Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

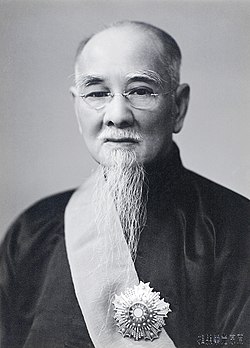

Lin Sen

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

Lin Sen (Chinese: 林森; pinyin: Lín Sēn; 16 March 1868 – 1 August 1943)[a] was a Chinese politician who served as Chairman of the National Government of the Republic of China from 1931 until his death in 1943.

Key Information

Early life

[edit]

Born to a middle-class family in Shanggan Township (尚幹鄉), Minhou County, Fuzhou, Lin was educated by American missionaries. He later worked in the Telegram Bureau of Taipei, Taiwan, in 1884. After the First Sino-Japanese War, he engaged in guerrilla activities against the Japanese occupiers. He returned to China and worked in the Shanghai customs office in 1902. He later lived in Hawaii and San Francisco.

There he was recruited by the Tongmenghui in 1905, and was an overseas organizer for the Kuomintang. During the Xinhai Revolution, he was in charge of the Jiangxi revolt. He became speaker of the senate in the National Assembly. After the failed Second Revolution against President Yuan Shikai, Lin fled with Sun Yat-sen to Japan and joined his Chinese Revolutionary Party. He was sent to the United States to raise funds from the party's local branches. In 1917, he followed Sun to Guangzhou where he continued to lead its "extraordinary session" during the Constitutional Protection Movement. When the assembly defected to the Beiyang government, he remained with Sun and later served as governor of Fujian.

Lin was a member of the right-wing Western Hills Group based in Shanghai. The group was formed in Beijing shortly after Sun's death in 1925. They called for a party congress to expel the Communists and to declare social revolution as incompatible with the Kuomintang's national revolution. The party pre-empted this faction and the ensuing congress expelled Western Hills' leaders and suspended the membership of the followers. They supported Chiang Kai-shek's purge of the communists in 1927. Lin rose to become the leader of the Western Hills faction and undertook a world tour after the demise of the Beiyang government.

As head of state

[edit]

In 1931, Chairman Chiang's arrest of Hu Hanmin caused an uproar within the party and military. Lin and other high-ranking officials called for the impeachment of Chiang. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria prevented the civil war from erupting, however it did cause Chiang to resign on 15 December. Lin was appointed in his place as acting chairman and confirmed as chairman of government on 1 January 1932. He was chosen as a sign of personal respect and held few powers since the Kuomintang wanted to avoid a repeat of Chiang's rule. He never used the Presidential Palace, where Chiang continued to reside, and preferred his modest rented house near the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum. Chiang's full influence was restored after the 1932 Battle of Shanghai as party grandees realized his necessity.

Shortly after acceding to the chairmanship, Lin Sen embarked on an extended trip that took him to the Philippines, Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and France. He visited the Chinese diaspora and the Kuomintang party organisations in those countries. This was the first overseas visit by a serving head of state of China.

In 1934, Time magazine called him "puppet President Lin", and when there was a talk by military chief Chiang Kai-shek at a "secret conference of government leaders" of granting the President of China actual powers, it insinuated that Chiang was entertaining the thought of taking the Presidency himself, since Chiang held the actual power while Lin's position was described as "figurehead class".[1]

Though he had little influence on public policy, Lin was highly respected by the public as an august elder statesman who was above politics. His lack of political ambition, corruption, and nepotism was an exceedingly rare trait. He lent dignity and stability to an office while other state institutions were in chaos.

A widower, Lin used his position to promote monogamy and combat concubinage which became a punishable felony in 1935. He also called for a peaceful resolution when Chiang was kidnapped during the Xi'an Incident. National unity was something he stressed as relations with Japan deteriorated further.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War entered full swing in 1937, he moved to the wartime capital of Chongqing. He legalized civilian use of guerrilla warfare, but this was merely a formality as it was already a widespread practice. He spurned all offers to defect and collaborate with the Japanese puppet government.

Death

[edit]On 10 March 1943, his car was involved in an accident. Two days later, he had a stroke while meeting the Canadian delegation. As he was in hospice, he urged the recovery of Taiwan be included in the post-war settlement; it became part of the Cairo Declaration months later. He died on 1 August, aged 75, following which a month of mourning was declared. He was the longest serving head of state in the Republic of China while it still held mainland China. The central executive committee elected Chiang as chairman of government a few hours after Lin's death. All of the powers that were denied to the chairmanship were restored for Chiang.

Lin visited Qingzhi Mountain in Lianjiang, Fuzhou, Fujian, and was fascinated by it, which encouraged him to style himself "Old Man Qingzhi" (青芝老人; Qīngzhī lǎorén) in his old age. His monument, built beside Qingzhi Mountain in 1926 before his death, was damaged in the Cultural Revolution, and was restored in 1979.

Family

[edit]Lin had adopted his nephew Lin Jing (known in English as K. M. James Lin), as his son. While studying as a postgraduate student in Ohio State University, James Lin married Viola Brown, a five-and-ten-cent store clerk, although he was reported already to have two wives in China. Lin Sen objected to the marriage and the couple eventually divorced. James Lin returned to China and died in action during the Japanese invasion.[2]

Legacy

[edit]

There are roads named after Lin Sen in Taipei, Kaohsiung, Tainan, and other towns and cities in Taiwan due to his role in fighting the Japanese invasion of Taiwan and as ROC president. A prominent statue of Lin Sen stands on Jieshou Park in front of the Presidential Office Building, Taipei.

In the People's Republic of China, Lin was denounced for his anti-communism and roads and places named after Lin Sen were renamed, but he was later rehabilitated after the Cultural Revolution.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Courtesy name Zi Chao (Chinese: 子超; Wade–Giles: Tze-chao), sobriquet Zhang Ren (長仁; Chang-jen)

References

[edit]- ^ "CHINA: Chiang on Lid". TIME. 20 August 1934. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "Son of China's President Reported Killed in Action". New York Times. 24 March 1938. p. 14.

Lin Sen

View on GrokipediaLin Sen (林森; March 16, 1868 – August 1, 1943) was a Chinese revolutionary and statesman who served as Chairman of the National Government of the Republic of China from December 1931 until his death, functioning largely as a ceremonial head of state amid the Japanese invasion and internal Nationalist-Communist tensions.[1] Born in Fujian Province during the Qing Dynasty, he participated in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, leading uprisings against Manchu rule and later organizing overseas support for Sun Yat-sen's republican cause.[1] His tenure, the longest for any Nationalist leader until 1949, symbolized continuity and moral authority in a government dominated by Chiang Kai-shek's executive power.[2] Lin Sen's early career included roles as a parliamentarian, foreign minister, and provincial governor, reflecting his commitment to constitutionalism and anti-warlord efforts within the Kuomintang (KMT).[1] A founder of the anti-communist Western Hills faction in 1925, he opposed leftist influences in the party, prioritizing national unification under conservative principles.[1] During the Second Sino-Japanese War, from the wartime capital of Chongqing, he authorized guerrilla resistance against Japanese forces in 1937 and enacted social reforms such as banning concubinage, underscoring his focus on ethical governance amid crisis.[1] Regarded for his humility and simplicity, Lin Sen maintained public respect as an elder statesman, declining overtures from Japanese puppet regimes and embodying stability until a stroke in March 1943 led to his death five months later, prompting a month of national mourning.[2][3] His passing elevated Chiang to acting president, marking the end of a figurehead era that bridged revolutionary ideals with wartime exigencies, though his influence remained subordinate to military leadership.[1]

Early Life and Revolutionary Origins

Birth, Family Background, and Education

Lin Sen was born on March 16, 1868, in Shangan village, Minhou County, near Fuzhou in Fujian Province, a coastal region of southeastern China known for its maritime trade and exposure to foreign influences during the late Qing Dynasty.[1] He came from a middle-class family of modest circumstances, with no recorded hereditary elite status but ties to local administrative or clerical roles common in Fujian gentry circles.[1] Such backgrounds often emphasized frugality and diligence amid the province's economic pressures from opium trade disruptions and treaty port openings.[2] His early education combined traditional Confucian learning with exposure to Western concepts through American missionary institutions prevalent in Fuzhou after the 1842 Treaty of Nanking opened the port.[3] At a private college, Lin studied classical Chinese texts, including Confucian ethics and historical annals, which formed the core of Qing-era schooling for aspiring literati.[3] Missionary schools supplemented this with self-directed reading in English-language materials on republican governance and science, introducing ideas of constitutionalism that contrasted with imperial autocracy, though Lin did not convert to Christianity.[1] This dual curriculum, verifiable in his later writings referencing both Mencius and Western political tracts, cultivated a pragmatic worldview blending moral rectitude with reformist aspirations.[4]Initial Involvement in Anti-Manchu Activities

Lin Sen, having witnessed the Qing dynasty's failures in modernizing China and resisting foreign powers such as during the Boxer Rebellion, turned toward revolutionary opposition to Manchu rule. In 1904, he traveled to Japan to study law, where exposure to republican ideologies among Chinese students prompted his entry into organized anti-Qing efforts. By 1905, he formally joined the Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Alliance) in Tokyo, the organization founded by Sun Yat-sen to unite disparate anti-Manchu groups under goals of expelling the Manchus, establishing a republic, and implementing land reforms.[1] Within the Tongmenghui, Lin Sen focused on propaganda dissemination, authoring and distributing pamphlets that decried the dynasty's ethnic alien rule and corruption, aiming to rally domestic and overseas support for uprisings. He also undertook fundraising missions among Chinese diaspora communities in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula, securing financial contributions to arm revolutionaries and evade Qing surveillance, which often forced him into hiding or exile. These activities underscored the logistical hurdles of early republican plotting, including limited arms and fragmented networks.[1] Lin participated in preparatory work for provincial revolts in Fujian, his home region, where local anti-Manchu sentiment ran high but executions faltered due to insufficient military coordination and intelligence leaks to Qing officials; for instance, aborted 1907-1908 attempts in the province collapsed amid betrayals and resource shortages, exemplifying the empirical setbacks that tempered revolutionary optimism prior to 1911. His early speeches and articles rejected dynastic legitimacy on grounds of ineffective governance and foreign subjugation, while tentatively exploring federalist ideas to accommodate China's regional diversity post-overthrow, though these remained marginal amid calls for immediate action.[1]Political Ascendancy in the Kuomintang

Alliance with Sun Yat-sen and Pre-1920s Roles

Lin Sen established his early alliance with Sun Yat-sen through membership in the Tongmenghui, the revolutionary alliance founded in 1905 to overthrow the Qing dynasty, where he actively participated in anti-Manchu plotting from overseas bases in Hawaii and the United States.[1][5] Following the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, which the Tongmenghui helped orchestrate, Lin led the Jiujiang uprising in Jiangxi province on October 23, 1911, contributing to the republican cause by mobilizing local New Army units against Qing forces.[1] This period marked his commitment to Sun's vision of nationalism, as evidenced by his role in propagating anti-imperialist sentiments among Chinese diaspora communities. As the Kuomintang (KMT) emerged in 1912 from the Tongmenghui's reorganization, Lin served as an overseas organizer, focusing on fundraising and recruitment drives among expatriate Chinese in the Americas to counter Yuan Shikai's authoritarian consolidation after he assumed the presidency on March 10, 1912.[1] These efforts targeted Yuan's suppression of parliamentary opposition, including the dissolution of the KMT in November 1913 following the failed Second Revolution. Lin's activities emphasized practical mobilization, channeling diaspora resources—estimated in the thousands of dollars through fraternal societies—to sustain revolutionary networks abroad.[6] Elected to the bicameral National Assembly formed on April 8, 1913, Lin advocated for constitutional governance amid the fragmentation into warlord fiefdoms post-Yuan's death in 1916, serving as Speaker of the Senate to uphold the Provisional Constitution's emphasis on representative institutions.[1] His tenure highlighted a dedication to Sun's Three Principles of the People, particularly nationalism against foreign encroachments and popular livelihood through land reforms, though implementation remained aspirational amid chaos. This alignment culminated in his appointment as Minister of Foreign Affairs in Sun's provisional military government in Guangzhou on July 17, 1917, where he helped administer early republican structures in southern China, prioritizing sovereignty and economic self-reliance over fragmented northern parliaments.[1]Positions in the 1920s and Right-Wing Factionalism

In 1921, Lin Sen was appointed speaker of the Guangzhou government's legislature, a role in which he contributed to legislative efforts amid the Kuomintang's (KMT) consolidation of power in southern China.[1] Shortly thereafter, he was named Nationalist governor of Fujian Province, serving briefly from November 31, 1922, to February 1923, with a focus on administrative stabilization to support preparations for the Northern Expedition against northern warlords.[1][7] Following Sun Yat-sen's death on March 12, 1925, Lin Sen co-founded the Western Hills Group in November 1925, a conservative right-wing faction of the KMT that emphasized fidelity to Sun's non-Bolshevik nationalist principles by demanding the expulsion of communists from party ranks and rejecting leftist ideological dilutions.[1] This group positioned itself against the influence of Soviet-backed elements within the KMT, viewing communist infiltration as incompatible with the party's foundational commitment to republican governance over class-based revolution.[1] As a prominent figure in the Western Hills faction, Lin advocated for anti-communist doctrinal purity during KMT Central Executive Committee deliberations in the mid-1920s, aligning with efforts to counter compromises by leftist leaders like Wang Jingwei, who favored continued cooperation with the Chinese Communist Party.[1] The faction's stance gained traction amid rising internal divisions, culminating in support for broader purges that reinforced the KMT's original anti-Bolshevik orientation, though it navigated tensions over party centralization without direct endorsement of militaristic consolidation.[1] Lin's involvement underscored a prioritization of ideological consistency over expedient alliances, framing right-wing positions as a defense of Sun's vision against foreign-inspired radicalism.[1]Tenure as Chairman of the National Government

Appointment Amid 1931 Political Crisis

In the wake of the Mukden Incident on September 18, 1931, which precipitated Japanese occupation of Manchuria, the Nationalist government in Nanjing faced compounded internal divisions, including a rival faction in Canton (Guangzhou) that had declared opposition to Chiang Kai-shek's leadership following his detention of Hu Hanmin in February.[8] This Canton group, comprising dissident Kuomintang (KMT) elements, threatened secession and established a parallel administration, intensifying pressure on the central authority amid ongoing Communist insurgencies in Jiangxi and widespread public agitation, including student riots demanding stronger resistance to Japan.[9] [10] Chiang Kai-shek, as Chairman of the National Government, resigned on December 15, 1931, in a calculated political maneuver to alleviate these pressures and reposition himself amid the factional strife and military commitments in Jiangxi, where KMT forces were engaged in suppression campaigns against Communist bases.[11] [12] The KMT's Central Executive Committee, seeking stability, selected Lin Sen on December 28, 1931, to assume the chairmanship, valuing his status as a veteran revolutionary and elder statesman who had participated in anti-Manchu activities since the 1900s and maintained prestige across KMT factions without direct entanglement in recent power struggles.[1] This choice aimed to provide ceremonial legitimacy to the Nanjing regime, countering the Cantonese challenge by projecting unity under a figure respected for his longevity in the party rather than military prowess.[3] Under the Organic Law of the National Government promulgated in October 1931, Lin Sen's role as Chairman conferred nominal executive authority, including the power to declare war, conclude treaties, and promulgate laws, but substantive decision-making resided with the KMT's Central Executive Committee and military affairs committees, reflecting the system's emphasis on party oversight over the head of state.[13] [14] Despite this structural limitation, Lin's independent moral standing within KMT lore—rooted in his early allegiance to Sun Yat-sen and avoidance of factional vendettas—afforded him a unifying symbolic influence that helped stabilize the government during the immediate transition, even as Chiang retained de facto control through military channels.[15]Administrative Role During the Nanjing Decade

During the Nanjing Decade from 1932 to 1937, Lin Sen's role as Chairman of the National Government involved presiding over formal sessions of the Kuomintang's Central Executive Committee and Legislative Yuan, where he endorsed policies aimed at administrative consolidation and economic stabilization, though substantive decision-making rested with Premier Chiang Kai-shek and the Executive Yuan.[1][2] The government, under this nominal oversight, advanced infrastructure initiatives, including the extension of railway networks from 11,000 kilometers in 1931 to over 15,000 kilometers by 1937, and urban redevelopment in Nanjing to symbolize centralized authority.[16] Lin signed decrees formalizing appointments in key institutions, such as university presidencies under the Ministry of Education, contributing to efforts at standardizing curricula and expanding primary schooling to reach approximately 20% enrollment growth in urban areas by mid-decade.[17] Banking reforms during this period, including the 1935 unification of currency under the fabi system managed by the Central Reserve Bank of China, were similarly ratified through Lin's ceremonial approvals, helping to curb inflation from 20-30% annual rates in the early 1930s and foster foreign investment inflows exceeding US$200 million by 1936.[16] However, these measures reflected Chiang's de facto control over fiscal policy via allies like T.V. Soong, with Lin's influence limited to symbolic ratification rather than initiation or enforcement, as evidenced by his deference in internal party disputes.[2] Government relocations, such as shifting provincial administrative branches to Nanjing, further centralized operations, but Lin's prior opposition to Chiang's 1931 arrest of Hu Hanmin underscored ongoing factional tensions that curtailed his policy autonomy.[2] In the 1936 Xi'an Incident, Lin Sen acted as the symbolic head of state, receiving Chiang Kai-shek upon his return to Nanjing on December 25 after negotiations secured his release without execution of the involved generals Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng.[1] This outcome aligned with the government's preference for dialogue over punitive military action, preserving unity amid Japanese threats, though Lin's direct input was constrained by Chiang's regained command post-release.[2] Overall, Lin's tenure emphasized procedural continuity and elder statesman dignity, counterbalancing Chiang's absolutist tendencies through formalist adherence to Sun Yat-sen's constitutional frameworks, yet without altering the underlying power dynamics.[1]Leadership During the Second Sino-Japanese War

Upon the outbreak of full-scale hostilities in the Second Sino-Japanese War following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident on July 7, 1937, Lin Sen endorsed legal measures to expand resistance capabilities. He signed legislation legalizing anti-Japanese guerrilla warfare, empowering civilians and irregular units to conduct operations independent of the regular National Revolutionary Army, which proved essential as Japanese forces overran conventional defenses and occupied major coastal and central regions.[1] This step facilitated decentralized combat networks amid the war's early phases, where Japanese aggression displaced millions and inflicted heavy casualties on Chinese forces. As Japanese troops captured Shanghai in November 1937 and Nanjing on December 13, 1937—entailing atrocities including mass executions and sexual violence that the International Military Tribunal for the Far East later documented as causing over 100,000 deaths based on eyewitness accounts and burial records—Lin Sen issued a declaration on November 20, 1937, announcing the capital's relocation to avert collapse of central authority.[18] The National Government, with Lin Sen as its titular head, coordinated evacuations first to Wuhan and then to Chongqing by October 1938, establishing a wartime base in Sichuan Province that symbolized unbroken sovereignty despite the loss of approximately 40% of China's pre-war territory and population centers.[19] This relocation, executed under his ceremonial oversight while Chiang Kai-shek directed military operations, sustained administrative functions and rallied public morale against the existential threat.[20] Lin Sen's wartime diplomacy involved formal appeals to Allied powers for material and moral support, drawing on his elder statesman status to affirm commitment to Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles amid the Second United Front with the Chinese Communist Party.[21] However, this KMT-CCP alliance remained superficial, serving as a temporary expedient for joint anti-Japanese efforts while enabling CCP forces to expand influence in rural base areas through autonomous guerrilla activities, foreshadowing post-war hostilities.[22][23] Though lacking substantive executive power—U.S. diplomatic assessments described him as an influential figurehead subordinate to Chiang—Lin Sen's representations in wartime cables and addresses bolstered China's international standing for aid, contributing to symbolic unity during the prolonged conflict that claimed an estimated 20 million Chinese lives by 1945.[20]Policy Contributions and Internal Relations

Key Domestic Reforms and Legal Measures

During his tenure as Chairman of the National Government, Lin Sen endorsed legal measures to curb concubinage, which was criminalized as a felony in 1935, reflecting an effort to restore Confucian ideals of monogamy in response to the polygamous practices prevalent among warlords and elites in preceding decades.[1] As a widower who exemplified personal adherence to monogamy, Lin leveraged his position to advocate against the practice, positioning it as a moral and social reform to stabilize family structures amid broader modernization efforts.[1] Lin supported anti-corruption initiatives within the Kuomintang framework, including drives to audit and penalize official malfeasance, though these were primarily executed by executive branches under Chiang Kai-shek's influence, with Lin's role limited to ceremonial approval and public endorsement to foster administrative integrity.[24] Similarly, he backed inquiries into land tenure systems during the 1930s, aimed at assessing rural ownership patterns to enhance stability without pursuing expropriatory redistribution that could incite unrest, aligning with conservative KMT priorities for agrarian order over revolutionary upheaval.[25] In the realm of women's rights, Lin facilitated KMT-backed expansions in female education and partial suffrage within party structures, as evidenced by government promotions of literacy campaigns and inheritance equality provisions extended from the 1930 Civil Code, though full electoral participation remained curtailed to maintain hierarchical control.[26] These measures emphasized gradual integration into national development rather than radical emancipation, reflecting Lin's conservative ideological commitments to social harmony over disruptive change.Interactions with Chiang Kai-shek and KMT Factions

Lin Sen's affiliation with the Western Hills Group, a conservative faction of the Kuomintang established in November 1925 at a conference in Western Hills near Beijing, positioned him as a staunch advocate for expelling communist elements from the party, reflecting his view of the Chinese Communist Party as an ideological and organizational threat to KMT unity and nationalist goals.[2] This anti-communist consistency predated his chairmanship and persisted through pre-war purges, including the 1927 Shanghai Massacre under Chiang Kai-shek, where over 300,000 suspected communists and leftists were executed or suppressed nationwide, actions Lin supported as necessary to eliminate CCP infiltration despite their scale. His factional role emphasized causal realism in internal politics, prioritizing the eradication of subversive influences over ideological harmony. Tensions with Chiang Kai-shek emerged most acutely during the 1931 crisis over Hu Hanmin's arrest, when Chiang, on February 28, detained the Legislative Yuan president without due process to consolidate executive power amid disputes over constitutional checks. Lin Sen, having succeeded Hu in the Legislative Yuan, dissented by co-authorizing an impeachment against Chiang for the illegal act on April 30, 1931, alongside figures like Ku Ying-fen and Teng Ze-ru, framing it as a violation of party protocols and Sun Yat-sen's legacy.[27] This principled opposition, rooted in right-wing commitments to limited authoritarianism, exacerbated the uproar that forced Chiang's temporary resignation on December 15, 1931, elevating Lin to acting chairman as a compromise to restore stability without endorsing unchecked purges.[28] As chairman from 1932, Lin maintained a courteous but distant relationship with Chiang, leveraging his elder statesman status to bridge rightist factions against both Chiang's centralizing impulses and leftist challenges, such as Wang Jingwei's opposition during the 1930 Central Plains War aftermath. By mediating among Western Hills holdouts and advocating restrained reconciliation—evident in his role stabilizing the Nanjing regime post-1931 without capitulating to factional extremes—Lin prevented schisms that could have fragmented KMT resistance to Japanese aggression and CCP expansion.[20] This balancing act underscored empirical factional realism, checking Chiang's authoritarian consolidation while upholding anti-communist vigilance, as seen in Lin's endorsement of ongoing expulsions of CCP sympathizers from KMT ranks through the 1930s. His restraint served not as deference but as a counterweight, preserving institutional dignity amid power struggles.Personal Life and Character

Family and Private Affairs

Lin Sen contracted an arranged marriage at age 14 to a woman surnamed Zheng, who died soon after, rendering him a widower without biological children; he remained unmarried for the rest of his life.[29] Lacking direct heirs, he adopted his nephew Lin Jing as his son circa 1915, treating him as his own.[30] Lin Jing pursued postgraduate studies at Ohio State University in the United States and married an American woman, initially against Lin Sen's wishes, though paternal acceptance followed by 1935.[31] He returned to China, joining the military, and died in combat against Japanese forces at Taiyuan in 1937, leaving no known descendants to carry the family line after Lin Sen's own death in 1943.[32] During his tenure, Lin Sen resided in standard official accommodations in Nanjing and Chongqing, eschewing the luxurious estates associated with figures like Chiang Kai-shek.[33] His personal expenditures reflected frugality; he allocated his monthly stipend of 20,000 yuan primarily to acquiring calligraphy and paintings, underscoring his scholarly inclinations over material indulgence.Personal Traits and Ideological Commitments

Lin Sen was renowned among contemporaries for his personal integrity, frugality, and aversion to political intrigue, traits that distinguished him in the fractious Kuomintang leadership. He lived modestly, maintaining a simple residence in Nanjing with a large garden but eschewing luxury, and earlier in San Francisco occupied a single barren room.[3] His nickname "Tzu-ch'ao," interpreted as denoting self-governance or independence, reflected his reputation for principled detachment from factional maneuvering, earning him descriptions as gentle, kindly, and humorously wise—embodying the proverb "Great Wisdom Looks Like Stupidity."[3] In public addresses, he emphasized frugality as essential for national resilience amid wartime challenges.[21] Ideologically, Lin Sen maintained lifelong commitments to federalism and opposition to totalitarian structures, critiquing both the decentralized chaos of warlordism and the centralized Bolshevik model as incompatible with China's needs for balanced self-rule. As a key figure in the right-wing Western Hills Group, he advocated for disciplined party governance while favoring provincial autonomy over rigid centralization. His anti-totalitarian stance aligned with broader KMT efforts to purge communist influences, viewing them as threats to republican ideals. Lin Sen's worldview was deeply rooted in Confucian traditions, as evidenced by his traditional Chinese education and practice of calligraphy on Confucian classics.[34] He rejected excesses of Western materialism, prioritizing moral self-cultivation and ritual propriety over unchecked modernization, and supported Confucian institutions by appointing descendants of Confucius to ceremonial roles, such as designating Kung Teh-cheng as Duke Yansheng in 1935. This devotion underscored his preference for ethical governance grounded in classical Chinese virtues rather than imported ideological extremes.[3]Death, Succession, and Short-Term Impact

Circumstances of Death and Health Decline

In early 1943, Lin Sen's health began to deteriorate amid the strains of wartime leadership in Chongqing, the Nationalist government's wartime capital after the 1937 Japanese invasion forced repeated relocations from Nanjing. On March 10, he was involved in a car accident that exacerbated his physical frailty at age 75.[1] Two days later, on March 12, Lin suffered a stroke while receiving a Canadian diplomatic delegation, marking the onset of severe complications including partial paralysis and confinement to hospice care.[1] A second stroke struck on May 12, further weakening him as he attempted to fulfill ceremonial duties, such as accepting credentials from Canada's first minister to China; official reports described his condition as critical but did not release detailed medical bulletins beyond confirming cerebrovascular events linked to chronic fatigue from years of political exile and administrative burdens during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[3] These incidents, compounded by the austere living conditions in Chongqing's rugged terrain and limited medical resources amid ongoing conflict, accelerated his decline without evidence of alternative causes like infection or poisoning in contemporaneous accounts. Lin Sen died on August 1, 1943, in Chongqing from stroke-related complications, having served as Chairman of the National Government for over eleven years.[1] His passing occurred in the presidential villa suburb, prompting immediate memorial rites on August 7 in an adjoining pavilion, where Kuomintang leaders gathered to honor him as a symbol of continuity amid adversity; the funeral emphasized national mourning without disruption to war efforts.[35]Transition of Power and Immediate Consequences

Following Lin Sen's death from a stroke on August 1, 1943, the Kuomintang (KMT) leadership moved swiftly to ensure continuity, appointing Chiang Kai-shek as acting chairman of the National Government on the same day.[1] This interim role bridged the gap until Chiang's formal election as chairman on October 10, 1943, thereby merging supreme military command—already held by Chiang as generalissimo—with the civilian presidency.[3] The transition formalized Chiang's de facto dominance, as Lin Sen's role had been largely ceremonial amid the wartime exigencies of the Second Sino-Japanese War.[36] A period of national mourning lasting one month was declared, during which memorial services were held in Chongqing, underscoring Lin's symbolic importance despite his limited executive power.[2] U.S. diplomatic assessments noted that immediate succession questions were resolved without factional strife, averting any near-term instability in the Nationalist regime.[37] Policy continuity prevailed, with no abrupt changes; the government's priority remained the prosecution of the war against Japan, including coordination with Allied forces, as evidenced by ongoing military operations and diplomatic engagements.[1] This seamless handover reinforced perceptions of institutional resilience within the KMT, temporarily stabilizing Allied confidence in China's wartime contributions despite underlying challenges like corruption and internal divisions.[37] Chiang's assumption of the dual role streamlined decision-making but also highlighted the personalization of authority, as civil-military boundaries blurred further under the pressures of total war.[36]Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Reception in Nationalist China and Taiwan

In the Republic of China, Lin Sen has been honored as a veteran Kuomintang leader and elder statesman whose tenure as Chairman of the National Government from 1931 to 1943 symbolized steadfast adherence to Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People amid wartime exigencies and internal factionalism.[15] His role in providing ceremonial and moral continuity during the Second Sino-Japanese War is emphasized in Nationalist historiography as essential to preserving republican institutions against both Japanese imperialism and communist insurgency.[2] Following the Nationalist government's retreat to Taiwan in 1949, Lin Sen's legacy was actively commemorated through public infrastructure and events, reinforcing anti-communist narratives of continuity. Streets named after him, including Linsen Road (Lin Sen Road) in Taipei's Zhongzheng District, were established to recognize his leadership in the anti-Japanese resistance and his status as the longest-serving head of state before the relocation.[38] The centennial of his birth in 1968 was marked by official observances in Taiwan, portraying him as a long-time associate of Sun Yat-sen and a pillar of the Republic's founding ideals.[39] Recent scholarly access to primary materials has bolstered affirmative evaluations of Lin Sen's diligence. The Hoover Institution's 2025 acquisition of his personal papers, including administrative documents from his chairmanship, documents his hands-on involvement in governance despite the position's largely titular nature, underscoring contributions to wartime relocation efforts and factional mediation that sustained Nationalist unity.[2] While some analyses highlight his limited executive power relative to Chiang Kai-shek, these archives affirm his independent initiatives in exile planning and ethical oversight, framing him as a stabilizing force in the KMT's anti-communist framework rather than a mere figurehead.Treatment in the People's Republic of China

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Lin Sen faced denunciation as a prominent Kuomintang reactionary, implicated in enabling anti-communist suppression and Chiang Kai-shek's consolidation of power. This initial vilification manifested in the systematic removal of honors bestowed by the prior regime, such as the redesignation of Fujian Province's Minhou County—renamed Lin Sen County on August 11, 1944, shortly after his death—to its pre-1944 name in April 1950 upon Communist administrative control.[40][41] Such actions underscored the Mao-era imperative to erase Nationalist symbols, framing Lin's tenure as National Government chairman (1931–1943) as antithetical to proletarian revolution, despite his pre-1927 revolutionary alliances. Maoist historiography, through campaigns like those critiquing the "century of humiliation" and bourgeois legacies, further entrenched this portrayal by emphasizing Lin's role in perpetuating a "feudal-fascist" KMT dictatorship, while marginalizing empirical evidence of his anti-imperialist stances, such as declaring war on Japan in December 1941. These assessments prioritized causal narratives of class struggle over balanced causal analysis, suppressing Lin's federalist proposals for provincial self-governance as deviations that could undermine unitary state authority, thereby serving ideological consolidation rather than objective evaluation. Post-Cultural Revolution reforms from the late 1970s onward introduced selective rehabilitation, acknowledging Lin's Tongmenghui membership and contributions to Sun Yat-sen's early republican efforts as part of China's "democratic revolution" stage. Official narratives began highlighting his personal integrity and anti-Qing activities, as seen in local histories praising his frugality amid wartime leadership.[42] Yet this restoration omitted scrutiny of his nominal presidency's limitations in checking authoritarian tendencies, and avoided rehabilitating federalist alternatives he championed, with no reversals of 1950s renamings. This pragmatic shift, amid broader post-Mao reevaluations of Republican achievements for legitimacy, reveals historiography driven by regime needs over unvarnished empirical reckoning.[43]Balanced Assessments of Achievements and Limitations

Lin Sen's tenure as Chairman of the National Government from December 1931 to his death in 1943 provided a measure of institutional continuity and symbolic legitimacy to the Republic of China amid escalating internal factionalism and external aggression, particularly during the Second Sino-Japanese War starting in 1937.[1] His signing of legislation legalizing anti-Japanese guerrilla warfare in 1937 formalized resistance efforts, enabling broader mobilization against invasion while maintaining the facade of constitutional governance.[1] Additionally, he contributed significantly to the 1930s outlawing of concubinage, a reform aimed at modernizing family law and aligning with republican ideals of equality, though enforcement remained uneven due to entrenched customs.[1] These actions, while limited in scope, bolstered morale and international perception of the Nationalist regime's endurance. However, Lin's role as a largely ceremonial figurehead curtailed his substantive influence, with real executive authority residing with Chiang Kai-shek and military leaders, rendering him unable to curb the Kuomintang's authoritarian tendencies or address systemic corruption that eroded public support.[44] [20] This powerlessness contributed causally to the regime's failure to consolidate control, as Lin lacked the leverage to mediate factional disputes effectively or implement transformative policies against the Chinese Communist Party's territorial gains in rural areas during the war. Critics, including contemporary diplomatic assessments, noted his status as an "elder statesman of no appreciable influence," highlighting how symbolic presidency prioritized stability over decisive leadership in a chaotic era.[20] In balanced historical evaluations, Lin's steadfast anti-communist alignment as a founding Kuomintang member preserved ideological coherence for the Nationalist cause, earning praise from right-leaning observers for upholding republican principles against Bolshevik expansion amid global turmoil.[45] Yet, his achievements were predominantly facilitative rather than initiatory, stabilizing the government symbolically without altering underlying power dynamics or averting the KMT's eventual mainland retreat in 1949; he served as a stabilizing elder in crisis but not a pivotal reformer capable of reshaping China's trajectory.[2]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Organic_Law_of_the_National_Government_of_the_Republic_of_China_%281931%29