Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

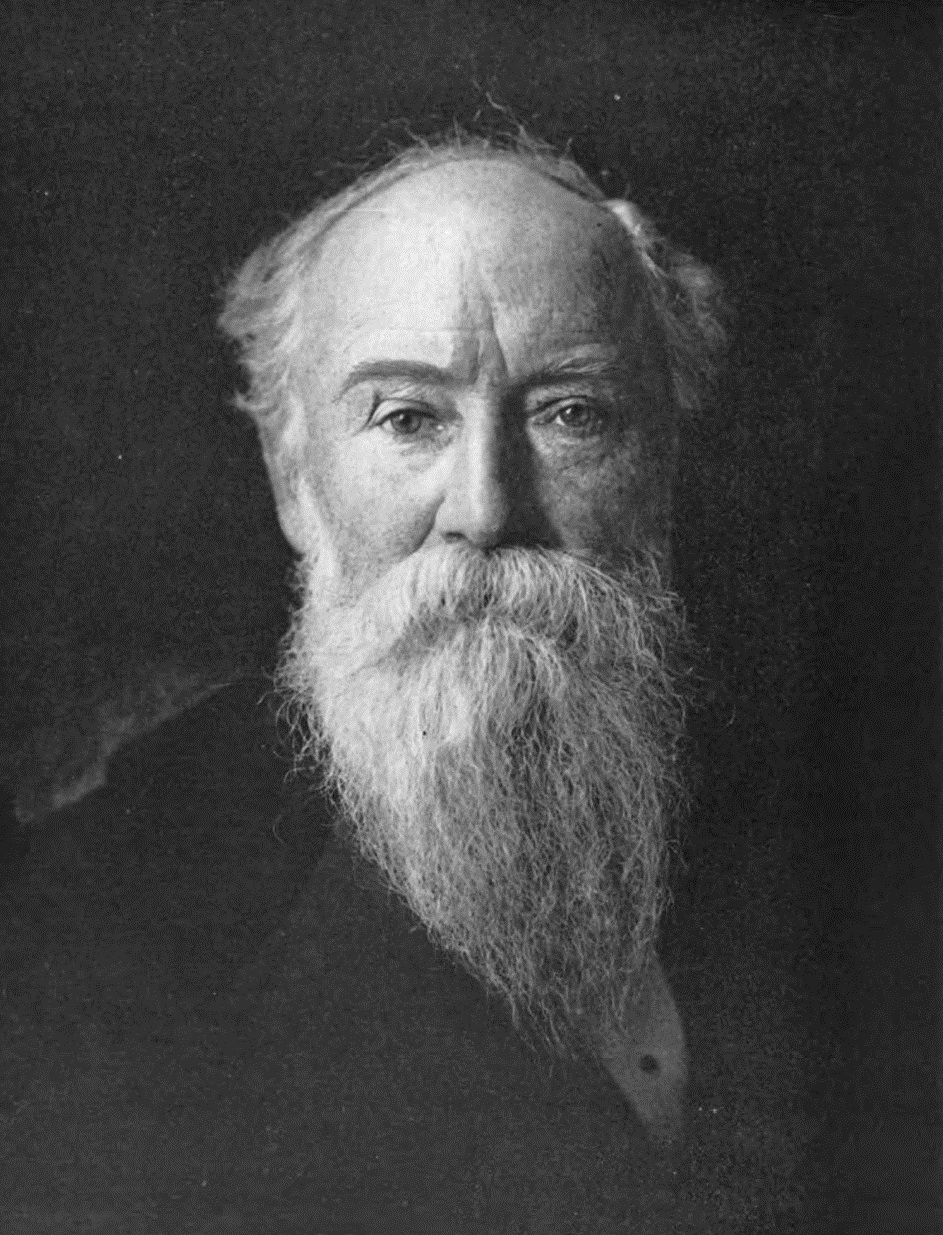

John Burroughs

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

John Burroughs (April 3, 1837 – March 29, 1921) was an American naturalist and nature essayist, active in the conservation movement in the United States.[1] The first of his essay collections was Wake-Robin in 1871.

In the words of his biographer Edward Renehan, Burroughs' special identity was less that of a scientific naturalist than that of "a literary naturalist with a duty to record his own unique perceptions of the natural world." The result was a body of work whose resonance with the tone of its cultural moment explains both its popularity at that time, and its relative obscurity since.[2]

Early life and marriage

[edit]Burroughs was the seventh of Chauncy and Amy Kelly Burroughs' ten children. He was born on the family farm in the Catskill Mountains, near Roxbury in Delaware County, New York. As a child he spent many hours on the slopes of Old Clump Mountain, looking off to the east and the higher peaks of the Catskills, especially Slide Mountain, which he would later write about. As he labored on the family farm he was captivated by the return of the birds each spring and other wildlife around the family farm including frogs and bumblebees. In his later years he credited his life as a farm boy for his subsequent love of nature and feeling of kinship with all rural things.[3]

During his teen years Burroughs showed a keen interest in learning.[4] Among Burroughs's classmates was future financier Jay Gould.[5] Burroughs' father believed the basic education provided by the local school was enough and refused to support the young Burroughs when he asked for money to pay for the books or the higher education he wanted. At the age of 17 Burroughs left home to earn funds needed for college by teaching at a school in Olive, New York.

From 1854 to 1856 Burroughs alternated periods of teaching with periods of study at higher education institutions including Cooperstown Seminary. He left the Seminary and completed his studies in 1856. He continued teaching until 1863. In 1857 Burroughs left a teaching position in the village of Buffalo Grove in Illinois to seek employment closer to home, drawn back by "the girl I left behind me."[3] On September 12, 1857, Burroughs married Ursula North (1836–1917). Burroughs later became an atheist with an inclination towards pantheism.[6]

Career

[edit]

Burroughs had his first break as a writer in the summer of 1860 when the Atlantic Monthly, then a fairly new publication, accepted his essay Expression. Editor James Russell Lowell found the essay so similar to Emerson's work that he initially thought Burroughs had plagiarized his longtime acquaintance. Poole's Index and Hill's Rhetoric, both periodical indexes, even credited Emerson as the author of the essay.[7]

In 1864, Burroughs accepted a position as a clerk at the Treasury; he would eventually become a federal bank examiner, continuing in that profession into the 1880s. All the while, he continued to publish essays, and grew interested in the poetry of Walt Whitman. Burroughs met Whitman in Washington, D.C., in November 1863, and the two became close friends.[8]

Whitman encouraged Burroughs to develop his nature writing as well as his philosophical and literary essays. In 1867, Burroughs published Notes on Walt Whitman as Poet and Person, the first biography and critical work on the poet, which was extensively (and anonymously) revised and edited by Whitman himself before publication.[9] Four years later, the Boston house of Hurd & Houghton published Burroughs's first collection of nature essays, Wake-Robin.

In January 1873, Burroughs left Washington for New York. The next year he bought a 9-acre (3.6 ha) farm in West Park, NY (now part of the Town of Esopus) where he built his Riverby estate. There he grew various crops before eventually focusing on table grapes. He continued to write, and continued as a federal bank examiner for several more years. In 1895 Burroughs bought additional land near Riverby where he and son Julian constructed an Adirondack-style cabin that he called "Slabsides". He wrote, grew celery, and entertained visitors there, including students from local Vassar College.[citation needed] After the turn of the 20th century, Burroughs renovated an old farmhouse near his birthplace and called it "Woodchuck Lodge." This became his summer residence until his death.

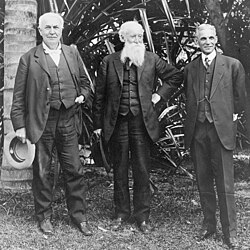

Burroughs accompanied many personalities of the time in his later years, including Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir, Henry Ford (who gave him an automobile, one of the first in the Hudson Valley), Harvey Firestone, and Thomas Edison. In 1899, he participated in E. H. Harriman's expedition to Alaska.

According to Ford, "John Burroughs, Edison, and I with Harvey S. Firestone made several vagabond trips together. We went in motor caravans and slept under canvas. Once, we gypsied through the Adirondacks and again through the Alleghenies, heading southward."[11]

In 1901, Burroughs met an admirer, Clara Barrus (1864–1931). She was a physician with the state psychiatric hospital in Middletown, New York. Clara was 37 and nearly half his age. She was the great love of his life[12] and ultimately his literary executrix. She moved into his house after Ursula died in 1917. She published Whitman and Burroughs: Comrades in 1931, relying on firsthand accounts and letters to documents Burroughs' friendship with poet Walt Whitman.

Nature fakers controversy

[edit]In 1903, after publishing an article entitled "Real and Sham Natural History" in the Atlantic Monthly, Burroughs began a widely publicized literary debate known as the nature fakers controversy. Attacking popular writers of the day such as Ernest Thompson Seton, Charles G. D. Roberts and William J. Long for their fantastical representations of wildlife, he also denounced the booming genre of "naturalistic" animal stories as "yellow journalism of the woods". The controversy lasted for four years and involved American environmental and political figures of the day, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who was friends with Burroughs.[13]

Writing

[edit]Many of Burroughs' essays first appeared in popular magazines. He is best known for his observations on birds, flowers and rural scenes, but his essay topics also range to religion, philosophy, and literature. Burroughs was a staunch defender of Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, but somewhat critical of Henry David Thoreau, even while praising many of Thoreau's qualities.[citation needed] His achievements as a writer were confirmed by his election as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[14]

Some of Burroughs' essays came out of trips back to his native Catskills. In the late 1880s, in the essay "The Heart of the Southern Catskills," he chronicled an ascent of Slide Mountain, the highest peak of the Catskills range. Speaking of the view from the summit, he wrote: "The works of man dwindle, and the original features of the huge globe come out. Every single object or point is dwarfed; the valley of the Hudson is only a wrinkle in the earth's surface. You discover with a feeling of surprise that the great thing is the earth itself, which stretches away on every hand so far beyond your ken." The first sentence of this quote is now on a plaque commemorating Burroughs at the mountain's summit, on a rock outcrop known as Burroughs Ledge. Slide and neighboring Cornell and Wittenberg mountains, which he also climbed, have been collectively named the Burroughs Range.

Other Catskill essays told of fly fishing for trout, of hikes over Peekamoose Mountain and Mill Brook Ridge, and of rafting down the East Branch of the Delaware River. It is for these that he is still celebrated in the region today, and chiefly known, although he traveled extensively and wrote about other regions and countries, as well as commenting on natural-science controversies of the day such as the theory of natural selection.[15] He entertained philosophical and literary questions, and wrote another book about Whitman in 1896, four years after the poet's death.

Fishing

[edit]From his youth, Burroughs was an avid fly fisherman and known among Catskill anglers.[16] Although he never wrote any purely fishing books, he did contribute some notable fishing essays to angling literature. Most notable of these was Speckled Trout, which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in October 1870 and was later published in In The Catskills. In Speckled Trout, Burroughs highlights his experiences as an angler and celebrates the trout, streams and lakes of the Catskills.[17]

Death

[edit]

Burroughs enjoyed good physical and mental health during his later years until only a few months before his death when he began to experience lapses in memory and show general signs of advanced age including declining heart function. In February 1921, Burroughs underwent an operation to remove an abscess from his chest. After this operation, his health steadily declined. Burroughs died on March 29, 1921, on a train near Kingsville, Ohio.[1] He was buried in Roxbury, New York, on what would have been his 84th birthday, at the foot of a rock he had played on as a child and affectionately referred to as "Boyhood Rock". A line of his is etched on the rock: "I stand amid the eternal ways".[18]

Legacy

[edit]Woodchuck Lodge was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1962. Riverby and Slabsides were similarly designated in 1968. All three are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Thirteen U.S. schools have been named for Burroughs, including public elementary schools in Washington, D.C.; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and Minneapolis, Minnesota; public middle schools in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Los Angeles; a public high school in Burbank, California, and a private secondary school, John Burroughs School, in St. Louis, Missouri. Burroughs Mountain in Mount Rainier National Park is named in his honor, as is Burroughs Creek in St. Louis County, Missouri.[19]

The John Burroughs Association was founded after his death to commemorate his life and works. It maintains the John Burroughs Sanctuary in West Park, New York, a 170-acre plot of land surrounding Slabsides, and awards a medal each year to "the author of a distinguished book of natural history".[20][21]

Another award bearing Burroughs name is available to Boy Scouts who attend Seven Ranges Scout Reservation in Kensington, Ohio. The requirements to achieve this award require ample knowledge in the field of plants, rocks and minerals, astronomy, and animals. The award has three levels: bronze, gold, and silver being the highest. Each level requires more knowledge in the given fields.[citation needed]

Famous quotes

[edit]- "The Kingdom of heaven is not a place, but a state of mind."

- "Leap, and the net will appear."[citation needed]

- "A man can fail many times, but he isn't a failure until he begins to blame somebody else."

Works

[edit]The Complete Writings of John Burroughs totals 23 volumes. The first volume, Wake-Robin, was published in 1871 and subsequent volumes were published regularly until the final volume, The Last Harvest, was published in 1922. The final two volumes, Under the Maples and The Last Harvest, were published posthumously by Clara Barrus. Burroughs also published a biography of John James Audubon, a memoir of his camping trip to Yellowstone with President Theodore Roosevelt, and a volume of poetry titled Bird and Bough.

- Notes on Walt Whitman as Poet and Person (1867)

- Wake Robin (1871)

- Winter Sunshine (1875)

- Birds and Poets (1877)

- Locusts and Wild Honey (1879)

- Pepacton (1881)

- Fresh Fields (1884)

- Signs and Seasons (1886)

- Birds and bees and other studies in nature (1896)

- Indoor Studies (1889)

- Riverby (1894)

- Whitman: A Study (1896)

- The Light of Day (1900)

- Squirrels and Other Fur-Bearers (1900)

- Songs of Nature (Editor) (1901)

- John James Audubon (1902)

- Literary Values and other Papers (1902)

- Far and Near (1904)

- Ways of Nature (1905)

- Camping and Tramping with Roosevelt (1906)

- Bird and Bough (1906)

- Afoot and Afloat (1907)

- Leaf and Tendril (1908)

- Time and Change (1912)

- The Summit of the Years (1913)

- The Breath of Life (1915)

- Under the Apple Trees (1916)

- Field and Study (1919)

- Accepting the Universe (1920)

- Under the Maples (1921)

- The Last Harvest (1922)

- My Boyhood, with a Conclusion by His Son Julian Burroughs (1922)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "John Burroughs Dies On A Train. Famous Naturalist's Last Words Were: "How Far Are We From Home?" Was Returning From West. Body Taken to His Rural Retreat. Henry Ford and Others Pay High Tribute to Him" (PDF). New York Times. March 30, 1921. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

John Burroughs, the world-renowned naturalist, died suddenly at 2 o'clock this morning on a New York Central passenger train near Kingsville, Ohio. His body lies tonight in his home by the banks of the Hudson River a few miles north of this city.

- ^ Renehan, Edward (1998), John Burroughs: An American Naturalist, Black Dome Press, ISBN 978-1883789169

- ^ a b Clara Barrus (1914). Our Friend John Burroughs. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780838311691.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Barrus, Clara (1968). The Life and Letters of John Burroughs. New York: Russell & Russell. p. 28.

- ^ Renehan, Edward J. Jr. (2005). Dark Genius of Wall Street: The Misunderstood Life of Jay Gould, King of the Robber Barons. New York: Basic Books. pp. 17.

- ^ Dan Barker (2011). The Good Atheist: Living a Purpose-Filled Life Without God. Ulysses Press. p. 170. ISBN 9781569758465. An essayist who popularized the American romantic view of nature, Burroughs wrote, “When I look up at the starry heavens at night and reflect upon what is it that I really see there, I am constrained to say, 'There is no God.'" In his 1910 journal, he wrote: "Joy in the universe, and keen curiosity about it all-that has been my religion."

- ^ Barrus, Clara (1968). The Life and Letters of John Burroughs. New York: Russell & Russell. p. 52.

- ^ Peck, Garrett (2015). Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 83–85. ISBN 978-1626199736.

- ^ Peck, Garrett (2015). Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1626199736.

- ^ "Slabsides (John Burroughs cabin)". National Historic Landmark listing. National Park Service. September 11, 2007. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012.

- ^ Ford, Henry (2019). My Life and Work. Columbia. p. 116. ISBN 9781545549117.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia, ed. J.R. LeMaster, p. 90: "Burroughs and Ursula", Carmine Sarracino, pub. Routledge, 1998

- ^ Carson, Gerald. February 1971. "T.R. and the 'nature fakers'" Archived November 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. American Heritage. Volume 22, Issue 2.

- ^ "Academy Honors John Burroughs; Naturalist Praised by Bliss Perry and Hamlin Garland at Memorial Meeting," New York Times. November 19, 1921.

- ^ New York Times December 17, 1922: John Burroughs' last book by Hildegarde Hawthorne.

- ^ Karas, Nick (1997). Brook Trout: a Thorough Look At North America's Great Native Trout – its History, Biology and Angling Possibilities. New York: Lyons & Burford. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-1-55821-479-8.

- ^ Burroughs, John (1910). In the Catskills. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 187–219.

- ^ Barrus, Clara (1925). The Life and Letters of John Burroughs Vol. II. Cambridge: Riverside Press. p. 417.

- ^ "2010 tributaries naming project". Deer Creek Watershed Alliance. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ JBA Medal Award List Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on December 11, 2009

- ^ "Home". www.johnburroughsassociation.org. Retrieved October 7, 2025.

Further reading

[edit]Works about John Burroughs

- Our Friend John Burroughs by Clara Barrus (Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1914)

- John Burroughs Boy and Man by Clara Barrus (Garden City New York Doubleday, Page & Company, 1920)

- The Life and Letters of John Burroughs by Clara Barrus (Volume 1, Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1925)

- The Life and Letters of John Burroughs by Clara Barrus (Volume 2, Cambridge, Massachusetts, The Riverside Press, Copyright, 1925)

- The Edge of April: A Biography of John Burroughs by Hildegarde Hoyt Swift. Illustrated by Lynd Ward. (Wm Morrow & Co., New York, copyright 1957)

- John Burroughs: Naturalist by Elizabeth Burroughs Kelley (Exposition Press Inc., 386 Fourth Avenue, New York 16, NY, copyright 1959)

- John Burroughs by Perry D Westbrook (Twayne Publishers, New York, 1974)

- The Birds of John Burroughs: Keeping a Sharp Lookout edited by Jack Kligerman (Hawthorn Books, 1976)

- John Burroughs: An American Naturalist by Edward J. Renehan Jr. (Chelsea, VT: Chelsea Green, 1992; paperback – Hensonville, NY: Black Dome Press, 1998)

- John Burroughs: The Sage of Slabsides by Ginger Wadsworth (Clarion Books, 1997)

- Sharp Eyes: John Burroughs and American Nature Writing edited by Charlotte Zoe Walker, ed. (Syracuse University Press, 2000)

- The Art Of Seeing Things by John Burroughs edited by Charlotte Zoe Walker, ed. (Syracuse University Press, 2001)

- John Burroughs and The Place of Nature by James Perrin Warren (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2006)

- American Journey: On the Road With Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and John Burroughs by Wes Davis (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2023)

External links

[edit]- Works by John Burroughs at Project Gutenberg

- Works by John Burroughs at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about John Burroughs at the Internet Archive

- Works by John Burroughs at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1919 silent film "A Day With John Burroughs"

- The John Burroughs Association

- John Burroughs' Woodchuck Lodge

- John Burroughs page at the Catskill Archive

- American Memory In the Catskills

- Quotes

- Afterword to John Burroughs: An American Naturalist by Edward J. Renehan Jr.

- The Half More Satisfying Than the Whole: John Burroughs and the Hudson by Edward J. Renehan Jr.

- John Burroughs Postcard Collection

- Rediscovering John Burroughs' Catskills Retreat: Woodchuck Lodge by Edward J. Renehan Jr.

- Bird and Bough by John Burroughs. Complete text of his only book of published poems plus poems published in periodicals; also public domain recordings of his poems.

- Quotes by John Burroughs Archived March 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Papers of John Burroughs at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia

- Correspondence by Burroughs to and about Walt Whitman in the Walt Whitman collection, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

John Burroughs

View on GrokipediaJohn Burroughs (April 3, 1837 – March 29, 1921) was an American naturalist, essayist, and early advocate for conservation whose writings emphasized intimate observation of the natural world.[1][2] Born on a farm in Roxbury, New York, to farming parents Chauncey Burroughs and Amy Kelly, he drew from his rural upbringing to craft essays that celebrated the Catskills' landscapes, birds, and seasonal changes, beginning with his debut collection Wake-Robin in 1871.[3][4] Over his career, Burroughs published more than 23 volumes of prose, prioritizing experiential insights into ecology over taxonomic detail, which helped foster public appreciation for wilderness preservation amid rapid industrialization.[5] Regarded as one of America's foremost naturalists alongside figures like John Muir and Henry David Thoreau, his work influenced policy leaders, including President Theodore Roosevelt, with whom he shared camping trips that reinforced commitments to national parks and wildlife protection.[6] Burroughs' legacy endures in his role bridging literary nature writing and practical environmentalism, authoring pieces that urged readers to engage directly with untamed habitats rather than mediated scientific reports.[7]