Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mu (rocket family)

View on Wikipedia

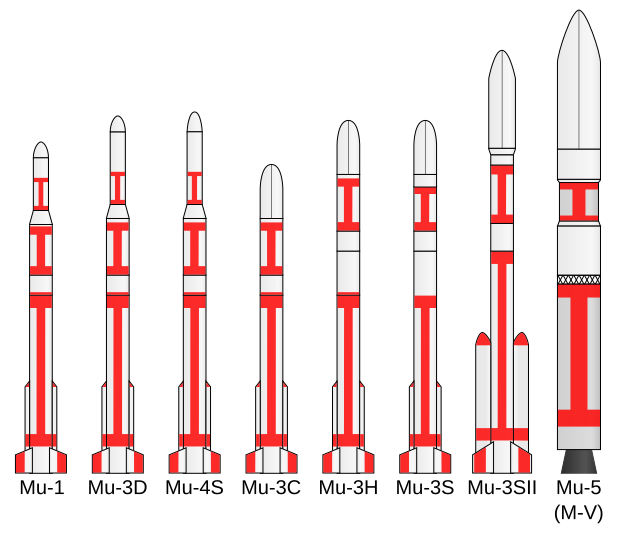

The Mu, also known as M, was a series of Japanese solid-fueled carrier rockets, which were launched from Uchinoura between 1966 and 2006. Originally developed by Japan's Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Mu rockets were later operated by JAXA following ISAS becoming part of it.[1]

Early Japanese carrier rockets

[edit]The first Mu rocket, the Mu-1 made a single, sub-orbital, test flight, on 31 October 1966. Subsequently, a series of rockets were produced, designated Mu-3 and Mu-4. In 1969 a suborbital test launch of the Mu-3D was conducted.[2] The first orbital launch attempt for the Mu family, using a Mu-4S, was conducted on 25 September 1970, however the fourth stage did not ignite, and the rocket failed to reach orbit. On 16 February 1971, Tansei 1 was launched by another Mu-4S rocket. Two further Mu-4S launches took place during 1971 and 1972. The Mu-4S was replaced by the Mu-3C, was launched four times between 1974 and 1979, with three successes and one failure, and the Mu-3H, which was launched three times in 1977 and 1978. The Mu-3S was used between 1980 and 1984, making four launches. The final member of the Mu-3 family was the Mu-3SII, which was launched eight times between 1985 and 1995. The Mu-3 was replaced in service by the M-V.

M-V

[edit]The M-V, or Mu-5, was introduced in 1997 and retired in 2006. Seven launches, six of which were successful, were conducted. Typically, the M-V flew in a three-stage configuration, however a four-stage configuration, designated M-V KM was used 3 times, with the MUSES-B (HALCA) satellite in 1997, Nozomi (PLANET-B) spacecraft in 1998, and the Hayabusa (MUSES-C) spacecraft in 2003. The three-stage configuration had a maximum payload of 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) for an orbit with altitude of 200 km (120 mi) and inclination of 30°, and 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) to a polar orbit (90° inclination), with an altitude of 200 km (120 mi). The M-V KM could launch 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) to an orbit with 30° inclination and 400 km (250 mi) altitude.

The three stage M-V had a total launch mass of 137,500 kg (303,100 lb), whilst the total mass of a four-stage M-V KM was 139,000 kg (306,000 lb).

List of launches

[edit]All launches are from the Mu Launch Pad at the Uchinoura Space Center.

| Flight number | Date (UTC) | Payload | Orbit | Result | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-4S-1 | September 25, 1970 05:00 |

MS-F1 | LEO (planned) | Failure | |

| M-4S-2 | February 16, 1971 04:00 |

MS-T1 (Tansei 1) | LEO | Success | |

| M-4S-3 | September 28, 1971 04:00 |

MS-F2 (Shinsei) | LEO | Success | |

| M-4S-4 | August 19, 1972 02:40 |

REXS (Denpa) | MEO | Success | |

| M-3C-1 | February 16, 1974 05:00 |

MS-T2 (Tansei 2) | MEO | Success | |

| M-3C-2 | February 24, 1975 05:25 |

SRATS (Taiyo) | MEO | Success | |

| M-3C-3 | February 4, 1976 05:00 |

CORSA | LEO (planned) | Failure | |

| M-3H-1 | February 19, 1977 05:15 |

MS-T3 (Tansei 3) | MEO | Success | |

| M-3H-2 | February 4, 1978 07:00 |

EXOS-A (Kyokko) | MEO | Success | |

| M-3H-3 | September 16, 1978 05:00 |

EXOS-B (Jikiken) | HEO | Success | |

| M-3C-4 | February 21, 1979 05:00 |

CORSA-b (Hakucho) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3S-1 | February 17, 1980 00:40 |

MS-T4 (Tansei 4) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3S-2 | February 21, 1981 00:30 |

ASTRO-A (Hinotori) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3S-3 | February 20, 1983 05:10 |

ASTRO-B (Tenma) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3S-4 | February 14, 1984 08:00 |

EXOS-C (Ohzora) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3SII-1 | January 7, 1985 19:26 |

MS-T5 (Sakigake) | HTO | Success | |

| M-3SII-2 | August 18, 1985 23:33 |

PLANET-A (Suisei) | HTO | Success | |

| M-3SII-3 | February 5, 1987 06:30 |

ASTRO-C (Ginga) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3SII-4 | February 21, 1989 23:30 |

EXOS-D (Akebono) | MEO | Success | |

| M-3SII-5 | January 24, 1990 11:46 |

MUSES-A (Hiten) | LTO | Success | |

| M-3SII-6 | August 30, 1991 02:30 |

SOLAR-A (Yohkoh) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3SII-7 | February 20, 1993 02:20 |

ASTRO-D/ASCA (Asuka) | LEO | Success | |

| M-3SII-8 | January 15, 1995 13:45 |

EXPRESS | LEO | Partial failure | |

| M-V-1 | February 12, 1997 04:50 |

MUSES-B/HALCA (Haruka) | HEO | Success | |

| M-V-3 | July 3, 1998 18:12 |

PLANET-B (Nozomi) | HTO | Success | |

| M-V-4 | February 10, 2000 01:30 |

ASTRO-E | LEO (planned) | Failure | |

| M-V-5 | May 9, 2003 04:29 |

MUSES-C (Hayabusa) | HTO | Success | |

| M-V-6 | July 10, 2005 03:30 |

ASTRO-EII (Suzaku) | LEO | Success | |

| M-V-8 | February 21, 2006 21:28 |

ASTRO-F (Akari) | LEO | Success | |

| M-V-7 | September 22, 2006 21:36 |

SOLAR-B (Hinode) | LEO | Success |

^Note Two sub-orbital launches of the Mu family were performed prior to its first orbital flight: the 1.5 stage Mu-1 flew on October 31, 1966, at 05:04 UTC and the 3.5 stage Mu-3D flew on August 17, 1969, at 06:00 UTC.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]External links

[edit]Mu (rocket family)

View on GrokipediaDevelopment History

Origins in Sounding Rockets

Japan's rocketry program originated in the mid-1950s under the University of Tokyo's Institute of Industrial Science, driven by the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-1958 and collaborations with international bodies like COSPAR and NASA.[3][4] Led by Hideo Itokawa, early efforts focused on small-scale sounding rockets for meteorological and upper-atmosphere research, including ionospheric studies, cosmic ray measurements, and atmospheric wind and temperature profiling.[5] These initiatives laid the groundwork for Japan's independent space capabilities, with initial launches conducted from sites like Michigawa in Akita Prefecture before the establishment of the Kagoshima Space Center in 1962.[4] The Kappa series marked Japan's first dedicated sounding rocket program, spanning 1958 to 1965 and representing the nation's inaugural exoatmospheric launches.[3] Early models like the K-6, launched in June 1958, achieved 60 km altitudes using liquid propellants and enabled Japan's IGY participation with 12 kg payloads for telemetry data collection.[4] A pivotal milestone came with the two-stage Kappa-8 in 1962, which reached an apogee of 200 km, facilitating advanced ionosphere and cosmic ray observations in the presence of NASA representatives.[5] The series evolved through variants like the K-9M, attaining 400 km altitudes with 40-50 kg payloads, emphasizing Japan's growing expertise in upper-atmosphere science.[4] Building on Kappa's successes, the Lambda series (1964-1967) introduced larger, four-stage solid-fuel designs to probe deeper into the upper atmosphere, targeting apogees of 1,000 km or more.[2] Developed for the International Quiet Sun Year (1964-1965), Lambda rockets featured innovations like the 735 mm diameter L-735 engine, tested extensively from 1961-1962 for combustion analysis.[4] The Lambda-4's inaugural launch in September 1966 represented a partial step toward orbital capabilities, though full success came later, underscoring the program's shift toward more ambitious missions.[5] This progression from liquid to solid propellants across Kappa and Lambda enhanced reliability and performance for sounding missions, culminating in the Mu family's designation in 1966 as a direct evolution for sustained atmospheric research.[2][5]Evolution to Orbital Capabilities

The transition from sounding rockets to orbital capabilities in Japan's space program accelerated in the early 1970s, building on the lessons from the Lambda 4S series. Following a failure of the Lambda 4S on September 22, 1969, due to a fourth-stage control system malfunction after the third stage collided with it, the program achieved success with the Lambda 4S-5 launch of the Ohsumi satellite on February 11, 1970, marking Japan's first domestically developed all-solid-propellant orbital insertion.[5] This paved the way for the Mu series, developed by the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), which emphasized reliable, all-solid-propellant designs for scientific satellite deployments. ISAS, established in 1963 under the University of Tokyo, leveraged its expertise in solid-propellant rocketry—honed through earlier Kappa and Lambda programs—to lead the Mu's evolution as a dedicated orbital launcher, prioritizing indigenous technology for space science missions.[6] The Mu series' first orbital success came with the M-4S configuration, launching the Tansei (MS-T1) technology test satellite on February 16, 1971, into a near-circular low Earth orbit of approximately 1,000 km altitude. This followed a failed attempt on September 25, 1970, with the MS-F1 technology test satellite, where the fourth stage failed to ignite.[7] This mission demonstrated the vehicle's ability to inject payloads of around 65 kg into orbit, validating gravity-turn trajectory techniques and attitude stabilization via spin. Subsequent M-4S launches in 1971 and 1972, including the Shinsei (MS-F2) in September 1971 and Denpa (MS-T2 or REX) in August 1972 into an elliptical orbit with a perigee of approximately 240 km and apogee of 6,500 km, further refined orbital insertion reliability for electromagnetic and solar observation satellites.[2][8] By the late 1970s, iterative improvements in the M-3C (introduced 1974) and M-3H (1977) variants enhanced payload capacity to approximately 200 kg for the M-3C and 300 kg for the M-3H in low Earth orbit, enabling more ambitious missions like the Kyokko (EXOS-A) auroral satellite in 1978.[2][9][10] Key engineering challenges in achieving consistent orbital performance were addressed through innovations in thrust vector control (TVC), tested on the Kappa-10C sounding rocket in 1969–1970. The Kappa-10C flights developed jet-deflection TVC systems to enable precise attitude adjustments in solid motors, mitigating issues like nozzle heat shield failures observed in early tests; these advancements were integrated into later Mu stages, starting with the second-stage SITVC in the M-3C. International collaborations, including component testing with U.S. partners under NASA's technical exchange programs, supported ISAS in validating TVC actuators and guidance systems, ensuring the Mu's transition to a versatile orbital platform without liquid-propellant dependencies.[5] These developments were driven by Japan's post-World War II policy emphasis on technological self-reliance in space, intensified by the 1973 oil crisis that highlighted vulnerabilities in imported energy and technology. The crisis prompted a national push for independent capabilities, positioning the Mu as ISAS's flagship for scientific autonomy, as outlined in the 1975 Science Council of Japan report promoting space research for long-term national security and innovation. This aligned with broader 1970s reforms, including the 1969 Diet resolution on peaceful space use, which allocated resources to ISAS for solid-propellant advancements amid economic pressures.[11][6]Design and Technology

Propulsion and Stages

The Mu rocket family employed an all-solid propellant architecture, leveraging composite solid propellants to enable reliable, storable propulsion systems suitable for scientific satellite launches.[12] These propellants, typically consisting of ammonium perchlorate as the oxidizer combined with aluminum fuel and a polymer binder, provided high energy density and simplicity in ignition compared to liquid-fueled alternatives.[13] The design emphasized indigenous development after initial influences from U.S. technology, with all stages powered by solid rocket motors that burned sequentially to achieve orbital insertion. Staging in the Mu series evolved from four-stage configurations in early variants like the M-4S to three-stage setups in later models such as the Mu-3, M-3S, and M-V, optimizing for payload capacity and mission flexibility.[2] Interstage separation relied on pyrotechnic devices, including explosive bolts and linear shaped charges, to ensure clean disconnection and minimize structural interference during ascent.[14] For instance, early Mu variants built on technology influenced by U.S. designs from the Lambda series, while upper stages were fully Japanese-developed, with redundant ignition systems using pyrotechnic initiators to enhance reliability against failure modes like incomplete combustion.[2] Performance parameters across the family highlighted the efficiency of solid propulsion, with specific impulses generally ranging from 260 to 280 seconds in vacuum for main stages, enabling velocity increments sufficient for low Earth orbit insertion.[12] First-stage motors delivered thrust levels of 30 to 40 tons (approximately 300 to 400 kN) in early configurations, scaling up to over 3,800 kN in the M-V's advanced first stage for greater liftoff capability.[15] Key innovations included the adoption of high-energy propellants in later iterations, such as enhanced formulations in the M-V's BP-series motors (e.g., 72 tons of propellant in stage 1 yielding 274 seconds specific impulse), and thrust vector control via gimbaled nozzles or secondary injection systems to improve trajectory accuracy without compromising the solid design's simplicity.[15] Fairings, with diameters increasing from about 1.4 meters for early models like the M-3S to 2.5 meters for the M-V, incorporated ablative materials for thermal protection during atmospheric reentry of upper stages.[12][15] Total impulse calculations for ascent profiles underscored the family's progression, with payload capacities to low Earth orbit increasing from about 300 kg for the Mu-3 to 1,800 kg for the M-V, driven by optimized propellant mass fractions and staging efficiency.[2][16] Reliability was bolstered by features like dual-redundant igniters and ground-tested motor casings, contributing to a success rate exceeding 90% across 30 launches.[2]Guidance and Control Systems

The Mu rocket family's guidance systems primarily relied on inertial navigation, utilizing gyroscopes and accelerometers to track vehicle attitude and velocity during ascent.[17] Early variants, such as the M-3S, employed a Spin Free Analytical Platform (SFAP) with rate-integrating gyroscopes for pitch, yaw, and roll measurements, complemented by radio command updates from ground stations to refine third-stage ignition timing, with up to four corrections possible.[17] Later models like the M-V advanced to strapdown fiber optic gyroscopes (FOG) in a radio-inertial setup, enhancing compactness and reliability without gimbaled platforms.[16] Control mechanisms integrated thrust vector control (TVC) through liquid injection into the first and second stages, using Freon or similar agents via proportional valves to adjust nozzle deflection for pitch and yaw.[17] The first stage of the M-3S activated TVC intermittently (e.g., 6-20 seconds and 40-65 seconds post-launch) with eight electro-hydraulically driven valves, while solid motor roll control nozzles provided 20 kgf thrust for roll stabilization starting at 4 seconds.[17] Upper stages employed spin stabilization, with the second stage of the Mu-3 series spun up to approximately 2 revolutions per second (120 rpm) via side jets fueled by hydrogen peroxide, transitioning to three-axis control post-burnout; the M-V extended TVC to movable nozzles on all three stages, with side jets handling roll.[17][16] This TVC approach was integrated with propulsion systems to enable precise trajectory corrections without mechanical gimballing in early solid-propellant designs.[2] The evolution of these systems progressed from analog-based setups in the Mu-3 era to digital inertial navigation in the M-V, incorporating strapdown FOG for improved attitude sensing and achieving 0.1-degree accuracy in pointing.[16] Initial Mu-3 configurations used analog gyro platforms and on-off injection valves for TVC, limited by secondary injection methods, whereas the M-V's digital INS drew on precursors to modern satellite navigation technologies, such as advanced gyro integration, to support more autonomous operations.[18][16] Key components included onboard sequencing electronics for stage separation and payload deployment, often built by Japanese firms like NEC for 1980s models, handling guidance logic at frequencies up to 40 Hz for attitude and 1.25 Hz for trajectory updates in the Mu-3S.[18] These systems managed automated events like spin-up motors and jet firings, ensuring reliable payload fairing jettison and satellite release.[17] Performance improved markedly across the family, with orbit insertion errors decreasing from around 10 km in 1970s Mu-3 launches to under 1 km by the 2000s M-V flights, driven by refined TVC and inertial sensing.[2] Early test failures, such as those in Mu-3C second-stage guidance due to TVC valve malfunctions, informed subsequent designs, reducing anomaly rates through better injection reliability and radio overrides.[17][16]Rocket Variants

Early Mu Configurations

The early Mu configurations, developed by Japan's Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS) in the late 1960s and 1970s, built directly on the Lambda sounding rocket heritage to enable reliable low-Earth orbit insertions for small scientific satellites using all-solid propellant technology. These initial models emphasized simplicity, spin stabilization, and iterative enhancements in stage performance and guidance accuracy, paving the way for Japan's independent space access. All launches occurred from the Uchinoura Space Center, with total masses ranging from 37 to 62 tons depending on the variant.[2][19][20][21] The M-4S, introduced in 1970 as the inaugural orbital-capable Mu, featured a four-stage design with a total length of 23.6 meters and a launch mass of 43,710 kg, capable of delivering up to 180 kg to a 200 km low-Earth orbit. It employed a gravity-turn trajectory for payload injection and relied on tail fins combined with spin for attitude control, reflecting foundational solid-rocket engineering from the Lambda series. The program's debut flight (M-4S-1) in September 1970 failed due to third-stage separation issues, but the M-4S-2 mission on February 16, 1971, successfully orbited the Tansei 1 (MS-T) technological satellite at 520 km altitude, achieving Japan's first fully successful domestic orbital launch. Follow-on successes included the Shinsei X-ray astronomy satellite in September 1971 and the Denpa plasma wave observatory in August 1972, demonstrating the configuration's viability for scientific payloads despite early reliability challenges.[19][2][22] Succeeding the M-4S, the M-3C debuted in 1974 with a refined three-stage architecture that prioritized orbital precision through a newly developed second stage incorporating secondary injection thrust vector control (SITVC) and a third stage with side-jet attitude systems. Standing 20.2 meters tall with a launch mass of 37,445 kg, it supported payloads of 195 kg to low-Earth orbits, including sun-synchronous paths up to 500 km altitude, enabling more accurate satellite deployments than its predecessor. The configuration's inaugural flight orbited the Tansei 2 satellite in February 1974, followed by the Taiyo solar observatory in February 1975; however, a 1976 launch failed owing to second-stage thrust vector control malfunction. A later success came with the Hakucho X-ray astronomy satellite in 1979, underscoring the M-3C's role in advancing Japan's space-based observations.[20][2] The M-3H, entering service in 1977, extended the M-3C's lineage into a four-stage (plus optional kick stage) variant optimized for heavier payloads via an elongated first stage with enhanced propellant loading, resulting in a 23.8-meter height and 61,765 kg launch mass for up to 300 kg to low-Earth orbit. Primarily solid-fueled throughout, it offered flexibility for upper-stage adaptations while maintaining the family's emphasis on cost-effective scientific missions. Its debut flight successfully deployed the Tansei 3 magnetosphere probe in February 1977, with subsequent launches carrying the Kyokko auroral imager in February 1978 and the Jikiken ionosphere explorer in September 1978, all achieving nominal orbits. These efforts highlighted incremental reliability gains, though the early Mu series overall contended with two stage-separation anomalies that informed subsequent designs.[21][2]Mu-3 Series

The Mu-3 series represented a significant evolution in Japan's solid-propellant launch capabilities during the 1980s and early 1990s, building on earlier Mu variants to enable more reliable insertion of scientific satellites into low Earth orbit (LEO). Developed by the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), these rockets emphasized incremental improvements in payload capacity, structural efficiency, and guidance precision, primarily for astrophysics and planetary science missions. The series shared common design elements, including a multi-stage solid-fuel configuration and a focus on cost-effective operations for small-to-medium payloads, achieving an overall high success rate across approximately a dozen flights.[2] The baseline Mu-3S, introduced in the early 1980s, served as the foundation for the series with a payload capacity of around 300 kg to LEO at a 250 km altitude. Measuring 23.8 m in length and 1.41 m in diameter, it featured three solid-propellant stages with a total launch mass of about 49 tons. A key innovation was the incorporation of thrust vector control (TVC) on the first stage, which enhanced trajectory accuracy and reduced weather-related launch constraints compared to prior models. The Mu-3S conducted four successful launches from Uchinoura Space Center, deploying satellites such as Tansei-4 (a technology test satellite) in February 1980, Hinotori (ASTRO-B, an X-ray astronomy observatory) in February 1981, Tenma (ASTRO-A, focused on X-ray bursts) in February 1983, and Ohzora (EXOS-C, for auroral studies) in January 1984; all missions achieved nominal orbits, demonstrating 100% reliability for this variant.[12][2][23] The Mu-3SII, operational from 1985 onward, marked the series' final iteration with upgrades to boost performance for more demanding payloads. Retaining the Mu-3S first stage but replacing upper stages with lighter, higher-efficiency designs—including an optional fourth-stage kick motor for precise orbit circularization—it extended the payload capacity to 770 kg in LEO. The rocket stood 27.8 m tall with a 1.65 m diameter, supporting a 2.5 m fairing for larger satellites, and incorporated advanced attitude control systems for interplanetary trajectories. Over eight launches, it achieved seven successes (87.5% rate), including the Halley's Comet probes Sakigake (January 1985) and Suisei (August 1985), which flew by the comet in 1986; Ginga (ASTRO-C, X-ray observatory) in February 1987; and Akebono (EXOS-D, aurora mission) in February 1989. The sole failure occurred in January 1995 during the Express satellite launch due to second-stage attitude control issues, preventing orbital insertion.[24][2][23][25] Across the Mu-3S and Mu-3SII, shared features included solid-propellant motors with specific impulses ranging from 238-293 seconds and a modular staging approach that facilitated rapid integration of scientific payloads. The kick motor enabled fine adjustments for sun-synchronous or geocentric orbits, contributing to the series' versatility for astronomy and magnetospheric research. With a cumulative success rate exceeding 80% over 12 flights, the Mu-3 series solidified ISAS's independence in small satellite launches before transitioning to more advanced vehicles.[12][24]M-V Launcher

The M-V rocket represented the culmination of the Mu family's evolution, serving as Japan's primary launcher for advanced scientific satellites and interplanetary probes from 1997 to 2006. Developed by the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (now part of JAXA), it built upon the Mu-3 series' solid-propellant heritage to accommodate larger payloads requiring precise insertion into low Earth orbit (LEO) or higher-energy trajectories. The vehicle stood 30.8 meters tall, measured 2.5 meters in diameter, and had a gross liftoff mass of approximately 140 metric tons, enabling it to deliver up to 1,800 kg to a 250 km LEO.[16] Its configuration included three solid-propellant stages plus an optional hydrazine-based kick stage for geostationary transfer orbit (GTO) or escape missions, emphasizing reliability for deep-space applications. The first launch occurred on February 12, 1997, successfully deploying the HALCA radio astronomy satellite, though a subsequent mission in 2000 failed due to a first-stage motor anomaly.[26][15] Key design features enhanced its performance for scientific payloads, including a lightweight carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) structure for the upper stages and extendable nozzles on the first and second stages to optimize thrust in vacuum conditions. The first stage employed the M-14 solid motor, generating 3,800 kN of thrust with a specific impulse of 274 seconds and a burn time of 51 seconds, fueled by 72 tons of propellant. Subsequent stages featured the M-25 motor (1,530 kN thrust, 289 seconds specific impulse) and M-34 motor (327 kN thrust, 300 seconds specific impulse), enabling velocity increments suitable for polar orbits or interplanetary injections when paired with the kick stage. A 2.5-meter-diameter fairing provided payload protection, while the guidance system incorporated a digital flight computer for fully autonomous operations, using fiber-optic gyroscopes for attitude control and thrust vectoring via secondary injection. These elements allowed the M-V to support missions demanding high accuracy, such as X-ray astronomy and planetary exploration.[15][27] The M-V conducted seven launches from the Uchinoura Space Center (now Kagoshima Space Center), achieving six successes for an 86% reliability rate. Notable missions included the Nozomi Mars orbiter on July 4, 1998, which reached a hyperbolic escape trajectory despite later mission challenges; the Hayabusa asteroid sample-return probe on May 9, 2003, marking Japan's first interplanetary sample mission; and the AKARI infrared astronomy satellite (formerly Astro-F) on February 22, 2006. Other successes encompassed the HALCA (1997), Suzaku X-ray observatory (2005), and Hinode solar observatory (2006), collectively advancing astrophysics and planetary science. The sole failure involved the Astro-E X-ray satellite on February 10, 2000, resulting from a nozzle crack in the first-stage motor that caused loss of telemetry and prevented orbital insertion.[26]| Launch Date | Flight No. | Payload | Outcome | Orbit/Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997-02-12 | M-V-1 | HALCA | Success | Highly elliptical Earth orbit |

| 1998-07-04 | M-V-3 | Nozomi | Success | Mars transfer (escape) |

| 2000-02-10 | M-V-4 | Astro-E | Failure | N/A (first-stage anomaly) |

| 2003-05-09 | M-V-5 | Hayabusa | Success | Earth escape to Itokawa |

| 2005-07-10 | M-V-6 | Suzaku | Success | Low Earth orbit |

| 2006-02-22 | M-V-8 | AKARI (Astro-F) | Success | Sun-synchronous orbit |

| 2006-09-23 | M-V-7 | Hinode | Success | Sun-synchronous orbit |