Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

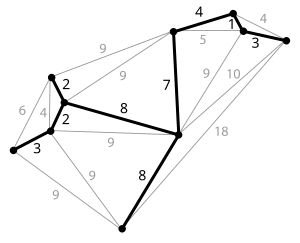

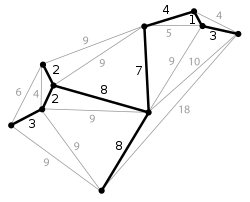

Minimum spanning tree

View on Wikipedia

A minimum spanning tree (MST) or minimum weight spanning tree is a subset of the edges of a connected, edge-weighted undirected graph that connects all the vertices together, without any cycles and with the minimum possible total edge weight.[1] That is, it is a spanning tree whose sum of edge weights is as small as possible.[2] More generally, any edge-weighted undirected graph (not necessarily connected) has a minimum spanning forest, which is a union of the minimum spanning trees for its connected components.

There are many use cases for minimum spanning trees. One example is a telecommunications company trying to lay cable in a new neighborhood. If it is constrained to bury the cable only along certain paths (e.g. roads), then there would be a graph containing the points (e.g. houses) connected by those paths. Some of the paths might be more expensive, because they are longer, or require the cable to be buried deeper; these paths would be represented by edges with larger weights. Currency is an acceptable unit for edge weight – there is no requirement for edge lengths to obey normal rules of geometry such as the triangle inequality. A spanning tree for that graph would be a subset of those paths that has no cycles but still connects every house; there might be several spanning trees possible. A minimum spanning tree would be one with the lowest total cost, representing the least expensive path for laying the cable.

Properties

[edit]Possible multiplicity

[edit]If there are n vertices in the graph, then each spanning tree has n − 1 edges.

There may be several minimum spanning trees of the same weight; in particular, if all the edge weights of a given graph are the same, then every spanning tree of that graph is minimum.

Uniqueness

[edit]If each edge has a distinct weight then there will be only one, unique minimum spanning tree. This is true in many realistic situations, such as the telecommunications company example above, where it's unlikely any two paths have exactly the same cost. This generalizes to spanning forests as well.

Proof:

- Assume the contrary, that there are two different MSTs A and B.

- Since A and B differ despite containing the same nodes, there is at least one edge that belongs to one but not the other. Among such edges, let e1 be the one with least weight; this choice is unique because the edge weights are all distinct. Without loss of generality, assume e1 is in A.

- As B is an MST, {e1} ∪ B must contain a cycle C with e1.

- As a tree, A contains no cycles, therefore C must have an edge e2 that is not in A.

- Since e1 was chosen as the unique lowest-weight edge among those belonging to exactly one of A and B, the weight of e2 must be greater than the weight of e1.

- As e1 and e2 are part of the cycle C, replacing e2 with e1 in B therefore yields a spanning tree with a smaller weight.

- This contradicts the assumption that B is an MST.

More generally, if the edge weights are not all distinct then only the (multi-)set of weights in minimum spanning trees is certain to be unique; it is the same for all minimum spanning trees.[3]

Minimum-cost subgraph

[edit]If the weights are positive, then a minimum spanning tree is, in fact, a minimum-cost subgraph connecting all vertices, since if a subgraph contains a cycle, removing any edge along that cycle will decrease its cost and preserve connectivity.

Cycle property

[edit]For any cycle C in the graph, if the weight of an edge e of C is larger than any of the individual weights of all other edges of C, then this edge cannot belong to an MST.

Proof: Assume the contrary, i.e. that e belongs to an MST T1. Then deleting e will break T1 into two subtrees with the two ends of e in different subtrees. The remainder of C reconnects the subtrees, hence there is an edge f of C with ends in different subtrees, i.e., it reconnects the subtrees into a tree T2 with weight less than that of T1, because the weight of f is less than the weight of e.

Cut property

[edit]

For any cut C of the graph, if the weight of an edge e in the cut-set of C is strictly smaller than the weights of all other edges of the cut-set of C, then this edge belongs to all MSTs of the graph.

Proof: Assume that there is an MST T that does not contain e. Adding e to T will produce a cycle, that crosses the cut once at e and crosses back at another edge e'. Deleting e' we get a spanning tree T∖{e' } ∪ {e} of strictly smaller weight than T. This contradicts the assumption that T was a MST.

By a similar argument, if more than one edge is of minimum weight across a cut, then each such edge is contained in some minimum spanning tree.

Minimum-cost edge

[edit]If the minimum cost edge e of a graph is unique, then this edge is included in any MST.

Proof: if e was not included in the MST, removing any of the (larger cost) edges in the cycle formed after adding e to the MST, would yield a spanning tree of smaller weight.

Contraction

[edit]If T is a tree of MST edges, then we can contract T into a single vertex while maintaining the invariant that the MST of the contracted graph plus T gives the MST for the graph before contraction.[4]

Algorithms

[edit]In all of the algorithms below, m is the number of edges in the graph and n is the number of vertices.

Classic algorithms

[edit]The first algorithm for finding a minimum spanning tree was developed by Czech scientist Otakar Borůvka in 1926 (see Borůvka's algorithm). Its purpose was an efficient electrical coverage of Moravia. The algorithm proceeds in a sequence of stages. In each stage, called Boruvka step, it identifies a forest F consisting of the minimum-weight edge incident to each vertex in the graph G, then forms the graph G1 = G \ F as the input to the next step. Here G \ F denotes the graph derived from G by contracting edges in F (by the Cut property, these edges belong to the MST). Each Boruvka step takes linear time. Since the number of vertices is reduced by at least half in each step, Boruvka's algorithm takes O(m log n) time.[4]

A second algorithm is Prim's algorithm, which was invented by Vojtěch Jarník in 1930 and rediscovered by Prim in 1957 and Dijkstra in 1959. Basically, it grows the MST (T) one edge at a time. Initially, T contains an arbitrary vertex. In each step, T is augmented with a least-weight edge (x,y) such that x is in T and y is not yet in T. By the Cut property, all edges added to T are in the MST. Its run-time is either O(m log n) or O(m + n log n), depending on the data-structures used.

A third algorithm commonly in use is Kruskal's algorithm, which also takes O(m log n) time.

A fourth algorithm, not as commonly used, is the reverse-delete algorithm, which is the reverse of Kruskal's algorithm. Its runtime is O(m log n (log log n)3).

All four of these are greedy algorithms. Since they run in polynomial time, the problem of finding such trees is in FP, and related decision problems such as determining whether a particular edge is in the MST or determining if the minimum total weight exceeds a certain value are in P.

Faster algorithms

[edit]Several researchers have tried to find more computationally-efficient algorithms.

In a comparison model, in which the only allowed operations on edge weights are pairwise comparisons, Karger, Klein & Tarjan (1995) found a linear time randomized algorithm based on a combination of Borůvka's algorithm and the reverse-delete algorithm.[5][6]

The fastest non-randomized comparison-based algorithm with known complexity, by Bernard Chazelle, is based on the soft heap, an approximate priority queue.[7][8] Its running time is O(m α(m,n)), where α is the classical functional inverse of the Ackermann function. The function α grows extremely slowly, so that for all practical purposes it may be considered a constant no greater than 4; thus Chazelle's algorithm takes very close to linear time.

Linear-time algorithms in special cases

[edit]Dense graphs

[edit]If the graph is dense (i.e. m/n ≥ log log log n), then a deterministic algorithm by Fredman and Tarjan finds the MST in time O(m).[9] The algorithm executes a number of phases. Each phase executes Prim's algorithm many times, each for a limited number of steps. The run-time of each phase is O(m + n). If the number of vertices before a phase is n', the number of vertices remaining after a phase is at most . Hence, at most log*n phases are needed, which gives a linear run-time for dense graphs.[4]

There are other algorithms that work in linear time on dense graphs.[7][10]

Integer weights

[edit]If the edge weights are integers represented in binary, then deterministic algorithms are known that solve the problem in O(m + n) integer operations.[11] Whether the problem can be solved deterministically for a general graph in linear time by a comparison-based algorithm remains an open question.

Planar graphs

[edit]Deterministic algorithms are known that solve the problem for planar graphs in linear time.[12][13] By the Euler characteristic of planar graphs, m ≤ 3n - 6 ∈ O(n), so this is in time O(n).

Decision trees

[edit]Given graph G where the nodes and edges are fixed but the weights are unknown, it is possible to construct a binary decision tree (DT) for calculating the MST for any permutation of weights. Each internal node of the DT contains a comparison between two edges, e.g. "Is the weight of the edge between x and y larger than the weight of the edge between w and z?". The two children of the node correspond to the two possible answers "yes" or "no". In each leaf of the DT, there is a list of edges from G that correspond to an MST. The runtime complexity of a DT is the largest number of queries required to find the MST, which is just the depth of the DT. A DT for a graph G is called optimal if it has the smallest depth of all correct DTs for G.

For every integer r, it is possible to find optimal decision trees for all graphs on r vertices by brute-force search. This search proceeds in two steps.

A. Generating all potential DTs

- There are different graphs on r vertices.

- For each graph, an MST can always be found using r(r − 1) comparisons, e.g. by Prim's algorithm.

- Hence, the depth of an optimal DT is less than r2.

- Hence, the number of internal nodes in an optimal DT is less than .

- Every internal node compares two edges. The number of edges is at most r2 so the different number of comparisons is at most r4.

- Hence, the number of potential DTs is less than

B. Identifying the correct DTs To check if a DT is correct, it should be checked on all possible permutations of the edge weights.

- The number of such permutations is at most (r2)!.

- For each permutation, solve the MST problem on the given graph using any existing algorithm, and compare the result to the answer given by the DT.

- The running time of any MST algorithm is at most r2, so the total time required to check all permutations is at most (r2 + 1)!.

Hence, the total time required for finding an optimal DT for all graphs with r vertices is:[4]

which is less than

Optimal algorithm

[edit]Seth Pettie and Vijaya Ramachandran have found a provably optimal deterministic comparison-based minimum spanning tree algorithm.[4] The following is a simplified description of the algorithm.

- Let r = log log log n, where n is the number of vertices. Find all optimal decision trees on r vertices. This can be done in time O(n) (see Decision trees above).

- Partition the graph to components with at most r vertices in each component. This partition uses a soft heap, which "corrupts" a small number of the edges of the graph.

- Use the optimal decision trees to find an MST for the uncorrupted subgraph within each component.

- Contract each connected component spanned by the MSTs to a single vertex, and apply any algorithm which works on dense graphs in time O(m) to the contraction of the uncorrupted subgraph

- Add back the corrupted edges to the resulting forest to form a subgraph guaranteed to contain the minimum spanning tree, and smaller by a constant factor than the starting graph. Apply the optimal algorithm recursively to this graph.

The runtime of all steps in the algorithm is O(m), except for the step of using the decision trees. The runtime of this step is unknown, but it has been proved that it is optimal - no algorithm can do better than the optimal decision tree. Thus, this algorithm has the peculiar property that it is provably optimal although its runtime complexity is unknown.

Parallel and distributed algorithms

[edit]Research has also considered parallel algorithms for the minimum spanning tree problem. With a linear number of processors it is possible to solve the problem in O(log n) time.[14][15]

The problem can also be approached in a distributed manner. If each node is considered a computer and no node knows anything except its own connected links, one can still calculate the distributed minimum spanning tree.

MST on complete graphs with random weights

[edit]Alan M. Frieze showed that given a complete graph on n vertices, with edge weights that are independent identically distributed random variables with distribution function satisfying , then as n approaches +∞ the expected weight of the MST approaches , where is the Riemann zeta function (more specifically is Apéry's constant). Frieze and Steele also proved convergence in probability. Svante Janson proved a central limit theorem for weight of the MST.

For uniform random weights in , the exact expected size of the minimum spanning tree has been computed for small complete graphs.[16]

| Vertices | Expected size | Approximate expected size |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1/2

|

0.5 |

| 3 | 3/4

|

0.75 |

| 4 | 31/35

|

0.8857143 |

| 5 | 893/924

|

0.9664502 |

| 6 | 278/273

|

1.0183151 |

| 7 | 30739/29172

|

1.053716 |

| 8 | 199462271/184848378

|

1.0790588 |

| 9 | 126510063932/115228853025

|

1.0979027 |

Fractional variant

[edit]There is a fractional variant of the MST, in which each edge is allowed to appear "fractionally". Formally, a fractional spanning set of a graph (V,E) is a nonnegative function f on E such that, for every non-trivial subset W of V (i.e., W is neither empty nor equal to V), the sum of f(e) over all edges connecting a node of W with a node of V\W is at least 1. Intuitively, f(e) represents the fraction of e that is contained in the spanning set. A minimum fractional spanning set is a fractional spanning set for which the sum is as small as possible.

If the fractions f(e) are forced to be in {0,1}, then the set T of edges with f(e)=1 are a spanning set, as every node or subset of nodes is connected to the rest of the graph by at least one edge of T. Moreover, if f minimizes, then the resulting spanning set is necessarily a tree, since if it contained a cycle, then an edge could be removed without affecting the spanning condition. So the minimum fractional spanning set problem is a relaxation of the MST problem, and can also be called the fractional MST problem.

The fractional MST problem can be solved in polynomial time using the ellipsoid method.[17]: 248 However, if we add a requirement that f(e) must be half-integer (that is, f(e) must be in {0, 1/2, 1}), then the problem becomes NP-hard,[17]: 248 since it includes as a special case the Hamiltonian cycle problem: in an -vertex unweighted graph, a half-integer MST of weight can only be obtained by assigning weight 1/2 to each edge of a Hamiltonian cycle.

Other variants

[edit]

- The Steiner tree of a subset of the vertices is the minimum tree that spans the given subset. Finding the Steiner tree is NP-complete.[18]

- The k-minimum spanning tree (k-MST) is the tree that spans some subset of k vertices in the graph with minimum weight.

- A set of k-smallest spanning trees is a subset of k spanning trees (out of all possible spanning trees) such that no spanning tree outside the subset has smaller weight.[19][20][21] (Note that this problem is unrelated to the k-minimum spanning tree.)

- The Euclidean minimum spanning tree is a spanning tree of a graph with edge weights corresponding to the Euclidean distance between vertices which are points in the plane (or space).

- The rectilinear minimum spanning tree is a spanning tree of a graph with edge weights corresponding to the rectilinear distance between vertices which are points in the plane (or space).

- The distributed minimum spanning tree is an extension of MST to the distributed model, where each node is considered a computer and no node knows anything except its own connected links. The mathematical definition of the problem is the same but there are different approaches for a solution.

- The capacitated minimum spanning tree is a tree that has a marked node (origin, or root) and each of the subtrees attached to the node contains no more than c nodes. c is called a tree capacity. Solving CMST optimally is NP-hard,[22] but good heuristics such as Esau-Williams and Sharma produce solutions close to optimal in polynomial time.

- The degree-constrained minimum spanning tree is a MST in which each vertex is connected to no more than d other vertices, for some given number d. The case d = 2 is a special case of the traveling salesman problem, so the degree constrained minimum spanning tree is NP-hard in general.

- An arborescence is a variant of MST for directed graphs. It can be solved in time using the Chu–Liu/Edmonds algorithm.

- A maximum spanning tree is a spanning tree with weight greater than or equal to the weight of every other spanning tree. Such a tree can be found with algorithms such as Prim's or Kruskal's after multiplying the edge weights by −1 and solving the MST problem on the new graph. A path in the maximum spanning tree is the widest path in the graph between its two endpoints: among all possible paths, it maximizes the weight of the minimum-weight edge.[23] Maximum spanning trees find applications in parsing algorithms for natural languages[24] and in training algorithms for conditional random fields.

- The dynamic MST problem concerns the update of a previously computed MST after an edge weight change in the original graph or the insertion/deletion of a vertex.[25][26][27]

- The minimum labeling spanning tree problem is to find a spanning tree with least types of labels if each edge in a graph is associated with a label from a finite label set instead of a weight.[28]

- A bottleneck edge is the highest weighted edge in a spanning tree. A spanning tree is a minimum bottleneck spanning tree (or MBST) if the graph does not contain a spanning tree with a smaller bottleneck edge weight. A MST is necessarily a MBST (provable by the cut property), but a MBST is not necessarily a MST.[29][30]

- A minimum-cost spanning tree game is a cooperative game in which the players have to share among them the costs of constructing the optimal spanning tree.

- The optimal network design problem is the problem of computing a set, subject to a budget constraint, which contains a spanning tree, such that the sum of shortest paths between every pair of nodes is as small as possible.

Applications

[edit]Minimum spanning trees have direct applications in the design of networks, including computer networks, telecommunications networks, transportation networks, water supply networks, and electrical grids (which they were first invented for, as mentioned above).[31] They are invoked as subroutines in algorithms for other problems, including the Christofides algorithm for approximating the traveling salesman problem,[32] approximating the multi-terminal minimum cut problem (which is equivalent in the single-terminal case to the maximum flow problem),[33] and approximating the minimum-cost weighted perfect matching.[34]

Other practical applications based on minimal spanning trees include:

- Taxonomy.[35]

- Cluster analysis: clustering points in the plane,[36] single-linkage clustering (a method of hierarchical clustering),[37] graph-theoretic clustering,[38] and clustering gene expression data.[39]

- Constructing trees for broadcasting in computer networks.[40]

- Image registration[41] and segmentation[42] – see minimum spanning tree-based segmentation.

- Curvilinear feature extraction in computer vision.[43]

- Handwriting recognition of mathematical expressions.[44]

- Circuit design: implementing efficient multiple constant multiplications, as used in finite impulse response filters.[45]

- Regionalisation of socio-geographic areas, the grouping of areas into homogeneous, contiguous regions.[46]

- Comparing ecotoxicology data.[47]

- Topological observability in power systems.[48]

- Measuring homogeneity of two-dimensional materials.[49]

- Minimax process control.[50]

- Minimum spanning trees can also be used to describe financial markets.[51][52] A correlation matrix can be created by calculating a coefficient of correlation between any two stocks. This matrix can be represented topologically as a complex network and a minimum spanning tree can be constructed to visualize relationships.

References

[edit]- ^ "scipy.sparse.csgraph.minimum_spanning_tree - SciPy v1.7.1 Manual". Numpy and Scipy Documentation — Numpy and Scipy documentation. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

A minimum spanning tree is a graph consisting of the subset of edges which together connect all connected nodes, while minimizing the total sum of weights on the edges.

- ^ "networkx.algorithms.tree.mst.minimum_spanning_edges". NetworkX 2.6.2 documentation. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

A minimum spanning tree is a subgraph of the graph (a tree) with the minimum sum of edge weights. A spanning forest is a union of the spanning trees for each connected component of the graph.

- ^ "Do the minimum spanning trees of a weighted graph have the same number of edges with a given weight?". cs.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Pettie, Seth; Ramachandran, Vijaya (2002), "An optimal minimum spanning tree algorithm" (PDF), Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, 49 (1): 16–34, doi:10.1145/505241.505243, MR 2148431, S2CID 5362916.

- ^ Karger, David R.; Klein, Philip N.; Tarjan, Robert E. (1995), "A randomized linear-time algorithm to find minimum spanning trees", Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, 42 (2): 321–328, doi:10.1145/201019.201022, MR 1409738, S2CID 832583

- ^ Pettie, Seth; Ramachandran, Vijaya (2002), "Minimizing randomness in minimum spanning tree, parallel connectivity, and set maxima algorithms", Proc. 13th ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA '02), San Francisco, California, pp. 713–722, ISBN 9780898715132

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ a b Chazelle, Bernard (2000), "A minimum spanning tree algorithm with inverse-Ackermann type complexity", Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, 47 (6): 1028–1047, doi:10.1145/355541.355562, MR 1866456, S2CID 6276962.

- ^ Chazelle, Bernard (2000), "The soft heap: an approximate priority queue with optimal error rate", Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, 47 (6): 1012–1027, doi:10.1145/355541.355554, MR 1866455, S2CID 12556140.

- ^ Fredman, M. L.; Tarjan, R. E. (1987). "Fibonacci heaps and their uses in improved network optimization algorithms". Journal of the ACM. 34 (3): 596. doi:10.1145/28869.28874. S2CID 7904683.

- ^ Gabow, H. N.; Galil, Z.; Spencer, T.; Tarjan, R. E. (1986). "Efficient algorithms for finding minimum spanning trees in undirected and directed graphs". Combinatorica. 6 (2): 109. doi:10.1007/bf02579168. S2CID 35618095.

- ^ Fredman, M. L.; Willard, D. E. (1994), "Trans-dichotomous algorithms for minimum spanning trees and shortest paths", Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 48 (3): 533–551, doi:10.1016/S0022-0000(05)80064-9, MR 1279413.

- ^ Matsui, Tomomi (1995-03-10). "The minimum spanning tree problem on a planar graph". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 58 (1): 91–94. doi:10.1016/0166-218X(94)00095-U. ISSN 0166-218X.

- ^ Cheriton, David; Tarjan, Robert Endre (December 1976). "Finding Minimum Spanning Trees". SIAM Journal on Computing. 5 (4): 724–742. doi:10.1137/0205051. ISSN 0097-5397.

- ^ Chong, Ka Wong; Han, Yijie; Lam, Tak Wah (2001), "Concurrent threads and optimal parallel minimum spanning trees algorithm", Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, 48 (2): 297–323, doi:10.1145/375827.375847, MR 1868718, S2CID 1778676.

- ^ Pettie, Seth; Ramachandran, Vijaya (2002), "A randomized time-work optimal parallel algorithm for finding a minimum spanning forest" (PDF), SIAM Journal on Computing, 31 (6): 1879–1895, doi:10.1137/S0097539700371065, MR 1954882.

- ^ Steele, J. Michael (2002), "Minimal spanning trees for graphs with random edge lengths", Mathematics and computer science, II (Versailles, 2002), Trends Math., Basel: Birkhäuser, pp. 223–245, MR 1940139

- ^ a b Grötschel, Martin; Lovász, László; Schrijver, Alexander (1993), Geometric algorithms and combinatorial optimization, Algorithms and Combinatorics, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78240-4, ISBN 978-3-642-78242-8, MR 1261419

- ^ Garey, Michael R.; Johnson, David S. (1979). Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. Series of Books in the Mathematical Sciences (1st ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 9780716710455. MR 0519066. OCLC 247570676.. ND12

- ^ Gabow, Harold N. (1977), "Two algorithms for generating weighted spanning trees in order", SIAM Journal on Computing, 6 (1): 139–150, doi:10.1137/0206011, MR 0441784.

- ^ Eppstein, David (1992), "Finding the k smallest spanning trees", BIT, 32 (2): 237–248, doi:10.1007/BF01994879, MR 1172188, S2CID 121160520.

- ^ Frederickson, Greg N. (1997), "Ambivalent data structures for dynamic 2-edge-connectivity and k smallest spanning trees", SIAM Journal on Computing, 26 (2): 484–538, doi:10.1137/S0097539792226825, MR 1438526.

- ^ Jothi, Raja; Raghavachari, Balaji (2005), "Approximation Algorithms for the Capacitated Minimum Spanning Tree Problem and Its Variants in Network Design", ACM Trans. Algorithms, 1 (2): 265–282, doi:10.1145/1103963.1103967, S2CID 8302085

- ^ Hu, T. C. (1961), "The maximum capacity route problem", Operations Research, 9 (6): 898–900, doi:10.1287/opre.9.6.898, JSTOR 167055.

- ^ McDonald, Ryan; Pereira, Fernando; Ribarov, Kiril; Hajič, Jan (2005). "Non-projective dependency parsing using spanning tree algorithms" (PDF). Proc. HLT/EMNLP.

- ^ Spira, P. M.; Pan, A. (1975), "On finding and updating spanning trees and shortest paths" (PDF), SIAM Journal on Computing, 4 (3): 375–380, doi:10.1137/0204032, MR 0378466.

- ^ Holm, Jacob; de Lichtenberg, Kristian; Thorup, Mikkel (2001), "Poly-logarithmic deterministic fully dynamic algorithms for connectivity, minimum spanning tree, 2-edge, and biconnectivity", Journal of the Association for Computing Machinery, 48 (4): 723–760, doi:10.1145/502090.502095, MR 2144928, S2CID 7273552.

- ^ Chin, F.; Houck, D. (1978), "Algorithms for updating minimal spanning trees", Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 16 (3): 333–344, doi:10.1016/0022-0000(78)90022-3.

- ^ Chang, R.S.; Leu, S.J. (1997), "The minimum labeling spanning trees", Information Processing Letters, 63 (5): 277–282, doi:10.1016/s0020-0190(97)00127-0.

- ^ "Everything about Bottleneck Spanning Tree". flashing-thoughts.blogspot.ru. 5 June 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-12. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Graham, R. L.; Hell, Pavol (1985), "On the history of the minimum spanning tree problem", Annals of the History of Computing, 7 (1): 43–57, Bibcode:1985IAHC....7a..43G, doi:10.1109/MAHC.1985.10011, MR 0783327, S2CID 10555375

- ^ Nicos Christofides, Worst-case analysis of a new heuristic for the travelling salesman problem, Report 388, Graduate School of Industrial Administration, CMU, 1976.

- ^ Dahlhaus, E.; Johnson, D. S.; Papadimitriou, C. H.; Seymour, P. D.; Yannakakis, M. (August 1994). "The complexity of multiterminal cuts" (PDF). SIAM Journal on Computing. 23 (4): 864–894. doi:10.1137/S0097539792225297. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2004. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Supowit, Kenneth J.; Plaisted, David A.; Reingold, Edward M. (1980). Heuristics for weighted perfect matching. 12th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC '80). New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 398–419. doi:10.1145/800141.804689.

- ^ Sneath, P. H. A. (1 August 1957). "The Application of Computers to Taxonomy". Journal of General Microbiology. 17 (1): 201–226. doi:10.1099/00221287-17-1-201. PMID 13475686.

- ^ Asano, T.; Bhattacharya, B.; Keil, M.; Yao, F. (1988). Clustering algorithms based on minimum and maximum spanning trees. Fourth Annual Symposium on Computational Geometry (SCG '88). Vol. 1. pp. 252–257. doi:10.1145/73393.73419.

- ^ Gower, J. C.; Ross, G. J. S. (1969). "Minimum Spanning Trees and Single Linkage Cluster Analysis". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. C (Applied Statistics). 18 (1): 54–64. doi:10.2307/2346439. JSTOR 2346439.

- ^ Päivinen, Niina (1 May 2005). "Clustering with a minimum spanning tree of scale-free-like structure". Pattern Recognition Letters. 26 (7): 921–930. Bibcode:2005PaReL..26..921P. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2004.09.039.

- ^ Xu, Y.; Olman, V.; Xu, D. (1 April 2002). "Clustering gene expression data using a graph-theoretic approach: an application of minimum spanning trees". Bioinformatics. 18 (4): 536–545. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.536. PMID 12016051.

- ^ Dalal, Yogen K.; Metcalfe, Robert M. (1 December 1978). "Reverse path forwarding of broadcast packets". Communications of the ACM. 21 (12): 1040–1048. doi:10.1145/359657.359665. S2CID 5638057.

- ^ Ma, B.; Hero, A.; Gorman, J.; Michel, O. (2000). Image registration with minimum spanning tree algorithm (PDF). International Conference on Image Processing. Vol. 1. pp. 481–484. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2000.901000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ P. Felzenszwalb, D. Huttenlocher: Efficient Graph-Based Image Segmentation. IJCV 59(2) (September 2004)

- ^ Suk, Minsoo; Song, Ohyoung (1 June 1984). "Curvilinear feature extraction using minimum spanning trees". Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing. 26 (3): 400–411. doi:10.1016/0734-189X(84)90221-4.

- ^ Tapia, Ernesto; Rojas, Raúl (2004). "Recognition of On-line Handwritten Mathematical Expressions Using a Minimum Spanning Tree Construction and Symbol Dominance" (PDF). Graphics Recognition. Recent Advances and Perspectives. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3088. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 329–340. ISBN 978-3540224785. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Ohlsson, H. (2004). Implementation of low complexity FIR filters using a minimum spanning tree. 12th IEEE Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON 2004). Vol. 1. pp. 261–264. doi:10.1109/MELCON.2004.1346826.

- ^ Assunção, R. M.; M. C. Neves; G. Câmara; C. Da Costa Freitas (2006). "Efficient regionalization techniques for socio-economic geographical units using minimum spanning trees". International Journal of Geographical Information Science. 20 (7): 797–811. Bibcode:2006IJGIS..20..797A. doi:10.1080/13658810600665111. S2CID 2530748.

- ^ Devillers, J.; Dore, J.C. (1 April 1989). "Heuristic potency of the minimum spanning tree (MST) method in toxicology". Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 17 (2): 227–235. Bibcode:1989EcoES..17..227D. doi:10.1016/0147-6513(89)90042-0. PMID 2737116.

- ^ Mori, H.; Tsuzuki, S. (1 May 1991). "A fast method for topological observability analysis using a minimum spanning tree technique". IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 6 (2): 491–500. Bibcode:1991ITPSy...6..491M. doi:10.1109/59.76691.

- ^ Filliben, James J.; Kafadar, Karen; Shier, Douglas R. (1 January 1983). "Testing for homogeneity of two-dimensional surfaces". Mathematical Modelling. 4 (2): 167–189. doi:10.1016/0270-0255(83)90026-X.

- ^ Kalaba, Robert E. (1963), Graph Theory and Automatic Control (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2016

- ^ Mantegna, R. N. (1999). Hierarchical structure in financial markets. The European Physical Journal B-Condensed Matter and Complex Systems, 11(1), 193–197.

- ^ Djauhari, M., & Gan, S. (2015). Optimality problem of network topology in stocks market analysis. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 419, 108–114.

Further reading

[edit]- Otakar Boruvka on Minimum Spanning Tree Problem (translation of both 1926 papers, comments, history) (2000) Jaroslav Nešetřil, Eva Milková, Helena Nesetrilová. (Section 7 gives his algorithm, which looks like a cross between Prim's and Kruskal's.)

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Chapter 23: Minimum Spanning Trees, pp. 561–579.

- Eisner, Jason (1997). State-of-the-art algorithms for minimum spanning trees: A tutorial discussion. Manuscript, University of Pennsylvania, April. 78 pp.

- Kromkowski, John David. "Still Unmelted after All These Years", in Annual Editions, Race and Ethnic Relations, 17/e (2009 McGraw Hill) (Using minimum spanning tree as method of demographic analysis of ethnic diversity across the United States).

External links

[edit]Minimum spanning tree

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Background

Formal Definition

In graph theory, a spanning tree of a connected undirected graph is a subgraph that includes all vertices in and is both connected and acyclic, necessarily containing exactly edges.[6] A minimum spanning tree (MST) of a connected, undirected, edge-weighted graph with edge weights for each edge is a spanning tree whose total weight is minimized among all possible spanning trees of .[1][4] To illustrate, consider a simple connected undirected graph with four vertices and five weighted edges: with weight 1, with weight 2, with weight 3, with weight 4, and with weight 1. One possible MST consists of the edges (weight 1), (weight 2), and (weight 1); this subgraph connects all four vertices without cycles and has a total weight of 4, which is minimal.Graph Theory Prerequisites

In graph theory, an undirected graph is formally defined as a pair , where is a finite set of vertices (also called nodes) and is a set of edges, each edge being an unordered pair of distinct vertices from .[7] This structure models symmetric relationships, such as mutual connections between entities, without implying direction. Connectivity in an undirected graph refers to the existence of a path—a sequence of adjacent edges—between any pair of vertices; a graph is connected if such paths exist for every pair.[8] Many applications of undirected graphs involve weights assigned to edges to represent costs, distances, or capacities, forming a weighted undirected graph where each edge has a weight .[9] Weights are often non-negative in contexts like network design. If a graph is not connected, it decomposes into two or more connected components, each being a maximal connected subgraph; isolated vertices form singleton components.[10] For a minimum spanning tree to exist and span all vertices, the graph must be connected, as disconnected components cannot be linked without additional edges.[8] A tree is a connected undirected graph that contains no cycles and thus has exactly edges, where denotes the number of vertices.[11] This minimal connectivity ensures a unique path between any pair of vertices. A spanning tree of a connected undirected graph is a subgraph that is a tree and includes every vertex in , effectively providing a skeletal structure of without redundancy.[12] A cycle in an undirected graph is a closed path where the starting and ending vertices are the same, and no other vertices repeat, forming a loop of at least three edges.[13] Cycles introduce redundancy in connectivity, distinguishing them from trees. A cut, or edge cut, arises from a partition of the vertex set into two nonempty subsets and ; the edges with one endpoint in and the other in form the cutset, representing the connections across the partition.[14] These concepts underpin the structure of spanning trees, where avoiding cycles while crossing necessary cuts ensures full connectivity.Fundamental Properties

Existence, Uniqueness, and Multiplicity

In any connected, undirected graph with real-valued edge weights (typically assumed non-negative), a minimum spanning tree (MST) exists. This follows from the non-emptiness of the set of spanning trees in a connected graph and the finiteness of this set, ensuring that the total edge weights achieve a minimum value among them.[15] One constructive proof proceeds inductively: begin with a single vertex as a trivial MST, then repeatedly add the minimum-weight edge connecting a new vertex to the current tree without forming a cycle, leveraging the cut property to guarantee optimality at each step.[16] This greedy approach aligns with the existence guaranteed by the optimization over the compact set of spanning trees.[17] The uniqueness of an MST depends on the edge weights. If all edge weights in the graph are distinct, then there is exactly one MST.[15] To see this, suppose there are two distinct MSTs and . Consider an edge of minimum weight in the symmetric difference , and without loss of generality assume but . The unique path in between the endpoints of must contain some edge with weight strictly greater than that of (due to distinct weights). Replacing with in yields a spanning tree with lower total weight, contradicting the minimality of . Thus, no such distinct MSTs can exist.[17] When edge weights are not all distinct, multiple MSTs may exist, all sharing the same minimum total weight but differing in their edge sets. For instance, consider a cycle graph on four vertices with all edges of equal weight 1; the MSTs are any three edges forming a path (e.g., --- or ---), each with total weight 3, while including all four edges would create a cycle.[1] In general, multiplicity arises when there are ties in weights that allow alternative edge selections without increasing the total cost, as seen in graphs with symmetric structures or equal-weight parallel options.[15]Cycle Property

The cycle property of minimum spanning trees states that, for any cycle in an undirected connected weighted graph , the edge with the maximum weight in cannot belong to any minimum spanning tree (MST) of .[18] This property holds under the simplifying assumption that all edge weights in are distinct, which ensures uniqueness in comparisons without loss of generality for the general case.[18] To prove this, assume for contradiction that some MST of contains the maximum-weight edge from cycle . Removing from disconnects the graph into two components, defining a cut where is one component and is the other. Since crosses this cut and also lies on cycle , there must exist another edge in that also crosses the cut (as connects vertices on both sides). The spanning tree connects all vertices and has no cycles, so is also a spanning tree. Moreover, since has strictly lower weight than (by the choice of ), the total weight of is less than that of , contradicting the minimality of . Thus, no MST can include .[18] A direct corollary of the cycle property is that every MST of is acyclic, reinforcing its tree structure: if an MST contained a cycle, its maximum-weight edge would violate the property, leading to a contradiction.[18] For illustration, consider a simple cycle graph with three vertices , , and , and edges with weight 1, with weight 2, and with weight 3. The unique MST is the tree with total weight 3. The spanning tree has total weight 4, which is not minimum. CA cannot be part of any MST, as it is the heaviest edge in the cycle, and its inclusion would allow replacement by the lighter to reduce the total weight without disconnecting the graph.[19]Cut Property

The cut property states that, in a connected undirected graph with nonnegative edge weights , for any partition of the vertex set into two nonempty disjoint subsets and , if is a minimum-weight edge with one endpoint in and the other in , then belongs to some minimum spanning tree of .[20] If all edge weights in are distinct, then belongs to every minimum spanning tree of .[21] To prove the cut property, consider an arbitrary minimum spanning tree of . If already contains , the property holds. Otherwise, add to , forming a cycle . Since crosses the cut , must contain at least one other edge that also crosses the cut (as cycles cross cuts an even number of times). The edge has weight , so the graph is a spanning tree with total weight at most that of . Thus, is also a minimum spanning tree containing . If weights are distinct, then , so any MST excluding can be improved by this exchange, implying is in every MST.[21][1] This property holds even if multiple edges share the minimum crossing weight; any such edge can be included in some MST without increasing the total weight.[22] For example, consider a graph with vertices and edges (weight 1), (weight 2), (weight 3), (weight 4), (weight 5), (weight 6). For the cut and , the crossing edges are (3), (5), (6), (4); the minimum-weight crossing edge is (3). One MST is with total weight 6, which includes .Proof Techniques and Equivalences

Contraction

In graph theory, the contraction of an edge in an undirected, edge-weighted graph merges the vertices and into a single supernode, denoted as , such that all edges originally incident to or (except itself) become incident to ; any resulting self-loops are removed, and for any pair of supernodes with multiple parallel edges, only the minimum-weight edge is retained.[15] This operation reduces the number of vertices by one while preserving the connectivity and relative weights of the remaining edges.[24] Contracting an edge that belongs to some minimum spanning tree (MST) of maintains key structural properties of the MST in the resulting contracted graph , ensuring that the minimum spanning forest of corresponds to a partial MST of .[15] Specifically, if is a forest consisting of edges from an MST of , contracting the edges in yields a graph where the supernodes represent the connected components induced by , and the MST of this contracted graph can be expanded to complete an MST of the original graph.[25] In algorithmic contexts, contraction serves as a reduction technique for constructing MSTs by iteratively identifying and contracting "safe" edges—those that appear in some MST—thereby simplifying the graph while building the MST incrementally from the contracted edges.[15] This process ensures that the final MST is formed by the union of all contracted edges, as each contraction step preserves the optimality invariant.[26] A fundamental theorem underpinning this approach states that if is a forest in and is obtained by contracting all edges in , then combining with any MST of (expanded by restoring the supernodes in ) yields an MST of .[25] This equivalence holds because contraction does not introduce new cycles or alter the minimum weights across cuts in a way that violates MST optimality.[15]Minimum-Cost Edge and Subgraph

A minimum spanning tree (MST) of a connected, edge-weighted undirected graph with nonnegative edge weights is not only the minimum-weight spanning tree but also the minimum-weight connected spanning subgraph of . That is, among all subgraphs of that connect every pair of vertices in , the total edge weight of an MST is the smallest possible. This property underscores that adding extra edges to an MST can only increase or maintain the total cost, but never decrease it below that of the MST. To see why, consider any connected spanning subgraph of . If is acyclic (i.e., a tree), then by the definition of an MST, the weight of is at least that of the MST . If contains cycles, repeatedly apply the cycle property: in any cycle of , remove the maximum-weight edge, which disconnects no component since the remaining path connects the endpoints. Each such removal yields a connected spanning subgraph of equal or strictly lower weight (if the removed edge had positive weight). Continuing until becomes acyclic produces a spanning tree whose weight is at most that of the original . Since is an MST, its weight is no greater than that of this derived tree, and thus no greater than that of . A key corollary is that the minimum-weight edge in belongs to some MST of . This follows as a special case of the cut property: let be the minimum-weight edge in , and consider the cut . Then is the minimum-weight edge crossing this cut (as it is the global minimum), so lies on some MST. This characterization implies that solving for an MST yields the optimal solution not just among trees but over the broader class of all connected spanning subgraphs, justifying the focus on tree structures in algorithms for this problem.Decision Tree Characterization

In the comparison-based model for solving the minimum spanning tree (MST) problem, the decision tree represents an algorithm's query process as a binary tree structure. Each internal node corresponds to a comparison between the weights of two specific edges in the graph, with the two branches representing the outcomes: one where the weight of the first edge is less than the second, and the other where it is greater (assuming distinct weights for simplicity). The leaves of the tree each specify a particular set of edges that form the MST, consistent with the sequence of comparison outcomes leading to that leaf. This model captures the information gained solely through weight comparisons, without assuming access to the actual numerical values.[27] The structure of this decision tree provides a characterization of the MST problem's query complexity. The height of the tree denotes the worst-case number of comparisons required to identify the MST. A key insight is that the number of leaves must be at least as large as the number of distinct possible MSTs in the graph, since each possible MST must be output for some assignment of edge weights consistent with the comparisons. Consequently, the height is bounded below by the base-2 logarithm of the number of possible MSTs, offering an information-theoretic lower bound on the comparisons needed. When the MST is unique for generic weight assignments, the decision tree has fewer paths, simplifying the query process.[27] This characterization is leveraged to establish lower bounds on comparison-based MST algorithms. For instance, the number of possible MSTs implies that distinguishing among them requires sufficient comparisons, but tighter bounds arise from adversarial arguments. In particular, consider a cycle graph with |E| edges; the MST excludes the unique heaviest edge, and identifying it demands Ω(|E|) comparisons in the worst case, as this reduces to finding the maximum among |E| unordered elements. Thus, any comparison-based MST algorithm requires Ω(|E|) comparisons in the worst case for general graphs.[27] Chazelle formalized this by proving that the decision-tree complexity of the MST problem is Θ(|E| α(|E|, n)), where α is the inverse Ackermann function, and demonstrated an algorithm achieving this bound, thereby fully characterizing the problem's complexity in the comparison model.[28]Classic Algorithms

Kruskal's Algorithm

Kruskal's algorithm is a greedy method for computing a minimum spanning tree (MST) in a connected, undirected graph with non-negative edge weights. Introduced by Joseph B. Kruskal in 1956, it constructs the MST by progressively adding the lightest edges that do not form cycles.[29] The algorithm begins by sorting all edges in non-decreasing order of weight. It maintains a forest of trees, initially consisting of |V| singleton trees, one for each vertex. Using a disjoint-set (Union-Find) data structure to track connected components, it iterates through the sorted edges: for each edge (u, v) with weight w, if u and v belong to different components, the edge is added to the forest and the components are merged via union operation. This process continues until the forest contains a single tree spanning all vertices. Cycle detection via the find operation ensures no redundant edges are included.[30] Here is the pseudocode for Kruskal's algorithm:function Kruskal(G = (V, E), w):

MST = empty set

for each vertex v in V:

make-set(v) // Initialize Union-Find

sort E by increasing w(e)

for each edge e = (u, v) in sorted E:

if find(u) ≠ find(v):

MST = MST ∪ {e}

union(u, v)

return MST

function Kruskal(G = (V, E), w):

MST = empty set

for each vertex v in V:

make-set(v) // Initialize Union-Find

sort E by increasing w(e)

for each edge e = (u, v) in sorted E:

if find(u) ≠ find(v):

MST = MST ∪ {e}

union(u, v)

return MST

- Start with components {A}, {B}, {C}, {D}.

- Add BC (1): merges to {A}, {B,C}, {D}; MST weight = 1.

- Add AB (2): B and A differ, merges to {A,B,C}, {D}; MST weight = 3.

- Skip AC (3): A and C same component.

- Add BD (4): B and D differ, merges to {A,B,C,D}; MST weight = 7.

- Skip remaining edges: all vertices connected.

Prim's Algorithm

Prim's algorithm is a greedy method for constructing a minimum spanning tree (MST) in a connected, undirected graph with weighted edges. Developed by Robert C. Prim, the algorithm begins with an arbitrary starting vertex and iteratively grows a tree by adding the minimum-weight edge that connects a vertex in the current tree to a vertex outside it.[32] This process continues until all vertices are included, ensuring the result is an MST.[33] The algorithm maintains a priority queue to track the minimum key (edge weight) for each vertex not yet in the tree, along with the parent vertex that provides this key. It starts by setting the key of the starting vertex to 0 and all others to infinity, then repeatedly extracts the vertex with the minimum key, adds it to the tree, and relaxes (updates) the keys of its adjacent vertices if a cheaper connection is found. Pseudocode for Prim's algorithm using a generic priority queue is as follows:PRIM(G, w, r)

for each vertex u in G.V

key[u] ← ∞

parent[u] ← NIL

key[r] ← 0

create a priority queue Q containing all vertices in G.V

while Q is not empty

u ← EXTRACT-MIN(Q)

for each vertex v adjacent to u

if w(u, v) < key[v]

key[v] ← w(u, v)

parent[v] ← u

DECREASE-KEY(Q, v, key[v])

return the tree defined by the parent array

PRIM(G, w, r)

for each vertex u in G.V

key[u] ← ∞

parent[u] ← NIL

key[r] ← 0

create a priority queue Q containing all vertices in G.V

while Q is not empty

u ← EXTRACT-MIN(Q)

for each vertex v adjacent to u

if w(u, v) < key[v]

key[v] ← w(u, v)

parent[v] ← u

DECREASE-KEY(Q, v, key[v])

return the tree defined by the parent array

Borůvka's Algorithm

Borůvka's algorithm, introduced in 1926 by Czech mathematician Otakar Borůvka, provides an early solution to the minimum spanning tree problem, motivated by the design of efficient electrical networks for Moravia.[3] This approach predates the more widely known Kruskal's and Prim's algorithms by several decades and represents a foundational contribution to combinatorial optimization.[3] The algorithm operates in phases on a connected, undirected graph with weighted edges, starting with each vertex as its own connected component. In each phase, for every current component, the minimum-weight edge that connects it to any vertex outside the component is identified and selected.[35] These selections occur simultaneously across all components, with each component choosing its cheapest outgoing edge independently; if an edge is the minimum outgoing for multiple components (such as both endpoints), it is still included only once. The selected edges are added to the spanning forest, connecting multiple components into larger ones. The newly connected components are then merged into single supervertices via contraction, and parallel edges between supervertices are handled appropriately (e.g., keeping the minimum weight if needed), with intra-super vertex edges discarded.[35] The process repeats over multiple phases until only one component remains, yielding the minimum spanning tree. In cases of multiplicity, where multiple edges have the same minimum weight outgoing from a component, the algorithm selects an arbitrary one to ensure progress without affecting optimality.[36] The correctness of Borůvka's algorithm follows from the cut property of minimum spanning trees: each selected edge is the lightest edge crossing the cut defined by its originating component and the rest of the graph, ensuring it belongs to some minimum spanning tree, and the contractions preserve the minimum spanning tree structure for the reduced graph.[36] With respect to time complexity, the algorithm requires at most phases, as each phase reduces the number of components by at least half, and each phase can be implemented in time by scanning all edges to find the minimum outgoing edges for components. Thus, the overall running time is .[37]Advanced Algorithms

Deterministic Improvements

The development of deterministic algorithms for computing minimum spanning trees (MSTs) has evolved significantly since the introduction of the classic methods in the mid-20th century, with key refinements emerging in the late 20th and early 21st centuries to achieve near-linear worst-case running times. Early algorithms, such as Kruskal's from 1956 and Prim's from 1957, achieved O(|E| log |E|) time using union-find structures and priority queues, but subsequent work focused on reducing the logarithmic factors through advanced data structures and filtering techniques. By the 1980s, researchers introduced sophisticated heap variants and decomposition methods to push complexities closer to linear, culminating in algorithms that incorporate the slowly growing inverse Ackermann function in the 2000s.[38][39] Improvements to Kruskal's and Prim's algorithms often employ filtering techniques to eliminate edges unlikely to be in the MST without full sorting or exhaustive priority queue operations, thereby reducing the number of edges considered in subsequent steps. In Kruskal's context, filtering identifies and discards edges that violate the cycle property—those forming cycles with lower-weight edges already processed—allowing partial sorting or bucketing of the remaining candidate edges. For Prim's algorithm, similar filtering integrates with priority queues to prune high-weight incident edges early, leveraging cut properties to bound the search space. These techniques, while initially practical, have been formalized in theoretical frameworks to guarantee worst-case efficiency gains, often halving the effective edge set size in dense graphs.[40] A landmark deterministic improvement is the algorithm by Gabow, Galil, Spencer, and Tarjan from 1986, which computes an MST in O(|E| log |V| / log log |V|) time for a graph with |V| vertices and |E| edges. This method combines Borůvka-style phase contractions with specialized Fibonacci-like heaps (F-heaps) that support efficient decrease-key and extract-min operations, enabling faster merging of components during union steps. The algorithm processes edges in logarithmic phases, using the heaps to select minimum crossing edges across cuts, and achieves its bound through amortized analysis of heap operations that minimize logarithmic overhead. This represents a substantial refinement over earlier O(|E| log |V|) implementations, particularly for sparse graphs where the denominator term provides asymptotic speedup.[39][41] The most advanced deterministic MST algorithm, developed by Chazelle in 2000, runs in O(|E| \alpha(|V|)) time, where \alpha is the inverse Ackermann function, which grows slower than any iterated logarithm and is effectively constant for all practical graph sizes. This algorithm iterates Borůvka phases but uses soft heaps—an approximate priority queue allowing controlled errors in key values—to filter and contract components efficiently, ensuring errors do not propagate to the final MST. It builds on Borůvka phases with multilevel edge filtering, using soft heaps to manage approximate priorities during component contractions. The soft heap's error rate of O(1/n) per extraction guarantees exact MST recovery after a linear number of phases, marking the tightest known worst-case bound for comparison-based models without randomization.[38][42] These refinements highlight a progression from brute-force greedy selections in the 1950s to structure-aware optimizations by the 2000s, with each advance building on cut and cycle properties while minimizing data structure overhead. The inverse-Ackermann complexity of Chazelle's method is widely regarded as optimal up to constants in the decision-tree model, influencing subsequent work on dynamic and parallel MST variants.[43][44]Randomized and Near-Linear Time Algorithms

The Karger-Klein-Tarjan algorithm provides a randomized method for computing a minimum spanning tree in an undirected, connected graph with nonnegative edge weights, achieving an expected running time of O(m), where m is the number of edges.[45] This Las Vegas algorithm, which always produces the correct MST but with randomized runtime, combines random edge sampling with a linear-time verification procedure to efficiently sparsify the graph while preserving the MST structure.[45] Building on the contraction phases of Borůvka's algorithm, the approach iteratively identifies and contracts minimum-weight edges incident to each component, but incorporates randomization to address the issue of dense subgraphs slowing down progress. In each phase, a subset of edges is randomly sampled such that each edge is included independently with probability p = 1/2, ensuring, via the sampling lemma, that the MSF of the sampled graph allows safe filtering of heavy edges, preserving the original MST while bounding the number of candidate edges.[45] Following sampling, a verification step discards edges that cannot belong to any MST by checking against the cut property, reducing the edge count to O(n) in expectation per phase, where n is the number of vertices.[45] Contractions then merge components, repeating until a single tree remains. The expected time analysis hinges on probabilistic guarantees for component reduction: with high probability (at least 1 - 1/n^c for constant c), each phase contracts a constant fraction of the vertices, leading to O(log n) phases overall.[45] A key sampling lemma proves that the probability of failing to contract a particular vertex is exponentially small, bounding the expected number of surviving edges and ensuring the total time is linear despite occasional denser phases.[46] This backward analysis technique simplifies proving the preservation of MST edges under sampling.[46] In practice, the algorithm's expected linear time makes it particularly efficient for large, sparse graphs, often outperforming deterministic methods like improved versions of Kruskal's or Prim's in empirical studies due to reduced constant factors in edge processing.[47]Parallel and Distributed Algorithms

Parallel algorithms for minimum spanning trees leverage the inherent parallelism in methods like Borůvka's algorithm, where each phase involves independently selecting minimum-weight outgoing edges from graph components. In the parallel Borůvka approach, these phases are executed concurrently across components in the PRAM model, with each iteration reducing the number of components by a constant factor, leading to O(log |V|) rounds until a single component remains. Graph contraction techniques, such as tree or star contraction, are used to merge components efficiently while updating cross edges, ensuring the selected edges form part of the MST.[48] This parallelization achieves work-efficient performance, matching the sequential bound of O(|E| log |V|) total operations, with span (parallel time) of O(log² |V|) or O(log³ |V|) depending on the contraction method. Modern implementations, such as filter-enhanced variants, further optimize for distributed-memory systems by combining Borůvka phases with edge filtering, yielding expected work O(|E| + |V| log |V| log(|E|/|V|)) and polylogarithmic span, enabling scalability on thousands of cores.[48][49] In distributed settings, the Gallager-Humblet-Spira (GHS) algorithm provides a foundational message-passing protocol for constructing MSTs in asynchronous networks. Nodes initiate fragments and iteratively merge them by exchanging messages to identify and select minimum-weight outgoing edges, progressing through levels up to O(log |V|) to form the spanning tree. The algorithm uses specific message types (e.g., Connect, Accept, Reject) for coordination, incurring O(|E| + |V| log |V|) total messages and O(|V| log |V|) time in the worst case, though synchronous variants achieve O(log |V|) rounds.[50] These parallel and distributed MST algorithms find applications in large-scale networks, such as wireless sensor and peer-to-peer systems, where they facilitate energy-efficient data aggregation and routing by minimizing total edge costs. In sensor networks, distributed MSTs reduce communication overhead for broadcasting and fusion tasks, with approximations like neighbor-neighbor-tree methods achieving O(|V|) expected messages compared to GHS's higher complexity, thus conserving battery life in resource-constrained environments.[51]Special Cases and Complexity

Dense Graphs

In dense graphs, where the number of edges is on the order of with denoting the number of vertices, minimum spanning tree (MST) algorithms exploit the graph's structure to achieve running times linear in the input size. The input representation, such as an adjacency matrix, requires space and time to process, making algorithms asymptotically optimal for this regime.[1] A straightforward approach adapts Prim's algorithm using a dense representation like an adjacency matrix, where the priority queue is simulated by linearly scanning the rows to select the minimum-weight edge connecting the growing tree to an unvisited vertex. This implementation runs in time, independent of explicit heap structures, as each of the iterations examines up to potential edges.[1] For example, in a complete graph, scanning the adjacency matrix rows directly identifies the cheapest connection at each step, avoiding the overhead of sparse data structures.[1] The Fredman-Tarjan algorithm provides a deterministic solution using adapted Fibonacci heaps for priority queue operations, which reduces to in dense cases since .[52] This bound is linear relative to the input size, as processing all edges and vertices scales with the input complexity.[52]Integer Edge Weights

When edge weights are small non-negative integers, a variant of Kruskal's algorithm using bucket sort can compute the minimum spanning tree in linear time. The edges are distributed into buckets indexed by their weights, ranging from 0 to W, where W is the maximum edge weight. These buckets are then processed sequentially in increasing order of weight, adding an edge to the spanning tree if it connects distinct components in the union-find structure. This avoids the O(m log m) cost of general sorting, replacing it with O(m + W) time for bucketing and scanning, while union-find operations with path compression and union by rank take nearly linear time O(m α(m, n)), where α is the inverse Ackermann function. The overall running time is thus linear in m when W = O(m). This bucket sort approach is efficient when edge weights are small, such as W = O(m). For larger integer weights up to polynomial in |V|, linearity in sorting can be achieved via radix sort or advanced integer sorting techniques, maintaining the total time linear in the input size. For integer weights up to poly(|V|), a deterministic linear-time algorithm in the trans-dichotomous RAM model was developed by Fredman and Willard, leveraging fusion trees for priority queue operations in a Borůvka-style framework to simulate efficient edge selection without explicit sorting. The running time is O(|E| + |V|), assuming operations on words of size log |V| bits. This seminal result exploits the integer structure to perform integer comparisons and manipulations in constant time per word.[53]Optimal Deterministic Algorithms

The fastest known deterministic algorithm for computing a minimum spanning tree of a connected undirected graph with vertices and edges runs in time, where denotes the extremely slow-growing inverse Ackermann function.[54] This algorithm, developed by Bernard Chazelle, builds upon earlier techniques such as link-cut trees and soft heaps to achieve near-linear performance while remaining fully deterministic.[38] It processes the graph by iteratively contracting components and using a sophisticated data structure to select edges efficiently, ensuring the time bound holds across all graph densities.[54] A fundamental lower bound for the minimum spanning tree problem arises from its decision-tree complexity, which is in the comparison model.[28] This bound, established by showing that the problem's computational complexity matches its decision-tree depth, implies that any deterministic algorithm must examine edge weight comparisons in the worst case, equivalent to at least scanning the entire input.[43] Consequently, no deterministic solution can asymptotically outperform this threshold without additional assumptions on the input model. As of 2025, it remains an open question whether a deterministic -time algorithm exists for the general case, with Chazelle's result representing the closest known approach to this linear bound.[55] Although asymptotically superior to classical methods like Kruskal's or Prim's algorithms, which require time, Chazelle's implementation is highly intricate, involving advanced amortized analysis and specialized data structures that render it impractical for real-world use.[56]Variants

Minimum Spanning Trees with Random Weights

In the study of minimum spanning trees (MSTs) with random weights, the standard model considers the complete graph on vertices where each edge weight is an independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variable drawn from a continuous distribution, such as the uniform distribution on or the exponential distribution with rate 1 (mean 1). This setup captures the behavior of MSTs in dense networks where all possible connections exist, and weights represent random costs or distances. The i.i.d. assumption ensures that the relative ordering of edge weights is a uniform random permutation, which simplifies analysis via algorithms like Kruskal's, as the MST is formed by adding the lightest non-cycle-forming edges in sorted order.[57] The expected total weight of the MST in this model has been rigorously analyzed for distributions with positive density at 0. For both the uniform and exponential (rate 1) distributions, which have density at the origin, the expected cost converges asymptotically to as , where is Apéry's constant. This constant arises from the local analysis near weight 0, where the density determines the likelihood of small edges being selected, and the MST effectively samples from the lightest available cross-component edges without heavy tails dominating. More generally, for distributions with density differentiable from the left at 0 with and finite variance, the limit is . For certain other distributions, such as those leading to incremental merging costs in union-find structures under random ordering, exact expected costs can take the form , the -th harmonic number, which grows as (where is the Euler-Mascheroni constant); however, this form is specific to models like exponentially distributed increments in component merging rather than direct i.i.d. edge weights.[57] Key properties of the random-weight MST highlight its concentration around light edges. With high probability (approaching 1 as ), all edges in the MST have weights at most , ensuring no "heavy" edges (relative to the scale of the lightest possible connections) are included; this follows from the fact that the maximum edge weight in the MST is the weight at which the graph becomes connected in the random ordering, which occurs before the threshold for cycles in heavy edges. Moreover, under continuous distributions like uniform or exponential, the MST is unique with probability 1, as ties in edge weights have probability 0. These properties underscore the robustness of the MST to perturbations in dense random settings.[57] This random-weight model on complete graphs provides a foundational framework for understanding MSTs in more structured random environments, such as random geometric graphs where vertices are placed uniformly in a unit cube and edge weights are Euclidean distances. In the geometric case, the complete graph with i.i.d. weights approximates the behavior when points are in general position and distances are "random-like," though geometric MSTs exhibit different scaling (e.g., in dimensions); the i.i.d. model thus isolates probabilistic effects without spatial correlations, aiding theoretical bounds and simulations for network design in wireless or sensor applications.Fractional Minimum Spanning Tree

The fractional minimum spanning tree is defined as the optimal solution to the linear programming relaxation of the integer linear program for the minimum spanning tree problem. In this relaxation, the binary variables indicating whether an edge is included in the spanning tree are replaced by continuous variables . The constraints are designed to ensure that an integer solution corresponds to a spanning tree—providing connectivity across the graph and preventing cycles—but the acyclicity condition is inherently relaxed in the fractional setting, allowing solutions that may fractionally "cover" cycles. Connectivity is enforced either through cut-based constraints or equivalently via multicommodity flow constraints in polynomial-size formulations.[58] A standard exponential-size formulation of this LP uses cut constraints derived from the cut property of MSTs: Here, denotes the set of edges with one endpoint in and the other in .[59] This LP relaxation is exact for the MST problem: its optimal value equals the cost of a minimum spanning tree, and every basic optimal solution is integral, corresponding precisely to the characteristic vector of an MST. Consequently, the integrality gap is zero, as the polytope defined by the constraints—the spanning tree polytope—has integer vertices. This property follows from the total unimodularity of the constraint matrix or the matroid polytope structure.[60] For a polynomial-size alternative, connectivity can be modeled using multicommodity flows: introduce flow variables for paths and edges , requiring that unit demand can be routed between all vertex pairs (or from a fixed root to all others) subject to capacities on edges. The objective minimizes while satisfying flow conservation and demand constraints, with acyclicity relaxed through the minimization. This formulation yields an equivalent optimal value to the cut-based LP and supports the same integrality guarantee.[61] The fractional MST LP forms the foundation for approximation algorithms in harder variants, such as the minimum bounded-degree spanning tree, where randomized rounding or iterative methods applied to the fractional solution yield guarantees like -approximation. It also underpins matroid intersection algorithms, as a spanning tree is a maximum common independent set in the intersection of the graphic matroid (cycle-free subsets) and a uniform partition matroid (size at most ); the LP relaxation enables efficient separation oracles and rounding procedures in such frameworks.[62]Other Variants

The bottleneck minimum spanning tree (BMST), also known as the minimum maximin spanning tree, is a spanning tree that minimizes the weight of the heaviest edge in the tree. This variant prioritizes avoiding high-cost edges over total weight minimization, with applications in network reliability and resource allocation where the weakest link determines performance. A BMST can be computed in linear time using Camerini's algorithm, which iteratively contracts components and finds MSTs on reduced graphs, or equivalently via Kruskal's algorithm by sorting edges and adding until connectivity, with the final edge's weight as the bottleneck. Interestingly, any minimum spanning tree of the graph is also a BMST, as the property holds for undirected graphs under the bottleneck objective. For disconnected graphs, the minimum spanning forest (MSF) generalizes the MST by forming a collection of minimum spanning trees, one for each connected component, such that the total edge weight is minimized across all components. This structure preserves acyclicity and connects all vertices within their respective components, serving as a foundational tool in graph partitioning and clustering tasks on non-connected inputs. Standard MST algorithms like Prim's or Kruskal's naturally produce an MSF when applied to disconnected graphs, running in O(m log n) time where m and n are the number of edges and vertices.[63] Dynamic minimum spanning tree algorithms address the challenge of maintaining an MST under edge insertions and deletions, enabling efficient updates in evolving graphs such as communication networks or databases. Early approaches leverage link-cut trees, a data structure supporting link (add edge) and cut (remove edge) operations in O(log n) amortized time, which can represent the forest and facilitate MST recomputation by handling path queries and aggregations. For fully dynamic settings, the seminal Holm-de Lichtenberg-Thorup (HDT) algorithm achieves deterministic polylogarithmic update time of O(log² n) per operation by maintaining multiple levels of spanning forests and replacement edges, ensuring amortized efficiency across updates. Recent advancements have refined these to improved polylogarithmic update times, incorporating randomized techniques for denser graphs while preserving guarantees. In geometric settings, the Euclidean minimum spanning tree (EMST) connects a set of points in d-dimensional space using straight-line edges of minimal total length, forming the MST of the complete geometric graph. Unlike dense complete graphs, the EMST in 2D is a subgraph of the Delaunay triangulation—a planar graph with O(n) edges constructed in O(n log n) time—allowing efficient EMST computation by applying Kruskal's or Prim's algorithm solely on the triangulation's edges, achieving the same time bound. This approximation property extends to higher dimensions with O(n^{⌈d/2⌉}) edges in the Delaunay complex, though practical algorithms often use randomized incremental construction for speed. For sparse approximations, techniques like well-separated pair decomposition further reduce candidates to O(n) edges while providing constant-factor length guarantees.Applications

Network Design and Optimization

In the design of telecommunication backbone networks, minimum spanning trees (MSTs) are utilized to connect a set of nodes—such as regional hubs or data centers—with the minimum total edge cost, ensuring full connectivity without cycles. Edge weights typically represent installation costs, distances, or capacities for fiber optic links, allowing network operators to optimize infrastructure deployment for reliable, low-cost data transmission across large areas. For example, in planning a national telecom grid, an MST can select optimal routes among potential city connections, reducing overall capital expenditure while maintaining redundancy-free topology.[5] MSTs find direct application in cable laying and wiring problems, where the objective is to interconnect discrete points, such as buildings in a neighborhood or components on a circuit board, using the shortest total length of cable to avoid cycles and excess material. By modeling locations as vertices and possible cable paths as weighted edges (based on Euclidean distances or terrain factors), the MST yields a tree structure that minimizes wiring costs and simplifies installation logistics. This approach is widely adopted in electrical and utility engineering to balance connectivity with economic efficiency.[64] For scenarios requiring potential intermediate junctions, MSTs provide a foundational 2-approximation algorithm for the metric minimum Steiner tree problem, where additional Steiner points can be added to further shorten connections in communication or transportation networks. The method involves constructing a complete graph on the required terminals using shortest-path distances as edge weights, then computing the MST of this graph; its total weight is at most twice the optimal Steiner tree cost, as the optimal solution can be traversed in a tour of length less than twice its own, and the MST bounds that tour length. This approximation is particularly valuable in dense urban network planning, where exact Steiner solutions are computationally intensive.[65]Clustering and Data Analysis