Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Merchant raider

View on Wikipedia

Merchant raiders are armed commerce raiding ships that disguise themselves as non-combatant merchant vessels.

History

[edit]Germany used several merchant raiders early in World War I (1914–1918), and again early in World War II (1939–1945). The captain of a German merchant raider, Felix von Luckner, used the sailing ship SMS Seeadler for his voyage (1916–1917). The Germans used a sailing ship at this stage of the war because coal-fired ships had limited access to fuel outside of territories held by the Central Powers due to international regulations concerning refueling of combat ships in neutral countries.[1]

Germany sent out two waves of six surface raiders each during World War II. Most of these vessels were in the 8,000–10,000 long tons (8,100–10,200 t) range. Many of these vessels had originally been refrigerator ships, used to transport fresh food from the tropics. These vessels were faster than regular merchant vessels, which was important for a warship. They were armed with six to seven 15 cm (5.9 inch) naval guns, some smaller guns, torpedoes, reconnaissance seaplanes and some were equipped for minelaying. Several captains demonstrated great creativity in disguising their vessels to masquerade as allied or as neutral merchants.

The Kormoran fought the Australian light cruiser Sydney in a mutually destructive battle in November 1941.

Italy intended to outfit four refrigerated banana boats as merchant raiders during World War II (Ramb I, Ramb II, Ramb III and Ramb IV). Only Ramb I and Ramb II served as merchant raiders and neither ship sank enemy vessels due to naval presence in the Red Sea. The New Zealand cruiser Leander sank Ramb I off the Maldives (February 1941) while it tried to make for Japan; Ramb II did reach the Far East, where the Japanese prevented her from raiding, ultimately took her over and converted her to an auxiliary transport ship. (Ramb III served as a convoy escort until torpedoed and ended up as a German minelayer, and Ramb IV was converted for the Italian Royal Navy to a hospital ship.)

These commerce raiders carried no armour because their purpose was to attack merchantmen, not to engage warships—it would also be difficult to fit armour to a civilian vessel. Eventually most were sunk or transferred to other duties.

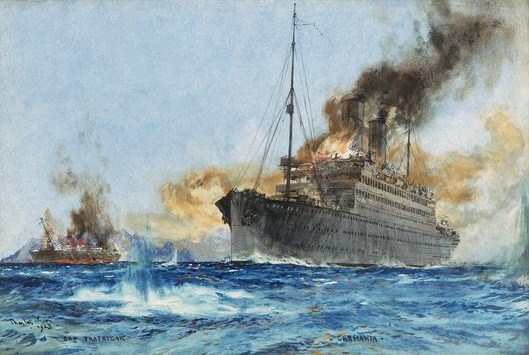

The British deployed Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMC) in World War I and in World War II. Generally adapted from passenger liners, they were larger than the German merchant raiders, were used as convoy escorts and did not disguise themselves. The British AMC Carmania sank the German SMS Cap Trafalgar which had been altered to look more like the Carmania.

During World War I, the British Royal Navy deployed Q-ships to combat German U-boats. Q-ships were warships posing as merchant ships so as to lure U-boats to attack them; their mission of destroying enemy warships differed significantly from the raider objective of disrupting enemy trade.

See also

[edit]- Armed merchantmen – Merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes

- Auxiliary cruiser Atlantis – Merchant raider used by the Nazi German Kriegsmarine during WWII

- Auxiliary cruiser Möwe – German merchant raider

- List of Japanese auxiliary cruiser commerce raiders

- Prize (law) – Vessel, cargo, or equipment captured during armed conflict on the seas

- Q-ship – Heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry

- Wolf – Armed merchant raider

References

[edit]- ^ Pardoe, Blaine L. (2005). "With the Wind at Their Backs" in Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives. National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration.

External links

[edit]- Merchant Ships Convert Into War Raiders, Paint And False Structures Provide Disguises September 1941 article details how Merchant Raiders operate in wartime

- Marauders of the Sea, German Armed Merchant Raiders During World War 1, Wolf

- Marauders of the Sea, German Armed Merchant Raiders During World War 1, Möwe

- Hilfskreuzer