and 10 of Rigveda.[2] However, in the Vedas satya encompasses one's current and future contexts in addition to one's past contexts.[clarification needed] De Nicolás[clarification needed] states, that in Rigveda, "Satya is the modality of acting in the world of Sat, as the truth to be built, formed or established".[2]

Upanishads

[edit]Satya is widely discussed in various Upanishads, including the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad where satya is called the means to Brahman, as well as Brahman (Being, true self).[15][16] In hymn 1.4.14 of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Satya (truth) is equated to Dharma (morality, ethics, law of righteousness),[17] as

Nothing is higher than the Law of Righteousness (Dharma). The weak overcomes the stronger by the Law of Righteousness. Truly that Law is the Truth (Satya); Therefore, when a man speaks the Truth, they say, "He speaks Righteousness"; and if he speaks Righteousness, they say, "He speaks the Truth!" For both are one.

Taittiriya Upanishad's hymn 11.11 states, "Speak the Satya (truth), conduct yourself according to the Dharma (morality, ethics, law)".[18][17]

Truth is sought, praised in the hymns of Upanishads, held as one that ultimately, always prevails. The Mundaka Upanishad, for example, states in Book 3, Chapter 1,[19]

— Mundaka Upanishad, 3.1.6[19]

Sandilya Upanishad of Atharvaveda, in Chapter 1, includes ten forbearances[24] as virtues, in its exposition of Yoga. It defines satya as "the speaking of the truth that conduces to the well being of creatures, through the actions of one's mind, speech, or body."[25]

Deussen states that satya is described in the major Upanishads with two layers of meanings—one as empirical truth about reality, another as abstract truth about universal principle, being, and the unchanging. Both of these ideas are explained in early Upanishads, composed before 500 BC, by variously breaking the word satya or satyam into two or three syllables. In later Upanishads, the ideas evolve and transcend into satya as truth (or truthfulness), and Brahman as the Being, Be-ness, real Self, the eternal.[26]

Epics

[edit]The Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata states, "The righteous hold that forgiveness, truth, sincerity, and compassion are the foremost (of all virtues). Truth is the essence of the Vedas."[27]

The Epic repeatedly emphasizes that satya is a basic virtue, because everything and everyone depends on and relies on satya.[28]

सत्यस्य वचनं साधु न सत्याद विद्यते परम

सत्येन विधृतं सर्वं सर्वं सत्ये परतिष्ठितम

अपि पापकृतॊ रौद्राः सत्यं कृत्वा पृथक पृथक

अद्रॊहम अविसंवादं परवर्तन्ते तदाश्रयाः

ते चेन मिथॊ ऽधृतिं कुर्युर विनश्येयुर असंशयम

To speak the truth is meritorious. There is nothing higher than truth. Everything is upheld by truth, and everything rests upon truth. Even the sinful and ferocious, swear to keep the truth amongst themselves, dismiss all grounds of quarrel and uniting with one another set themselves to their (sinful) tasks, depending upon truth. If they behaved falsely towards one another, they would then be destroyed without doubt.

Yoga Sutras

[edit]In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, it is written, “When one is firmly established in speaking truth, the fruits of action become subservient to him."[29] In Yoga sutra, satya is one of the five yamas, or virtuous restraints, along with ahimsa (restraint from violence or injury to any living being); asteya (restraint from stealing); brahmacharya (celibacy or restraint from sexually cheating on one's partner); and aparigraha (restraint from covetousness and craving). Patanjali considers satya as a restraint from falsehood in one's action (body), words (speech, writing), or feelings / thoughts (mind).[5][30] In Patanjali's teachings, one may not always know the truth or the whole truth, but one knows if one is creating, sustaining, or expressing falsehood, exaggeration, distortion, fabrication, or deception.[29] Satya is, in Patanjali's Yoga, the virtue of restraint from such falsehood, either through silence or through stating the truth without any form of distortion.[31]

Jainism

[edit]Satya is one of the five vows prescribed in Jain Agamas. Satya was also preached by Mahavira.[32] According to Jainism, not to lie or speak what is not commendable.[sentence fragment][33]: 61 The underlying cause of falsehood is passion and therefore, it is said to cause hiṃsā (injury).[33]: 66

According to the Jain text Sarvārthasiddhi: "that which causes pain and suffering to the living is not commendable, whether it refers to actual facts or not".[34]

According to the Jain text Puruşārthasiddhyupāya:[33]: 33

All these subdivisions (injury, falsehood, stealing, unchastity, and attachment) are hiṃsā as indulgence in these sullies the pure nature of the soul. Falsehood etc. have been mentioned separately only to make the disciple understand through illustrations.

— Puruşārthasiddhyupāya (42)

Buddhism

[edit]The term satya (Pali: sacca) is translated into English as "reality" or "truth." In terms of the Four Noble Truths (ariyasacca), the Pali can be written as sacca, tatha, anannatatha, and dhamma.

'The Four Noble Truths' (ariya-sacca) are the briefest synthesis of the entire teaching of Buddhism,[35][36] since all those manifold doctrines of the threefold Pali canon are, without any exception, included therein. They are the truth of suffering (mundane mental and physical phenomenon), of the origin of suffering (tanha, craving), of the extinction of suffering (Nibbana or nirvana), and of the Noble Eightfold Path leading to the extinction of suffering (the eight supra-mundane mind factors).[37]

Sikhism

[edit]| Sikh beliefs |

|---|

|

The Gurmukhs do not like falsehood; they are imbued with Truth; they love only Truth.

— Gurubani, Hymn 3, [38]

Sat or truthfulness is one of the 5 virtues in Sikhism.

Indian emblem motto

[edit]

The motto of the republic of India's emblem is Satyameva Jayate which is literally translated as 'Truth alone triumphs'.

See also

[edit]- Dharma – Key concept in Indian philosophy and Eastern religions, with multiple meanings

- Rta – Vedic principle of universal nature order

- Sacca

- Satnam – 'Satnam' was concept of Guru Nanak ji

- Satyaloka – Abode of the Hindu god Brahma

- Satya Yuga – First of four yugas (ages) in Hindu cosmology

- Transcendentals – Truth, beauty, and goodness

- Truth – Being in accord with fact or reality

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hindery, Roderick (1996). Comparative ethics in Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 51–55. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- ^ a b c de Nicolás, Antonio T. (2003). Meditations Through the Rig Veda. iUniverse. pp. 162–164. ISBN 978-0595269259.

- ^

- Macdonell, Arthur A. (1892). Sanskrit English Dictionary. Asian Educational Services. pp. 330–331. ISBN 9788120617797.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2003). "Hinduism, History of Science and Religion". In van Huyssteen, J. Wentzel Vrede; Howell, Nancy R.; Gregersen, Niels Henrik; Wildman, Wesley J.; Barbour, Ian; Valentine, Ryan (eds.). Encyclopedia of Science and Religion. Thomson Gale. p. 405. ISBN 0028657047.

- Macdonell, Arthur A. (1892). Sanskrit English Dictionary. Asian Educational Services. pp. 330–331. ISBN 9788120617797.

- ^ a b c Tiwari, Kedar Nath (1998). "Virtues and Duties in Indian Ethics". Classical Indian Ethical Thought. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 87. ISBN 978-8120816077.

- ^ a b Garg, Ganga Ram, ed. (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World. Vol. 3. Concept Publishing Company. p. 733. ISBN 8170223733.

- ^ Dhand, A. (2002). "The dharma of ethics, the ethics of dharma: Quizzing the ideals of Hinduism". Journal of Religious Ethics. 30 (3): 347–372. doi:10.1111/1467-9795.00113.

- ^

- Dept. of Classics and Ancient History, University of Auckland, ed. (1979). "Prudentia, Volumes 11–13". University of Auckland Bindery: 96.

The semantic connection may therefore be compared with the Sanskrit term for the 'moral law', dharma (cognate with Latin firmus) and 'truth' satya (cognate with English 'sooth' and Greek with its well known significance in Plato's thought...

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[verification needed] - Kahn, Charles H. (2009). Essays on Being. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0191560064.

A derivative of this participle still serves as the normal word for 'true' and 'truth' in languages so far apart as Danish sand and sandhed) and Hindi (sac, satya). In English we have a cognate form of this old Indo-European participle of 'to be' in 'sooth', 'soothsayer'.

- Russell, James R. (2009). "The rime of the Book of the Dove". In Allison, Christine; Joisten-Pruschke, Anke; Wendtland, Antje (eds.). From Daēnā to Dîn. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 186f105. ISBN 978-3447059176.

Av. haiθya-, from the verb 'to be'—truth in the sense of 'the way things actually are'—corresponds to its cognates, Skt. satyá-, Rus. istina.

- Dept. of Classics and Ancient History, University of Auckland, ed. (1979). "Prudentia, Volumes 11–13". University of Auckland Bindery: 96.

- ^ a b c Monier-Williams, Monier (1872). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 1052–1054.

- ^ Ishwaran, Karigoudar (1999). Ascetic Culture: Renunciation and Worldly Engagement. Leiden: Brill. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-90-04-11412-8.

- ^ a b Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (2004). A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary with Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis Throughout. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2000-5.

- ^ Chaudhuri, H. (1954). "The Concept of Brahman in Hindu Philosophy". Philosophy East and West. 4 (1): 47–66. doi:10.2307/1396951. JSTOR 1396951.

- ^ a b Aurobindo, Sri; Basu, Arabinda (2002). "The Sadhana of Plotinus". In Gregorios, Paulos (ed.). Neoplatonism and Indian Philosophy. Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press. pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-0-7914-5274-5.

- ^ Sourcebook of the world's religions: an interfaith guide to religion and spirituality. Novato, Calif.: New World Library. 2000. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-1-57731-121-8.

- ^ a b Holdrege, Barbara (2004). "Dharma". In Mittal, Sushil; Thursby, Gene R. (eds.). The Hindu world. New York: Routledge. p. 215. ISBN 0-415-21527-7.

- ^ Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. Translated by Madhavananda, Swami (third ed.). Advaita Ashrama. 1950. Section V.

- ^ a b Johnston, Charles (23 October 2014). The Mukhya Upanishads: Books of Hidden Wisdom. Kshetra. p. 481. ISBN 978-1495946530. For discussion on Satya and Brahman pp. 491–505, 561–575.

- ^ a b c Horsch, Paul (2004). "From Creation Myth to World Law: The early history of Dharma". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 32 (5–6). Translated by Whitaker, Jarrod: 423–448. doi:10.1007/s10781-004-8628-3. S2CID 170190727.

- ^ "taittirIya upanishad". Sanskrit Documents.

सत्यं वद । धर्मं चर, satyam vada dharmam cara

- ^ a b Easwaran, E. (2007). The Upanishads. Nilgiri Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-1586380212.

- ^ Mundaka Upanishad (Sanskrit) Wikisource

- ^ Ananthamurthy, U.R.; Mehta, Suketu; Ananthamurthy, Sharath (2008). "Compassionate Space". India International Centre Quarterly. 35 (2). India International Centre: 18–23. ISSN 0376-9771. JSTOR 23006353. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Lal, Brij (2011). A Vision for Change: Speeches and Writings of A.D. Patel 1929–1969. Australian National University Press. p. xxi. ISBN 978-1921862328.

- ^ Müller, F. Max, ed. (1884). "The Mundaka Upanishad". The Upanishads, Part 2. The Sacred Books of the East. Vol. XV. Translated by Müller, F. Max. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 38–40.

- ^ Patanjali states five restraints, rather than ten. The complete list of ten forbearances in Sandilya Upanishad are, in the order they are listed in original Upanishad manuscript: ahimsa, satya, asteya, brahmacharya, daya, arjava, kshama, dhrti, mitahara, and saucha

- ^ Narayanaswami Aiyar, K. (1914). Thirty minor Upanishads. Madras: V̇asanṭā Press. pp. 173–174. OCLC 23013613.

- ^ Deussen, Paul (1908). The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Translated by Geden, A.S. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. pp. 128–133.

- ^ Dutt, Manmatha Nath, ed. (1903). "Mokshadharma parva". The Mahābhārata: Shanti parva. CCC.12.

- ^ a b "Mokshadharma Parva". The Mahabharata, Vanti Parva, Volume II. Calcutta: Pratapa Chandra Ray, Bharata Press. 1891. p. 344.

- ^ a b Patanjali (September 2012). "Sutra Number 2.36". Yoga Sutras. Translated by Ravikanth, B. Sanskrit Works. pp. 140–150. ISBN 978-0988251502.

- ^ Palkhivala, Aadil (August 28, 2007). "Teaching the Yamas in Asana Class". Yoga Journal.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (19 April 2011). "Ahimsa in the Patanjali Yoga Tradition". In Rosen, Steven (ed.). Food for the Soul: Vegetarianism and Yoga Traditions. Praeger. pp. 33–48. ISBN 978-0313397035.

- ^

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2006) [1990]. Aspects of Jaina religion (5 ed.). Bharatiya Jnanpith. p. 67. ISBN 8126312734.

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (20 October 2023), Mahavira Jaina teacher, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b c Jain, Vijay K. (2012). Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation. Vikalp Printers. ISBN 978-8190363945.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ Jain, S.A. (1992) [1960], Reality (English Translation of Srimat Pujyapadacharya's Sarvarthasiddhi) (Second ed.), Jwalamalini Trust, p. 197,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ www.wisdomlib.org (2008-09-27). "Sacca, Saccā: 11 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 2025-01-17.

- ^ "Bauddha Darsana Lecture 6 Four Noble Truths" (PDF). Consortium for Educational Communication: 2.

- ^ "four noble truths". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ Sri Guru Granth Sahib page 23 Full Shabad