Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nimrud

View on WikipediaNimrud (/nɪmˈruːd/; Syriac: ܢܢܡܪܕ Arabic: النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city (original Assyrian name Kalḫu, biblical name Calah) located in Iraq, 30 kilometres (20 mi) south of the city of Mosul, and 5 kilometres (3 mi) south of the village of Selamiyah (Arabic: السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a major Assyrian city between approximately 1350 BC and 610 BC. The city is located in a strategic position 10 kilometres (6 mi) north of the point that the river Tigris meets its tributary the Great Zab.[1] The city covered an area of 360 hectares (890 acres).[2] The ruins of the city were found within one kilometre (1,100 yd) of the modern-day Assyrian village of Noomanea in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq.

Key Information

The name Nimrud was recorded as the local name by Carsten Niebuhr in the mid-18th century.[3][note 1] In the mid 19th century, biblical archaeologists proposed the Assyrian name Kalḫu (the Biblical Calah), based on a description of the travels of Nimrod in Genesis 10.[note 2]

Archaeological excavations at the site began in 1845, and were conducted at intervals between then and 1879, and then from 1949 onwards. Many important pieces were discovered, with most being moved to museums in Iraq and abroad. In 2013, the UK's Arts and Humanities Research Council funded the "Nimrud Project", directed by Eleanor Robson, whose aims were to write the history of the city in ancient and modern times, to identify and record the dispersal history of artefacts from Nimrud,[4] distributed amongst at least 76 museums worldwide (including 36 in the United States and 13 in the United Kingdom).[5]

In 2015, the terrorist organization Islamic State announced its intention to destroy the site because of its "un-Islamic" Assyrian nature. In March 2015, the Iraqi government reported that Islamic State had used bulldozers to destroy excavated remains of the city. Several videos released by ISIL showed the work in progress. In November 2016, Iraqi forces retook the site, and later visitors also confirmed that around 90% of the excavated portion of city had been completely destroyed. The ruins of Nimrud have remained guarded by Iraqi forces ever since.[6] Reconstruction work is in progress.

History

[edit]

Kalhu was located on a prosperous route and was built of an earlier business community under Shalmaneser I in the 13th century BC. Through the centuries, it was in disrepair.[8] In the 9th century BC Ashurnasirpal II ordered the removal of debris from the towers and walls and began the construction of a capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This city would have a royal mansion of superior size, larger than previous monarchs'.[9]

In addition to enormous city walls 7.5 kilometers (4.6 miles) long, palaces, temples, royal offices and various residential buildings, Ashurnasirpal also established botanical gardens, filled with foreign plants brought back from his wide-ranging campaigns, and a zoo, perhaps the first large zoo ever constructed.[10] Ashurnasirpal's inscriptions offer no motive for changing the capital. Various explanations have been proposed by modern scholars, including that he might have gotten disenchanted with Assur since there was little room left in the ancient capital to leave a mark,[10] the important position of Nimrud in regard to local trade networks,[10] that Nimrud was more centrally located in the empire,[11] or that Ashurnasirpal hoped for greater independence from the influential great families of Assur.[11]

A grand opening ceremony with festivities and an opulent banquet in 864 BC is described in an inscribed stele discovered during archeological excavations.[12] To celebrate the completion of his work in Nimrud in 864 BC, Ashurnasirpal hosted a grand celebration,[11] which some scholars have described as perhaps the greatest party in world history;[10] the event hosted 69,574 guests, including 16,000 citizens of the new capital and 5,000 foreign dignitaries, and lasted for ten days. Among the food and beverage used, Ashurnasirpal's inscriptions record 10,000 pigeons, 10,000 jugs of beer, and 10,000 skins of wine, among countless other items.[11]

By 800 BC Nimrud had grown to 75,000 inhabitants making it the largest city in the world.[13][14] The kings of Assyria continued to be buried in Assur, but their queens were buried in Kalhu. Kalhu is known today as Nimrud because the archaeologists of the 19th and 20th centuries gave it that name, believing it was the legendary city of the biblical Nimrod, which is mentioned in the Book of Genesis.[15]

King Ashurnasirpal's son Shalmaneser III (858–823 BC) continued where his father had left off. At Nimrud he built a palace that far surpassed his father's. It was twice the size and it covered an area of about 5 hectares (12 acres) and included more than 200 rooms.[16] He built the monument known as the Great Ziggurat, and an associated temple.

Nimrud remained the capital of the Assyrian Empire during the reigns of Shamshi-Adad V (822–811 BC), Adad-nirari III (810–782 BC), Queen Semiramis (810–806 BC), Adad-nirari III (806–782 BC), Shalmaneser IV (782–773 BC), Ashur-dan III (772–755 BC), Ashur-nirari V (754–746 BC), Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (726–723 BC). Tiglath-Pileser III in particular, conducted major building works in the city, as well as introducing Eastern Aramaic as the lingua franca of the empire, whose dialects still endure among the Christian Assyrians of the region today.

However, in 706 BC Sargon II (722–705 BC) moved the capital of the empire to Dur Sharrukin, and after his death, Sennacherib (705–681 BC) moved it to Nineveh. It remained a major city and a royal residence until the city was largely destroyed during the fall of the Assyrian Empire at the hands of an alliance of former subject peoples, including the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians, and Cimmerians (between 616 BC and 599 BC).

Later geographical writings

[edit]Ruins of a similarly located Assyrian city named "Larissa" were described by Xenophon in his Anabasis in the 5th century BC.[17]

A similar locality was described in the Middle Ages by a number of Arabic geographers including Yaqut al-Hamawi, Abu'l-Fida and Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi, using the name "Athur" (meaning Assyria) near Selamiyah.[note 3]

Archaeology

[edit]Early writings and debate over name

[edit]Nimrud

[edit]The name Nimrud in connection with the site in Western writings was first used in the travelogue of Carsten Niebuhr, who was in Mosul in March 1760. Niebuhr [3] [note 1]

In 1830, traveller James Silk Buckingham wrote of "two heaps called Nimrod-Tuppé and Shah-Tuppé... The Nimrod-Tuppé has a tradition attached to it, of a palace having been built there by Nimrod".[18][19]

However, the name became the cause of significant debate amongst Assyriologists in the mid-nineteenth century, with much of the discussion focusing on the identification of four Biblical cities mentioned in Genesis 10: "From that land he went to Assyria, where he built Nineveh, the city Rehoboth-Ir, Calah and Resen".[20]

Larissa / Resen

[edit]The site was described in more detail by the British traveler Claudius James Rich in 1820, shortly before his death.[1] Rich identified the site with the city of Larissa in Xenophon, and noted that the locals "generally believe this to have been Nimrod's own city; and one or two of the better informed with whom I conversed at Mousul said it was Al Athur or Ashur, from which the whole country was denominated."[note 4]

The site of Nimrud was visited by William Francis Ainsworth in 1837.[1] Ainsworth, like Rich, identified the site with Larissa (Λάρισσα) of Xenophon's Anabasis, concluding that Nimrud was the Biblical Resen on the basis of Bochart's identification of Larissa with Resen on etymological grounds.[note 2]

Rehoboth

[edit]The site was subsequently visited by James Phillips Fletcher in 1843. Fletcher instead identified the site with Rehoboth on the basis that the city of Birtha described by Ptolemy and Ammianus Marcellinus has the same etymological meaning as Rehoboth in Hebrew.[note 5]

Ashur

[edit]Sir Henry Rawlinson mentioned that the Arabic geographers referred to it as Athur. British traveler Claudius James Rich mentions, "one or two of the better informed with whom I conversed at Mosul said it was Al Athur or Ashur, from which the whole country was denominated."[note 4]

Nineveh

[edit]Prior to 1850, Layard believed that the site of "Nimroud" was part of the wider region of "Nineveh" (the debate as to which excavation site represented the city of Nineveh had yet to be resolved), which also included the two mounds today identified as Nineveh-proper, and his excavation publications were thus labeled.[note 6]

Calah

[edit]Henry Rawlinson identified the city with the Biblical Calah[21] on the basis of a cuneiform reading of "Levekh" which he connected to the city following Ainsworth and Rich's connection of Xenophon's Larissa to the site.[note 2]

Excavations

[edit]

Initial excavations at Nimrud were conducted by Austen Henry Layard, working from 1845 to 1847 and from 1849 until 1851.[22] Following Layard's departure, the work was handed over to Hormuzd Rassam in 1853-54 and then William Loftus in 1854–55.[23][24]

After George Smith briefly worked the site in 1873 and Rassam returned there from 1877 to 1879, Nimrud was left untouched for almost 60 years.[25]

A British School of Archaeology in Iraq team led by Max Mallowan resumed digging at Nimrud in 1949; these excavations resulted in the discovery of the 244 Nimrud Letters. The work continued until 1963 with David Oates becoming director in 1958 followed by Julian Orchard in 1963.[26][27][28][29][30]

Subsequent work was by the Directorate of Antiquities of the Republic of Iraq (1956, 1959–60, 1969–78 and 1982–92),[31] the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw directed by Janusz Meuszyński (1974–76),[32] Paolo Fiorina (1987–89) with the Centro Ricerche Archeologiche e Scavi di Torino who concentrated mainly on Fort Shalmaneser, and John Curtis (1989).[31] In 1974 to his untimely death in 1976 Janusz Meuszyński, the director of the Polish project, with the permission of the Iraqi excavation team, had the whole site documented on film—in slide film and black-and-white print film. Every relief that remained in situ, as well as the fallen, broken pieces that were distributed in the rooms across the site were photographed. Meuszyński also arranged with the architect of his project, Richard P. Sobolewski, to survey the site and record it in plan and in elevation.[33] As a result, the entire relief compositions were reconstructed, taking into account the presumed location of the fragments that were scattered around the world.[32]

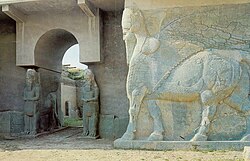

Excavations revealed remarkable bas-reliefs, ivories, and sculptures. A statue of Ashurnasirpal II was found in an excellent state of preservation, as were colossal winged man-headed lions weighing 10 short tons (9.1 t) to 30 short tons (27 t)[34] each guarding the palace entrance. The large number of inscriptions dealing with king Ashurnasirpal II provide more details about him and his reign than are known for any other ruler of this epoch. The palaces of Ashurnasirpal II, Shalmaneser III, and Tiglath-Pileser III have been located. Portions of the site have been also been identified as temples to Ninurta and Enlil, a building assigned to Nabu, the god of writing and the arts, and as extensive fortifications.

In 1988, the Iraqi Department of Antiquities discovered four queens' tombs at the site.

Artworks

[edit]

Nimrud has been one of the main sources of Assyrian sculpture, including the famous palace reliefs. Layard discovered more than half a dozen pairs of colossal guardian figures guarding palace entrances and doorways. These are lamassu, statues with a male human head, the body of a lion or bull, and wings. They have heads carved in the round, but the body at the side is in relief.[35] They weigh up to 27 tonnes (30 short tons). In 1847 Layard brought two of the colossi weighing 9 tonnes (10 short tons) each including one lion and one bull to London. After 18 months and several near disasters he succeeded in bringing them to the British Museum. This involved loading them onto a wheeled cart. They were lowered with a complex system of pulleys and levers operated by dozens of men. The cart was towed by 300 men. He initially tried to hook up the cart to a team of buffalo and have them haul it. However the buffalo refused to move. Then they were loaded onto a barge which required 600 goatskins and sheepskins to keep it afloat. After arriving in London a ramp was built to haul them up the steps and into the museum on rollers.

Additional 27-tonne (30-short-ton) colossi were transported to Paris from Khorsabad by Paul Emile Botta in 1853. In 1928 Edward Chiera also transported a 36-tonne (40-short-ton) colossus from Khorsabad to Chicago.[34][36] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has another pair.[37]

The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II, Stela of Shamshi-Adad V and Stela of Ashurnasirpal II are large sculptures with portraits of these monarchs, all secured for the British Museum by Layard and the British archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam. Also in the British Museum is the famous Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, discovered by Layard in 1846. This stands six-and-a-half-feet tall and commemorates with inscriptions and 24 relief panels the king's victorious campaigns of 859–824 BC. It is shaped like a temple tower at the top, ending in three steps.[38]

Series of the distinctive Assyrian shallow reliefs were removed from the palaces and sections are now found in several museums (see gallery below), in particular the British Museum. These show scenes of hunting, warfare, ritual and processions.[39] The Nimrud Ivories are a large group of ivory carvings, probably mostly originally decorating furniture and other objects, that had been brought to Nimrud from several parts of the ancient Near East, and were in a palace storeroom and other locations. These are mainly in the British Museum and the National Museum of Iraq, as well as other museums.[40] Another storeroom held the Nimrud Bowls, about 120 large bronze bowls or plates, also imported.[41]

The "Treasure of Nimrud" unearthed in these excavations is a collection of 613 pieces of gold jewelry and precious stones. It has survived the confusions and looting after the invasion of Iraq in 2003 in a bank vault, where it had been put away for 12 years and was "rediscovered" on June 5, 2003.[42]

Significant inscriptions

[edit]One panel of the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III has an inscription which includes the name mIa-ú-a mar mHu-um-ri-i While Rawlinson originally translated this in 1850 as "Yahua, son of Hubiri", a year later Reverend Edward Hincks, suggested that it refers to King Jehu of Israel (2 Kings 9:2 ff. While other interpretations exist, the obelisk is widely viewed by biblical archaeologists as therefore including the earliest known dedication of an Israelite. Note: all the kings of Israel were called "sons of Omri" by the Assyrians ("mar" means "son").

A number of other artifacts considered important to Biblical history were excavated from the site, such as the Nimrud Tablet K.3751 and the Nimrud Slab. The bilingual Assyrian lion weights were important to scholarly deduction of the history of the alphabet.

Destruction

[edit]Nimrud's various monuments had faced threats from exposure to the harsh elements of the Iraqi climate. Lack of proper protective roofing meant that the ancient reliefs at the site were susceptible to erosion from wind-blown sand and strong seasonal rains.[44]

In mid-2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) occupied the area surrounding Nimrud. ISIL destroyed other holy sites, including the Mosque of the Prophet Jonah in Mosul. In early 2015, they announced their intention to destroy many ancient artifacts, which they deemed idolatrous or otherwise un-Islamic; they subsequently destroyed thousands of books and manuscripts in Mosul's libraries.[45] In February 2015, ISIL destroyed Akkadian monuments in the Mosul Museum, and on March 5, 2015, Iraq announced that ISIL militants had bulldozed Nimrud and its archaeological site on the basis that they were blasphemous.[46][47][48]

A member of ISIL filmed the destruction, declaring, "These ruins that are behind me, they are idols and statues that people in the past used to worship instead of Allah. The Prophet Muhammad took down idols with his bare hands when he went into Mecca. We were ordered by our prophet to take down idols and destroy them, and the companions of the prophet did this after this time, when they conquered countries."[49] ISIL declared an intention to destroy the restored city gates in Nineveh.[47] ISIL went on to do demolition work at the later Parthian ruined city of Hatra.[50][51] On April 12 2015, an online militant video purportedly showed ISIL militants hammering, bulldozing, and ultimately using explosives to blow up parts of Nimrud.[52][53]

Irina Bokova, the director general of UNESCO, stated "deliberate destruction of cultural heritage constitutes a war crime".[54] The president of the Syriac League in Lebanon compared the losses at the site to the destruction of culture by the Mongol Empire.[55] In November 2016, aerial photographs showed the systematic leveling of the Ziggurat by heavy machines.[56] On 13 November 2016, the Iraqi Army recaptured the city from ISIL. The Joint Operations Command stated that it had raised the Iraqi flag above its buildings and also captured the Assyrian village of Numaniya, on the edge of the town.[57] By the time Nimrud was retaken, around 90% of the excavated part of the city had been destroyed entirely. Every major structure had been damaged, the Ziggurat of Nimrud had been flattened, only a few scattered broken walls remained of the palace of Ashurnasirpal II, the Lamassu that once guarded its gates had been smashed and scattered across the landscape.

Reconstruction of the site

[edit]A renovation program started in July 2017 with the support of UNESCO. The first phase included conducting studies of the damage caused to the site, assembling an Iraqi maintenance and rehabilitation team, preservation and archiving of the city's cultural heritage in co-operation with the American Smithsonian Institution. Phase 2 was launched in October 2019 with the goal to restore the northern palace.[58]

As of 2020, archaeologists from the Nimrud Rescue Project have carried out two seasons of work at the site, training native Iraqi archaeologists on protecting heritage and helping preserve the remains. Plans for reconstruction and tourism are in the works but will likely not be implemented within the next decade.[59] The first major excavation works, launched in mid-October 2022 by an excavation team from the University of Pennsylvania, reported the discovery of a door sill slab with inscriptions in December.[60]

Security post Islamic State

[edit]Following the liberation from Islamic State, the security of the ancient city is run by the ethnic Assyrian security force Nineveh Plain Protection Units.[61]

Gallery

[edit]- Items excavated from Nimrud, located in museums around the world

-

Nimrud ivory plaque, with original gold leaf and paint, depicting a lion killing a human (British Museum)

-

Assyrian lion hunt (Pergamon)

-

Lamassu, Stelas, Statue, Relief Panels, including the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (British Museum)

-

City under siege (British Museum)

-

Cavalry battle (British Museum)

-

Eagle-headed deity (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

-

Relief with Winged Genius (Walters Art Museum)

-

Two Nimrud ivories made in Egypt (British Museum)

-

Stela of Shamshi-Adad V, Height 195.2 cm, Width 92.5 cm, (British Museum)

-

Two archers (Hermitage Museum)

-

A human-headed and winged apkallu holding a pine cone and bucket for religious rituals (Museum of the Ancient Orient)

-

The first publication of a Phoenician metal bowl, one of 16 metal bowls from Nimrud with a Phoenician inscription (see letters on top sketch of the side profile)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Niebuhr wrote on p.355: [in original German]: "Bei Nimrud, einem verfallenen Castell etwa 8 Stunden von Mosul, findet man ein merkwürdigeres Werk. Hier ist von beiden Ufern ein Damm in den Tiger gebaut, um so viel Wasser zurück zu halten, als nöthig ist, die benachbarten Ländereien zu wässern." / [translated]: At Nimrud, a dilapidated castle about 8 hours outside of Mosul, one finds a more remarkable work. Here are both banks of a dam built in the Tigris to hold back as much water as is necessary to water the neighbouring lands."

- ^ a b c William Francis Ainsworth, who preferred the identification of Resen with Nimrud (on the basis of Bochart's identification of Resen with Xenophon's Larissa), summarised the debate in 1855 as follows: "The learned Bochart first advanced the supposition that this Assyrian city was the same as the primeval city, called Resen in the Bible and that the Greeks having asked its name were answered, Al Resen, the article being prefixed, and from whence they made Larissa, in an easy transposition. I adopted this presumed identity as extremely probable, and Colonel Chesney (ii. 223) has done the same, not as an established fact, but as a presumed identity. ... In 1846, Colonel Rawlinson, speaking of Nimrud, noticed it as probably the Rehoboth of Scripture, but he added in a note, 'I have no reason for identifying it with Rehoboth, beyond its evident antiquity, and the attribution of Resen and Calah to other sites.' (Journal of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. x. p. 26.) At this time Colonel Rawlinson identified Calah with Holwan or Sir Pul-i-Zohab, and Resen, or Dasen, with Yasin Teppeh in the plain of Sharizur in Kurdistan. In 1849 (Journ. of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. xi. p. 10), Colonel Rawlinson said, 'The Arabic geographers always give the title of Athur to the great ruined capital near the mouth of the Upper Zab. The ruins are now usually known by the name of Nimrud. It would seem highly probable that they represent the Calah of Genesis, for the Samaritan Pentateuch names this city Lachisa, which is evidently the same title as the Λάρισσα of Xenophon, the Persian r being very usually replaced both in Median and Babylonian by a guttural.' In 1850 (Journ. of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. xii.). Colonel Rawlinson added the discovery of a cuneiform inscription bearing the title Levekh, which he reads Halukh. 'Nimrud', says the distinguished palaeographist, 'the great treasure-house which has furnished us with all the most remarkable specimens of Assyrian sculpture, although very probably forming one of that group of cities, which in the time of the prophet Jonas, were known by the common name of Nineveh, has no claim, itself, I think, to that particular appellation. The title by which it is designated on the bricks and slabs that form its buildings, I read doubtfully as Levekh, and I suspect this to be the original form of the name which appears as Calah in Genesis, and Halah in Kings and Chronicles, and which indeed, as the capital of Calachene, must needs have occupied some site in the Immediate vicinity.' Lastly, in 1853 (Journ. of Roy. Asiat. Soc. vol. xv. p. vi. et seq.), Colonel Rawlinson describes the remarkable cylinder before alluded to as found at Kilah Shirgat, which establishes that site to have been the most ancient capital of the Assyrian empire, and to have been called Assur as well as Nimrud and Nineveh Proper. This Assur, we have seen, he identifies with the Tel Assur of the Targums, which is used for the Mosaic Resen; and instead, therefore, of Resen being between Nineveh and Calah, It should be Calah, which was between Nineveh and Resen. But, notwithstanding such very high authority, the conclusion thus arrived at does not appear to be perfectly satisfactory."

- ^ Layard (1849, p.194) noted the following in a footnote: "Yakut, in his geographical work called the Moejem el Buldan, says, under the head of "Athur," "Mosul, before it received its present name, was called Athur, or sometimes Akur, with a kaf. It is said that this was anciently the name of el Jezireh (Mesopotamia), the province being so called from a city, of which the ruins are now to be seen near the gate of Selamiyah, a small town, about eight farsakhs east of Mosul; God, however, knows the truth." The same notice of the ruined city of Athur, or Akur, occurs under the head of "Selamiyah." Abulfeda says, " To the south of Mosul, the lesser (?) Zab flows into the Tigris, near the ruined city of Athur." In Reinaud's edition (vol. i. p. 289, note 11,) there is the following extract from Ibn Said: — " The city of Athur, which is in ruins, is mentioned in the Taurat (Old Testament). There dwelt the Assyrian kings who destroyed Jerusalem.""

- ^ a b Rich (1836, p.129) described his interpretation as follows: "I was curious to inspect the ruins of Nimrod, which I take to be the Larissa of Xenophon. They were sufficiently visible from the shore to enable me to sketch the principal mount. About a quarter of a mile [400 m] from the west face of the platform is the large village of Nimrod, sometimes called Deraweish. The Turks generally believe this to have been Nimrod's own city; and one or two of the better informed with whom I conversed at Mousul said it was Al Athur or Ashur, from which the whole country was denominated. It is curious that the villagers of Deraweish still consider Nimrod as their founder. The village story-tellers have a book they call the "Kisseh Nimrod," or Tales of Nimrod, with which they entertain the peasants on a winter night. [Footnote: In the name of this obscure place seems to be preserved that of the first settler of the country, and from this spot, perhaps, that name extended over the whole vast region. See Gen. x. 11 . "Out of that land went forth Ashur and builded Nineveh," &c.; or, as it has been rendered, "Out of that land he went forth into Ashur,"i.e. Assyria. The former translation seems the preferable one; and the position of this village is avourable to the supposition of its having received very early a name afterwards to become so celebrated.]"

- ^ Fletcher (1850, p.75-78) described his thesis as follows: "The Tell of Nimroud and its lately discovered treasures have excited so much interest that I trust I may be pardoned if I interrupt the course of the narrative to bestow a few remarks on the identity of this site with that of the ancient city of Rehoboth, mentioned in Genesis x. 11. It is evident from the sculptures which have been discovered at Nimroud, that these mounds were in ancient days occupied by some large Assyrian city. Major Rawlinson, in his interesting paper on Assyrian Antiquities, quoted in the Athenceum of January 26, 1850, assumes that the ruins of Nimroud represent the old city of Calah, or Halah, while he places Nineveh at Nebbi Yunas. Yet it appears likely that the ancient Calah, or Halah, which was probably the capital of the district of Calachene, must have been nearer to the Kurdish Mountains. Ptolemy mentions the province of Calachene as bounded on the north by the Mountains of Armenia, and on the south by the district of Adiabene. [Ptolemy, lib. vi. cap. i.] Most writers place Ninus, or Nineveh, within the latter province. But if so, Adiabene would include also Nimroud, and, therefore, it is not probable that Halah, or Calah, could have occupied the site indicated by Major Rawlinson. St. Ephraim, himself a learned Syrian and well acquainted with the history and geography of the East, considers Calah to be the modern Hatareh, a large town inhabited chiefly by Yezidees, and situated N.N.W. of Nineveh. [Strabo, lib. 1G, mentions the plain in the vicinity of Nineveh, and seems to consider it as not belonging to the province of Adiabene. But his testimony, if taken, would also exclude that city, and the land to the southward of it, from the district of Calachene, as he enumerates that as a distinct part of Assyria immediately afterwards. In the arrangement of the dioceses recorded in Assemani, torn. iii. Athoor and Adiabene seem to be continually connected, while Calachene is spoken of as nearer the mountains.] Between Hatareh and the site of Nineveh we find a village bearing the name of Ras el Ain, which is evidently a corrupted form of the Resen of Genesis. It is worthy of remark that this theory confirms the statement made in Genesis x. 12, where Resen is represented as occupying a midway position between Calah and Nineveh. But assuming Major Rawlinson's hypothesis to be correct, it is clear that there would be no room for a large city between Nebbi Yunas and Nimroud, a distance of, at most, 40 kilometres (25 mi). Nor is it certain that the latter may be considered as the site of the Larissa of Xenophon. A considerable interval must have taken place between the passage of the river Zab by the Ten Thousand and their arrival at the Tigris. It is expressly mentioned that they forded a mountain stream, which seems to have been of some width, soon after they had passed over the Zab. But no vestige of any stream of this kind appears between Nimroud and the Tigris. It is probable, therefore, that the Χαραδρα of Xenophon was the Hazir, or Bumadas, after passing which, the Ten Thousand marched in a north-westerly direction past the modern village of Kermalis to the Tigris. At a short distance from the latter they encountered a ruined city, which Xenophon terms Larissa, and which occupied probably the site of the modern Ras el Ain. The village known by this name is about 19 kilometres (12 mi) from the Tigris, but the ancient city may have been much nearer. [Xenophon Anab. lib. iii. cap. iv.] Both Ptolemy and Ammianus Marcellinus mention a city situated at the mouth of the Zab, on precisely the same site as that occupied by the mounds of Nimroud, which they term Birtha, or Virtha. But Birtha, or Britha, in Chaldee, signifies the same as Rehoboth in Hebrew, namely, wide squares or streets, an identity in name which seems to imply also an identity in locality. It appears likely, therefore, that Nimroud is the same as Rehoboth, which it is said Asshur founded after his departure from the land of Shinar."

- ^ Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, "That the ruins at Nimroud were within the precincts of Nineveh, if they do not alone mark its site, appears to be proved by Strabo, and by Ptolemy's statement that the city was on the Lycus, corroborated by the tradition preserved by the earliest Arab geographers. Yakut, and others mention the ruins of Athur, near Selamiyah, which gave the name of Assyria to the province; and Ibn Said expressly states, that they were those of the city of the Assyrian kings who destroyed Jerusalem. They are still called, as it has been shown, both Athur and Nimroud. The evidence afforded by the examination of all the known ruins of Assyria, further identifies Nimroud with Nineveh. It would appear from existing monuments, that the city was originally founded on the site now occupied by these mounds. From its immediate vicinity to the place of junction of two large rivers, the Tigris and the Zab, no better position could have been chosen."

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Brill's Encyclopedia of Islam 1913-36, p.923

- ^ Mieroop, Marc van de (1997). The Ancient Mesopotamian City. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780191588457.

- ^ a b Brill's Encyclopedia of Islam 1913-36, p.923, "Nimrud": "At the present day the site is known only as Nimrud, which so far as I know first appears in Niebuhr (1778, p. 355, 368). When this, now the usual, name arose is unknown; I consider it to be of modern origin ... names like Nimrod, Tell Nimrod, etc. are not found in the geographical nomenclature of Mesopotamia and the Iraq in the Middle Ages, while they are several times met with at the present day."

- ^ The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org

- ^ The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org: Museums worldwide holding material from Nimrud; "Material from Nimrud has been dispersed into museum collections across the world. This page currently lists 76 museums holding Nimrud objects, with links to online information where available. The Nimrud Project welcomes additions and amendments to the list".

- ^ "Isis destroyed a 3,000-year-old city in minutes". The Independent. 2017-01-06. Archived from the original on 2022-06-21. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ^ Budge, Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis (1920). "By Nile and Tigris: a narrative of journeys in Egypt and Mesopotamia on behalf of the British Museum between the years 1886 and 1913". John Murray: London. OCLC 558957855.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2014) https://www.worldhistory.org/Kalhu/

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2014) https://www.worldhistory.org/Kalhu/

- ^ a b c d Mark 2020.

- ^ a b c d Frahm 2017, p. 170.

- ^ Frahm, Eckhart (2017). "The Neo-Assyrian Period (ca.1000-609 BCE)", in A Companion to Assyria. John Wiley and Sons. p. 170.

- ^ "The 19 greatest cities in history". Business Insider.

- ^ "Largest Ancient Cities". artoftravel.tips/. 800 BC: Nimrud (Calah), Iraq: Haojing, China: Thebes, Egypt: Estimated population: 50,000 – 125,000

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2014) https://www.worldhistory.org/Kalhu/

- ^ Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Mesopotamia: The Mighty Kings. (1995) p. 100–1

- ^ Xen. Anab. 3.4.7. The city had been reached after crossing the "Zapatas" river (Xen. Anab. 3.3.6) and then arriving at the Tigris ([Citation URI: http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0032.tlg006.perseus-eng1:3.4.6 Xen. Anab. 3.4.6]).

- ^ Buckingham, James Silk (1830). Travels in Assyria, Media, and Persia, Including a Journey from Bagdad by Mount Zagros, to Hamadan, the Ancient Ecbatani, Researches in Ispahan and the Ruins of Persepolis, and Journey from Thence by Shiraz and Shapoor to the Sea-shore; Description of Bussorah, Bushire, Bahrein, Ormuz and Museat: Narrative of an Expedition Against the Pirates of the Persian Gulf, with Illustrations of the Voyage of Nearehus, and Passage by the Arabian Sea to Bombay. H. Colburn. p. 54.

Our course now lay nearly east, over a plain, which brought us in half an hour to the two heaps called Nimrod-Tuppé and Shah-Tuppé, between which we passed, without seeing any thing remarkable in them, more than common mounds of earth; though they probably might have shown vestiges of former buildings had they been carefully examined, a task which I could not now step aside from the road to execute. The Nimrod-Tuppé has a tradition attached to it, of a palace having been built there by Nimrod; and the Shah-Tuppé is said by some to have been a pleasure-house; by others, to be the grave of an Eastern monarch, coming on a pilgrimage to Mecca from India, who, being pleased with the beauty of the situation, halted here to take up his abode, and ended his days on the spot.

- ^ "Julius Weber (1838–1906) and the Swiss Excavations at Nimrud in c.1860 together with Records of. Other Nineteenth-Century Antiquarian Researches at the Site" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- ^ Genesis 10:11–10:12

- ^ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 12, page 417, quote "The title by which it is designated on the bricks and slabs that form its buildings, I read doubtfully as Levekh, and I suspect this to be the original form of the name which appears as Calah in Genesis, and Halah in Kings and Chronicles..."

- ^ Layard, 1849

- ^ Hormuzd Rassam and Robert William Rogers, Asshur and the land of Nimrod, Curts & Jennings, 1897

- ^ The Conquest of Assyria, Mogens Trolle Larsen, 2014, Routledge, page 217, quote: "Rawlinson explained to his audience that the large Assyrian ruin mounds could now be given their proper names: Nimrud was Calah..."

- ^ George Smith, Assyrian Discoveries: An Account of Explorations and Discoveries on the Site of Nineveh During 1873 to 1874, Schribner, 1875

- ^ M. E. L. Mallowan, "The Excavations at Nimrud. 1949 Season", Sumer, vol. 6, no.1, pp. 101-102, 1950

- ^ M. E. L. Mallowan, "The Excavations at Nimrud (Kahlu), 1950", Sumer, vol. 7, no.1, pp. 49-54, 1951

- ^ M. E. L. Mallowan, Nimrud and its Remains, 3 vols, British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1966

- ^ Joan Oates and David Oates, Nimrud: An Imperial City Revealed, British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2001, ISBN 0-903472-25-2

- ^ D. Oates and J. H. Reid, The Burnt Palace and the Nabu Temple; Nimrud Excavations, 1955, Iraq, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 22-39, 1956

- ^ a b Paolo Fiorina, Un braciere da Forte Salmanassar, Mesopotamia, vol. 33, pp. 167–188, 1998

- ^ a b "Nimrud". pcma.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2020-07-08.

- ^ Janusz Meuszynski, Neo-Assyrian Reliefs from the Central Area of Nimrud Citadel, Iraq, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 37-43, 1976

- ^ a b Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Mesopotamia: The Mighty Kings. (1995) p. 112–121

- ^ Frankfort, 154

- ^ Oliphant, Margaret The Atlas Of The Ancient World (1992) p. 32

- ^ Human–headed winged lion (lamassu), 883–859 b.c.; Neo–Assyrian period, reign of Ashurnasirpal II

- ^ Frankfort, 156-157, 167

- ^ "Assyria: Nimrud (Rooms 7–8)", British Museum, accessed 6 March 2015;Frankfort, 156-164

- ^ Frankfort, 310-322

- ^ The Nimrud Bowls, British Museum, accessed 6 March 2015; Frankfort, 322-331

- ^ "Ancient Assyrian Treasures Found Intact in Baghdad". National Geographic. Archived from the original on October 8, 2003. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Iraq's Nimrud before it was destroyed by Isis | Guardian Wires". YouTube. 6 March 2015.

- ^ Jane Arraf (February 11, 2009). "Iraq: No Haven for Ancient World's Landmarks". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "Isis destroys thousands of books and manuscripts in Mosul libraries". The Guardian. 26 Feb 2015.

- ^ Karim Abou Merhi (March 5, 2015). "IS 'bulldozed' ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, Iraq says". AFP. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Iraq: Isis militants pledge to destroy remaining archaeological treasures in Nimrud". The Independent. 27 Feb 2015. Archived from the original on 2022-06-21.

- ^ Al Jazeera: ISIL video shows destruction of 7th century artifacts (26 February 2015)

- ^ Morgan Winsor (5 March 2015). "ISIS Destroys Iraqi Archaeological Site Of Nimrud Near Mosul". IBT. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Isis militants continue path of destruction in Hatra by 'demolishing 2,000 year-old ruins'". The Independent. 7 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2022-06-21.

- ^ "Islamic State 'demolishes' ancient Hatra site in Iraq". BBC. 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Islamic State video 'shows destruction of Nimrud'". BBC. 7 March 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ youtube ISIS destroys Nimrud

- ^ "Isis 'bulldozes' Nimrud: UNESCO condemns destruction of ancient Assyrian site as a 'war crime'". The Independent. 6 Mar 2015. Archived from the original on 2022-06-21.

- ^ Kareem Shaheen (7 March 2015). "Outcry over Isis destruction of ancient Assyrian site of Nimrud". The Guardian.

- ^ "Iconic Ancient Sites Ravaged in ISIS's Last Stand in Iraq. National geographic 10 november 2016". Archived from the original on November 11, 2016.

- ^ Williams, Sara Elizabeth (13 November 2016). "Iraqi forces retake historical town of Nimrud". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ al-Taie, Khalid. "Iraq begins phase 2 of Nimrud ancient city reconstruction". Diyaruna. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ^ Johnson, Jessica S.; Ghazi, Zaid; Hanson, Katharyn; Lione, Brian Michael; Severson, Kent (2020-08-31). "The Nimrud Rescue Project". Studies in Conservation. 65 (sup1): P160 – P165. doi:10.1080/00393630.2020.1753357. ISSN 0039-3630. S2CID 219037067.

- ^ "First major dig in ancient Iraqi city since Isis destruction unearths 'significant' palace door sill". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. 2022-12-07. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ^ Contested Control: The Future of Security in Iraq's Nineveh Plain

General references

[edit]- Frankfort, Henri, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, Pelican History of Art, 4th ed 1970, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561072

- A. H. Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, John Murray, 1849 (Vol. 1 and Vol. 2)

Further reading

[edit]- Crawford, Vaughn E.; et al. (1980). Assyrian reliefs and ivories in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: palace reliefs of Assurnasirpal II and ivory carvings from Nimrud. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870992605.

- Russell, John Malcolm (1998). "The Program of the Palace of Assurnasirpal II at Nimrud: Issues in the Research and Presentation of Assyrian Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 102 (4): 655–715. doi:10.2307/506096. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 506096. S2CID 191618390.

- Barbara Parker, Seals and Seal Impressions from the Nimrud Excavations, Iraq, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 26–40 1962

- Barbara Parker, "Nimrud Tablets, 1956: Economic and Legal Texts from the Nabu Temple", Iraq, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 125–138, 1957

- D. J. Wiseman, "The Nabu Temple Texts from Nimrud", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 248–250, 1968

- D. J. Wiseman, Fragments of Historical Texts from Nimrud, Iraq, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 118–124, 1964

- A. H. Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, John Murray, 1853

- A. H. Layard, The monuments of Nineveh; from drawings made on the spot, John Murray, 1849

- Claudius James Rich, Narrative of a residence in Koordistan, and on the site of ancient Nineveh. Ed. by his widow, 1836

- James Phillips Fletcher, Narrative of a Two Years' Residence at Nineveh, Volume 2, 1850

- Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs. 2016

External links

[edit]- Metropolitan Museum: Digital Reconstruction of the Northwest Palace, Nimrud, Assyria

- Nimrud/Calah

- Kalhu / Nimrud

- Centro Ricerche Archeologiche e Scavi di Torino excavation site

- Archaeological site photographs at Oriental Institute

- More images from National Geographic

- "Treasure of Nimrud rediscovered", article from The Wall Street Journal posted to a message board

- The Secret of Nimrud - Photographs by Noreen Feeney

Nimrud

View on GrokipediaIdentification and Etymology

Biblical and Classical Associations

In the Hebrew Bible, the city of Calah (כַּלַח) appears in Genesis 10:11–12 as one of four key settlements established in Assyria, listed alongside Nineveh, Rehoboth-Ir, and Resen: "From that land he went to Assyria, where he built Nineveh, Rehoboth Ir, Calah, and Resen, which is between Nineveh and Calah—which is the great city."[6] This passage attributes the founding to Nimrod, a descendant of Cush described as "a mighty warrior on the earth" and "a mighty hunter before the Lord" (Genesis 10:8–9), or in some interpretations to Asshur, emphasizing early Mesopotamian urban development extending from Shinar into Assyrian territories. Assyrian cuneiform records confirm the site's ancient name as Kalhu, directly equating it with the biblical Calah and underscoring its role as a foundational Assyrian center distinct from Nineveh to the north.[7] Classical Greek sources further associate the location with Larissa, a ruined Assyrian city noted for its monumental brick walls. Xenophon, in his Anabasis (3.4.7–11), describes the Ten Thousand passing such ruins in 401 BCE: a vast enclosure with walls 20 feet thick and 100 feet high, constructed from sun-dried and baked bricks set in bitumen, situated beside the Tigris amid otherwise unfortified plains.[8] This matches the archaeological profile of Nimrud's defenses, positioning it geographically separate from Nineveh's mounds approximately 30 kilometers north and Ashur further southwest along the river, as delineated in ancient Mesopotamian itineraries. Ptolemy's Geography (ca. 150 CE) and Strabo's accounts of Assyrian toponyms reinforce Larissa's placement in the region's core, aligning with Kalhu's historical prominence without conflation with neighboring urban centers.Modern Identification Debates

In the early 19th century, scholars grappled with identifying the biblical city of Calah (Hebrew Kaleḥ), mentioned in Genesis 10:11–12 as one of the Assyrian settlements founded by Nimrod alongside Nineveh, Rehoboth-Ir, and Resen, leading to speculation that Calah might coincide with Nineveh's expansive ruins or other Mesopotamian mounds like those at Ashur due to the text's ambiguous geography and the multiplicity of toponyms.[9] Local Arabic traditions had already dubbed several Assyrian ruin mounds "Nimrud" after the biblical hunter-king, but without epigraphic confirmation, European explorers and biblical archaeologists, including Claudius James Rich in his 1820 surveys, hesitated to pinpoint Calah's site amid broader uncertainties about Assyrian urban nomenclature.[4] Austen Henry Layard's excavations at the Nimrud mound from 1845 to 1847 shifted the debate decisively, as his team unearthed cuneiform inscriptions explicitly naming the city Kalḫu (Kalhu), the Assyrian form corresponding to biblical Calah, including royal annals from kings like Ashurnasirpal II who referenced its monuments and history.[4] [10] These findings, corroborated by Henry Rawlinson's parallel decipherment efforts on similar inscriptions, refuted earlier conflations with Nineveh (identified at the Kuyunjik mound) by demonstrating Kalhu's distinct identity as a secondary Assyrian capital founded centuries earlier.[10] By the 1850s, the consensus solidified through cross-referencing Layard's inscribed stelae and palace reliefs with Assyrian king lists, which traced Kalhu's origins to Shalmaneser I's reign around 1274–1245 BCE, though debates lingered briefly over minor toponymic variants like Rehoboth-Ir until further epigraphic evidence clarified their separation.[3] This resolution hinged on the inscriptions' internal consistency rather than solely biblical typology, establishing Nimrud as the archaeological type-site for Kalhu and underscoring the value of cuneiform over classical or scriptural sources alone in site identification.[10]Ancient History

Foundation and Early Settlement

Kalhu, the ancient Assyrian name for Nimrud, was established by King Shalmaneser I (r. c. 1274–1245 BC) during the Middle Assyrian period as a strategic settlement on the northeastern bank of the Tigris River, approximately 30 km southeast of modern Mosul and near the confluence with the Greater Zab. This foundation aligned with Assyrian military campaigns to consolidate control over northern Mesopotamia, countering threats from Hurrian principalities in the wake of Mitanni's collapse. Shalmaneser I's construction of the city is attested in later inscriptions by Ashurnasirpal II, who described it as having been built by his predecessor but left in ruins by the 9th century BC.[1][11] Archaeological evidence for the initial phase remains sparse, hampered by the substantial overlying Neo-Assyrian layers and limited deep excavations. Discoveries include mud-brick remnants, a Middle Assyrian tomb containing faience rosettes and a glass bead, seal impressions, and faience ornaments near the Kidmuru temple, indicating modest occupation predating monumental stone architecture. The site's advantageous position supported irrigation from the Greater Zab for agriculture, access to bitumen deposits for building, and oversight of regional trade and transport routes.[1] Administrative texts from the reign of Tiglath-pileser I (r. 1114–1076 BC) reference Kalhu as a provincial center, with a c. 1200 BC letter noting Kassite prisoners there, underscoring its early role in Assyrian governance amid fluctuating borders. However, the settlement did not develop into a major urban hub until its 9th-century BC reconstruction.[1]

Role as Neo-Assyrian Capital

Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC) shifted the Neo-Assyrian capital from the traditional religious center of Ashur to Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), designating it the empire's primary administrative and political hub around 879 BC.[12] [13] This relocation centralized governance and military operations, with the king constructing the Northwest Palace on the eastern citadel mound as a monumental complex adorned with reliefs depicting conquests and rituals to project imperial authority.[14] The palace incorporated innovative administrative spaces, including throne rooms and record-keeping areas, supporting the empire's expanding bureaucracy and resource management.[3] Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 BC), Ashurnasirpal's successor, undertook significant expansions at Nimrud to accommodate the demands of relentless warfare, erecting Fort Shalmaneser—a vast arsenal and storage facility along the city's southern perimeter spanning over 4 hectares.[15] This structure housed weapons, provisions, and chariots essential for Shalmaneser's 35 documented campaigns, which targeted western coalitions including Aram-Damascus and northern adversaries like Urartu, thereby extending Assyrian influence across the Near East.[16] Accompanying developments included temple dedications, such as those to Nabu, which reinforced the city's role in integrating divine sanction with military logistics. Nimrud's economic prominence stemmed from engineered irrigation networks, notably canals branching from the Tigris like the Nabu Canal, which irrigated thousands of hectares of arable land around the city and boosted grain production to feed imperial forces and urban populations.[17] [18] These hydraulic innovations, combined with tribute inflows from subjugated regions—encompassing metals, livestock, and luxury goods—fueled the empire's fiscal and logistical capacity during its mid-9th-century territorial zenith under these rulers.[19]Fall and Post-Assyrian Period

Nimrud's status as the Neo-Assyrian capital diminished after Sargon II relocated the royal court to Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad) in 706 BC, following the completion of his new palace complex there.[20] Although Dur-Sharrukin was abandoned shortly after Sargon's death in 705 BC, his successor Sennacherib shifted the administrative center to Nineveh, preventing Nimrud from regaining prominence as the empire's political hub.[20] This relocation reflected broader Assyrian challenges, including the logistical strains of maintaining an overextended empire across vast territories, which diverted resources and attention from earlier centers like Nimrud.[20] By the late 7th century BC, internal rebellions and external pressures compounded these issues, weakening Assyrian control over peripheral provinces and inviting coordinated assaults from rising powers. In 612 BC, a coalition comprising the Medes under Cyaxares, Babylonians led by Nabopolassar, and possibly Scythian allies sacked Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), systematically destroying palaces and temples amid widespread fires that left stratigraphic layers of ash and charred debris across the site.[20] [21] Archaeological excavations, including those revealing preserved shrines in the Ninurta Temple due to the incendiary destruction around 612–614 BC, confirm the violence's scale and the role of fire in entombing structures.[21] These events marked the effective end of Nimrud's role in Assyrian imperial administration, as the city's defenses and infrastructure were irreparably compromised by the attackers' tactics, which targeted monumental architecture to symbolize the empire's collapse. Following the Assyrian Empire's fall, Nimrud saw no significant revival, with the site largely abandoned and gradually accumulating as a tell through natural sedimentation and minor erosion over centuries. Sporadic, impoverished occupation persisted intermittently into the Hellenistic period, evidenced by a small village on the acropolis dated roughly 220–140 BC, yielding post-Assyrian pottery and structures indicative of limited, non-urban reuse.[22] Traces of activity may have extended into the Parthian era, though archaeological data remains inconclusive and suggests only transient or peripheral settlement without restoration of the city's former scale or function.[2] This post-imperial phase underscores Nimrud's transformation from a fortified capital into an archaeological mound, buried under layers that preserved but obscured its Assyrian legacy until modern rediscovery.[20]Archaeological Investigations

19th-Century Pioneering Excavations

Austen Henry Layard initiated excavations at Nimrud in 1845, targeting the mound known locally as Nimrud after the biblical figure.[23] Working intermittently until 1847 and resuming from 1849 to 1851, Layard uncovered portions of the Southwest Palace associated with Assurnasirpal II, along with ceremonial precincts and monumental sculptures including winged bulls.[23] [24] These discoveries, including palace reliefs and statues, were systematically transported to the British Museum, marking the first major revelation of Neo-Assyrian architecture's grandeur.[25] Assisted by Hormuzd Rassam, an Iraqi Christian scholar from Mosul, Layard's team employed basic tunneling and digging methods amid limited resources.[25] Rassam continued supplementary work in the early 1850s following Layard's departure, excavating additional palace areas and recovering fragments of carved ivories from debris layers.[23] These efforts supplemented Layard's findings but operated under rudimentary techniques that often failed to record stratigraphic contexts, prioritizing artifact extraction over site preservation.[26] Excavations faced persistent threats from local tomb-robbing, as villagers sporadically dug for saleable antiquities, complicating controlled recovery.[27] The era's pioneering approaches, reliant on manual labor and minimal documentation, yielded invaluable artifacts but sacrificed much provenience data essential for later interpretations.[23] Despite these limitations, the 19th-century digs established Nimrud's significance as a Neo-Assyrian capital through tangible evidence shipped to European institutions.[24]20th-Century Systematic Exploration

The British School of Archaeology in Iraq initiated systematic excavations at Nimrud from 1949 to 1963, directed initially by Max Mallowan and later by David Oates, shifting focus from 19th-century treasure-hunting to stratigraphic analysis of key structures like Fort Shalmaneser—a fortified arsenal and palace in the northwestern citadel—and associated temples such as those of Ishtar and Ninurta.[28][29] These efforts employed grid-based trenching and meticulous recording to establish chronological sequences, revealing multiple building phases from the 9th century BCE onward, including repairs under later Assyrian kings like Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.[30] Mallowan's campaigns, spanning nine seasons by 1958, yielded detailed architectural plans and clarified the site's defensive layouts, enhancing understanding of Neo-Assyrian urban fortification techniques.[31] Parallel Iraqi-led excavations by the State Organization of Antiquities and Heritage, commencing in 1956 on the high mound and continuing intermittently through 1960 and from 1969 to 1993, targeted the Ezida temple complex—dedicated to Nabu, the god of writing and wisdom—and peripheral suburbs.[32][33] These operations, under directors like Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, uncovered cuneiform tablets, ritual deposits, and domestic remains, providing stratigraphic evidence of continuous occupation and scribal activities from the Assyrian period into later eras.[34] The work at Ezida illuminated temple refurbishments and adjacent administrative buildings, contributing to a layered chronology that distinguished Assyrian foundations from Parthian and Islamic overlays.[31] By the late 20th century, combined British and Iraqi documentation had mapped extensive urban features, including the circuit of massive mud-brick city walls (up to 20 meters thick and 15 meters high), multi-arched aqueducts channeling water from distant springs, and sprawling residential quarters with multi-room houses and workshops.[35] These pre-2014 surveys and plans, derived from geophysical prospection and targeted digs, delineated Nimrud's 360-hectare footprint, revealing infrastructural sophistication like canal systems supporting agriculture and a population estimated at 50,000–100,000 in its Assyrian heyday.[23] Such systematic approaches contrasted with earlier haphazard methods, prioritizing contextual preservation over artifact extraction and forming the basis for subsequent heritage assessments.[36]Principal Architectural and Urban Features

The citadel of Nimrud occupied a prominent mound on the east bank of the Tigris River, serving as the core of the city's monumental architecture and encompassing royal palaces, temples, and a ziggurat within a fortified enclosure. The Northwest Palace, initiated by Ashurnasirpal II circa 879 BCE, exemplified Assyrian palatial design with its multi-courtyard layout, including throne halls, administrative wings, and private quarters arranged around open spaces for ceremonial and functional purposes.[14] Later additions, such as Fort Shalmaneser built by Shalmaneser III in the mid-9th century BCE, featured robust perimeter walls enclosing approximately 30 hectares and a central palace measuring about 200 by 300 meters, optimized for military storage and operations.[15] Religious structures dominated the southeastern citadel, highlighted by the ziggurat dedicated to Ninurta, the city's patron deity of war and agriculture, which anchored a sacred precinct with associated temples and rose as a stepped mud-brick pyramid in antiquity.[37] The Ezida temple complex, devoted to Nabu the god of writing and wisdom (alongside his consort Tashmetum), occupied a key position with twin shrines and ritual spaces, while additional temples honored deities including Ishtar, reflecting the polytheistic framework integrated into urban planning.[7] Encircling the urban expanse, Nimrud's city walls traced a perimeter of approximately 8 kilometers, constructed with mud-brick on stone foundations to enclose an area of about 360 hectares, incorporating towers and gates for defense.[38] Hydraulic engineering supported this layout through the Nimrud canal, a major diversion from the Tigris River that facilitated irrigation for surrounding fields, managed seasonal flooding, and potentially augmented defensive barriers via water channels.[39] Archaeological surveys indicate suburban residential quarters extending beyond the walled core, with dense housing and workshops evidencing urban growth and a peak population estimated between 50,000 and 100,000 during the 9th-7th centuries BCE, sustained by the canal system's agricultural enhancements.[2]Key Artifacts and Epigraphic Evidence

Monumental Sculptures and Reliefs

Monumental sculptures at Nimrud primarily consist of colossal lamassu figures and extensive wall relief panels adorning the palaces of Neo-Assyrian kings, particularly Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BCE). These works, carved in the round or in low relief, served propagandistic purposes by visually asserting royal power and divine protection through depictions of warfare, rituals, and supernatural guardians. Placed at palace thresholds and interior walls, they aimed to intimidate visitors and ward off malevolent forces via apotropaic symbolism.[40][41] Lamassu, hybrid creatures with human heads, bovine or leonine bodies, and eagle wings, flanked doorways in the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, embodying protective deities that neutralized evil influences. Often sculpted over ten feet tall from local gypsum alabaster—prized for its fine grain and carvability, dubbed "Mosul marble"—these statues incorporated five legs to appear four-legged in profile and two-legged frontally, enhancing their dynamic presence from multiple viewpoints. Winged genii, or apkallu, appeared in reliefs as bearded figures with bird or human features, performing rituals like tree fertilization to symbolize fertility and royal legitimacy, further exemplifying apotropaic functions in palace corridors.[40][3][42] Relief panels vividly portrayed Assyrian military campaigns, including sieges, impalements, and mass deportations, as seen in Ashurnasirpal II's throne room sequences showing captives herded after conquests. These unromanticized scenes of brutality—such as soldiers flaying enemies or reviewing bound prisoners—underscored the empire's ruthless expansion without idealization, functioning as historical propaganda to glorify the king's annals in visual form. Crafted from the same gypsum slabs, the reliefs lined public reception areas, their realism derived from detailed observation of combat and submission, influencing later Achaemenid palace art at Persepolis through shared motifs of procession and tribute.[43][44][13]Ivories and Craft Production

Excavations at Nimrud revealed over 6,000 ivory artifacts, many recovered from burnt caches in palaces such as the Northwest Palace and Fort Shalmaneser, where fires during the Median sack around 614 BC preserved fragments through charring.[45] These caches, including wells NN, AB, and AJ in the Northwest Palace yielding approximately 90 finely carved pieces in wicker baskets, and Room SW12 in Fort Shalmaneser with 430 items, demonstrate the scale of luxury furnishing for royal residences.[46] The ivories, often depicting mythological scenes, fauna like lions attacking Nubians, and Egyptian-inspired motifs such as pharaoh statuettes, reflect technical sophistication in openwork carving, inlays of shell and glass, and occasional gilding.[45][47] Evidence indicates on-site craft production and assembly under Assyrian royal patronage, with unworked ivory tusks and trial pieces found in Court AJ of the Northwest Palace, alongside tools like bone awls and spatulae in Well NN.[46] Maker's marks, including Aramaic or Phoenician letters on plaques, and variations in carving styles suggest multiple artisans, possibly foreign specialists from Phoenician centers like Tyre or Sidon, worked locally to customize furniture panels and pyxides.[46][47] Storage in dedicated rooms such as V, HH, SW7, SW11, and SW37 points to organized workshops integrating imported blanks with Assyrian motifs like "wig and wing" figures.[45] Trade networks supplied raw elephant ivory, likely from African sources via Levantine ports, as tribute or booty from Assyrian campaigns against Arpad, Damascus, and Carchemish, enabling the influx of Phoenician and North Syrian styles evident in over 50% of the corpus.[47][46] This cosmopolitan production highlights Nimrud's role as a hub for luxury goods, with ivories paralleling finds at sites like Samaria, Khorsabad, and Arslan Tash, underscoring extensive Mediterranean exchange from the 9th to 7th centuries BC.[45] Preservation challenges persist due to fire damage, waterlogging, and post-excavation looting, yet conservation efforts have revealed original paints and gold leaf on select pieces.[45]Inscriptions and Historical Records

The foundation inscriptions of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BCE), extensively attested in the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), comprise the Standard Inscription, a repetitive Akkadian cuneiform text inscribed on numerous wall slabs and architectural elements.[48] This text chronicles the king's conquests, resource mobilization for construction, and the palace's dedication to the god Ashur as a "joyful palace, the palace full of wisdom," emphasizing divine favor and royal prowess in transforming the site into a capital.[49] Accompanying annals detail brutal pacification of rebellions, including flaying rebel leaders and draping their skins over corpse piles as pillars of victory, which preceded the palace's inauguration banquet for 69,574 attendees, involving the ritual slaughter of 1,000 oxen, 14,000 sheep, and vast quantities of grain, wine, and beer to symbolize imperial abundance amid terror.[50] The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BCE), unearthed at Nimrud's Temple of Nabu, bears multi-register cuneiform inscriptions summarizing 31 years of campaigns, alliances, and tribute extractions across the Near East.[51] One panel records the 841 BCE submission of Jehu, identified as "son of Omri" and king of Israel, prostrating before the Assyrian king with offerings of silver, gold, a golden bowl, tin, and staffs of gold—marking the earliest extra-biblical depiction of an Israelite monarch and evidencing Assyrian dominance over western vassals.[52] These texts, alongside victory stelae, project Shalmaneser's role in stabilizing frontiers through repeated military expeditions and diplomatic pacts, such as with Tyre and Sidon. Subsequent royal annals from Nimrud, including those of Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BCE) and Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BCE), inscribed on clay prisms and cylinders, meticulously log annual campaigns with precise tallies of defeated foes (e.g., thousands slain or deported), cities sacked, and tribute amassed, reflecting the empire's bureaucratic precision in documentation and resource allocation.[53] For instance, Esarhaddon's cylinder from Nimrud's Fort Shalmaneser enumerates restorations of temples and palaces alongside conquests in Egypt and Anatolia, underscoring coordinated imperial administration via eponymous dating and archival records that facilitated governance over diverse provinces. Such epigraphic corpus, preserved in thousands of tablets, reveals Assyria's reliance on standardized reporting to enforce loyalty and extract revenues, though inherently propagandistic in glorifying monarchs while omitting defeats.[55]ISIS Destruction and Ideological Context

ISIS Seizure and Demolition Tactics

ISIS forces captured Nimrud in June 2014 amid their advance on Mosul, enabling initial access for looting operations targeting portable artifacts such as ivories, seals, and small sculptures, which were extracted and trafficked through black markets in Turkey, Lebanon, and Europe to generate revenue estimated in tens of millions of dollars annually for the group.[56][57] These activities preceded more overt structural demolitions, with looted items often funneled via intermediaries to auction houses and private collectors despite international bans.[58] On March 5, 2015, ISIS released a propaganda video documenting the use of bulldozers and excavators to systematically raze surface remains at major complexes, including the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II and surrounding fortifications, flattening walls and monumental gateways over several days.[59][60] Fighters also employed sledgehammers to smash exposed reliefs and statues before mechanical demolition, targeting visible Assyrian-era architecture to erase physical traces.[61] In the following weeks, ISIS escalated tactics by detonating explosives, including a truck-borne improvised explosive device at the site's ziggurat temple, which collapsed the mud-brick structure into rubble and scattered debris across the mound.[62] These blasts focused on residual standing elements like palace substructures and the Swy Bluff temple platform, pulverizing baked-brick foundations and gypsum plasters that had withstood millennia.[63] Satellite imagery from DigitalGlobe captured the pre-destruction state of the Northwest Palace in early 2015, contrasting sharply with post-March images revealing extensive trenching, leveled profiles, and rubble mounds, corroborating video evidence of targeted erasure.[64] Following Iraqi forces' liberation of the site on November 13, 2016, drone surveys documented the full extent of bulldozer tracks, blast craters, and scattered architectural fragments, confirming demolition efficacy without prior selective preservation.[65][66]Religious Motivations and Iconoclastic Ideology

The Islamic State (ISIS) justified its destruction of Nimrud and other pre-Islamic sites through a rigid interpretation of Islamic theology emphasizing tawhid (the oneness of God), which it claimed necessitated the eradication of artifacts perceived as promoting shirk (polytheism) or remnants of jahiliyyah (the pre-Islamic era of ignorance). Drawing from Salafi-jihadist traditions influenced by Wahhabi iconoclasm, ISIS viewed Assyrian monumental sculptures, such as lamassu figures and reliefs, as idolatrous representations akin to forbidden statues condemned in certain hadiths prohibiting images of living beings.[67][68] This stance echoed historical precedents like the Taliban's 2001 demolition of the Bamiyan Buddhas, where similar appeals to monotheistic purity were invoked to legitimize cultural annihilation.[69] In propaganda materials, including videos released following the March 5, 2015, demolition of Nimrud, ISIS framed the acts as a religious imperative to enforce tawhid by purging lands under its control of polytheistic symbols, declaring the site a "mushrik" (polytheist) location unfit for a caliphate.[70][61] Militants in related footage from the Mosul Museum—where Assyrian artifacts from Nimrud were stored—explicitly cited prophetic traditions against idols, smashing statues while invoking divine commands to destroy what they deemed false gods.[71] These narratives positioned iconoclasm not as mere vandalism but as a theological restoration of Islamic purity, prioritizing doctrinal absolutism over historical preservation.[72] This ideology extended beyond Assyrian heritage to a systematic rejection of non-conforming religious histories, targeting Yazidi temples and Christian monasteries as emblematic of pluralism antithetical to ISIS's vision of unadulterated Sunni orthodoxy.[67] By equating diverse pre-modern legacies with deviation from true monotheism, ISIS sought to causally sever cultural ties to alternative narratives, enforcing a monolithic religious identity that admitted no rivals.[70] Such motivations, rooted in selective literalism of Islamic sources, disregarded archaeological value in favor of an ahistorical purism that viewed survival of these sites as perpetuating error.[68]Damage Assessment and Looting Patterns

Post-liberation ground surveys conducted in November 2016 revealed extensive damage to Nimrud's monumental architecture, with an estimated 70% of the site's historical structures destroyed by ISIS through targeted use of explosives, sledgehammers, drills, and earth-moving equipment primarily between February and June 2015.[62] The Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, including its throne room gate and protective lamassu figures, was demolished with ammonium nitrate blasts and heavy machinery, reducing sculpted reliefs and gateways to pulverized rubble and scattered fragments.[73] Similarly, the Temple of Nabu saw its fish gate collapsed and walls partially exposed, while the ziggurat was later leveled in August-October 2016 using earthmovers, severely compromising stratigraphic layers across the site through blast-induced disturbance and mechanical excavation that scattered and mixed archaeological deposits.[74][73] Distinct from this systematic pulverization of visible idols and palaces—aimed at eradicating pre-Islamic heritage—opportunistic looting preceded the overt demolitions, with ISIS excavating for portable items such as figurines, masks, cuneiform tablets, and possibly unrecovered golden jewelry from known tombs before using destruction to mask the thefts.[75] Iraqi State Board of Antiquities official Qais Hussein Rashid reported targeted digging at Nimrud prior to the palace explosions on March 5-6, 2015, enabling the extraction of salable artifacts that funded ISIS operations.[75] Trafficked looted goods from Nimrud and comparable Iraqi sites were smuggled primarily via Turkey, then through the Balkans to auctions and private sales in Western Europe, the United States, and emerging Gulf markets, though major pieces rarely surfaced publicly due to hoarding by dealers.[75] This blend of iconoclastic demolition for propaganda and economic exploitation via selective theft parallels patterns at Hatra, where ISIS pulverized Parthian-era statues in 2015 after extracting smaller valuables, and Palmyra, where temple facades were blasted following the removal of marketable reliefs and the site's use for executions, demonstrating a consistent strategy of ideological erasure augmented by revenue generation.[76][74]Post-Conflict Recovery

Site Liberation and Initial Stabilization

Iraqi security forces liberated the Nimrud archaeological site from ISIS control on November 13, 2016, as part of the broader offensive to retake Mosul, approximately 30 kilometers to the north.[77][78] The site had been under ISIS occupation since mid-2014, during which militants conducted deliberate demolitions using explosives, bulldozers, and drills, reducing major structures like the Northwest Palace to rubble.[77] Following the military recapture, Iraqi forces established an initial security perimeter around the site, including patrols that deterred opportunistic looting and vandalism in the immediate aftermath.[79] UNESCO dispatched a rapid assessment team to Nimrud on December 14, 2016, to catalog visible damage and prioritize urgent interventions, confirming widespread structural instability from ISIS actions and prior neglect.[80] In early 2017, collaborative efforts between Iraqi antiquities officials and international partners, including the Smithsonian Institution's Nimrud Stabilization Project funded by the U.S. Department of State, focused on emergency measures such as erecting protective fencing, installing guard facilities, and propping unstable walls to prevent natural collapse exacerbated by blast damage.[79][81] These actions addressed immediate risks to remaining monumental architecture, including remnants of palaces and ziggurats, while facilitating preliminary documentation ahead of long-term recovery planning.[79]Ongoing Reconstruction and Recent Discoveries

Excavations conducted by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum) at Nimrud from 2023 to 2024 focused on the Ninurta Temple, yielding remarkably preserved shrines amid post-ISIS rubble. These shrines, including a dais and structural elements, survived due to burial under debris from the 2015 destruction, providing new insights into Neo-Assyrian religious architecture.[82][21] In spring 2024, the team completed uncovering a gate chamber linking the Ninurta and Ishtar temples, revealing detailed reliefs of military campaigns associated with Ashurnasirpal II.[83][84] In March 2025, the Iraqi government announced a comprehensive reconstruction plan for Nimrud, targeting the restoration of palaces and other structures damaged by ISIS demolitions. The initiative emphasizes site stabilization and partial rebuilding using original materials where possible, with an estimated timeline spanning a decade.[85] This effort builds on earlier stabilization but incorporates advanced documentation to guide repairs.[86] Throughout 2025, Iraqi archaeologists have reassembled over 500 fragmented artifacts from debris at the site, including bas-reliefs, sculptures, and decorated slabs depicting mythical creatures and Assyrian motifs from palaces. These pieces, shattered during the 2015 bulldozing and explosions, were cataloged and pieced together using forensic techniques, recovering elements previously thought irretrievable.[87][88] Such recoveries highlight selective survival amid destruction, with intact or minimally damaged items emerging from collapsed vaults.[89]International Collaboration and Security Measures

The British Institute for the Study of Iraq (BISI) has led the Nimrud Digitisation Project, compiling and preserving digital records of historical excavations, artifacts, and site documentation to mitigate risks from physical damage and facilitate future research amid ongoing threats.[90][36] Complementing this, the Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TAARII) convened the "A Future for Nimrud" conference series, including sessions in 2022–2024 on heritage stabilization, involving Iraqi officials and international experts to develop coordinated protection strategies and assess recovery needs post-ISIS occupation.[91] Iraqi military forces established a sustained presence at Nimrud after liberating the site in November 2016, installing perimeter fencing and basic fortifications to deter unauthorized access.[79] UNESCO supported these efforts through monitoring missions, including a rapid assessment in December 2016 that identified priorities for emergency safeguarding, such as tarpaulin coverings for exposed structures, contributing to a decline in reported illicit excavations by enhancing site oversight and local enforcement capacity.[80][92] Regional instability, including cross-border tensions and entrenched smuggling networks exploiting porous frontiers, continues to undermine these measures, with artifacts from Nimrud and similar sites appearing in illicit markets despite repatriation initiatives.[93] The Smithsonian Institution's Cultural Rescue Initiative provided additional stabilization aid, training Iraqi personnel in fortification techniques, though persistent security gaps highlight the limits of multinational coordination without broader geopolitical resolution.[79]Enduring Scholarly and Cultural Impact

Insights into Assyrian Imperial Achievements