Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Lake Assad.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

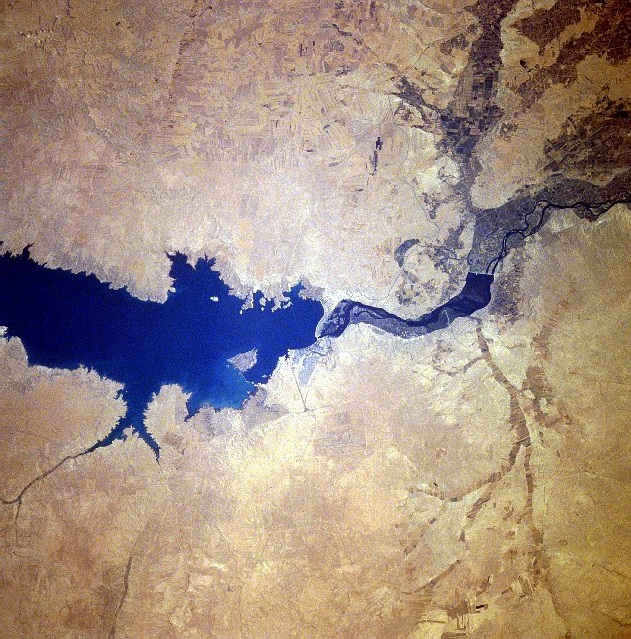

Lake Assad

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Redirect to:

This page is a redirect. The following categories are used to track and monitor this redirect:

|

Lake Assad

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia