Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mass number

View on Wikipedia| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

The mass number (symbol A, from the German word: Atomgewicht, "atomic weight"),[1] also called atomic mass number or nucleon number, is the total number of protons and neutrons (together known as nucleons) in an atomic nucleus. It is approximately equal to the atomic (also known as isotopic) mass of the atom expressed in daltons. Since protons and neutrons are both baryons, the mass number A is identical with the baryon number B of the nucleus (and also of the whole atom or ion). The mass number is different for each isotope of a given chemical element, and the difference between the mass number and the atomic number Z gives the number of neutrons (N) in the nucleus: N = A − Z.[2]

The mass number is written either after the element name or as a superscript to the left of an element's symbol. For example, the most common isotope of carbon is carbon-12, or 12

C, which has 6 protons and 6 neutrons. The full isotope symbol would also have the atomic number (Z) as a subscript to the left of the element symbol directly below the mass number: 12

6C.[3]

Mass number changes in radioactive decay

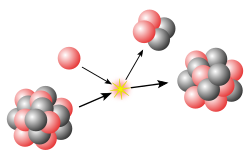

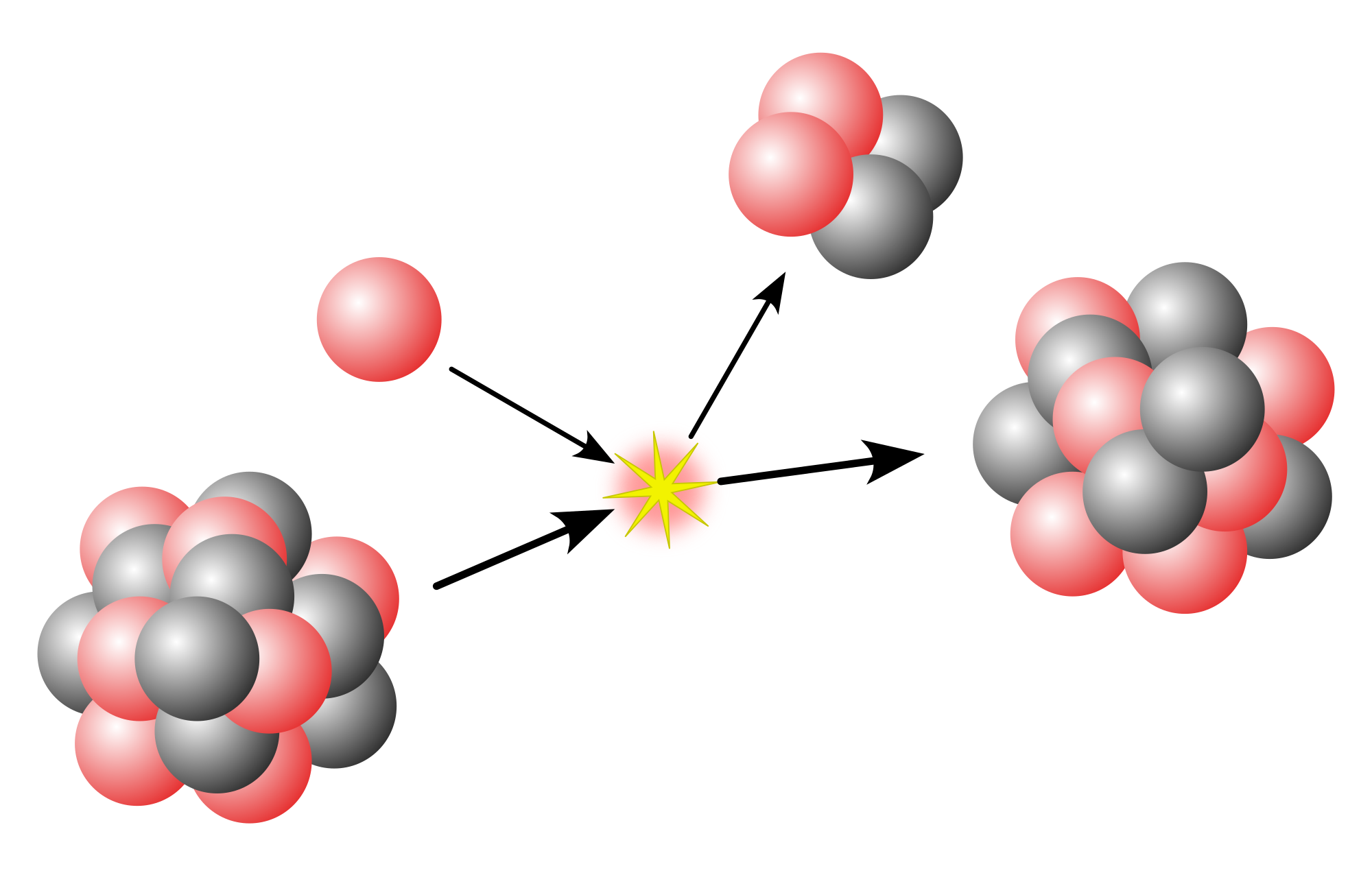

[edit]Different types of radioactive decay are characterized by their changes in mass number as well as atomic number, according to the radioactive displacement law of Fajans and Soddy.

For example, uranium-238 usually decays by alpha decay, where the nucleus loses two neutrons and two protons in the form of an alpha particle. Thus the atomic number and the number of neutrons each decrease by 2 (Z: 92 → 90, N: 146 → 144), so that the mass number decreases by 4 (A = 238 → 234); the result is an atom of thorium-234 and an alpha particle (4

2He2+

):[4]

238

92U→ 234

90Th+ 4

2He2+

On the other hand, carbon-14 decays by beta decay, whereby one neutron is transmuted into a proton with the emission of an electron and an antineutrino. Thus the atomic number increases by 1 (Z: 6 → 7) and the mass number remains the same (A = 14), while the number of neutrons decreases by 1 (N: 8 → 7).[5] The resulting atom is nitrogen-14, with seven protons and seven neutrons:

14

6C→ 14

7N+ e−

+ ν

e

Beta decay is possible because different isobars[6] have mass differences on the order of a few electron masses. If possible, a nuclide will undergo beta decay to an adjacent isobar with lower mass. In the absence of other decay modes, a cascade of beta decays terminates at the isobar with the lowest atomic mass.

Another type of radioactive decay without change in mass number is emission of a gamma ray from a nuclear isomer or metastable excited state of an atomic nucleus. Since all the protons and neutrons remain in the nucleus unchanged in this process, the mass number is also unchanged.

Mass number and isotopic mass

[edit]The mass number gives an estimate of the isotopic mass measured in daltons (Da). For 12C, the isotopic mass is exactly 12, since the dalton is defined as 1/12 of the mass of 12C. For other isotopes, the isotopic mass is usually within 0.1 Da of the mass number. For example, 35Cl (17 protons and 18 neutrons) has a mass number of 35 and an isotopic mass of 34.96885.[7] The difference of the actual isotopic mass minus the mass number of an atom is known as the mass excess,[8] which for 35Cl is –0.03115. Mass excess should not be confused with mass defect, which is the difference between the mass of an atom and its constituent particles (namely protons, neutrons and electrons).

There are two reasons for mass excess:

- The neutron is slightly heavier than the proton. This increases the mass of nuclei with more neutrons than protons relative to the dalton based on 12C with equal numbers of protons and neutrons.

- Nuclear binding energy varies between nuclei. A nucleus with greater binding energy has a lower total energy, and therefore a lower mass according to Einstein's mass–energy equivalence relation E = mc2. For 35Cl, the isotopic mass is less than 35, so this must be the dominant factor.

Relative atomic mass of an element

[edit]The mass number should also not be confused with the standard atomic weight (also called atomic weight) of an element, which is the ratio of the average atomic mass of the different isotopes of that element (weighted by abundance) to the atomic mass constant.[9] The atomic weight is a mass ratio, while the mass number is a counted number (and so an integer).

This weighted average can be quite different from the near-integer values for individual isotopic masses. For instance, there are two main isotopes of chlorine: chlorine-35 and chlorine-37. In any given sample of chlorine that has not been subjected to mass separation there will be roughly 75% of chlorine atoms which are chlorine-35 and only 25% of chlorine atoms which are chlorine-37. This gives chlorine a relative atomic mass of 35.5 (actually 35.4527 g/mol).

Moreover, the weighted average mass can be near-integer, but at the same time not corresponding to the mass of any natural isotope. For example, bromine has only two stable isotopes, 79Br and 81Br, naturally present in approximately equal fractions, which leads to the standard atomic mass of bromine close to 80 (79.904 g/mol),[10] even though the isotope 80Br with such mass is unstable.

References

[edit]- ^ Jensen, William B. (2005). The Origins of the Symbols A and Z for Atomic Weight and Number. J. Chem. Educ. 82: 1764. link.

- ^ "How many protons, electrons and neutrons are in an atom of krypton, carbon, oxygen, neon, silver, gold, etc. ...?". Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Elemental Notation and Isotopes". Science Help Online. Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ Suchocki, John. Conceptual Chemistry, 2007. Page 119.

- ^ Curran, Greg (2004). Homework Helpers. Career Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 1-56414-721-5.

- ^ Atoms with the same mass number.

- ^ Wang, M.; Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Xu, X. (2017). "The AME2016 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs, and references". Chinese Physics C. 41 (3) 030003. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030003.

- ^ "Mass excess, Δ". The IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.M03719.

- ^ "Relative atomic mass (Atomic weight), Ar". The IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.R05258.

- ^ "Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements". NIST.

Further reading

[edit]- Bishop, Mark. "The Structure of Matter and Chemical Elements (ch. 3)". An Introduction to Chemistry. Chiral Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-9778105-4-3. Retrieved 2008-07-08.