Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tausūg people

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Tausug (also spelled Tausog;[1] natively Tau Sūg, Jawi: تَؤُ سُوْݢْ) are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the Sulu Archipelago and northeastern coastal areas of Borneo, which spans present-day Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. Large Tausug populations are also found in the cities of mainland Mindanao, in particular Zamboanga City, Cotabato City and Davao City, and the island of Palawan.[11] Smaller Tausug populations can be found in Nunukan and Tarakan in North Kalimantan, Indonesia.[5][12][13][14]

Key Information

Following the introduction of Islam to the Sulu Archipelago in the 14th century, the Tausug established the Sultanate of Sulu, a thalassocratic state that exercised sovereignty over the islands that bordered the Zamboanga Peninsula in the east to Palawan in the north.[15] At its peak, it also covered areas further inland in northeastern Borneo and southwestern Mindanao.[16] During the Spanish colonial period of the Philippines, Tausug soldiers resisted repeated Spanish invasions and the Sultanate of Sulu remained a de facto independent state until 1915, following the Moro Rebellion which resulted in the state being annexed by the United States.

Following the independence of the Philippines in 1946, the Philippines has acted as the successor state of the Sultanate of Sulu, which has led to tensions with neighboring predominantly-Christian ethnic groups. Today, the Tausug form a part of the wider Muslim-majority Moro political identity in the Philippines, and have continued their shared struggle for self-determination. This has culminated in a decades-long insurgency in Mindanao, and a territorial dispute between Malaysia and the Philippines. In Malaysia, ethnic Tausug people are known by the exonym Suluk and have more recently formed a distinct socio-political identity from Tausug refugees arriving in Malaysia due to continued conflict in the southern Philippines.[17]

Etymology

[edit]The first half of the name Tausug derives from the Tausug word tau, meaning person.[18] The term sūg is widely accepted to derive from the word meaning sea current, with the definition of the whole name meaning “people of the [sea] currents”.[19]

Sūg is the modern form of the older term Sulug (meaning "[sea] currents"), which was also the old name of the island of Jolo. It is derived from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *sələg (“flowing water, current”), and is a cognate of Cebuano sulog, Tagalog silig, and Malay suluk.[20]

History

[edit]Pre-Islamic era

[edit]During the 13th century, the Tausug people began migrating to present-day Zamboanga and the Sulu archipelago from their homelands in northeastern Mindanao. William Scott (1994) calls the Tausugs the descendants of the ancient Butuanons and Surigaonons from the Rajahnate of Butuan, who moved south and established a spice trading port in Sulu. Sultan Batarah Shah Tengah, who ruled in 1600, was said to have been a native of Butuan.[21] The Butuanon-Surigaonon origin of the Tausugs is suggested by the relationship of their languages, as the Butuanon, Surigaonon and Tausug languages are all grouped under the Southern Visayan sub-family. Consequently, the Tausug language is closely related to other Southern Bisayan languages like the Butuanon language, which is still spoken in northeastern Mindanao to this day.[22]

Prior to the establishment of the sultanate, the Tausug lived in communities called banwa. Each banwa was headed by a leader known as a panglima along with a shaman called a mangungubat. The shaman could be either a man or a woman. Each banwa was considered an independent state, like other city-states in Asia. The Tausug of the era had trade relations with neighboring Tausug banwas, the Yakan people of Basilan, and the nomadic Sama-Bajau.

The Tausug were Islamized in the 14th century and established the sultanate of Sulu in the 15th century,[23][24] and eventually dominated the local Sama-Bajau people of the Sulu archipelago,

Sultanate era

[edit]

In 1380, the Sunni Sufi scholar Karim-ul Makhdum, a Muslim missionary of the Ash'ari Aqeeda and Shafi'i madhhab, arrived in Sulu. He introduced the Islamic faith and settled in Tubig Indangan in Simunul, where he lived until his death. The pillars of a mosque he had built at Tubig-Indangan still stand. In 1390, Rajah Baguinda Ali landed at Buansa, and continued the missionary work of Makhdum. The Johore-born Arab adventurer Sayyid Abubakar Abirin arrived in 1450, and married Baguinda's daughter, Dayang-dayang Paramisuli. After Rajah Baguinda's death, Sayyid Abubakar became sultan, thereby introducing the sultanate as a political system (see Sultanate of Sulu). Political districts were created in Parang, Pansul, Lati, Gitung, and Luuk, each headed by a panglima or district leader. After the Sunni Sufi scholar Sayyid Abubakar's death, the sultanate system had already become well established in Sulu. Before the coming of the Spaniards, the ethnic groups in Sulu — the Tausug, Samal, Yakan, and the Bajau – were united to varying degrees under the Sulu sultanate following the Sunni Islam, they were Ash'ari in aqeeda and Shafi'i in Madh'hab as well as practitioners of Sufism.[25]

The political system of the sultanate was patrilineal. The sultan was the sole sovereign of the sultanate, followed by various maharajah and rajah-titled subdivisional princes. Further down the line were the numerous panglima or local chiefs, similar in function to the modern Philippine political post of the barangay captain in the barangay system.

The Sulu Archipelago was an entrepôt that attracted merchants from south China and various parts of Southeast Asia beginning in the 14th century.[26] The name "Sulu" is attested in Chinese historical records as early as 1349,[27] during the late Yuan dynasty, suggesting trade relations around this time.[28] Trade continued into the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644), as envoys were sent in several missions to China to trade and pay tribute to the emperor. Sulu merchants often exchanged goods with Chinese Muslims, and there was also trade with Muslims who were of Arab, Persian, Malay, or Indian descent.[26] Islamic historian Cesar Adib Majul argues that Islam was introduced to the Sulu Archipelago in the late 14th century by Chinese and Arab merchants and missionaries from Ming China.[27][28] Moreover, these 7 Arab missionaries were called "Lumpang Basih" by the Tausug and they were Sunni Sufi Scholars from the Ba 'Alawi sada of Yemen.[29]

Around this time, a notable Arab judge, Sunni Sufi and religious scholar named Karim ul-Makhdum[note 1] from Mecca arrived in Malacca. He preached Islam, particularly the Ash'ari Aqeeda and Shafi'i Madh'hab as well as the Qadiriyya Tariqa to the people, and thus many citizens, including the ruler of Malacca, converted to Islam.[30] The Sulu leader Paduka Pahala and his sons moved to China, where he died, and Chinese Muslims brought up his sons in Dezhou, where their descendants live and have the surnames An and Wen. In 1380 AD,[note 2] Karim ul-Makhdum arrived in Simunul island from Malacca, again with Arab traders. Apart from being a scholar, he operated as a trader; some see him as a Sufi missionary originating from Mecca.[31] He preached Islam in the area, and was thus accepted by the core Muslim community. He was the second person who preached Islam in the area, following Tuan Mashā′ikha. To facilitate easy conversion of nonbelievers, he established a mosque in Tubig-Indagan, Simunul, which became the first Islamic temple to be constructed in the area, as well as the first in the Philippines. This later became known as Sheik Karimal Makdum Mosque.[32] He died in Sulu, although the exact location of his grave is unknown. In Buansa, he was known as Tuan Sharif Awliyā [33] On his alleged grave in Bud Agad, Jolo, an inscription reassure "Mohadum Aminullah Al-Nikad". In Lugus, he is referred to as Abdurrahman. In Sibutu, he is known by his name.[34]

The difference of beliefs on his grave location came about due to the fact that the Qadiri Shaykh Karim ul-Makhdum travelled to several islands in the Sulu Sea to preach Islam. In many places in the archipelago, he was beloved. It is said that the people of Tapul built a mosque honoring him and that they claim descent from Karim ul-Makhdum. Thus, the success of Karim ul-Makhdum of spreading Islam in Sulu threw a new light in Islamic history in the Philippines. The customs, beliefs and political laws of the people changed and customized to adopt the Islamic tradition.[35]

Sulu abruptly stopped sending tributes to the Ming in 1424.[28] Antonio Pigafetta, in his journals, records that the sultan of Brunei went and invaded Sulu in order subjugate the nation and retrieve the two sacred pearls Sulu pillaged from Brunei during earlier times.[36] A sultan of Brunei, Sultan Bolkiah, married a princess (dayang-dayang) of Sulu, Puteri Laila Menchanai, and they became the grandparents of the Muslim prince of Maynila, Rajah Matanda, as Manila was a Muslim city-state and vassal to Brunei before the Spanish colonized them and converted them from Islam to Christianity.[citation needed] Islamic Manila ended after the failed attack of Tarik Sulayman, a Muslim Kapampangan commander, in the failure of the Conspiracy of the Maharlikas, when the formerly Muslim Manila nobility attempted a secret alliance with the Japanese shogunate and Bruneiean sultanate (together with her Manila and Sulu allies) to expel the Spaniards from the Philippines.[37] Many Tausugs and other native Muslims of Sulu Sultanate already interacted with Kapampangan and Tagalog Muslims called Luzones based in Brunei, and there were intermarriages between them. The Spanish had native allies against the former Muslims they conquered like Hindu Tondo which resisted Islam when Brunei invaded and established Manila as a Muslim city-state to supplant Hindu Tondo.

Battles and skirmishes were waged intermittently from 1578 till 1898 between the Spanish colonial government and the Moros of Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.[citation needed] In 1578, an expedition sent by Governor Francisco de Sande and headed by Captain Rodriguez de Figueroa began the 300-year conflict between the Tausūgs and the Spanish authorities. In 1579, the Spanish government gave de Figueroa the sole right to colonize Mindanao. In retaliation, the Moro raided Visayan towns in Panay, Negros, and Cebu, for they knew the Spanish conscripted foot soldiers from these areas. Such Moro raids were repelled by Spanish and Visayan forces. In the early 17th century, the largest alliance, comprising Maranao, Maguindanao, Tausūg, and other Moro and Lumad groups, was formed by Sultan Kudarat or Cachil Corralat of Maguindanao, ruler of domains extending from the Davao Gulf to Dapitan on the Zamboanga peninsula. Several Spanish expeditions suffered defeat at their hands. In 1635, Captain Juan de Chaves erected a fort and established a settlement in Zamboanga. In 1637, Governor General Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera personally led an expedition against Kudarat, and temporarily triumphed over his forces at Lamitan and Iliana Bay. On 1 January 1638, Hurtado de Corcuera, with 80 vessels and 2000 soldiers, defeated the Moro Tausūg and occupied Jolo, mainly staying inside captured Cottas. A peace treaty was forged, but Spanish sovereignty over Sulu still had not been firmly established; the Tausūg abrogated the treaty in 1646 soon after the Spaniards occupiers departed.[38] It wasn't until 1705 that the sultanate renounced to Spain any sovereignty it had previously asserted over south Palawan, and in 1762 it similarly relinquished its claims over Basilan. During the last quarter of the 19th century, the sultanate formally recognized Spanish sovereignty, but these areas remained partially controlled by the Spanish, with their sovereignty limited to military stations, garrisons, and pockets of civilian settlements in Zamboanga and Cotabato (the latter under the Sultanate of Maguindanao). Eventually, as a consequence of their defeat in the Spanish–American War, the Spanish had to abandon the region entirely.[citation needed]

In 1737, Sultan Alimud Din I, advancing his own personal interests, entered into a "permanent" peace treaty with Governor General F. Valdes y Tamon; and in 1746, he befriended the Jesuits sent to Jolo by King Philip. The "permission" of Sultan Azimuddin-I (*the first heir-apparent) allowed Catholic Jesuits to enter Jolo, but his younger brother, Raja Muda Maharajah Adinda Datu Bantilan (*the second heir-apparent) argued against this, saying that he did not want the Catholic Jesuits to disturb or dishonor Islamic faith among the Moro in Sulu. The two brothers' disagreement eventually caused Sultan Azimuddin-I to depart Jolo, first removing to Zamboanga and eventually arriving in Manila 1748. Upon his departure, his brother Raja Muda Maharajah Adinda Datu Bantilan was proclaimed sultan, taking the name Sultan Bantilan Muizzuddin.

In 1893, amid succession controversies, Amir ul Kiram became Sultan Jamalul Kiram II, the title being officially recognized by the Spanish authorities. In 1899, after the defeat of Spain in the Spanish–American War, Colonel Luis Huerta, the last governor of Sulu, relinquished his garrison to the Americans. (Orosa 1970:25–30).

In northern Borneo, most citizen families residing in Sabah are generally-recognized to have lived in the area since the time of the sultanate.[39][note 3] Local North Borneo records indicate that during the period of British rule, a notable Bajau-Suluk warrior participated in the Mat Salleh Rebellion, participating in the conflict until his death. During the Second World War when the Japanese occupied the northern Borneo area, many Suluk people, along with ethnic Chinese emigrants, were massacred by Japanese soldiers during the Jesselton Revolt against the Japanese invasion and occupation.[citation needed]

The Tausug had a saying, "Mayayao pa muti in bukug ayaw in tikud-tikud" (It is preferable to see the whiteness of your bone due to wounds than whiten your heel from running away) and in magsabil "when one runs amuck and he is able to kill a nonbeliever and in turn gets killed for it, his place in heaven is assured."[40]

The Tausug waged parang sabil (holy war) for their land (Lupah Sug) and religion against the United States after Bud Bagsak and Bud Dahu and during the Moro National Liberation Front's struggle against the Philippines since 1972, with them being memorialized in tales of Parang Sabil like "The Story of War in Zambo" (Kissa sin Pagbunu ha Zambo about MNLF commander Ustadz Habier Malik's 2013 attack in Zamboanga.[41]

Some Tausug who went on parang sabil did it to redeem themselves in causes of dishonor (hiya).[42] Tausug believe the sabils gain divine protection and can be immune to bullets while going on their suicide attacks.[43] Tausug committed parrangsabil in 1984 at Pata island, 1974 at Jolo, 1968 at Corregidor island, 1913 at Bud Bagsak, 1911 at Bud Talipaw, 1911 and 1906 at Bud Dahu. Tausug believe that the rituals they undergo in preparation for magsasabil and parrangsabil will render them invulnerable to bulles, metal and sharp weapons and that Allah will protect them and determine their fate while using their budjak spears, barung and kalis against enemies like the Americans and Spanish.[44]

Baker Atyani an Arab journalist, was kidnapped by the Abu Sayyaf group. On 3 February 2013 Ustaz Habir Malik led the MNLF to fight against Abu Sayyaf and demanded they released the hostages. Jolo was burned by Philippines on 7 February 1974, Spanish on 29 February 1896 & 27–28 February 1851.[45]

On 5 April 2019 MNLF member Abdul was interviewed by Elgin Glenn Salomon and said about the battle of Jolo in 1974 between the Philippines and MNLF. “They could not defeat the people of Sulu. See the Japanese, the Americans, and the Spaniards! They cannot defeat the province of Jolo. Until now, they could not defeat…. See, they (MNLF) have three guns… At the age of 12, they already have a gun. Will the soldiers continue to enter their territory? The heavy-duty soldiers would die at their (MNLF) hands.”[46]

Modern era

[edit]Philippines

[edit]A "policy of attraction" was introduced, ushering in reforms to encourage Muslim integration into Philippine society. "Proxy colonialism" was legalized by the Public Land Act of 1919, invalidating Tausūg pusaka (inherited property) laws based on the Islamic Shariah. The act also granted the state the right to confer land ownership. It was thought that the Muslims would "learn" from the "more advanced" Christian Filipinos, and would integrate more easily into mainstream Philippine society. In February 1920, the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives passed Act No 2878, which abolished the Department of Mindanao and Sulu, and transferred its responsibilities to the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes under the Department of the Interior. Muslim dissatisfaction grew as power shifted to the Christian Filipinos. Petitions were sent by Muslim leaders between 1921 and 1924, requesting that Mindanao and Sulu be administered directly by the United States. These petitions were not granted. Realising the futility of armed resistance, some Muslims sought to make the best of the situation. In 1934, Arolas Tulawi of Sulu, Datu Manandang Piang and Datu Blah Sinsuat of Cotabato, and Sultan Alaoya Alonto of Lanao were elected to the 1935 Constitutional Convention. In 1935, two Muslims were elected to the National Assembly.

The Tausūg in Sulu fought against the Japanese occupation of Mindanao and Sulu during World War II and eventually drove them out. The Commonwealth sought to end the privileges the Muslims had been enjoying under the earlier American administration. Muslim exemptions from some national laws, as expressed in the administrative code for Mindanao, and the Muslim right to use their traditional Islamic courts, as expressed in the Moro Board, were ended. It was unlikely that the Muslims, who have had a longer cultural history as Muslims than the Filipinos as Christians, would surrender their identity. This incident contributed to the rise of various separatist movements – the Muslim Independence Movement (MIM), Ansar El-Islam, and Union of Islamic Forces and Organizations (Che Man 1990:74–75).Founders of the Ansarul Islam were Capt.Kalingalan Caluang, Rashid Lucman, Salipada Pendatun, Domocao Alonto, Hamid Kamlian, Udtog Matalam, Atty. Macapantun Abbas Jr.In 1969, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) was founded on the concept of a Bangsa Moro Republic by a group of educated young Muslims.The Chief Minister of Sabah by then was Tun Mustapha, he was like a brother and had good relations with Kalingalan “Apuh Inggal” Caluang. Through Tun Mustapha's help, the first fighters of MNLF(Like Al Hussein Caluang) were trained in Sabah after staying in Luuk, Sulu(which is now Kalingalan Caluang). Nur Misuari became a part of the Ansarul Islam because of his good reputation as a UP professor. After the training of these first MNLF fighters, Yahya Caluang(Son of Kalingalan “Apuh Inggal” Caluang) was asked by Kalingalan “Apuh Inggal” Caluang to fetch the MNLF fighters in Sabah. When Yahya Caluang arrived, Nur Misuari took over and declared himself Leader of the MNLF. Nur Misuari eventually asked forgiveness to Kalingalan “Apuh Inggal” Caluang and Apuh Inggal forgive him.[47]

In 1976, negotiations between the Philippine government and the MNLF in Tripoli resulted in the Tripoli Agreement, which provided for an autonomous region in Mindanao. Nur Misuari was invited to chair the provisional government, but he refused. The referendum was boycotted by the Muslims themselves. The talks collapsed, and fighting continued. On 1 August 1989, Republic Act 673 or the Organic Act for Mindanao, created the Autonomous Region of Mindanao, which encompasses Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi.[citation needed]

Malaysia

[edit]

Most of the Tausugs in Malaysia have been living in part of Saba since the rule of the sultanate of Sulu. Some of them actually descendants of a Sulu princess (Dayang Dayang) who escaped from the Sulu sultan in the 1850s, when the sultan tried to take the princess as a wife although he already had many concubines.[48] To differentiate themselves from the newly arrived Tausūg immigrants from the Philippines, most of them prefer to be called "Suluk".[49]

However, more recent Tausug immigrants and refugees dating back to the 1970s Moro insurgency (the majority of them illegal immigrants) often face discrimination in Sabah. After the 2013 Lahad Datu standoff, there were reports of abuses by Malaysian authorities specifically on ethnic Tausug during crackdowns in Sandakan, even on Tausūg migrants with valid papers.[50][51] Approximately nine thousand Filipino Tausūg were deported from January to November 2013.[52][53][54]

Demographics

[edit]

The Tausug number was of 1,226,601 in the Philippines in 2010.[55] They populate the Filipino province of Sulu as a majority, and the provinces of Zamboanga del Sur, Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga Sibugay, Basilan, Tawi-Tawi, Palawan, Cebu, and Manila as minorities. Many Filipino-Tausūgs have found work in neighboring Sabah, Malaysia as construction labourers in search of better lives. However, many of them violate the law by overstaying illegally and are sometimes involved in criminal activities.[49] The Filipino-Tausūgs are not recognized as a native to Sabah.[note 3][56]

The Tausugs who have already been living natively in Sabah by the time of the Sulu or Tausug sultanate have settled in much of the eastern parts, from Kudat town in the north, to Tawau in the south east.[39] They number around 300,000 and many of them have intermarried with other ethnic groups in Sabah, especially the Bajaus. Most prefer to use the Malay-language ethnonym Suluk in their birth certificates rather than the native Tausūg to distinguish themselves from their newly arrived Filipino relatives in Sabah. Migration fueled mainly from Sabah also created a substantial Suluk community in Greater Kuala Lumpur. While in Indonesia, most of the communities mainly settled in the northern area of North Kalimantan like Nunukan and Tarakan, which lies close to their traditional realm. There are around 12,000 (1981 estimate) Tausūg in Indonesia.[57]

Religion

[edit]The overwhelming majority of Tausūgs follow Islam, as Islam has been a defining aspect of native Sulu culture ever since Islam spread to the southern Philippines. They follow the traditional Sunni Shafi'i section of Islam, however they retain pre-Islamic religious practices and often practice a mix of Islam and Animism in their adat. A Christian minority exists. During the Spanish occupation, the presence of Jesuit missionaries in the Sulu Archipelago allowed for the conversion of entire families and even tribes and clans of Tausūgs, and other Sulu natives to Christianity. For example, Azim ud-Din I of Sulu, the 19th sultan of Sulu was converted to Christianity and baptized as Don Fernando de Alimuddin, however he reverted to Islam in his later life near death.

Some of the assimilated Filipino celebrities and politicians of Tausūg descent also tend to follow the Christian religion of the majority instead of the religion of their ancestors. For example, Maria Lourdes Sereno, the 24th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines is of patrilineal Tausūg descent is a born-again Christian. Singer Sitti is of Tausūg and Samal descent (she claims to be of Mapun heritage, also native to Sulu), is also a Christian.

The Tausug used to be Hindus before converting to Islam.[58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][excessive citations] Najeeb Saleeby described them as still retaining Hindu practices.[78] Saleeby said the Moros were ignorant of Islamic tenets, barely prayed or went to the mosque and their juramentados were not fueled by religion but by nationalism against the occupying enemy.[79][80]

Tausug retain pre-Islamic practices in the form of folk-Islam like the pagkaja and other palipalihan, as mentioned by Samuel K. Tan, some of these practices were allowed by the majority of the Ulama like the former Grand Mufti of Region 9 and Palawan Sayyiduna Shaykh AbdulGani Yusop since the Muslims in the Philippines were Ash'ari in Aqeeda, Shafi'i in Fiqh and practitioners of Sufism.[81]

IAS/ UNOPS/UNFPA/IFAD representative Dr. P. V. Ramesh saw Professor Nur Misuari's MNLF in General Santos City perform Ramayana during a ceasefire agreement.[82]

Traditional political structure

[edit]The political structure of the Tausug is affected by the two economic divisions in the ethnic group, mainly parianon (people of the landing) and guimbahanon (hill people).[83] Before the establishment of the sultanate of Sulu, the indigenous pre-Islamic Tausug were organized into various independent communities or community-states called banwa. When Islam arrived and the sultanate was established, the banwa was divided into districts administered by a panglima (mayor). The panglima are under the sultan (king). The people who held the stability of the community along with the sultan and the panglimas are the ruma bichura (state council advisers), datu raja muda (crown prince), datu maharaja adensuk (palace commander), datu ladladja laut (admiral), datu maharaja layla (commissioner of customs), datu amir bahar (speaker of the ruma bichara), datu tumagong (executive secretary), datu juhan (secretary of information), datu muluk bandarasa (secretary of commerce), datu sawajaan (secretary of interior), datu bandahala (secretary of finance), mamaneho (inspector general), datu sakandal (sultan's personal envoy), datu nay (ordinance or weapon commander), wazil (prime minister). A mangungubat (curer) also has special status in the community as they are believed to have direct contact with the spiritual realm.

The community's people is divided into three classes, which are the nobility (the sultan's family and court), commoners (the free people), and the slaves (war captives, sold into slavery, or children of slaves).[84]

Languages

[edit]

The Tausug language is called "Sinug" with "Bahasa" to mean Language. The Tausug language is related to Bicolano, Tagalog and Visayan languages, being especially closely related to the Surigaonon language of the provinces Surigao del Norte, Surigao del Sur and Agusan del Sur and the Butuanon language of northeastern Mindanao specially the root Tausug words without the influence of the Arabic language, sharing many common words. The Tausūg, however, do not consider themselves as Visayan, using the term only to refer to Christian Bisayan-language speakers, given that the vast majority of Tausūgs are Muslims in contrast to its very closely related Surigaonon brothers which are predominantly Roman Catholics. Tausug is also related to the Waray-Waray language.[citation needed] Aside from Tagalog (which is spoken throughout the country), a number of Tausug can also speak Zamboangueño Chavacano (especially those residing in Zamboanga City), and other Visayan languages (especially Cebuano language because of the mass influx of Cebuano migrants to Mindanao); Malay in the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia; and English in both Malaysia and Philippines as second languages.[citation needed]

Malaysian Tausūg, descendants of residents when the Sulu Sultanate ruled the eastern part of Sabah, speak or understand the Sabahan dialect of Suluk, Malaysian language, and some English or Sinama (those who come in regular contact with the Bajau also speak Bajau dialects). By the year 2000, most of the Tausūg children in Sabah, especially in towns of the west side of Sabah, were no longer speaking Tausūg; instead they speak the Sabahan dialect of Malay and English.[citation needed]

Indonesian Tausūg on the other hand, are descendants of residents when the Sultanate of Bulungan, a vassal state of the Sulu Sultanate, also ruled the southeastern part of Sabah (Tawau) and the Indonesian province of North Kalimantan (northeastern portion), also speak or understand the Nunukan dialect of Suluk, Indonesian language (including colloquial variant) and as well as the regional slang. At the same time, they can also understand and speak the Suluk dialect spoken in Sabah as well as Sabah Malay.

| English | Tausug | Surigaonon | Cebuano |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is your name? | Hisiyu in ngān mu? | Unu an ngayan mu? | Unsa'y ngalan nimo? |

| My name is Muhammad | In ngān ku Muhammad | An ngayan ku ay Muhammad | Ang ngalan nako ay Muhammad |

| How are you? | Maunu-unu nakaw? | Ya-unu nakaw? | Kumusta ka? |

| I am fine, [too] | Marayaw da [isab] | Madayaw da [isab] aku (Tandaganon)/Marajaw da [isab] aku (Surigaonon) | Maayo da/ra [usab] 'ko |

| Where is Ahmad? | Hawnu hi Ahmad? | Hain si Ahmad? | Asa si Ahmad? |

| He is in the house | Ha bāy siya | Sa bay siya/sija | Sa balay siya |

| Thank you | Magsukul | Salamat | Salamat |

| ‘I am staying at’ or ‘I live at’ | Naghuhula’ aku ha | Yaghuya aku sa | Nagpuyo ako sa |

| I am here at the house. | Yari aku ha bay. | Yadi aku sa bayay. | Dia ra ko sa balay. |

| I am Hungry. | Hiyapdi' aku. | In-gutom aku. | Gi-gutom ku. |

| He is there, at school. | Yadtu siya ha iskul. | Yadtu siya/sija sa iskul. | Atoa siya sa tunghaan/skwelahan |

| Fish | Ista' | Isda | Isda/ita |

| Leg | Siki | Siki | Tiil |

| Hand | Lima | Alima | kamut |

| Person | Tau | Tau | Taw/tawo |

| (Sea/River) current | Sūg | Sūg | Sūg/Sulog |

| Fire | Kāyu | Kayajo | Kalayo |

| Shrimp/Prawn | Ullang | Uyang | Pasayan |

| Ear | Taynga | Talinga | Dalunggan |

| Face | Bayhu' | Wayong | Nawong |

| Rain | Ulan | Uyan | Ulan |

| Morning | Mahinaat/Maynat | Buntag | Buntag |

| Mosquito | Hilam | Hilam | Lamok |

| House/Home | Bāy | Bayay | Balay |

| Dog | Iru' | Ido | Iro |

| Year | Tahun | Tuig | Tuig |

| Month/Moon | Bulan | Buyan | Bulan |

| Male/Man/Lad | Usug | Layaki | Lalaki/Laki |

| Now | Bihaun | Kuman | Karon |

| Far/Distant | Malayu' | Lajo | Layo |

| Sleep | Tūg | Tuyog | Tulog |

| Sea Urchin | Tayum | Tajum | Tuyom |

| Medicine | Ubat | Tambay | Tambal |

| Shame | Sipug | Sipog | Ulaw/Kaulaw |

| Male genitalia | Utin | Utin | Utin |

| Heat | Pasu' | Paso | Init/Kaigang |

| Nice | Malingkat | Kagana | Nindot |

| I don't know/think so | Inday | Inday | Ambot |

| Don't (imperative) | Ayaw | Jagot | Ayaw |

| Rust | Gaha' | Kalaying | Taya |

| Knowledgeable | Maingat | Hibayo | Kahibawo/Kahibalo |

| Come in/Enter | Sūd | Dayon | Sulod |

| Butt/Buttocks | Buli' | Labot | Lubot |

| Underarms | Iluk | Ilok | Ilok |

| Flower | Sumping | Buyak | Bulak |

| Widow | Balu | Bayo | Balo |

| Mouse/Rat | Ambaw | Ambaw | Ilaga |

| Cow | Sapi' | Baka | Baka |

| Thunder | Dawgdug | Dayugdog | Dalugdog |

| Rich | Dayahan | Datu | Kwartahan/Dato |

| Gay/Effeminate/Homosexual | Bantut | Bayot | Bayot |

| Cat | Kuting | Miya | Iring |

| Said | Lawng | Laong | Ingon |

| Ugly | Mangi' | Kayaot | Bati |

| Right | Amu | Amo | Mao |

| Separated | Butas | Buyag | Bulag |

| Gold | Bulawan | Bujawan | Bolawan |

| Lanzones/Langsat (Lansium domesticum) | Buwahan | Buwahan | Buwahan |

| Sweat | Hulas | Huyas | Singot |

| Road/Path/Way | Dān | Dayan | Dalan |

| Money | Sīn/Pilak | Puya | Kwarta |

| Woman | Babai | Babaje/Baje | Babaye/Baye |

| Turn | Biluk | Bijok/Liso | Tuyok |

| Dress | Badju' | Baro | Sanina/Bado |

| Elderly | Maas | Tiguyang | Tigulang |

| If | Bang | Kun | Kung/Kon |

| Spices | Pamāpa | Jaman | Lamas |

| Bamboo | Patung/Kayawan | Kawajan | Kawayan |

| Climb | Dāg | Kayatkat | Katkat |

| Walk | Panaw | Panaw | Lakaw |

| Relatives | Anak kampung | Lumon | Parinte |

| Go outside | Guwa' | Lugwa | Gawas |

| Dirty | Malummi' | Lipa | Hugaw |

| Go with | Iban | Iban | Uban |

| Different | Dugaing/Kandī | Kala-in | Lain |

| Airplane/Aircraft | Ariplanu/Passawat/Kappal lupad/Kappal Tarbang | Idro | Eroplano |

| Car/Automobile | Awtu/Karita'/Mubil | Awto | Awto |

| Husband | Bana | Bana | Bana |

| Technician/Repair crew | Magdarayaw | Mandajaway | Mang-ayuhay |

| Aim/Purpose/Intention | Maksud | Tujo | Tuyo |

| Drunk | Hilu | Bayong | Hubog |

| Dove/Pigeon | Assang/Mapāti | Kayapati | Kalapati |

| Tiger | Halimaw | Tigre | Tigre |

Cultures

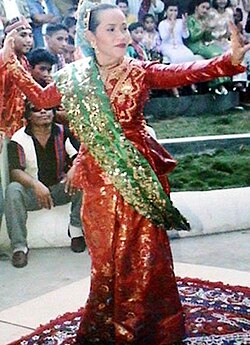

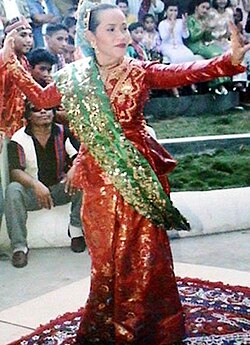

[edit]Tausūgs are superb warriors and craftsmen. They are known for the Pangalay dance (also known as Daling-Daling in Sabah), in which female dancers wear artificial elongated fingernails made from brass or silver known as janggay, and perform motions based on the Vidhyadhari (Bahasa Sūg: Bidadali) of pre-Islamic Buddhist legend. The Tausug are also well known for their pis syabit, a multi-colored woven cloth traditionally worn as a headress or accessory by men. Nowadays, the pis syabit is also worn by women and students. In 2011, the pis syabit was cited by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts as one of the intangible cultural heritage of the Philippines under the traditional craftsmanship category that the government may nominate in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[85] The Tausug are additionally associated with tagonggo, a traditional type of kulingtang music.[86]

Both cross cousin marriage and paternal parallel cousin marriage are practiced by Tausug Moro Muslims.[87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96]

-

Filipino-Americans from NYC-based dance company Kinding Sindaw dressed in Tausug attire.

-

Filipino-Americans from NYC-based dance company Kinding Sindaw dressed for a traditional Maranao, not Tausug, fan dance.

-

A Tausug man wearing traditional attire that consists of badjuh lapih (upper) and kupat (pants).

-

A Tausug woman wearing a sablay.

-

Kabasi, a Tausūg dish.

-

Pis siyabit (headscarf) of the Tausūgs, displayed at the Honolulu Museum of Art.

Notable Tausūgs

[edit]

- Santanina T. Rasul, first Filipino Muslim woman senator.

- Muedzul Lail Tan Kiram, legitimate sultan of Sulu Filipino

- Nur Misuari, former Filipino governor and became the leader of the Moro National Liberation Front.

- Hadji Kamlon, freedom fighter

- Panglima Bandahala, trusted adviser and close relative of the Sultan Jamalul Kiram II, he held significant positions such as Municipal President and peace emissary

- Sayyid Captain Kalingalan "Apuh Inggal" Caluang, son of Caluang son of Panglima Bandahala son of Sattiya Munuh son of Sayyid Qasim, one of the Fighting 21 of Sulu.[97] he was one of the founders of Ansar El Islam (Helpers of Islam) along with Domocao Alonto, Rashid Lucman, Salipada Pendatun, Hamid Kamlian, Udtog Matalam, and Atty. Macapantun Abbas Jr. Accordingly, "it is a mass movement for the preservation and development of Islam in the Philippines".[98]

- Jamalul Kiram III, pretender or self-proclaimed Sultan of Sulu.

- Ismael Kiram II, descendant Filipino sultan.

- Mat Salleh (Datu Muhammad Salleh), Sabah warrior from Inanam who led the Mat Salleh Rebellion until his death.

- Tun Datu Mustapha (Tun Datu Mustapha bin Datu Harun), first Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) of Sabah and third Chief Minister of Sabah.

- Juhar Mahiruddin, tenth Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) of Sabah (also partial Kadazan-Dusun ethnic ancestry).

- Shafie Apdal, fifteenth Chief Minister of Sabah.

- Sitti, Filipino singer.

- Abdusakur Mahail Tan, Governor of Sulu.

- Miguel "Miggy" Cabel Moreno, Chef and Cultural Advocate

- Maria Lourdes Sereno, 24th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines.

- Darhata Sawabi, Filipino weaver known for pis syabit, a traditional Tausūg cloth tapestry. She is a recipient of the Philippine National Living Treasures Award.[99]

- Yong Muhajil, YouTube vlogger and 3rd runner up in Pinoy Big Brother: Lucky 7.

- Omar Musa, author, poet, and rapper.

- Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani, Jihadist leader and founder of Abu Sayyaf (also partial Ilonggo ethnic ancestry).

- Khadaffy Janjalani, Jihadist and leader of Abu Sayyaf. He was a younger brother of Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani.

- Jainal Antel Sali Jr., Senior leader of Abu Sayyaf.

- Albader Parad, Senior leader of Abu Sayyaf.

- Hajan Sawadjaan, Leader of Abu Sayyaf.

- Radullan Sahiron, Leader of Abu Sayyaf.

- Hussin Ututalum Amin, mayor of Jolo.

- Mohammad Mahakuttah Abdullah Kiram, legitimate 34th Sultan of Sulu and father of Muedzul Lail Tan Kiram.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ May be interchange to Karimul Makhdum, Karimal Makdum or Makhdum Karim among others. Makhdum came from the Arabic word makhdūmīn, which means "master".

- ^ Another uncertain date in Philippine Islamic history is the year of arrival of Karim ul-Makhdum. Though other Muslim scholars place the date as simply "the end of 14th century", Saleeby calculated the year as 1380 AD corresponding to the description of the tarsilas, in which Karim ul-Makhdum's coming is 10 years before Rajah Baguinda's. The 1380 reference originated from the event in Islamic history when a huge number of makhdūmīn started to travel to Southeast Asia from India. See Ibrahim's "Readings on Islam in Southeast Asia."

- ^ a b Most of the native Suluks in Sabah have lived there since before the formation of Malaysia. At that time, everyone living within Malaysian borders automatically gained citizenship, as contrasted with later immigrants from the Philippines arriving after the country had been formed.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". National Statistics Office. Philippine Statistics Authority. 4 July 2023. Archived from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ Maraining, Amrullah; Othman, Zaini; Mohd Radzi, Marsitah; Abdul Rahim, Md Saffie (31 December 2018). "Komuniti Suluk dan Persoalan Migrasi: 'Sirih Pulang ke Gagang'" [The Community of Sulu and the Issue of Migration]. Jurnal Kinabalu (in Malay). 24: 44. doi:10.51200/ejk.v24i.1678 (inactive 1 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Patricia Regis; Anne Lasimbang; Rita Lasimbang; J. W. King. "Introduction to Integration of Indigenous Culture into Non-Formal Education Programmes in Sabah" (PDF). Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Development, Partners of Community Organisations (PACOS), Kadazandusun Language Foundation and Summer Institute of Linguistics, Malaysia Branch, Sabah. Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (Japan). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ Johari, Shafizan (9 March 2013). "Cara hidup orang Suluk di Lahad Datu" [The way of life of the Suluk people in Lahad Datu] (in Malay). Astro Awani. Archived from the original on 28 December 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ a b Zudiant, Hardian (1981). "Languages of Indonesia". Ethnologue.

- ^ Zulyani Hidayah (28 April 2020). A Guide to Tribes in Indonesia: Anthropological Insights from the Archipelago. Springer Nature Singapore Pte.Ltd. p. 322. ISBN 978-981-15-1834-8.

- ^ "Tausug Cultural Orientation, Chapter 2: Religion". dliflc.edu. Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Nocum, Arizza (29 May 2019). "Growing up both Muslim and Catholic in the Philippines". GMA News Online. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Minorities and indigenous people in the Philippines: Moro Muslims". Minorityrights.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Jumala, Francis C. (2019). "In Fulfilment of the Janji: Some Social Merits of the Tausug Pagkaja" (PDF). International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. 9 (9). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Anudin, Ali G. (September 2019). "Ethnolinguistic vitality assessment of the Tausug language of Zamboanga City". La Salle University. Animo Repository. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Eko Wahyudi (ed.). "Suku-suku di Provinsi Kalimantan Utara: Ada Suku Tidung yang Gambarnya ada di Uang Pecahan Rp75.00,00". Palembang Express. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Kalimantan Utara Archives". Indonesia Kaya.

- ^ Faozan Tri Nugroho, ed. (29 November 2022). "Daftar Suku Bangsa dari Setiap Provinsi di Indonesia". Bola.com. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Hernandez, Jose Rhommel B. (2016). "The Philippines: Everything in place". In Lee Lai To; Zarina Othman (eds.). Regional Community Building in East Asia: Countries in Focus. Taylor & Francis. pp. 142–143. ISBN 9781317265566.

- ^ Saunders, Graham (5 November 2013). A History of Brunei. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-136-87394-2.

- ^ Doksil, Mariah (25 March 2013). "Early Suluk residents here are legally Malaysian – director". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth R. (9 October 2019). "Waves of migration, old and new". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Salvador, Jinggoy I. (13 August 2021). "The Kadayawan Festival and the 11 tribes of Davao". SunStar. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Saleeby 1908, p. 133.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture And Society. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 164. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Zorc, R. David Paul. "Glottolog 3.3 – Tausug". Glottolog. Retrieved 12 March 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Alfred Kemp Pallasen (1985). Culture Contact and Language Convergence (PDF). LSP Special Monograph Issue 24. Linguistic Society of the Philippines. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2015.

- "early history (1400s)". 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ Rodney C. Jubilado (2010). "On cultural fluidity: The Sama-Bajau of the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas". Kunapipi. 32 (1): 89–101.

- ^ Morales, Yusuf (18 June 2017). "PEACETALK: The different Islamic schools of thought in the Philippines". MindaNews. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ a b Donoso 2022, p. 505

- ^ a b Abinales & Amoroso 2005, p. 43

- ^ a b c Gunn 2011, p. 93

- ^ Quiling, Mucha-Shim (2020). "Lumpang Basih". Journal of Studies on Traditional Knowledge in Sulu Archipelago and Its People, and in the Neighboring Nusantara. 3. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ Saleeby 1908, pp. 158–159

- ^ Larousse 2001, p. 40

- ^ Mawallil, Amilbahar; Dayang Babylyn Kano Omar (3 July 2009). "Simunul Island, Dubbed As 'Dubai of the Philippines', Pursues Ambitious Project". The Mindanao Examiner. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Ibrahim, Ahmad; Siddique, Sharon; Hussain, Yasmin (1985), Readings on Islam in Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 51, ISBN 978-9971-988-08-1

- ^ Gonda 1975, p. 91

- ^ Saleeby 1908, p. 159

- ^ Brunei Rediscovered: A Survey of Early Times By Robert Nicholl Page 45.

- ^ de Marquina, Esteban (1903). Blair, Emma Helen; Robertson, James Alexander (eds.). Conspiracy Against the Spaniards: Testimony in certain investigations made by Doctor Santiago de Vera, president of the Philipinas, May–July 1589. Vol. 7. Ohio, Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company. pp. 86–103.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Cf. also Paulo Bonavides, Political Sciences (Ciência Política), p. 126. [verification needed]

- ^ a b "Sabah's People and History". Sabah State Government. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

The Kadazan-Dusun is the largest ethnic group in Sabah that makes up almost 30% of the population. The Bajaus, or also known as "Cowboys of the East", and Muruts, the hill people and head hunters in the past, are the second and third largest ethnic group in Sabah respectively. Other indigenous tribes include the Bisaya, Brunei Malay, Bugis, Kedayan, Lotud, Ludayeh, Rungus, Suluk, Minokok, Bonggi, the Ida'an, and many more. The largest non-indigenous group of the population are Chinese.

- ^ Apron, Jeremiah. "Tausug: People of the Current". p. 5.

- ^ Ingilan, Sajed S.; Abdurajak, Nena C. (2021). "Unveiling the Tausug Culturein Parang Sabil through Translation". Southeastern Philippines Journal of Research and Development. 26 (2): 97–108. doi:10.53899/spjrd.v26i2.156.

- ^ Lluisma, Ysa Tatiana (February 2011). The Redemption of the Parang Sabil: A Rhetorical Criticism of the Tausug Parang Sabil Using Burke's Dramatist Pentad (Bachelor of Arts in Speech Communication thesis). Department Of Speech Communication and Theatre Arts at the University of the Philippines. p. 46.

- ^ Lluisma, Ysa Tatiana (February 2011). The Redemption of the Parang Sabil: A Rhetorical Criticism of the Tausug Parang Sabil Using Burke's Dramatist Pentad (Bachelor of Arts in Speech Communication thesis). Department Of Speech Communication and Theatre Arts at the University of the Philippines. p. 66.

- ^ Jolo, Neldy. "TAUSUG INVULNERABILITY". pp. 1–3.

- ^ Jolo, Neldy. "TAUSUG: STILL A BRAVE PEOPLE?".

- ^ Salomon, Elgin Glenn (2022). "Testimonial Narratives of Muslim Tausug Against Militarization of Sulu (1972-1974)". Studia Islamika. 29 (2): 261. doi:10.36712/sdi.v29i2.23131 (inactive 13 September 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2025 (link) - ^ Espaldon, Senator Ernesto (1997). WITH THE BRAVEST The Untold Story of the Sulu Freedom Fighters of World War II. p. 210. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ Philip Golingai (26 May 2014). "Despised for the wrong reasons". The Star. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ a b Daphne Iking (17 July 2013). "Racism or anger over social injustice?". The Star. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Saceda, Charlie (6 March 2013). "Pinoys in Sabah fear retaliation". Rappler. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Manlupig, Karlos (9 March 2013). "If you are Tausug, they will arrest you". Rappler. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Deported Filipinos forced to leave families". Al Jazeera. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "11,992 illegals repatriated from Sabah between January and November, says task force director". The Malay Mail. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Jaymalin Mayen (25 March 2014). "Over 26,000 Filipino illegal migrants return from Sabah". The Philippine Star. ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) – Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Fausto Barlocco (4 December 2013). Identity and the State in Malaysia. Routledge. pp. 77–85. ISBN 978-1-317-93239-0.

- ^ "Languages of Indonesia | PDF | Java | Bali". Scribd. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Saleeby 1908, p. 44

- ^ Philippines. Division of Ethnology (1908). Division of Ethnology Publications, Volume 4, Part 2. Division of Ethnology Publications, Philippines. Division of Ethnology. Bureau of Printing. p. 152.

In conPage 5 is a copy of a Sulu document issued by Sultan Jamalul - Kiram I in the year 1251 A. H., or about seventy ... The first person who lived on the Island of Sulu is Jamiyun Kulisa . ... 5 One of the names of the wife of Vishnu ...

- ^ Philippines. Bureau of Science. Division of Ethnology (1905). Publications, Volume 4. p. 152.

Page 5 is a copy of a Sulu document issued by Sultan Jamalul - Kiram I in the year 1251 A. H., or about seventy - three years ago . It confers the title of Khatib or Katib ? on a Sulu pandita ? named Adak . ... the wife of Vishnu .

- ^ Sulu Studies, Volume 3. Sulu studies, Notre Dame of Jolo College. Coordinated Investigation of Sulu Culture. Contributors Notre Dame of Jolo College. Coordinated Investigation of Sulu Culture, Notre Dame of Jolo College. Notre Dame of Jolo College. 1974. p. 152.

Mohammad Daud Abdul, a research assistant of the Coordinated Investigation of Sulu Culture ( CISC ) collaborated with ... A vehicle of Vishnu, he is " depicted with a white face, red wings and body of gold "; he " became famous in ...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ The Kadatuan I Conference Proceedings. Contributor University of the Philippines. Unibersidad ng Pilipinas. 1997. p. 52.

The political institutions of pre - Islamic Sulu and Mindanao were patriarchal in form, resembling in many ways the ... Sulu and Mindanao were Hindu - influenced, especially if we deduce that Vitnuism, the cult of God Vishnu or ...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rasul, Jainal D. (1999). Rasul, Al-Gazel (ed.). Still Chasing the Rainbow: Selected Writings of Jainal D. Rasul, Sr. on Filipino Muslims' Politics, History, and the Law (Shari'ah). FedPil Pub. p. 286.

From these sources, it is clear that the original inhabitants of pre - Islamic Sulu and Mindanao were Hindu - influenced, especially if we deduce that Vitnuism, the cult of God Vishnu or Narayena, was evidently practised .

- ^ Frothingham, Robert (1925). Around the World: A Friendly Guide for the World Traveler. Park Street library of letters, diaries and memoirs. Houghton Mifflin. p. 319.

- ^ Galang, Zoilo M. (1936). Galang, Camilo; Osias (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Philippines: Education and religion. Vol. 5 of Encyclopedia of the Philippines: The Library of Philippine Literature, Art and Science, Zoilo M. Galang. Philippine Education Company. p. 504.

- ^ Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research in Archaeology, History, Literature, Languages, Folklore Etc. Times of India. 1872. p. 331.

... ( verse 82 of my MS ) where it is said : -Ohu bê sulu Siri Sanga - bo raja Piyangul - wehera âdi wihâra karawâ Dewnuwara Dew ... Vishnu commonly called in this ( Anuradhapura ) district, ' Utpala waruna diwya rajayan wahanse ...

- ^ Scribe I Am (2014). Terrah: Damnation. X libris Corporation. ISBN 978-1493136483.

Vishnu, Sokol, Thor, Zeus, Baal, Sulu, Diva, Hawk and Lark Squadrons took off, all except the suspiciously absent Hunters. It was only as the pilots of the Solitude's fighter wings filled the airwaves with their chatter, that the truth ...

- ^ Saleeby 1908, p. 47

- ^ Philippines. Division of Ethnology (1905). Publications, Volume 1, Part 4. Division of Ethnology Publications, Philippines. Division of Ethnology. p. 155.

CHAPTER III RISE AND PROSPERITY OF SULU SULU BEFORE ISLAM ور The Genealogy of Sulu is a succinct analysis of the tribes or ... the highest places in its pantheon to Indra, the sky; Agni, the fire; Vayu, the wind; Surya, the sun .

- ^ Philippines. Division of Ethnology (1908). Division of Ethnology Publications, Volume 4, Part 2. Division of Ethnology Publications, Philippines. Division of Ethnology. Bureau of Printing. p. 155.

RISE AND PROSPERITY OF SULU SULU BEFORE ISLAM The Genealogy of Sulu is a succinct analysis of the tribes or elements which ... the highest places in its pantheon to Indra, the sky; Agni, the fire; Vayu, the wind; Surya, the sun .

- ^ Boomgaard, Peter, ed. (2007). A World of Water: Rain, Rivers and Seas in Southeast Asian Histories. NUS Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-9971693718.

... 113, 118, 131-2, 283 Sulu 31, 42, 127-9, 131-3, 148, 172 Sulu Archipelago see Sulu Islands Sulu Islands 36 ... 338, 345-6 Surapura 248 Surat 39 Surigao 171 Surya Agung Kertas ( SAK ) 328 Sutherland, Heather 4 Swahili coast ...

- ^ Galang, Zoilo M., ed. (1950). Encyclopedia of the Philippines: Religion. Vol. 10 of Encyclopedia of the Philippines, Zoilo M. Galang (3 ed.). E. Floro. p. 50.

... the highest places in its pantheon to Indra, the sky; Agui, the fire; Vayu, the wind; Surya, the sun . ... married the daughter of Raja Sipad the Younger, Iddha, ' and became the forefather of the principal people of Sulu .

- ^ Galang, Zoilo M., ed. (1957). Encyclopedia of the Philippines: History. Vol. 15 of Encyclopedia of the Philippines, Zoilo M. Galang (3 ed.). E. Floro. p. 45.

- ^ Fernando-Amilbangsa, Ligaya (2005). Ukkil: Visual Arts of the Sulu Archipelago (illustrated ed.). Ateneo University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9715504809.

... Vayu ( wind ), and Surya ( sun ) . These elements were probably worshipped by the ancient peoples of the Sulu Archipelago whose former religion is presumed to be of Hindu origin ( Saleeby, 1963 : 38 ), now obscured by Islam .

- ^ Balfour, Edward (1885). The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial Industrial, and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures, Volume 3 (3 ed.). Bernard Quaritch. p. 1188.

Sringa takamu, TEL ., Trapa bispi- Su - hoh - hiang, C'HIN ., Storax, Rose Surya - kund - Tapta - kund . maloes . Suryavansa . See Orissa; Solar Race . Sringeri . See Adwaita . Sulu, LEPCH ., Inuus rhesus . Susa in Khuzistan .

- ^ Cerdas jelajah Internet. Niaga Swadaya. p. 110. ISBN 9791477655.

Tangan, Melan Surya Sulu Ouh aku bingung Tidak tau harus bagaimana mengatakannya pada suami ku . Baru beberapa hari kemarin dia menikahiku, dan sekarang aku resmi menjadi Cyberlove, Selingku Bukan Ya ? Jangan Lupa Jemurannya Helloow ...

- ^ Surya, Hendra (May 2007). Reinhart: Titisan Lima Ksatria Agung Eirounos. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. p. 54. ISBN 978-6024333447.

Titisan Lima Ksatria Agung Eirounos Hendra Surya. Jenderal Sulu terdiam mendengar keluhan Raja Bian, dia tak dapat memungkiri kenyataan yang dikatakan Raja Bian. "Kini apa yang harus kami lakukan, Baginda?" tanya Teguilla memberanikan ...

- ^ Marr1, Timothy (2014). "Diasporic Intelligences in the American Philippine Empire: The Transnational Career of Dr. Najeeb Mitry Saleeby". Mashriq & Mahjar. 2 (1). doi:10.24847/22i2014.27. ISSN 2169-4435.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Saleeby, Najeeb (1913). The Moro problem; an academic discussion of the history and solution of the problem of the government of the Moros of the Philippine Islands. P. I. [Press of E. C. McCullough & Company ]. pp. 23, 24, 25.

- ^ https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/philamer/afj2200.0001.001?view=text&seq=17 https://books.google.com/books?id=lEaOgkGazTUC&dq=An%20Acad&source=gbs_book_other_versions https://books.google.com/books?id=JiKToUHvWH4C&q=An%20Acad

- ^ Jumala, Francis C. (2019). "In Fulfilment of the Janji: Some Social Merits of the Tausug Pagkaja". International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. 9 (9): 242–261.

- ^ Ramesh, P.V. (27 March 2022). Twitter https://twitter.com/RameshPV2010/status/1507958222354747395.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Tausug". Bangsamoro Commission for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. 1 August 2025. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ "Tausug Architecture" (PDF). www.ichcap.org. 30 June 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "Artists explore state of Filipino art, culture in the diaspora". usa.inquirer.net. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, Volume 2. University of San Carlos. 1974. pp. 129, 126, 132.

Tausug practice preferential cousin marriage, with no particular preference for patrilateral or matrilateral cousins . The practice is explicitly justified in terms of the ease of the marriage negotiations in an arranged marriage : in ...

- ^ Kiefer, Thomas M. (1969). Tausug Armed Conflict: The Social Organization of Military Activity in a Philippine Moslem Society. Research Series No. 7 Series (reprint ed.). Philippine Studies Program, University of Chicago. pp. 28, 75. ISBN 0598448330.

There is also a tendency towards kindred epdogany, normatively sanctioned through preferential cousin marriage . This preference is Justified by such practical considerations as the ease of the marriage negotiations if the parents of ...

- ^ U.S. Army Special Forces Language Visual Training Materials – TAUSUG. Jeffrey Frank Jones. p. 7.

Traditionally, marriages are arranged to first or second cousins; however, most young adults are now starting to choose their own spouses. In the Tausug society, there is no generally approved method for courting.

- ^ Kiefer, Thomas M. (1986). The Tausug: Violence and Law in a Philippine Moslem Society (illustrated, reprint, reissue, revised ed.). Waveland Press. pp. 40, 44, 81. ISBN 0881332429.

A marriage with a first cousin is considered ideal for several reasons . First, there is the ease of negotiation when the transaction is arranged between the parents ( who would be siblings ) of first cousins .

- ^ an- Naʾīm, ʿAbdallāh Aḥmad, ed. (2002). "1 Social, Cultural and Historical Background :The Region and Its History". Islamic Family Law in a Changing World: A Global Resource Book. Vol. 2 van Global resource book (illustrated ed.). Zed Books. p. 255. ISBN 1842770934.

Among the Tausug communities, marriages are ideally arranged by parents, in line with Islamic law . First and second cousins are favoured spouses since their parents are kinsmen and the problems of inheritance are simplified .

- ^ Kiefer, Thomas M. (1972). Tausug of the Philippines. Descriptive ethnography series Ethnocentrism series, Human Relations Area Files Ethnocentrism series. HRAFlex book OA16-001. Contributor Bijdrager. Human Relations Area Files. pp. 109, 140, 142.

It is not likely for a sister to feed her sister's child as this might interfere with first – cousin marriage . ' Grandparents are very likely to feed . M.2.4.Q : What things would make little boys cry ? Little boys would cry if they ...

- ^ Johnson, Mark (2020). Beauty and Power: Transgendering and Cultural Transformation in the Southern Philippines. Explorations in Anthropology (reprint ed.). Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1000184570.

Technically it is the usba of either side who negotiate the marriage transactions; the woman's father's kindred is ... given the preference of many Tausug and some Sama for first-cousin marriage, incest (sumbang) at once inscribing and ...

- ^ Ethnology, Volume 10. University of Pittsburgh. 1971. pp. 88, 81, 89.

MARRIAGE Tausug marriage involves a complex sequence of activities, of both a ritual and secular nature . ... Marriage Preferences The preferred marriage is between first cousins; the next preference is between second cousins ...

- ^ Hassan, Irene (1975). Tausug-English Dictionary: Kabtangan Iban Maana. Vol. 4 of Sulu studies. Contributors Notre Dame of Jolo College. Coordinated Investigation of Sulu Culture, Philippines. Bureau of Public Schools, Summer Institute of Linguistics. Coordinated Investigation of Sulu Culture. p. 23.

- ^ Madale, Nagasura T. (1981). The Muslim Filipinos: A Book of Readings. Alemar-Phoenix Publishing House. p. 67.

Like most Philippine ethnolinguistic groups, Tausug kinship was bilateral, emphasizing relationships derived from ... There was a tendency toward marriage within the kindred and a marked tendency toward preferential cousin marriage ...

- ^ Espaldon, E. M. (1997). With the Bravest: The Untold Story of the Sulu Freedom Fighters of World War II. Pilipinas: Espaldon-Virata Foundation.

- ^ Alonto, Rowena (2009). 13 Stories of Islamic Leadership vol 1 (PDF). Asian Institute of Management – Team Energy Center for Bridging Societal Divides. p. 26.

- ^ Tobias, Maricris Jan. "GAMABA: Darhata Sawabi". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Abinales, P. N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005). State and Society in the Philippines. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1.

- Donoso, Isaac (2022). "The Qur'an in the Spanish Philippines". In García-Arenal, Mercedes; Wiegers, Gerard (eds.). The Iberian Qur'an: From the Middle Ages to Modern Times. De Gruyter. pp. 499–532. doi:10.1515/9783110778847-019. hdl:10045/139165. ISBN 978-3-11-077884-7.

- Gonda, Jan (1975), Religionen: Handbuch der Orientalistik: Indonesien, Malaysia und die Philippinen unter Einschluss der Kap-Malaien in Südafrika, vol. 2, E.J. Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-04330-5

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000–1800. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 91–95. ISBN 9789888083343.

- Larousse, William (2001), A Local Church Living for Dialogue: Muslim-Christian Relations in Mindanao-Sulu, Philippines : 1965–2000, Editrice Pontificia Università Gregoriana, ISBN 978-88-7652-879-8

- Saleeby, Najeeb Mitry (1908), The History of Sulu, Bureau of Printing

External links

[edit]Tausūg people

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Etymology

Pre-Islamic roots and migrations

The Tausūg people's pre-Islamic roots are tied to the broader Austronesian expansion into Island Southeast Asia, with early human activity in the Sulu Archipelago evidenced by archaeological finds at the Baloboc rock shelter on Sanga-Sanga Island, Tawi-Tawi, dating to approximately 8,000 years ago, indicating initial hunting and foraging societies that transitioned to more sedentary, boat-building communities by around 4,000 years ago.[4] This substrate included Austronesian seafarers arriving via migrations from Taiwan around 5,000 years ago, marked by red-slipped pottery and maritime adaptations that facilitated settlement across the archipelago's islands.[4] Specific Tausūg ethnogenesis occurred through migrations from northeastern Mindanao, particularly descendants of Butuanon and Surigaonon groups from the Rajahnate of Butuan, who moved southward into the Sulu Archipelago around 700 years ago (circa 13th century), blending with indigenous Sama-Bajau populations and other local elements.[4] Linguistic evidence supports this, with the Tausūg language exhibiting ties to Butuanon dialects, reflecting Austronesian Visayan-branch influences amid the archipelago's diverse proto-Sama linguistic milieu.[4] Genetic intermixing among these groups, including maritime creolization between incoming settlers and sea-nomadic Sama, formed the foundational Tausūg identity through economic specialization in coastal resources and intermarriage.[4] Pre-Islamic Tausūg society lacked centralized authority, organizing instead into decentralized banwa (territorial communities) led by datus (chieftains) within bilateral kinship networks extending to second cousins, emphasizing cognatic descent and extended family ties for social cohesion.[4] [5] These groups sustained themselves through kinship-based trade networks exploiting the archipelago's strategic position, involving marine foraging, inter-island exchange of goods like pottery and marine products, and early hierarchical distinctions between aristocrats, commoners, and dependents, without overarching political unification.[4]Name origins and early identity

The ethnonym Tausūg derives from the words tau, meaning "person" or "man," and sūg (or sug), denoting "current" or "sea current," collectively signifying "people of the current." This etymology highlights the group's historical adaptation to the maritime environment of the Sulu Archipelago, where powerful tidal currents shaped navigation, fishing, and trade patterns central to their livelihood.[6][7] Early references to Sulu's inhabitants in external records, such as Chinese accounts from the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), describe trade and tributary interactions without employing the specific term Tausūg or equivalent ethnic identifiers; these sources instead note polities and populations in the region generically as maritime actors engaged in commerce with East Asia. Malay chronicles similarly allude to Sulu as a navigational hub linked to Borneo and the Malay world prior to Islamic consolidation, emphasizing collective seafaring traits over distinct tribal nomenclature. Such pre-modern documentation suggests that early identity was tied to locality and ecological adaptation rather than fixed ethnonyms, with the Tausūg label emerging organically to denote those rooted in the archipelago's currents.[8][9] The broader colonial-era designation "Moro," applied by Spanish authorities to encompass various Muslim populations including the Tausūg, represented an external imposition derived from Iberian encounters with North African Muslims, lacking roots in indigenous self-conception and often carrying pejorative connotations to justify conquest. Tausūg communities historically maintained a separate identity from neighboring Muslim groups like the Maguindanao, rooted in unique linguistic affiliations within the Austronesian family and territorial claims centered on Sulu rather than mainland Mindanao, rejecting subsumption under pan-Moro categorizations that overlooked these variances.[10]Historical Sultanate and Economy

Formation of the Sultanate of Sulu

Islam reached the Sulu Archipelago in the late 14th century via Arab, Persian, and Malay traders navigating key maritime routes between China, the Malay Peninsula, and the Indian Ocean. These merchants, often accompanied by religious scholars, introduced Islamic teachings to local chieftains and communities, fostering conversions among the Tausūg and related groups through peaceful propagation rather than conquest. By approximately 1380, early missionaries such as Tuan Masha'ika had established a foothold, building mosques and promoting monotheism over pre-existing animist practices centered on ancestral spirits and nature worship.[11][12] The transition to formalized Islamic rule accelerated in the early 15th century with the arrival of Raja Baginda, a Sumatran prince who settled in Buansa on Jolo Island and allied with local datus, further embedding Islamic customs in governance and social structures. The sultanate's foundation crystallized around 1450 when Sharif Abu Bakr, an Arab sayyid from Johor with claimed descent from the Prophet Muhammad, arrived from Malacca. He married Paramisuli, daughter of Raja Baginda, leveraging kinship ties and religious authority to mediate disputes among fragmented island polities and proclaim himself Sultan Sharif ul-Hashim. This act unified disparate Tausūg chiefdoms under a single Islamic monarchy, supplanting loose tribal confederacies with hereditary sultanic rule.[13][14][15] Sharif Abu Bakr's consolidation relied on marriage alliances with influential datus and the adoption of Sharia as the legal framework, which provided a cohesive ideology for authority and dispute resolution across the archipelago's islands. This early administration emphasized Islamic principles in taxation, inheritance, and justice, distinguishing the sultanate from neighboring non-Islamic entities and enabling centralized control over approximately 400 islands by mid-century. The shift to sultanate governance thus represented a causal outcome of trade-driven Islamization, where economic connectivity supplied both the faith and the administrative models from Malay-Islamic precedents.[16][8]Maritime trade, piracy, and slave raiding

The Sulu Sultanate's economy from the late 18th to 19th centuries centered on exporting marine and forest products such as pearls, mother-of-pearl shells, edible bird's nests, sea cucumbers (trepang), shark fins, tortoise shells, and beeswax, primarily to Chinese markets via Amoy traders. These goods were bartered for textiles, porcelain, opium, and ironware, with additional exchanges involving Borneo polities and British outposts like Labuan and Singapore, yielding substantial wealth for the Tausūg aristocracy through a barter system that bypassed formal currency. Slave labor was essential for harvesting these commodities, as divers and gatherers were predominantly captives compelled to exploit reefs and islands in the Sulu Archipelago.[17][18][19] Organized piracy and slave raiding, frequently directed by sultanate datus and fleets of Iranun and Samal auxiliaries, complemented trade by supplying labor and plunder, targeting Spanish galleons and coastal settlements in the Visayas, Luzon, and beyond during the Moro Wars (1565–1876). These operations, often state-sanctioned as extensions of warfare and economic strategy, involved fast vinta warships equipped for swift assaults, capturing thousands annually at peak periods in the early 19th century. Historical estimates indicate that from 1770 to 1898, Sulu Zone raiders seized 200,000 to 300,000 individuals, primarily non-Muslim Visayans and coastal dwellers, through ambushes on villages and vessels.[17][20][19] The slave trade reinforced trade interdependence, as captives—valued at 20 to 50 Spanish dollars each—were either retained for production roles in pearl fisheries and nest collection or exported to China and Borneo, funding imports and elevating Tausūg elites via a hierarchy dependent on coerced labor. Integration occurred for some through Islamic conversion and assimilation into households, yet the system's export orientation persisted, with Jolo serving as a major entrepôt handling thousands of slaves yearly by the 1840s. American forces suppressed raiding and slavery post-1899, enforcing prohibitions by 1904 that dismantled the labor base, shifting the economy toward diminished commodity extraction without captives.[21][22][23]Diplomatic relations and territorial extent

The Sultanate of Sulu established tributary relations with the Ming Dynasty of China as early as 1417, when Sultan Paduka Batara led a mission to the imperial court, fostering diplomatic legitimacy through ritual acknowledgment of Chinese superiority while facilitating trade in exotic goods.[9] These ties persisted intermittently into the Qing era, with missions resuming in 1726–1733, though they provided symbolic prestige rather than substantive military assistance against European encroachments.[9] In European diplomacy, Sultan Muhammad Fadl signed a treaty of peace and friendship with James Brooke, representing British interests from Labuan, on 24 January 1848, which recognized Sulu sovereignty over its territories including dependencies in North Borneo while promoting commerce and mutual non-aggression.[8] Similarly, the treaty of 30 April 1851 with Spain compelled Sultan Pulalun to acknowledge Spanish overlordship over Sulu proper and its archipelago in exchange for nominal protection and cessation of hostilities, yet Sulu retained practical autonomy and title to peripheral areas like Balangingi, with interpretations of sovereignty remaining ambiguous and contested.[24] At its zenith in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Sultanate's territorial influence spanned the Sulu Archipelago, Basilan, Tawi-Tawi, and extended suzerainty over northeastern Sabah (North Borneo) through conquests, alliances with local datus, and maritime dominance, though actual administrative control was often nominal beyond core islands.[25] By the late 19th century, internal succession feuds, dynastic fragmentation, and escalating colonial pressures from Spain, Britain, and later the United States eroded this extent, confining effective sway to Jolo and adjacent isles while modern heirs' claims to Sabah—rooted in the 1878 lease agreement rather than outright cession—persist as diplomatic flashpoints despite limited historical enforcement.[25][26]Colonial Encounters and Resistance

Conflicts with Spanish colonizers

The first significant Spanish contact with the Tausūg occurred during Ferdinand Magellan's expedition in 1521, which reached the Sulu Archipelago, though sustained interactions began later with exploratory voyages in the 1560s and 1570s.[8] Escalation to open conflict followed the 1578 expedition led by Captain Esteban Rodríguez de Figueroa under Governor-General Francisco de Sande, targeting Jolo to subdue Sultan Muhammad ul-Halim and impose vassalage; despite initial defeats inflicted on Tausūg forces, the Spanish exacted tribute but failed to occupy the fortified capital, marking the onset of protracted warfare.[27][8] Major invasions intensified in the early 17th century, including failed assaults in 1602 by Juan Juárez Gallinato and 1629 by Lorenzo de Olaso, where Tausūg defenders repelled attackers using hill fortifications, stockades, and ambushes, exploiting Spanish vulnerabilities to disease and supply shortages.[8] The most ambitious campaign came under Governor-General Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera in 1638, deploying 80 vessels and 2,000 troops to besiege Jolo for over three months; Tausūg forces, leveraging stone forts, trenches, artillery, and guerrilla tactics from interior hills, inflicted heavy casualties before evacuating the town, which Spanish forces briefly occupied until withdrawing in 1646 amid unsustainable logistics and renewed raids.[8] Alliances with the Maguindanao Sultanate provided Tausūg reinforcements and coordinated raids on Spanish-held Visayan coasts, further straining colonial resources.[8] Subsequent 18th-century expeditions, such as those in 1737 and repeated Jolo assaults, yielded temporary truces but no conquest, as Tausūg naval mobility outmatched Spanish galleon-based forces limited by monsoon-dependent operations and inadequate sea control.[8] By the early 19th century, mutual exhaustion prompted Spanish subsidies framed as "annual salaries" or peace incentives—such as 6,000 pesos paid to Sultan Alim ud-Din I in 1746 for anti-piracy cooperation and escalating annuities up to the 1850s—to curb Tausūg slave-raiding fleets targeting Christian settlements, effectively functioning as protection payments rather than genuine tribute extraction.[8] These arrangements persisted until renewed offensives in 1848–1851 under Governors Narciso Clavería and Ramón Urbiztondo captured Balangingi strongholds and Jolo, destroying forts and killing hundreds, yet full subjugation eluded Spain due to persistent guerrilla resistance and the archipelago's dispersed geography.[8]American pacification and Moro Wars

Following the Spanish surrender of Jolo on May 20, 1899, U.S. forces under Captain John Bates negotiated the Bates Agreement with Sultan Jamalul Kiram II on August 20, 1899, establishing a temporary truce that recognized American sovereignty while preserving internal Sultanate authority and prohibiting alliances with Filipino insurgents.[28][29] This non-ratified pact aimed to neutralize Tausūg resistance during the Philippine-American War but proved fragile, as incidents of non-compliance, including resistance to disarmament and taxation, escalated tensions.[30] The truce unraveled amid sporadic clashes, culminating in the First Battle of Bud Dajo from March 5 to 8, 1906, where U.S. troops under Major General Leonard Wood assaulted a volcanic crater stronghold on Jolo Island occupied by approximately 800-1,000 Tausūg fighters, women, and children who had refused disarmament and fled taxes.[31] American forces, employing artillery and rifles, incurred 15-21 killed and 70 wounded, while nearly all occupants perished, with no survivors reported among the defenders.[23] This engagement exemplified U.S. tactics of decisive force against fortified holdouts, contrasting Spanish failures through superior firepower and coordination, though it drew domestic criticism for high civilian casualties. Under Brigadier General John J. Pershing's command of the Moro Province from 1909, campaigns intensified, including the Battle of Bud Bagsak in June 1913, where U.S. forces eliminated several thousand Tausūg resisters in another Jolo crater, marking the effective end of organized Moro resistance by mid-1913.[32] Pershing's policies emphasized disarmament, road-building for access, and suppression of juramentado suicide attacks, leveraging modern weaponry like the .45-caliber pistol against edged weapons.[33] Naval patrols and garrisons curtailed Tausūg maritime raiding and slave-taking, which had persisted under Spanish rule, achieving pacification within 14 years through sustained military presence and logistical superiority.[23] Administrative reforms eroded the Sultanate's authority, transitioning from centralized rule under Kiram II—who died in 1936 without formal recognition—to a U.S.-administered civil government in 1914, with appointed datus replacing hereditary leaders to enforce cedula registration and tax compliance.[33] This shift, while reducing endemic violence and integrating Sulu into Philippine administration, dismantled traditional hierarchies, fostering long-term dependency on American oversight rather than indigenous governance revival. Empirical outcomes—near-elimination of piracy by 1913 and cessation of large-scale uprisings—underscore the campaigns' success in imposing order, attributable to technological disparity and strategic focus absent in prior colonial efforts.[23]Japanese occupation and post-WWII transitions