Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Space research

View on Wikipedia

Space research is scientific study carried out in outer space, and by studying outer space. From the use of space technology to the observable universe, space research is a wide research field. Earth science, materials science, biology, medicine, and physics all apply to the space research environment. The term includes scientific payloads at any altitude from deep space to low Earth orbit, extended to include sounding rocket research in the upper atmosphere, and high-altitude balloons.

Space exploration is also a form of space research.

History

[edit]

Rockets

[edit]Chinese rockets were used in ceremony and as weaponry since the 13th century, but no rocket would overcome Earth's gravity until the latter half of the 20th century. Space-capable rocketry appeared simultaneously in the work of three scientists, in three separate countries. In Russia, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, in the United States, Robert H. Goddard, and in Germany, Hermann Oberth.

The United States and the Soviet Union created their own missile programs. The space research field evolved as scientific investigation based on advancing rocket technology.

In 1948–1949 detectors on V-2 rocket flights detected x-rays from the Sun.[1] Sounding rockets helped show us the structure of the upper atmosphere. As higher altitudes were reached, space physics emerged as a field of research with studies of Earths aurorae, ionosphere and magnetosphere.

Artificial satellites

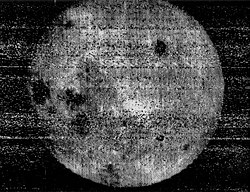

[edit]The first artificial satellite, Russian Sputnik 1, launched on October 4, 1957, four months before the United States first, Explorer 1. The major discovery of satellite research was in 1958, when Explorer 1 detected the Van Allen radiation belts. Planetology reached a new stage with the Russian Luna programme, between 1959 and 1976, a series of lunar probes which gave us evidence of the Moons chemical composition, gravity, temperature, soil samples, the first photographs of the far side of the Moon by Luna 3, and the first remotely controlled robots (Lunokhod) to land on another planetary body.

International co-operation

[edit]The early space researchers obtained an important international forum with the establishment of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) in 1958, which achieved an exchange of scientific information between east and west during the cold war, despite the military origin of the rocket technology underlying the research field.[2]

Astronauts

[edit]On April 12, 1961, Russian Lieutenant Yuri Gagarin was the first human to orbit Earth, in Vostok 1. In 1961, US astronaut Alan Shepard was the first American in space. And on July 20, 1969, astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were the first humans on the Moon.

On April 19, 1971, the Soviet Union launched the Salyut 1, the first space station of substantial duration, a successful 23 day mission, sadly ruined by transport disasters. On May 14, 1973, Skylab, the first American space station launched, on a modified Saturn V rocket. Skylab was occupied for 24 weeks.[3]

Extent

[edit]

486958 Arrokoth is the name of the farthest and most primitive object visited by human spacecraft. Originally designated "1110113Y" when detected by Hubble Space Telescope in 2014, the planetessimal was reached by the New Horizons probe on 1 January 2019 after a week long manoeuvering phase. New Horizons detected Ultima Thule from 107 million miles and performed a total 9 days of manoeuvres to pass within 3,500 miles of the 19 mile long contact binary. Ultima Thule has an orbital period around 298 years, is 4.1 billion miles from Earth, and over 1 billion miles beyond Pluto.

Interstellar

[edit]The Voyager 1 probe launched on 5 September 1977, and flew beyond the edge of the Solar System in August 2012 to the interstellar medium. The farthest human object from the Earth, predictions include collision, an Oort cloud, and destiny, "perhaps eternally—to wander the Milky Way."

Voyager 2 launched on 20 August 1977 travelling slower than Voyager 1 and reached interstellar medium by the end of 2018. Voyager 2 is the only Earth probe to have visited the ice giants of Neptune or Uranus

Neither Voyager is aimed at a particular visible object, but both continue to send research data to NASA Deep Space Network as of 2019.

Two Pioneer probes and the New Horizons probe are expected to enter interstellar medium in the near future, but these three are expected to have depleted available power before then, so the point of exit cannot be confirmed precisely. Predicting probes speed is imprecise as they pass through the variable heliosphere. Pioneer 10 is roughly at the outer edge of the heliosphere in 2019. New Horizons should reach it by 2040, and Pioneer 11 by 2060.

Two Voyager probes have reached interstellar medium, and three other probes are expected to join that list.

Research fields

[edit]Space research includes the following fields of science:[4][5]

- Earth observations, using remote sensing techniques to interpret optical and radar data from Earth observation satellites

- Geodesy, using gravitational perturbations of satellite orbits

- Atmospheric sciences, aeronomy using satellites, sounding rockets and high-altitude balloons

- Space physics, the in situ study of space plasmas, e.g. aurorae, the ionosphere, the magnetosphere and space weather

- Planetology, using space probes to study objects in the planetary system

- Astronomy, using space telescopes and detectors that are not limited by looking through the atmosphere

- Materials sciences, taking advantage of the micro-g environment on orbital platforms

- Life sciences, including human physiology, using the space radiation environment and weightlessness, also growing Plants in space

- Physics, using space as a laboratory for studies in fundamental physics.

Space research from artificial satellites

[edit]Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite

[edit]Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite was a NASA-led mission launched on September 12, 1991. The 5,900 kg (13,000 lb) satellite was deployed from the Space Shuttle Discovery during the STS-48 mission on 15 September 1991. It was the first multi-instrumented satellite to study various aspects of the Earth's atmosphere and have a better understanding of photochemistry. After 14 years of service, the UARS finished its scientific career in 2005.[6]

Great Observatories program

[edit]

Great Observatories program is the flagship NASA telescope program. The Great Observatories program pushes forward our understanding of the universe with detailed observation of the sky, based in gamma rays, ultraviolet, x-ray, infrared, and visible, light spectrums. The four main telescopes for the Great Observatories program are, Hubble Space Telescope (visible, ultraviolet), launched 1990, Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (gamma), launched 1991 and retired 2000, Chandra X-Ray Observatory (x-ray), launched 1999, and Spitzer Space Telescope (infrared), launched 2003.

Origins of the Hubble, named after American astronomer Edwin Hubble, go back as far as 1946. In the present day, the Hubble is used to identify exo-planets and give detailed accounts of events in the Solar System. The Hubble Space Telescope's visible-light observations are combined with the other great observatories to provide some of the most detailed images of the visible universe.

International Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory

[edit]INTEGRAL is one of the most powerful gamma-ray observatories, launched by the European Space Agency in 2002, and continuing to operate (as of March 2019). INTEGRAL provides insight into the most energetic cosmological formations in space including, black holes, neutron stars, and supernovas.[7] INTEGRAL plays an important role researching gamma-rays, one of the most exotic and energetic phenomena in space.

Gravity and Extreme Magnetism Small Explorer

[edit]The NASA-led GEMS mission was scheduled to launch for November 2014.[8] The spacecraft would use an X-Ray telescope to measure the polarization of x-rays coming from black holes and neutron stars. It would research into remnants of supernovae, stars that have exploded. Few experiments have been conducted in X-Ray polarization since the 1970s, and scientists anticipated GEMS to break new ground. Understanding x-ray polarisation will improve scientists knowledge of black holes, in particular whether matter around a black hole is confined, to a flat-disk, a puffed disk, or a squirting jet. The GEMS project was cancelled in June 2012, projected to fail time and finance limits. The purpose of the GEMS mission continues to be relevant (as of 2019).

Space research on space stations

[edit]

Salyut 1

[edit]Salyut 1 was the first space station built. It was launched on April 19, 1971 by the Soviet Union. The first crew failed entry into the space station. The second crew was able to spend twenty-three days in the space station, but this achievement was quickly overshadowed since the crew died on reentry to Earth. Salyut 1 was intentionally deorbited six months into orbit since it prematurely ran out of fuel.[9]

Skylab

[edit]Skylab was the first American space station. It was four times larger than Salyut 1. Skylab was launched on May 14, 1973. It rotated through three crews of three during its operational time. Skylab's experiments confirmed coronal holes and were able to photograph eight solar flares.[10]

Mir

[edit]Soviet (later Russian) station Mir, from 1986 to 2001, was the first long term inhabited space station. Occupied in low Earth orbit for twelve and a half years, Mir served a permanent microgravity laboratory. Crews experimented with biology, human biology, physics, astronomy, meteorology and spacecraft systems. Goals included developing technologies for permanent occupation of space.

International Space Station

[edit]

The International Space Station received its first crew as part of STS-88, in December 1998, an internationally co-operative mission of almost 20 participants. The station has been continuously occupied for 24 years and 359 days, exceeding the previous record, almost ten years by Russian station Mir.[11] The ISS provides research in microgravity, and exposure to the local space environment. Crew members conduct tests relevant to biology, physics, astronomy, and others. Even studying the experience and health of the crew advances space research.

See also

[edit]

- Advances in Space Research (journal)

- Benefits of space exploration

- Committee on Space Research (COSPAR)

- Deep space exploration

- Lists of space programs

- Outer space

- Space Age

- Space archaeology

- Space architecture

- Space exploration

- Spacefaring

- Space law

- Space medicine

- Space probe

- Space research service (space research radio frequencies)

- Space science

References

[edit]- ^ A Brief History of High-Energy Astronomy: 1900-1958, NASA web page

- ^ Willmore, Peter: COSPAR’s first 50 years, Public Lecture

- ^ A Brief History of Space Exploration | The Aerospace Corporation. (n.d.). The Aerospace Corporation | Assuring Space Mission Success. Retrieved May 7, 2013

- ^ COSPAR Scientific Structure, COSPAR web page

- ^ Advances in Space Research, Elsevier web page

- ^ UARS Science main page. (n.d.). UARS Science main page. Retrieved May 7

- ^ ESA Science & Technology: Fact Sheet. (n.d.). ESA Science and Technology. Retrieved May 6, 2013

- ^ GEMS

- ^ Salyut 1 Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved May 7, 2013

- ^ The SkyLab Project. (n.d.). Solar Physics Branch Home Page, Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved May 7, 2013

- ^ NASA - Facts and Figures. (n.d.). NASA - Home. Retrieved May 7, 2013

External links

[edit] Media related to Space research at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Space research at Wikimedia Commons