Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kendang

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Inventor(s) | Indonesian (Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, Makassarese, Bugis)[1][2][3] |

|---|---|

| Developed | Indonesia[4][5] |

|

| Music of Indonesia |

| Genres |

|---|

| Specific forms |

|

|

|

|

| Regional music |

A kendang or gendang (Javanese: ꦏꦼꦤ꧀ꦝꦁ, romanized: kendhang, Sundanese: ᮊᮨᮔ᮪ᮓᮀ, romanized: kendang, Balinese: ᬓᬾᬦ᭄ᬤᬂ, romanized: kendang, Tausug/Bajau/Maranao: gandang, Bugis: gendrang and Makassar: gandrang or ganrang) is a two-headed drum used by people from the Indonesian Archipelago. The kendang is one of the primary instruments used in the gamelan ensembles of Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese music. It is also used in various Kulintang ensembles in Indonesia, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines. It is constructed in a variety of ways by different ethnic groups. It is related to the Indian double-headed mridangam drum.

Overview

[edit]The typical double-sided membrane drums are known throughout Maritime Southeast Asia and India. One of the oldest image of kendang can be found in ancient temples in Indonesia, especially the ninth century Borobudur and Prambanan temple.

Among the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese, the kendang has one side larger than the other, with the larger, lower-pitched side usually placed to the right, and the drums are usually placed on stands horizontally and hit with the hands on either side while seated on the floor. Amongst groups like the Balinese, Tausug, and Maranao, both sides are of equal size, and the drums are played on either one or both sides using a combination of hands and/or sticks.

In Gamelan music, the kendang is smaller than the bedug, which is placed inside a frame, hit with a beater, but used less frequently. The kendang usually has the function of keeping the tempo (laya) while changing the density (irama), and signaling some of the transitions (paralihan) to sections and the end of the piece (suwuk).

In the dance or wayang performance, the kendang player will follow the movements of the dancer, and communicate them to the other players in the ensemble. In West Java (Sundanese), kendang are used to keep the tempo of Gamelan Degung. Kendang are also used as main instrument for Jaipongan dances. In another composition called Rampak Kendang, a group of drummers play in harmony.

Among the Makassarese, the Ganrang (kendang) drums have much more importance, and they are considered the most sacred of all musical instruments, comparable to gongs in Java. This can be seen in local origin stories, accompaniments for local ceremonies, dances such as Ganrang Bulo, and martial arts. Even local government ceremonies are opened by the official sounding of a ganrang rather than the usual gong in Java. They are usually played alone with multiple drums playing different patterns creating syncopation. These traditions can be seen across lowland South Sulawesi with Bugis people also sharing similar reverence to the Gendrang.

Kendang making

[edit]Good kendang instruments are said to be made from the wood of jackfruit, coconuts or cempedak. Buffalo hide is often used for the bam (inferior surface which emits low-pitch beats) while soft goatskin is used for the chang (superior surface which emits high-pitch beats).

The skin is stretched on y-shaped leather or rattan strings, which can be tightened to change the pitch of the heads. The thinner the leather the sharper the sound.

Accompaniments

[edit]Javanese

[edit]In Gamelan Reog, kendhang are used to accompany the Reog Ponorogo art, and the sound produced by Kendhang Reog is very distinctive with the beat of "dang thak dhak thung glhang". The existence of Kendang Reog is currently the largest in the world of the existing types of Kendhang.

In Gamelan Surakarta, four sizes of kendhang are used:[6]

- Kendhang ageng, kendhang gede (krama/ngoko, similar to gong ageng in usage), or kendhang gendhing is the largest kendang, which usually has the deepest tone. It is played by itself in the kendhang satunggal (lit. "single drum") style, which is used for the most solemn or majestic pieces or parts of pieces. It is played with the kendhang ketipung for kendhang kalih (lit. "double drum") style, which is used in faster tempos and less solemn pieces.

- Kendhang wayang is also medium-sized, and was traditionally used to accompany wayang performances, although now other drums can be used as well.

- Kendhang batangan or kendhang ciblon[7] is a medium-sized drum, used for the most complex or lively rhythms. It is typically used for livelier sections within a piece. The word ciblon derives from a Javanese type of water-play, where people smack the water with different hand shapes to give different sounds and complex rhythms. The technique of this kendang, which is said to imitate the water-play,[8] is more difficult to learn than the other kendang styles.

- Kendhang ketipung is the smallest kendang, used with the kendang ageng in kendhang kalih (double drum) style.

Sundanese

[edit]In Sundanese Gamelan, a minimum set consists of three drums.[9]

- Kendang Indung (large drum)

- Kendang Kulanter, two (small drum). Kendang Kulanter is divided into two, namely the Katipung and the Kutiplak.

Many types of Sundanese Kendang are distinguished according to their function in accompaniment :

- Kendang Kiliningan

- Kendang Jaipongan

- Kendang Ketuk Tilu

- Kendang Keurseus

- Kendang Penca

- Kendang Bajidor

- Kendang Sisingaan and others.

Each type of drums in Sundanese music has a difference in size, pattern, variety, and motif.

Balinese

[edit]In Balinese Gamelan, there are two kendang:[10]

- Kendang wadon, the "female" and lowest pitched.

- Kendang lanang, the "male" and highest pitched.

Makassarese

[edit]Ganrang (Makassarese kendangs) can be divided to three types:[11]

- Ganrang Mangkasarak is the largest drums as a result it is also called Ganrang Lompo (largest drum in Makassarese language).These drums are usually used in important sacred ceremonies such as blessing for sultanate's heirlooms.

- Ganrang Pakarena are usually smaller with diameters measuring in 30–40 cm, which are usually used for Pakarena dance, which used 2-4 drums with differing beats and symbolizes the men's strength and vitality.

- Ganrang Pamancak are usually the smallest with diameters measuring in 20–25 cm, and used as martial arts accompaniments.

Buginese

[edit]Among the Bugis Gendrang there are two types of playing techniques based on the position of the gendrang. if the gendrang is placed on the player's lap it is called mappalece gendrang. If the players are standing with the gendrangs tied with a shoulder strap it is called maggendrang tettong, this position are usually used for sacred ceremony, or for entertainment like beating of rice mortars or mappadendang. There are generally three types of beats pattern in gendrang playing:[12]

- Pammulang patterns are usually the beginning as intro

- Bali Sumange are played afterwards which are usually more energetic

- Kanjara patterns are used afterward, as finale.

Gallery

[edit]-

Kendang of Java, one side is bigger than other.

-

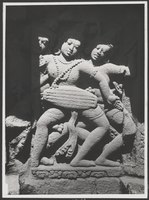

Bas-relief of kendang at Prambanan

-

Bas-relief of kendang at Prambanan

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- ^ 10 Alat Musik Kendang: Asal-Usul, Jenis, dan Cara Memainkannya[1]

- ^ Kendang Sunda[2]

- ^ 1994[3]

- ^ "Kendang - Instruments of the world". www.instrumentsoftheworld.com.

- ^ Kartomi, Margaret J.; Heins, Ernst; Ornstein, Ruby (2001). "Kendang". Kendang. Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.14877.

- ^ "Kendang".

- ^ https://omeka1.grinnell.edu/MusicalInstruments/exhibits/show/ens/item/82[dead link]

- ^ Lindsay, Jennifer (1992). Javanese Gamelan, p.22. ISBN 0-19-588582-1. "The technique of kendang ciblon is very difficult to acquire.[who?] Ciblon is the Javanese name for a type of water-play, popular in villages, where a group of people, through smacking the water with different hand-shapes, produce complex sounds and rhythmic patterns. These sounds are imitated on the dance drum."

- ^ Sunarto (2015). Kendang Sunda (in Indonesian). Penerbit Sunan Ambu Press, STSI Bandung. ISBN 978-979-8967-50-4.

- ^ "The Instruments for Gamelan Bali". Archived from the original on 2012-11-03. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ "Gandrang, Alat Musik Tradisional Makassar". 27 May 2015.

- ^ Rachmat, Rachmat; Sumaryanto, Totok; Sunarto, Sunarto (2020). "Klasifikasi Instrumen Gendang Bugis (Gendrang) Dalam Konteks Masyarakat Kabupaten Soppeng Sulawesi Selatan". Jurnal Pakarena. 3 (2): 40. doi:10.26858/p.v3i2.13064. S2CID 226030960.

Further reading

[edit]- Sumarsam. Javanese Gamelan Instruments and Vocalists. 1978–1979.