Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

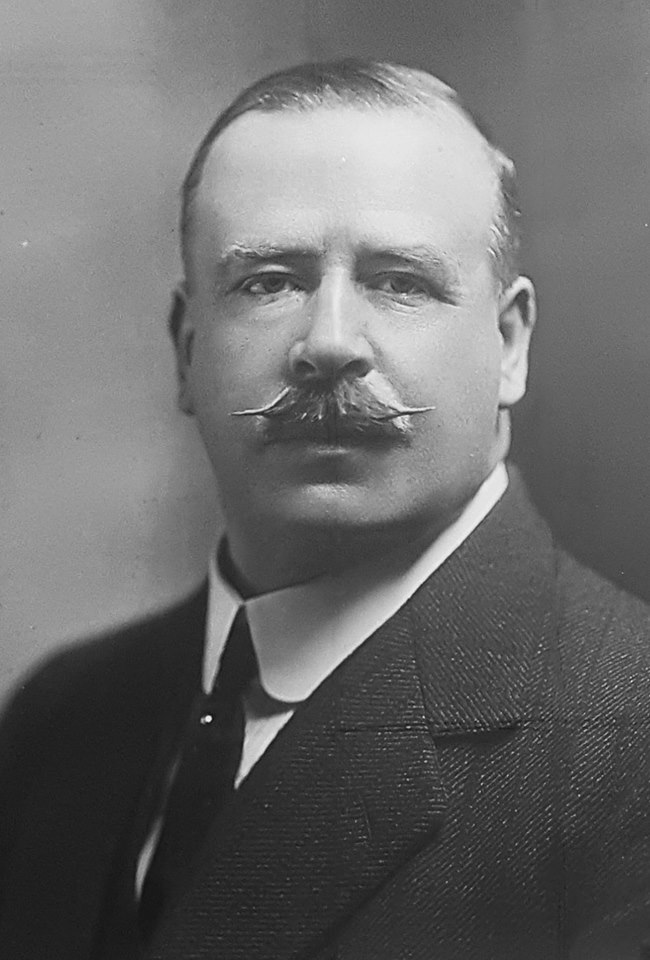

Joseph Ward

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

Sir Joseph George Ward, 1st Baronet, GCMG, PC (26 April 1856 – 8 July 1930) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 17th prime minister of New Zealand from 1906 to 1912 and from 1928 to 1930. He was a dominant figure in the Liberal and United ministries of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Key Information

Ward was born into an Irish Catholic family in Melbourne, Victoria. In 1863, financial hardship forced his family to move to New Zealand, where he completed his education. Ward established a successful grain trade in Invercargill in 1877 and soon became prominent in local politics. He became a Member of Parliament in 1887. Following the election of the Liberal Government in 1891, Ward was appointed as Postmaster-General under John Ballance; he was promoted to Minister of Finance in the succeeding ministry of Richard Seddon.

Ward became Prime Minister on 6 August 1906, following Seddon's death two months earlier. In his first period of government, Ward advocated greater unity within the British Empire, led New Zealand to Dominion status, and increased New Zealand's contribution to the Royal Navy. His government faced strong opposition from the Reform Party and the newly formed socialist parties. He led the Liberal Party to two election victories, in 1908 and 1911, albeit with a one-seat majority in the latter. He resigned as head of government on 28 March 1912.

During the First World War, Ward led his party in a coalition with the Reform Party. As co-leader of the government, Ward had a strained working relationship with Prime Minister William Massey. The coalition was dissolved in 1919 and Ward resigned as Liberal leader.

After a six-year absence from national politics, Ward returned to parliament in 1925. He became Prime Minister on 10 December 1928, as leader of the United Party, which had formed from the remnants of the former Liberal Party. Ward attempted to rejuvenate liberal support in New Zealand but his party lost ground to the New Zealand Labour Party. Failing health forced his retirement from leadership on 28 May 1930.

Early life

[edit]

Ward was born in Melbourne on 26 April 1856 to a Roman Catholic family of Irish descent. His father, William, died in 1860, aged 31 – Ward was raised by his mother, successful businesswoman Hannah Ward Barron. In 1863, the family moved to Bluff (then officially known as Campbelltown), in New Zealand's Southland region, seeking better financial security – Hannah Ward Barron established a shop and a boarding house.[1]

Ward received his formal education at primary schools in Melbourne and Bluff. He did not go to secondary school. He did, however, read extensively, and also picked up a good understanding of business from his mother. In 1869, Ward found a job at the Post Office, and later as a clerk. Later, with the help of a loan from his mother, Ward began to work as a freelance trader, selling supplies to the newly established Southland farming community.[1]

Early political career

[edit]| Years | Term | Electorate | Party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1887–1890 | 10th | Awarua | Independent | ||

| 1890–1893 | 11th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1893–1896 | 12th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1896–1897 | 13th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1897–1899 | 13th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1899–1902 | 14th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1902–1905 | 15th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1905–1908 | 16th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1908–1911 | 17th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1911–1914 | 18th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1914–1919 | 19th | Awarua | Liberal | ||

| 1925–1928 | 22nd | Invercargill | Liberal | ||

| 1928 | Changed allegiance to: | United | |||

| 1928–1930 | 23rd | Invercargill | United | ||

Ward became involved in local politics very quickly. He was elected to the Campbelltown (Bluff) Borough Council in 1878, despite being only 21 years old – at age 25 he became Mayor, the youngest in New Zealand. He also served on the Bluff Harbour Board, eventually becoming its chairman. In 1887, Ward stood for Parliament, winning the seat of Awarua.[2] Politically, Ward was a supporter of politicians such as Julius Vogel and Robert Stout, leaders of the liberal wing of Parliament – Ward's support was unusual in the far south.[citation needed]

Ward became known as a strong debater on economic matters. In 1891, when the newly founded Liberal Party came to power, the new Prime Minister, John Ballance, appointed Ward as Postmaster General. Later, when Richard Seddon became Prime Minister after Ballance's death, Ward became Treasurer (Minister of Finance). Ward's basic political outlook was that the state existed to support and promote private enterprise, and his conduct as Treasurer reflects this.[3]

Ward's increasing occupation with government affairs led to neglect of his own business interests, however, and his personal finances began to deteriorate. In 1896, a judge declared Ward "hopelessly insolvent". This placed Ward, as Treasurer, in a politically difficult situation, and he was forced to resign his portfolios on 16 June. In 1897, he was forced to file for bankruptcy, which legally obligated him to resign his seat in Parliament. A loophole meant that there was nothing to stop him contesting it again, however. In the resulting by-election he was elected with an increased majority. Ward gained considerable popularity as a result of his financial troubles – he was widely seen as a great benefactor of the Southland region, and public perceptions were that he was being persecuted by his enemies over an honest mistake.[citation needed]

Gradually, Ward rebuilt his businesses, and paid off his creditors. Seddon, still Prime Minister, quickly reappointed him to Cabinet where he served as Minister of Railways and Postmaster-General. On 19 June 1901, on the occasion of the visit of TRH the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York (later King George V and Queen Mary) to New Zealand, he was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) for overseeing the introduction of the Penny Post throughout New Zealand.[4][5]

Ward gradually emerged as the most prominent of Seddon's supporters, and was seen as a possible successor. As Seddon's long tenure as Prime Minister continued, some suggested that Ward should challenge Seddon for the leadership, but Ward was unwilling. In 1906, Seddon unexpectedly died. Ward was in London at the time. It was generally agreed in the party that Ward would succeed him, although the return journey would take two months – William Hall-Jones became Prime Minister until Ward arrived. Ward was sworn in on 6 August 1906.[1]

Canada: "Rather large for him, is it not?"

Australia: "Oh his head is swelling rapidly. The hat will soon fit."

First premiership

[edit]

Ward was not seen by most as being of the same calibre as Seddon. The diverse interests of the Liberal Party, many believed, had been held together only by Seddon's strength of personality and his powers of persuasion – Ward was not seen as having the same qualities.[6] Frequent internal disputes led to indecision and frequent policy changes, with the result being paralysis of government.

The Liberal Party's two main support bases, left-leaning urban workers and conservative small farmers, were increasingly at odds, and Ward lacked any coherent strategy to solve the problem – any attempt to please one group simply alienated the other. Ward increasingly focused on foreign affairs, which was seen by his opponents as a sign that he could not cope with the country's problems.[1]

In 1901, Ward established the world's first Ministry of Health and Tourism, and became the British Empire's first Minister of Public Health.[1] On 26 September 1907, Ward proclaimed New Zealand's new status as a Dominion.[7] He presided over a period of economic prosperity and provided state funds to help new settlers to the country. Public works schemes continued under his government with new infrastructure being built.[6]

In the 1908 election the Liberals won a majority, but in the 1911 election Parliament appeared to be deadlocked. The Liberals survived for a time on the casting vote of the Speaker, but Ward, discouraged by the result, resigned from the premiership in March the following year. The party replaced him with Thomas Mackenzie, his Minister of Agriculture, whose government survived only a few more months.[8]

Ward, who most believed had finished his political career, returned to the back benches and refused several requests to resume the leadership of the disorganised Liberals. He occupied himself with relatively minor matters, and took his family on a visit to England, where he was created a baronet by King George V on 20 June 1911.[9]

Leader of the Opposition

[edit]

On 11 September 1913, however, Ward finally accepted the leadership of the Liberal Party once again.[10] Ward extracted a number of important concessions from the party, insisting on a very high level of personal control – he felt that the party's previous lack of direction was the primary cause for its failure. He also worked to build alliances with the growing labour movement, which was now standing candidates in many seats. Ward lead the Liberals into the 1914 election and gained two seats. Despite the gains the Reform government was reduced to a bare minimum majority and when a by-election in Dunedin Central was triggered early the next year there was much at stake. The Liberal Party chose not contest the election themselves but Ward actively toured the electorate holding meetings to encourage the electors to vote for the Labour candidate Jim Munro. In the event of a Labour victory it was conceivable for Ward to form a minority government with Labour support. Ward had made preparation for a return to power, but the Reform Party managed to hold the seat.[11]

On 12 August 1915, Ward and accepted a proposal by William Massey and the governing Reform Party to form a joint administration for World War I. Ward became deputy leader of the administration, also holding the Finance portfolio. Relations between Ward and Massey were not good – besides their political differences, Ward was an Irish Catholic, and Massey was an Irish Protestant. The administration ended on 21 August 1919 following a decision made by caucus to do so two months earlier.[12]

In the 1919 election Ward lost the seat of Awarua, and left Parliament. In 1923, he contested a by-election in Tauranga, but was defeated by a Reform Party candidate, Charles Macmillan.[13] Ward was largely considered a spent force. In the 1925 election, however, he narrowly returned to Parliament as MP for Invercargill.[2] Ward contested the seat under the "Liberal" label, despite the fact that the remnants of the Liberal Party were now calling themselves by different names – his opponents characterised him as living in the past, and of attempting to fight the same battles over again. Ward's health was also failing.

In 1928 the remnants of the Liberal Party reasserted themselves as the new United Party, focused around George Forbes (leader of one faction of the Liberals), Bill Veitch (leader of another faction), and Albert Davy (a former organiser for the Reform Party). Forbes and Veitch both sought the leadership, and neither gained a clear advantage. Davy invited Ward to step in as a compromise candidate, perhaps hoping that Ward's status as a former Prime Minister would create a sense of unity.

Second premiership

[edit]

Ward accepted an offer from Albert Davy and became leader of the new United Party, fighting off three other contenders.[14] His health, however, was still poor, and he found the task difficult. In the 1928 election campaign, Ward startled both his supporters and his audience by promising to borrow £70 million in the course of a year to revive the economy – this is believed to have been a mistake caused by Ward's failing eyesight. Despite the strong objections his party had to this "promise", it was sufficient to prompt a massive surge in support for United – in the election United gained the same number of seats as Reform.

With the backing of the Labour Party, Ward became Prime Minister again, 22 years after his original appointment. He also briefly served as Minister of External Affairs in 1929.[15] Ward was also attempting to rejuvenate liberal support in New Zealand. His cabinet was rather youthful, with only two members (Thomas Wilford and Āpirana Ngata), other than himself, having held ministerial portfolios before.[16] Ward, as Finance Minister, passed a mini-budget at the end of 1928 appropriating £1,175,000 for public works construction.[17] In 1929 the government reneged on the £70 million borrowing promise and introduced a watered down land tax. In October, under increasing pressure from Labour, Ward made moves to reduce the growing unemployment numbers.[18]

Health and death

[edit]

Ward's health continued to decline. From late-September 1929 Ward seldom attended debates in the House and from March 1930 Ward was too ill to even hold meetings of the Cabinet.[19] He suffered a number of heart attacks, and soon it was George Forbes who was effectively running the government. Ward was determined not to resign, and remained Prime Minister until well after he had lost the ability to perform the role effectively. On 28 May 1930, Ward succumbed to strong pressure from his colleagues and his family, and passed the premiership to Forbes.[20] Ward had been promoted to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George in the 1930 New Year Honours.[21]

Ward remained a member of the cabinet as a Minister without Portfolio, but died shortly afterwards, on 8 July. He was given a state funeral with a Requiem Mass celebrated on 9 July at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hill St, Wellington. Ward had been an active worshipper there (and at its destroyed predecessor, St Mary's Cathedral) for all of his thirty-seven years as an MP.[22]

The Mass was celebrated by Bishop O'Shea (the Coadjutor Archbishop of Wellington), and Archbishop Redwood, 1st Archbishop of Wellington, delivered the panegyric.

Ward was buried with considerable ceremony in Bluff. His son Vincent was elected to replace him as MP for Invercargill.[1]

Arms

[edit]

|

|

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Bassett, Michael. "Ward, Joseph George". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ a b Wilson 1985, p. 243.

- ^ Foster 1966.

- ^ "No. 27325". The London Gazette. 21 June 1901. p. 4182.

- ^ Profile, Firstworldwar.com; accessed 21 October 2014.

- ^ a b Frykberg, Eric (8 November 2024). "The real power list: NZ's Prime Ministers rated". New Zealand Listener. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ "Joseph Ward proclaims Dominion status – 26 September 1907". New Zealand History online. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- ^ Bassett 1982, p. 11.

- ^ "No. 28577". The London Gazette. 2 February 1912. p. 797.

- ^ Bassett 1993, p. 219.

- ^ Bassett 1982, p. 18.

- ^ Bassett 1993, p. 243.

- ^ Bassett 1993, p. 255.

- ^ Bassett 1993, p. 264.

- ^ New Zealand Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 223 (1929).

- ^ Bassett 1993, p. 271.

- ^ Bassett 1982, p. 88.

- ^ Bassett 1982, p. 51.

- ^ Bassett 1982, p. 52.

- ^ Bassett 1993, p. 282.

- ^ "New year honours". Timaru Herald. 2 January 1930. p. 8. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Bassett 1993, pp. 283–4.

- ^ Burke's Peerage. 1949.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bassett, Michael (1982). Three Party Politics in New Zealand 1911–1931. Auckland: Historical Publications. ISBN 0-86870-006-1.

- Bassett, Michael (1993). Sir Joseph Ward: A Political Biography. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Foster, Bernard John (1966). "Ward, Sir Joseph George". In McLintock, A. H. (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Loughnan, Robert Andrew (1929). The Remarkable Life Story of Sir Joseph Ward: 40 Years a Liberal. New Century Press.

- Wilson, Jim (1985) [First published in 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1984 (4th ed.). Wellington: V.R. Ward, Govt. Printer. OCLC 154283103.