Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

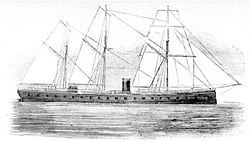

CSS Alabama

View on Wikipedia

A 1961 painting of CSS Alabama | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Alabama |

| Namesake | Alabama |

| Builder | John Laird Sons & Company |

| Laid down | 1862 |

| Launched | July 29, 1862 |

| Commissioned | August 24, 1862 |

| Motto | "Aide Toi, Et Dieu T'Aidera," (God helps those who help themselves)[1] |

| Fate | Sunk June 19, 1864 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 1050 tons |

| Length | 220 ft (67 m)[2] |

| Beam | 31 ft 8 in (9.65 m) |

| Draft | 17 ft 8 in (5.38 m) |

| Installed power | 2 × 150 HP horizontal steam engines (300 HP collectively), auxiliary sails |

| Propulsion | Single screw propeller[3] |

| Speed | 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph)[2] |

| Complement | 145 officers and men |

| Armament | 6 × 32 lb (15 kg) cannons, 1 × 110 lb (50 kg) cannon, 1 × 68 lb (31 kg) cannon |

CSS Alabama was a screw sloop-of-war built in 1862 for the Confederate States Navy. She was built in Birkenhead on the River Mersey opposite Liverpool, England, by John Laird Sons and Company.[4] Launched as Enrica, she was fitted out as a cruiser and commissioned as CSS Alabama on August 24, 1862. Under Captain Raphael Semmes, Alabama served as a successful commerce raider, attacking, capturing, and burning Union merchant and naval ships in the North Atlantic, as well as intercepting American grain ships bound for Europe. The Alabama continued through the West Indies and further into the East Indies, destroying over seven ships before returning to Europe. On June 11, 1864, the Alabama arrived at Cherbourg, France, where she was overhauled. Shortly after, a Union sloop-of-war, USS Kearsarge, arrived; and on June 19, the Battle of Cherbourg commenced outside the port of Cherbourg, France, whereby the Kearsarge sank the Alabama in approximately one hour after the Alabama's opening shot.

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]Alabama was built in secrecy in 1862 by British shipbuilders John Laird Sons and Company, in north-west England at their shipyards at Birkenhead, Wirral, opposite of the city of Liverpool. The construction was arranged by the Confederate agent Commander James Bulloch, who led the procurement of sorely needed ships for the fledgling Confederate States Navy.[5] The contract was arranged through the Fraser Trenholm Company, a cotton broker in Liverpool with ties to the Confederacy. Under prevailing British neutrality law, it was possible to build a ship designed as an armed vessel, provided that it was not actually armed until after it was in international waters. In light of this loophole, Alabama was built with reinforced decks for cannon emplacements, ammunition magazines below water level, etc., but was not fitted with armaments or any "warlike equipment" originally.

Initially known only by her shipyard number "ship number 0290", she was launched as Enrica on 15 May 1862 and secretly slipped out of Birkenhead on 29 July 1862.[6] U.S. Navy Commander Tunis A. M. Craven, commander of USS Tuscarora, was in Southampton and was tasked with intercepting the new ship, but was unsuccessful.[7] Agent Bulloch arranged for a civilian crew and captain to sail Enrica to Terceira Island in the Azores. With Bulloch accompanying him, the new ship's captain, Raphael Semmes, left Liverpool on 13 August 1862 aboard the steamer Bahama to take command of the new cruiser. Semmes arrived at Terceira Island on 20 August 1862 and began overseeing the refitting of the new vessel with various provisions, including armaments, and 350 tons of coal, brought there by Agrippina, his new ship's supply vessel. After three days of work by the three ships' crews, Enrica was equipped as a naval cruiser, designated a commerce raider, for the Confederate States of America. Following her commissioning as CSS Alabama, Bulloch then returned to Liverpool to continue his secret work for the Confederate Navy.[8]

Alabama's British-made ordnance consisted of six muzzle-loading, broadside, 32-pounder naval smoothbores (three firing to port and three firing to starboard) and two larger and more powerful pivot cannons. The pivot cannons were placed fore and aft of the main mast and positioned roughly amidships along the deck's center line. From those positions, they could be rotated to fire across the port or starboard sides of the cruiser. The fore pivot cannon was a heavy, long-range 100-pounder, 7-inch-bore (178 mm) Blakely rifled muzzleloader; the aft pivot cannon a large, 8-inch (203 mm) smoothbore.

The new Confederate cruiser was powered by both sail and by a two-cylinder John Laird Sons and Company 300 horsepower (220 kW) horizontal steam engine,[9][10] driving a single, Griffiths-type, twin-bladed brass screw. (Note: At the time a cylinder was also called an engine. Therefore, the machinery involved, which had two cylinders, could also be referred to as a pair of engines, which description is often found in sources.)

The telescopic funnel could be raised or lowered by chains to disguise the fact that the vessel was a steamer.[11]

With the screw retracted using the stern's brass lifting gear mechanism, Alabama could make up to ten knots under sail alone and 13.25 knots (24.54 km/h) when her sail and steam power were used together.

Commissioning and voyage

[edit]

The ship was purposely commissioned about a mile off Terceira Island in international waters on 24 August 1862. All the men from Agrippina and Bahama had been transferred to the quarterdeck of Enrica, where her 24 officers, some of them Southerners, stood in full dress uniform. Captain Raphael Semmes mounted a gun-carriage and read his commission from President Jefferson Davis, authorizing him to take command of the new cruiser. Upon completion of the reading, musicians assembled from among the three ships' crews began to play the tune "Dixie" as the quartermaster finished hauling down Enrica's British colors. A signal cannon was fired and the ship's new battle ensign and commissioning pennant were broken out at the peaks of the mizzen gaff and mainmast. With that the cruiser became the Confederate States Steamer Alabama. The ship's motto: Aide-toi et Dieu t'aidera (French which approximately translates as "God helps those who help themselves") was engraved in the bronze of the great double ship's wheel.[12]

Captain Semmes then made a speech about the Southern cause to the assembled seamen (few of whom were American), asking them to sign on for a voyage of unknown length and destiny. Semmes had only his 24 officers and no crew to man his new command. When this did not succeed, he offered signing money and double wages, paid in gold, and additional prize money to be paid by the Confederate congress for all destroyed Union ships. The men began to shout "Hear! Hear!" in response. 83 seamen, many of them British, signed on for service in the Confederate Navy. Bulloch and the remaining seamen then boarded their respective ships for the return to England. Semmes still needed another 20 or so men for a full complement, but there were enough to at least handle the new commerce raider. The rest would be recruited from the captured crews of raided ships or from friendly ports-of-call. Many of the 83 crewmen who signed on completed the full voyage.

Under Captain Semmes, Alabama spent her first two months in the Eastern Atlantic, ranging southwest of the Azores and then redoubed east, targeting northern merchant ships. After an Atlantic crossing, she continued her cruise in the greater New England region. She then sailed south, arriving in the West Indies, where she continued disrupting merchant vessels before finally cruising west into the Gulf of Mexico. There, in January 1863, Alabama had her first military engagement. She came upon and quickly sank the Union side-wheeler USS Hatteras just off the Texas coast, near Galveston, capturing that warship's crew.[citation needed] She then continued further south, eventually crossing the Equator, where she attained most of the successes of her raiding career while cruising off the coast of Brazil.[citation needed]

After a second, easterly Atlantic crossing, Alabama sailed down the southwestern African coast where she continued the campaign against northern commerce. After stopping in Saldanha Bay on 29 July 1863 in order to verify that no enemy ships were in Table Bay,[15] she made a refitting and reprovisioning visit to Cape Town, South Africa. Alabama is the subject of an Afrikaans folk song, "Daar kom die Alibama" .[16][17][18] She then sailed for the East Indies where she spent six months, destroying seven more ships before finally returning via the Cape of Good Hope en route to France. Alabama was often hunted for by Union warships; however, she was able to successfully evade engagement.[citation needed]

All together, she burned 65 Union vessels of various types, most of them merchant ships.

Expeditionary raids

[edit]

Alabama conducted a total of seven expeditionary raids, spanning the globe, before heading to France for refit and repairs:

- CSS Alabama's Eastern Atlantic Expeditionary Raid (August–September 1862) commenced immediately after commissioning. She set sail for the shipping lanes southwest and then east of the Azores, where she captured and burned ten ships, mostly whalers.

- CSS Alabama's New England Expeditionary Raid (October–November 1862) began after Captain Semmes and his crew departed for the northeastern seaboard of North America, along Newfoundland and New England, where she ranged as far south as Bermuda and the coast of Virginia, burning ten vessels while capturing and releasing three others.

- CSS Alabama's Gulf of Mexico Expeditionary Raid (December 1862 – January 1863) began as Alabama effected a needed rendezvous with her supply vessel, CSS Agrippina. Afterward, she provided support to Confederate land forces during the Battle of Galveston in coastal Texas, by sinking the Union side-wheeler USS Hatteras.

- CSS Alabama's South Atlantic Expeditionary Raid (February–July 1863) was her most successful raiding venture, taking 29 ships while raiding off the coast of Brazil. Here she recommissioned the bark Conrad as CSS Tuscaloosa.

- CSS Alabama's South African Expeditionary Raid (August–September 1863) occurred primarily while ranging off the coast of South Africa, as she worked together with CSS Tuscaloosa.

- CSS Alabama's Indian Ocean Expeditionary Raid (September–November 1863) involved a journey of nearly 4,500 miles (7,250 km) across the Indian Ocean.[19] Successfully evading the Union gunboat Wyoming, she took three ships near the Sunda Strait and the Java Sea.[20]

- CSS Alabama's South Pacific Expeditionary Raid (December 1863) was her final raiding venture. She took a few prizes in the Strait of Malacca before finally turning back toward France for refit and repair.[citation needed]

Upon the completion of her seven expeditionary raids, Alabama had been at sea for 534 days out of 657, never visiting a Confederate port. She boarded nearly 450 vessels, captured or burned 65 Union merchant ships, and took more than 2,000 prisoners without any loss of life among either prisoners or her own crew.[citation needed]

Final cruise

[edit]

On 11 June 1864, Alabama arrived in port at Cherbourg, France. Captain Semmes soon requested permission to dry dock and overhaul his ship, necessary after naval action and so long at sea. Pursuing the raider, the American sloop-of-war, USS Kearsarge, under the command of Captain John Ancrum Winslow, arrived three days later and took up station just outside the harbor. While at his previous port-of-call, Winslow had telegraphed Gibraltar to send the old sloop-of-war USS St. Louis with provisions and to provide blockading assistance. Kearsarge had now boxed in Alabama.

Up to this point, Semmes had faced another warship only once—the much less well armed blockade ship Hatteras. He believed that the Kearsarge was not superior to Alabama, and did not wish for his ship to be interned by the French.[21] Therefore, after preparing his ship and drilling the crew for the coming battle during the next several days, Semmes issued, through diplomatic channels, a challenge to the Kearsarge's commander,[22] "my intention is to fight the Kearsarge as soon as I can make the necessary arrangements. I hope these will not detain me more than until to-morrow or the morrow morning at farthest. I beg she will not depart until I am ready to go out. I have the honor to be Your obedient servant, R. Semmes, Captain."

On 19 June, Alabama sailed out to meet the Union cruiser. Jurist Tom Bingham later wrote, "The ensuing battle was witnessed by Édouard Manet, who went out to paint it, and the owner of an English yacht who had offered his children a choice between watching the battle and going to church."[23]

As Kearsarge turned to meet her opponent, Alabama opened fire. Kearsarge waited until the range had closed to less than 1,000 yards (900 m). According to combatants, the two ships steamed on opposite courses in seven spiraling circles, moving southwesterly with the 3-knot current, each commander trying to cross the bow of his opponent to deliver a heavy raking fire (to "cross the T"). The battle quickly turned against Alabama due to the superior gunnery displayed by Kearsarge and the deteriorated state of Alabama's contaminated powder and fuses. Her most telling shot, fired from the forward 7-inch (178 mm) Blakely pivot rifle, hit very near Kearsarge's vulnerable stern post, the impact binding the ship's rudder badly. That rifled shell, however, failed to explode. If it had done so, it would have seriously disabled Kearsarge's steering, possibly sinking the warship, and ending the contest. In addition, Alabama's too rapid rate-of-fire resulted in poor gunnery, with many of her shots going too high, and as a result Kearsarge's outboard chain armor received little damage. Semmes later said that he did not know about Kearsarge's armor at the time of his decision to issue the challenge to fight, and in the following years firmly maintained he would have never fought Kearsarge if he had known.

Kearsarge's hull armor had been installed in just three days, more than a year before, while she was in port at the Azores. It was made using 120 fathoms (720 ft; 220 m) of 1.7-inch (43 mm) single link iron chain and covered hull spaces 49 feet 6 inches (15.09 m) long by 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m) deep. It was stopped up and down to eye-bolts with marlines and secured by iron dogs. Her chain armor was concealed behind 1-inch deal-boards painted black to match the upper hull's color. This "chaincladding" was placed along Kearsarge's port and starboard midsection down to the waterline, for additional protection of her engine and boilers when the upper portion of her coal bunkers were empty (coal bunkers played an important part in the protection of early steam vessels, such as protected cruisers).

A hit to her engine or boilers could easily have left Kearsarge dead in the water, or even caused a boiler explosion or fire that could destroy the cruiser. Her armor belt was struck twice during the fight. The first hit, by one of Alabama's 32-pounder shells, was in the starboard gangway, cutting the chain armor and damaging the hull planking underneath. A second 32-pounder shell exploded and broke a link of the chain armor, tearing away a portion of the deal-board covering. Had those rounds come from Alabama's more powerful 100-pounder Blakely pivot rifle, they would have easily penetrated, but the likely result would not have been very serious, as both shots struck the hull a little more than five feet above the waterline. Even if both shots had penetrated Kearsarge's side, they would have missed her vital machinery. However, a 100-pound shell could have done a great deal of damage to her interior; hot fragments could have easily set fire to the cruiser, one of the greatest risks aboard a wooden vessel.

A little more than an hour after the first shot was fired, Alabama was reduced to a sinking wreck by Kearsarge's powerful 11-inch (280 mm) Dahlgrens, forcing Captain Semmes to strike his colors and to send one of his two surviving boats to Kearsarge to ask for assistance.

According to witnesses, Alabama fired about 370 rounds at her adversary, averaging one round per minute per gun, a fast rate of fire compared to Kearsarge's gun crews, who fired less than half that number, taking more careful aim. In the confusion of battle, five more rounds were fired at Alabama after her colors were struck. (Her gun ports had been left open and the broadside cannon were still run out, appearing to threaten Kearsarge.) A hand-held white flag at Alabama's stern spanker boom finally halted the engagement.

Prior to this, she had her steering gear damaged by shell hits, but the fatal shot came later when one of Kearsarge's 11-inch (280 mm) shells tore open a mid-section of Alabama's starboard waterline. Water quickly rushed through the hull, eventually flooding the boilers and taking her down by the stern to the bottom. As Alabama sank, the injured Semmes threw his sword into the sea, depriving Kearsarge's commander, Winslow, of the traditional surrender of the sword (an act which was seen as dishonorable by many at the time).

Of her 170 crew, the Alabama had 19 fatalities (9 killed and 10 drowned) and 21 wounded[24] Kearsarge rescued most of the survivors, but 41 of Alabama's officers and crew, including Semmes, were rescued by John Lancaster's private British steam yacht Deerhound, while Kearsarge stood off to recover her rescue boats as Alabama sank.[25] Captain Winslow had to stand by and watch Deerhound spirit his adversary away to England. Semmes and the 41 crew members successfully reached England. Semmes eventually returned to the Confederacy and became a Confederate admiral in the last weeks of the war.[26]

The sinking of Alabama by Kearsarge is honored by the United States Navy with a battle star on the Civil War campaign streamer.

Officers

[edit]

| Officers | |

|---|---|

| Officer | Post |

| List of Officers Of The Confederate States Steamer Alabama

As They Signed Themselves.[27] | |

| Raphael Semmes | Commander |

| John McIntosh Kell | First Lieutenant And Executive Officer |

| Richard F. Armstrong | Second Lieutenant |

| Joseph D. Wilson | Third Lieutenant |

| John Low | Fourth Lieutenant |

| Arthur Sinclair | Fifth Lieutenant |

| Francis L. Galt | Surgeon And Acting Paymaster |

| Miles J. Freeman | Chief-Engineer |

| Wm. P. Brooks | Assistant- Engineer |

| Mathew O Brien | Assistant-Engineer |

| Simeon W. Cummings[A] | Assistant-Engineer |

| John M. Pundt | Assistant-Engineer |

| Wm. Robertson[B] | Assistant-Engineer |

| Becket K. Howell[C] | Lieutenant Marines |

| Irvine S. Bulloch | Sailing-Master |

| D. Herbert Llewellyn[D] | Assistant-Surgeon |

| Wm. H. Sinclair | Midshipman |

| E. Anderson Maffitt | Midshipman |

| E. Maffitt Anderson | Midshipman |

| Benjamin P. Mecaskey | Boatswain |

| Henry Alcott | Sailmaker |

| Thomas C. Cuddy | Gunner |

| Wm. Robinson[E] | Carpenter |

| Jas. Evans | Master's Mate |

| Geo. T. Fullam | Master's Mate |

| Julius Schroeder | Master's Mate |

| Baron Max. Von Meulnier | Master's Mate |

| W. Breedlove Smith | Captain S Secretary |

- A Died in Saldanha Bay from accidental gunshot on 3 August 1863.[15]

- B Drowned in the sinking of the Alabama 19 June 1864.[28]

- C Lt of CS Marines. Brother-in-law of CS President Jefferson Davis

- D Drowned in the sinking of the Alabama 19 June 1864.[29]

- E Killed in action in the sinking of the Alabama 19 June 1864[28]

Dr. David Herbert Llewellyn, a Briton and the ship's assistant surgeon, tended the wounded during the battle. At one point the operating table was shot away.[30] He worked in the wardroom until the order to abandon ship was finally given. As he helped wounded men into Alabama's only two functional lifeboats, an able-bodied sailor attempted to enter one, which was already full. Llewellyn, understanding that the man risked capsizing the craft, grabbed and pulled him back, saying "See, I want to save my life as much as you do; but let the wounded men be saved first."

An officer in the boat, seeing that Llewellyn was about to be left aboard the stricken Alabama, shouted "Doctor, we can make room for you." Llewellyn shook his head and replied, "I will not peril the wounded." Unknown to the crew, Llewellyn had never learned to swim, and he drowned when the ship went down.

His sacrifice did not go unrecognized in England. In his native village, a memorial window and tablet were placed at Easton Royal Church.[31] Another tablet was placed in Charing Cross Hospital, London, where he attended medical school.

Repercussions

[edit]

During her two-year career as a commerce raider, Alabama damaged Union merchant shipping around the world. The Confederate cruiser claimed 65 prizes valued at nearly $6,000,000 (about $121,000,000 in today's dollars[32]); in 1862 alone 28 were claimed.[33] In an important development in international law, the U.S. government pursued the "Alabama Claims" against the United Kingdom for the losses caused by Alabama and other raiders fitted out there. A joint arbitration commission awarded the U.S. $15.5 million in damages.

Ironically, in 1851, a decade before the Civil War, Captain Semmes had observed:

(Commerce raiders) are little better than licensed pirates; and it behooves all civilized nations [...] to suppress the practice altogether.[34]

However, she and other raiders failed in their primary purpose, which was to draw Union vessels away from the blockade of the southern coastline that was slowly strangling the Confederacy. The Confederate government had hoped that panicking shipping companies would force the Union to dispatch ships to protect merchant shipping and hunt down the raiders, a task which always requires a proportionately greater force when compared with the numbers of ships attacking (see Battle of the Atlantic). Union officials proved immovable on the blockade, however, and although insurance prices soared, shipping costs went up, and many vessels transferred to a neutral flag, very few naval vessels were taken off the southern blockade. In fact, with clever use of resources and a mammoth shipbuilding program, the Union managed to steadily increase the blockade throughout the war. It also sent vessels to protect merchant shipping and to hunt and destroy the few Confederate raiders and privateers still operating.[citation needed]

The wreck

[edit]In November 1984 the French Navy mine hunter Circé discovered a wreck under nearly 200 ft (60 m) of water off Cherbourg[35] at 49°45′9″N 1°41′42″W / 49.75250°N 1.69500°W.[36] Captain Max Guerout later confirmed the wreck to be Alabama's remains.

In 1988 a non-profit organization, the CSS Alabama Association, was founded to conduct scientific exploration of the shipwreck. Although the wreck is in French territorial waters, the United States Government, as the successor to the former Confederate States of America, is the owner. On 3 October 1989 the US and France signed an agreement recognizing this wreck as an important heritage resource of both nations and establishing a Joint French-American Scientific Committee for archaeological exploration. This agreement established a precedent for international cooperation in archaeological research and in the protection of a unique historic shipwreck.

The Association CSS Alabama and the Naval History and Heritage Command signed on 23 March 1995 an official agreement accrediting Association CSS Alabama as operator of the archaeological investigation of the remains of the ship. The association, which is funded solely from private donations, is continuing to make this an international project through its fundraising in France and in the US, thanks to its sister organization, the CSS Alabama Association, incorporated in the State of Delaware.

Alabama was fitted with eight pieces of ordnance after she arrived at the Azores; six of those were 32-pounder smooth bores. Seven cannon were identified at the wreck site: Two were cast from a Royal Navy pattern and three were of a later pattern produced by Fawcett, Preston, and Company in Liverpool.

One of the Blakely pattern 32-pounders was found lying across the starboard side of the hull, forward of the boilers. A second Blakely 32-pounder was identified outside the hull structure, immediately forward of the propeller and its lifting frame; the forward 32-pounder was recovered in 2000. Both of the Royal Navy pattern 32-pounders were identified: One lies inside the starboard hull, forward of the boilers, adjacent to the forward Downton pump. The second was identified as lying on the iron deck structure, immediately aft of the smoke pipe; it was recovered in 2001. The sole remaining 32-pounder has not been positively identified, but it could be underneath hull debris forward of the starboard Trotman anchor.

Alabama's heavy ordnance were one Blakely Patent 7-inch 100-pounder shell rifle mounted on a pivot carriage forward and one 68-pounder smoothbore similarly mounted aft. The Blakely 7-inch 100-pounder was found beside its pivot carriage, atop the forward starboard boiler; this was the first cannon recovered from Alabama. The 68-pounder smoothbore was located aft, at the stern, immediately outside the starboard hull structure; it is possible that the remains of its truck and pivot carriage lie underneath the gun barrel. Both heavy cannon were recovered in 1994.

In addition to the seven cannon, the wreck site contained shot, gun truck wheels, and brass tracks for the gun carriages; many of the brass tracks were recovered. Two shot were recovered, and one conical projectile was inside the barrel of the 7-inch Blakely rifle. A shell for a 32-pounder was recovered from the stern, forward of the propeller; that shot was attached to a wood sabot having been packed in a wood box for storage. Additional round shot were observed scattered forward of the boilers and in the vicinity of the aft pivot gun, one possibly having been fired from Kearsarge.

In 2002, a diving expedition raised the ship's bell along with more than 300 other artifacts, including more cannons, structural samples, tableware, ornate commodes, and numerous other items that reveal much about life aboard the Confederate warship.[37] Many of the artifacts are now housed in the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Naval History & Heritage Command conservation lab.

Folklore and heritage

[edit]

Alabama is the subject of a sea shanty, "Roll, Alabama, Roll"[38][39] which was also the basis of a 2014 record of the same name by British contemporary folk band Bellowhead.

Alabama's visit to Cape Town in 1863 has passed (with a slight spelling change) into South African folklore in the Afrikaans song, Daar Kom die Alibama.[40][41][42]

The Alabama Hills in Inyo County, California, are named after the vessel.[43]

Claimed links between the CSS Alabama and Captain Nemo’s fictional submarine the Nautilus

[edit]In 1998, the Jules Verne scholar William Butcher was the first to identify a possible link between the Birkenhead-built Alabama and Captain Nemo’s Nautilus from the Jules Verne 1869 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas. Butcher stated The Alabama, which claimed to have sunk 75 merchantmen, was destroyed by the Unionist Kearsarge off Cherbourg on 11th June 1864…. This battle has clear connections with Nemo’s final attack, also in the English Channel.[44]

Verne had himself made a previous comparison between the Birkenhead-built CSS Alabama and the Nautilus in a letter to his publisher Jules Hetzel in March 1869.[45] Other arguments in favor of a connection were made by Birkenhead born geography teacher John Lamb.[46] Writing in the April 2025 edition of Foundation – The International Review of Science Fiction, John Lamb stated there were many links between the fictional Captain Nemo, the Nautilus and Raphael Semmes the Confederate Captain of the commerce raider CSS Alabama in the American Civil War. Lamb wrote

Both the Alabama and the Nautilus were mainly built in Birkenhead. Both Semmes and Nemo were gifted natural historians. Nemo’s motto was ‘Mobilis in Mobile’ while Semmes was from Mobile Alabama. Semmes was branded a pirate by Abraham Lincoln, who put a bounty on Semmes's head, and Semmes was chased around the seas by Admiral Farragut of the US Navy. Nemo, conversely, was branded a pirate by Captain Farragut of the US Navy, who put a bounty on Nemo's head, and Nemo was chased around the seas by the ship Abraham Lincoln. Both Semmes and Nemo encounter an imaginary island, sail through a patch of white water, encounter fake Havana cigars, mention coral mausoleums, shelter in an extinct volcanic island, and have their final battle off Cherbourg. Semmes had a portrait of the Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, in his cabin while Nemo had a portrait of the Union President, Abraham Lincoln, in his. The Alabama was bankrolled from the Confederate headquarters at Nautilus House Liverpool.[47]

Battle ensigns and other naval flags

[edit]Both the United States Navy and the Confederate States Navy flew an ensign and a jack (primary and secondary naval flags) following British naval tradition that originated in the 17th century.[48][49] The fledgling Confederate Navy therefore adopted and used jacks, commissioning pennants, battle ensigns, small boat ensigns, designating flags, and signal flags aboard its warships during the Civil War.[50]

Surviving flags

[edit]

At the beginning of Alabama's raiding ventures, the newly commissioned cruiser may have been forced, out of necessity, to fly the only battle ensign available to Captain Semmes: an early 1861, 7-star First National Flag, possibly the same battle ensign flown aboard his previous command, the smaller commerce raider CSS Sumter. Between 21 May and 28 November 1861, six more Southern states seceded and joined the Confederacy. Well before Alabama was launched as Enrica at Birkenhead, Merseyside in North West England, six more white, 5-pointed stars had been added to the "Stars and Bars" far away across the Atlantic on the Confederate mainland.[citation needed]

One such early "Stars and Bars" battle ensign was salvaged from Alabama's floating debris, following her sinking by Kearsarge. It still survives and is held by the Alabama Department of Archives and History. It is listed there as "Auxiliary Flag of the C.S.S. Alabama, Catalogue No. 86.3766.1." According to their provenance reconstruction, DeCost Smith, an American from New England, discovered this "Stars and Bars" ensign in a Paris upholstery shop in 1884, where he purchased it for 15 francs. Smith's nephew, Clement Sawtell of Lincoln Square, Massachusetts, later inherited the ensign from his uncle. At the suggestion of retired Rear Admiral Beverly M. Coleman, Sawtell donated it to the State of Alabama on 3 June 1975.[citation needed]

This battle ensign's overall dimensions are different from the Confederate flag regulations' required 2:3 ratio. It is 64-inches high (hoist) by 112-inches long (fly), a proportion of 5:9, and its dark blue canton contains eight white stars, 8-inches (203 mm) high, in an unusual arrangement: The stars are not organized in a circle but configured in three, centered, horizontal rows of two, then three, and finally two. The additional 8th star is tucked into the lower left corner (and in the lower right corner on the opposite side), giving the canton's layout a unique, asymmetrical appearance. It seems plausible this was Alabama's original 7-star battle ensign, possibly flown aboard CSS Sumter as noted earlier, and later altered at some point when the long-delayed news of an 8th state joining the Confederacy finally reached the far distant cruiser.[citation needed]

Two "Star and Bars" battle ensigns, labeled as having belonged to Alabama, also still exist. The first is a mounted and framed, 14-star ensign located at the Mariner's Museum in Virginia. (A small number of these unusual 14-star national flags have survived to the modern era and are held in several Civil War archives.) From the several color photo available on the Internet, this ensign appears to have an approximate hoist-to-fly aspect ratio of 1:2.5 (i.e., very rectangular). A second "Stars and Bars" battle ensign is on display at the Pensacola Historical Museum. Its canton contains a circle of 12 stars surrounding a centered, larger 13th star.[citation needed]

Surviving stainless banners

[edit]Four of Alabama's later-style ensigns have survived to the modern era. The first measures 67 in × 114 in (170 cm × 290 cm) and is located in South Africa at Cape Town's Bo-Kaap Museum. Its Southern Cross canton is oversize and made after the British navy fashion: Instead of being square, it has a very rectangular 1:2 aspect ratio. It was also made without any white stripes outlining its diagonal blue bars. A central 5-pointed white star, located where the two blue saltires' cross, is larger than the other twelve. This ensign appears to have been made by her British crew sometime between Alabama's two visits to Cape Town. This flown ensign was finally given in thanks to William Anderson, whose ship's chandler company helped make repairs and provide supplies to Alabama in Cape Town, shortly before the raider returned to Cherbourg, France (and her fateful battle with the sloop-of-war, USS Kearsarge).

A second Stainless Banner ensign of South African origin was made and then presented to Alabama on one of her two port visits to Cape Town; it resides in the Tennessee State Museum, according to their website.

The third surviving Stainless Banner is one of Alabama's original small boat ensigns. This official-looking 25.5 in × 41 in (65 cm × 104 cm) ensign is marked in brown pigment on its hoist: "Alabama. 290. C.S.N. 1st Cutter." In 2007 it was offered and sold through Philip Weiss Auctions. It was being sold by the grandson of its second owner, who had originally purchased it from the granddaughter of a USS Kearsarge sailor. Its buyer has since resold this small boat ensign through a later auction.

A fourth surviving ensign appears, from various clues observed in on-line photos, to be roughly 36 in × 54 in (91 cm × 137 cm). Because Alabama was forced to replace several of her original small boats lost at different times during her lengthy cruise, this is likely a larger replacement boat ensign. While it could have been made aboard, its somewhat more accurate details suggest it might have been commissioned ashore during a port-of-call visit. This ensign was rescued from the sinking Alabama by W. P. Brooks, the cruiser's assistant-engineer. It was last flown, along with other historic flags, during a ceremony held on the parade ground at Fort Pulaski, GA, sometime during 1937. This ensign has since been mounted and framed and continues to reside with the Brooks family; four modern photos of it can be found at the website for the "Alabama Crew," a British-based naval reenactor group.

The Alabama Department of Archives and History has in its collection one more important Stainless Banner ensign listed as "Admiral Semmes' Flag, Catalogue No. 86.1893.1 (PN10149-10150)". Their provenance reconstruction shows that it was presented to Semmes after the sinking of Alabama by "Lady Dehogton and other English ladies". Such presentations of ceremonial colors were uncommon to ships' captains of the Confederate Navy, but a few were known to have received such honors. This Second National Flag is huge and made of pure silk, giving it an elegant appearance. While this ensign is in a remarkable state of preservation, its large size and delicate condition have made its up-close details and measurements unavailable. When Semmes returned to the Confederacy from England, he brought this ceremonial Stainless Banner with him. It was inherited by his grandchildren, Raphael Semmes III and Mrs. Eunice Semmes Thorington. Following his sister's death, Raphael Semmes III donated the ensign to the state of Alabama on 19 September 1929.

See also

[edit]- Irvine Bulloch – James's half-brother who was the youngest midshipman and officer on the ship

- James Dunwoody Bulloch – Confederate agent and uncle of Theodore Roosevelt who covertly bought the Alabama

- Blockade runners of the American Civil War

- Bibliography of American Civil War naval history

- List of ships captured in the 19th century

- List of ships of the Confederate States Navy

- Trent Affair

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "C.S.S. Alabama Artifacts Exhibit at U.S. Naval Museum opens with All-Star Franco-American Reception" (PDF). The Confederate Naval Historical Society Newsletter Issue Number Nine. The Confederate Naval Historical Society. February 1992. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ a b Fletcher, R.A. (1910). Steam-ships : the story of their development to the present day. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. pp. 175–176. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ Kinnaman, Stephen C. (2 June 2023). "Technical Report—Inside the Alabama". U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ "The Alabama". Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

- ^ Fox, Stephen (2008). Wolf of the Deep Raphael Semmes and the Notorious Confederate Raider CSS Alabama. United States: Vintage Civil War Library. p. 7. ISBN 9781400095421.

- ^ Wilson, Walter E. and Gary L. McKay (2012). "James D. Bulloch; Secret Agent and Mastermind of the Confederate Navy". Jefferson, NC: McFarland, pp. 76, 80

- ^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 381.

- ^ Wilson, Walter E. and Gary L. McKay (2012). "James D. Bulloch; Secret Agent and Mastermind of the Confederate Navy". Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 90-92

- ^ "English Accounts", The New York Times, 1864-07-06.

- ^ Bowcock, Andrew. CSS Alabama, Anatomy of a Confederate Raider, Chatham Publishing, London, 2002. ISBN 1-86176-189-9. p. 139.

- ^ Bowcock, Andrew. CSS Alabama, Anatomy of a Confederate Raider Chatham Publishing, London, 2002. ISBN 1-86176-189-9. p. 179.

- ^ Watts Jr., Gordon P. "Archaeological Investigation of the Confederate Commerce Raider CSS Alabama 2002". Historic Naval Ships Association. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ^ Sinclair, Arthur, Lt. CSN (1896). Two Years on the Alabama. Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "CSS Alabama (1862-1864) - Selected Views". U.S. Naval Historical Center. 12 July 2000. Archived from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ a b Green, Lawrence. "20 – Lloyed of the Lagoon". In the Land Of Afternoon. pp. 280–281. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ Civil War Times Illustrated. Historical Times, Incorporated. 1991.

- ^ Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr.; Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong; Mr. Steven J. Niven (2 February 2012). Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- ^ Walker, Gary (1994). Civil War Tales. Pelican Publishing. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-1-4556-0231-5.

- ^ Fox, p. 179

- ^ Fox, pp. 180, 182, 183

- ^ "Kearsarge and Alabama". American Battlefield Trust. August 2017.

- ^ The Magazine of History with Notes ... – Google Book Search. 1907. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- ^ Bingham, Tom (2005). "The Alabama Claims Arbitration". The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 54 (1). Cambridge University Press: 7. doi:10.1093/iclq/54.1.1. JSTOR 3663355.

- ^ Kell, John McIntosh (1887). Johnson, Robert Underwood; Buel, Clarence Clough (eds.). Cruise and Combats of the "Alabama". Vol. Four. New York: Century Co. p. 614. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Crocker III, H. W. (2006). Don't Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. pp. 216. ISBN 978-1-4000-5363-6.

- ^ Barnett, "Alabama," 105.

- ^ Sinclair, Arthur, Lt. CSN (1896). Two Years on the Alabama. Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers. pp. 343.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "CSS Alabama Association (USA) - The Crew". css-alabama.com.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com.

- ^ Kell, John McIntosh (1887). Johnson, Robert Underwood; Buel, Clarence Clough (eds.). Cruise and Combats of the "Alabama". Battles and leaders of the Civil War. Vol. Four. New York: Century Co. p. 611. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Baker, Mark (1973). "David Herbert Llewellyn 1837-1864". Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine. 68 (B): 110.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of the Holy Trinity, Easton Royal (1364554)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Appleton's Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events of the Year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 600.

- ^ Semmes, Raphael. Service Afloat and Ashore During the Mexican War. Cincinnati, OH: Wm. H. Moore & Co., 1851, pp. 80-82

- ^ Sciboz, Bertrand. "épave de l'Alabama / wreck of the Alabama/ Cherbourg 1864". Archived from the original on 19 September 2000.

- ^ More accurate location shown at: nautical chart Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shaffer, Caitlin (July 2008). "The CSS Alabama Dishes". Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum - State Museum of Archaeology. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Bennett, Marek (2016). "Roll, Alabama, Roll". The Hardtacks.

- ^ "Origins: Roll, Alabama Roll". The Mudcat Café. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ "South African Scout Campfire songbook: South African songs". South African Scout Association. 2008. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ van Niekerk JJ (1 January 2007). "The story of the CSS ("Daar kom die...") Alabama: some legal aspects of her visit to the Cape of Good Hope, and her influence on the historical development of the law of war and neutrality, international arbitration, salvage and maritime prize". Fundamina: A Journal of Legal History. 13 (2): 175–250. hdl:10.10520/EJC-72bece40b.

- ^ Duby, Marc (2 January 2014). "Alweer "die Alibama"? Reclaiming indigenous knowledge through a Cape Jazz lens". Muziki. 11 (1): 99–117. doi:10.1080/18125980.2014.893101. ISSN 1812-5980. S2CID 153555180.

- ^ Kyle, Douglas E. and Hoover, Mildred Brooke (1990). Historic Spots in California, p. 122. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4483-1.

- ^ William Butcher Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas - Jules Verne - Google Books Explanatory Notes Page 422 ISBN 0-19-282839-8

- ^ Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas - Jules Verne - Google Books Explanatory Notes Page 422 ISBN 0-19-282839-8

- ^ "Jules Verne and the Heroes of Birkenhead. Part 31" (PDF). julesverneandtheheroesofbirkenhead.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Foundation. The International Review of Science Fiction (April 2025). P116-127.

- ^ "Navy Ensigns, Pennants, and Jacks, 1861-1863". Confederate Flags. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ "History of British Naval Ensigns Part 1 (Great Britain)". www.crwflags.com. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ "Flags of the Confederate States Navy". Confederate Flags. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

Bibliography

- This article contains public domain material from the Naval History and Heritage Command, entry here.

- Barnett, Gene. "Alabama," Dictionary of American History, Volume 1, Third Edition.

- Bowcock, Andrew (2002) CSS Alabama, Anatomy of a Confederate Raider. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-189-9.

- D'Aubigny, Michel (1988). "Question 30/86". Warship International. XXV (4): 422. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Delaney, Norman C. "'Old Beeswax': Raphael Semmes of the Alabama."

Harrisburg, PA, Vol. 12, #8, December, 1973 issue, Civil War Times Illustrated. No ISSN. - Fox, Stephen (2007) Wolf of the Deep; Raphael Semmes and the Notorious Confederate Raider CSS Alabama. Nrw York: Alfred A. Knopf Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4000-4429-0.

- Gindlesperger, James (2005) Fire on the Water: The USS Kearsarge and the CSS Alabama. Burd Street Press. ISBN 978-1-57249-378-0.

- Hearn, Chester G. (1996) Gray Raiders of the Sea Baton Touge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2114-2.

- Luraghi, Raimondo (1996) A History of the Confederate Navy. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-527-6.

- Madaus, H. Michael (1986) Rebel Flags Afloat: A Survey of the Surviving Flags of the Confederate States Navy, Revenue Service, and Merchant Marine. Winchester, Massachusetts: Flag Research Center. ISSN 0015-3370.

- An 80-page special edition of "The Flag Bulletin" magazine, #115, devoted entirely to Confederate naval flags.

- Marvel, William (1996) The Alabama & the Kearsarge: The Sailor's War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2294-9.

- Roberts, Arthur C., M. D. "Reconstructing USS Kearsarge, 1864," Silver Spring, MD., Vol. 44, #4; Vol. 45, #s 1, 2, and 3, 1999, 2000,

Nautical Research Journal. ISSN 0738-7245. - Secretary of the Navy (1864) Sinking of the Alabama – Destruction of the Alabama by the Kearsarge. Washington, D.C., Navy Yard.

- Annual report in the library of the Naval Historical Center.

- Semmes, R., CSS, Commander (1864) The Cruise of the Alabama and the Sumter. New York: Carlton.

- Semmes, Raphael, Admiral, CSN (1987) Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War Between the States. Blue & Grey Press. ISBN 1-55521-177-1.

- Sinclair, Arthur, Lt. CSN (1896). Two Years on the Alabama. Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Still Jr., William N.; Taylor, John M.; Delaney, Norman C. (1998) Raiders and Blockaders, the American Civil War Afloat. Brassy's, Inc., ISBN 1-57488-164-7.

- Styles, Showell (1966) Number Two-ninety.

- fiction

- Staff (c.1937) "Confederate Flag Flies At Pulaski",Savannah News-Press, Savannah, Georgia.

- Depression-era newspaper article about W. P. Brooks' rescued CSS Alabama ensign being flown as part of a ceremony held on the parade ground at Fort Pulaski, Georgia

- Wilson, Walter E. and Gary L. Mckay (2012) James D. Bulloch; Secret Agent and Mastermind of the Confederate Navy. Mcfarland & Co. Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-6659-7.

External links

[edit]- Cruisers, Cotton and Confederates

- Semmes, Raphael, The Cruise of the Alabama and the Sumter, Carleton, 1864, Digitized by Digital Scanning Incorporated, 2001, ISBN 1-58218-353-8.

- C.S.S. Alabama: A Virtual Exhibit, Marshall University Archived 20 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Edwin Maffitt Anderson photographs (University Libraries Division of Special Collections, The University of Alabama) - photo album containing cartes de visite of Raphael Semmes and crew members, as well as drawings of the ship.

- “High Seas Duel” from Civil War Quarterly magazine, 2014. Numerous photos and first-hand accounts.

CSS Alabama

View on GrokipediaDesign and Construction

Technical Specifications

The CSS Alabama was a wooden-hulled, screw sloop-of-war with barkentine rigging, designed for speed and long-range cruising as a commerce raider. Her hull was constructed of oak and teak, copper-sheathed for protection against marine growth, enabling extended operations without frequent docking.[9] Key dimensions included a length overall of 213 feet 8 inches, an extreme beam of 32 feet, a depth of hold of 18 feet, and a fully loaded draft of 15 feet. Displacement reached 1,438 tons when fully loaded.[9] Alternative measurements cite a deck length of 220 feet with the same beam and loaded draft.[3] Propulsion combined sail and steam power. She featured two direct-acting, horizontal condensing engines with twin cylinders, rated at 300 horsepower total, driving a single lifting screw propeller that could be hoisted clear of the water for sailing efficiency. Four boilers supported steam operations, with a coal capacity of 285 tons allowing for extended voyages. Under steam alone, she achieved about 10 knots; combined sail and steam yielded up to 13 knots, with a designed maximum of 12 knots and ordinary service speed of 10 knots.[9][3]| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Armament | 1 × 7-inch (100-pounder) Blakely rifled pivot gun (forecastle); 1 × 8-inch (68-pounder) smoothbore pivot gun (quarterdeck); 6 × 32-pounder broadside guns on wheeled carriages |

| Crew Complement | Approximately 110 to 144 personnel, including 24 to 25 officers and 85 to 120 enlisted seamen |