Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

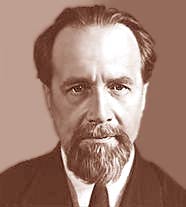

Nikolai Myaskovsky

View on Wikipedia

Nikolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky[1] (Russian: Никола́й Я́ковлевич Мяско́вский; Polish: Mikołaj Miąskowski; 20 April 1881 – 8 August 1950), was a Russian and Soviet composer. He is sometimes referred to[by whom?] as the "Father of the Soviet Symphony". Myaskovsky was awarded the Stalin Prize five times.

Key Information

Early years

[edit]Myaskovsky was born in Nowogieorgiewsk, near Warsaw, Congress Poland, Russian Empire, the son of an engineer officer in the Russian army. After the death of his mother the family was brought up by his father's sister, Yelikonida Konstantinovna Myaskovskaya, who had been a singer at the Saint Petersburg Opera. The family moved to Saint Petersburg in his teens.

Though he learned piano and violin, he was discouraged from pursuing a musical career, and entered the military. However, a performance of Tchaikovsky's Pathétique Symphony conducted by Arthur Nikisch in 1896 inspired him to become a composer. In 1902 he completed his training as an engineer, like his father. As a young subaltern with a Sappers Battalion in Moscow, he took some private lessons with Reinhold Glière and when he was posted to Saint Petersburg he studied with Ivan Krizhanovsky as preparation for entry into the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, where he enrolled in 1906 and became a student of Anatoly Lyadov and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

A late starter, Myaskovsky was the oldest student in his class but soon became firm friends with the youngest, Sergei Prokofiev, and they remained friends throughout the older man's life.[2] At the Conservatory, they shared a dislike of their professor Anatoly Lyadov, which, since Lyadov disliked the music of Edvard Grieg, led to Myaskovsky's choice of a theme by Grieg for the variations with which he closed his String Quartet No. 3.[3]

Early works

[edit]Prokofiev and Myaskovsky worked together at the conservatory on at least one work, a lost symphony, parts of which were later scavenged to provide material for the slow movement of Prokofiev's Piano Sonata No. 4. They both later produced works using materials from this period—in Prokofiev's case the Third and Fourth piano sonatas; in Myaskovsky's other works, such as his Tenth String Quartet and what are now the Fifth and Sixth Piano Sonatas, all revisions of works he wrote at this time.

Early influences on Myaskovsky's emerging personal style were Tchaikovsky, strongly echoed in the first of his surviving symphonies (in C minor, Op. 3, 1908/1921), which was his Conservatory graduation piece, and Alexander Scriabin, whose influence comes more to the fore in Myaskovsky's First Piano Sonata in D minor, Op. 6 (1907–10), described by Glenn Gould as "perhaps one of the most remarkable pieces of its time",[4] and his Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 15 of 1914, a turbulent and lugubrious work in two large movements.

Myaskovsky graduated in 1911 and afterwards taught in Saint Petersburg, where he also developed a supplementary career as a penetrating musical critic, writing for the Moscow publication, "Muzyka."[5] He was one of the most intelligent and supportive advocates in Russia for the music of Igor Stravinsky,[6] though the story that Stravinsky dedicated The Rite of Spring to Myaskovsky is untrue.[7]

Called up during World War I, he was wounded and suffered shell-shock on the Austrian front, then worked on the naval fortifications at Tallinn. During this period he produced two diametrically opposed works, his Symphony No. 4 (Op. 17, in E minor) and his Symphony No. 5 (Op. 18, in D major). The next few years saw the violent death of his father, an ex-Tsarist general who was murdered by Red Army soldiers while waiting for a train in the winter of 1918–19,[8] and the death of his aunt, to whom he was closely attached, in the winter of 1919–20. His brother-in-law, the husband of his sister Valentina Yakovlevna, had committed suicide before the War because of financial troubles.[9] Myaskovsky himself served in the Red Army from 1917 to 1921; in the latter year he was appointed to the teaching staff of the Moscow Conservatory and membership of the Composers' Union. Thereafter he lived in Moscow, sharing an apartment with his widowed sister Valentina and her daughter. (He also had a married sister, Vera.)[9]

Middle years

[edit]In the 1920s and 1930s Myaskovsky was the leading composer in the USSR dedicated to developing basically traditional, sonata-based forms. He wrote no operas—though in 1918 he planned one based on Fyodor Dostoyevsky's novel The Idiot, with a libretto by Pierre Souvtchinsky;[10] but he would eventually write a total of 27 symphonies (plus three sinfoniettas, two concertos, and works in other orchestral genres), 13 string quartets, 9 piano sonatas as well as many miniatures and vocal works. Through his devotion to these forms, and the fact that he always maintained a high standard of craftsmanship, he was sometimes referred to as 'the musical conscience of Moscow'. His continuing commitment to musical modernism was shown by the fact that along with Alexander Mosolov, Gavriil Popov and Nikolai Roslavets, Myaskovsky was one of the leaders of the Association for Contemporary Music. While he remained in close contact with Prokofiev during the latter's years of exile from the USSR, he never followed him there.

Myaskovsky's reaction to the events of 1917–21 inspired his Symphony No. 6 (1921–1923, rev. 1947—this is the version that is almost always played or recorded) his only choral symphony and the longest of his 27 symphonies, sets a brief poem (in Russian though the score allows Latin alternatively—see the American Symphony Orchestra page below on the origins of the poem—the soul looking at the body it has abandoned.) The finale contains quite a few quotes—the Dies Irae theme, as well as French revolutionary tunes.[citation needed]

The years 1921–1933, the first years of his teaching at the Moscow Conservatory, were the years in which he experimented most, producing works such as the Tenth and Thirteenth symphonies, the fourth piano sonata and his first string quartet. Perhaps the best example of this experimental phase is the Thirteenth symphony, which was the only one of his works to be premiered in the United States.

In the 1920s and 1930s Myaskovsky's symphonies were quite frequently played in Western Europe and the USA. His works were issued by Universal Edition, one of Europe's most prestigious publishers.[11] In 1935, a survey made by CBS of its radio audience asking the question "Who, in your opinion, of contemporary composers will remain among the world's great in 100 years?" placed Myaskovsky in the top ten along with Prokofiev, Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Richard Strauss, Stravinsky, Sibelius, Ravel, de Falla and Fritz Kreisler.[12]

The next few years after 1933 are characterized mostly by his apparent discontinuation of his experimental trend, though with no general decrease in craftsmanship. The Violin Concerto dates from these years, the first of two or three concerti, depending on what one counts, the second being for cello, and a third if one counts the Lyric Concertino, Op. 32 as a concerto work.

Another work from the period up to 1940 is the one-movement Symphony No. 21 in F-sharp minor, Op. 51, a compact and mostly lyrical work, very different in harmonic language from the Thirteenth.

Despite his personal feelings about the Stalinist regime, Myaskovsky did his best not to engage in overt confrontation with the Soviet state. While some of his works refer to contemporary themes, they do not do so in a programmatic or propagandistic way. The Symphony No. 12 was inspired by a poem about the collectivization of farming, while No. 16 was prompted by the crash of the huge airliner Maxim Gorky and was known under the Soviets as the Aviation Symphony. This symphony, sketched immediately after the disaster and premiered in Moscow on 24 October 1936, includes a big funeral march as its slow movement, and the finale is built on Myaskovsky's own song for the Red Air Force, 'The Aeroplanes are Flying'. The Salutation Overture was dedicated to Stalin on his sixtieth birthday.

Final decade

[edit]The year 1941 saw Myaskovsky evacuated, along with Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian among others, to what were then the Kabardino-Balkar regions. There he completed the Symphony-Ballade (Symphony No. 22) in B minor, inspired in part by the first few months of the war. Prokofiev's Second String Quartet and Myaskovsky's Symphony No. 23 and Seventh String Quartet contain themes in common—they are Kabardinian folk-tunes the composers took down during their sojourn in the region. The sonata-works (symphonies, quartets, etc.) written after this period and into the post-war years (especially starting with the Symphony No. 24, the piano sonatina, the Ninth Quartet) while Romantic in tone and style, are direct in harmony and development. He does not deny himself a teasingly neurotic scherzo, as in his last two string quartets (that in the Thirteenth Quartet, his last published work, is frantic, and almost chiaroscuro but certainly contrasted) and the general paring down of means usually allows for direct and reasonably intense expression, as with the Cello Concerto (dedicated to and premiered by Sviatoslav Knushevitsky) and Cello Sonata No. 2 (dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich).

While not particularly experimental, there is no suggestion—as with some earlier works—that Alexander Scriabin or Arnold Schoenberg might still have been influences. In 1947 Myaskovsky was singled out, with Shostakovich, Khachaturian and Prokofiev, as one of the principal offenders in writing music of anti-Soviet, 'anti-proletarian' and formalist tendencies. Myaskovsky refused to take part in the proceedings, despite a visit from Tikhon Khrennikov inviting him to deliver a speech of repentance at the next meeting of the Composers' Union.[12] He was rehabilitated only after his death from cancer in 1950, leaving an output of eighty-seven published opus numbers spanning some forty years, and students with recollections.

Legacy

[edit]Character and influence

[edit]Myaskovsky was long recognized as an individualist, even by the Soviet establishment. In the 1920s the critic Boris Asafyev commented that he was "not the kind of composer the Revolution would like; he reflects life not through the feelings and spirit of the masses, but through the prism of his personal feelings. He is a sincere and sensible artist, far from 'life's enemy', as he has been portrayed occasionally. He speaks not only for himself, but for many others".[12]

Myaskovsky never married and was shy, sensitive and retiring; Pierre Souvtchinsky believed that a "brutal youth (in military school and service in the war)" left him "a fragile, secretive, introverted man, hiding some mystery within. It was as if his numerous symphonies provide a convenient if not necessary refuge in which he could hide and transpose his soul into sonorities".[12]

Stung by the many accusations in the Soviet press of "individualism, decadence, pessimism, formalism and complexity", Myaskovsky wrote to Asafyev in 1940, "Can it be that the psychological world is so foreign to these people?"[12] When somebody described Zhdanov's decree against "formalism" to him as "historic", he is reported to have retorted "Not historic – hysterical".[13] Shostakovich, who visited Myaskovsky on his deathbed, described him afterwards to the musicologist Marina Sabinina as "the most noble, the most modest of men".[14] Mstislav Rostropovich, for whom Myaskovsky wrote his Second Cello Sonata late in life, described him as "a humorous man, a sort of real Russian intellectual, who in some ways resembled Turgenev".[14]

Myaskovsky exercised an important influence on his many pupils, as a professor of composition at the Moscow Conservatory from 1921 until his death. The young Shostakovich considered leaving Leningrad to study with him. His students included Aram Khachaturian, Dmitri Kabalevsky, Varvara Gaigerova, Vissarion Shebalin, Rodion Shchedrin, German Galynin, Andrei Eshpai, Alexei Fedorovich Kozlovsky, Alexander Lokshin, Boris Tchaikovsky, and Evgeny Golubev.

The degree and nature of his influence on his students is difficult to measure. What is lacking is an account of his teaching methods, what and how he taught, or more than brief accounts of his teaching; Shchedrin makes a mention in an interview he did for the American music magazine Fanfare. It has been said that the earlier music of Khachaturian, Kabalevsky and other of his students has a Myaskovsky flavor, with this quality decreasing as the composer's own voice emerges (since Myaskovsky's own output is internally diverse such a statement needs further clarification)[15]—while some composers, for instance the little-heard Evgeny Golubev, kept something of his teacher's characteristics well into their later music. The latter's sixth piano sonata is dedicated to Myaskovsky's memory and the early "Symphony No. 0" of Golubev's pupil Alfred Schnittke, released on CD in 2007, has striking reminiscences of Myaskovsky's symphonic style and procedures.[citation needed]

Recordings

[edit]Myaskovsky has not been as popular on recordings as have Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Nonetheless, most of his works have been recorded, many of them more than once, including the Cello Concerto, the Violin Concerto, many of the Symphonies, and much of his chamber and solo music.

Between 1991 and 1993 the conductor Yevgeny Svetlanov realized a massive project to record Myaskovsky's entire symphonic output and most of his other orchestral works on 16 CDs,[16] with the Symphony Orchestra of the USSR and the State Symphony Orchestra of the Russian Federation. In the chaotic conditions prevailing at the breakup of the USSR, Svetlanov is rumoured to have had to pay the orchestral musicians himself in order to undertake the sessions. The recordings began to be issued in the West by Olympia Records in 2001, but ceased after volume 10; the remaining volumes were issued by Alto Records starting in the first half of 2008. To complicate matters, in July 2008, Warner Music France issued the entire 16-CD set, boxed, as volume 35 of their 'Édition officielle Evgeny Svetlanov'.

In a testimony printed in French and English in the accompanying booklet, Svetlanov describes Myaskovsky as "the founder of Soviet symphonism, the creator of the Soviet school of composition, the composer whose work has become the bridge between Russian classics and Soviet music ... Myaskovsky entered the history of music as a great toiler like Haydn, Mozart and Schubert. ... He invented his own style, his own intonations and manner while enriching and developing the glorious tradition of Russian music". Svetlanov also likens the current neglect of Myaskovsky's symphonies to the neglect formerly suffered by the symphonies of Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner.[17]

Advocates

[edit]One of Myaskovsky's strongest early advocates was the conductor Konstantin Saradzhev. He conducted the premieres of Myaskovsky's 8th,[18] 9th[19] and 11th[20] symphonies and the symphonic poem Silence, Op. 9 (which was dedicated to Saradzhev).[20] The 10th Symphony was also dedicated to Saradzhev.[20] In 1934 Myaskovsky wrote a Preludium and Fughetta on the name Saradzhev (for orchestra, Op. 31H; he also arranged it for piano 4-hands, Op. 31J).[20]

In the 1930s, Myaskovsky was also one of two Russian composers championed by Frederick Stock, the conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The other was Reinhold Glière, whom he met in 1940 and commissioned to write his "Feast in Fergana", Op. 75, a large-scale orchestral fantasia.

Stock met Myaskovsky in March 1938 at the invitation of the Composers Union. He commissioned Myaskovsky's 21st Symphony (Symphony-Fantasy in F-sharp minor) for the Chicago Symphony's Fiftieth Anniversary. The first performance was in Moscow on 6 November 1940 (conducted by Aleksandr Gauk); Stock conducted the Chicago premiere on 26 December 1940.

Honours and awards

[edit]

- 1916 – Glinka prize (shared, 350 rubles) for Piano Sonata No. 2

- 1941 – first class for Symphony No. 21

- 1946 – first class for String Quartet No. 9

- 1946 – first class for Concerto for Cello and Orchestra

- 1950 – second class for Sonata No. 2 for cello and piano

- 1951 (posthumous) – first class for Symphony No. 27 and String Quartet No. 13.

List of works

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Also transliterated as Miaskovsky or Miaskowsky

- ^ Their collected correspondence, which has not been translated into English and is said (e.g. in the Volkov Testimony[better source needed]), to have been heavily bowdlerized as regards political content, was published in 1977 as S. S. Prokofiev i N. Ya. Myaskovsky Perepiska (Moscow: Sovyetskii Kompozitor) edited by a committee with Dmitri Kabalevsky at its head. See also Sergey Prokofiev Diaries 1907–1914: Prodigious Youth translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips (London: Faber & Faber, 2006).

- ^ The quartet was probably not his third in order of composition, but eventually it was so published. The Third and Fourth string quartets share Opus 33 with the Quartets Nos. 1 and 2, and were first published together with them in the collected edition published after the composer's death, whether or not they were first published around the same time. These works - No. 3 in D minor, and No. 4 in F minor - are mid-1930s revisions of works written in the 1900s decade, not new works as are the other two; so their style is quite different.

- ^ Glenn Gould, 'Music in the Soviet Union', in A Glenn Gould Reader edited by Tim Page (London: Faber & Faber, 1987), p. 179.

- ^ "История еженедельника «Музыка» 1910–1916 гг.: документы и личности". vestnik.journ.msu.ru. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ See Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, pp. 229, 644, 762 and elsewhere.

- ^ Taruskin, pp. 1018–1019.

- ^ Andrew Stewart, notes to Cello Classics CC1012, p. 4.

- ^ a b Sergei Prokofiev, Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings translated and edited by Oleg Prokofiev (London: Faber & Faber, 1991, ISBN 0-571-16158-8), p. 37.

- ^ Taruskin, p. 1124. According to Prokofiev's diaries, Myaskovsky suggested The Idiot to Prokofiev as an opera subject in October 1913. See Sergey Prokofiev Diaries 1907–1914: Prodigious Youth translated & annotated by Anthony Phillips (London: Faber & Faber, 2006, ISBN 978-0-571-22629-0), p.525.

- ^ Taruskin, Richard (3 November 2002). "For Russian Music Mavens, a Fabled Beast Is Bagged". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Manashyr Yakubov, liner notes to Claves CD 50-9415.

- ^ Per Skans, liner notes to Alto ALC 1022.

- ^ a b Wilson, Elizabeth (2006). Shostakovich: A Life Remembered. Princeton University Press. pp. 293–4. ISBN 9780691128863.

- ^ See this Archived 13 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine biographical essay on Kabalevsky's music for a case in point

- ^ Many of them, it seems, premiere recordings in any wide distribution form. A few works do lack. An overture for orchestra, opus 9a – which originated as a piano sonata during his conservatory years... – does not appear in the series, but appears separately from the same conductor and orchestra on another record label. There also seem to be some brief works for wind band missing (e.g. some Military Marches from 1930 and 1941, the Dramatic Overture for winds Opus 60), though these are not works for full orchestra. Only the second, most often heard version of his violin concerto is included, but the first version can be heard – and compared – in the recording of the work's premiere in a Brilliant Classics CD set.

- ^ 'Evgeny Svetlanov remembers', booklet note with Warner Music France 2564 69689-8. The non-idiomatic English version has been corrected in this quotation by reference to the French version.

- ^ Review of CD with compositions by Myaskovsky Archived 13 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Barnett, Rob (November 2002). "Nikolai MIASKOVSKY (1881-1950): The Complete Symphonic Works: Volumes 6 - 9 on OLYMPIA". Music Web International.

- ^ a b c d Compositions by Nikolai Myaskovsky Archived 10 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Alexei Ikonnikov, Myaskovsky: his life and work. Translated from the Russian. New York: Philosophical Library, 1946. Reprinted by Greenwood Press, 1969, ISBN 0-8371-2158-2.

- Harlow Robinson, Sergei Prokofiev: A Biography, ISBN 1-55553-517-8 (new paperback edition)—referred to in main text.

- David Fanning, liner notes to Myaskovsky: Symphony No.6, Deutsche Grammophon 289 471 655–2.

- Malcolm MacDonald, liner notes to Myaskovsky: Symphony No.6, Warner 2564 63431-2.

- Philip Taylor, liner notes to Myaskovsky: Symphony No.27, Cello Concerto, Chandos 10025.

- Andrew Huth, liner notes to Tchaikovsky & Myaskovsky: Violin Concertos, Philips 289 473 343–2.

- Gregor Tassie, Myaskovsky and his recordings, Classical Record Quarterly, summer, 2012.

- Gregor Tassie, Myaskovsky, Musical Opinion, October 2012.

- Gregor Tassie, Nikolay Myaskovsky: the conscience of Russian music, Scarecrow Press/Rowman & Littlefield, summer 2014. ISBN 1-4422-3132-7.

- Gulinskaya, Zoya K. (1981, 1985). Nikolai Jakowlewitsch Mjaskowski (Russian, translated (by Dieter Lehmann; Ernst Kuhn) into German). Moskva: Izd-vo Muzyka / Berlin: Verlag Neue Musik. OCLC 10274227 ; OCLC 14401889.

- Patrick Zuk, Nikolay Myaskovsky: A Composer and his Times, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2021 ISBN 978-1-78327-575-5

External links

[edit]- Free scores by Nikolai Myaskovsky at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Pritsker, Maya (13 December 2000). "Nikolai Myaskovsky: Symphony No. 6, Op. 23 (1923)". American Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Detailed article about Myaskovsky and his works

- Nikolai Myaskovsky at AllMusic