Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nucleosynthesis

View on Wikipedia

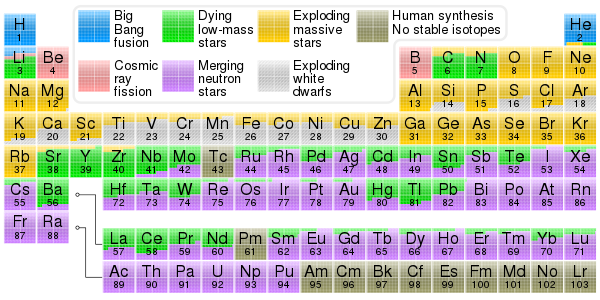

Nucleosynthesis is the process that creates new atomic nuclei from pre-existing nucleons (protons and neutrons) and nuclei. According to current theories, the first nuclei were formed a few minutes after the Big Bang, through nuclear reactions in a process called Big Bang nucleosynthesis.[1] After about 20 minutes, the universe had expanded and cooled to a point at which these high-energy collisions among nucleons ended, so only the fastest and simplest reactions occurred, leaving our universe containing hydrogen and helium. The rest is traces of other elements such as lithium and the hydrogen isotope deuterium. Nucleosynthesis in stars and their explosions later produced the variety of elements and isotopes that we have today, in a process called cosmic chemical evolution. The amounts of total mass in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium (called 'metals' by astrophysicists) remains small (few percent), so that the universe still has approximately the same composition.

Stars fuse light elements to heavier ones in their cores, giving off energy in the process known as stellar nucleosynthesis. Nuclear fusion reactions create many of the lighter elements, up to and including iron and nickel in the most massive stars. Products of stellar nucleosynthesis remain trapped in stellar cores and remnants except if ejected through stellar winds and explosions. The neutron capture reactions of the r-process and s-process create heavier elements, from iron upwards.

Supernova nucleosynthesis within exploding stars is largely responsible for the elements between oxygen and rubidium: from the ejection of elements produced during stellar nucleosynthesis; through explosive nucleosynthesis during the supernova explosion; and from the r-process (absorption of multiple neutrons) during the explosion.

Neutron star mergers are a recently discovered major source of elements produced in the r-process. When two neutron stars collide, a significant amount of neutron-rich matter may be ejected which then quickly forms heavy elements.

Cosmic ray spallation is a process wherein cosmic rays impact nuclei and fragment them. It is a significant source of the lighter nuclei, particularly 3He, 9Be and 10,11B, that are not created by stellar nucleosynthesis. Cosmic ray spallation can occur in the interstellar medium, on asteroids and meteoroids, or on Earth in the atmosphere or in the ground. This contributes to the presence on Earth of cosmogenic nuclides.

On Earth new nuclei are also produced by radiogenesis, the decay of long-lived, primordial radionuclides such as uranium, thorium, and potassium-40.

History

[edit]

Timeline

[edit]It is thought that the primordial nucleons themselves were formed from the quark–gluon plasma around 13.8 billion years ago during the Big Bang as it cooled below two trillion degrees. A few minutes afterwards, starting with only protons and neutrons, nuclei up to lithium and beryllium (both with mass number 7) were formed, but hardly any other elements. Some boron may have been formed at this time, but the process stopped before significant carbon could be formed, as this element requires a far higher product of helium density and time than were present in the short nucleosynthesis period of the Big Bang. That fusion process essentially shut down at about 20 minutes, due to drops in temperature and density as the universe continued to expand. This first process, Big Bang nucleosynthesis, was the first type of nucleogenesis to occur in the universe, creating the so-called primordial elements.

A star formed in the early universe produces heavier elements by combining its lighter nuclei – hydrogen, helium, lithium, beryllium, and boron – which were found in the initial composition of the interstellar medium and hence the star. Interstellar gas therefore contains declining abundances of these light elements, which are present only by virtue of their nucleosynthesis during the Big Bang, and also cosmic ray spallation. These lighter elements in the present universe are therefore thought to have been produced through thousands of millions of years of cosmic ray (mostly high-energy proton) mediated breakup of heavier elements in interstellar gas and dust. The fragments of these cosmic-ray collisions include helium-3 and the stable isotopes of the light elements lithium, beryllium, and boron. Carbon was not made in the Big Bang, but was produced later in larger stars via the triple-alpha process.

The subsequent nucleosynthesis of heavier elements (Z ≥ 6, carbon and heavier elements) requires the extreme temperatures and pressures found within stars and supernovae. These processes began as hydrogen and helium from the Big Bang collapsed into the first stars after about 500 million years. Star formation has been occurring continuously in galaxies since that time. The primordial nuclides were created by Big Bang nucleosynthesis, stellar nucleosynthesis, supernova nucleosynthesis, and by nucleosynthesis in exotic events such as neutron star collisions. Other nuclides, such as 40Ar, formed later through radioactive decay. On Earth, mixing and evaporation has altered the primordial composition to what is called the natural terrestrial composition. The heavier elements produced after the Big Bang range in atomic numbers from Z = 6 (carbon) to Z = 94 (plutonium). Synthesis of these elements occurred through nuclear reactions involving the strong and weak interactions among nuclei, and called nuclear fusion (including both rapid and slow multiple neutron capture), and include also nuclear fission and radioactive decays such as beta decay. The stability of atomic nuclei of different sizes and composition (i.e. numbers of neutrons and protons) plays an important role in the possible reactions among nuclei. Cosmic nucleosynthesis, therefore, is studied among researchers of astrophysics and nuclear physics ("nuclear astrophysics").

History of nucleosynthesis theory

[edit]The first ideas on nucleosynthesis were simply that the chemical elements were created at the beginning of the universe, but no rational physical scenario for this could be identified. Gradually it became clear that hydrogen and helium are much more abundant than any of the other elements. All the rest constitute less than 2% of the mass of the Solar System, and of other star systems as well. At the same time it was clear that oxygen and carbon were the next two most common elements, and also that there was a general trend toward high abundance of the light elements, especially those with isotopes composed of whole numbers of helium-4 nuclei (alpha nuclides).

Arthur Stanley Eddington first suggested in 1920 that stars obtain their energy by fusing hydrogen into helium and raised the possibility that the heavier elements may also form in stars.[2][3] This idea was not generally accepted, as the nuclear mechanism was not understood. In the years immediately before World War II, Hans Bethe first elucidated those nuclear mechanisms by which hydrogen is fused into helium.

Fred Hoyle's original work on nucleosynthesis of heavier elements in stars, occurred just after World War II.[4] His work explained the production of all heavier elements, starting from hydrogen. Hoyle proposed that hydrogen is continuously created in the universe from vacuum and energy, without need for universal beginning.

Hoyle's work explained how the abundances of the elements increased with time as the galaxy aged. Subsequently, Hoyle's picture was expanded during the 1960s by contributions from William A. Fowler, Alastair G. W. Cameron, and Donald D. Clayton, followed by many others. The seminal 1957 review paper by E. M. Burbidge, G. R. Burbidge, Fowler and Hoyle[5] is a well-known summary of the state of the field in 1957. That paper defined new processes for the transformation of one heavy nucleus into others within stars, processes that could be documented by astronomers.

The Big Bang itself had been proposed in 1931, long before this period, by Georges Lemaître, a Belgian physicist, who suggested that the evident expansion of the Universe in time required that the Universe, if contracted backwards in time, would continue to do so until it could contract no further. This would bring all the mass of the Universe to a single point, a "primeval atom", to a state before which time and space did not exist. Hoyle is credited with coining the term "Big Bang" during a 1949 BBC radio broadcast, saying that Lemaître's theory was "based on the hypothesis that all the matter in the universe was created in one big bang at a particular time in the remote past". It is popularly reported that Hoyle intended this to be pejorative, but Hoyle explicitly denied this and said it was just a striking image meant to highlight the difference between the two models. Lemaître's model was needed to explain the existence of deuterium and nuclides between helium and carbon, as well as the fundamentally high amount of helium present, not only in stars but also in interstellar space. As it happened, both Lemaître and Hoyle's models of nucleosynthesis would be needed to explain the elemental abundances in the universe.

The goal of the theory of nucleosynthesis is to explain the vastly differing abundances of the chemical elements and their several isotopes from the perspective of natural processes. The primary stimulus to the development of this theory was the shape of a plot of the abundances versus the atomic number of the elements. Those abundances, when plotted on a graph as a function of atomic number, have a jagged sawtooth structure that varies by factors up to ten million. A very influential stimulus to nucleosynthesis research was an abundance table created by Hans Suess and Harold Urey that was based on the unfractionated abundances of the non-volatile elements found within unevolved meteorites.[6] Such a graph of the abundances is displayed on a logarithmic scale below, where the dramatically jagged structure is visually suppressed by the many powers of ten spanned in the vertical scale of this graph.

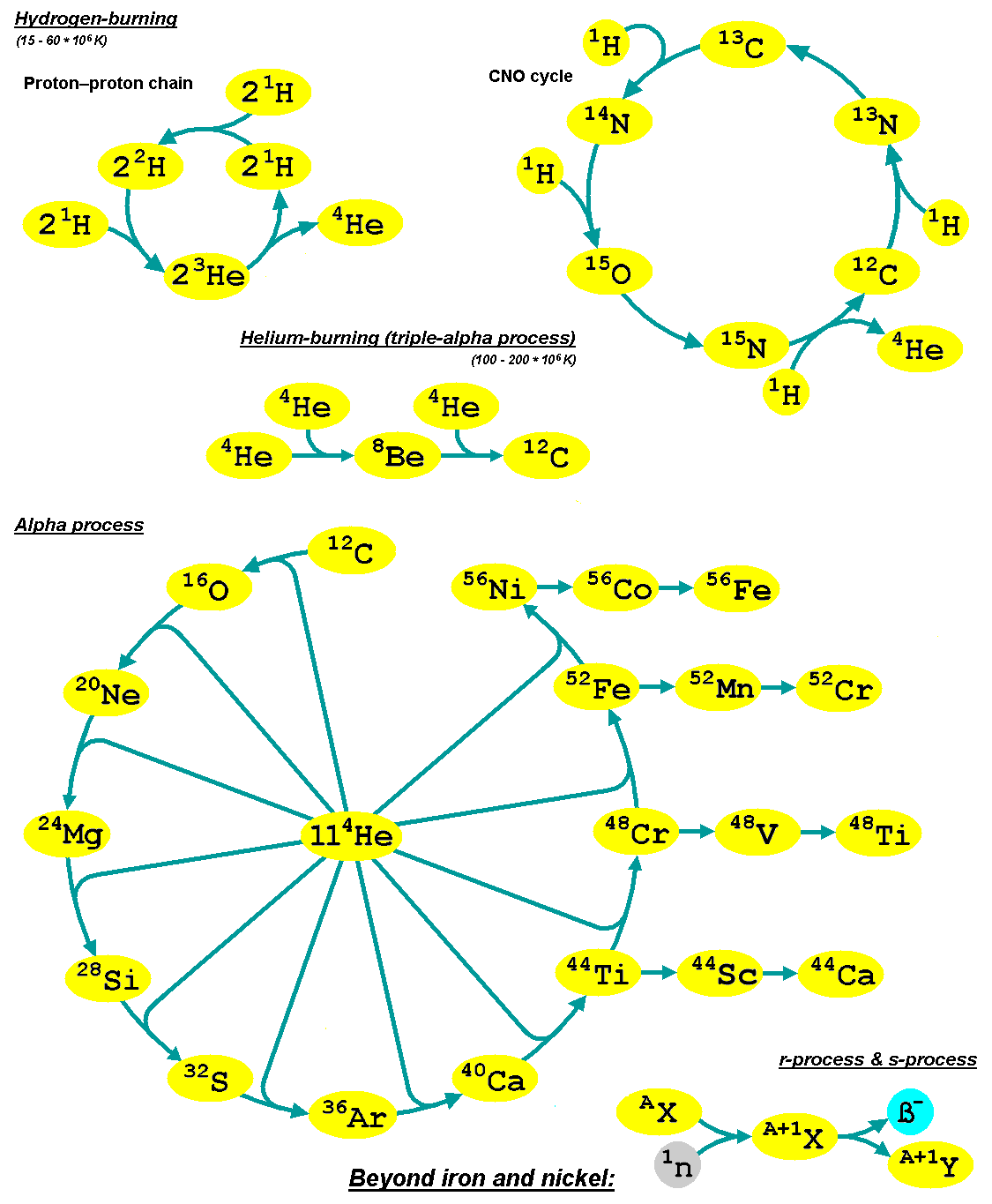

Processes

[edit]There are a number of astrophysical processes which are believed to be responsible for nucleosynthesis. The majority of these occur within stars, and the chain of those nuclear fusion processes are known as hydrogen burning (via the proton–proton chain or the CNO cycle), helium burning, carbon burning, neon burning, oxygen burning and silicon burning. These processes are able to create elements up to and including iron and nickel. This is the region of nucleosynthesis within which the isotopes with the highest binding energy per nucleon are created.

Heavier elements can be assembled within stars by a neutron capture process known as the s-process or in explosive environments, such as supernovae and neutron star mergers, by a number of other processes. Some of those others include the r-process, which involves rapid neutron captures, the rp-process, and the p-process (sometimes known as the gamma process), which results in the photodisintegration of existing nuclei.

Major types

[edit]Big Bang nucleosynthesis

[edit]Big Bang nucleosynthesis[8] occurred within the first three minutes of the beginning of the universe and is responsible for much of the abundance of 1

H (protium), 2

H (D, deuterium), 3

He (helium-3), and 4

He (helium-4). Although 4

He continues to be produced by stellar fusion and alpha decays and trace amounts of 1

H continue to be produced by spallation and certain types of radioactive decay, most of the mass of the isotopes in the universe are thought to have been produced in the Big Bang. The nuclei of these elements, along with some 7

Li and 7

Be are considered to have been formed between 100 and 300 seconds after the Big Bang when the primordial quark–gluon plasma froze out to form protons and neutrons. Because of the very short period in which nucleosynthesis occurred before it was stopped by expansion and cooling (about 20 minutes), no elements heavier than beryllium (or possibly boron) could be formed. Elements formed during this time were in the plasma state, and did not cool to the state of neutral atoms until much later.[citation needed][9]

Stellar nucleosynthesis

[edit]Stellar nucleosynthesis is the nuclear process by which new nuclei are produced. It occurs in stars during stellar evolution. It is responsible for the galactic abundances of elements from carbon to iron. Stars are thermonuclear furnaces in which H and He are fused into heavier nuclei by increasingly high temperatures as the composition of the core evolves.[10] Of particular importance is carbon because its formation from He is a bottleneck in the entire process. Carbon is produced by the triple-alpha process in all stars. Carbon is also the main element that causes the release of free neutrons within stars, giving rise to the s-process, in which the slow absorption of neutrons converts iron into elements heavier than iron and nickel.[11][12]

The products of stellar nucleosynthesis are generally dispersed into the interstellar gas through mass loss episodes and the stellar winds of low mass stars. The mass loss events can be witnessed today in the planetary nebulae phase of low-mass star evolution, and the explosive ending of stars, called supernovae, of those with more than eight times the mass of the Sun.

The first direct proof that nucleosynthesis occurs in stars was the astronomical observation that interstellar gas has become enriched with heavy elements as time passed. As a result, stars that were born from it late in the galaxy, formed with much higher initial heavy element abundances than those that had formed earlier. The detection of technetium in the atmosphere of a red giant star in 1952,[13] by spectroscopy, provided the first evidence of nuclear activity within stars. Because technetium is radioactive, with a half-life much less than the age of the star, its abundance must reflect its recent creation within that star. Equally convincing evidence of the stellar origin of heavy elements is the large overabundances of specific stable elements found in stellar atmospheres of asymptotic giant branch stars. Observation of barium abundances some 20–50 times greater than found in unevolved stars is evidence of the operation of the s-process within such stars. Many modern proofs of stellar nucleosynthesis are provided by the isotopic compositions of stardust, solid grains that have condensed from the gases of individual stars and which have been extracted from meteorites. Stardust is one component of cosmic dust and is frequently called presolar grains. The measured isotopic compositions in stardust grains demonstrate many aspects of nucleosynthesis within the stars from which the grains condensed during the star's late-life mass-loss episodes.[14]

Explosive nucleosynthesis

[edit]Supernova nucleosynthesis occurs in the energetic environment in supernovae, in which the elements between silicon and nickel are synthesized in quasiequilibrium[15] established during fast fusion that attaches by reciprocating balanced nuclear reactions to 28Si. Quasiequilibrium can be thought of as almost equilibrium except for a high abundance of the 28Si nuclei in the feverishly burning mix. This concept[12] was the most important discovery in nucleosynthesis theory of the intermediate-mass elements since Hoyle's 1954 paper because it provided an overarching understanding of the abundant and chemically important elements between silicon (A = 28) and nickel (A = 60). It replaced the incorrect although much cited alpha process of the B2FH paper, which inadvertently obscured Hoyle's 1954 theory.[16] Further nucleosynthesis processes can occur, in particular the r-process (rapid process) described by the B2FH paper and first calculated by Seeger, Fowler and Clayton,[17] in which the most neutron-rich isotopes of elements heavier than nickel are produced by rapid absorption of free neutrons. The creation of free neutrons by electron capture during the rapid compression of the supernova core along with the assembly of some neutron-rich seed nuclei makes the r-process a primary process, and one that can occur even in a star of pure H and He. This is in contrast to the B2FH designation of the process as a secondary process. This promising scenario, though generally supported by supernova experts, has yet to achieve a satisfactory calculation of r-process abundances. The primary r-process has been confirmed by astronomers who had observed old stars born when galactic metallicity was still small, that nonetheless contain their complement of r-process nuclei; thereby demonstrating that the metallicity is a product of an internal process. The r-process is responsible for our natural cohort of radioactive elements, such as uranium and thorium, as well as the most neutron-rich isotopes of each heavy element.

The rp-process (rapid proton) involves the rapid absorption of free protons as well as neutrons, but its role and its existence are less certain.

Explosive nucleosynthesis occurs too rapidly for radioactive decay to decrease the number of neutrons, so that many abundant isotopes with equal and even numbers of protons and neutrons are synthesized by the silicon quasi-equilibrium process.[15] During this process, the burning of oxygen and silicon fuses nuclei that themselves have equal numbers of protons and neutrons to produce nuclides which consist of whole numbers of helium nuclei, up to 15 (representing 60Ni). Such multiple-alpha-particle nuclides are totally stable up to 40Ca (made of 10 helium nuclei), but heavier nuclei with equal and even numbers of protons and neutrons are tightly bound but unstable. The quasi-equilibrium produces radioactive isobars 44Ti, 48Cr, 52Fe, and 56Ni, which (except 44Ti) are created in abundance but decay after the explosion and leave the most stable isotope of the corresponding element at the same atomic weight. The most abundant and extant isotopes of elements produced in this way are 48Ti, 52Cr, and 56Fe. These decays are accompanied by the emission of gamma-rays (radiation from the nucleus), whose spectroscopic lines can be used to identify the isotope created by the decay. The detection of these emission lines were an important early product of gamma-ray astronomy.[18]

The most convincing proof of explosive nucleosynthesis in supernovae occurred in 1987 when those gamma-ray lines were detected emerging from supernova 1987A. Gamma-ray lines identifying 56Co and 57Co nuclei, whose half-lives limit their age to about a year, proved that their radioactive cobalt parents created them. This nuclear astronomy observation was predicted in 1969[18] as a way to confirm explosive nucleosynthesis of the elements, and that prediction played an important role in the planning for NASA's Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory.

Other proofs of explosive nucleosynthesis are found within the stardust grains that condensed within the interiors of supernovae as they expanded and cooled. Stardust grains are one component of cosmic dust. In particular, radioactive 44Ti was measured to be very abundant within supernova stardust grains at the time they condensed during the supernova expansion.[14] This confirmed a 1975 prediction of the identification of supernova stardust (SUNOCONs), which became part of the pantheon of presolar grains. Other unusual isotopic ratios within these grains reveal many specific aspects of explosive nucleosynthesis.

Another type of explosive nucleosynthesis through the r-process was suggested in the flaring of magnetars. Some direct evidence for this was published in 2025. It is estimated that this kind of events has created ~1%–10% of the heavier elements in the universe.[19]

Neutron star mergers

[edit]The merger of binary neutron stars (BNSs) is now believed to be the main source of r-process elements.[20] Being neutron-rich by definition, mergers of this type had been suspected of being a source of such elements, but definitive evidence was difficult to obtain. In 2017 strong evidence emerged, when LIGO, VIRGO, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and INTEGRAL, along with a collaboration of many observatories around the world, detected both gravitational wave and electromagnetic signatures of a likely neutron star merger, GW170817, and subsequently detected signals of numerous heavy elements such as gold as the ejected degenerate matter decays and cools.[21] The first detection of the merger of a neutron star and black hole (NSBHs) came in July 2021 and more after but analysis seem to favor BNSs over NSBHs as the main contributors to heavy metal production.[22][23]

Black hole accretion disk nucleosynthesis

[edit]Nucleosynthesis may happen in accretion disks of black holes.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

Cosmic ray spallation

[edit]Cosmic ray spallation process reduces the atomic weight of interstellar matter by the impact with cosmic rays, to produce some of the lightest elements present in the universe (though not a significant amount of deuterium). Most notably spallation is believed to be responsible for the generation of almost all of 3He and the elements lithium, beryllium, and boron, although some 7

Li and 7

Be are thought to have been produced in the Big Bang. The spallation process results from the impact of cosmic rays (mostly fast protons) against the interstellar medium. These impacts fragment carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen nuclei present. The process results in the light elements beryllium, boron, and lithium in the cosmos at much greater abundances than they are found within solar atmospheres. The quantities of the light elements 1H and 4He produced by spallation are negligible relative to their primordial abundance.

Beryllium and boron are not significantly produced by stellar fusion processes, since 8Be has an extremely short half-life of 8.2×10−17 seconds.[31]

Empirical evidence

[edit]Theories of nucleosynthesis are tested by calculating isotope abundances and comparing those results with observed abundances. Isotope abundances are typically calculated from the transition rates between isotopes in a network. Often these calculations can be simplified as a few key reactions control the rate of other reactions.[citation needed]

Minor mechanisms and processes

[edit]Tiny amounts of certain nuclides are produced on Earth by artificial means. Those are our primary source, for example, of technetium. However, some nuclides are also produced by a number of natural means that have continued after primordial elements were in place. These often act to create new elements in ways that can be used to date rocks or to trace the source of geological processes. Although these processes do not produce the nuclides in abundance, they are assumed to be the entire source of the existing natural supply of those nuclides.

These mechanisms include:

- Radioactive decay may lead to radiogenic daughter nuclides. The nuclear decay of many long-lived primordial isotopes, especially uranium-235, uranium-238, and thorium-232 produce many intermediate daughter nuclides before they too finally decay to isotopes of lead. The Earth's natural supply of elements like radon and polonium is via this mechanism. The atmosphere's supply of argon-40 is due mostly to the radioactive decay of potassium-40 in the time since the formation of the Earth. Little of the atmospheric argon is primordial. Helium-4 is produced by alpha-decay, and the helium trapped in Earth's crust is also mostly non-primordial. In other types of radioactive decay, such as cluster decay, larger species of nuclei are ejected (for example, neon-20), and these eventually become newly formed stable atoms.

- Radioactive decay may lead to spontaneous fission. This is not cluster decay, as the fission products may be split among nearly any type of atom. Thorium-232, uranium-235, and uranium-238 are primordial isotopes that undergo spontaneous fission. Natural technetium and promethium are produced in this manner.

- Nuclear reactions. Naturally occurring nuclear reactions powered by radioactive decay give rise to so-called nucleogenic nuclides. This process happens when an energetic particle from radioactive decay, often an alpha particle, reacts with a nucleus of another atom to change the nucleus into another nuclide. This process may also cause the production of further subatomic particles, such as neutrons. Neutrons can also be produced in spontaneous fission and by neutron emission. These neutrons can then go on to produce other nuclides via neutron-induced fission, or by neutron capture. For example, some stable isotopes such as neon-21 and neon-22 are produced by several routes of nucleogenic synthesis, and thus only part of their abundance is primordial.

- Nuclear reactions due to cosmic rays. By convention, these reaction-products are not termed "nucleogenic" nuclides, but rather cosmogenic nuclides. Cosmic rays continue to produce new elements on Earth by the same cosmogenic processes discussed above that produce primordial beryllium and boron. One important example is carbon-14, produced from nitrogen-14 in the atmosphere by cosmic rays. Iodine-129 is another example.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "DOE Explains...Nucleosynthesis". Energy.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ Eddington, A. S. (1920). "The Internal Constitution of the Stars". The Observatory. 43 (1341): 233–40. Bibcode:1920Obs....43..341E. doi:10.1126/science.52.1341.233. PMID 17747682.

- ^ Eddington, A. S. (1920). "The Internal Constitution of the Stars". Nature. 106 (2653): 14–20. Bibcode:1920Natur.106...14E. doi:10.1038/106014a0. PMID 17747682.

- ^ Actually, before the war ended, he learned about the problem of spherical implosion of plutonium in the Manhattan project. He saw an analogy between the plutonium fission reaction and the newly discovered supernovae, and he was able to show that exploding super novae produced all of the elements in the same proportion as existed on Earth. He felt that he had accidentally fallen into a subject that would make his career. Autobiography William A. Fowler

- ^ Burbidge, E. M.; Burbidge, G. R.; Fowler, W. A.; Hoyle, F. (1957). "Synthesis of the Elements in Stars". Reviews of Modern Physics. 29 (4): 547–650. Bibcode:1957RvMP...29..547B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.29.547.

- ^ Suess, Hans E.; Urey, Harold C. (1956). "Abundances of the Elements". Reviews of Modern Physics. 28 (1): 53–74. Bibcode:1956RvMP...28...53S. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.28.53.

- ^ Stiavelli, Massimo (2009). From First Light to Reionization the End of the Dark Ages. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. p. 8. ISBN 9783527627370.

- ^ Fields, B.D.; Molaro, P.; Sarkar, S. (September 2017). "23. Big-Bang Nucleosynthesis" (PDF). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.729.1183. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-04-01.

- ^ Weinberg, Steven (1993). The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465024377.

- ^ Clayton, D. D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis (Reprint ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Chapter 5. ISBN 978-0-226-10952-7.

- ^ Clayton, D. D.; Fowler, W. A.; Hull, T. E.; Zimmerman, B. A. (1961). "Neutron Capture Chains in Heavy Element Synthesis". Annals of Physics. 12 (3): 331–408. Bibcode:1961AnPhy..12..331C. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(61)90067-7.

- ^ a b Clayton, D. D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis (Reprint ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Chapter 7. ISBN 978-0-226-10952-7.

- ^ Merrill, S. P. W. (1952). "Spectroscopic Observations of Stars of Class". The Astrophysical Journal. 116: 21. Bibcode:1952ApJ...116...21M. doi:10.1086/145589.

- ^ a b Clayton, D. D.; Nittler, L. R. (2004). "Astrophysics with Presolar Stardust". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 42 (1): 39–78. Bibcode:2004ARA&A..42...39C. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.42.053102.134022.

- ^ a b Bodansky, D.; Clayton, D. D.; Fowler, W. A. (1968). "Nuclear Quasi-Equilibrium during Silicon Burning". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 16: 299. Bibcode:1968ApJS...16..299B. doi:10.1086/190176.

- ^ Clayton, D. D. (2007). "Hoyle's Equation". Science. 318 (5858): 1876–1877. doi:10.1126/science.1151167. PMID 18096793. S2CID 118423007.

- ^ Seeger, P. A.; Fowler, W. A.; Clayton, D. D. (1965). "Nucleosynthesis of Heavy Elements by Neutron Capture". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 11: 121. Bibcode:1965ApJS...11..121S. doi:10.1086/190111.

- ^ a b Clayton, D. D.; Colgate, S. A.; Fishman, G. J. (1969). "Gamma-Ray Lines from Young Supernova Remnants". The Astrophysical Journal. 155: 75. Bibcode:1969ApJ...155...75C. doi:10.1086/149849.

- ^ Patel, Anirudh; Metzger, Brian D.; Cehula, Jakub; Burns, Eric; Goldberg, Jared A.; Thompson, Todd A. (April 2025). "Direct Evidence for r-process Nucleosynthesis in Delayed MeV Emission from the SGR 1806–20 Magnetar Giant Flare". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 984 (1): L29. arXiv:2501.09181. Bibcode:2025ApJ...984L..29P. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/adc9b0. ISSN 2041-8205.

- ^ Stromberg, Joseph (16 July 2013). "All the Gold in the Universe Could Come from the Collisions of Neutron Stars". Smithsonian. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ Chu, J. (n.d.). "GW170817 Press Release". LIGO/Caltech. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ^ Chen, Hsin-Yu; Vitale, Salvatore; Foucart, Francois (2021-10-01). "The Relative Contribution to Heavy Metals Production from Binary Neutron Star Mergers and Neutron Star–Black Hole Mergers". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 920 (1): L3. arXiv:2107.02714. Bibcode:2021ApJ...920L...3C. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac26c6. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 238198587.

- ^ "Neutron star collisions are a "goldmine" of heavy elements, study finds". MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 25 October 2021. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- ^ Chakrabarti, S. K.; Jin, L.; Arnett, W. D. (1987). "Nucleosynthesis Inside Thick Accretion Disks Around Black Holes. I – Thermodynamic Conditions and Preliminary Analysis". The Astrophysical Journal. 313: 674. Bibcode:1987ApJ...313..674C. doi:10.1086/165006. OSTI 6468841.

- ^ McLaughlin, G.; Surman, R. (2 April 2007). "Nucleosynthesis from Black Hole Accretion Disks" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-10.

- ^ Frankel, N. (2017). Nucleosynthesis in Accretion Disks Around Black Holes (PDF) (MSc). Lund Observatory/Lund University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-24.

- ^ Surman, R.; McLaughlin, G. C.; Ruffert, M.; Janka, H.-Th.; Hix, W. R. (2008). "Process Nucleosynthesis in Hot Accretion Disk Flows from Black Hole-Neutron Star Mergers". The Astrophysical Journal. 679 (2): L117 – L120. arXiv:0803.1785. Bibcode:2008ApJ...679L.117S. doi:10.1086/589507. S2CID 17114805.

- ^ Arai, K.; Matsuba, R.; Fujimoto, S.; Koike, O.; Hashimoto, M. (2003). "Nucleosynthesis Inside Accretion Disks Around Intermediate-mass Black Holes". Nuclear Physics A. 718: 572–574. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.718..572A. doi:10.1016/S0375-9474(03)00856-X.

- ^ Mukhopadhyay, B. (2018). "Nucleonsynthesis in Advective Accretion Disk Around Compact Object". In Jantzen, R. T.; Ruffini, R.; Gurzadyan, V. G. (eds.). Proceedings of the Ninth Marcel Grossmann Meeting on General Relavitity. World Scientific. pp. 2261–2262. arXiv:astro-ph/0103162. Bibcode:2002nmgm.meet.2261M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.254.7490. doi:10.1142/9789812777386_0544. ISBN 9789812389930. S2CID 118008078.

- ^ Breen, P. G. (2018). "Light element variations in globular clusters via nucleosynthesis in black hole accretion discs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 481 (1): L110–114. arXiv:1804.08877. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.481L.110B. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/sly169. S2CID 54001706.

- ^ Surdoval, Wayne; Berry, David (2021). "A New Approach for Calculating the Alpha-Decay Half-Life for the Heavy and Super-heavy Elements and an Exact A Priori Result for Beyllium-8". osti.gov. U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information. doi:10.2172/1773479. OSTI 1773479. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Hoyle, F. (1946). "The Synthesis of the Elements from Hydrogen". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 106 (5): 343–383. Bibcode:1946MNRAS.106..343H. doi:10.1093/mnras/106.5.343.

- Hoyle, F. (1954). "On Nuclear Reactions Occurring in Very Hot STARS. I. The Synthesis of Elements from Carbon to Nickel". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 1: 121. Bibcode:1954ApJS....1..121H. doi:10.1086/190005.

- Burbidge, E. M.; Burbidge, G. R.; Fowler, W. A.; Hoyle, F. (1957). "Synthesis of the Elements in Stars". Reviews of Modern Physics. 29 (4): 547–650. Bibcode:1957RvMP...29..547B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.29.547.

- Meneguzzi, M.; Audouze, J.; Reeves, H. (1971). "The Production of the Elements Li, Be, B by Galactic Cosmic Rays in Space and Its Relation with Stellar Observations". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 15: 337–359. Bibcode:1971A&A....15..337M.

- Clayton, D. D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis (Reprint ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10952-7.

- Clayton, D. D. (2003). Handbook of Isotopes in the Cosmos. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82381-4.

- Rolfs, C. E.; Rodney, W. S. (2005). Cauldrons in the Cosmos: Nuclear Astrophysics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-72457-7.

- Iliadis, Christian (2015). Nuclear Physics of Stars, 2nd ed. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527692668. ISBN 9783527692668.

- Arcones, A.; Thielemann, F. K. (2022). "Origin of the elements". The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 31 (1): 1. doi:10.1007/s00159-022-00146-x. ISSN 1432-0754.

External links

[edit]- The Valley of Stability (video) – nucleosynthesis explained in terms of the nuclide chart, by CEA (France)

Nucleosynthesis

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Nucleosynthesis is the process by which new atomic nuclei are synthesized from pre-existing protons and neutrons through nuclear reactions, including fusion, fission, and neutron capture.[1][9] This process creates over 100 stable isotopes, ranging from light elements like helium to heavy ones such as uranium, by combining or altering lighter precursors into more complex nuclides.[9][10] Central to this are fundamental particles: protons, which carry a positive charge and define the atomic number , and neutrons, which are neutral and contribute to the nucleus alongside protons.[1] The total number of protons and neutrons in a nucleus determines its atomic mass , where is the neutron number, while isotopes are variants of an element sharing the same but differing in , and nuclides refer to specific combinations of and .[9][10] The scope of nucleosynthesis encompasses the formation of all atomic nuclei except primordial hydrogen, which originated during the Big Bang, and extends to the production of elements up to the heaviest stable isotopes through astrophysical environments.[1][10] Unlike chemical synthesis, which rearranges electrons in atomic orbitals to form molecules, nucleosynthesis operates at the subatomic level, overcoming electrostatic barriers to rearrange protons and neutrons within nuclei.[9] It includes light elements like helium isotopes and traces of lithium from early cosmic conditions, as well as heavier nuclei forged in stellar cores and explosive events, but excludes the initial hydrogen reservoir that serves as fuel for subsequent reactions.[1][10] This process is pivotal to cosmic evolution, as it accounts for the observed abundances of elements throughout the universe, with approximately 2% of galactic hydrogen and helium transformed into heavier species over billions of years.[9] By enriching the interstellar medium with metals—elements beyond helium—these nuclei enable gas cooling that facilitates the collapse and formation of new stars and planetary systems.[9][10] Ultimately, nucleosynthesis provides the raw materials for planetary chemistry and the emergence of life, supplying essential elements like carbon and oxygen that underpin complex molecular structures.[1][9]Nuclear Reactions and Stability

Nucleosynthesis relies on specific nuclear reactions that build heavier elements from lighter ones, primarily through fusion, neutron capture, photodisintegration, and beta decay. Fusion involves the merging of light nuclei to form heavier ones, releasing energy when the binding energy of the product exceeds that of the reactants. A key example is the proton-proton (p-p) chain, where hydrogen nuclei fuse stepwise to produce helium, powering main-sequence stars like the Sun through a series of reactions initiated by the weak interaction overcoming the Coulomb repulsion between protons. Neutron capture occurs when a nucleus absorbs a free neutron, increasing its mass number and potentially leading to unstable isotopes that decay further; this process is crucial for synthesizing elements beyond iron in stellar environments. Photodisintegration, the reverse of radiative capture, happens when high-energy gamma rays break apart nuclei into lighter fragments, such as ejecting a neutron or proton, and acts as a regulatory mechanism in hot astrophysical plasmas by favoring lighter elements under intense radiation. Beta decay, involving the transformation of a neutron into a proton (or vice versa) with the emission of an electron, positron, or electron capture, adjusts the neutron-to-proton ratio in nuclei, enabling the formation of stable isotopes across the periodic table. Nuclear stability is determined by the binding energy, which quantifies the energy required to disassemble a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons. The binding energy for a nucleus with atomic mass number , proton number , neutron mass , proton mass , and atomic mass is given by where is the speed of light; this mass defect reflects the conversion of mass to energy via Einstein's relation. The semi-empirical mass formula approximates the binding energy by incorporating volume, surface, Coulomb, asymmetry, and pairing terms, providing a liquid-drop model analogy for nuclear masses that explains trends in stability across isotopes. Plotting binding energy per nucleon against mass number reveals a curve peaking around iron-56, which has the highest value at approximately 8.8 MeV per nucleon, making it the most stable nucleus because further fusion or fission would require net energy input rather than release. This peak arises from the balance between the attractive strong nuclear force and the repulsive Coulomb force, with heavier elements less bound due to increased proton repulsion and lighter ones due to insufficient strong force cohesion. For reactions to proceed, they must overcome energy thresholds. In fusion, the Coulomb barrier—the electrostatic repulsion between positively charged nuclei—requires kinetic energies on the order of several MeV for light nuclei to tunnel through quantum mechanically and allow the strong force to bind them. The Q-value, defined as the difference in rest mass energy between initial and final states (), determines if a reaction is exoergic (Q > 0, energy-releasing) or endoergic (Q < 0, energy-absorbing); for the latter, an additional threshold energy exceeds |Q| to conserve momentum in the center-of-mass frame.Historical Development

Key Discoveries and Timeline

The foundations of nucleosynthesis research were laid in the 1920s with Edwin Hubble's observation of the universe's expansion. In 1929, Hubble demonstrated a linear relation between the distance and radial velocity of extra-galactic nebulae, establishing the expanding universe model that later underpinned theories of primordial element formation.[11] During the 1930s, key ideas emerged on how stars generate energy via nuclear fusion. In 1937, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker proposed the carbon cycle as a mechanism for hydrogen-to-helium conversion in stars, using carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen as catalysts. Independently, in 1939, Hans Bethe detailed the proton-proton chain and CNO cycle, providing quantitative models for stellar energy production that aligned with observed stellar luminosities. The 1940s brought predictions for primordial nucleosynthesis in the context of the Big Bang. George Gamow, along with Ralph Alpher and Hans Bethe, argued in 1948 that the early universe's high temperatures would enable rapid neutron capture and fusion, producing primarily hydrogen and helium, with traces of deuterium, helium-3, and lithium-7. The 1950s marked a breakthrough in stellar nucleosynthesis theory and specific predictions. The influential B²FH paper, published in 1957 by Margaret Burbidge, Geoffrey Burbidge, William Fowler, and Fred Hoyle, synthesized observational data and nuclear physics to explain the production of elements heavier than helium in stars through processes like slow and rapid neutron capture (s- and r-processes), alpha capture, and explosive burning. In 1954, Hoyle predicted a resonant excited state in carbon-12 at approximately 7.65 MeV to enhance the triple-alpha process, enabling efficient carbon production in stars; this Hoyle state was experimentally verified in 1957. Observations in the late 1950s also provided evidence for cosmic ray spallation as a source of light elements, with balloon experiments detecting lithium, beryllium, and boron nuclei in primary cosmic rays at abundances consistent with fragmentation of heavier cosmic ray particles on interstellar matter.[12] In the 1960s, empirical support for Big Bang nucleosynthesis grew through measurements of primordial helium. Early spectroscopic observations of extragalactic H II regions, such as those in the Magellanic Clouds and nearby galaxies, yielded helium-to-hydrogen mass ratios around 0.25, matching theoretical predictions and distinguishing primordial abundances from stellar pollution. The 1970s saw refined identification of the r-process through stellar spectroscopy. Abundance patterns in metal-poor halo stars revealed enhancements in r-process elements (e.g., europium relative to iron) that could not be explained by the s-process alone, confirming rapid neutron capture as a distinct pathway for heavy nuclei beyond the iron peak. A pivotal observational milestone occurred in 2017 with the detection of the neutron star merger GW170817. Gravitational wave signals from LIGO/Virgo, combined with electromagnetic follow-up revealing a kilonova rich in r-process signatures, confirmed mergers as major sites for synthesizing heavy elements like strontium, gold, and platinum, with ejecta masses producing up to 5-10 Earth masses of such material. In the 2020s, the James Webb Space Telescope has enabled direct probes of early chemical evolution. Observations in 2023 of galaxies at redshifts z ≈ 7-9 (corresponding to 500-700 million years post-Big Bang) revealed oxygen abundances rising rapidly from near-primordial levels to about 10-20% of solar values, indicating swift metal enrichment from the first generations of massive stars. In 2024, scientists proposed the νr-process, a neutrino-driven variant of rapid neutron capture in explosive astrophysical sites. JWST data in 2025 further detailed iron abundances in galaxies at z=9-12, reinforcing models of rapid early universe metal enrichment.[13][14]Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical foundations of nucleosynthesis began in the 1940s with George Gamow's development of models for the production of light elements during the early hot phase of the universe, incorporating alpha-particle capture, beta decay, and gamma emission as key nuclear processes to explain the observed abundances of hydrogen, helium, and trace amounts of lithium and beryllium. These ideas, formalized in the 1948 αβγ paper co-authored with Ralph Alpher and Hans Bethe, laid the groundwork for Big Bang nucleosynthesis by predicting element formation through rapid neutron capture and subsequent decays in a cooling plasma. However, Fred Hoyle challenged these primordial models in 1946 by emphasizing stellar interiors as the primary sites for element synthesis, arguing within the steady-state cosmological framework that continuous matter creation necessitated ongoing nuclear processing in stars to account for heavier elements beyond helium. A major advancement came in 1957 with the B²FH paper by Margaret Burbidge, Geoffrey Burbidge, William Fowler, and Fred Hoyle, which systematically outlined stellar nucleosynthesis pathways for elements heavier than iron through distinct nuclear capture processes. The framework introduced the s-process, involving slow neutron capture followed by beta decay in asymptotic giant branch stars; the r-process, characterized by rapid neutron capture in high-density environments like supernovae; and the p-process, a proton capture mechanism producing proton-rich isotopes in explosive stellar layers. This synthesis resolved long-standing puzzles in isotopic abundances by linking specific astrophysical sites to nuclear reaction networks, establishing a predictive basis for cosmic element distribution. In the 1970s, theoretical models expanded to incorporate explosive nucleosynthesis yields from core-collapse supernovae, with W. David Arnett's calculations demonstrating how shock-heated ejecta could drive rapid proton and neutron captures to produce intermediate-mass elements like silicon and sulfur. By the 2000s, multidimensional hydrodynamic simulations revolutionized the field, enabling detailed modeling of convective mixing and turbulent transport in stellar interiors, which refined yield predictions for massive stars and accounted for asymmetries in supernova explosions.[15] Following the 2017 detection of the binary neutron star merger GW170817, post-merger models integrated kilonova emissions into nucleosynthesis frameworks, confirming r-process dominance in neutron-rich ejecta and linking merger remnants to the production of lanthanides and actinides. Contemporary challenges in nucleosynthesis theory center on galactic chemical evolution models, which struggle to reconcile predicted yields from various sites—such as supernovae, asymptotic giant branch stars, and mergers—with observed abundance patterns, particularly for neutron-capture elements that require fine-tuned star formation histories and inflow rates.[16] These models highlight discrepancies in reproducing radial gradients and time-dependent enrichment, underscoring the need for coupled hydrodynamic and nuclear reaction simulations to tie specific production sites to galactic-scale abundances.[16]Primordial Nucleosynthesis

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis Mechanism

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) takes place in the early universe approximately 1 to 20 minutes after the Big Bang, when the temperature has cooled to between K and K, allowing the formation of light atomic nuclei from protons and neutrons while the universe is still dense and hot enough for nuclear reactions to occur.[17] At this stage, the weak interactions that interconvert neutrons and protons have already frozen out around 1 second after the Big Bang, fixing the neutron-to-proton ratio at about 1/6, which sets the initial conditions for subsequent fusion processes.[18] The expansion and cooling of the universe drive the reaction dynamics, with nuclear statistical equilibrium holding briefly before rates drop due to decreasing density. The baryon-to-photon ratio, , is a crucial parameter that governs the freeze-out of reactions and the final light element yields, as it reflects the relative scarcity of baryons compared to photons, which influences photodissociation rates.[19] This low creates a significant challenge known as the deuterium bottleneck: although deuterium (H) has a relatively low binding energy of 2.2 MeV, the high photon-to-baryon ratio () populates the high-energy tail of the photon spectrum, efficiently photodissociating any deuterium formed until the temperature drops to around 0.1 MeV ( K).[20] The Saha equation describes the equilibrium abundance of deuterium in this phase: where are the number densities of deuterium, protons, and neutrons, are their masses, is the deuterium binding energy, is Boltzmann's constant, is temperature, and is Planck's constant; this equation quantifies how the bottleneck delays BBN until the destruction rate falls below the production rate, approximately when .[20] Once the deuterium bottleneck is overcome around 100–200 seconds after the Big Bang, rapid fusion ensues via a chain of two-body reactions due to the low density. The primary sequence begins with the radiative capture He, where deuterium fuses with a proton to form He, followed by He(He, 2p)^4)He, which efficiently produces most of the He since nearly all available neutrons are incorporated into this stable nucleus.[21] Trace amounts of Li and Be form through branches such as He()^7)Be and H()^7)Li, where He and H (tritium) arises from H; Be later decays to Li on timescales longer than BBN.[17] Reaction rates are determined by thermal averages of cross-sections, , where is the velocity-dependent cross-section and is the relative velocity, integrated over the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution; these rates dictate the progression from equilibrium to non-equilibrium freeze-out as the universe expands.[20] BBN ceases around 20 minutes when the temperature reaches K, as reaction rates become too slow compared to the expansion rate.[18] The process is limited to elements up to lithium because there are no stable nuclei with mass numbers 5 or 8, creating gaps that prevent further fusion chains; the rapid expansion dilutes the density before heavier elements can form in significant amounts.[17]Primordial Element Abundances

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) predicts the primordial abundances of the lightest elements, which serve as key probes of early universe conditions. These predictions depend sensitively on the baryon-to-photon ratio , fixed by cosmic microwave background (CMB) measurements at from Planck 2018 data.[22] Standard BBN calculations, incorporating updated nuclear reaction rates and the neutron lifetime s, yield a primordial helium-4 mass fraction , deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio D/H , helium-3-to-hydrogen ratio He/H , and lithium-7-to-hydrogen ratio Li/H .[23][24] These values reflect the freeze-out of weak interactions and subsequent nuclear capture processes in the first few minutes after the Big Bang.| Element Ratio | BBN Prediction | Primary Observation Method | Observed Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (^4He mass fraction) | 0.247 | He I emission lines in low-metallicity H II regions | 0.245 ± 0.003[23][25] |

| D/H | Absorption lines in quasar spectra | [23][26] | |

| He/H | Emission lines in H II regions and planetary nebulae | (upper limit, affected by stellar evolution)[23] | |

| Li/H | Absorption lines in metal-poor halo star spectra | [23][27] |

Stellar and Explosive Nucleosynthesis

Hydrogen and Helium Burning in Stars

Hydrogen burning in stars primarily converts hydrogen into helium through nuclear fusion reactions occurring in the cores of main-sequence stars. In low-mass stars, such as the Sun, the dominant process is the proton-proton (pp) chain, which initiates with the fusion of two protons to form a deuteron, a positron, and a neutrino:This step is followed by subsequent reactions involving the deuteron capturing another proton to form helium-3, and eventually two helium-3 nuclei fusing to produce helium-4, releasing two protons:

The net result of the pp chain is the conversion of four protons into one helium-4 nucleus, releasing energy primarily through gamma rays and neutrinos, with the process being highly temperature-sensitive due to the weak interaction in the initial step. In more massive stars, where core temperatures exceed approximately 15 million Kelvin, the CNO (carbon-nitrogen-oxygen) cycle becomes the primary mechanism for hydrogen fusion. This catalytic cycle uses carbon-12 as a seed nucleus, which captures a proton to form nitrogen-13:

followed by a series of beta decays and proton captures that cycle through nitrogen and oxygen isotopes, ultimately regenerating carbon-12 and producing helium-4. The full cycle net reaction is

with the rate strongly depending on temperature because higher temperatures favor the proton capture steps over competing reactions. Unlike the pp chain, the CNO cycle is more efficient in energy production per reaction but requires trace amounts of CNO elements as catalysts. Following the exhaustion of core hydrogen, stars ascend the red giant branch, where helium burning ignites in the degenerate core of low- to intermediate-mass stars or in the non-degenerate core of massive stars shortly after core hydrogen exhaustion. The primary reaction is the triple-alpha process, in which two helium-4 nuclei first form an unstable beryllium-8 intermediate, which then captures a third helium-4 to produce carbon-12 plus a gamma ray:

3\, ^4\mathrm{He \to ^{12}C + \gamma}.

This process is greatly enhanced by the resonance in the excited Hoyle state of carbon-12 at 7.65 MeV, which lowers the effective Coulomb barrier and increases the reaction rate by orders of magnitude at stellar temperatures around 100 million Kelvin. Without this resonance, carbon production would be insufficient to explain observed abundances. Subsequent alpha-particle captures during helium burning extend the chain, with carbon-12 capturing another helium-4 to form oxygen-16 via

though this reaction competes with further carbon production. The yields from helium burning predominantly produce helium-4 as a byproduct from earlier stages, but the core synthesis results in comparable amounts of carbon-12 and oxygen-16, with the C/O ratio typically around 0.5 to 3 depending on stellar mass and metallicity; trace amounts of neon-20 and magnesium-24 arise from minor branches. These light elements form the building blocks for further nucleosynthesis in more advanced stellar phases.[30]

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{ll}{\mathrm {n} {\vphantom {A}}^{0}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}{}+{}\mathrm {e} {\vphantom {A}}^{-}{}+{}{\overline {\nu }}{\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{e}}}&{\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}{}+{}\mathrm {n} {\vphantom {A}}^{0}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}+{}\mathrm {\gamma } }\\{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}+{}\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {\gamma } }&{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {n} {\vphantom {A}}^{0}}\\{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {T} {}+{}\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}&{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {T} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {n} {\vphantom {A}}^{0}}\\{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {T} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {3}}^{\hphantom {7}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{3}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {7}}}\mathrm {Li} {}+{}\mathrm {\gamma } }&{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {n} {\vphantom {A}}^{0}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {T} {}+{}\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}\\{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {1}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{1}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {D} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}&{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {4}}^{\hphantom {7}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{4}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {7}}}\mathrm {Be} {}+{}\mathrm {\gamma } }\\{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {3}}^{\hphantom {7}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{3}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {7}}}\mathrm {Li} {}+{}\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {2}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{2}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} }&{{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {4}}^{\hphantom {7}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{4}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {7}}}\mathrm {Be} {}+{}\mathrm {n} {\vphantom {A}}^{0}{}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {3}}^{\hphantom {7}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{3}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {7}}}\mathrm {Li} {}+{}\mathrm {p} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}}\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d098974113b455bfa76e746d4449feeecb729b6)