Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Marquesas Keys

View on Wikipedia

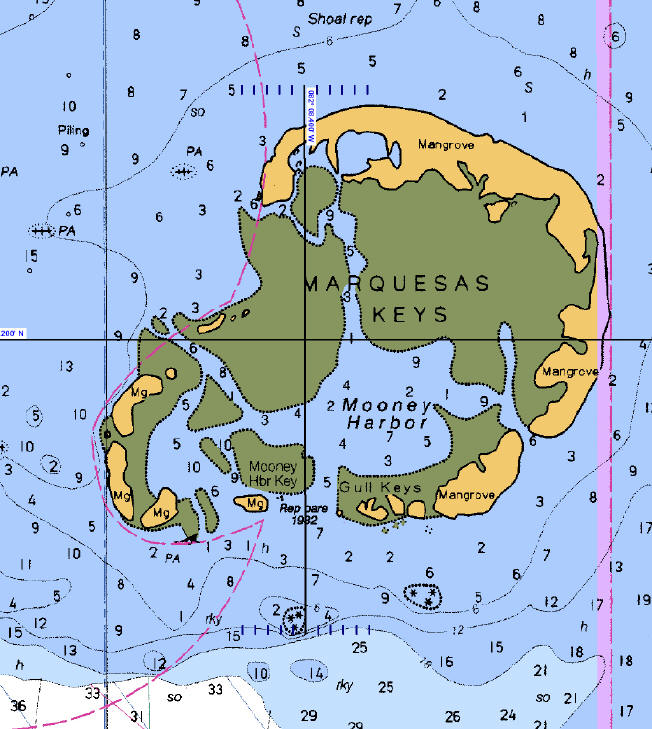

The Marquesas Keys form an uninhabited island group about 20 miles (32 km) west of Key West, four miles (6 km) in diameter, and largely covered by mangrove forest. They are an unincorporated area of Monroe County, Florida and belong to the Lower Keys Census County Division.[1] They are protected as part of the Key West National Wildlife Refuge.[2] The Marquesas were used for target practice by the military as recently as 1980.

Key Information

Overview

[edit]The total area, including the lagoon, measures 29.37 km2 (11.34 sq mi). The land area, according to the United States Census Bureau, is 6.58 km2 (2.54 sq mi) (exactly 6,579,703 m2), the water area 0.17 km2 (0.066 sq mi) (165,744 m2), giving a combined area of 6.75 km2 (2.61 sq mi), not counting water areas with connection to the open sea, but including small landlocked lakes on the Keys. The group is located at coordinates 24°34′19″N 82°07′10″W / 24.57194°N 82.11944°W.

The islands are part of the Florida Keys, separated from the rest of the Florida Keys, which are farther east, by the Boca Grande Channel, which is 6 miles (9.7 km) wide until Boca Grande Key, the westernmost of the Mule Keys. Only the Dry Tortugas are farther west, 36 miles (58 km) west of the Marquesas Keys.

The central lagoon is called Mooney Harbor. The northernmost key is the largest and has a strip of sandy beach free of mangrove. In the past it was known as "Entrance Key". It surrounds the lagoon in the north and east. Adjoining in the south are smaller keys such as Gull Keys, Mooney Harbor Key, and finally about four unnamed keys in the southwest corner of the group. Older charts show that two of these keys once were named "Button Island" and "Round Island".[3]

Six miles (10 km) west of the Marquesas Keys is Rebecca Shoal.

While the islands are uninhabited by humans, rays, sharks, sea turtles, and bird life abound. The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary has designated no-motor and no-access areas to protect nesting, feeding, and roosting birds and nesting turtles.[4]

The islands are also known for sport fishing.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Marquesas Keys: Blocks 3042 and 3043, Census Tract 9725, Monroe County, Florida United States Census Bureau

- ^ NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Maps, Florida Keys West

- ^ "Marquesas Keys". keys.FIU.edu. December 11, 2006. Archived from the original on December 11, 2006.

- ^ "Marquesas Keys Wildlife Management Area". Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. NOAA. Retrieved 4 January 2023.