Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Florida Reef

View on Wikipedia

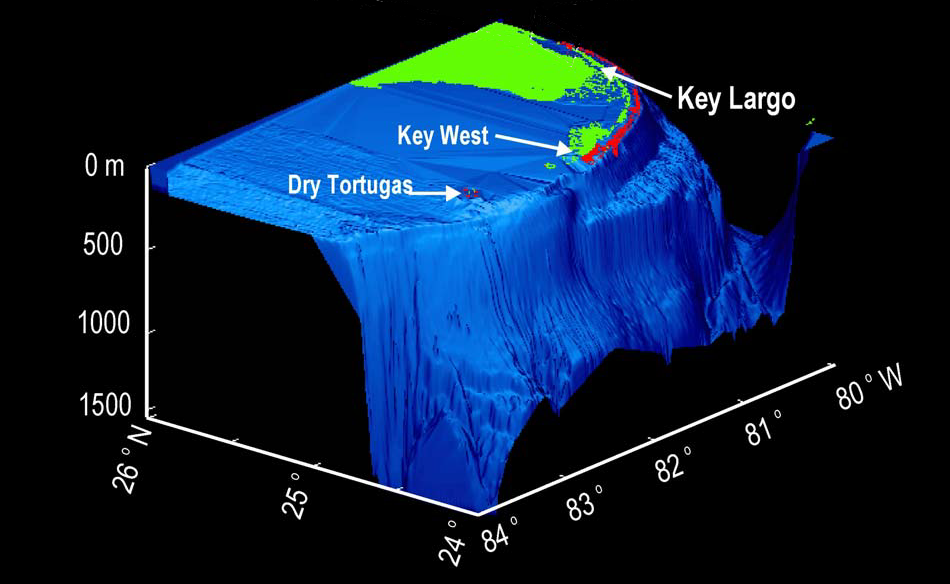

The Florida Reef (also known as the Great Florida Reef, Florida reefs, Florida Reef Tract and Florida Keys Reef Tract) is the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States.[1] It lies a few miles seaward of the Florida Keys, is about 4 miles (6 to 7 km) wide and extends along the 20-metre (66 ft) depth contour 270 km (146 nmi; 168 mi) from Fowey Rocks just east of Soldier Key to just south of the Marquesas Keys. The system encompasses more than 6,000 individual reefs. Florida waters are home to over 500 marine fish and mammal species along with more than 45 species of stony corals and 35 species of octocorals.[2]

Geography

[edit]The barrier reef tract forms a great arc, concentric with the Florida Keys, with the northern end, in Biscayne National Park, oriented north-south and the western end, south of the Marquesas Keys, oriented east-west. The rest of the reef outside Biscayne National Park lies within John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Isolated coral patch reefs occur northward from Biscayne National Park as far north as Stuart, in Martin County. In 2024, Florida created the Kristin Jacob Coral Aquatic Preserve to protect the reefs north of Biscayne National Park.[3] Coral reefs are also found in Dry Tortugas National Park west of the Marquesas Keys. The reefs are 5,000 to 7,000 years old, having developed since sea levels rose following the Wisconsinan glaciation.[4]

The densest and most spectacular reefs, along with the highest water clarity, are found to the seaward of Key Largo (in and beyond John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park) and Elliott Key (the northernmost 'true' Florida Key) where the two long keys help protect the reefs from the effects of water exchange with Florida Bay, Biscayne Bay, Card Sound and Barnes Sound. The bays and sounds (all between the Florida Keys and the mainland) tend to have lower salinity, higher turbidity and wider temperature variations than the water in the open ocean. Channels between the Keys allow brackish water from the bays to flow onto the reefs (especially in the middle Keys), limiting their growth.[5] Microstructural abnormalities in large benthic foraminifera from the Florida Keys indicate carbonate chemistry stress that is also consistent with long-term environmental decline on the reef tract[6] A 2024 study found that the best habitat for Acropora palmata restoration occurs in areas with low chlorophyll‑a levels, moderate wave exposure, and stable salinity, including Biscayne Bay, the Upper Keys, western‑lower Keys, and Dry Tortugas, while conditions in the middle Keys are generally less suitable.[7]

Reef structure and communities

[edit]The Florida Reef consists of two ridges separated from the Florida Keys by the Hawk Channel. Closest to the Keys is a sand ridge called White Bank, covered by large beds of sea grass, with patch reefs scattered across it. Further out to sea on the edge of the Florida Straits is the second ridge forming the outer reefs, covered by reefs and hard banks composed of coral rubble and sand.[8]

Almost 1,400 species of marine plants and animals, including more than 40 species of stony corals and 500 species of fish, live on the Florida Reef. The Florida Reef lies close to the northern limit for tropical corals, but the species diversity on the reef is comparable to that of reef systems in the Caribbean Sea.[8]

The Florida Museum of Natural History defines three communities on the Florida reefs. The hardbottom community lies closest to the Florida Keys and consists primarily of algae, sea fans (gorgonians) and stony corals growing on limestone rock that has a thin covering of sand. The stony corals in hardbottom communities include smooth starlet coral (Siderastrea radians), mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides), golfball coral (Favia fragum), elliptical star coral (Dichocoenia stokesii) and common brain coral (Diploria strigosa). Hardbottom provides habitat for anemones, mollusks, crabs, spiny lobsters, seastars, sea cucumbers, tunicates and various fish, including grunts (Haemulon spp.), snappers (Lutjanus spp.), groupers (Epinephelus spp.), Atlantic blue tang (Acanthurus coeruleus), Ocean surgeon (Acanthurus bahianus) and Great barracuda (Spyraena barracuda).[9]

Second is the patch reef community. Patch reefs form in shallow water (three to six meters deep), some in Hawk Channel and some on the outer reef, but mainly on White Bank between Hawk Channel and the outer reefs. Patch reefs start from corals growing on a hard bottom, but grow upward as new corals establish themselves on the skeletons of dead corals. Most of the structure of patch reefs is formed from star (Montastraea annularis, Siderastrea siderea) and brain corals (Diploria spp.). Other corals attach wherever there is an opening. Patch reefs may grow up to the surface of the water, and spread outwards. Dome-type patch reefs (such as Hen and Chickens), found in Hawk Channel and on White Bank, are round or elliptical, and are generally less than three meters high, but may reach up to nine meters high. Dome-type patch reefs are surrounded by sand which is kept clear due to browsing by long-spined sea urchins and grass-eating fish. Linear-type patch reefs are found on the outer reefs, and are linear or curved. They occur in single or multiple rows, trending the same direction as the bank reefs on the outer reefs. Linear-type patch reefs often include elkhorn coral, which is rare on the dome-type patch reefs. As dead coral skeletons age and are weakened by the activities of boring sponges, worms, and mollusks and by wave action, parts of a patch reef may collapse. Patch reefs provide habitat for spiny lobsters and for many species of fish, including Bluehead wrasse (Thalassoma bifasciatum), damselfish (Chromis spp.), Ocean surgeon, French and queen angelfish (Pomacanthus spp.), white, caesar and spanish grunts (Haemulon ssp.), yellowtail and other snappers, redband and stoplight parrotfish (Sparisoma ssp.), sergeant major (Abudefduf saxatilis), tomtate (Haemulon aurolineatum), trumpetfish (Aulostomus maculatus), filefish, groupers, snappers, bar jack (Caranx ruber), great barracuda, pufferfish, squirrelfish, cardinalfish, and green morays (Gymnothorax funebris).[10]

Third is the bank reef community. Bank reefs are larger than patch reefs and are found on the outer reefs. Bank reefs consist of three zones. The reef flat is closest to the keys, and consists of coralline algae growing on fragments of coral skeletons. Further out to sea are the spur and groove formations, low ridges of coral (the spurs) separated by channels with sand bottoms (the grooves). The shallowest parts of the spurs support fire corals and zoanthids. Starting at five or six feet deep, Elkhorn, star, and brain corals are the most important members of the community. Various types of gorgonians are also common. Beyond the spur and groove zone is the forereef, which slopes down to the deeps. The upper forereef is dominated by star coral. At greater depths plate-like corals dominate, and then as the available light fades, sponges and non-reef building corals become common. Bank reefs provide habitat for various fishes, including French angelfish, blue and queen parrotfish, Queen triggerfish (Balistes vetula), rock beauties (Holacanthus tricolor), Goatfish (Parupeneus cyclostomus), porkfish (Anisotremus virginicus) and snappers. The sand found around and in the Florida Reef is composed of shell, coral skeleton and limestone fragments.[11]

In 2025, large‑scale planting of nursery‑grown corals began in the Florida Keys, aiming to expand restoration.These efforts involve growing corals in protected nursery environments until they are strong enough to be transplanted into degraded reef areas.[12] Sediment analyses over time show a shift on the Florida Reef Tract, with coral debris tripling in the Middle Keys over a 37-year period, indicating major changes in reef framework production.[13]

Other common species of hard coral found on the Florida Reef include Ivory Bush Coral (Oculina diffusa), which is the dominant coral in the patch reefs along the Florida coast north of the Florida Keys, staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis), lettuce coral (Agaricia agaricites), grooved brain coral (Diploria labyrinthiformis), boulder star coral (Monstastrea annularis), great star coral (M. cavernosa), clubbed finger coral (Porites porites) and massive starlet coral (Siderastrea siderea).[14]

Individual reefs

[edit]Notable individual reefs in the Florida reef system include:

- 9-foot Stake (reef)

- Alligator Reef

- Ajax Reef

- Carysfort Reef

- Cheeca Rocks (reef)

- Coffins Patch (reef)

- Conch Reef

- Crocker Reef

- Davis Reef

- Dry Rocks (reef)

- Eastern Dry Rocks (reef)

- Eastern Sambo (reef)

- French Reef

- Grecian Rocks (reef)

- Hen and Chickens (reef)

- Looe Key

- Marker 32 (reef)

- Molasses Reef

- Newfound Harbor Key (reef)

- Pacific Reef

- Pickles Reef

- Rock Key (reef)

- Sand Key (reef)

- Snapper Ledge (reef)

- Sombrero Key

- Tennessee Reef

- The Elbow (reef)

- Turtle Reef

- Western Sambo (reef)

Threats to the reefs

[edit]

Coral reefs are among the most biologically diverse ecosystems on the planet, supporting approximately 4,000 species of fish and 800 species of hard coral per unit area, more than any other marine habitat. Their ongoing global decline affects ecological balance, as well as the social, cultural, and economic health of human communities. In Florida, coral reefs face several stressors, including overfishing, disease, rapid coastal development, and climate change.[15] As of the late 2010s, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimated that only about 2% of Florida's original coral cover remained, following decades of cumulative stress from pollution, overfishing, disease, and climate change.[16] Animals known as polyps, which create the fundamental structure of a reef, die from ingesting tiny bits of trash floating throughout the ocean called microplastics. Overfishing is also threatening reef fish populations, which feed on the algae that will smother corals. Fluctuating ocean temperatures caused by global warming presents the largest threat to coral reefs.The sudden warming or cooling of the water stresses the corals, causing them to lose their nutrients and turn white, a process known as bleaching. With the destruction of these complex yet fragile ecosystems comes a wide range of global consequences such as extinction of marine species, endangerment to the fishing industries, and severe coastal erosion. Elevated nutrient enrichment and altered freshwater inputs, particularly from historical water-management practices affecting Florida Bay, have contributed to algal overgrowth and declining coral health on the Florida Reef Tract.[17]

In common with coral reefs throughout the Caribbean and the world, the Florida Reef exhibits some signs of stress and deterioration. Precht and Miller state that the numbers of Elkhorn and Staghorn corals (Acropora ssp.) are declining to an extent that is unprecedented in several thousand years. Between 1981 and 1986, Staghorn corals declined by 96% at Molasses Reef. Between 1983 and 2000 at Looe Key, Elkhorn corals declined by 93% and Staghorn corals by 98%. A joint reef monitoring program conducted by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Florida Marine Research Institute and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recorded a loss of 6% to 10% living corals at 40 sampling stations from 1996 to 2000.[18] Long-term monitoring of Florida's coral reefs has shown that stony coral recovery has been minimal in many regions, with some areas exhibiting no measurable regrowth for over 15 years due to repeated disturbances and chronic stressors.[19]

Elevated temperatures can damage coral reefs, causing coral bleaching. The first recorded bleaching incident on the Florida Reef was in 1973. Incidents of bleaching have become more frequent in recent decades, in correlation with a rise in sea surface temperatures. In July 2023, recordbreaking early and rapid warming resulted in widespread coral bleaching and death.[20] Rescue efforts, such as relocating corals to tanks or to deeper waters have helped some bleached corals recover. Oceanographer Jamison Grove at the NOAA stated that these efforts must be accompanied by reductions in greenhouse gas emission to save the reef.[21] The Florida Aquarium and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission have tested a protective device known as the "Coral Defender", which shields young corals from predatory fish and invertebrates. Early trials suggest that the device can significantly improve survival rates for nursery‑reared corals once they are placed in existing reefs.[22] White band disease has also adversely affected corals on the Florida Reef.[23] While hurricanes often can cause localized damage to Elkhorn and Staghorn corals, Precht and Miller state that the severe and widespread loss of those corals on the Florida Reef cannot be attributed to hurricane damage. In addition to coral loss, the degradation of Florida's reefs has led to the flattening of reef structures and a decline in fish populations, particularly in areas near intense coastal development, as the loss of habitat affects reef fish that rely on coral for food, shelter, and reproduction.[24] Other possible causes of the losses of corals on the Florida Reef include epizootic diseases, eutrophication, predation, sedimentation, overfishing, ship groundings, anchor dragging, commercial lobster and crab traps moved by storms, pollution, development on the Keys, growing numbers of visitors to the Keys and the reefs and the growth of seaweed on the coral.[25] In January 2010, the Florida Reef Tract experienced an extreme cold-water anomaly in which temperatures fell below 16 degrees C, which resulted in greater coral tissue morality than prior years.[26] In recent years, considerable effort has been made to make corals resilient to rising temperatures. Researchers from the Florida Aquarium and the University of South Florida are collaborating on a new initiative to protect the Florida Keys' coral reefs. More than 1,000 juvenile elkhorn corals that have been genetically modified to resist environmental stress are being planted at seven locations in the Florida Keys. Before being planted, they are housed in specialized tanks to acclimate to the ocean's temperature. Only a few percentage may survive, but those that do can develop further in the future, according to Cindy Lewis, director of the Keys Marine Laboratory.[27] NOAA's Mission: Iconic Reefs, aims to restore approximately three million square feet of coral habitat across seven key reef sites in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by the year 2040. The project includes large‑scale coral planting, removal of harmful algae, and long‑term monitoring to ensure restored areas continue to thrive in the future.[28]

The long-spined sea urchin (Diadema antillarum), which browses on seaweed on and around reefs, was sharply reduced in numbers on the Florida Reef (and throughout the Caribbean) in the 1980s. While populations of this sea urchin have somewhat recovered elsewhere, its numbers are still very low on most of the Florida Reef, with the exception of the Dry Tortugas. As a consequence, there has been no effective check of the growth of seaweed on reef corals. However, the severe die-off of Elkhorn and Staghorn corals occurred before the die-off of the sea urchins, so that the proliferation of seaweed following the loss of the sea urchins was not the cause of the die-off of the corals, but may be retarding recovery by the corals.[29]

Researchers studying Florida's coral reefs have found that juvenile coral populations remain low even in areas where conditions appear suitable for growth. A major factor contributing to this is the widespread presence of thick, sandy algae mats (referred to as LSAT), particularly in flat reef zones. These mats trap sand and form dense layers that make it difficult for young corals to attach and survive. Although fish that feed on algae are abundant and usually help maintain reef health by controlling harmful algae, they cannot remove the LSAT because the underlying silt blocks light and reduces oxygen levels, creating unfavorable conditions for coral larvae to settle. Furthermore, only certain algae species, such as crustose coralline algae (CCA), support coral recruitment, but these beneficial algae are scarce in these degraded reefs. Other algae types, like Dictyota, do not aid coral growth and may even hinder it.[30] Recent ecological surveys show that following major disturbances, juvenile coral assemblages on the Florida Reef Tract exhibit a shift toward higher octocoral recruitment relative to stony corals.[31] Studies of reef-building corals have shown that bacterial communities in Montastraea annularis can vary significantly across small spatial scales, which suggests complex microbial drivers of coral health and stress response[32] Research in 2024 identified specific environmental factors that predict where Coral restoration is most likely to succeed. Applying these findings can help conservationists focus their efforts on areas with conditions most favorable for coral growth in turn, improving restoration success rates[7]

Another threat to the Florida Reef is the ongoing rise in sea level. The sea level has risen almost six inches (15 cm) at Key West since 1913, and one foot (30 cm) since 1850. This rise in sea level increases the volume of water in Florida Bay significantly, and increases the exchange of water between the Bay and the water over the reefs. The lower salinity, higher turbidity and more variable temperature of the water from Florida Bay adversely affects the reefs. A continued rise in sea level would likely intensify the effect.[33]

A perceived deterioration of the reefs became a concern in the 1950s. Early attempts to protect the reefs led to the establishment in 1960 of a protected area that became John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park. The creation of Biscayne National Monument (which later became Biscayne National Park) in 1968 protected the northern part of the Florida Reef. In 1990 the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary was established, bringing all of the Florida reef into federal or state protection.[34]

Coral reproduction on the Florida Reef has drastically declined, with many species failing to produce new offspring in the wild due to low population density, disease, and environmental stress.[35]

Human use

[edit]Human use of the reefs has grown tremendously in the past century. One measure of the growth is that registrations for recreational boats in Monroe County increased by 1000% from 1964 to 2006.[36]

Recreational use of the Florida Reef and surrounding waters is popular and important to the economy of southern Florida, and in particular, of Monroe County. In 2000-2001 artificial and natural reefs in South Florida[37] and Monroe County had 28 million person-days of recreational use by residents and tourists, including scuba diving, fishing and viewing (as, for example, by snorkeling). These activities generated $4.4 million in sales, generated almost $2 million in local income and provided more than 70,000 full- and part-time jobs. The estimated asset value of the reefs was $8.5 billion. About two-thirds of the activity was related to natural reefs.[38]

In Monroe County for the period of June 2000 to May 2001 almost 5.5 million person-days of reef related activities resulted in $504 million in sales, which generated $140 million in income for 10,000 full- and part-time jobs. Almost two-thirds of the activity was by residents, and about half the activity involved fishing, with one-third involving snorkeling and one-sixth scuba diving. [39]

In Dade County for the period from June 2000 to May 2001 a little over 6 million person-days of reef related activities resulted in $1,297 million in sales, which generated $614 million in income for 19,000 full- and part-time jobs. The activity was about evenly split between residents and tourists. As in Monroe County, about half the activity involved fishing, with one-third involving snorkeling and one-sixth scuba diving.[40]

In a more general sense, the reef acts as a layer of protection for human settlements against tropical storms, hurricanes, and erosion.[21]

Shipwrecks and lighthouses

[edit]The Florida Current (which merges with the Antilles Current near the northern end of the barrier reef to form the Gulf Stream) passes close to the Florida Reef through the Straits of Florida. Ships began wrecking along the Florida Reef almost as soon as Europeans reached the New World. From early in the 16th century Spanish ships returning from the New World to Spain sailed from Havana to catch the Gulf Stream, which meant they passed close to the Florida Reef, with some wrecking on the reefs. In 1622, six ships of the Spanish treasure fleet, including the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, wrecked during a hurricane in the lower Keys. In 1733, 19 ships of the Spanish treasure fleet wrecked during a hurricane in the middle and upper keys. In the 19th century the Straits became the major route for shipping between the eastern coast of the United States and ports in the Gulf of Mexico and the western Caribbean Sea. The combination of heavy shipping and a powerful current flowing close to dangerous reefs made the Florida Reef the site of many wrecks. By the middle of the 19th century, ships were wrecking on the Florida Reef at the rate of almost once a week (the collector of customs in Key West reported a rate of 48 wrecks a year in 1848).[41] Between 1848 and 1859 at least 618 ships were wrecked on the Florida Reef.[42] The Assistant United States Coast Surveyor reported that in the period from 1845 through 1849 almost one million (United States) dollars' worth of vessels and cargos were lost on the reef.[43] The chief motivation for the Florida Railroad, the first railroad to connect the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida, was to allow goods to be transferred between ships in the Atlantic and in the Gulf of Mexico, thus avoiding the dangerous passage along the Florida Reef. Salvaging wrecks on the reefs was the principal occupation in the Florida Keys through much of the 19th century, helping make Key West the biggest and richest city in Florida for a while.[44]

Some of the reefs in the Florida Reef are named after ships that wrecked on them. Fowey Rocks is named after HMS Fowey, which, however, actually wrecked on Ajax Reef. Looe Key is named after HMS Looe. Alligator Reef is named after the USS Alligator.[45] Carysfort Reef is named after HMS Carysfort, which ran aground on the reef, but did not sink.[46]

Soon after the United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1821, it began building lighthouses along the Florida coast. The first lighthouses marking the Florida Reef were the Cape Florida Light, at the northern end of the Reef, the Dry Tortugas Light (on Bush Key), marking the western end of the Reef, and the Key West Light, all first lit in 1825. A light ship was placed at Carysfort Reef in 1825, as well. Garden Key Light, also in the Dry Tortugas, was added in 1826, and Sand Key Light (six nautical miles from Key West), was added in 1827. Large stretches of the Florida Reef remained unprotected by lighthouses, however. Keeping lights in operation along the Florida Reef proved difficult. The Carysfort Reef light ship was often blown out of position, and one time even onto a reef. The first light ship had to be replaced after just five years due to dry rot. The Cape Florida lighthouse was burned by Seminoles in 1836, and was not repaired and re-lit until 1847. The Key West and Sand Key lighthouses were destroyed by a hurricane in 1846. Starting at Carysfort Reef in 1852, skeletal tower lighthouses were built on submerged reefs to place lights as close to the outer edge of the Florida Reef as possible. With the completion of the American Shoal Light in 1880 there were finally navigation lights visible along the full length of the Florida Reef.[47]

In order to provide better charts for ships sailing along the Florida Reef, the Florida Keys, including the reef, and the waters to the west of the Keys, including Biscayne Bay and Florida Bay, were surveyed in the 1850s. The United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers established a base camp on Key Biscayne in 1849. The triangulation survey was conducted by the United States Coast Survey with men detailed from the United States Army and United States Navy. In 1855 Alexander Dallas Bache, Superintendent of the U.S. Coast Survey, assumed personal direction of the survey. In 1851 the U.S. Coast Survey sent Louis Agassiz to study the Florida Reef.[48] His report on the reefs was published in 1880.[49]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The biggest coral reef in the continental U.S. is dissolving into the ocean Accessed May 6, 2016

- ^ "Florida's Coral Reef | Florida Department of Environmental Protection". floridadep.gov. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ "Kristin Jacobs Coral Aquatic Preserve". Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ^ Florida's Coral Reefs Florida Department of Environmental Protection Archived 2011-02-28 at the Wayback Machine Accessed December 14, 2010.

Florida Keys Conservation: National Marine Sanctuary Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History Archived 2010-11-23 at the Wayback Machine Accessed December 14, 2010

Precht and Miller:243

Marszalek et alia:224 - ^ U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1134 - Florida Reef Tract Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine Accessed December 16, 2010

Precht and Miller:243

Marszalek et alia:228 - ^ Crevison, Heidi; Hallock, Pamela; Muller, Pamela Hallock (2007-07-01). "Anomalous Features Observed on Tests of Live Archaiasine Foraminifers from the Florida Keys, USA". Journal of Foraminiferal Research. 37. doi:10.2113/gsjfr.37.3.223.

- ^ a b Banister, Raymond B.; Viehman, T. Shay; Schopmeyer, Stephanie; Woesik, Robert van (2024-01-02). "Environmental predictors for the restoration of a critically endangered coral, Acropora palmata, along the Florida reef tract". PLOS ONE. 19 (1) e0296485. Bibcode:2024PLoSO..1996485B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0296485. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 10760844. PMID 38166125.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1134 - Florida Reef Tract Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine Accessed December 16, 2010

- ^ Hardbottom Community Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History Accessed December 15, 2010

- ^ Patch Reef Community Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History Accessed December 15, 2010

Marszalek et alia:224, 227 - ^ Bank Reef Community Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History Accessed December 15, 2010

- ^ Luscombe, Richard (2025-05-24). "Scientists seek to save Florida's dying reefs with hardy nursery-grown coral". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2025-08-06.

- ^ Lidz, Barbara H.; Hallock, Pamela; Muller, Pamela Hallock (2000-07-01). "Sedimentary Petrology of a Declining Reef Ecosystem, Florida Reef Tract (U.S.A.)". Journal of Coastal Research. 16.

- ^ Common Corals of Florida Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History Accessed December 15, 2010

Coral Reefs Geographical Distribution Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History Accessed December 15, 2010 - ^ "GovInfo". www.govinfo.gov. Retrieved 2025-08-05.

- ^ "'Dire outlook': scientists say Florida reefs have lost nearly 98% of coral; While overall US coral reefs are in fair condition, along the coast of Florida as little as 2% of original coral cover remains. - Document - Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints". go.gale.com. Retrieved 2025-08-05.

- ^ Lapointe, Brian E.; Brewton, Rachel A.; Herren, Laura W.; Porter, James W.; Hu, Chuanmin; Cannizzaro, Jen (2020-04-01). "Sound Science, not Politics, must Inform Restoration of Florida Bay and the Coral Reefs of the Florida Keys". Marine Biology. 167. doi:10.1007/s00227-020-3669-z.

- ^ Precht and Miller:241, 246, 267

- ^ Jones, Nicholas P.; Ruzicka, Rob R.; Colella, Mike A.; Pratchett, Morgan S.; Gilliam, David S. (2022-12-01). "Frequent disturbances and chronic pressures constrain stony coral recovery on Florida's Coral Reef". Coral Reefs. 41 (6): 1665–1679. doi:10.1007/s00338-022-02313-z. ISSN 1432-0975.

- ^ Lindsey, Rebecca (July 28, 2023). "NOAA and partners race to rescue remaining Florida corals from historic ocean heat wave". Climate.Gov. Archived from the original on August 1, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Kozin, Daniel; Lee, Wilfredo; Frisaro, Freida (August 9, 2023). "High ocean temperatures are harming the Florida coral reef. Rescue crews are racing to help". AP News. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ News, Gulf Coast (2025-03-20). "New biodegradable tool deployed in Florida Keys to protect coral restoration". WBBH. Retrieved 2025-08-06.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "The Disease Threatening Coral Reefs In Martin County". Stuart Magazine. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ^ Zuercher, Rachel; Kochan, David P.; Brumbaugh, Robert D.; Freeman, Kathleen; Layko, Rachel; Harborne, Alastair R. (2023). "Identifying correlates of coral-reef fish biomass on Florida's Coral Reef to assess potential management actions". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 33 (3): 246–263. Bibcode:2023ACMFE..33..246Z. doi:10.1002/aqc.3921. ISSN 1099-0755.

- ^ Precht and Miller:243-44, 245, 247-48, 249

The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Florida Keys Accessed December 17, 2010 - ^ Muller-Karger, Frank; Barnes, Brian; Rueda, Digna (2011-01-01). "Severe 2010 Cold-Water Event Caused Unprecedented Mortality to Corals of the Florida Reef Tract and Reversed Previous Survivorship Patterns". PLOS ONE. 6 (8) e23047. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623047L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023047. PMC 3154280.

- ^ "Scientists seek to save Florida's dying reefs with hardy nursery-grown coral; Reefs off the Keys have lost 90% of healthy coral cover in 40 years, but replanting effort aims to make reef more resilient". The Guardian (London, England): NA. 2025-05-24.

- ^ Fisheries, NOAA (2025-06-04). "Restoring Seven Iconic Reefs: A Mission to Recover the Coral Reefs of the Florida Keys | NOAA Fisheries". NOAA. Retrieved 2025-08-06.

- ^ Large-scale surveys on the Florida Reef Tract indicate poor recovery of the long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum Accessed December 17, 2010

Precht and Miller:249

The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Florida Keys Accessed December 17, 2010 - ^ Duran, A.; Speare, K. E.; Fuchs, C.; Adam, T. C.; Palma, L.; Miller, M. W.; Collado-Vides, L.; Harborne, A. R.; Burkepile, D. E. (2024-08-01). "Long sediment-laden algal turf likely impairs coral recovery on Florida's coral reefs". Coral Reefs. 43 (4): 1109–1120. Bibcode:2024CorRe..43.1109D. doi:10.1007/s00338-024-02532-6. ISSN 1432-0975.

- ^ Bartlett, Lucy A.; Brinkhuis, Vanessa I. P.; Ruzicka, Rob R.; Colella, Michael A.; Lunz, Kathleen S.; Leone, Erin H.; Hallock, Pamela; Muller, Pamela Hallock (2018-01-01), "Dynamics of Stony Coral and Octocoral Juvenile Assemblages Following Disturbance on Patch Reefs of the Florida Reef Tract", Corals in a Changing World, retrieved 2025-11-24

- ^ Daniels, Camille; Zeifman, Amy; Heym, Kathy; Ritchie, Kim; Watson, Craig; Berzins, Ilze; Breitbart, Mya (2011-01-01). "Spatial Heterogeneity of Bacterial Communities in the Mucus of Montastraea annularis". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 426. doi:10.3354/meps09024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1134 - Coral Reefs and Sea Level Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Accessed December 16, 2010

- ^ Precht and Miller:266

- ^ Koch, Hanna R.; Matthews, Briana; Leto, Celia; Engelsma, Cody; Bartels, Erich (2022-12-08). "Assisted sexual reproduction of Acropora cervicornis for active restoration on Florida's Coral Reef". Frontiers in Marine Science. 9 959520. Bibcode:2022FrMaS...959520K. doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.959520. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Florida Keys Accessed December 17, 2010

- ^ "The World Of Artificial Reef Systems Off South Florida's Shores". Palm Beacher Magazine. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ^ NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program - Tourism and Recreation Accessed December 17, 2010

- ^ Socioeconomic Study of Reefs in Southeast Florida - Monroe County Accessed December 17, 2010

- ^ Socioeconomic Study of Reefs in Southeast Florida - Miami-Dade County Accessed December 17, 2010

- ^ Viele. Pp. 54-5

- ^ Langley and Parks:5

- ^ Blank:63

- ^ Viele 2001:3-14, 54-5, 166

Turner:27-8

Burnett:105

Facts about Monroe County Archived 2010-07-24 at the Wayback Machine Accessed December 17, 2010 - ^ Viele 1999:26-31, 92-94

- ^ "Historic Light Station Information and Photography: Florida". United States Coast Guard Historian's Office. Archived from the original on 2017-05-01.

- ^ Viele 2001:140, 154-59

United States Coast Guard Historic Light Station Information & Photography - Florida - American Shoal Light Accessed December 16, 2010 - ^ Blank:61-66

- ^ Agassiz, Louis. (1880) "Report on the Florida reefs." Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology VII:1. Harvard College. Accessed December 14, 2010

References

[edit]- Blank, Joan Gill. (1996) Key Biscayne. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56164-096-4

- Burnett, Gene. (1991) Florida's Past: People and Events That Shaped the State. Volume 3. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. ISBN 1-56164-117-0

- Langley, Wright and Arva Moore Parks (editors). (1983) "Diary of an Unidentified Land Official, 1855: Key West to Miami." Tequesta: The Journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida. Number XLIII. Found at UF Digital Collections Accessed December 19, 2010

- Luscombe, R. (2025, May 24). Scientists seek to save Florida's dying reefs with hardy nursery-grown coral; Reefs off the Keys have lost 90% of healthy coral cover in 40 years, but replanting effort aims to make reef more resilient. The Guardian [London]. Found at Scientists seek to save Florida's dying reefs with hardy nursery-grown coral; Reefs off the Keys have lost 90% of healthy coral cover in 40 years, but replanting effort aims to make reef more resilient. Accessed July 21, 2025

- Marszalek, D. S., G. Babashoff, Jr., M. R. Noel and D. R. Worley. (1977) "Reef Distribution in South Florida." Proceedings, Third International Coral Reef Symposium. Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami. Found at Wayback Machine Accessed December 18, 2010

- Precht, W. F. and S. L. Miller. (2007) "Ecological Shifts along the Florida Reef Tract: The Past as a Key to the Future." In R. B. Aronson. (Editor) Geological Approaches to Coral Reef Ecology. Found at [1] Accessed December 16, 2010

- Turner, Gregg. (2003) A Short History of Florida Railroads. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2421-2

- Viele, John. (1999) The Florida Keys: True Tales of the Perilous Straits. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56164-179-0

- Viele, John. (2001) The Florida Keys: The Wreckers. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56164-219-3

External links

[edit]- "Coral reefs in Florida." The Encyclopedia of Earth

- "Florida's large artificial reef system" CCCarto

- Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: Unified Reef Map

25°06′N 80°24′W / 25.1°N 80.4°W

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Joydeb (2015). "Hysteresis In Coral Reefs Under Macroalgal Toxicity And Overfishing". Journal of Biological Physics. 41 (2): 151–72. doi:10.1007/s10867-014-9371-y. PMC 4366437. PMID 25708511.

- ^ Hobbs, Jean-Paul A. (2013). "Taxonomic, Spatial And Temporal Patterns Of Bleaching In Anemones Inhabited By Anemonefishes". PLOS ONE. 8 (8) e70966. Plos. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...870966H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070966. PMC 3738586. PMID 23951056.

- ^ "NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program". coralreef.noaa. NOAA. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ Stevens, Alison Pearce. "Corals Dine On Microplastics". EBSCO. ." Science News For Students. Retrieved 13 April 2016.