Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

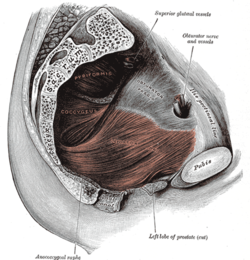

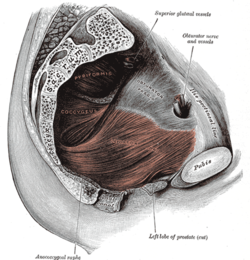

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

View on Wikipedia

| Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) | |

|---|---|

| Other names | chronic nonbacterial prostatitis, prostatodynia, painful prostate |

| |

| Specialty | Urology |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Bacterial prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, overactive bladder, cancer[2] |

| Frequency | ~4%[3] |

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS), previously known as chronic nonbacterial prostatitis, is long-term pelvic pain and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) without evidence of a bacterial infection.[3] It affects about 2–6% of men.[3] Together with IC/BPS, it makes up urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS).[4]

The cause is unknown.[1] Diagnosis involves ruling out other potential causes of the symptoms such as bacterial prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, overactive bladder, and cancer.[2][5]

Recommended treatments include multimodal therapy, physiotherapy, and a trial of alpha blocker medication or antibiotics in certain newly diagnosed cases.[6] Some evidence supports some non medication based treatments.[7]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is characterized by pelvic or perineal pain without evidence of urinary tract infection,[8] lasting longer than 3 months,[9] as the key symptom. Symptoms may wax and wane. Pain can range from mild to debilitating. Pain may radiate to the back and rectum, making sitting uncomfortable. Pain can be present in the perineum, testicles, tip of penis, pubic or bladder area.[10] Dysuria, arthralgia, myalgia, unexplained fatigue, abdominal pain, constant burning pain in the penis, and frequency may all be present. Frequent urination and increased urgency may suggest interstitial cystitis (inflammation centred in bladder rather than prostate). Post-ejaculatory pain, mediated by nerves and muscles, is a hallmark of the condition.[11]

Cause

[edit]The cause is unknown.[1] However, there are several theories of causation.

Pelvic floor dysfunction

[edit]One theory is that CP/CPPS is a psychoneuromuscular (psychological, neurological, and muscular) disorder.[12] The theory proposes that anxiety or stress results in chronic, unconscious contraction of the pelvic floor muscles, leading to the formation of trigger points and pain.[12] The pain results in further anxiety and thus worsening of the condition.[12]

Nerves, stress and hormones

[edit]Another proposal is that it may result from an interplay between psychological factors and dysfunction in the immune, neurological, and endocrine systems.[13]

A 2016 review suggested that although the peripheral nervous system is responsible for starting the condition, the central nervous system (CNS) is responsible for continuing the pain even without continuing input from the peripheral nerves.[14]

Theories behind the disease include stress-driven hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysfunction and adrenocortical hormone (endocrine) abnormalities,[15][16][17] and neurogenic inflammation.[18][19][20]

The role of androgens is studied in CP/CPPS,[21] with C

21 11-oxygenated steroids (pregnanes) are presumed to be precursors to potent androgens.[15] Specifically, steroids like 11β-hydroxyprogesterone (11OHP4) and 11-ketoprogesterone (11KP4) can be converted to 11-ketodihydrotestosterone (11KDHT), an 11-oxo form of DHT with the same potency. The relationship between steroid serum levels and CP/CPPS suggests that deficiencies in the enzyme CYP21A2 may lead to increased biosynthesis of 11-oxo androgens and androgens biosynthesized via a backdoor pathway,[22] that contribute to the development of CP/CPPS. Non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) resulting from CYP21A2 deficiency is typically considered asymptomatic in men. However, non-classical CAH could be a comorbidity associated with CP/CPPS.[23][16][17]

Bacterial infection

[edit]The bacterial infection theory was shown to be unimportant in a 2003 study which found that people with and without the condition had equal counts of similar bacteria colonizing their prostates.[24][25]

Overlap with IC/PBS

[edit]In 2007 the NIDDK began to group IC/PBS (Interstitial Cystitis & Painful Bladder Syndrome)and CP/CPPS under the umbrella term Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes (UCPPS). Therapies shown to be effective in treating IC/PBS, such as quercetin,[26] have also shown some efficacy in CP/CPPS.[27] Recent research has focused on genomic and proteomic aspects of the related conditions.[28]

People may experience pain with bladder filling, which is also a typical sign of IC.[29]

The Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Research Network has found that CPPS and bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC) are related conditions.[30]

UCPPS is a term adopted by the network to encompass both IC/BPS and CP/CPPS, which are proposed as related based on their similar symptom profiles. In addition to moving beyond traditional bladder- and prostate-specific research directions, MAPP Network scientists are investigating potential relationships between UCPPS and other chronic conditions that are sometimes seen in IC/PBS and CP/CPPS patients, such as irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome.

— The MAPP Network

Diagnosis

[edit]There are no definitive diagnostic tests for CP/CPPS. It is a poorly understood disorder, even though it accounts for 90–95% of prostatitis diagnoses.[31] CP/CPPS may be inflammatory (Category IIIa) or non-inflammatory (Category IIIb), based on levels of pus cells in expressed prostatic secretions (EPS), but these subcategories are of limited use clinically. In the inflammatory form, urine, semen, and other fluids from the prostate contain pus cells (dead white blood cells or WBCs), whereas in the non-inflammatory form no pus cells are present. Recent studies have questioned the distinction between categories IIIa and IIIb, since both categories show evidence of inflammation if pus cells are ignored and other more subtle signs of inflammation, like cytokines, are measured.[32]

In 2006, Chinese researchers found that men with categories IIIa and IIIb both had significantly and similarly raised levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine TGFβ1 and pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ in their EPS when compared with controls; therefore measurement of these cytokines could be used to diagnose category III prostatitis.[33] A 2010 study found that nerve growth factor could also be used as a biomarker of the condition.[34]

For CP/CPPS patients, analysis of urine and expressed prostatic secretions for leukocytes is debatable, especially due to the fact that the differentiation between patients with inflammatory and non-inflammatory subgroups of CP/CPPS is not useful.[35] Serum PSA tests, routine imaging of the prostate, and tests for Chlamydia trachomatis and Ureaplasma provide no benefit for the patient.[35]

Extraprostatic abdominal/pelvic tenderness is present in >50% of patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome but only 7% of controls.[36] Healthy men have slightly more bacteria in their semen than men with CPPS.[37] The high prevalence of WBCs and positive bacterial cultures in the asymptomatic control population raises questions about the clinical usefulness of the standard Meares–Stamey four-glass test as a diagnostic tool in men with CP/CPPS.[37] By 2000, the use of the four-glass test by American urologists was rare, with only 4% using it regularly.[38]

Men with CP/CPPS are more likely than the general population to have Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)[39] and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Experimental tests that could be useful in the future include tests to measure semen and prostate fluid cytokine levels. Various studies have shown increases in markers for inflammation such as elevated levels of cytokines,[40][41] myeloperoxidase,[42] and chemokines.[43]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Some conditions have similar symptoms to chronic prostatitis: bladder neck hypertrophy and urethral stricture may both cause similar symptoms through urinary reflux (inter alia) and can be excluded through flexible cystoscopy and urodynamic tests.[44][45][46]

Nomenclature

[edit]A distinction is sometimes made between "IIIa" (Inflammatory) and "IIIb" (Noninflammatory) forms of CP/CPPS,[47] depending on whether pus cells (WBCs) can be found in the expressed prostatic secretions (EPS) of the patient. Some researchers have questioned the usefulness of this categorisation, calling for the Meares–Stamey four-glass test to be abandoned.[48]

In 2007, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) began using the umbrella term urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS), for research purposes, to refer to pain syndromes associated with the bladder (i.e. interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, IC/PBS) and the prostate gland (i.e. chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, CP/CPPS).[49]

Older terms for this condition are "prostatodynia" (prostate pain) and non-bacterial chronic prostatitis. These terms are no longer in use.[50]

Symptom classification

[edit]A classification system called "UPOINT" was developed by urologists Shoskes and Nickel to allow clinical profiling of a patient's symptoms into six broad categories:[51]

- Urinary symptoms

- Psychological dysfunction

- Organ-specific symptoms

- Infectious causes

- Neurologic dysfunction

- Tenderness of the pelvic floor muscles[52]

The UPOINT system allows for individualized and multimodal therapy.[53]

Treatment

[edit]Chronic pelvic pain syndrome is difficult to treat.[54] Initial recommendations include education regarding the condition, stress management, and behavioral changes.[55]

Non-drug treatments

[edit]Current guidelines by the European Association of Urology include:[56]

- Pain education: conversation with the patient about pain, its causes and impact.

- Physical therapy: some protocols focus on stretches to release overtensed muscles in the pelvic or anal area (commonly referred to as trigger points) including intrarectal digital massage of the pelvic floor, physical therapy to the pelvic area, and progressive relaxation therapy to reduce causative stress.[54] A device, that is typically placed in the rectum, has also been created for use together with relaxation.[57] This process has been called the Stanford protocol or the Wise-Anderson protocol.[57] The American Urological Association in 2014 listed manual physical therapy as a second line treatment.[55] Kegel exercises are not recommended.[55] Treatment may also include a program of "paradoxical relaxation" to prevent chronic tensing of the pelvic musculature.[12]

- Psychological therapy: as most chronic pain conditions, psychotherapy might be helpful in its management regardless its direct impact on pain.[58][59]

Other non-drug treatments that have been evaluated for this condition include acupuncture, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, programs for physical activity, transrectal thermotherapy and a different set of recommendations regarding lifestyle changes.[7] Acupuncture probably leads to a decrease in prostatitis symptoms when compared with standard medical therapy but may not reduce sexual problems.[7] When compared with a simulated procedure, extracorporeal shockwave therapy also appears to be helpful in decreasing prostate symptoms without the impact of negative side effects but the decrease may only last while treatment is continued. As of 2018 use of extracorporeal shockwave therapy had been studied as a potential treatment for this condition in three small studies; there were short term improvements in symptoms and few adverse effects, but the medium terms results are unknown, and the results are difficult to generalize due to low quality of the studies.[7] Physical activity may slightly reduce physical symptoms of chronic prostatitis but may not reduce anxiety or depression. Transrectal thermotherapy, where heat is applied to the prostate and pelvic muscle area, on its own or combined with medical therapy may cause symptoms to decrease slightly when compared with medical therapy alone.[7] However, this method may lead to transient side effects. Alternative therapies like prostate massage or lifestyle modifications may or may not reduce symptoms of prostatitis.[7] Transurethral needle ablation of the prostate has been shown to be ineffective in trials.[60]

Neuromodulation has been explored as a potential treatment option for some time. Traditional spinal cord stimulation, also known as dorsal column stimulation has been inconsistent in treating pelvic pain: there is a high failure rate with these traditional systems due to the inability to affect all of the painful areas and there remains to be consensus on where the optimal location of the spinal cord this treatment should be aimed. As the innervation of the pelvic region is from the sacral nerve roots, previous treatments have been aimed at this region; however pain pathways seem to elude treatment solely directed at the level of the spinal cord (perhaps via the sympathetic nervous system) leading to failures.[61] Spinal cord stimulation aimed at the mid- to high-thoracic region of the spinal cord have produced some positive results. A newer form of spinal cord stimulation called dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRG) has shown a great deal of promise for treating pelvic pain due to its ability to affect multiple parts of the nervous system simultaneously – it is particularly effective in patients with "known cause" (i.e. post surgical pain, endometriosis, pudendal neuralgia, etc.).[62][63]

Medications

[edit]A number of medications can be used which need to be tailored to each person's needs and types of symptoms (according to UPOINTS, S = sexual: e.g. erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction, postorgasmic pain).[56]

- Treatment with antibiotics is controversial. A review from 2019 indicated that antibiotics may reduce symptoms. Some have found benefits in symptoms,[64][65] but others have questioned the utility of a trial of antibiotics.[66] Antibiotics are known to have anti-inflammatory properties and this has been suggested as an explanation for their partial efficacy in treating CPPS.[25] Antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines and macrolides have direct anti-inflammatory properties in the absence of infection, blocking inflammatory chemical signals (cytokines) such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which coincidentally are the same cytokines found to be elevated in the semen and EPS of men with chronic prostatitis.[67] The UPOINT diagnostic approach suggests that antibiotics are not recommended unless there is clear evidence of infection.[52]

- The effectiveness of alpha blockers (tamsulosin, alfuzosin) is questionable in men with CPPS and may increase side effects like dizziness and low blood pressure.[64] A 2006 meta-analysis found that they are moderately beneficial when the duration of therapy was at least three months.[68]

- An estrogen reabsorption inhibitor such as mepartricin improves voiding, reduces urological pain and improves quality of life in patients with chronic non-bacterial prostatitis.[69]

- Phytotherapeutics such as quercetin and flower pollen extract have been studied in small clinical trials.[70][71] A 2019 review found that this type of therapy may reduce symptoms of CPPS without side effects, but may not improve sexual problems.[64]

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors probably help to reduce prostatitis symptoms in men with CPSS and don't appear to cause more side effects than when a placebo is taken.[64]

- Anti-inflammatory drugs may reduce symptoms and may not lead to associated side effects.[64]

- When injected into the prostate, Botulinum toxin A (BTA) may cause a large decrease in prostatitis symptoms. If BTA is applied to the muscles of the pelvis, it may not lead to the reduction of symptoms. For both of these procedures, there may be no associated side effects.[64]

- For men with CPPS, taking allopurinol may give little or no difference in symptoms but also may not cause side effects.[64]

- Traditional Chinese medicine may not lead to side effects and may reduce symptoms for men with CPPS. However, these medicines probably don't improve sexual problems or symptoms of anxiety and depression.[64]

- Therapies that have not been properly evaluated in clinical trials although there is supportive anecdotal evidence include gabapentin, benzodiazepines and amitriptyline.[72]

- Diazepam suppositories are a controversial treatment for CPPS – proponents believe that by delivering the medication in a closer proximity to the area of pain that better relief can be achieved. This has never been substantiated in any research and this hypothesis is invalid due to the fact that benzodiazepines act on the GABA receptor which is present in the central nervous system. This means that regardless of the route of administration (oral versus rectal/intra-vaginal), the drug will still need to travel to the central nervous system to work and is no more or less effective when given in this capacity. Research shows this method of delivery takes longer to achieve peak effect, lower bioavailability and lower peak serum plasma concentration.[73]

Emerging research

[edit]In a preliminary 2005 open label study of 16 treatment-recalcitrant CPPS patients, controversial entities known as nanobacteria were proposed as a cause of prostatic calcifications found in some CPPS patients.[74] Patients were given EDTA (to dissolve the calcifications) and three months of tetracycline (a calcium-leaching antibiotic with anti-inflammatory effects,[75] used here to kill the "pathogens"), and half had significant improvement in symptoms. Scientists have expressed strong doubts about whether nanobacteria are living organisms,[76] and research in 2008 showed that "nanobacteria" are merely tiny lumps of abiotic limestone.[77][78]

The evidence supporting a viral cause of prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome is weak. Single case reports have implicated herpes simplex virus (HSV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV), but a study using PCR failed to demonstrate the presence of viral DNA in patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome undergoing radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer.[79] The reports implicating CMV must be interpreted with caution, because in all cases the patients were immunocompromised.[80][81][82] For HSV, the evidence is weaker still, and there is only one reported case, and the causative role of the virus was not proven,[83] and there are no reports of successful treatments using antiviral drugs such as aciclovir.

Due to the concomitant presence of bladder disorders, gastrointestinal disorders and mood disorders, research has been conducted to understand whether CP/CPPS might be caused by problems with the hypothetical bladder-gut-brain axis.[84]

Research has been conducted to understand how chronic bladder pain affects the brain, using techniques like MRI and functional MRI; as of 2016, it appeared that males with CP/CPPS have increased grey matter in the primary somatosensory cortex, the insular cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex and in the central nucleus of the amygdala; studies in rodents have shown that blocking the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5, which is expressed in the central nucleus of the amygdala, can block bladder pain.[14]

Prognosis

[edit]In recent years, the prognosis for CP/CPPS has improved with the advent of multimodal treatment, phytotherapy, protocols aimed at quieting the pelvic nerves through myofascial trigger point release, anxiety control and chronic pain therapy.[85][86][87]

Epidemiology

[edit]In the general population, chronic pelvic pain syndrome occurs in about 0.5% of men in a given year.[88] It is found in men of any age, with the peak incidence in men aged 35–45 years.[89] However, the overall prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS is 6.3%.[90] Further evidence suggests that the prevalence of CPPS-like symptoms in teenage males may be much higher than once suspected. However, this may not mean that CPPS is common in teenagers, as other conditions, such as sexually transmitted diseases, may be a more common cause of CPPS-like symptoms in this age group.[91]

The role of the prostate was questioned in the cause of CP/CPPS when both men and women in the general population were tested using the (1) National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI[92]) – with the female homologue of each male anatomical term used on questionnaires for female participants – (2) the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and (3) additional questions on pelvic pain. The prevalence of symptoms suggestive of CPPS in this selected population was 5.7% in women and 2.7% in men, placing in doubt the role of the prostate gland.[93]

Society and culture

[edit]Notable cases have included:

- John Anderson – Deputy Prime Minister of Australia[94]

- James Boswell – author of Life of Samuel Johnson[95]

- John Cleese – British actor[96]

- Vincent Gallo – movie director[97]

- Glenn Gould – pianist[98]

- John F. Kennedy – President of the United States[99]

- Tim Parks – British novelist, translator and author.[100][101]

- Howard Stern – radio personality[102][103]

- William Styron – author (Sophie's Choice)[104]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Franco JV, Turk T, Jung JH, Xiao YT, Iakhno S, Garrote V, et al. (12 May 2018). "Non-pharmacological interventions for treating chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (5) CD012551. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012551.pub3. PMC 6494451. PMID 29757454.

- ^ a b Doiron RC, Nickel JC (June 2018). "Evaluation of the male with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (6 Suppl 3): S152 – S154. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5322. PMC 6040610. PMID 29875039.

- ^ a b c Doiron RC, Nickel JC (June 2018). "Management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (6 Suppl 3): S161 – S163. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5325. PMC 6040620. PMID 29875042.

- ^ Adamian L, Urits I, Orhurhu V, Hoyt D, Driessen R, Freeman JA, et al. (May 2020). "A Comprehensive Review of the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 24 (6) 27. doi:10.1007/s11916-020-00857-9. PMID 32378039. S2CID 218513050.

- ^ Holt JD, Garrett WA, McCurry TK, Teichman JM (2016). "Common Questions About Chronic Prostatitis". Am Fam Physician. 93 (4): 290–296. PMID 26926816.

- ^ Ferri FF (2018). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2019 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1149. ISBN 978-0-323-55076-5. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Franco JV, Turk T, Jung JH, Xiao YT, Iakhno S, Garrote V, et al. (12 May 2018). "Non-pharmacological interventions for treating chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (5) CD012551. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012551.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6494451. PMID 29757454.

- ^ Schaeffer AJ (2007). "Epidemiology and evaluation of chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 31: S108 – S111. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.08.027. PMID 18164597.

- ^ Luzzi GA (2002). "Chronic prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain in men: aetiology, diagnosis and management". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 16 (3): 253–256. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00481.x. PMID 12195565. S2CID 5748689.

- ^ Clemens, J Quentin, Meenan, Richard T, O'Keeffe Rosetti, Maureen C, Gao, Sara Y, Calhoun, Elizabeth A (December 2005). "Incidence and clinical characteristics of National Institutes of Health type III prostatitis in the community". J Urol. 174 (6): 2319–2322. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000182152.28519.e7. PMID 16280832.

- ^ Shoskes DA, Landis JR, Wang Y, Nickel JC, Zeitlin SI, Nadler R (August 2004). "Impact of post-ejaculatory pain in men with category III chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". J. Urol. 172 (2): 542–547. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000132798.48067.23. PMID 15247725.

- ^ a b c d Anderson RU, Wise D, Nathanson NH (October 2018). "Chronic Prostatitis and/or Chronic Pelvic Pain as a Psychoneuromuscular Disorder – A Meta-analysis". Urology. 120: 23–29. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2018.07.022. PMID 30056195. S2CID 51864355.

- ^ Pontari MA, Ruggieri MR (May 2008). "Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". J. Urol. 179 (5 Suppl): S61 – S67. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.139. PMC 3591463. PMID 18405756.

- ^ a b Sadler KE, Kolber BJ (July 2016). "Urine Trouble: Alterations in Brain Function Associated with Bladder Pain". The Journal of Urology. 196 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.10.198. PMC 4914416. PMID 26905019.

- ^ a b Dimitrakov J, Joffe HV, Soldin SJ, Bolus R, Buffington CA, Nickel JC (2008). "Adrenocortical hormone abnormalities in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Urology. 71 (2): 261–266. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.025. PMC 2390769. PMID 18308097.

- ^ a b Masiutin MG, Yadav MK (2022). "Letter to the editor regarding the article "Adrenocortical hormone abnormalities in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome"". Urology. 169: 273. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.07.051. ISSN 0090-4295. PMID 35987379. S2CID 251657694. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b Dimitrakoff J, Nickel JC (2022). "Author reply". Urology. 169: 273–274. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.07.049. ISSN 0090-4295. PMID 35985522. S2CID 251658492. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Theoharides TC, Cochrane DE (2004). "Critical role of mast cells in inflammatory diseases and the effect of acute stress". J. Neuroimmunol. 146 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.041. PMID 14698841. S2CID 6866545.

- ^ Theoharides TC, Kalogeromitros D (2006). "The critical role of mast cells in allergy and inflammation". Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1088 (1): 78–99. Bibcode:2006NYASA1088...78T. doi:10.1196/annals.1366.025. PMID 17192558. S2CID 7659928.

- ^ Sant GR, Kempuraj D, Marchand JE, Theoharides TC (2007). "The mast cell in interstitial cystitis: role in pathophysiology and pathogenesis". Urology. 69 (4 Suppl): 34–40. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.383.9862. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1109. PMID 17462477.

- ^ Luu-The V, Bélanger A, Labrie F (April 2008). "Androgen biosynthetic pathways in the human prostate". Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 22 (2): 207–221. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2008.01.008. PMID 18471780.

- ^ "Precision Medicine in Urology: Molecular Mechanisms, Diagnostics and Therapeutic Targets" (PDF). ISSN 2330-1910. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ du Toit T, Swart AC (2020). "The 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione pathway and C11-oxy C21 backdoor pathway are active in benign prostatic hyperplasia yielding 11keto-testosterone and 11keto-progesterone". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 196 105497. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105497. PMID 31626910. S2CID 204734045.

- ^ Lee JC, Muller CH, Rothman I, et al. (February 2003). "Prostate biopsy culture findings of men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome do not differ from those of healthy controls". J. Urol. 169 (2): 584–587, discussion 587–588. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.605.5540. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(05)63958-4. PMID 12544312.

- ^ a b Schaeffer AJ (2003). "Editorial: Emerging concepts in the management of prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". J. Urol. 169 (2): 597–598. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)63961-4. PMID 12544315.

- ^ Theoharides T, Whitmore K, Stanford E, Moldwin R, O'Leary M (December 2008). "Interstitial cystitis: bladder pain and beyond". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 9 (17): 2979–2994. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.7817. doi:10.1517/14656560802519845. PMID 19006474. S2CID 73881007.

- ^ Murphy A, Macejko A, Taylor A, Nadler R (2009). "Chronic prostatitis: management strategies". Drugs. 69 (1): 71–84. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969010-00005. PMID 19192937. S2CID 13127203.

- ^ Dimitrakov J, Dimitrakova E (2009). "Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome – looking back and looking forward". Folia Med (Plovdiv). 51 (3): 42–44. PMID 19957562.

- ^ Rourke W, Khan SA, Ahmed K, Masood S, Dasgupta P, Khan MS (June 2014). "Painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: aetiology, evaluation and management". Arch Ital Urol Androl. 86 (2): 126–131. doi:10.4081/aiua.2014.2.126. PMID 25017594. S2CID 30355982.

- ^ "A New Look at Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain". MAPP Network. Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Habermacher GM, Chason JT, Schaeffer AJ (2006). "Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Annu. Rev. Med. 57: 195–206. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.57.011205.135654. PMID 16409145.

- ^ A Pontari M (December 2002). "Inflammation and anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic prostatitis". Urology. 60 (6 Suppl): 29–33, discussion 33–34. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.383.9485. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02381-6. PMID 12521589.

- ^ Ding XG, Li SW, Zheng XM, Hu LQ (2006). "[IFN-gamma and TGF-beta1, levels in the EPS of patients with chronic abacterial prostatitis]". Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue (in Chinese). 12 (11): 982–984. PMID 17146921.

- ^ Watanabe T, Inoue M, Sasaki K, Araki M, Uehara S, Monden K, et al. (September 2010). "Nerve growth factor level in the prostatic fluid of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is correlated with symptom severity and response to treatment". BJU Int. 108 (2): 248–251. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09716.x. PMID 20883485. S2CID 6979830.

- ^ a b Weidner W, Anderson RU (2007). "Evaluation of acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis and diagnostic management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with special reference to infection/inflammation". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 31 (2): S91 – S95. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.044. PMID 18162376.

- ^ Shoskes DA, Berger R, Elmi A, Landis JR, Propert KJ, Zeitlin S (2008). "Muscle tenderness in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: the chronic prostatitis cohort study". J. Urol. 179 (2): 556–560. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.088. PMC 2664648. PMID 18082223.

- ^ a b Nickel JC, Alexander RB, Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Knauss JS, Propert KJ (2003). "Leukocytes and bacteria in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome compared to asymptomatic controls". J. Urol. 170 (3): 818–822. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000082252.49374.e9. PMID 12913707.

- ^ McNaughton Collins M, Fowler F, Elliott D, Albertsen P, Barry M (March 2000). "Diagnosing and treating chronic prostatitis: do urologists use the four-glass test?". Urology. 55 (3): 403–407. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00536-1. PMID 10699621.

- ^ Leslie A Aaron, et al. (2001). "Comorbid Clinical Conditions in Chronic Fatigue: A Co-Twin Control Study". J Gen Intern Med. 16 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.03419.x. PMC 1495162. PMID 11251747.

- ^ Khadra A, Fletcher P, Luzzi G, Shattock R, Hay P (May 2006). "Interleukin-8 levels in seminal plasma in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and nonspecific urethritis". BJU Int. 97 (5): 1043–1046. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06133.x. PMID 16643489. S2CID 22660010.

- ^ He L, Wang Y, Long Z, Jiang C (December 2009). "Clinical Significance of IL-2, IL-10, and TNF-alpha in Prostatic Secretion of Patients With Chronic Prostatitis". Urology. 75 (3): 654–657. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.061. PMID 19963254.

- ^ Pasqualotto F, Sharma R, Potts J, Nelson D, Thomas A, Agarwal A (June 2000). "Seminal oxidative stress in patients with chronic prostatitis". Urology. 55 (6): 881–885. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00613-5. PMID 10840100.

- ^ Penna G, Mondaini N, Amuchastegui S, Degli Innocenti S, Carini M, Giubilei G, et al. (February 2007). "Seminal plasma cytokines and chemokines in prostate inflammation: interleukin 8 as a predictive biomarker in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and benign prostatic hyperplasia". Eur Urol. 51 (2): 524–533, discussion 533. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.016. hdl:2158/687725. PMID 16905241.

- ^ Chiari R (1983). "Urethral obstruction and prostatitis". Int Urol Nephrol. 15 (3): 245–255. doi:10.1007/BF02083011. PMID 6654631. S2CID 7080545.

- ^ Hruz P, Danuser H, Studer UE, Hochreiter WW (2003). "Non-inflammatory chronic pelvic pain syndrome can be caused by bladder neck hypertrophy". Eur. Urol. 44 (1): 106–110, discussion 110. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00203-3. PMID 12814683.

- ^ Romero Pérez P, Mira Llinares A (1996). "[Complications of the lower urinary tract secondary to urethral stenosis]". Actas Urol Esp (in Spanish). 20 (9): 786–793. PMID 9065088.

- ^ "Prostatitis: Benign Prostate Disease: Merck Manual Professional". Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Treatment of Chronic Prostatitis". Nat Clin Pract Urol. 1 (1). 2004. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ "Multi-disciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Research Network". NIDDK. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ^ Hochreiter W, Bader P (January 2001). "Etiopathogenesis of prostatitis". Urologe A (in German). 40 (1): 4–8. doi:10.1007/s001200050424. PMID 11225430. S2CID 967732.

- ^ Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Dolinga R, Prots D (2009). "Clinical phenotyping of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and correlation with symptom severity". Urology. 73 (3): 538–542, discussion 542–543. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.384.4216. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2008.09.074. PMID 19118880.

- ^ a b Sandhu J, Tu HV (2017). "Recent advances in managing chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". F1000Res. 6: 1747. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10558.1. PMC 5615772. PMID 29034074.

- ^ Doiron RC, Shoskes DA, Nickel JC (June 2019). "Male CP/CPPS: where do we stand?". World J Urol. 37 (6): 1015–1022. doi:10.1007/s00345-019-02718-6. PMID 30864007. S2CID 76662118.

- ^ a b Potts J, Payne RE (May 2007). "Prostatitis: Infection, neuromuscular disorder, or pain syndrome? Proper patient classification is key". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 74 (Suppl 3): 63–71. doi:10.3949/ccjm.74.Suppl_3.S63. PMID 17549825.

- ^ a b c "Diagnosis and Treatment Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome". www.auanet.org. 2014. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ a b Professionals SO. "EAU Guidelines: Chronic Pelvic Pain". Uroweb. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b McNeil DG (30 December 2013). "A Fix for Stress-Related Pelvic Pain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ Champaneria R, Daniels JP, Raza A, Pattison HM, Khan KS (March 2012). "Psychological therapies for chronic pelvic pain: systematic review of randomized controlled trials: Psychological therapies for chronic pelvic pain". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 91 (3): 281–286. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01314.x. PMID 22050516. S2CID 28767715.

- ^ Cheong YC, Smotra G, Williams AC (5 March 2014). "Non-surgical interventions for the management of chronic pelvic pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (3) CD008797. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008797.pub2. PMC 10981791. PMID 24595586.

- ^ Leskinen M, Kilponen A, Lukkarinen O, Tammela T (August 2002). "Transurethral needle ablation for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome (category III prostatitis): a randomized, sham-controlled study". Urology. 60 (2): 300–304. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01704-1. PMID 12137830.

- ^ Hunter CW, Stovall B, Chen G, Carlson J, Levy R (March 2018). "Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Interventional Therapies for Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Review". Pain Physician. 21 (2): 147–167. doi:10.36076/ppj.2018.2.147. ISSN 2150-1149. PMID 29565946.

- ^ Hunter CW, Falowski S (3 February 2021). "Neuromodulation in Treating Pelvic Pain". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 25 (2): 9. doi:10.1007/s11916-020-00927-y. ISSN 1534-3081. PMID 33534006. S2CID 231787453.

- ^ Hunter CW, Yang A (January 2019). "Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation for Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Case Series and Technical Report on a Novel Lead Configuration". Neuromodulation: Journal of the International Neuromodulation Society. 22 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1111/ner.12801. ISSN 1525-1403. PMID 30067887. S2CID 51892311.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Franco JV, Turk T, Jung JH, Xiao YT, Iakhno S, Tirapegui FI, et al. (6 October 2019). Cochrane Urology Group (ed.). "Pharmacological interventions for treating chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (10) CD012552. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012552.pub2. PMC 6778620. PMID 31587256.

- ^ Anothaisintawee T, Attia, J, Nickel, JC, Thammakraisorn, S, Numthavaj, P, McEvoy, M, et al. (5 January 2011). "Management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 305 (1): 78–86. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1913. PMID 21205969.

- ^ Wagenlehner F, Naber K, Bschleipfer T, Brähler E, Weidner W (March 2009). "Prostatitis and male pelvic pain syndrome: diagnosis and treatment". Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 106 (11): 175–183. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0175. PMC 2695374. PMID 19568373.

- ^ Shoskes DA (June 2001). "Use of antibiotics in chronic prostatitis syndromes". Can J Urol. 8 (Suppl 1): 24–28. PMID 11442994.

- ^ Yang G, Wei Q, Li H, Yang Y, Zhang S, Dong Q (2006). "The effect of alpha-adrenergic antagonists in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". J. Androl. 27 (6): 847–852. doi:10.2164/jandrol.106.000661. PMID 16870951.

...treatment duration should be long enough (more than 3 months)

- ^ Cohen JM, Fagin AP, Hariton E, Niska JR, Pierce MW, Kuriyama A, et al. (2012). "Therapeutic Intervention for Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/ CPPS): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 7 (8) e41941. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741941C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041941. PMC 3411608. PMID 22870266.

- ^ Dhar NB, Shoskes DA (2007). "New therapies in chronic prostatitis". Curr Urol Rep. 8 (4): 313–318. doi:10.1007/s11934-007-0078-5. PMID 18519016. S2CID 195365395.

- ^ Capodice JL, Bemis DL, Buttyan R, Kaplan SA, Katz AE (2005). "Complementary and alternative medicine for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2 (4): 495–501. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh128. PMC 1297501. PMID 16322807.

- ^ Curtis Nickel J, Baranowski AP, Pontari M, Berger RE, Tripp DA (2007). "Management of Men Diagnosed With Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome Who Have Failed Traditional Management". Reviews in Urology. 9 (2): 63–72. PMC 1892625. PMID 17592539.

- ^ Larish AM, Dickson RR, Kudgus RA, McGovern RM, Reid JM, Hooten WM, et al. (June 2019). "Vaginal Diazepam for Nonrelaxing Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: The Pharmacokinetic Profile". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 16 (6): 763–766. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.003. ISSN 1743-6109. PMID 31010782. S2CID 128361154.

- ^ Shoskes DA, Thomas KD, Gomez E (2005). "Anti-nanobacterial therapy for men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and prostatic stones: preliminary experience". J. Urol. 173 (2): 474–477. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.384.2090. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000150062.60633.b2. PMID 15643213.

- ^ Rempe S, Hayden JM, Robbins RA, Hoyt JC (30 November 2007). "Tetracyclines and Pulmonary Inflammation". Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets. 7 (4): 232–236. doi:10.2174/187153007782794344. PMID 18220943.

- ^ Urbano P, Urbano F (2007). "Nanobacteria: facts or fancies?". PLOS Pathogens. 3 (5) e55. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030055. PMC 1876495. PMID 17530922.

- ^ Hopkin M (17 April 2008). "Nanobacteria theory takes a hit". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2008.762.

- ^ Martel J, Young JD (8 April 2008). "Purported nanobacteria in human blood as calcium carbonate nanoparticles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (14): 5549–5554. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.5549M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711744105. PMC 2291092. PMID 18385376.

- ^ Leskinen MJ, Vainionp R, Syrjnen S, et al. (2003). "Herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and papillomavirus DNA are not found in patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome undergoing radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer". Urology. 61 (2): 397–401. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02166-0. PMID 12597955.

- ^ Benson PJ, Smith CS (1992). "Cytomegalovirus prostatitis. Case report and review of the literature". Urology. 40 (2): 165–167. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(92)90520-7. PMID 1323895.

- ^ Mastroianni A, Coronado O, Manfredi R, Chiodo F, Scarani P (1996). "Acute cytomegalovirus prostatitis in AIDS". Genitourinary Medicine. 72 (6): 447–448. doi:10.1136/sti.72.6.447. PMC 1195741. PMID 9038649.

- ^ McKay TC, Albala DM, Sendelbach K, Gattuso P (1994). "Cytomegalovirus prostatitis. Case report and review of the literature". International Urology and Nephrology. 26 (5): 535–540. doi:10.1007/bf02767655. PMID 7860201. S2CID 7268832.

- ^ Doble A, Harris JR, Taylor-Robinson D (1991). "Prostatodynia and herpes simplex virus infection". Urology. 38 (3): 247–248. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(91)80355-B. PMID 1653479.

- ^ Leue C, Kruimel J, Vrijens D, Masclee A, van Os J, van Koeveringe G (March 2017). "Functional urological disorders: a sensitized defence response in the bladder-gut-brain axis". Nature Reviews. Urology. 14 (3): 153–163. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2016.227. PMID 27922040. S2CID 2016916.

- ^ Duclos A, Lee C, Shoskes D (August 2007). "Current treatment options in the management of chronic prostatitis". Ther Clin Risk Manag. 3 (4): 507–512. PMC 2374945. PMID 18472971.

- ^ Shoskes D, Katz E (July 2005). "Multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Curr Urol Rep. 6 (4): 296–299. doi:10.1007/s11934-005-0027-0. PMID 15978233. S2CID 195366261.

- ^ Bergman J, Zeitlin S (March 2007). "Prostatitis and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Expert Rev Neurother. 7 (3): 301–307. doi:10.1586/14737175.7.3.301. PMID 17341178. S2CID 24426243.

- ^ Taylor BC, Noorbaloochi S, McNaughton-Collins M, et al. (May 2008). "Excessive antibiotic use in men with prostatitis". Am. J. Med. 121 (5): 444–449. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.043. PMC 2409146. PMID 18456041.

- ^ Daniel Shoskes (2008). Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Humana Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-934115-27-5. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Daniels NA, Link CL, Barry MJ, McKinlay JB (May 2007). "Association between past urinary tract infections and current symptoms suggestive of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". J Natl Med Assoc. 99 (5): 509–516. PMC 2576075. PMID 17534008.

- ^ Nickel J, Tripp D, Chuai S, Litwin M, McNaughton-Collins M, Landis J, et al. (January 2008). "Psychosocial variables affect the quality of life of men diagnosed with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". BJU Int. 101 (1): 59–64. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07196.x. PMID 17924985. S2CID 13568744.

{{cite journal}}:|first15=has generic name (help) - ^ "NIH CPSI". Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (UCPPS) archive. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Marszalek M, Wehrberger C, Temml C, Ponholzer A, Berger I, Madersbacher S (April 2008). "Chronic Pelvic Pain and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Both Sexes: Analysis of 2749 Participants of an Urban Health Screening Project". Eur. Urol. 55 (2): 499–507. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.073. PMID 18395963.

- ^ "Anderson goes". Australian Broadcasting Corporation Transcript. 23 June 2005. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People. Doubleday. 2008. ISBN 978-1-932595-29-1. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ Allison Reitz (July 2009). "John Cleese tour pays the 'Alimony' with West Coast comedy shows". tickenews.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

The star of Monty Python and "A Fish Called Wanda" has been diagnosed with prostatitis, the inflammation of the prostate gland and is undergoing treatment.

Alt URL - ^ Roger Ebert. "The whole truth from Vincent Gallour Flies". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ "Glenn Gould as Patient". Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Dallek R (2003). An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917–1963. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 123. ISBN 978-0-316-17238-7.

- ^ Jeffries S (3 July 2010). "Teach Us to Sit Still: A Sceptic's Search for Health and Healing by Tim Parks". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Astier H. "Prostatitis: 'How I meditated away chronic pelvic pain'". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "The Howard Stern Show for September 4, 2007". Howard Stern. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "The Howard Stern Show for September 5, 2007, Pulling Out a Plum". Howard Stern. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Leavitt D (11 May 2008). "Styron's Choices". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2008.