Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chloride channel

View on Wikipedia| Voltage gated chloride channel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Voltage_CLC | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00654 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR014743 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1kpl / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| TCDB | 2.A.49 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 10 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1ots | ||||||||

| CDD | cd00400 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Chloride channels are a superfamily of poorly understood ion channels specific for chloride. These channels may conduct many different ions, but are named for chloride because its concentration in vivo is much higher than other anions.[1] Several families of voltage-gated channels and ligand-gated channels (e.g., the CaCC families) have been characterized in humans.

Voltage-gated chloride channels perform numerous crucial physiological and cellular functions, such as controlling pH, volume homeostasis, transporting organic solutes, regulating cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation. Based on sequence homology the chloride channels can be subdivided into a number of groups.

General functions

[edit]Voltage-gated chloride channels are important for setting cell resting membrane potential and maintaining proper cell volume. These channels conduct Cl− or other anions such as HCO−3, I−, SCN−, and NO−3. The structure of these channels are not like other known channels. The chloride channel subunits contain between 1 and 12 transmembrane segments. Some chloride channels are activated only by voltage (i.e., voltage-gated), while others are activated by Ca2+, other extracellular ligands, or pH.[2]

CLC family

[edit]The CLC family of chloride channels contains 10 or 12 transmembrane helices. Each protein forms a single pore. It has been shown that some members of this family form homodimers. In terms of primary structure, they are unrelated to known cation channels or other types of anion channels. Three CLC subfamilies are found in animals. CLCN1 is involved in setting and restoring the resting membrane potential of skeletal muscle, while other channels play important parts in solute concentration mechanisms in the kidney.[3] These proteins contain two CBS domains. Chloride channels are also important for maintaining safe ion concentrations within plant cells.[4]

Structure and mechanism

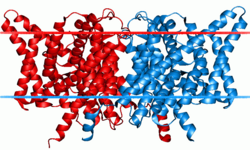

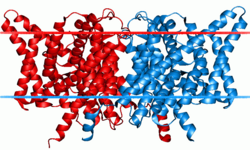

[edit]The CLC channel structure has not yet been resolved, however the structure of the CLC exchangers has been resolved by x-ray crystallography. Because the primary structure of the channels and exchangers are so similar, most assumptions about the structure of the channels are based on the structure established for the bacterial exchangers.[5]

Each channel or exchanger is composed of two similar subunits—a dimer—each subunit containing one pore. The proteins are formed from two copies of the same protein—a homodimer—though scientists have artificially combined subunits from different channels to form heterodimers. Each subunit binds ions independently of the other, meaning conduction or exchange occur independently in each subunit.[3]

Each subunit consists of two related halves oriented in opposite directions, forming an 'antiparallel' structure. These halves come together to form the anion pore.[5] The pore has a filter through which chloride and other anions can pass, but lets little else through. These water-filled pores filter anions via three binding sites—Sint, Scen, and Sext—which bind chloride and other anions. The names of these binding sites correspond to their positions within the membrane. Sint is exposed to intracellular fluid, Scen lies inside the membrane or in the center of the filter, and Sext is exposed to extracellular fluid.[4] Each binding site binds different chloride anions simultaneously. In the exchangers, these chloride ions do not interact strongly with one another, due to compensating interactions with the protein. In the channels, the protein does not shield chloride ions at one binding site from the neighboring negatively charged chlorides.[6] Each negative charge exerts a repulsive force on the negative charges next to it. Researchers have suggested that this mutual repulsion contributes to the high rate of conduction through the pore.[5]

CLC transporters shuttle H+ across the membrane. The H+ pathway in CLC transporters utilizes two glutamate residues—one on the extracellular side, Gluex, and one on the intracellular side, Gluin. Gluex also serves to regulate chloride exchange between the protein and extracellular solution. This means that the chloride and the proton share a common pathway on the extracellular side, but diverge on the intracellular side.[6]

CLC channels also have dependence on H+, but for gating rather than Cl− exchange. Instead of utilizing gradients to exchange two Cl− for one H+, the CLC channels transport one H+ while simultaneously transporting millions of anions.[6] This corresponds with one cycle of the slow gate.

Eukaryotic CLC channels also contain cytoplasmic domains. These domains have a pair of CBS motifs, whose function is not fully characterized yet.[5] Though the precise function of these domains is not fully characterized, their importance is illustrated by the pathologies resulting from their mutation. Thomsen's disease, Dent's disease, infantile malignant osteopetrosis, and Bartter's syndrome are all genetic disorders due to such mutations.

At least one role of the cytoplasmic CBS domains regards regulation via adenosine nucleotides. Particular CLC transporters and proteins have modulated activity when bound with ATP, ADP, AMP, or adenosine at the CBS domains. The specific effect is unique to each protein, but the implication is that certain CLC transporters and proteins are sensitive to the metabolic state of the cell.[6]

Selectivity

[edit]The Scen acts as the primary selectivity filter for most CLC proteins, allowing the following anions to pass through, from most selected to least: SCN−, Cl−, Br−, NO−

3, I−. Altering a serine residue at the selectivity filter, labeled Sercen, to a different amino acid alters the selectivity.[6]

Gating and kinetics

[edit]Gating occurs through two mechanisms: protopore or fast gating and common or slow gating. Common gating involves both protein subunits closing their pores at the same time (cooperation), while protopore gating involves independent opening and closing of each pore.[5] As the names imply, fast gating occur at a much faster rate than slow gating. Precise molecular mechanisms for gating are still being studied.

For the channels, when the slow gate is closed, no ions permeate through the pore. When the slow gate is open, the fast gates open spontaneously and independently of one another. Thus, the protein could have both gates open, or both gates closed, or just one of the two gates open. Single-channel patch-clamp studies demonstrated this biophysical property even before the dual-pore structure of CLC channels had been resolved. Each fast gate opens independently of the other and the ion conductance measured during these studies reflects a binomial distribution.[3]

H+ transport promotes opening of the common gate in CLC channels. For every opening and closing of the common gate, one H+ is transported across the membrane. The common gate is also affected by the bonding of adenosine nucleotides to the intracellular CBS domains. Inhibition or activation of the protein by these domains is specific to each protein.[6]

Function

[edit]The CLC channels allow chloride to flow down its electrochemical gradient, when open. These channels are expressed on the cell membrane. CLC channels contribute to the excitability of these membranes as well as transport ions across the membrane.[3]

The CLC exchangers are localized to intracellular components like endosomes or lysosomes and help regulate the pH of their compartments.[3]

Pathology

[edit]Bartter's syndrome, which is associated with renal salt wasting and hypokalemic alkalosis, is due to the defective transport of chloride ions and associated ions in the thick ascending loop of Henle. CLCNKB has been implicated.[7]

Another inherited disease that affects the kidney organs is Dent's disease, characterised by low molecular weight proteinuria and hypercalciuria where mutations in CLCN5 are implicated.[7]

Thomsen disease is associated with dominant mutations and Becker disease with recessive mutations in CLCN1.[7]

Genes

[edit]E-ClC family

[edit]| CLCA, N-terminal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | CLCA_N | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08434 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013642 | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.A.13 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Members of Epithelial Chloride Channel (E-ClC) Family (TC# 1.A.13) catalyze bidirectional transport of chloride ions. Mammals have multiple isoforms (at least 6 different gene products plus splice variants) of epithelial chloride channel proteins, catalogued into the Chloride channel accessory (CLCA) family.[8] The first member of this family to be characterized was a respiratory epithelium, Ca2+-regulated, chloride channel protein isolated from bovine tracheal apical membranes.[9] It was biochemically characterized as a 140 kDa complex. The bovine EClC protein has 903 amino acids and four putative transmembrane segments. The purified complex, when reconstituted in a planar lipid bilayer, behaved as an anion-selective channel.[10] It was regulated by Ca2+ via a calmodulin kinase II-dependent mechanism. Distant homologues may be present in plants, ciliates and bacteria, Synechocystis and Escherichia coli, so at least some domains within E-ClC family proteins have an ancient origin.

Genes

[edit]CLIC family

[edit]| Chloride intracellular ion channel | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | CLIC |

| InterPro | IPR002946 |

| TCDB | 1.A.12 |

The Chloride Intracellular Ion Channel (CLIC) Family (TC# 1.A.12) consists of six conserved proteins in humans (CLIC1, CLIC2, CLIC3, CLIC4, CLIC5, CLIC6). Members exist as both monomeric soluble proteins and integral membrane proteins where they function as chloride-selective ion channels. These proteins are thought to function in the regulation of the membrane potential and in transepithelial ion absorption and secretion in the kidney.[11] They are a member of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) superfamily.

Structure

[edit]They possess one or two putative transmembrane α-helical segments (TMSs). The bovine p64 protein is 437 amino acyl residues in length and has the two putative TMSs at positions 223-239 and 367-385. The N- and C-termini are cytoplasmic, and the large central luminal loop may be glycosylated. The human nuclear protein (CLIC1 or NCC27) is much smaller (241 residues) and has only one putative TMS at positions 30-36. It is homologous to the second half of p64.

Structural studies showed that in the soluble form, CLIC proteins adopt a GST fold with an active site exhibiting a conserved glutaredoxin monothiol motif, similar to the omega class GSTs. Al Khamici et al. demonstrated that CLIC proteins have glutaredoxin-like glutathione-dependent oxidoreductase enzymatic activity.[12] CLICs 1, 2 and 4 demonstrate typical glutaredoxin-like activity using 2-hydroxyethyl disulfide as a substrate. This activity may regulate CLIC ion channel function.[12]

Transport reaction

[edit]The generalized transport reaction believed to be catalyzed chloride channels is:

- Cl− (cytoplasm) → Cl− (intraorganellar space)

CFTR

[edit]CFTR is a chloride channel belonging to the superfamily of ABC transporters. Each channel has two transmembrane domains and two nucleotide binding domains. ATP binding to both nucleotide binding domains causes changes these domains to associate, further causing changes that open up the ion pore. When ATP is hydrolyzed, the nucleotide binding domains dissociate again and the pore closes.[13]

Pathology

[edit]Cystic fibrosis is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene on chromosome 7, the most common mutation being deltaF508 (a deletion of a codon coding for phenylalanine, which occupies the 508th amino acid position in the normal CFTR polypeptide). Any of these mutations can prevent the proper folding of the protein and induce its subsequent degradation, resulting in decreased numbers of chloride channels in the body.[citation needed] This causes the buildup of mucus in the body and chronic infections.[13]

Other chloride channels and families

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA (April 2002). "Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels". Physiological Reviews. 82 (2): 503–68. doi:10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. PMID 11917096.

- ^ Suzuki M, Morita T, Iwamoto T (January 2006). "Diversity of Cl(-) channels". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 63 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5336-4. PMC 2792346. PMID 16314923.

- ^ a b c d e Stölting G, Fischer M, Fahlke C (January 2014). "CLC channel function and dysfunction in health and disease". Frontiers in Physiology. 5: 378. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00378. PMC 4188032. PMID 25339907.

- ^ Li WY, Wong FL, Tsai SN, Phang TH, Shao G, Lam HM (June 2006). "Tonoplast-located GmCLC1 and GmNHX1 from soybean enhance NaCl tolerance in transgenic bright yellow (BY)-2 cells". Plant, Cell & Environment. 29 (6): 1122–37. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01487.x. PMID 17080938.

- ^ a b c d e Dutzler R (June 2007). "A structural perspective on ClC channel and transporter function". FEBS Letters. 581 (15): 2839–44. Bibcode:2007FEBSL.581.2839D. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.016. PMID 17452037. S2CID 6365004.

- ^ a b c d e f Accardi A, Picollo A (August 2010). "CLC channels and transporters: proteins with borderline personalities". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1798 (8): 1457–64. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.022. PMC 2885512. PMID 20188062.

- ^ a b c Planells-Cases R, Jentsch TJ (March 2009). "Chloride channelopathies" (PDF). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1792 (3): 173–89. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.02.002. PMID 19708126.

- ^ Evans SR, Thoreson WB, Beck CL (October 2004). "Molecular and functional analyses of two new calcium-activated chloride channel family members from mouse eye and intestine". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (40): 41792–800. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408354200. PMC 1383427. PMID 15284223.

- ^ Agnel M, Vermat T, Culouscou JM (July 1999). "Identification of three novel members of the calcium-dependent chloride channel (CaCC) family predominantly expressed in the digestive tract and trachea". FEBS Letters. 455 (3): 295–301. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00891-1. PMID 10437792. S2CID 82094058.

- ^ Brunetti E, Filice C (June 1996). "Percutaneous aspiration in the treatment of hydatid liver cysts". Gut. 38 (6): 936. doi:10.1136/gut.38.6.936. PMC 1383206. PMID 8984037.

- ^ Singh H, Ashley RH (2007-02-01). "CLIC4 (p64H1) and its putative transmembrane domain form poorly selective, redox-regulated ion channels". Molecular Membrane Biology. 24 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1080/09687860600927907. PMID 17453412. S2CID 9986497.

- ^ a b Al Khamici H, Brown LJ, Hossain KR, Hudson AL, Sinclair-Burton AA, Ng JP, Daniel EL, Hare JE, Cornell BA, Curmi PM, Davey MW, Valenzuela SM (2015-01-01). "Members of the chloride intracellular ion channel protein family demonstrate glutaredoxin-like enzymatic activity". PLOS ONE. 10 (1) e115699. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..10k5699A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115699. PMC 4291220. PMID 25581026.

- ^ a b Gadsby DC, Vergani P, Csanády L (March 2006). "The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis". Nature. 440 (7083): 477–83. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..477G. doi:10.1038/nature04712. PMC 2720541. PMID 16554808.

Further reading

[edit]- Schmidt-Rose T, Jentsch TJ (August 1997). "Reconstitution of functional voltage-gated chloride channels from complementary fragments of CLC-1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (33): 20515–21. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.33.20515. PMID 9252364.

- Zhang J, George AL, Griggs RC, Fouad GT, Roberts J, Kwieciński H, Connolly AM, Ptácek LJ (October 1996). "Mutations in the human skeletal muscle chloride channel gene (CLCN1) associated with dominant and recessive myotonia congenita". Neurology. 47 (4): 993–8. doi:10.1212/wnl.47.4.993. PMID 8857733. S2CID 45062016.

- Mindell JA, Maduke M (2001). "ClC chloride channels". Genome Biology. 2 (2) REVIEWS3003. doi:10.1186/gb-2001-2-2-reviews3003. PMC 138906. PMID 11182894.

- Singh H (May 2010). "Two decades with dimorphic Chloride Intracellular Channels (CLICs)". FEBS Letters. 584 (10): 2112–21. Bibcode:2010FEBSL.584.2112S. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2010.03.013. PMID 20226783. S2CID 21056278.

External links

[edit]- Chloride+channels at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- UMich Orientation of Proteins in Membranes families/superfamily-10 - CLC chloride channels

As of this edit, this article uses content from "1.A.13 The Epithelial Chloride Channel (E-ClC) Family", which is licensed in a way that permits reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, but not under the GFDL. All relevant terms must be followed. As of this edit, this article uses content from "1.A.12 The Intracellular Chloride Channel (CLIC) Family", which is licensed in a way that permits reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, but not under the GFDL. All relevant terms must be followed.

Chloride channel

View on GrokipediaOverview and Functions

Definition and distribution

Chloride channels are transmembrane proteins that facilitate the selective transport of chloride ions (Cl⁻) and other anions across cell membranes down their electrochemical gradients. Most function as passive pores allowing rapid diffusion without direct energy input, but some, particularly intracellular members of the ClC family, act as coupled Cl⁻/H⁺ antiporters.[4] These proteins play essential roles in maintaining cellular anion homeostasis, membrane potential, and volume regulation.[6] Chloride channels exhibit remarkable evolutionary conservation, with homologs identified across diverse phyla from prokaryotes, such as bacterial ClC family members like EriC in Escherichia coli, to eukaryotes including yeast, plants, and animals.[7] This ancient origin underscores their fundamental importance in anion handling, as evidenced by the presence of ClC-like proteins in nearly all organisms, where they have diversified to support specialized physiological needs while retaining core structural motifs for ion conduction.[8] In mammals, the ClC family alone comprises nine members, reflecting extensive evolutionary adaptation from simpler bacterial forms.[9] These channels are ubiquitously distributed across cell types and organisms, with expression in both excitable cells such as neurons and skeletal muscle—where they stabilize resting potentials and contribute to action potential repolarization—and in epithelial tissues like those of the lung, kidney, and intestine, facilitating transepithelial salt and fluid transport.[10] They are also prevalent in non-excitable cells, including fibroblasts, where they aid in cell volume control during osmotic stress.[11] Localization varies, with many chloride channels embedded in the plasma membrane to regulate extracellular ion balance, while others reside in intracellular compartments such as endosomes, lysosomes, and mitochondria to support organelle acidification, pH homeostasis, and ionic equilibrium.[12] Chloride channels are broadly classified by their activation mechanisms, including voltage-gated types (e.g., ClC family members like ClC-1), ligand-gated channels (e.g., GABA_A and glycine receptors), Ca²⁺-activated channels (e.g., anoctamins/TMEM16 family), swelling- or volume-activated channels (e.g., VRACs), ATP- and cAMP-regulated channels (e.g., CFTR), and intracellular Cl⁻/H⁺ antiporters (e.g., ClC-3 to ClC-7) primarily functioning in organelles.[3] This diversity allows tailored responses to cellular signals, from electrical depolarization in excitable tissues to osmotic swelling in epithelial cells.[13]Physiological roles

Chloride channels play essential roles in maintaining cellular excitability by stabilizing membrane potential, particularly through Cl⁻ influx that hyperpolarizes neurons and muscle cells, thereby influencing their excitability and preventing hyperexcitability. In skeletal muscle, these channels contribute significantly to the resting membrane conductance, accounting for 70–80% of total conductance to dampen action potential propagation and ensure efficient repolarization. In neurons, Cl⁻ influx via channels activated by inhibitory neurotransmitters like GABA and glycine hyperpolarizes the membrane, inhibiting neuronal firing in the adult central nervous system. These channels are also critical for cell volume regulation, where activation during hypotonic swelling promotes Cl⁻ efflux, facilitating regulatory volume decrease to restore osmotic balance and prevent cell lysis. In epithelial tissues, chloride channels mediate secretion and absorption of Cl⁻, driving fluid homeostasis in airways, intestines, and kidneys; for instance, CFTR facilitates Cl⁻ secretion in airway epithelia to support mucociliary clearance. Intracellularly, they contribute to signaling by regulating pH in organelles such as endosomes and lysosomes, where Cl⁻ conductance maintains electroneutrality during proton pumping by H⁺-ATPases, and by modulating enzyme activity through Cl⁻ gradients across membranes. Cytosolic Cl⁻ concentrations are typically maintained at 5–50 mM, varying by cell type, with higher levels in some organelles, to support these functions.[14] This gradient is established and regulated by secondary active transporters, including the Na⁺-K⁺-2Cl⁻ cotransporter (NKCC) for Cl⁻ influx and the K⁺-Cl⁻ cotransporter (KCC) for efflux, which work in concert with chloride channels to fine-tune intracellular Cl⁻ levels.Biophysical Properties

Selectivity and permeation

Chloride channels exhibit high selectivity for Cl⁻ ions over other anions and cations through a specialized selectivity filter in the pore. This filter commonly incorporates positively charged residues, such as lysine and arginine, which provide electrostatic attraction for anions while repelling cations, thereby facilitating Cl⁻ discrimination. The narrow pore radius of approximately 3-4 Å in the selectivity region accommodates the dehydrated Cl⁻ ion (with an ionic radius of about 1.8 Å) but restricts passage of larger hydrated ions or cations, ensuring specificity.[15][16] The permeation pathway of Cl⁻ through these channels typically involves a constricted pore that supports single-file ion movement, where Cl⁻ ions interact electrostatically with one another and with the channel walls. Within this pathway, binding sites strip part or all of the Cl⁻ hydration shell, enabling direct coordination with protein atoms such as backbone carbonyls or side-chain groups, which stabilizes the ion and promotes rapid throughput in multi-ion configurations. This dehydration step at the binding sites is essential for overcoming energy barriers to permeation while maintaining selectivity.[17][18] Single-channel conductance in chloride channels generally falls within the range of 1-100 pS, reflecting efficient ion flux under physiological conditions, with values varying by channel subtype and environmental factors. Many channels display rectification properties, such as outward rectification due to asymmetric anion concentrations or voltage-dependent interactions that favor inward or outward current flow. The overall driving force for Cl⁻ permeation is determined by the electrochemical gradient across the membrane, quantified by the Nernst reversal potential: which typically ranges from -40 to -70 mV in cellular environments, directing net Cl⁻ influx or efflux based on the membrane potential.[19][20] An intriguing feature observed in certain chloride channels is the anomalous mole fraction effect, where the conductance increases in mixtures of permeant anions (e.g., Cl⁻ and SCN⁻) compared to pure solutions at equivalent concentrations. This phenomenon arises from multi-ion pore occupancy, where electrostatic repulsion between mixed anions facilitates faster permeation than in homovalent conditions, providing evidence for cooperative ion interactions within the channel.[21]Gating and regulation

Chloride channels exhibit diverse gating mechanisms that control their opening and closing in response to cellular signals, ensuring precise regulation of chloride ion flux across membranes. Voltage gating is a prominent mechanism in many chloride channels, where membrane depolarization or hyperpolarization induces conformational changes that open the pore. For instance, in voltage-gated chloride channels like those in the CLC family, the steady-state open probability () follows the Boltzmann equation: where is the effective gating valence, is Faraday's constant, is the membrane potential, is the half-activation voltage, is the gas constant, and is temperature in Kelvin; this equation quantifies the sigmoidal voltage dependence observed in electrophysiological recordings.[22] Some channels, such as ClC-1, activate upon depolarization to stabilize membrane potential, while others like ClC-2 open with hyperpolarization to facilitate anion efflux.[6] Ligand gating occurs when specific molecules bind to the channel, triggering pore opening and chloride permeation. In ligand-gated chloride channels, such as GABA_A and glycine receptors, neurotransmitters like GABA or glycine bind to extracellular domains, inducing rapid conformational shifts that allow chloride influx for synaptic inhibition. These pentameric channels typically exhibit fast activation kinetics upon ligand binding, with desensitization following prolonged exposure.[23] Binding affinity and efficacy vary by subunit composition, enabling fine-tuned responses in neuronal signaling.[6] Additional regulators modulate chloride channel activity through intracellular and extracellular cues. Calcium ions (Ca²⁺) activate certain channels, such as anoctamins (TMEM16 family), by binding to cytosolic domains that promote voltage-dependent opening, often in secretory epithelia.[24] Extracellular pH influences gating, with acidification enhancing activity in channels like ClC-2 via protonation of key residues, aiding volume regulation during osmotic stress.[6] ATP serves as a regulator in channels like CFTR, where binding to nucleotide-binding domains, coupled with phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA), promotes opening; hydrolysis then drives closure.[25] Phosphorylation by kinases such as PKA or PKC alters gating kinetics at specific serine/threonine sites, enhancing or inhibiting activity depending on the channel. Mechanical stretch activates volume-sensitive channels, like those involved in regulatory volume decrease, through cytoskeletal interactions that widen the pore.[6] Gating kinetics span milliseconds to seconds, reflecting the physiological context: fast activation (e.g., ~1-10 ms for ligand-gated channels) enables rapid synaptic responses, while slower processes (e.g., 100 ms to seconds for voltage gating in CLC channels) support sustained regulation. Single-channel recordings reveal burst-like openings, whereas macroscopic currents show sigmoidal activation curves. Common structural motifs include ligand-binding pockets formed by extracellular loops; however, many chloride channels, like CLCs, employ atypical mechanisms involving permeation pathways for gating.[26]CLC Family

Structure and mechanism

CLC proteins of the CLC family assemble into homodimers or heterodimers, such as ClC-1/ClC-2, where each monomer operates as an independent functional unit with its own ion conduction pathway.[27] Each monomer spans the membrane with 18 transmembrane α-helices, forming a compact bundle that contributes to the overall rhombus-shaped architecture of the dimer, while the cytoplasmic C-terminal region features two cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) domains per monomer.[27] These CBS domains, absent in prokaryotic homologs, interact with the transmembrane domain and modulate protein stability, trafficking, and gating through binding to nucleotides like ATP. The pore architecture within each monomer includes a central anion permeation pathway for Cl⁻ ions and a separate proton conduction pathway along the interface between the transmembrane domains of the two subunits.[27] The anion pathway features three conserved Cl⁻ binding sites—internal (S_int), central (S_cen), and external (S_ext)—with the selectivity filter primarily formed by the SYT motif (serine, tyrosine, and threonine residues, such as S107 and Y445 in bacterial ClC-ec).[27] This filter ensures high selectivity for anions over cations through electrostatic interactions with partially positively charged residues.[27] The crystal structure of the bacterial exchanger ClC-ec (PDB: 1KPK), determined at 2.5 Å resolution, first revealed this conserved architecture and the binding of two Cl⁻ ions in the resolved structure.[27] Subsequent structures of eukaryotic CLCs, such as ClC-K and ClC-1, confirm the conservation of this transmembrane fold across the family.[28] CLC family members function either as pure Cl⁻ channels or as 2Cl⁻/H⁺ antiporters, with the distinction primarily among subtypes: ClC-1, ClC-2, ClC-Ka, and ClC-Kb act as channels permitting passive Cl⁻ conduction, while ClC-3 through ClC-7 operate as exchangers coupling Cl⁻ efflux to H⁺ influx at a 2:1 stoichiometry. In exchangers, the obligatory coupling arises from the shared permeation pathways, where proton translocation drives Cl⁻ movement without net charge transport across the membrane.[29] Channels like ClC-1 lack this strict coupling and support electrogenic Cl⁻ flow, though all CLCs retain a proton-sensitive component in their permeation. The operational mechanism relies on a protonation/deprotonation cycle that gates Cl⁻ permeation: external protons access a conserved glutamate residue (e.g., E148 in ClC-ec) via the proton pathway, facilitating Cl⁻ binding and translocation through the anion pore in a broken symmetry manner.[29] Gating occurs at two levels—fast gating at the level of the individual protopore (on the millisecond scale, voltage-dependent and modulated by the glutamate gate) and slow gating involving the dimeric interface and CBS domains (on the second scale, influenced by ATP and intracellular Cl⁻).00210-8) In exchangers, the fast gate is absent, and permeation is tightly coupled to the slower proton cycle, whereas channels exhibit independent fast gating for rapid Cl⁻ flux.Subtypes and functions

The CLC family comprises nine mammalian members, categorized into plasma membrane chloride channels (ClC-1, ClC-2, ClC-Ka, and ClC-Kb) and intracellular Cl⁻/H⁺ exchangers (ClC-3 through ClC-7), with the latter facilitating 2Cl⁻ influx per H⁺ efflux to support organelle acidification.[30][26] Among the channels, ClC-1 is predominantly expressed in skeletal muscle, where it accounts for approximately 80% of the resting chloride conductance and stabilizes the membrane potential to prevent hyperexcitability during repetitive action potentials.[30] ClC-2, widely distributed across neurons, epithelial cells, and other tissues including the brain, intestine, and lung, contributes to cell volume regulation, dampens neuronal excitability by lowering intracellular Cl⁻ concentration, and supports transepithelial Cl⁻ transport and pH homeostasis in epithelia.[30][26] The renal-specific ClC-Ka and ClC-Kb (also known as ClC-K1 and ClC-K2 in humans) are expressed in the nephron and inner ear stria vascularis; ClC-Ka mediates Cl⁻ reabsorption in the thin ascending limb of the loop of Henle, while ClC-Kb handles basolateral Cl⁻ recycling in the thick ascending limb and distal tubule, facilitating NaCl reabsorption and urine concentration, with dysfunction mimicking the effects of loop diuretics like furosemide.[30][26] The exchanger subtypes localize primarily to endolysosomal membranes. ClC-3, expressed in brain neurons, heart, kidney, and immune cells, regulates cell volume by enabling Cl⁻ accumulation and supports endosomal acidification, which is crucial for vesicular trafficking and maintaining intracellular ion homeostasis.[30] ClC-4 and ClC-5, found in neuronal and renal tissues respectively, assist in endosomal acidification and protein trafficking; ClC-4 aids synaptic vesicle function in the brain, while ClC-5 is essential for receptor-mediated endocytosis in kidney proximal tubule cells.[30][26] ClC-6 and ClC-7 are lysosomal exchangers, with ClC-6 enriched in the nervous system for late endosomal function and ClC-7 broadly distributed to support lysosomal degradation and acidification across tissues like brain, kidney, and bone-resorbing osteoclasts.[30]Associated diseases

Mutations in the CLCN1 gene, which encodes the ClC-1 chloride channel primarily expressed in skeletal muscle, are the primary cause of myotonia congenita, a hereditary muscle disorder characterized by delayed muscle relaxation and stiffness due to reduced sarcolemmal chloride conductance that leads to hyperexcitability of muscle fibers.[31] These mutations often result in loss-of-function effects, impairing the channel's ability to stabilize the resting membrane potential, with over 350 distinct variants identified across patients, including missense, nonsense, and splicing mutations that disrupt channel gating or trafficking.[32] Dominant forms, such as Thomsen's disease, typically arise from heterozygous mutations exerting dominant-negative effects, while recessive Becker's myotonia involves biallelic loss-of-function variants leading to more severe symptoms.[33] Bartter syndrome type III, also known as classic Bartter syndrome, stems from mutations in the CLCNKB gene encoding ClC-Kb, a chloride channel crucial for chloride reabsorption in the thick ascending limb and distal convoluted tubule of the kidney, resulting in salt wasting, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, and polyuria.[34] These defects impair the basolateral chloride exit, disrupting the electrochemical gradient necessary for sodium and potassium reabsorption via associated transporters, leading to milder renal symptoms compared to other Bartter subtypes but with significant growth retardation in some cases.[35] Over 100 mutations have been reported, including deletions and missense variants that abolish channel function or expression, confirming the genotype-phenotype correlation in this autosomal recessive disorder.[36] Dent's disease type 1 is caused by mutations in the CLCN5 gene, which encodes ClC-5, a chloride/proton exchanger localized to endosomal membranes in proximal tubule epithelial cells, leading to disrupted endosomal acidification and impaired receptor-mediated endocytosis that manifests as low-molecular-weight proteinuria, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and progressive renal failure.[37] These X-linked mutations, numbering over 200 distinct variants including frameshifts, nonsense, and missense changes, reduce ClC-5 conductance or trafficking, thereby hindering the recycling of megalin and cubilin receptors essential for protein reabsorption.[38] The resulting proximal tubulopathy highlights ClC-5's role in maintaining endolysosomal pH homeostasis, with functional studies showing a direct correlation between mutation severity and clinical progression.[39] Dysfunction of ClC-7, encoded by CLCN7 and functioning as a lysosomal chloride/proton antiporter critical for acidification and degradation in osteoclasts and neurons, underlies autosomal recessive osteopetrosis with associated lysosomal storage disorders and neurodegeneration due to accumulation of undegraded material in lysosomes.[40] Loss-of-function mutations impair lysosomal pH regulation, leading to defective bone resorption in osteopetrosis and progressive neuronal loss, as evidenced by animal models showing widespread storage pathology beyond the skeleton.[41] Biallelic variants disrupt the ClC-7/Ostm1 complex, exacerbating proteolysis defects and contributing to the multisystem phenotype observed in affected individuals.[42] Dysregulation of ClC-2 and ClC-3 chloride channels has been implicated in epilepsy pathogenesis, where altered chloride homeostasis in neurons and glia contributes to seizure susceptibility through disrupted inhibitory signaling and neuronal excitability.[43] Specifically, ClC-2 knockout models exhibit spontaneous seizures and neuronal degeneration, underscoring its role in maintaining resting potential and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic inhibition, while ClC-3 variants are linked to volume regulation deficits in epileptic foci.[44] A 2023 review emphasizes the underappreciated contribution of these voltage-gated chloride channels to epileptogenesis, highlighting potential therapeutic avenues via channel modulation.[43] ClC-K channels, particularly ClC-Kb, represent promising therapeutic targets in renal disorders like Bartter syndrome, with loop diuretics such as furosemide indirectly influencing ClC-K function by inhibiting upstream NKCC2 cotransport in the loop of Henle, thereby reducing chloride delivery and alleviating hypokalemia.[45] Emerging ClC-K-specific inhibitors, distinct from traditional loop diuretics, have shown diuretic efficacy in preclinical models by directly blocking chloride reabsorption, offering potential for targeted treatment of salt-wasting nephropathies without broad electrolyte disturbances.[46]Genetic encoding

The CLC family of chloride channels in humans is encoded by nine genes, designated CLCN1 through CLCN7, as well as CLCNKA and CLCNKB, which collectively form the CLCN gene family. These genes exhibit diverse chromosomal locations across the human genome. For instance, CLCN1 is situated on chromosome 7q34-q35, while CLCNKA and CLCNKB are both located on chromosome 1p36.13. The full distribution is summarized in the following table:| Gene | Chromosomal Location |

|---|---|

| CLCN1 | 7q34 |

| CLCN2 | 3q26.1-3q27 |

| CLCN3 | 4q32.1 |

| CLCN4 | Xp22.3 |

| CLCN5 | Xp11.22 |

| CLCN6 | Xp22.3 |

| CLCN7 | 16p13.3 |

| CLCNKA | 1p36.13 |

| CLCNKB | 1p36.13 |