Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Overseas Railroad

View on Wikipedia

Overseas Highway and Railway Bridges | |

| |

| Location | Bridges on U.S. 1 between Long and Conch Key, Knight and Little Duck Key, and Bahia Honda and Spanish Key, Florida Keys, Florida |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 24°42′42″N 81°7′23″W / 24.71167°N 81.12306°W |

| Area | 30.2 acres (12.2 ha) |

| Built | 1905–1912 |

| Architect | Florida East Coast Railway; Overseas Highway & Toll Bridge Comm. |

| Architectural style | Arch, Girder & Truss Spans |

| NRHP reference No. | 79000684[1] |

| Added to NRHP | August 13, 1979 |

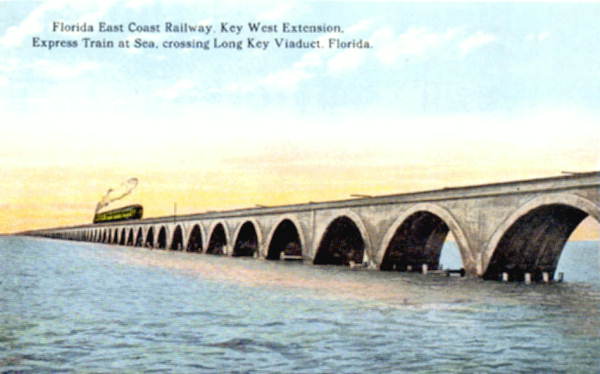

The Overseas Railroad (also known as Florida Overseas Railroad, the Overseas Extension, and Flagler's Folly) was an extension of the Florida East Coast Railway to Key West, a city located 128 miles (206 km) beyond the end of the Florida peninsula. Work on the line started in 1905[2] and it operated from 1912 to 1935, when it was partially destroyed by the Labor Day Hurricane. Some of the remaining infrastructure was used for the Overseas Highway.

Background

[edit]Henry Flagler (1830–1913) was a principal in Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler and later a founder of Standard Oil during the Gilded Age in the United States. The wealthy Flagler took an interest in Florida while seeking a warmer climate for his ailing first wife in the late 1870s. Returning to Florida in 1881, he became the builder and developer of resort hotels and railroads along the east coast of Florida.

Beginning with St. Augustine, he moved progressively south. Flagler helped develop Ormond Beach, Daytona Beach, and Palm Beach, and became known as the father of Miami, Florida.

Flagler's rail network became known as the Florida East Coast Railway (FEC). By 1904, the FEC had reached Homestead, south of Miami.

Key West Extension

[edit]

After the United States announced in 1905 the construction of the Panama Canal, Flagler became particularly interested in linking Key West to the mainland. Key West, the United States' closest deep-water port to the Canal, could not only take advantage of Cuban and Latin American trade, but the opening of the Canal would allow significant trade possibilities with the West Coast.

Initially called "Flagler's Folly", the construction of the Overseas Railroad required many engineering innovations as well as vast amounts of labor and monetary resources. Once the decision was made to move forward with the project, Flagler sent his engineer William J. Krome to survey potential routes for the railroad. The initially favored route extended the railroad from Homestead southwest through the Everglades to Cape Sable, where it would then cross 25 miles (40 km) of open water to Big Pine Key and then continue to Key West. However, it was quickly determined that it was more feasible to run the railroad south to Key Largo and follow the islands of the Florida Keys. Krome then surveyed routes to Key Largo, including one over Card Point (which would become the first roadway to the Keys) and Jewfish Creek, which was the selected route.[3]

At one time during construction, four thousand men were employed. During the seven year construction, three hurricanes—one in 1906, 1909, and 1910—threatened to halt the project. The project cost was more than $50 million.

Despite the hardships, the final link of the Florida East Coast Railway to Trumbo Point in Key West was completed in 1912. In this year, a proud Henry Flagler rode the first train into Key West aboard his private railcar, marking the completion of the railroad's oversea connection to Key West and the linkage by railway of the entire east coast of Florida. It was widely known as the "Eighth Wonder of the World".[4]

Operations

[edit]

During its years of operation, freight traffic volume on the single-track overseas extension was disappointing, as the anticipated growth in Panama Canal cargo shipping through Key West failed to materialize. Local Key West and online freight consisted of coal, fruit, and building materials. Trains of tank cars brought potable water to Key West from mainland Florida.

Before the Great Depression hit, passenger traffic consisted of both local and long distance trains. In 1929, the Havana Special was the premier train, providing year-round coach and sleeping car service between New York and Key West, daily except Sundays, with connecting ferry service beyond to the Cuban capital. With speed restricted to 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) on the long bridges, it took a leisurely four and a half hours to travel the distance between Key West and Miami: northbound, the Havana Special departed Key West at 6 p.m., for a 10:45 p.m. departure from Miami.[5] Another train, the Over-Sea, operated locally between Miami and Key West during daylight hours, leaving Miami at 11:05 a.m. and arriving at Key West 4:35 p.m.[6] During the winter months, the Over-Sea's consist included a deluxe parlor-observation car. It was a popular train for vacationers traveling to the various fishing camps in the Keys. The Caribbean Mail also operated over the line.

Demise

[edit]Much of the Overseas Railroad in the Middle Keys was heavily damaged and partially destroyed in the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935, a Category 5 hurricane which is often called "The Storm of the Century". The storm killed more than 400 people and devastated Long Key and adjacent areas. The FEC's Long Key Fishing Camp was destroyed, as was an FEC rescue train which, with the exception of steam locomotive 447, was overturned by the storm surge at Islamorada. Over 40 miles (64 km) of track were washed away by the hurricane, two miles of which ended up washing ashore on the mainland at Cape Sable.[3]

Already bankrupt, the Florida East Coast Railway was financially unable to rebuild the destroyed sections. The roadbed and remaining bridges were sold to the State of Florida, which built the Overseas Highway to Key West, using much of the remaining railway infrastructure. Many of the original bridges were replaced during the 1980s. The Overseas Highway (U.S. 1, which runs from Key West to Fort Kent, Maine) continues to provide a highway link to Key West. Many old concrete bridges of the Overseas Railroad remain in use as fishing piers and pedestrian paths called the Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail.[7]

It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 as Overseas Highway and Railway Bridges.

Gallery

[edit]-

Florida ECR train in 1912

-

Florida ECR train in a storm in 1912

-

Florida ECR train in 1928

-

Henry Flagler's train with his private car "Rambler" returning from Key West, Florida on the Overseas Railroad

-

Overseas Railroad bridge west of Bahia Honda Key, 2006. The bridge has been severed to prevent pedestrian access.

-

Florida Overseas Railroad map, 1915

-

Arrival of the first train at Key West, January 22, 1912.

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Born GW (2003)Historic Florida Keys: an illustrated history of Key West & the Keys, HPN Books P47

- ^ a b Hopkins, Alice. "The Development of the Overseas Highway" (PDF). FIU Digital Collections. Florida International University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Standiford, Les (2002). Last Train to Paradise. Broadway Paperbacks. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4000-4947-9.

- ^ "Faster Trains Miami-New York Is F.E.C. Plan". Miami Daily News. May 1, 1929. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "F.E.C. ready to start its fast service". Fort Lauderdale News. November 22, 1929. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail". Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Speedway to Sunshine: The Story of the Florida East Coast Railway. Bramson, Seth H. Boston Mills Press, Erin, ONT. 2002 [ISBN missing]

- Standiford, Les (2002). Last Train to Paradise. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-609-60748-0.

- Bethel, Rodman J. (1987). Flagler's Folly: The Railroad That Went to Sea and Was Blown Away. Slumbering Giant Pub Co. ISBN 0961470224, 978-0961470227

- Chapple, Joe Mitichell (January 1906). "A Railroad Over the Ocean Surf". National Magazine.

- Heppenheimer, T.A. (2004) "The Railroad That Went to Sea". American Heritage. Winter, 2004. Found at [1]

- Parks, Pat and Corcoran, Tom (2010).The Railroad That Died at Sea: The Florida East Coast's Key West Extension, Revised Edition. Ketch & Yawl LLC. ISBN 0978894995, 978-0978894993

External links

[edit]- Henry Flagler – Builder of the Overseas Railway | Key West Art & Historical Society

- Florida East Coast Railway – Overseas Extension Collection | Key West Art & Historical Society