Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Neolithic Revolution.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neolithic Revolution

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Neolithic Revolution

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

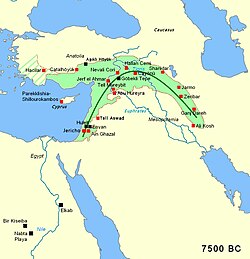

The Neolithic Revolution refers to the transition of prehistoric human societies from mobile hunter-gatherer lifestyles to sedentary agricultural communities through the domestication of plants and animals, initiating around 12,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia.[1] This process, centered initially on the domestication of cereals like emmer wheat and barley alongside caprines such as sheep and goats, enabled permanent villages and surplus food production, driving exponential population growth from roughly 5 million to over 100 million globally by 1 CE.[2][3] Key innovations included ground stone tools for processing grains and early herding practices evidenced by isotopic analysis of ancient dung, marking a causal shift from dependence on wild resources to managed ecosystems.[4] Despite these advances, the revolution imposed health costs, with skeletal remains showing reduced stature, increased enamel hypoplasia from nutritional stress, and higher infectious disease loads due to denser settlements and zoonotic transmissions from livestock.[5] Archaeological and genetic data reveal multiple independent origins of agriculture in regions like East Asia and the Americas, underscoring a gradual, adaptive diffusion rather than a singular "revolution," with ongoing debates over triggers like post-glacial warming versus demographic pressures.[6][7]