Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

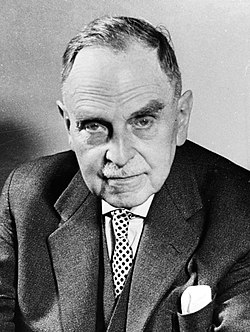

Otto Hahn

View on Wikipedia

Otto Hahn (German: [ˈɔtoː ˈhaːn] ⓘ; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the field of radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and discoverer of nuclear fission, the science behind nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons. Hahn and Lise Meitner discovered isotopes of the radioactive elements radium, thorium, protactinium and uranium. He also discovered the phenomena of atomic recoil and nuclear isomerism, and pioneered rubidium–strontium dating. In 1938, Hahn, Meitner and Fritz Strassmann discovered nuclear fission, for which Hahn alone was awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Key Information

A graduate of the University of Marburg, which awarded him a doctorate in 1901, Hahn studied under Sir William Ramsay at University College London and at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, under Ernest Rutherford, where he discovered several new radioactive isotopes. He returned to Germany in 1906; Emil Fischer let him use a former woodworking shop in the basement of the Chemical Institute at the University of Berlin as a laboratory. Hahn completed his habilitation in early 1907 and became a Privatdozent. In 1912, he became head of the Radioactivity Department of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (KWIC). Working with Austrian physicist Lise Meitner in the building that now bears their names, they made a series of groundbreaking discoveries, culminating with her isolation of the longest-lived isotope of protactinium in 1918.

During World War I Hahn served with a Landwehr regiment on the Western Front, and with the chemical warfare unit headed by Fritz Haber on the Western, Eastern and Italian fronts, earning the Iron Cross (2nd Class) for his part in the First Battle of Ypres. After the war he became the head of the KWIC, while remaining in charge of his own department. Between 1934 and 1938, he worked with Strassmann and Meitner on the study of isotopes created by neutron bombardment of uranium and thorium, which led to the discovery of nuclear fission. He was an opponent of Nazism and the persecution of Jews by the Nazi Party that caused the removal of many of his colleagues, including Meitner, who was forced to flee Germany in 1938. Nonetheless, during World War II, he worked on the German nuclear weapons program, cataloguing the fission products of uranium. At the end of the war he was arrested by the Allied forces and detained in Farm Hall with nine other German scientists, from July 1945 to January 1946.

Hahn served as the last president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science in 1946 and as the founding president of its successor, the Max Planck Society from 1948 to 1960. In 1959, he co-founded the Federation of German Scientists, a non-governmental organisation committed to the ideal of responsible science. As he worked to rebuild German science, he became one of the most influential and respected citizens of post-war West Germany.

Early life and education

[edit]Otto Hahn was born in Frankfurt am Main on 8 March 1879, the youngest son of Heinrich Hahn, a prosperous glazier and founder of the Glasbau Hahn company, and Charlotte Hahn (née Giese). He had an older half-brother Karl, his mother's son from her previous marriage, and two older brothers, Heiner and Julius. The family lived above his father's workshop. The younger three boys were educated at the Klinger Oberrealschule in Frankfurt. At the age of 15, Otto began to take a special interest in chemistry, and carried out simple experiments in the laundry room of the family home. His father wanted him to study architecture, as he had built or acquired several residential and business properties, but Otto persuaded him that his ambition was to become an industrial chemist.[1]

In 1897, after passing his Abitur, Hahn began to study chemistry at the University of Marburg. His subsidiary subjects were mathematics, physics, mineralogy and philosophy. Hahn joined the Students' Association of Natural Sciences and Medicine, a student fraternity and a forerunner of today's Landsmannschaft Nibelungi (Coburger Convent der akademischen Landsmannschaften und Turnerschaften). He spent his third and fourth semesters at the University of Munich, studying organic chemistry under Adolf von Baeyer, physical chemistry under Wilhelm Muthmann, and inorganic chemistry under Karl Andreas Hofmann. In 1901, Hahn received his doctorate in Marburg for a dissertation entitled "On Bromine Derivates of Isoeugenol", a topic in classical organic chemistry. He completed his one-year military service (instead of the usual two because he had a doctorate) in the 81st Infantry Regiment, but unlike his brothers, did not apply for a commission. He then returned to the University of Marburg, where he worked for two years as assistant to his doctoral supervisor, Geheimrat professor Theodor Zincke.[2][3]

Early career in London and Canada

[edit]Discovery of radiothorium and other "new elements"

[edit]

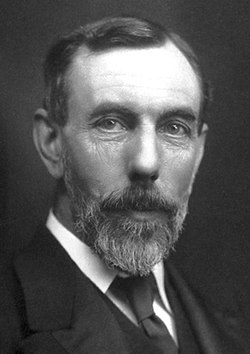

Hahn's intention was still to work in industry. He received an offer of employment from Eugen Fischer, the director of Kalle & Co. (and the father of organic chemist Hans Fischer), but a condition of employment was that Hahn had to have lived in another country and have a reasonable command of another language. With this in mind, and to improve his knowledge of English, Hahn took up a post at University College London in 1904, working under Sir William Ramsay, who was known for having discovered the noble gases. Here Hahn worked on radiochemistry, at that time a very new field. In early 1905, in the course of his work with salts of radium, Hahn discovered a new substance he called radiothorium (thorium-228), which at that time was believed to be a new radioactive element.[2] In fact, it was an isotope of the known element thorium; the concept of an isotope, along with the term, was coined in 1913 by the British chemist Frederick Soddy.[4]

Ramsay was enthusiastic when yet another new element was found in his institute, and he intended to announce the discovery in a correspondingly suitable way. In accordance with tradition this was done before the committee of the venerable Royal Society. At the session of the Royal Society on 16 March 1905 Ramsay communicated Hahn's discovery of radiothorium.[5] The Daily Telegraph informed its readers:

Very soon the scientific papers will be agog with a new discovery which has been added to the many brilliant triumphs of Gower Street. Dr. Otto Hahn, who is working at University College, has discovered a new radioactive element, extracted from a mineral from Ceylon, named Thorianite, and possibly, it is conjectured, the substance which renders thorium radioactive. Its activity is at least 250,000 times as great as that of thorium, weight for weight. It gives off a gas (generally called an emanation), identical with the radioactive emanation from thorium. Another theory of deep interest is that it is the possible source of a radioactive element possibly stronger in radioactivity than radium itself, and capable of producing all the curious effects which are known of radium up to the present. – The discoverer read a paper on the subject to the Royal Society last week, and this should rank, when published, among the most original of recent contributions to scientific literature.[6]

Hahn published his results in the Proceedings of the Royal Society on 24 May 1905.[7] It was the first of more than 250 scientific publications in the field of radiochemistry.[8] At the end of his time in London, Ramsay asked Hahn about his plans for the future, and Hahn told him about the job offer from Kalle & Co. Ramsay told him radiochemistry had a bright future, and that someone who had discovered a new radioactive element should go to the University of Berlin. Ramsay wrote to Emil Fischer, the head of the chemistry institute there, who replied that Hahn could work in his laboratory, but could not be a Privatdozent because radiochemistry was not taught there. At this point, Hahn decided that he first needed to know more about the subject, so he wrote to the leading expert on the field, Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford agreed to take Hahn on as an assistant, and Hahn's parents undertook to pay Hahn's expenses.[9]

From September 1905 until mid-1906, Hahn worked with Rutherford's group in the basement of the Macdonald Physics Building at McGill University in Montreal. There was some scepticism about the existence of radiothorium, which Bertram Boltwood memorably described as a compound of thorium X and stupidity. Boltwood was soon convinced that it did exist, although he and Hahn differed on what its half-life was. William Henry Bragg and Richard Kleeman had noted that the alpha particles emitted from radioactive substances always had the same energy, providing a second way of identifying them, so Hahn set about measuring the alpha particle emissions of radiothorium. In the process, he found that a precipitation of thorium A (polonium-216) and thorium B (lead-212) also contained a short-lived "element", which he named thorium C (which was later identified as polonium-212). Hahn was unable to separate it, and concluded that it had a very short half-life (it is about 300 ns). He also identified radioactinium (thorium-227) and radium D (later identified as lead-210).[10][11] Rutherford remarked that: "Hahn has a special nose for discovering new elements."[12]

Chemical Institute in Berlin

[edit]Discovery of mesothorium I

[edit]

In 1906, Hahn returned to Germany, where Fischer placed at his disposal a former woodworking shop (Holzwerkstatt) in the basement of the Chemical Institute to use as a laboratory. Hahn equipped it with electroscopes to measure alpha and beta particles and gamma rays. In Montreal these had been made from discarded coffee tins; Hahn made the ones in Berlin from brass, with aluminium strips insulated with amber. These were charged with hard rubber sticks that he rubbed against the sleeves of his suit.[14] It was not possible to conduct research in the wood shop, but Alfred Stock, the head of the inorganic chemistry department, let Hahn use a space in one of his two private laboratories.[15] Hahn purchased two milligrams of radium from Friedrich Oskar Giesel, the discoverer of emanium (radon), for 100 marks a milligram (equivalent to €700 in 2021),[14] and obtained thorium for free from Otto Knöfler, whose Berlin firm was a major producer of thorium products.[16]

In the space of a few months Hahn discovered mesothorium I (radium-228), mesothorium II (actinium-228), and – independently from Boltwood – the mother substance of radium, ionium (later identified as thorium-230). In subsequent years, mesothorium I assumed great importance because, like radium-226 (discovered by Pierre and Marie Curie), it was ideally suited for use in medical radiation treatment, but cost only half as much to manufacture. Along the way, Hahn determined that just as he was unable to separate thorium from radiothorium, so he could not separate mesothorium I from radium.[17][18]

In Canada there had been no requirement to be circumspect when addressing the egalitarian New Zealander Rutherford, but many people in Germany found his manner off-putting, and characterised him as an "Anglicised Berliner".[19] Hahn completed his habilitation in early 1907, and became a Privatdozent. A thesis was not required; the Chemical Institute accepted one of his publications on radioactivity instead.[20] Most of the organic chemists at the Chemical Institute did not regard Hahn's work as real chemistry.[21] Fischer objected to Hahn's contention in his habilitation colloquium that many radioactive substances existed in such tiny amounts that they could only be detected by their radioactivity, venturing that he had always been able to detect substances with his keen sense of smell, but soon gave in.[15] One department head remarked: "it is incredible what one gets to be a Privatdozent these days!"[21]

Physicists were more accepting of Hahn's work, and he began attending a colloquium at the Physics Institute conducted by Heinrich Rubens. It was at one of these colloquia where, on 28 September 1907, he made the acquaintance of the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner. Almost the same age as himself, she was only the second woman to receive a doctorate from the University of Vienna, and had already published two papers on radioactivity. Rubens suggested her as a possible collaborator. So began the thirty-year collaboration and lifelong close friendship between the two scientists.[21][22]

In Montreal, Hahn had worked with physicists including at least one woman, Harriet Brooks, but it was difficult for Meitner at first. Women were not yet admitted to universities in Prussia. Meitner was allowed to work in the wood shop, which had its own external entrance, but could not enter the rest of the institute, including Hahn's laboratory space upstairs. If she wanted to go to the toilet, she had to use one at the restaurant down the street. The following year, women were admitted to universities, and Fischer lifted the restrictions and had women's toilets installed in the building.[23]

Discovery of radioactive recoil

[edit]Harriet Brooks observed a radioactive recoil in 1904, but interpreted it wrongly. Hahn and Meitner succeeded in demonstrating the radioactive recoil incident to alpha particle emission and interpreted it correctly. Hahn pursued a report by Stefan Meyer and Egon Schweidler of a decay product of actinium with a half-life of about 11.8 days. Hahn determined that it was actinium X (radium-223). He also discovered that at the moment when a radioactinium (thorium-227) atom emits an alpha particle, it does so with great force, and the actinium X experiences a recoil. This is enough to free it from chemical bonds, and it has a positive charge, and can be collected at a negative electrode.[24]

Hahn was thinking only of actinium, but on reading his paper, Meitner told him that he had found a new way of detecting radioactive substances. They set up some tests, and soon found actinium C'' (thallium-207) and thorium C'' (thallium-208).[24] The physicist Walther Gerlach described radioactive recoil as "a profoundly significant discovery in physics with far-reaching consequences".[25]

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry

[edit]

In 1910, Hahn was appointed professor by the Prussian Minister of Culture and Education, August von Trott zu Solz. Two years later, Hahn became head of the Radioactivity Department of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (KWIC) in Berlin-Dahlem (in what is today the Hahn-Meitner-Building of the Free University of Berlin). This came with an annual salary of 5,000 marks (equivalent to €29,000 in 2021). In addition, he received 66,000 marks in 1914 (equivalent to €369,000 in 2021) from Knöfler for the mesothorium process, of which he gave 10 per cent to Meitner. The new institute was inaugurated on 23 October 1912 in a ceremony presided over by Kaiser Wilhelm II.[28] The Kaiser was shown glowing radioactive substances in a dark room.[29]

The move to new accommodation was fortuitous, as the wood shop had become heavily contaminated by radioactive liquids that had been spilt, and radioactive gases that had vented and then decayed and settled as radioactive dust, making sensitive measurements impossible. To ensure that their clean new laboratories stayed that way, Hahn and Meitner instituted strict procedures. Chemical and physical measurements were conducted in different rooms, people handling radioactive substances had to follow protocols that included not shaking hands, and rolls of toilet paper were hung next to every telephone and door handle. Strongly radioactive substances were stored in the old wood shop, and later in a purpose-built radium house on the institute grounds.[30]

World War I

[edit]In July 1914—shortly before the outbreak of World War I—Hahn was recalled to active duty with the army in a Landwehr regiment. They marched through Belgium, where the platoon he commanded was armed with captured machine guns. He was awarded the Iron Cross (2nd Class) for his part in the First Battle of Ypres. He was a joyful participant in the Christmas truce of 1914, and was commissioned as a lieutenant.[31] In mid-January 1915, he was summoned to meet chemist Fritz Haber, who explained his plan to break the trench deadlock with chlorine gas. Hahn raised the issue that the Hague Convention banned the use of projectiles containing poison gases, but Haber explained that the French had already initiated chemical warfare with tear gas grenades, and he planned to get around the letter of the convention by releasing gas from cylinders instead of shells.[32]

Haber's new unit was called Pioneer Regiment 35. After brief training in Berlin, Hahn, together with physicists James Franck and Gustav Hertz, was sent to Flanders again to scout for a site for a first gas attack. He did not witness the attack because he and Franck were off selecting a position for the next attack. Transferred to Poland, at the Battle of Bolimów on 12 June 1915, they released a mixture of chlorine and phosgene gas. Some German troops were reluctant to advance when the gas started to blow back, so Hahn led them across No Man's land. He witnessed the death agonies of Russians they had poisoned, and unsuccessfully attempted to revive some with gas masks. On their next attempt on 7 July, the gas again blew back on German lines, and Hertz was poisoned. This assignment was interrupted by a mission at the front in Flanders and again in 1916 by a mission to Verdun to introduce shells filled with phosgene to the Western Front. Then once again he was hunting along both fronts for sites for gas attacks. In December 1916 he joined the new gas command unit at Imperial Headquarters.[32][33]

Between operations, Hahn returned to Berlin, where he was able to slip back to his old laboratory and work with Meitner, continuing with their research. In September 1917 he was one of three officers, disguised in Austrian uniforms, sent to the Isonzo front in Italy to find a suitable location for an attack, using newly developed rifled minenwerfers that simultaneously hurled hundreds of containers of poison gas onto enemy targets. They selected a site where the Italian trenches were sheltered in a deep valley so that a gas cloud would persist. The following Battle of Caporetto broke the Italian lines, and the Central Powers overran much of northern Italy. That summer Hahn was accidentally poisoned by phosgene while testing a new model of gas mask. At the end of the war he was in the field in mufti on a secret mission to test a pot that heated and released a cloud of arsenicals.[34][32]

Discovery of protactinium

[edit]

In 1913, chemists Frederick Soddy and Kasimir Fajans independently observed that alpha decay caused atoms to move down two places on the periodic table, while the loss of two beta particles restored it to its original position. Under the resulting reorganisation of the periodic table, radium was placed in group II, actinium in group III, thorium in group IV and uranium in group VI. This left a gap between thorium and uranium. Soddy predicted that this unknown element, which he referred to (after Dmitri Mendeleev) as "ekatantalium", would be an alpha emitter with chemical properties similar to tantalum. It was not long before Fajans and Oswald Helmuth Göhring discovered it as a decay product of a beta-emitting product of thorium. Based on the radioactive displacement law of Fajans and Soddy, this was an isotope of the missing element, which they named "brevium" after its short half-life. However, it was a beta emitter, and therefore could not be the mother isotope of actinium. This had to be another isotope of the same element.[35]

Hahn and Meitner set out to find the missing mother isotope. They developed a new technique for separating the tantalum group from pitchblende, which they hoped would speed the isolation of the new isotope. The work was interrupted by the First World War. Meitner became an X-ray nurse, working in Austrian Army hospitals, but she returned to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in October 1916. Hahn joined the new gas command unit at Imperial Headquarters in Berlin in December 1916 after travelling between the western and eastern front, Berlin and Leverkusen between mid-1914 and late 1916.[33]

Most of the students, laboratory assistants and technicians had been called up, so Hahn, who was stationed in Berlin between January and September 1917,[36] and Meitner had to do everything themselves. By December 1917 she was able to isolate the substance, and after further work were able to prove that it was indeed the missing isotope. Meitner submitted her and Hahn's findings for publication in March 1918 to the scientific paper Physikalischen Zeitschrift under the title Die Muttersubstanz des Actiniums; Ein Neues Radioaktives Element von Langer Lebensdauer ("The Mother Substance of Actinium; A New Radioactive Element with a Long Lifetime").[35][37] Although Fajans and Göhring had been the first to discover the element, custom required that an element was represented by its longest-lived and most abundant isotope, and while brevium had a half-life of 1.7 minutes, Hahn and Meitner's isotope had one of 32,500 years. The name brevium no longer seemed appropriate. Fajans agreed to Meitner and Hahn naming the element "protoactinium".[38][39]

In June 1918, Soddy and John Cranston announced that they had extracted a sample of the isotope, but unlike Hahn and Meitner were unable to describe its characteristics. They acknowledged Hahn´s and Meitner's priority, and agreed to the name.[39] The connection to uranium remained a mystery, as neither of the known isotopes of uranium decayed into protactinium. It remained unsolved until the mother isotope, uranium-235, was discovered in 1929.[35][37] For their discovery Hahn and Meitner were repeatedly nominated for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in the 1920s by several scientists, among them Max Planck, Heinrich Goldschmidt, and Fajans himself.[40][41] In 1949, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) named the new element definitively protactinium, and confirmed Hahn and Meitner as discoverers.[42]

Discovery of nuclear isomerism

[edit]

With the discovery of protactinium, most of the decay chains of uranium had been mapped. When Hahn returned to his work after the war, he looked back over his 1914 results, and considered some anomalies that had been dismissed or overlooked. He dissolved uranium salts in a hydrofluoric acid solution with tantalic acid. First the tantalum in the ore was precipitated, then the protactinium. In addition to the uranium X1 (thorium-234) and uranium X2 (protactinium-234), Hahn detected traces of a radioactive substance with a half-life of between 6 and 7 hours. There was one isotope known to have a half-life of 6.2 hours, mesothorium II (actinium-228). This was not in any probable decay chain, but it could have been contamination, as the KWIC had experimented with it. Hahn and Meitner demonstrated in 1919 that when actinium is treated with hydrofluoric acid, it remains in the insoluble residue. Since mesothorium II was an isotope of actinium, the substance was not mesothorium II; it was protactinium.[43][44] Hahn was now confident enough he had found something that he named his new isotope "uranium Z". In February 1921, he published the first report on his discovery.[45]

Hahn determined that uranium Z had a half-life of around 6.7 hours (with a two per cent margin of error) and that when uranium X1 decayed, it became uranium X2 about 99.75 per cent of the time, and uranium Z around 0.25 per cent of the time. He found that the proportion of uranium X to uranium Z extracted from several kilograms of uranyl nitrate remained constant over time, strongly indicating that uranium X was the mother of uranium Z. To prove this, Hahn obtained a hundred kilograms of uranyl nitrate; separating the uranium X from it took weeks. He found that the half-life of the parent of uranium Z differed from the known 24-day half-life of uranium X1 by no more than two or three days, but was unable to get a more accurate value. Hahn concluded that uranium Z and uranium X2 were both the same isotope of protactinium (protactinium-234), and they both decayed into uranium II (uranium-234), but with different half-lives.[43][44][46]

Uranium Z was the first example of nuclear isomerism. Walther Gerlach later remarked that this was "a discovery that was not understood at the time but later became highly significant for nuclear physics".[25] Not until 1936 was Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker able to provide a theoretical explanation of the phenomenon.[47][48] For this discovery, whose full significance was recognised by very few, Hahn was again proposed for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry by Bernhard Naunyn, Goldschmidt and Planck.[40]

Applied Radiochemistry

[edit]As a young graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley in the mid-1930s and in connection with our work with plutonium a few years later, I used his book Applied Radiochemistry as my bible. This book was based on a series of lectures which Professor Hahn had given at Cornell in 1933; it set forth the "laws" for the co-precipitation of minute quantities of radioactive materials when insoluble substances were precipitated from aqueous solutions. I recall reading and rereading every word in these laws of co-precipitation many times, attempting to derive every possible bit of guidance for our work, and perhaps in my zealousness reading into them more than the master himself had intended. I doubt that I have read sections in any other book more carefully or more frequently than those in Hahn's Applied Radiochemistry. In fact, I read the entire volume repeatedly and I recall that my chief disappointment with it was its length. It was too short.

In 1924, Hahn was elected to full membership of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, by a vote of thirty white balls to two black.[50] While still remaining the head of his own department, he became Deputy Director of the KWIC in 1924, and succeeded Alfred Stock as the director in 1928.[51] Meitner became the director of the Physical Radioactivity Division, while Hahn headed the Chemical Radioactivity Division.[52]

In the early 1920s, Hahn created a new line of research. Using the "emanation method", which he had recently developed, and the "emanation ability", he founded what became known as "applied radiochemistry" for the researching of general chemical and physical-chemical questions. In 1936 Cornell University Press published a book in English (and later in Russian) titled Applied Radiochemistry, which contained the lectures given by Hahn when he was a visiting professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, in 1933. This publication had a major influence on almost all nuclear chemists and physicists in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union during the 1930s and 1940s.[49] Hahn is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry, which emerged from applied radiochemistry.[53][54][55]

Nazi Germany

[edit]Impact of Nazism

[edit]Fritz Strassmann had come to the KWIC to study under Hahn to improve his employment prospects. After the Nazi Party (NSDAP) came to power in Germany in 1933, Strassmann declined a lucrative offer of employment because it required political training and Nazi Party membership. Later, rather than become a member of a Nazi-controlled organisation, Strassmann resigned from the Society of German Chemists when it became part of the Nazi German Labour Front. As a result, he could neither work in the chemical industry nor receive his habilitation, the prerequisite for an academic position. Meitner persuaded Hahn to hire Strassmann as an assistant. Soon he would be credited as a third collaborator on the papers they produced, and would sometimes even be listed first.[56][57]

Hahn spent February to June 1933 in the United States and Canada as a visiting professor at Cornell University.[58] He gave an interview to the Toronto Star Weekly in which he painted a flattering portrait of Adolf Hitler:

I am not a Nazi. But Hitler is the hope, the powerful hope, of German youth... At least 20 million people revere him. He began as a nobody, and you see what he has become in ten years.... In any case for the youth, for the nation of the future, Hitler is a hero, a Führer, a saint... In his daily life he is almost a saint. No alcohol, not even tobacco, no meat, no women. In a word: Hitler is an unequivocal Christ.[59]

The April 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service banned Jews and communists from academia. Meitner was exempt from its impact because she was an Austrian rather than a German citizen.[60] Haber was likewise exempt as a veteran of World War I, but chose to resign his directorship of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in protest on 30 April 1933. The directors of the other Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes, even the Jewish ones, complied with the new law,[61] which applied to the KWS as a whole and those Kaiser Wilhelm institutes with more than 50% state support, which exempted the KWI for Chemistry.[62] Hahn therefore did not have to fire any of his own full-time staff, but as the interim director of Haber's institute, he dismissed a quarter of its staff, including three department heads. Gerhart Jander was appointed the new director of Haber's old institute, and reoriented it towards chemical warfare research.[63]

Like most KWS institute directors, Haber had accrued a large discretionary fund. It was his wish that it be distributed to the dismissed staff to facilitate their emigration. Hahn brokered a deal whereby 10 per cent of the funds would be allocated to Haber's people and the rest to KWS, but the Rockefeller Foundation insisted that the funds be used for their original scientific research or else be returned. In August 1933 the administrators of the KWS were alerted that several boxes of Rockefeller Foundation-funded equipment were about to be shipped to Herbert Freundlich, one of the department heads that Hahn had dismissed, who was now working in England. Ernst Telschow, a Nazi Party member, was in charge while Planck, the president of the KWS since 1930, was on vacation, and he ordered the shipment halted. Hahn complied, but he disagreed with the decision on the grounds that funds from abroad should not be diverted to military research, which the KWS was increasingly undertaking. When Planck returned from vacation, he ordered Hahn to expedite the shipment.[64][65]

Haber died on 29 January 1934. A memorial service was held on the first anniversary of his death. University professors were forbidden to attend, so they sent their wives in their place. Hahn, Planck and Joseph Koeth attended, and gave speeches.[63][66] The ageing Planck did not seek re-election, and was succeeded in 1937 as president by Carl Bosch, a winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the chairman of the board of IG Farben, a company which had bankrolled the Nazi Party since 1932. Telschow became Secretary of the KWS. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the Nazis, but was also loyal to Hahn, being one of his former students, and Hahn welcomed his appointment.[67][63] Hahn's chief assistant, Otto Erbacher, became the KWI for Chemistry's party steward (Vertrauensmann).[68]

Rubidium–strontium dating

[edit]While Hahn was in North America in 1905–1906, his attention had been drawn to a mica-like mineral from Manitoba that contained rubidium. He had studied the radioactive decay of rubidium-87, and had estimated its half-life at 2 x 1011 years. It occurred to him that by comparing the quantity of strontium in the mineral (which had once been rubidium) with that of the remaining rubidium, he could measure the age of the mineral, assuming that his original calculation of the half-life was reasonably accurate. This would be a superior dating method to studying the decay of uranium, because some of the uranium turns into helium, which then escapes, resulting in rocks appearing to be younger than they really were. Jacob Papish helped Hahn obtain several kilograms of the mineral.[69]

In 1937, Strassmann and Ernst Walling extracted 253.4 milligrams of strontium carbonate from 1,012 grams of the mineral, all of which was the strontium-87 isotope, indicating that it had all been produced from radioactive decay of rubidium-87. The age of the mineral had been estimated at 1,975 million years from uranium minerals in the same deposit, which implied that the half-life of rubidium-87 was 2.3 x 1011 years: quite close to Hahn's original calculation.[70][71] Rubidium–strontium dating became a widely used technique for dating rocks in the 1950s, when mass spectrometry became common.[72]

Discovery of nuclear fission

[edit]

After James Chadwick discovered the neutron in 1932,[75] Irène Curie and Frédéric Joliot irradiated aluminium foil with alpha particles. They found that this results in a short-lived radioactive isotope of phosphorus. They noted that positron emission continued after the neutron emissions ceased. Not only had they discovered a new form of radioactive decay, they had transmuted an element into a hitherto unknown radioactive isotope of another, thereby inducing radioactivity where there had been none before. Radiochemistry was now no longer confined to certain heavy elements, but extended to the entire periodic table.[76][77] Chadwick noted that being electrically neutral, neutrons could penetrate the atomic nucleus more easily than protons or alpha particles.[78] Enrico Fermi and his colleagues in Rome picked up on this idea,[79] and began irradiating elements with neutrons.[80]

The radioactive displacement law of Fajans and Soddy said that beta decay causes isotopes to move one element up on the periodic table, and alpha decay causes them to move two down. When Fermi's group bombarded uranium atoms with neutrons, they found a complex mix of half-lives. Fermi therefore concluded that the new elements with atomic numbers greater than 92 (known as transuranium elements) had been created.[80] Meitner and Hahn had not collaborated for many years, but Meitner was eager to investigate Fermi's results. Hahn, initially, was not, but he changed his mind when Aristid von Grosse suggested that what Fermi had found was an isotope of protactinium.[81] They set out to determine whether or not the 13-minute isotope was indeed an isotope of protactinium.[82]

Between 1934 and 1938, Hahn, Meitner and Strassmann found a great number of radioactive transmutation products, all of which they regarded as transuranic.[83] At that time, the existence of actinides was not yet established, and uranium was wrongly believed to be a group 6 element similar to tungsten. It followed that the first transuranic elements would be similar to group 7 to 10 elements, i.e. rhenium and platinoids. They established the presence of multiple isotopes of at least four such elements, and (mistakenly) identified them as elements with atomic numbers 93 through 96. They were the first scientists to measure the 23-minute half-life of uranium-239 and to establish chemically that it was an isotope of uranium, but were unable to continue this work to its logical conclusion and identify the real element 93.[84] They identified ten different half-lives, with varying degrees of certainty. To account for them, Meitner had to hypothesise a new class of reaction and the alpha decay of uranium, neither of which had ever been reported before, and for which physical evidence was lacking. Hahn and Strassmann refined their chemical procedures, while Meitner devised new experiments to shine more light on the reaction processes.[84]

In May 1937, they issued parallel reports, one in the Zeitschrift für Physik with Meitner as the principal author, and one in the Chemische Berichte with Hahn as the principal author.[84][85][86] Hahn concluded his by stating emphatically: Vor allem steht ihre chemische Verschiedenheit von allen bisher bekannten Elementen außerhalb jeder Diskussion ("Above all, their chemical distinction from all previously known elements needs no further discussion").[86] Meitner, however, was increasingly uncertain. She considered the possibility that the reactions were from different isotopes of uranium; three were known: uranium-238, uranium-235 and uranium-234. However, when she calculated the neutron cross section, it was too large to be anything other than the most abundant isotope, uranium-238. She concluded that it must be another case of the nuclear isomerism that Hahn had discovered in protactinium. She therefore ended her report on a very different note to Hahn,[87] reporting that: Also müssen die Prozesse Einfangprozesse des Uran 238 sein, was zu drei isomeren Kernen Uran 239 führt. Dieses Ergebnis ist mit den bisherigen Kernvorstellungen sehr schwer in Übereinstimmung zu bringen ("The processes must be neutron capture by uranium-238, which leads to three isomeric nuclei of uranium-239. This result is very difficult to reconcile with current concepts of the nucleus.")[85]

With the Anschluss, Germany's annexation of Austria on 12 March 1938, Meitner lost her Austrian citizenship,[88] and fled to Sweden. She carried only a little money, but before she left, Hahn gave her a diamond ring he had inherited from his mother.[89] Meitner continued to correspond with Hahn by mail. In late 1938 Hahn and Strassmann found evidence of isotopes of an alkaline earth metal in their sample. Finding a group 2 metal was problematic, because it did not logically fit with the other elements found thus far. Hahn initially suspected it to be radium, produced by splitting off two alpha-particles from the uranium nucleus, but chipping off two alpha particles via this process was unlikely. The idea of turning uranium into barium (by removing around 100 nucleons) was seen as preposterous.[90]

During a visit to Copenhagen on 10 November, Hahn discussed these results with Niels Bohr, Meitner, and Otto Robert Frisch.[90] Further refinements of the technique, leading to the decisive experiment on 16–17 December 1938, produced puzzling results: the three isotopes consistently behaved not as radium, but as barium. Hahn, who did not inform the physicists in his Institute, described the results exclusively in a letter to Meitner on 19 December:

We are more and more coming to the awful conclusion that our Ra isotopes behave not like Ra, but like Ba... Perhaps you can come up with some fantastic explanation. We ourselves realize that it can't actually burst apart into Ba. Now we want to test whether the Ac-isotopes derived from the "Ra" behave not like Ac but like La.[91]

In her reply, Meitner concurred. "At the moment, the interpretation of such a thoroughgoing breakup seems very difficult to me, but in nuclear physics we have experienced so many surprises, that one cannot unconditionally say: 'it is impossible'." On 22 December 1938, Hahn sent a manuscript to Naturwissenschaften reporting their radiochemical results, which were published on 6 January 1939.[92] On 27 December, Hahn telephoned the editor of the Naturwissenschaften and requested an addition to the article, speculating that some platinum group elements previously observed in irradiated uranium, which were originally interpreted as transuranium elements, could in fact be technetium (then called "masurium"), mistakenly believing that the atomic masses had to add up rather than the atomic numbers. By January 1939, he was sufficiently convinced of the formation of light elements that he published a new revision of the article, retracting former claims of observing transuranic elements and neighbours of uranium.[93]

As a chemist, Hahn was reluctant to propose a revolutionary discovery in physics, but Meitner and Frisch worked out a theoretical interpretation of nuclear fission, a term appropriated by Frisch from biology. In January and February they published two articles discussing and experimentally confirming their theory.[94][95][96] In their second publication on nuclear fission, Hahn and Strassmann used the term Uranspaltung (uranium fission) for the first time, and predicted the existence and liberation of additional neutrons during the fission process, opening up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction.[97] This was shown to be the case by Frédéric Joliot and his team in March 1939.[98] Edwin McMillan and Philip Abelson used the cyclotron at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory to bombard uranium with neutrons, and were able to identify an isotope with a 23-minute half-life that was the daughter of uranium-239, and therefore the real element 93, which they named neptunium.[99] "There goes a Nobel Prize", Hahn remarked.[100]

At the KWIC, Kurt Starke independently produced element 93, using only the weak neutron sources available there. Hahn and Strassmann then began researching its chemical properties.[101] They knew that it should decay into the real element 94, which according to the latest version of the liquid drop model of the nucleus propounded by Bohr and John Archibald Wheeler, would be even more fissile than uranium-235, but were unable to detect its radioactive decay. They concluded that it must have an extremely long half-life, perhaps millions of years.[99] Part of the problem was that they still believed that element 94 was a platinoid, which confounded their attempts at chemical separation.[101]

World War II

[edit]On 24 April 1939, Paul Harteck and his assistant, Wilhelm Groth, had written to the Armed Forces High Command (OKW), alerting it to the possibility of the development of an atomic bomb. In response, the Army Weapons Branch (HWA) had established a physics section under the nuclear physicist Kurt Diebner. After World War II broke out on 1 September 1939, the HWA moved to control the German nuclear weapons program. From then on, Hahn participated in a ceaseless series of meetings related to the project. After the Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, Peter Debye, left for the United States in 1940 and never returned, Diebner was installed as its director.[102] Hahn reported to the HWA on the progress of his research. Together with his assistants, Hans-Joachim Born, Siegfried Flügge, Hans Götte, Walter Seelmann-Eggebert and Strassmann, he catalogued about one hundred fission product isotopes. They also investigated means of isotope separation; the chemistry of element 93; and methods for purifying uranium oxides and salts.[103]

On the night of 15 February 1944, the KWIC building was struck by a bomb.[103] Hahn's office was destroyed, along with his correspondence with Rutherford and other researchers, and many of his personal possessions.[104][105] The office was the intended target of the raid, which had been ordered by Brigadier General Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, in the hope of disrupting the German uranium project.[106] Albert Speer, the Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production, arranged for the institute to move to Tailfingen (today part of Albstadt) in southern Germany. All work in Berlin ceased by July. Hahn and his family moved to the house of a textile manufacturer there.[104][105]

Life became precarious for those married to Jewish women. One was Philipp Hoernes, a chemist working for Auergesellschaft, the firm that mined the uranium ore used by the project. After the firm let him go in 1944, Hoernes faced being conscripted for forced labour. At the age of 60, it was doubtful that he would survive. Hahn and Nikolaus Riehl arranged for Hoernes to work at the KWIC, claiming that his work was essential to the uranium project and that uranium was highly toxic, making it hard to find people to work with it. Hahn was aware that uranium ore was fairly safe in the laboratory, although not so much for the 2,000 female slave labourers from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp who mined it in Oranienburg. Another physicist with a Jewish wife was Heinrich Rausch von Traubenberg. Hahn certified that his work was important to the war effort, and that his wife Maria, who had a doctorate in physics, was required as his assistant. After he died on 19 September 1944, Maria faced being sent to a concentration camp. Hahn mounted a lobbying campaign to get her released, but to no avail, and she was sent to the Theresienstadt Ghetto in January 1945. She survived the war, and was reunited with her daughters in England.[107][108]

Post-war

[edit]Incarceration in Farm Hall

[edit]On 25 April 1945, an armoured task force from the British−American Alsos Mission arrived in Tailfingen, and surrounded the KWIC. Hahn was informed that he was under arrest. When asked about reports related to his secret work on uranium, Hahn replied "I have them all here" and handed over 150 reports. He was taken to Hechingen, where he joined Erich Bagge, Horst Korsching, Max von Laue, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Karl Wirtz. They were then taken to a dilapidated château in Versailles, where they heard about the signing of the German Instrument of Surrender at Reims on 7 May. Over the following days they were joined by Kurt Diebner, Walther Gerlach, Paul Harteck and Werner Heisenberg.[109][110][111] All were physicists except Hahn and Harteck, who were chemists, and all had worked on the German nuclear weapons program except von Laue, although he was well aware of it.[112]

They were moved to the Château de Facqueval in Modave, Belgium, where Hahn used the time to work on his memoirs and then, on 3 July, were flown to England. They arrived at Farm Hall, Godmanchester, near Cambridge, on 3 July. While they were there, all their conversations, indoors and out, were covertly recorded with hidden microphones. They were given British newspapers, which Hahn was able to read. He was greatly disturbed by their reports of the Potsdam Conference, where German territory was ceded to Poland and the USSR. In August 1945, the German scientists were informed of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Up to this point the scientists, except Harteck, were completely certain that their project was further advanced than any in other countries, and the Alsos Mission's chief scientist, Samuel Goudsmit, did nothing to correct this impression. Now the reason for their incarceration in Farm Hall suddenly became apparent.[112][113][114][115]

As they recovered from the shock of the announcement, they began to rationalise what had happened. Hahn noted that he was glad that they had not succeeded, and von Weizsäcker suggested that they should claim that they had not wanted to. They drafted a memorandum on the project, noting that fission was discovered by Hahn and Strassmann. The revelation that Nagasaki had been destroyed by a plutonium bomb came as another shock, as it meant that the Allies had not only been able to conduct uranium enrichment, but had mastered nuclear reactor technology as well. The memorandum became the first draft of a postwar apologia. The idea that Germany had lost the war because its scientists were morally superior was as outrageous as it was unbelievable, but struck a chord in postwar German academe.[116] It infuriated Goudsmit, whose parents had been murdered in Auschwitz.[117] On 3 January 1946, six months after they had arrived at Farm Hall, the group was allowed to return to Germany.[118] Hahn, Heisenberg, von Laue and von Weizsäcker were brought to Göttingen, which was controlled by the British occupation authorities.[119]

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1944

[edit]On 16 November 1945 the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that Hahn had been awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his discovery of the fission of heavy atomic nuclei."[120][121] Hahn was still at Farm Hall when the announcement was made; thus, his whereabouts were a secret, and it was impossible for the Nobel committee to send him a congratulatory telegram. Instead, he learned about his award on 18 November through the Daily Telegraph.[122] His fellow interned scientists celebrated his award by giving speeches, making jokes, and composing songs.[123]

Hahn had been nominated for the chemistry and the physics Nobel prizes many times even before the discovery of nuclear fission. Several more followed for the discovery of fission.[40] The Nobel prize nominations were vetted by committees of five, one for each award. Although Hahn and Meitner received nominations for physics, radioactivity and radioactive elements had traditionally been seen as the domain of chemistry, and so the Nobel Committee for Chemistry evaluated the nominations. The committee received reports from Theodor Svedberg and Arne Westgren. These chemists were impressed by Hahn's work, but felt that of Meitner and Frisch was not extraordinary, and did not understand why the physics community regarded their work as seminal. As for Strassmann, although his name was on the papers, there was a long-standing policy of conferring awards on the most senior scientist in a collaboration. The committee therefore recommended that Hahn alone be given the chemistry prize.[124]

Under Nazi rule, Germans had been forbidden to accept Nobel prizes after the Nobel Peace Prize had been awarded to Carl von Ossietzky in 1936.[125] The Nobel Committee for Chemistry's recommendation was therefore rejected by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1944, which also decided to defer the award for one year. When the Academy reconsidered the award in September 1945, the war was over and thus the German boycott had ended. Also, the chemistry committee had now become more cautious, as it was apparent that much research had taken place in the United States in secret, and suggested deferring for another year, but the Academy was swayed by Göran Liljestrand, who argued that it was important for the Academy to assert its independence from the Allies of World War II, and award the prize to a German, as it had done after World War I when it had awarded it to Fritz Haber. Hahn therefore became the sole recipient of the 1944 Nobel Prize for Chemistry.[124]

The invitation to attend the Nobel festivities was transmitted via the British Embassy in Stockholm.[126] On 4 December, Hahn was persuaded by two of his Alsos captors, American Lieutenant Colonel Horace K. Calvert and British Lieutenant Commander Eric Welsh, to write a letter to the Nobel committee accepting the prize but stating that he would not be able to attend the award ceremony on 10 December since his captors would not allow him to leave Farm Hall. When Hahn protested, Welsh reminded him that Germany had lost the war.[127] Under the Nobel Foundation statutes, Hahn had six months to deliver the Nobel Prize lecture, and until 1 October 1946 to cash the 150,000 Swedish krona cheque.[128][129]

Hahn was repatriated from Farm Hall on 3 January 1946, but it soon became apparent that difficulties obtaining permission to travel from the British government meant that he would be unable to travel to Sweden before December 1946. Accordingly, the Academy of Sciences and the Nobel Foundation obtained an extension from the Swedish government.[129] Hahn attended the year after he was awarded the prize. On 10 December 1946, the anniversary of the death of Alfred Nobel, King Gustav V of Sweden presented him with his Nobel Prize medal and diploma.[121][129][130] Hahn gave 10,000 krona of his prize to Strassmann, who refused to use it.[130][131]

Founder and President of the Max Planck Society

[edit]

The suicide of Albert Vögler on 14 April 1945 left the KWS without a president.[51] The British chemist Bertie Blount was placed in charge of its affairs while the Allies decided what to do with it, and he decided to install Max Planck as an interim president. Now aged 87, Planck was in the small town of Rogätz, in an area that the Americans were preparing to hand over to the Soviet Union. The Dutch astronomer Gerard Kuiper from the Alsos Mission fetched Planck in a Jeep and brought him to Göttingen on 16 May.[132][133] Planck wrote to Hahn, who was still in captivity in England, on 25 July, and informed Hahn that the directors of the KWS had voted to make him the next president, and asked if he would accept the position.[51] Hahn did not receive the letter until September, and did not think he was a good choice, as he regarded himself as a poor negotiator, but his colleagues persuaded him to accept. After his return to Germany, he assumed the office on 1 April 1946.[134][135]

Allied Control Council Law No. 25 on the control of scientific research dated 29 April 1946 restricted German scientists to conducting basic research only,[51] and on 11 July the Allied Control Council dissolved the KWS on the insistence of the Americans,[136] who considered that it had been too close to the national socialist regime, and was a threat to world peace.[137] However, the British, who had voted against the dissolution, were more sympathetic, and offered to let the Kaiser Wilhelm Society continue in the British Zone, on one condition: that the name be changed. Hahn and Heisenberg were distraught at this prospect. To them it was an international brand that represented political independence and scientific research of the highest order. Hahn noted that it had been suggested that the name be changed during the Weimar Republic, but the Social Democratic Party of Germany had been persuaded not to.[138] To Hahn, the name represented the good old days of the German Empire, however authoritarian and undemocratic it was, before the hated Weimar Republic.[139] Heisenberg asked Niels Bohr for support, but Bohr recommended that the name be changed.[138] Lise Meitner wrote to Hahn, explaining that:

Outside of Germany it is considered so obvious that the tradition from the period of Kaiser Wilhelm has been disastrous and that changing the name of the KWS is desirable, that no one understands the resistance against it. For the idea, that the Germans are the chosen people and have the right to use any and all means to subordinate the "inferior" people, has been expressed over and over again by historians, philosophers, and politicians and finally the Nazis tried to translate it into fact... The best people among the English and Americans wish that the best Germans would understand that there should be a definitive break with this tradition, which has brought the entire world and Germany itself the greatest misfortune. And as a small sign of German understanding the name of the KWS should be changed. What's in a name, if it is a matter of the existence of Germany and thereby Europe?[140]

In September 1946, a new Max Planck Society was established at Bad Driburg in the British Zone.[137] On 26 February 1948, after the US and British zones were fused into Bizonia, it was dissolved to make way for the Max Planck Society, with Hahn as the founding president. It took over the 29 institutes of the former Kaiser Wilhelm Society that were located in the British and American zones. When the Federal Republic of Germany (or West-Germany) was formed in 1949, the five institutes located in the French zone joined them.[141] The KWIC, now under Strassmann, built and renovated new accommodation in Mainz, but work proceeded slowly, and it did not relocate from Tailfingen until 1949.[142] Hahn's insistence on retaining Telschow as the general secretary nearly caused a rebellion against his presidency.[143] In his efforts to rebuild German science, Hahn was generous in issuing persilschein (whitewash certificates), writing one for Gottfried von Droste, who had joined the Sturmabteilung (SA) in 1933 and the NSDAP in 1937, and wore his SA uniform at the KWIC,[144] and for Heinrich Hörlein and Fritz ter Meer from IG Farben.[145] Hahn served as president of the Max Planck Society until 1960, and succeeded in regaining the renown that had once been enjoyed by the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. New institutes were founded and old ones expanded, the budget rose from 12 million Deutsche Marks in 1949 (equivalent to €32 million in 2021) to 47 million in 1960 (equivalent to €115 million in 2021), and the workforce grew from 1,400 to nearly 3,000.[51]

Spokesman for social responsibility

[edit]After the Second World War, Hahn came out strongly against the use of nuclear energy for military purposes. He saw the application of his scientific discoveries to such ends as a misuse, or even a crime. The historian Lawrence Badash wrote: "His wartime recognition of the perversion of science for the construction of weapons, and his postwar activity in planning the direction of his country's scientific endeavours now inclined him increasingly toward being a spokesman for social responsibility."[146]

In early 1954, he wrote the article "Cobalt 60 – Danger or Blessing for Mankind?", about the misuse of atomic energy, which was widely reprinted and transmitted in the radio in Germany, Norway, Austria, and Denmark, and in an English version worldwide via the BBC. The international reaction was encouraging.[147] The following year he initiated and organised the Mainau Declaration of 1955, in which he and other international Nobel Prize-winners called attention to the dangers of atomic weapons and urgently warned the nations of the world against the use of "force as a final resort", and which was issued a week after the similar Russell-Einstein Manifesto. In 1956, Hahn repeated his appeal with the signature of 52 of his Nobel colleagues from all parts of the world.[148]

Hahn was also instrumental in and one of the authors of the Göttingen Manifesto of 13 April 1957, in which, together with 17 leading German atomic scientists, he protested against a proposed nuclear arming of the West German armed forces (Bundeswehr).[149] This resulted in Hahn receiving an invitation to meet the Chancellor of Germany, Konrad Adenauer and other senior officials, including the Defense Minister, Franz Josef Strauss, and Generals Hans Speidel and Adolf Heusinger (who had both been generals in the Nazi era). The two generals argued that the Bundeswehr needed nuclear weapons, and Adenauer accepted their advice. A communiqué was drafted that said that the Federal Republic did not manufacture nuclear weapons, and would not ask its scientists to do so.[150] Instead, the German forces were equipped with US nuclear weapons.[151]

On 13 November 1957, in the Konzerthaus (Concert Hall) in Vienna, Hahn warned of the "dangers of A- and H-bomb-experiments", and declared that "today war is no means of politics anymore – it will only destroy all countries in the world". His highly acclaimed speech was transmitted internationally by the Austrian radio, Österreichischer Rundfunk (ÖR). On 28 December 1957, Hahn repeated his appeal in an English translation for the Bulgarian Radio in Sofia, which was broadcast in all Warsaw pact states.[152][153]

In 1959 Hahn co-founded in Berlin the Federation of German Scientists (VDW), a non-governmental organisation, which has been committed to the ideal of responsible science. The members of the Federation feel committed to taking into consideration the possible military, political, and economic implications and possibilities of atomic misuse when carrying out their scientific research and teaching. With the results of its interdisciplinary work the VDW not only addresses the general public, but also the decision-makers at all levels of politics and society.[154] Right up to his death, Otto Hahn never tired of warning of the dangers of the nuclear arms race between the great powers and of the radioactive contamination of the planet.[155]

Lawrence Badash wrote:

The important thing is not that scientists may disagree on where their responsibility to society lies, but that they are conscious that a responsibility exists, are vocal about it, and when they speak out they expect to affect policy. Otto Hahn, it would seem, was even more than just an example of this twentieth-century conceptual evolution; he was a leader in the process.[156]

He was one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution.[157][158] As a result, for the first time in human history, a World Constituent Assembly convened to draft and adopt a Constitution for the Federation of Earth.[159]

Private life

[edit]

In June 1911, while attending a conference in Stettin, Hahn met Edith Junghans (1887–1968), a student at the Royal School of Art in Berlin. They saw each other again in Berlin, and became engaged in November 1912. On 22 March 1913 the couple were married in Stettin, where Edith's father, Paul Ferdinand Junghans, was a high-ranking law officer and President of the City Parliament until his death in 1915. After a honeymoon at Punta San Vigilio on Lake Garda in Italy, they visited Vienna, and then Budapest, where they stayed with George de Hevesy.[160]

They had one child, Hanno Hahn, who was born on 9 April 1922.[161] Hanno enlisted in the army in 1942, and served on the Eastern Front in World War II as a panzer commander. He lost an arm in combat. After the war he became an art historian and architectural researcher (at the Hertziana in Rome), known for his discoveries in the early Cistercian architecture of the 12th century. In August 1960, while on a study trip in France, Hanno died in a car accident, together with his wife and assistant Ilse Hahn née Pletz. They left a fourteen-year-old son, Dietrich Hahn.[161]

In 1990, the Hanno and Ilse Hahn Prize for outstanding contributions to Italian art history was established in memory of Hanno and Ilse Hahn to support young and talented art historians. It is awarded biennially by the Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History in Rome.[162]

Death and legacy

[edit]Death

[edit]

Hahn was shot in the back in October 1951 by a disgruntled inventor who wished to highlight the neglect of his ideas by mainstream scientists. Hahn was injured in a motor vehicle accident in 1952, and had a minor heart attack the following year. In 1962, he published a book, Vom Radiothor zur Uranspaltung (lit. 'From Radiothorium to Uranium Fission'). It was released in English in 1966 with the title Otto Hahn: A Scientific Autobiography, with an introduction by Glenn Seaborg. The success of this book may have prompted him to write another, fuller autobiography, Otto Hahn. Mein Leben, but before it could be published, he fractured one of the vertebrae in his neck while getting out of a car. He gradually became weaker and died in Göttingen on 28 July 1968. His wife Edith survived him by only a fortnight.[163] He was buried in the Stadtfriedhof in Göttingen.[164][165] The day after his death, the Max Planck Society published the following obituary notice:

On 28 July, in his 90th year, our Honorary President Otto Hahn passed away. His name will be recorded in the history of humanity as the founder of the atomic age. In him Germany and the world have lost a scholar who was distinguished in equal measure by his integrity and personal humility. The Max Planck Society mourns its founder, who continued the tasks and traditions of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society after the war, and mourns also a good and much loved human being, who will live in the memories of all who had the chance to meet him. His work will continue. We remember him with deep gratitude and admiration.[166]

Fritz Strassmann wrote:

The number of those who had been able to be near Otto Hahn is small. His behaviour was completely natural for him, but for the next generations he will serve as a model, regardless of whether one admires in the attitude of Otto Hahn his humane and scientific sense of responsibility or his personal courage.[167]

Otto Robert Frisch recalled:

Hahn remained modest and informal all his life. His disarming frankness, unfailing kindness, good common sense, and impish humour will be remembered by his many friends all over the world.[168]

The Royal Society in London wrote in an obituary:

It was remarkable, how, after the war, this rather unassuming scientist who had spent a lifetime in the laboratory, became an effective administrator and an important public figure in Germany. Hahn, famous as the discoverer of nuclear fission, was respected and trusted for his human qualities, simplicity of manner, transparent honesty, common sense and loyalty.[169]

Legacy

[edit]Hahn is considered the father of radiochemistry and nuclear chemistry.[53] He is chiefly remembered for the discovery of nuclear fission, the basis of nuclear power and nuclear weapons.[170] Glenn Seaborg wrote that "it has been given to very few men to make contributions to science and to humanity of the magnitude of those made by Otto Hahn".[53] His award of the 1944 Nobel Prize for Chemistry was in recognition for this discovery. However later commentators have argued that Lise Meitner's exclusion reflected sexism and antisemitism within the Nobel Committee.[171] Conflict between chemists and physicists and the theorists and experimentalists also played a role.[124][vague] Hahn's efforts to rehabilitate the image of Germany after the war have also been viewed as problematic. Hahn has been described as politically passive during the Nazi era, suggesting that while he was not a party member, he tolerated colleagues who were and thus shared moral complicity.[171][144][145] In a letter to James Franck dated 22 February 1946, Meitner wrote:

Hahn is without doubt a decent man with many good traits. He only lacks thoughtfulness and perhaps also a certain strength of character, things that in normal times are minor flaws, but in the complicated times of today have deeper implications.[171]

Honours and awards

[edit]During his lifetime Hahn was awarded orders, medals, scientific prizes, and fellowships of Academies, Societies, and Institutions from all over the world. At the end of 1999, the German news magazine Focus published an inquiry of 500 leading natural scientists, engineers, and physicians about the most important scientists of the 20th century. In this poll Hahn was elected third (with 81 points), after the theoretical physicists Albert Einstein and Max Planck, and thus the most significant chemist of his time.[172]

As well as the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1944), Hahn was awarded:

- the Emil Fischer Medal of the Society of German Chemists (1922),[173]

- the Cannizaro Prize of the Royal Academy of Science in Rome (1938),[173]

- the Copernicus Prize of the University of Konigsberg (1941),[173]

- the Gothenius Medal of the Akademie der Naturforscher (1943),[173]

- the Max Planck Medal of the German Physical Society, with Lise Meitner (1949),[173]

- the Goethe Medal of the city of Frankfurt-on-the-Main (1949),[173]

- the Golden Paracelsus Medal of the Swiss Chemical Society (1953),[173]

- the Faraday Lectureship Prize with Medal from the Royal Society of Chemistry (1956),[173]

- the Grotius Medal of the Hugo Grotius Foundation (1956),[173]

- the Wilhelm Exner Medal of the Austrian Industry Association (1958),[174]

- the Helmholtz Medal of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (1959),

- and the Harnack medal in Gold from the Max Planck Society (1959).[175][176]

Hahn became the honorary president of the Max Planck Society in 1962.[177]

- He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (1957).[178]

- His honorary memberships of foreign academies and scientific societies included:

- the Romanian Physical Society in Bucharest,[179]

- the Royal Spanish Society for Chemistry and Physics and the Spanish National Research Council,[179]

- and the Academies in Allahabad, Bangalore, Berlin, Boston, Bucharest, Copenhagen, Göttingen, Halle, Helsinki, Lisbon, Madrid, Mainz, Munich, Rome, Stockholm, the Vatican, and Vienna.[179]

He was an honorary fellow of University College London,[179]

- and an honorary citizen of the cities of Frankfurt am Main and Göttingen in 1959, and of Berlin (1968).[173]

- Hahn was made an Officer of the Ordre National de la Légion d'Honneur of France (1959),[173]

- and was awarded the Grand Cross First Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1959).[173]

- In 1966, US President Lyndon B. Johnson and the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) awarded Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann the Enrico Fermi Award. The diploma for Hahn bore the words: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies culminating in the discovery of fission."[180]

- He received honorary doctorates from

- the University of Gottingen,[173]

- the Technische Universität Darmstadt,[173]

- the Goethe University Frankfurt in 1949,[173]

- and the University of Cambridge in 1957.[173]

Objects named after Hahn include:

- NS Otto Hahn, the only European nuclear-powered civilian ship (1964);[181][182]

- a crater on the Moon (shared with his namesake Friedrich von Hahn);[183]

- and the asteroid 19126 Ottohahn;[184]

- the Otto Hahn Prize of both the German Chemical and Physical Societies and the city of Frankfurt/Main;[185]

- the Otto Hahn Medal – An Incentive for Young Scientists – and the Otto Hahn Award of the Max Planck Society;[186][187]

- and the Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold of the United Nations Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin (1988).[188]

Proposals were made at various times, first in 1971 by American chemists, that the newly synthesised element 105 should be named hahnium in Hahn's honour, but in 1997 the IUPAC named it dubnium, after the Russian research centre in Dubna. In 1992 element 108 was discovered by a German research team, and they proposed the name hassium (after Hesse). In spite of the long-standing convention to give the discoverer the right to suggest a name, a 1994 IUPAC committee recommended that it be named hahnium.[189] After protests from the German discoverers, the name hassium (Hs) was adopted internationally in 1997.[190]

See also

[edit]Publications in English

[edit]- Hahn, Otto (1936). Applied Radiochemistry. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Hahn, Otto (1950). New Atoms: Progress and Some Memories. New York-Amsterdam-London-Brussels: Elsevier Inc.

- Hahn, Otto (1966). Otto Hahn: A Scientific Autobiography. Translated by Ley, Willy. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Hahn, Otto (1970). My Life. Translated by Kaiser, Ernst; Wilkins, Eithne. New York: Herder and Herder.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 2–6.

- ^ a b Hahn 1966, pp. 7–11.

- ^ Spence 1970, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Hughes 2009, p. 135.

- ^ Hoffmann 2001, p. 35.

- ^ "A New Element". The Daily Telegraph. London. 18 March 1905.

- ^ Hahn, Otto (24 May 1905). "A New Radio-active Element, Which Evolves Thorium Emanation. Preliminary Communication". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 76 (508): 115–117. Bibcode:1905RSPSA..76..115H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1905.0009. ISSN 0080-4630.

- ^ Spence 1970, pp. 303–313 for a full list

- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 15–18.

- ^ Spence 1970, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Hahn 1988, p. 59.

- ^ Hahn 1966, p. 66.

- ^ a b Hahn 1966, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Hahn 1966, p. 52.

- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 40–50.

- ^ "Nobel Prize for Chemistry for 1944: Prof. Otto Hahn". Nature. 156 (3970): 657. December 1945. Bibcode:1945Natur.156R.657.. doi:10.1038/156657b0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Hahn 1966, p. 68.

- ^ Stolz 1989, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Hahn 1966, p. 50.

- ^ Hahn 1966, p. 65.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Hahn 1966, pp. 58–64.

- ^ a b Gerlach & Hahn 1984, p. 39.

- ^ Sime 1996, p. 368.

- ^ "Ehrung der Physikerin Lise Meitner Aus dem Otto-Hahn-Bau wird der Hahn-Meitner-Bau" [Honouring physicist Lise Meitner as the Otto Hahn building becomes the Hahn-Meitner building] (in German). Free University of Berlin. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Sime 1996, p. 48.

- ^ Spence 1970, pp. 286–287.

- ^ a b c Van der Kloot, W. (2004). "April 1918: Five Future Nobel Prize-winners Inaugurate Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Academic-industrial-military Complex". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 58 (2): 149–160. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2004.0053. ISSN 0035-9149. S2CID 145243958.

- ^ a b Sime 1996, pp. 57–61.

- ^ Spence 1970, pp. 287–288.

- ^ a b c Sime, Ruth Lewin (August 1986). "The Discovery of Protactinium". Journal of Chemical Education. 63 (8): 653–657. Bibcode:1986JChEd..63..653S. doi:10.1021/ed063p653. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ Hahn 1988, pp. 117–132.

- ^ a b Meitner, Lise (1 June 1918). "Die Muttersubstanz des Actiniums, Ein Neues Radioaktives Element von Langer Lebensdauer" [The Parent Substance of Actinium; A New Radioactive Element with a Long Lifetime]. Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie und Angewandte Physikalische Chemie (in German). 24 (11–12): 169–173. doi:10.1002/bbpc.19180241107. ISSN 0372-8323. S2CID 94448132.

- ^ Fajans, Kasimir; Morris, Donald F. C. (1973). "Discovery and Naming of the Isotopes of Element 91". Nature. 244 (5412): 137–138. Bibcode:1973Natur.244..137F. doi:10.1038/244137a0. hdl:2027.42/62921. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4224336.

- ^ a b Scerri 2020, pp. 302–306.

- ^ a b c "Nomination Archive: Otto Hahn". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Nomination Archive: Lise Meitner". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Protactinium | Pa (Element)". PubChem. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ a b Hahn 1966, pp. 95–103.

- ^ a b Berninger 1983, pp. 213–220.

- ^ Hahn, O. (1921). "Über ein neues radioaktives Zerfallsprodukt im Uran" [On a New Radioactive Decay Product in Uranium]. Die Naturwissenschaften (in German). 9 (5): 84. Bibcode:1921NW......9...84H. doi:10.1007/BF01491321. ISSN 0028-1042. S2CID 28599831.

- ^ Hahn, Otto (1923). "Uber das Uran Z und seine Muttersubstanz" [About Uranium Z and its Parent Substance]. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie (in German). 103 (1): 461–480. doi:10.1515/zpch-1922-10325. ISSN 0942-9352. S2CID 99021215.

- ^ Hoffmann 2001, p. 93.

- ^ Feather, Bretscher & Appleton 1938, pp. 530–535.

- ^ a b Hahn 1966, pp. ix–x.

- ^ Hoffmann 2001, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d e "Otto Hahn". Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Hoffmann 2001, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Hahn 1966, p. ix.

- ^ Tietz, Tabea (8 March 2018). "Otto Hahn – the Father of Nuclear Chemistry". SciHi Blog. Archived from the original on 5 March 2025. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "Otto Hahn". Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 156–157, 169.

- ^ Walker 2006, p. 122.

- ^ Hahn 1966, p. 283.

- ^ Sime 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Sime 2006, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Sime 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Sime 2006, pp. 10–12.

- ^ "Max Planck Becomes President of the KWS". Max-Planck Gesellschaft. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Walker 2006, pp. 122–123.

- ^ "The KWS Introduces the 'Führerprinzip'". Max-Planck Gesellschaft. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Sime 1996, p. 143.

- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 85–88.

- ^ Hahn, O.; Strassman, F.; Walling, E. (19 March 1937). "Herstellung wägbaren Mengen des Strontiumisotops 87 als Umwandlungsprodukt des Rubidiums aus einem kanadischen Glimmer" [Production of Weighable Amounts of the Strontium Isotope 87 as a Conversion Product of Rubidium from Canadian Mica]. Naturwissenschaften (in German). 25 (12): 189. Bibcode:1937NW.....25..189H. doi:10.1007/BF01492269. ISSN 0028-1042.

- ^ Hahn, O.; Walling, E. (12 March 1938). "Über die Möglichkeit geologischer Alterbestimmung rubidiumhaltiger Mineralen und Gesteine" [On the Possibility of Geological Age Determination of Minerals and Rocks Containing Rubidium]. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie (in German). 236 (1): 78–82. doi:10.1002/zaac.19382360109. ISSN 0044-2313.

- ^ Bowen 1994, pp. 162–163.

- ^ "Originalgeräte zur Entdeckung der Kernspaltung, 'Hahn-Meitner-Straßmann-Tisch'" [Original equipment for the discovery of nuclear fission, 'Hahn-Meitner-Straßmann table'] (in German). Deutsches Museum. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Sime 2010, pp. 206–210.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 39, 160–167, 793.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Fergusson 2011, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b Segrè, Emilio G. (July 1989). "Discovery of Nuclear Fission". Physics Today. 42 (7): 38–43. Bibcode:1989PhT....42g..38S. doi:10.1063/1.881174. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Hahn 1966, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Hahn, O. (1958). "The Discovery of Fission". Scientific American. Vol. 198, no. 2. pp. 76–84. Bibcode:1958SciAm.198b..76H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0258-76.

- ^ a b c Sime 1996, pp. 170–172.

- ^ a b L., Meitner; O., Hahn; Strassmann, F. (May 1937). "Über die Umwandlungsreihen des Urans, die durch Neutronenbestrahlung erzeugt werden" [On the series of transformations of uranium that are generated by neutron radiation]. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 106 (3–4): 249–270. Bibcode:1937ZPhy..106..249M. doi:10.1007/BF01340321. ISSN 0939-7922. S2CID 122830315.

- ^ a b O., Hahn; L., Meitner; Strassmann, F. (9 June 1937). "Über die Trans-Urane und ihr chemisches Verhalten" [On the transuranes and their chemical behaviour]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 70 (6): 1374–1392. doi:10.1002/cber.19370700634. ISSN 0365-9496.

- ^ Sime 1996, p. 177.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 200–207.

- ^ a b Sime 1996, pp. 227–230.

- ^ Sime 1996, p. 233.

- ^ Hahn, O.; Strassmann, F. (1939). "Über den Nachweis und das Verhalten der bei der Bestrahlung des Urans mittels Neutronen entstehenden Erdalkalimetalle" [On the detection and characteristics of the alkaline earth metals formed by irradiation of uranium with neutrons]. Die Naturwissenschaften (in German). 27 (1): 11–15. Bibcode:1939NW.....27...11H. doi:10.1007/BF01488241. ISSN 0028-1042. S2CID 5920336.

- ^ Sime 1996, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Frisch 1979, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Meitner, L.; Frisch, O. R. (January 1939). "Disintegration of Uranium by Neutrons: A New Type of Nuclear Reaction". Nature. 143 (3615): 239. Bibcode:1939Natur.143..239M. doi:10.1038/143239a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4113262.